Reach: Generating Awareness and Attracting Visitors

Pierre-Yann Dolbec

Overview

In this chapter, we cover the strategic bases associated with the Reach stage. We start by covering the main objectives of the Reach stage and some KPIs associated with goals for consumers. We then move our attention to discussing paid media activities. To do so, we first emphasize the necessity of building landing pages whenever we are creating marketing campaigns and describe what landing pages are. We then turn our attention to the online ecosystem, discussing elements such as types of paid media activities (e.g., banner advertising, search advertising, affiliate marketing, and influencer marketing) and expand on payment models and types of targeting that the new online ecosystem allows.

Learning Objectives

Understand the Reach stage, landing pages, different paid media activities, and key terms associated with payment models and targeting approaches.

Reach

Reach is the first stage in the RACE framework. It entails the publication and promotion of content in order to draw visitors to our website. The two main objectives at this stage are to build awareness (about your website, brand, products, and/or services) and to bring visitors in. We do so by using both inbound and outbound marketing activities (although we will concentrate on the latter in this chapter) and through paid, owned, and earned media touchpoints.

The goals we have in mind for people at this stage might include for them to come to our website from a SERP, stay on our website once there, or click on our ads. Internally, we can have objectives like creating high-ranking pages and ads with a good ad score (briefly, an ad quality score can lead to lower prices for your ads and better placements on SERPs).

Accordingly, examples of KPIs that are important at this stage include number of unique visitors, bounce rate, clickthrough for ads, page authority, page rank, and ad quality score.

In the rest of this chapter, we will cover outbound marketing activities. Since you should Never Start A Marketing Campaign Without a Dedicated Landing Page (NSAMCWADLP), we start our review of paid marketing activities by digging deeper into landing pages.

Landing Pages

A landing page is a campaign-specific page distinct from your main website that has one goal and one link (ideally, a call to action).

- Campaign specific: It is associated with a specific campaign. Ideally, you might also want to create specific landing pages for specific ads. This allows you to better optimize conversion rates by practicing some strategies we will cover during the Convert stage.

- Distinct from your main website: you cannot access it from any page of your main website, but it is still hosted on your domain (e.g., www.yourdomain.com/landing-page-campaign-A).

- One goal: Visitors should be able to achieve one thing and one thing only. We will see shortly that landing pages can have as an objective either to acquire leads or to redirect visitors to some specific section of your website.

- One link: There is only one link that consumers can click on that page.

Types of Landing Pages

Two main types of landing pages exist.

- clickthrough landing page

- The goal of this landing page is to have visitors visit a specific section of your website.

- It is generally a sales pitch to warm visitors up to what is to come.

