2.3.2. Managing Energy Balance

Weight Management

The health consequences of too much body fat are numerous, including increased risks for cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes, and some cancers.

With obesity at epidemic proportions in North America it is paramount that policies be implemented or reinforced at all levels of society, and include education, agriculture, industry, urban planning, healthcare, and government.

The following are some main ideas for constructing an environment that promotes health and confronts the obesity epidemic.

At the individual level:

- Purchase fewer prepared foods and eat more whole foods.

- Decrease portion sizes when eating or serving food.

- Eat out less, and when you do eat out choose low-calorie options.

- Walk or bike to work. If this is not feasible, walk while you are at work.

- Take the stairs when you come upon them or better yet, seek them out.

- Walk your neighborhood and know your surroundings. This benefits both health and safety.

- Watch less television.

At the community level:

- Request that your college/workplace provides more access to healthy low-cost foods.

- Support changes in school lunch programs.

- Participate in cleaning up local green spaces and then enjoy them during your leisure time.

- Patronize local farms and fruit-and-vegetable stands.

- Talk to your grocer and ask for better whole-food choices and seafood at a decent price.

- Ask the restaurants you frequently go to, to serve more nutritious food and to accurately display calories of menu items.

At the national level:

- Support policies that increase the walkability of cities.

- Support national campaigns addressing obesity

- Support policies that support local farmers and the increased access and affordability of healthy food.

Balancing Energy Input With Energy Output

To Maintain Weight, Energy Intake Must Balance Energy Output

Recall that the macronutrients you consume are either converted to energy, stored, or used to synthesize macromolecules. A nutrient’s metabolic path is dependent upon energy balance. When you are in a positive energy balance the excess nutrient energy will be stored or used to grow (e.g., during childhood, pregnancy, and wound healing). When you are in negative energy balance you aren’t taking in enough energy to meet your needs, so your body will need to use its stores to provide energy. Energy balance is achieved when intake of energy is equal to energy expended. Weight can be thought of as a whole body estimate of energy balance; body weight is maintained when the body is in energy balance, lost when it is in negative energy balance, and gained when it is in positive energy balance. In general, weight is a good predictor of energy balance, but many other factors play a role in energy intake and energy expenditure. Some of these factors are under your control and others are not. Let us begin with the basics on how to estimate energy intake, energy requirement, and energy output. Then we will consider the other factors that play a role in maintaining energy balance and hence, body weight.

While knowing the number of calories you need each day is useful, it is also pertinent to obtain your calories from nutrient-dense foods and consume the various macronutrients in their Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDRs).

Total Energy Expenditure (Output)

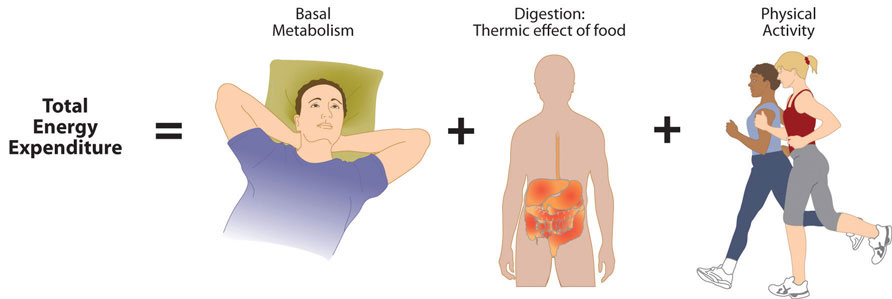

The amount of energy you expend every day includes not only the calories you burn during physical activity, but also the calories you burn while at rest (basal metabolism), and the calories you burn when you digest food. The sum of caloric expenditure is referred to as total energy expenditure (TEE).

Basal metabolism refers to those metabolic pathways necessary to support and maintain the body’s basic functions (e.g. breathing, heartbeat, liver and kidney function) while at rest. The basal metabolic rate (BMR) is the amount of energy required by the body to conduct its basic functions over a certain time period. The great majority of energy expended (50-70%) daily is from conducting life’s basic processes. Of all the organs, the liver requires the most energy (Table 2.3.2.1 “Energy Breakdown of Organs”). Unfortunately, you cannot tell your liver to ramp up its activity level to expend more energy so you can lose weight. BMR is dependent on body size, body composition, sex, age, nutritional status, and genetics. People with a larger frame size have a higher BMR simply because they have more mass. Muscle tissue burns more calories than fat tissue even while at rest and thus the more muscle mass a person has, the higher their BMR. Since females typically have less muscle mass and a smaller frame size than men, their BMRs are generally lower than men’s. As we get older muscle mass declines and thus so does BMR. Nutritional status also affects basal metabolism. Caloric restriction, as occurs while dieting, for example, causes a decline in BMR. This is because the body attempts to maintain homeostasis and will adapt by slowing down its basic functions to offset the decrease in energy intake. Body temperature and thyroid hormone levels are additional determinants of BMR.

