5.2: Sports

Middle childhood seems to be a great time to introduce children to organized sports, and in fact, many parents do. Nearly 3 million children play soccer in the United States (United States Youth Soccer, 2012). This activity promises to help children build social skills, improve athletically and learn a sense of competition. However, it has been suggested that the emphasis on competition and athletic skill can be counterproductive and lead children to grow tired of the game and want to quit. In many respects, it appears that children’s activities are no longer children’s activities once adults become involved and approach the games as adults rather than children. The U. S. Soccer Federation recently advised coaches to reduce the amount of drilling engaged in during practice and to allow children to play more freely and to choose their own positions. The hope is that this will build on their love of the game and foster their natural talents.

Sports are important for children. Children’s participation in sports has been linked to:

- Higher levels of satisfaction with family and overall quality of life in children

- Improved physical and emotional development

- Better academic performance

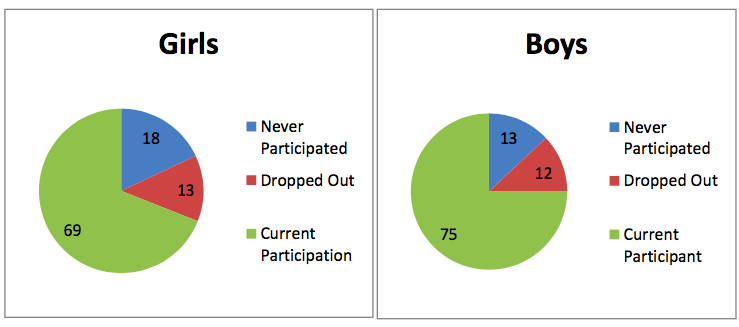

Yet, a study on children’s sports in the United States (Sabo & Veliz, 2008) has found that gender, poverty, location, ethnicity, and disability can limit opportunities to engage in sports. Girls were more likely to have never participated in any type of sport (see Figure 5.2).

Total girls (n=1051). Total boys (n=1081). T-test comparing gender and students who have never partcipated in sports. t=-3.038**, p=.002, df=2130

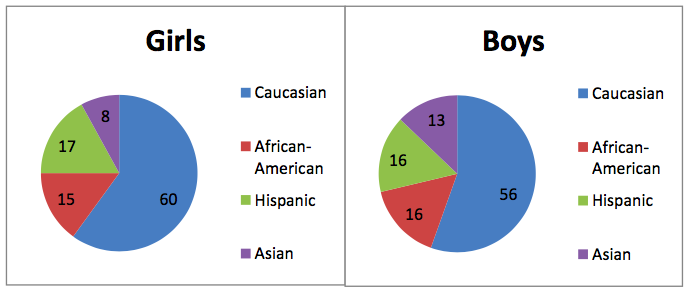

They also found that fathers may not be providing their daughters as much support as they do their sons. While boys rated their fathers as their biggest mentor who taught them the most about sports, girls rated coaches and physical education teachers as their key mentors. Sabo and Veliz also found that children in suburban neighborhoods had a much higher participation of sports than boys and girls living in rural or urban centers. In addition, Caucasian girls and boys participated in organized sports at higher rates than minority children (see Figure 5.3).

Girls – Caucasian (n=425); African-American (n=106); Hispanic (n=124); Asian (n=55)

Boys – Caucasian (n=435); African-American (n=127); Hispanic (n=123); Asian (n=99)

Finally, Sabo and Veliz asked children who had dropped out of organized sports why they left. For both girls and boys, the number one answer was that it was no longer any fun (see Table 5.1). According to the Sport Policy and Research Collaborative (SPARC) (2013), almost 1 in 3 children drop out of organized sports, and while there are many factors involved in the decisions to drop out, one suggestion has been the lack of training that coaches of children’s sports receive may be contributing to this attrition (Barnett, Smoll & Smith, 1992). Several studies have found that when coaches receive proper training the drop-out rate is about 5% instead of the usual 30% (Fraser-Thomas, Côté, & Deakin, 2005; SPARC, 2013).

| Girls | Boys | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| I was not having fun | 38% | I was not having fun | 39% |

| I wanted to focus more on studying and grades | 36% | I had a health problem or injury | 29% |

| I had a health problem or injury | 27% | I wanted to focus more on studying and grades | 26% |

| I wanted to focus more on other clubs or activities | 22% | I did not like or get along with the coach | 22% |

| I did not like or get along with the coach | 18% | I wanted to focus more on other clubs or activities | 18% |

| I did not like or get along with others on the team | 16% | I did not like or get along with others on the team | 16% |

| I was not a good enough player | 15% | I was not a good enough player | 15% |

| My family worried about me getting hurt or injured while playing sports | 14% | My family worried about me getting hurt or injured while playing sports | 12% |

Welcome to the world of e-sports: The recent SPARC (2016) report on the “State of Play” in the United States highlights a disturbing trend. One in four children between the ages of 5 and 16 rate playing computer games with their friends as a form of exercise. In addition, e-sports, which as SPARC writes is about as much a sport as poker, involves children watching other children play video games. Over half of males, and about 20% of females, aged 12-19, say they are fans of e-sports.

Since 2008 there has also been a downward trend in the number of sports children are engaged in, despite a body of research evidence that suggests that specializing in only one activity can increase the chances of injury, while playing multiple sports is protective (SPARC, 2016). A University of Wisconsin study found that 49% of athletes who specialized in a sport experienced an injury compared with 23% of those who played multiple sports (McGuine, 2016).

Physical Education: For many children, physical education in school is a key component in introducing children to sports. After years of schools cutting back on physical education programs, there has been a turn around, prompted by concerns over childhood obesity and the related health issues. Despite these changes, currently only the state of Oregon and the District of Columbia meet PE guidelines of a minimum of 150 minutes per week of physical activity in elementary school and 225 minutes in middle school (SPARC, 2016).