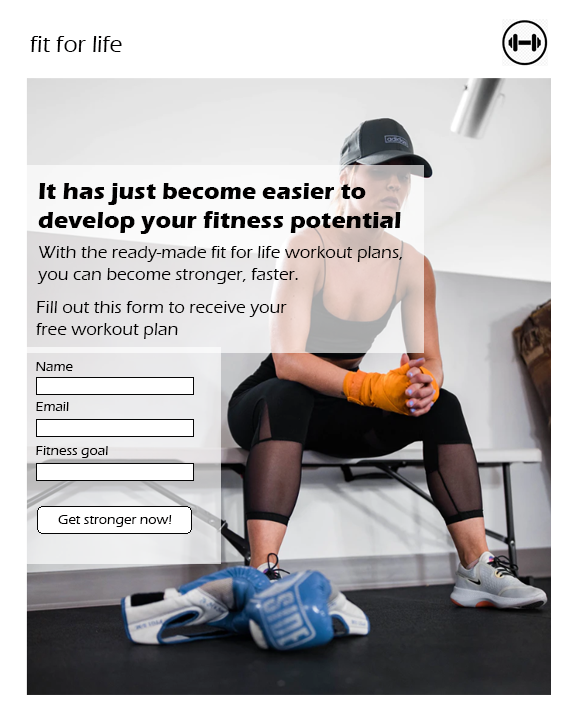

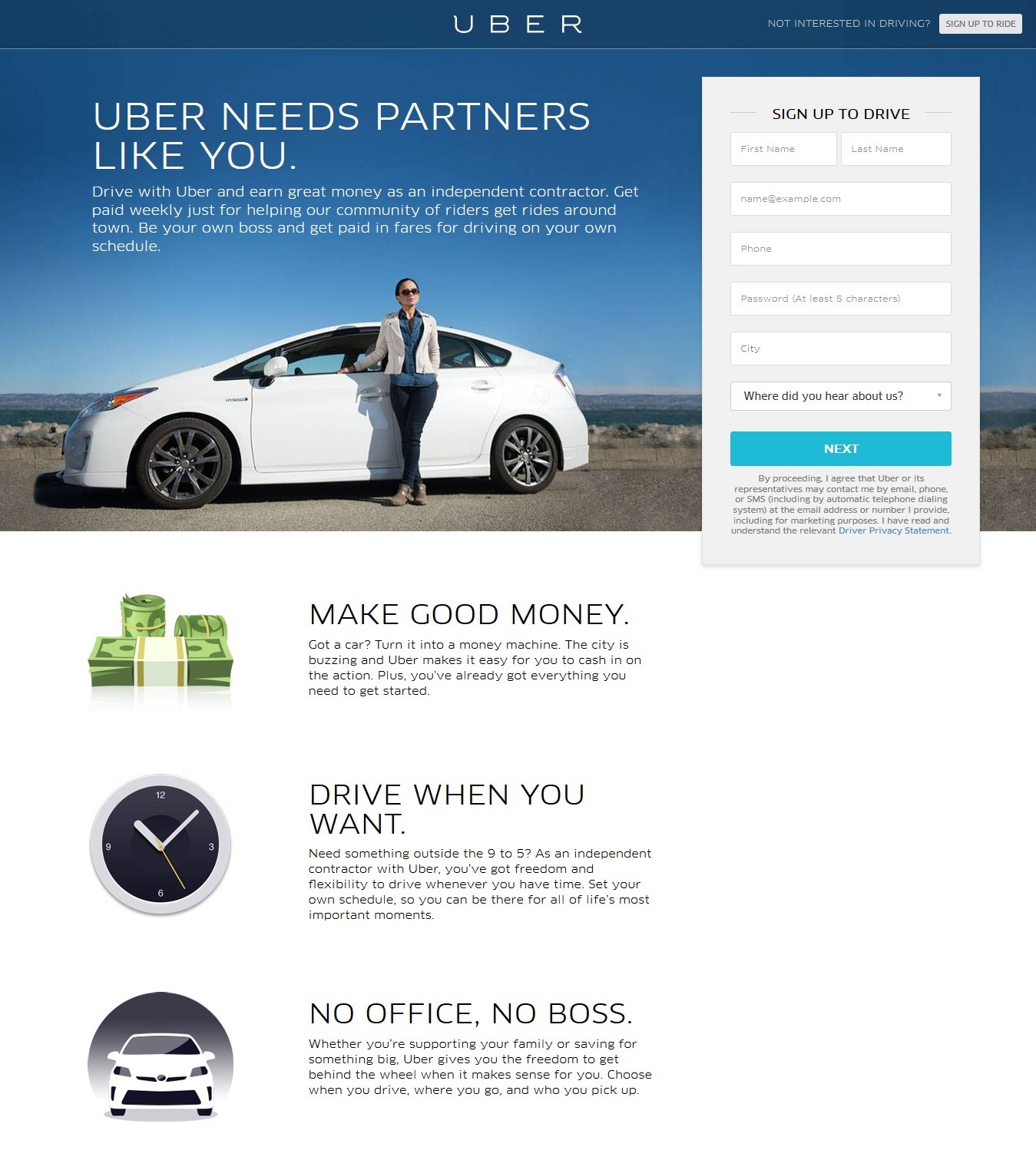

- lead generation landing page

- Your objective here is to generate leads, and the goal for people on this landing page is to give you their personal information (e.g., email address).