| Organ | Percent of energy expended |

| Liver | 27 |

| Brain | 19 |

| Heart | 7 |

| Kidneys | 10 |

| Skeletal muscle (at rest) | 18 |

| Other organs | 19 |

Note: Different organs use different amounts of energy. The liver has the highest energy consumption and the heart has the lowest. Source: FAO/WHO/UNU, 1985. Energy and Protein Requirements. World Health Organization Technical Report Series 724. http://www.fao.org/doCReP/003/aa040e/AA040E00.htm. Updated 1991. Accessed September 17, 2017.

Figure 2.3.2.1 Total Energy Expenditure

The energy required for all the enzymatic reactions that take place during food digestion and absorption of nutrients is called the “thermic effect of food” (TEF) and accounts for about 10% of total energy expended per day.

The other energy required during the day is for physical activity and is referred to as “non-resting energy expenditure” (NREE). Depending on lifestyle, the energy required for this ranges between 15-30% of total energy expended. The main control a person has over TEE is to increase physical activity.

Factors Affecting Energy Intake

Physiology

In the last few decades scientific studies have revealed that how much we eat and what we eat is controlled not only by our own desires, but also is regulated physiologically and influenced by genetics. The hypothalamus in the brain is the main control point of appetite. It receives hormonal and neural signals, which determine if you feel hungry or full. Hunger is an unpleasant sensation of feeling empty that is communicated to the brain by both mechanical and chemical signals from the periphery. Conversely, satiety is the sensation of feeling full and it also is determined by mechanical and chemical signals relayed from the periphery. The hypothalamus contains distinct centers of neural circuits that regulate hunger and satiety.

Hunger pangs are real and so is a “growling” stomach. When the stomach is empty it contracts, producing the characteristic pang and “growl.” The stomach’s mechanical movements relay neural signals to the hypothalamus, which relays other neural signals to parts of the brain. This results in the conscious feeling of the need to eat. Alternatively, after you eat a meal the stomach stretches and sends a neural signal to the brain stimulating the sensation of satiety and relaying the message to stop eating. The stomach also sends out certain hormones when it is full and others when it is empty. These hormones communicate to the hypothalamus and other areas of the brain either to stop eating or to find some food.

Fat tissue also plays a role in regulating food intake. Fat tissue produces the hormone leptin, which communicates to the satiety center in the hypothalamus that the body is in positive energy balance. The discovery of leptin’s functions sparked a craze in the research world and the diet pill industry, as it was hypothesized that if you give leptin to a person who is overweight, they will decrease their food intake. Alas, this is not the case. In several clinical trials it was found that people who are overweight or obese are actually resistant to the hormone, meaning their brain does not respond as well to it. [1] Therefore, when you administer leptin to an overweight or obese person there is no sustained effect on food intake.

Nutrients themselves also play a role in influencing food intake. The hypothalamus senses nutrient levels in the blood. When they are low the hunger center is stimulated, and when they are high the satiety center is stimulated. Furthermore, cravings for salty and sweet foods have an underlying physiological basis. Both undernutrition and overnutrition affect hormone levels and the neural circuitry controlling appetite, which makes losing or gaining weight a substantial physiological hurdle.

Furthermore, there is extensive evidence showing that the body’s physiological systems fight weight loss to favour weight gain. From an evolutionary standpoint this makes sense, as in times of famine, weight loss would be life threatening. Therefore the body has adapted to prevent weight loss. The set-point-theory states that each individual has a set weight that their body has become accustomed to living at. Any threat to decrease this weight will result in the body to adapt its functions to reduce energy expenditure. Unfortunately, this adaptation does not work in the other direction and our body openly accepts excess calories and resulting weight gain. This effect is called adaptive thermogenesis and is defined as the greater than predicted reduction in energy expenditure following weight loss. Adaptive thermogenesis is part of the reason why it is so hard for the majority of individuals to maintain any weight loss that they have achieved.

