4.20: Parenting Styles

Relationships between parents and children continue to play a significant role in children’s development during early childhood. As children mature, parent-child relationships naturally change. Preschool and grade-school children are more capable, have their own preferences, and sometimes refuse or seek to compromise with parental expectations. This can lead to greater parent-child conflict, and how conflict is managed by parents further shapes the quality of parent-child relationships.

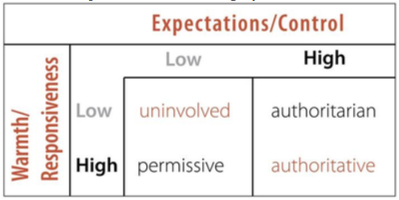

Baumrind (1971) identified a model of parenting that focuses on the level of control/ expectations that parents have regarding their children and how warm/responsive they are. This model resulted in four parenting styles. In general, children develop greater competence and self-confidence when parents have high, but reasonable expectations for children’s behavior, communicate well with them, are warm, loving and responsive, and use reasoning, rather than coercion as preferred responses to children’s misbehavior. This kind of parenting style has been described as Authoritative (Baumrind, 2013). Authoritative parents are supportive and show interest in their kids’ activities, but are not overbearing and allow them to make constructive mistakes. Parents allow negotiation where appropriate, and consequently this type of parenting is considered more democratic.

Authoritarian is the traditional model of parenting in which parents make the rules and children are expected to be obedient. Baumrind suggests that authoritarian parents tend to place maturity demands on their children that are unreasonably high and tend to be aloof and

distant. Consequently, children reared in this way may fear rather than respect their parents and, because their parents do not allow discussion, may take out their frustrations on safer targets- perhaps as bullies toward peers.

Permissive parenting involves holding expectations of children that are below what could be reasonably expected from them. Children are allowed to make their own rules and determine their own activities. Parents are warm and communicative, but provide little structure for their children. Children fail to learn self-discipline and may feel somewhat insecure because they do not know the limits.

Uninvolved parents are disengaged from their children. They do not make demands on their children and are non-responsive. These children can suffer in school and in their relationships with their peers (Gecas & Self, 1991).

Keep in mind that most parents do not follow any model completely. Real people tend to fall somewhere in between these styles. Sometimes parenting styles change from one child to the next or in times when the parent has more or less time and energy for parenting. Parenting styles can also be affected by concerns the parent has in other areas of his or her life. For example, parenting styles tend to become more authoritarian when parents are tired and perhaps more authoritative when they are more energetic. Sometimes parents seem to change their parenting approach when others are around, maybe because they become more self-conscious as parents or are concerned with giving others the impression that they are a “tough” parent or an “easygoing” parent. Additionally, parenting styles may reflect the type of parenting someone saw modeled while growing up. See Table 4.3 for Baumrind’s parenting style descriptions.

Culture: The impact of culture and class cannot be ignored when examining parenting styles. The model of parenting described above assumes that the authoritative style is the best because this style is designed to help the parent raise a child who is independent, self-reliant and responsible. These are qualities favored in “individualistic” cultures such as the United States, particularly by the middle class. However, in “collectivistic” cultures such as China or Korea, being obedient and compliant are favored behaviors. Authoritarian parenting has been used historically and reflects cultural need for children to do as they are told. African-American, Hispanic and Asian parents tend to be more authoritarian than non-Hispanic whites. In societies where family members’ cooperation is necessary for survival, rearing children who are independent and who strive to be on their own makes no sense. But in an economy based on being mobile in order to find jobs and where one’s earnings are based on education, raising a child to be independent is very important.

In a classic study on social class and parenting styles Kohn (1977) explains that parents tend to emphasize qualities that are needed for their own survival when parenting their children. Working class parents are rewarded for being obedient, reliable, and honest in their jobs. They are not paid to be independent or to question the management; rather, they move up and are considered good employees if they show up on time, do their work as they are told, and can be counted on by their employers. Consequently, these parents reward honesty and obedience in their children. Middle class parents who work as professionals are rewarded for taking initiative, being self-directed, and assertive in their jobs. They are required to get the job done without being told exactly what to do. They are asked to be innovative and to work independently. These parents encourage their children to have those qualities as well by rewarding independence and self-reliance. Parenting styles can reflect many elements of culture.

Spanking

Spanking is often thought of as a rite of passage for children, and this method of discipline continues to be endorsed by the majority of parents (Smith, 2012). Just how effective is spanking, however, and are there any negative consequences? After reviewing the research, Smith (2012) states “many studies have shown that physical punishment, including spanking, hitting and other means of causing pain, can lead to increased aggression, antisocial behavior, physical injury and mental health problems for children” (p. 60). Gershoff, (2008) reviewed decades of research and recommended that parents and caregivers make every effort to avoid physical punishment and called for the banning of physical discipline in all U.S. schools.

In a longitudinal study that followed more than 1500 families from 20 U.S. cities, parents’ reports of spanking were assessed at ages three and five (MacKenzie, Nicklas, Waldfogel, &

Brooks-Gunn, 2013). Measures of externalizing behavior and receptive vocabulary were assessed at age nine. Results indicated that those children who were spanked at least twice a week by their mothers scored 2.66 points higher on a measure of aggression and rule-breaking than those who were never spanked. Additionally, those who were spanked less, still scored 1.17 points higher than those never spanked. When fathers did the spanking, those spanked at least two times per week scored 5.7 points lower on a vocabulary test than those never spanked. This study revealed the negative cognitive effects of spanking in addition to the increase in aggressive behavior.

Internationally, physical discipline is increasingly being viewed as a violation of children’s human rights. Thirty countries have banned the use of physical punishment, and the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (2014) called physical punishment “legalized violence against children” and advocated that physical punishment be eliminated in all settings.

Many alternatives to spanking are advocated by child development specialists and include:

- Praising and modeling appropriate behavior

- Providing time-outs for inappropriate behavior

- Giving choices

- Helping the child identify emotions and learning to calm down

- Ignoring small annoyances

- Withdrawing privileges