- It is thus typically a form-based page.

- Sometimes, an email address is offered in exchange for some piece of content or a free service, like a white paper, a webinar, a free consultation, a discount, a contest, a free trial, or the opportunity to order a product before others.

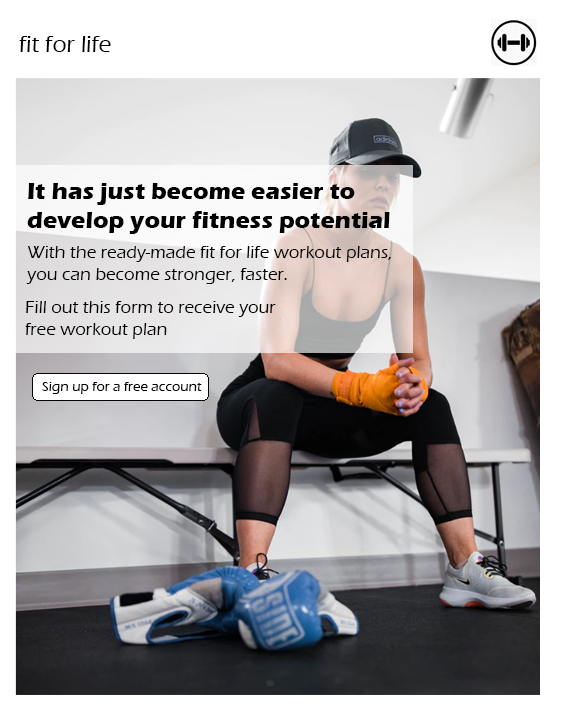

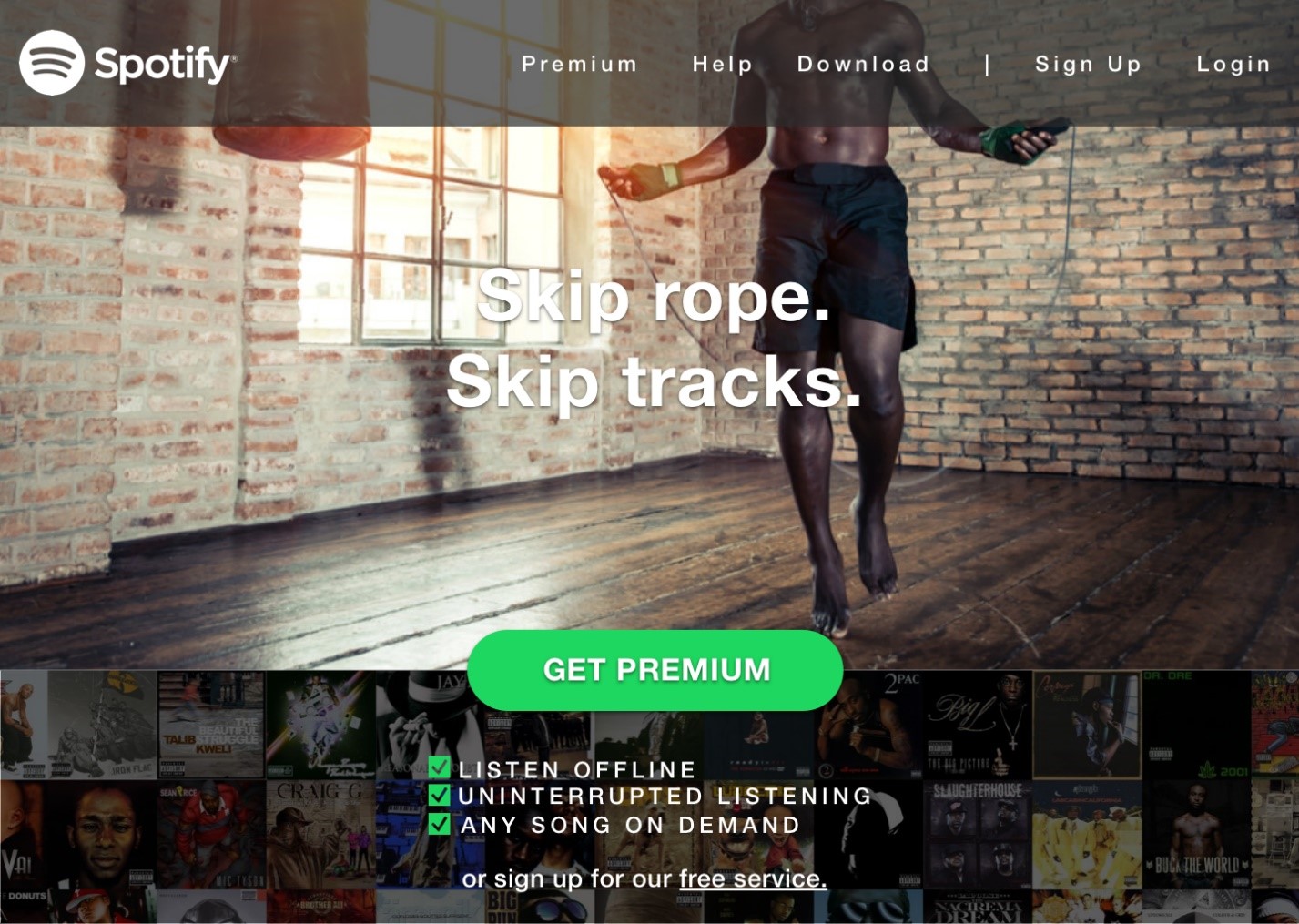

Figures 5.1 and 5.2 present examples of clickthrough landing pages, and Figures 5.3 and 5.4 present examples of lead generation landing pages.

Why Use Landing Pages?

Ad campaigns can aim at building awareness, but they are typically associated with making consumers achieve specific goals, such as trying out software for free, registering for an account, sending an email to a company, or downloading a free piece of content.

When running ads that have such goals, sending visitors to a website is counterproductive: a website is not meant to convert, i.e., to make consumers achieve a specific goal. If consumers are directed to a website, they will be faced with hundreds of potential actions (associated with the links available on a website), one of which is the action they should be performing. It becomes easy for consumers to get lost.

Inc comparison, landing pages are focused on help consumers achieve only one goal. They facilitate conversion. They do so by allowing to tailor the page to the exact goal that users should accomplish. This can be achieved, for example, by offering a clearer message to consumers (vs. bringing consumers to a website), by minimizing the potential actions they can perform on the page, and by matching the visuals of an ad with that the landing page. We will delve in depth into some of these benefits of landing pages when discussing conversion optimization in chapter 10.