Genetic Influences

Genetics certainly play a role in body fatness and weight and also affects food intake. Children who have been adopted typically are similar in weight and body fatness to their biological parents. Moreover, identical twins are twice as likely to be of similar weights as compared to fraternal twins. The scientific search for obesity genes is ongoing and a few have been identified, such as the gene that encodes for leptin. However, overweight and obesity that manifests in millions of people is not likely to be attributed to one or even a few genes, but the interactions of hundreds of genes with the environment. In fact, when an individual has a mutated version of the gene coding for leptin, they are obese, but only a few dozen people around the world have been identified as having a completely defective leptin gene. Even though genetics can influence weight, having an “obesity gene” does not destine you to be overweight. Obesity genes simply increase you risk of developing obesity. With proper nutrition and physical activity a health weight can still be maintained.

Psychological/Behavioural Influences

When your mouth waters in response to the smell of a roasting Thanksgiving turkey and steaming hot pies, you are experiencing a psychological influence on food intake. A person’s perception of good-smelling and good-tasting food influences what they eat and how much they eat. Mood and emotions are associated with food intake. Depression, low self-esteem, compulsive disorders, and emotional trauma are sometimes linked with increased food intake and obesity.

Certain behaviours can be predictive of how much a person eats. Some of these are how much food a person heaps onto their plate, how often they snack on calorie-dense, salty foods, how often they watch television or sit at a computer, and how often they eat out. A study published in a 2008 issue of Obesity looked at characteristics of Chinese buffet patrons. The study found that those who chose to immediately eat before browsing the buffet used larger plates, used a fork rather than chopsticks, chewed less per bite of food, and had higher BMIs than patrons who did not exhibit these behaviours.[2]

Of course many behaviours are reflective of what we have easy access to—a concept we will discuss next.

Societal Influences

It is without a doubt that the North American society affects what and how much we eat. Portion sizes have increased dramatically in the past few decades.

To generalize, most fast food items have little nutritional merit as they are highly processed and rich in saturated fat, salt, and added sugars. The fast food business is likely to continue to grow in North America (and the rest of the world) and greatly affect the diets of whole populations. Because it is unrealistic to say that North Americans should abruptly quit eating fast food to save their health (because they will not) society needs to come up with ideas that push nutrient-dense whole foods into the fast food industry. You may have observed that this largely consumer-driven push is having some effect on the foods the fast food industry serves (just watch a recent Subway commercial, or check the options now available in a McDonald’s Happy Meal). Pushing the fast food industry to serve healthier foods is a realistic and positive way to improve the American diet.

Currently we are living in the most complex food system of all time. Never have there been so many advertisements to navigate and choices to be made. Knowing what is truly healthy for us and what is not is nearly impossible. Certainly education is a large part of making the right choices. However a general rule is to look for the foods that have the least advertising ie. an apple compared to an apple juice. You will never see an advertisement for an apple because there is a lack of industry behind it. However, the apple juice which has been processed and likely loaded with excess sugar comes from a company looking to make money, therefore there will be health claims and other advertising tricks to get you to buy it. Often it is the quietest foods that are the healthiest for us. Additionally be critical of advertising claims such as “cholesterol free” or “GMO free”. These are purposefully placed to entice you to buy this product over others. Sometime foods would have never even contained cholesterol or GMOs to start with.

Support the consumer movement of pushing the fast food industry and your favorite local restaurants into serving more nutrient-dense foods. You can begin this task by starting simple, such as requesting extra tomatoes and lettuce on your burger and more nutrient-dense choices in the salad bar. Also, choose their low-calorie menu options and help support the emerging market of healthier choices in the fast food industry. In today’s fast-paced society, it is difficult for most people to avoid fast food all the time. When you do need a quick bite on the run, choose the fast food restaurants that serve healthier foods. Also, start asking for caloric contents of foods so that the restaurant becomes more aware that their patrons are being calorie conscious.

Factors Affecting Energy Expenditure

Physiological and Genetic Influences

Why is it so difficult for some people to lose weight and for others to gain weight? One theory is that every person has a “set point” of energy balance. This set point can also be called a fat-stat or lipostat, meaning the brain senses body fatness and triggers changes in energy intake or expenditure to maintain body fatness within a target range. Some believe that this theory provides an explanation as to why after dieting, most people return to their original weight not long after stopping the diet. Another theory is referred to as the “settling” point system, which takes into account (more so than the “set-point” theory) the contribution of an obesity-promoting environment to weight gain. In this model, the reservoir of body fatness responds to energy intake or energy expenditure, such that if a person is exposed to a greater amount of food, body fatness increases, or if a person watches more television body fatness increases. A major problem with these theories is that they overgeneralize and do not take into account that not all individuals respond in the same way to changes in food intake or energy expenditure. This brings up the importance of the interactions of genes and the environment.

Not all individuals who take a weight-loss drug lose weight and not all people who smoke are thin. An explanation for these discrepancies is that each individual’s genes respond differently to a specific environment. Alternatively, environmental factors can influence a person’s gene profile, which is exemplified by the effects of the prenatal environment on body weight and fatness and disease incidence later in life.[3]

One example is a study of the offspring of women who were overweight during pregnancy had a greater propensity for being overweight and for developing Type 2 diabetes. Thus, undernutrition and overnutrition during pregnancy influence body weight and disease risk for offspring later in life. They do so by adapting energy metabolism to the early nutrient and hormonal environment in the womb.

Psychological/Behavioural Influence

Sedentary behaviour is defined as the participation in the pursuits in which energy expenditure is no more than one-and-one-half times the amount of energy expended while at rest and include sitting, reclining, or lying down while awake. Of course, the sedentary lifestyle of many North Americans contributes to their average energy expenditure in daily life. Simply put, the more you sit, the less energy you expend. A study published in a 2008 issue of the American Journal of Epidemiology reports that 55 percent of Americans spend 7.7 hours in sedentary behaviour daily.[4]

Fortunately, including only a small amount of low-level physical activity benefits weight control. A study published in the June 2001 issue of the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity reports that even breaking up sitting-time with frequent but brief increased energy expenditure activities, such as walking for five minutes every hour, helps maintain weight and even aids in weight loss.[5]

North Americans partake in an excessive amount of screen time, which is a sedentary behaviour that not only reduces energy expenditure, but also contributes to weight gain because of the exposure to aggressive advertising campaigns for unhealthy foods.

Societal Influence

Many societal factors influence the number of calories burned in a day. Escalators, moving walkways, and elevators (not to mention cars!) are common modes of transportation that reduce average daily energy expenditure. Office work, high-stress jobs, and occupations requiring extended working hours are all societal pressures that reduce the time allotted for exercise. Even the remote controls that many have for various electronic devices in their homes contribute to society being less active.

Socioeconomic status has been found to be inversely proportional to weight gain. One reason for this relationship is that inhabitants of low-income neighborhoods have reduced access to safe streets and parks for walking. Another is that fitness clubs are expensive and few are found in lower-income neighborhoods.

Chronic Diseases

Chronic diseases are ongoing, life-threatening, and life-altering health challenges. They are the leading cause of death worldwide and are increasing in frequency. They cause significant physical and emotional suffering and are an impediment to economic growth and vitality. It is important, now more than ever, to understand the different risk factors for chronic disease and to learn how to prevent their development.

The Risk Factors of Chronic Disease

A risk factor is an indicator that your chances for acquiring a chronic disease may be increased. However having or being exposed to a risk factors does not 100% guarantee that the disease will develop. Risk factors therefore correlate to disease development but cannot be said with 100% certainty that they are the sole causation. For example, if a person gets sick with the flu, we can say with certainty that the illness was caused by a virus. Whereas, even though the risk factor of a sedentary lifestyle is highly correlated to the development of cardiovascular disease, we cannot say that this risk factor caused cardiovascular disease because there are several other factors that may have contributed to the development of this disease.

Chronic disease usually develops alongside a combination of the following risk factors:

- genetics

- age

- a prior disease such as obesity or hypertension

- dietary and lifestyle choices

- environmental problems

Risk factors such as genetics and age cannot be changed. However, some risk factors can be altered to promote health and wellness, such as diet. For example, a person who continuously eats a diet high in sugars, saturated fats, and red meat is at risk for becoming obese and developing Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or several other conditions. Making more healthy dietary choices can greatly reduce that risk. Being a woman over age sixty-five is a risk factor for developing osteoporosis, but that cannot be changed. Also, people without a genetic predisposition for a particular chronic illness can still develop it. Not having a genetic predisposition for a chronic disease is not a guarantee of immunity.