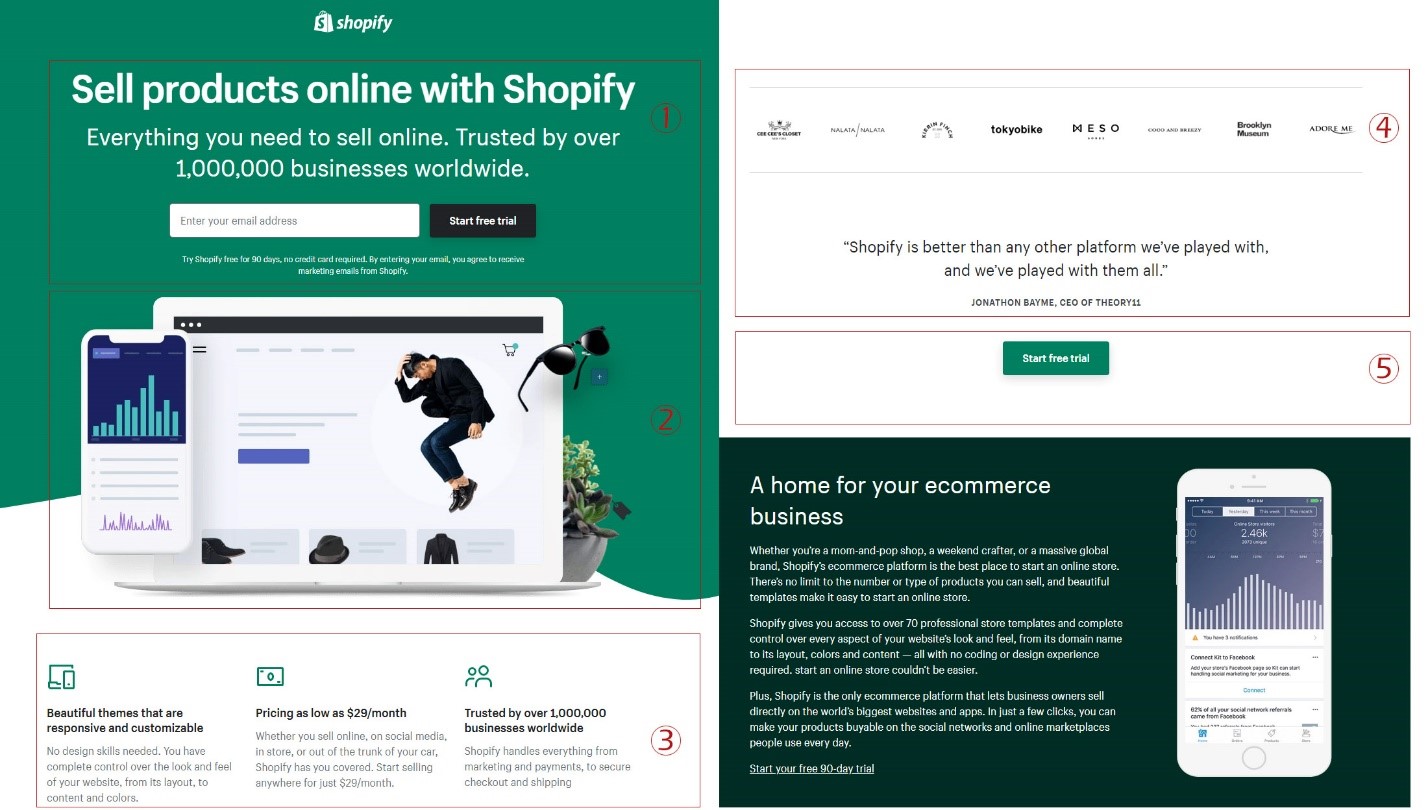

Take, for example, the ad for Shopify shown in Figure 5.5.

The goal for consumers associated with this ad is to try Shopify for free and create an online store today. How can we maximize the chances that consumers will do so?

When creating this ad, the question that a digital marketer faces is: where do I bring visitors? Ideally, you want to bring visitors to a place that will ensure that they will achieve the goal of trying Shopify.

A first option could be the homepage of Shopify shown in Figure 5.6.

Although this page has a box at the very top that incites people to try out Shopify for free, visitors are also offered a wide array of competing actions. They can click any of the links at the top of the page (“Start,” “Sell,” “Market,” “Manage,” “Pricing,” and “Learn”); they can scroll down to learn more about Shopify, and at the very bottom, they can also access information such as “About” Shopify and “Terms and Conditions.” In short, they can do a lot more than simply trying Shopify for free.