Identifying Your Risk Factors

To estimate your own risk factors for developing certain chronic diseases, search through your family’s medical history. What diseases do you note showing up among close blood relatives? At your next physical, pay attention to your blood tests and ask the doctor if any results are out of normal range. It is also helpful to note your vital signs, particularly your blood pressure and resting heart rate. In addition, you may wish to keep a food diary to make a note of the dietary choices that you make on a regular basis and be aware of foods that are high in saturated fat, among other unhealthy options. As a general rule, it is important to look for risk factors that you can modify to promote your health. For example, if you discover that your grandmother, aunt, and uncle all suffered from high blood pressure, then you may decide to avoid a high sodium diet. Identifying your risk factors can arm you with the information you need to help ward off disease.

Health Risks of Being Overweight and Being Obese

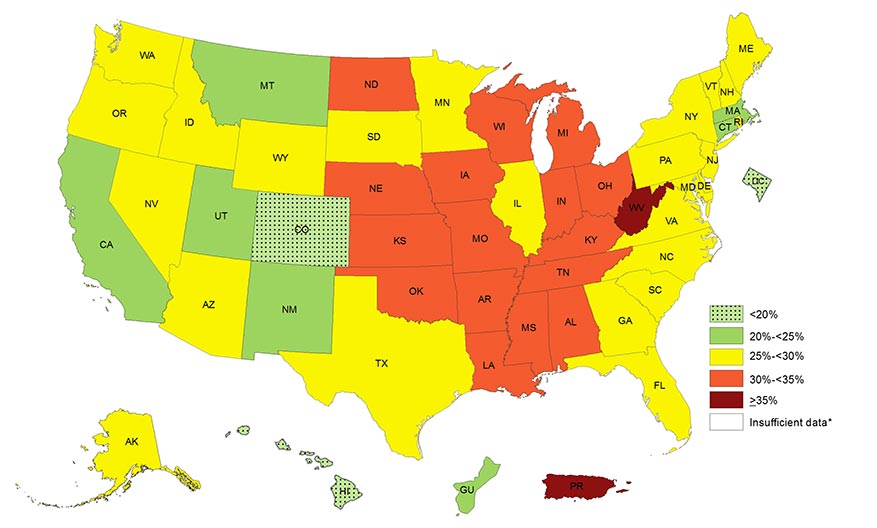

State Map of the Prevalence of Obesity in America

Visit https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html to see the prevalence of self-reported obesity among U.S. adults from 2014-2016. Source: Weight Management

As BMIs increase over 25, health risk increases for heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, hypertension, endometrial cancer, postmenopausal breast cancer, colon cancer, stroke, osteoarthritis, liver disease, gallbladder disorders, and hormonal disorders. The WHO reports that overweight and obesity are the fifth leading cause for deaths globally, and estimates that more than 2.8 million adults die annually as a result of being overweight or obese.[6] Moreover, overweight and obesity contribute to 44% of the Type 2 diabetes burden, 23% of the heart disease burden, and between 7 and 41% of the burden of certain cancers.[7]

Similar to other public health organizations, the WHO states the main causes of the obesity epidemic worldwide are the increased intake of energy-dense food and decreased level of physical activity that is mainly associated with modernization, industrialization, and urbanization. The environmental changes that contribute to the dietary and physical activity patterns of the world today are associated with the lack of policies that address the obesity epidemicin the food and health industry, urban planning, agriculture, and education sectors.

The Crisis of Obesity

Excessive weight gain has become an epidemic. According to Health Canada, between 2007 and 2017, 34% of Canadians were overweight and 27% of Canadians were had obesity. [8] Obesity in particular puts people at risk for a host of complications, including Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, high cholesterol, hypertension, osteoarthritis, and some forms of cancer. The more overweight a person is, the greater his or her risk of developing life-threatening complications. There is no single cause of obesity and no single way to treat it. However, a healthy, nutritious diet is generally the first step, including consuming more fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and lean meats and dairy products and less processed high sugar and fat foods.[9]

Diabetes

What Is Diabetes?

Diabetes is one of the top three diseases in North America. It affects millions of people and causes tens of thousands of deaths each year. Diabetes is a metabolic disease of insulin deficiency and glucose over-sufficiency. Like other diseases, genetics, nutrition, environment, and lifestyle are all involved in determining a person’s risk for developing diabetes. One sure way to decrease your chances of getting diabetes is to maintain an optimal body weight by adhering to a diet that is balanced in carbohydrate, fat, and protein intake. There are three different types of diabetes: Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes, and gestational diabetes.

Type 1 Diabetes

Type 1 diabetes is a metabolic disease in which insulin-secreting cells in the pancreas are killed by an abnormal response of the immune system, causing a lack of insulin in the body. Its onset typically occurs before the age of thirty. The only way to prevent the deadly symptoms of this disease is to inject insulin under the skin.

A person with Type 1 diabetes usually has a rapid onset of symptoms that include hunger, excessive thirst and urination, and rapid weight loss. Because the main function of glucose is to provide energy for the body, when insulin is no longer present there is no message sent to cells to take up glucose from the blood. Instead, cells use fat and proteins to make energy, resulting in weight loss. If Type 1 diabetes goes untreated individuals with the disease will develop a life-threatening condition called ketoacidosis. This condition occurs when the body uses fats and not glucose to make energy, resulting in a build-up of ketone bodies in the blood. It is a severe form of ketosis with symptoms of vomiting, dehydration, rapid breathing, and confusion and eventually coma and death. Upon insulin injection these severe symptoms are treated and death is avoided. Unfortunately, while insulin injection prevents death, it is not considered a cure. People who have this disease must adhere to a strict diet to prevent the development of serious complications. Type 1 diabetics are advised to consume a diet low in the types of carbohydrates that rapidly spike glucose levels (high-Glucose Index (GI) foods), to count the carbohydrates they eat, to consume healthy-carbohydrate foods, and to eat small meals frequently. These guidelines are aimed at preventing large fluctuations in blood glucose. Frequent exercise also helps manage blood-glucose levels. Type 1 diabetes accounts for between 5 and 10 percent of diabetes cases.

Type 2 Diabetes

The other 90 to 95 percent of diabetes cases are Type 2 diabetes. Type 2 diabetes is defined as a metabolic disease of insulin insufficiency, but it is also caused by muscle, liver, and fat cells no longer responding to the insulin in the body (Figure 2.3.2.2 “Healthy Individuals and Type 2 Diabetes”). In brief, cells in the body have become resistant to insulin and no longer receive the full physiological message of insulin to take up glucose from the blood. Thus, similar to patients with Type 1 diabetes, those with Type 2 diabetes also have high blood-glucose levels.

Figure 2.3.2.2 Healthy Individuals and Type 2 Diabetes

For Type 2 diabetics, the onset of symptoms is more gradual and less noticeable than for Type 1 diabetics:

- The first stage of Type 2 diabetes is characterized by high glucose and insulin levels. This is because the insulin-secreting cells in the pancreas attempt to compensate for insulin resistance by making more insulin.

- In the second stage of Type 2 diabetes, the insulin-secreting cells in the pancreas become exhausted and die. At this point, Type 2 diabetics also have to be treated with insulin injections.

The goal of healthcare providers is to prevent the second stage from happening. As with Type 1 diabetes, chronically high-glucose levels cause big detriments to health over time, so another goal for patients with Type 2 diabetes is to properly manage their blood-glucose levels. The front-line approach for treating Type 2 diabetes includes eating a healthy diet and increasing physical activity.

According to the most recent data, about 3.0 million Canadians (8.1%) were living with diagnosed diabetes in 2013–2014, representing 1 in 300 children and youth (1–19 years), and 1 in 10 adults (20 years and older).[10]

The Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) estimates that as of 2010, 25.8 million Americans have diabetes, which is 8.3 percent of the population.[11] In 2007 the cost of diabetes to the United States was estimated at $174 billion.[12] The incidence of Type 2 diabetes has more than doubled in America in the past thirty years and the rise is partly attributed to the increase in obesity in this country.

Genetics, environment, nutrition, and lifestyle all play a role in determining a person’s risk for Type 2 diabetes. We have the power to change some of the determinants of disease but not others. The Diabetes Prevention Trial that studied lifestyle and drug interventions in more than three thousand participants who were at high risk for Type 2 diabetes found that intensive lifestyle intervention reduced the chances of getting Type 2 diabetes by 58 percent.[13]

Gestational Diabetes

During pregnancy some women develop gestational diabetes. Gestational diabetes is characterized by high blood-glucose levels and insulin resistance. The exact cause is not known but does involve the effects of pregnancy hormones on how cells respond to insulin. Gestational diabetes can cause pregnancy complications and it is common practice for healthcare practitioners to screen pregnant women for this metabolic disorder. The disorder normally ceases when the pregnancy is over, but the National Diabetes Information Clearing House notes that women who had gestational diabetes have between a 40 and 60 percent likelihood of developing Type 2 diabetes within the next ten years.[14] Gestational diabetes not only affects the health of a pregnant woman but also is associated with an increased risk of obesity and Type 2 diabetes in her child.