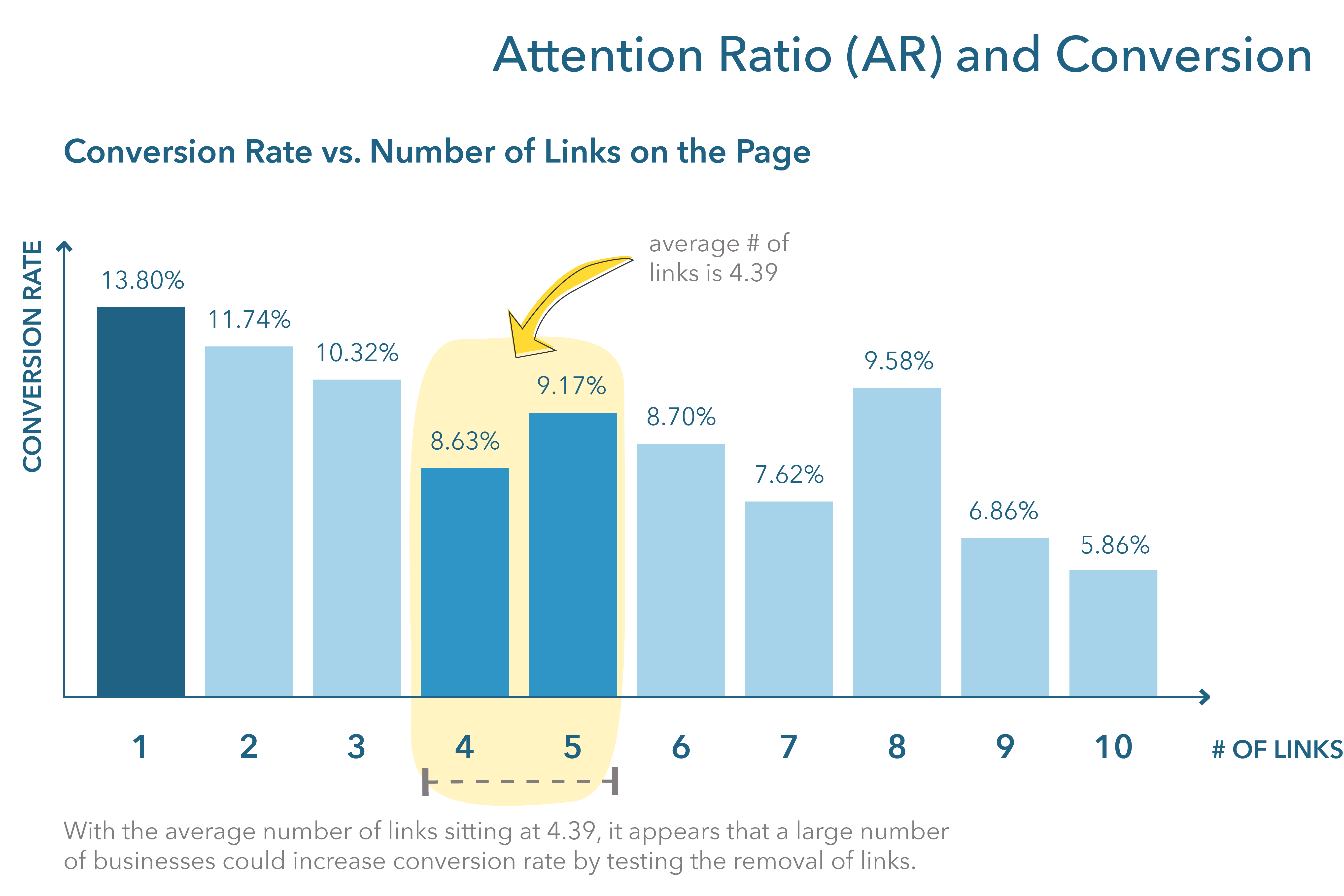

Over time, digital marketers have learned that one of the easiest ways to ensure that visitors will do what you want them to do is to limit the possibilities to just the one action you want visitors to take—in this case, signing up to try Shopify for free. The chart in Figure 5.7 exemplifies this by showing the conversion rate vs. the number of links on a page.