Prediabetes

As the term infers, prediabetes is a metabolic condition in which people have moderately high glucose levels, but do not meet the criteria for diagnosis as a diabetic. Over seventy-nine million Americans are prediabetic and at increased risk for Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.[15] The National Diabetes Information Clearing House reports that 35 percent of adults aged twenty and older, and 50 percent of those over the age of sixty-five have prediabetes.[16]

Long-Term Health Consequences of Diabetes

The long-term health consequences of diabetes are severe. They are the result of chronically high glucose concentrations in the blood accompanied by other metabolic abnormalities such as high blood-lipid levels. People with diabetes are between two and four times more likely to die from cardiovascular disease. Diabetes is the number one cause of new cases of blindness, lower-limb amputations, and kidney failure. Many people with diabetes develop peripheral neuropathy, characterized by muscle weakness, loss of feeling and pain in the lower extremities. More recently, there is scientific evidence to suggest people with diabetes are also at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Diabetes Treatment

Keeping blood-glucose levels in the target range (70–130 mg/dL before a meal) requires careful monitoring of blood-glucose levels with a blood-glucose meter, strict adherence to a healthy diet, and increased physical activity. Type 1 diabetics begin insulin injections as soon as they are diagnosed. Type 2 diabetics may require oral medications and insulin injections to maintain blood-glucose levels in the target range. The symptoms of high blood glucose, also called hyperglycemia, are difficult to recognize, diminish in the course of diabetes, and are mostly not apparent until levels become very high. The symptoms are increased thirst and frequent urination. Having too low blood glucose levels, known as hypoglycemia, is also detrimental to health. Hypoglycemia is more common in Type 1 diabetics and is most often caused by injecting too much insulin or injecting it at the wrong time. The symptoms of hypoglycemia are more acute including shakiness, sweating, nausea, hunger, clamminess, fatigue, confusion, irritability, stupor, seizures, and coma. Hypoglycemia can be rapidly and simply treated by eating foods containing about ten to twenty grams of fast-releasing carbohydrates. If symptoms are severe a person is either treated by emergency care providers with an intravenous solution of glucose or given an injection of glucagon, which mobilizes glucose from glycogen in the liver. Some people who are not diabetic may experience reactive hypoglycemia. This is a condition in which people are sensitive to the intake of sugars, refined starches, and high glucose index foods. Individuals with reactive hypoglycemia have some symptoms of hypoglycemia. Symptoms are caused by a higher than normal increase in blood-insulin levels. This rapidly decreases blood-glucose levels to a level below what is required for proper brain function.

The major determinants of Type 2 diabetes that can be changed are overnutrition and a sedentary lifestyle. Therefore, reversing or improving these factors by lifestyle interventions markedly improve the overall health of Type 2 diabetics and lower blood-glucose levels. In fact it has been shown that when people are overweight, losing as little as 5% of total body weight (10lb for a 200lb person) decreases blood-glucose levels in Type 2 diabetics. Furthermore, the Diabetes Prevention Trial demonstrated that when individuals at risk for Type 2 diabetes first adhered to a diet containing between 1,200-1,800 kcal/day with a dietary fat intake of <25% and second increase physical activity to at least 150 min/week they achieved an average weight loss of 7% and significantly decreased their chances of developing Type 2 diabetes.[17]

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) has a website that provides information and tips for helping diabetics answer the question, “What Can I Eat”. In regard to carbohydrates the ADA recommends diabetics keep track of the carbohydrates they eat and set a limit. These dietary practices will help keep blood-glucose levels in the target range.

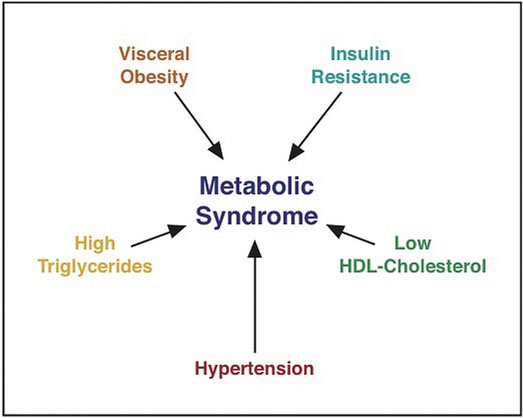

Figure 2.3.2.3 Metabolic Syndrome

Source: Weight Management

A Combination of Risk Factors Increases the Chances for Chronic Disease

Having more than one risk factor for Type 2 diabetes substantially increases a person’s chances for developing the disease. Metabolic syndrome refers to a medical condition in which people have three or more risk factors for Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) people are diagnosed with this syndrome if they have central (abdominal) obesity and any two of the following health parameters: triglycerides greater than 150 mg/dL; high density lipoproteins (HDL) lower than 40 mg/dL; systolic blood pressure above 130mmHg, or diastolic above 85 mmHg; fasting blood-glucose levels greater than 100 mg/dL.[18] The IDF estimates that between 20 and 25 percent of adults worldwide have metabolic syndrome. Studies vary, but people with metabolic syndrome have between a 9 and 30 times greater chance for developing Type 2 diabetes than those who do not have the syndrome.[19]

Disease Prevention and Management

Eating fresh, healthy foods not only stimulates your taste buds, but also can improve your quality of life and help you to live longer. As discussed, food fuels your body and helps you to maintain a healthy weight. Nutrition also contributes to longevity and plays an important role in preventing a number of diseases and disorders, from obesity to cardiovascular disease. Some dietary changes can also help to manage certain chronic conditions, including high blood pressure and diabetes. A doctor or a nutritionist can provide guidance to determine the dietary changes needed to ensure and maintain your health.

- Dardeno TA, Chou, SH, et al. Leptin in Human Physiology and Therapeutics. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2010; 31(3), 377–93. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2916735/?tool=pubmed. Accessed September 22, 2017. ↵

- Levin BE. Developmental Gene X Environment Interactions Affecting Systems Regulating Energy Homeostasis and Obesity. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2010; 3, 270–83. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2903638/?tool=pubmed. Accessed September 22, 2017. ↵

- Matthews CE, Chen KY, et al. Amount of Time Spent in Sedentary Behaviors in the United States, 2003–2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2008; 167(7), 875–81. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18303006. Accessed September 22, 2017. ↵

- Matthews CE, Chen KY, et al. Amount of Time Spent in Sedentary Behaviors in the United States, 2003–2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2008; 167(7), 875–81. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18303006. Accessed September 22, 2017. ↵

- Wu Y. Overweight and Obesity in China. Br Med J. 2006; 333(7564), 362-363. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1550451/. Accessed September 22, 2017. ↵

- Obesity and Overweight. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/. Updated June 2016. Accessed September 22, 2017. ↵

- Obesity and Overweight. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/. Updated June 2016. Accessed September 22, 2017. ↵

- https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2018033-eng.htm ↵

- Overweight and Obesity Statistics.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/overweight-obesity. Accessed April 15, 2018. ↵

- Nov 14, 2017. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/diabetes-canada-highlights-chronic-disease-surveillance-system.html Nov 14, 2017.https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/diabetes-canada-highlights-chronic-disease-surveillance-system.html ↵

- Diabetes Research and Statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/index.html. Updated March 14, 2018. Accessed April 15, 2018. ↵

- Diabetes Quick Facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/quick-facts.html. Updated July 24, 2017. Accessed April 15, 2018. ↵

- Knowler WC. Reduction in the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes with Lifestyle Intervention or Metformin. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002; 346(6), 393–403. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa012512. Accessed April 15, 2018. ↵

- Diabetes Overview. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview. Accessed April 15, 2018. ↵

- Diabetes Overview. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview. Accessed April 15, 2018. ↵

- Diabetes Overview. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview. Accessed April 15, 2018. ↵

- Knowler WC. Reduction in the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes with Lifestyle Intervention or Metformin. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002; 346(6), 393–403. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa012512. Accessed April 15, 2018. ↵

- The IDF Consensus Worldwide Definition of the Metabolic Syndrome. International Diabetes Federation.https://www.idf.org/our-activities/advocacy-awareness/resources-and-tools/60:idfconsensus-worldwide-definitionof-the-metabolic-syndrome.html. Accessed April 15, 2018. ↵

- The IDF Consensus Worldwide Definition of the Metabolic Syndrome. International Diabetes Federation.https://www.idf.org/our-activities/advocacy-awareness/resources-and-tools/60:idfconsensus-worldwide-definitionof-the-metabolic-syndrome.html. Accessed April 15, 2018. ↵ ↵