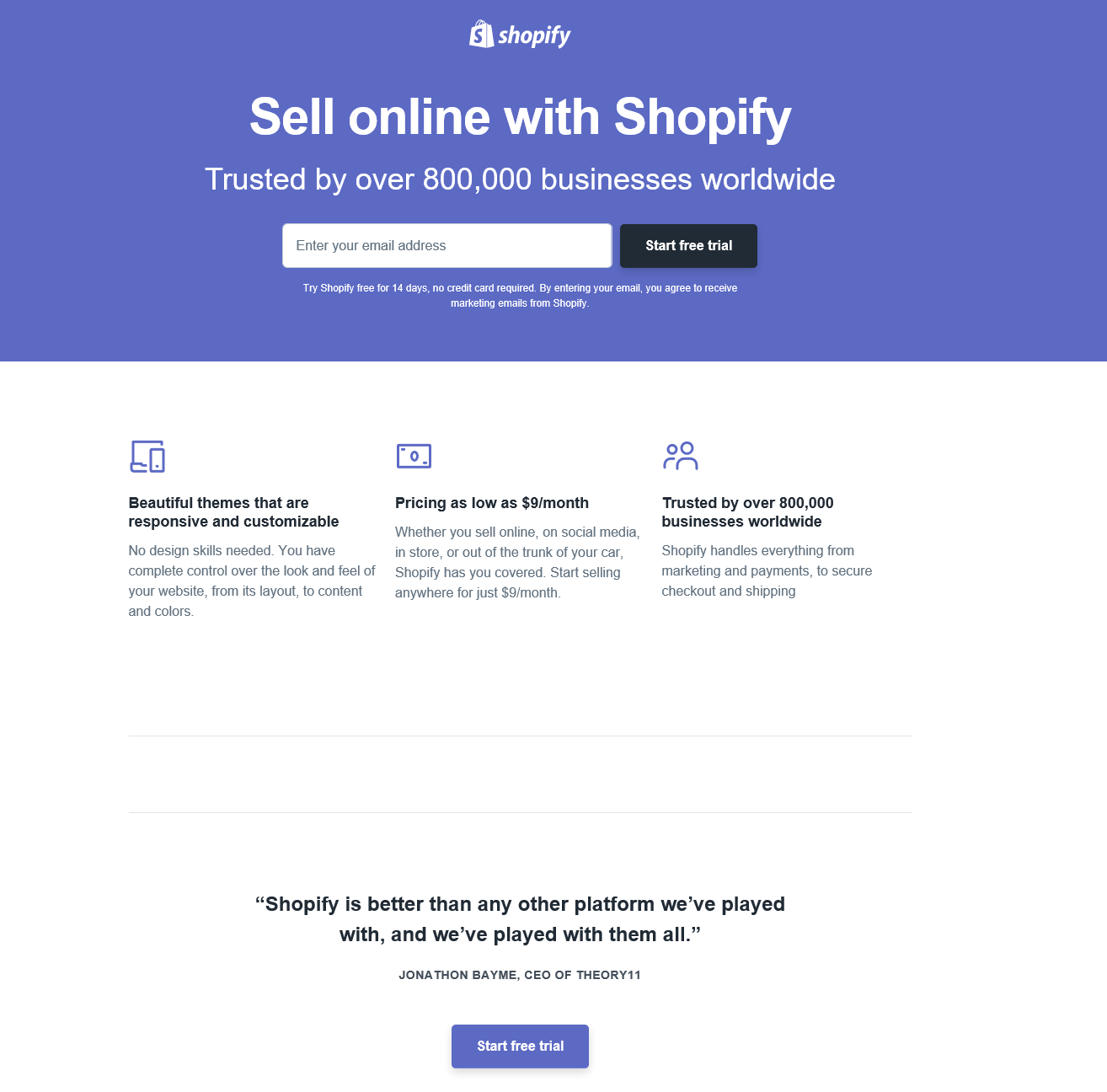

For this reason, the Shopify ad doesn’t redirect consumers to the Shopify homepage. Rather, they created a dedicated landing page where the only possible thing for visitors to do after clicking the ad is to start their free trial. Figure 5.8 shows the landing page.

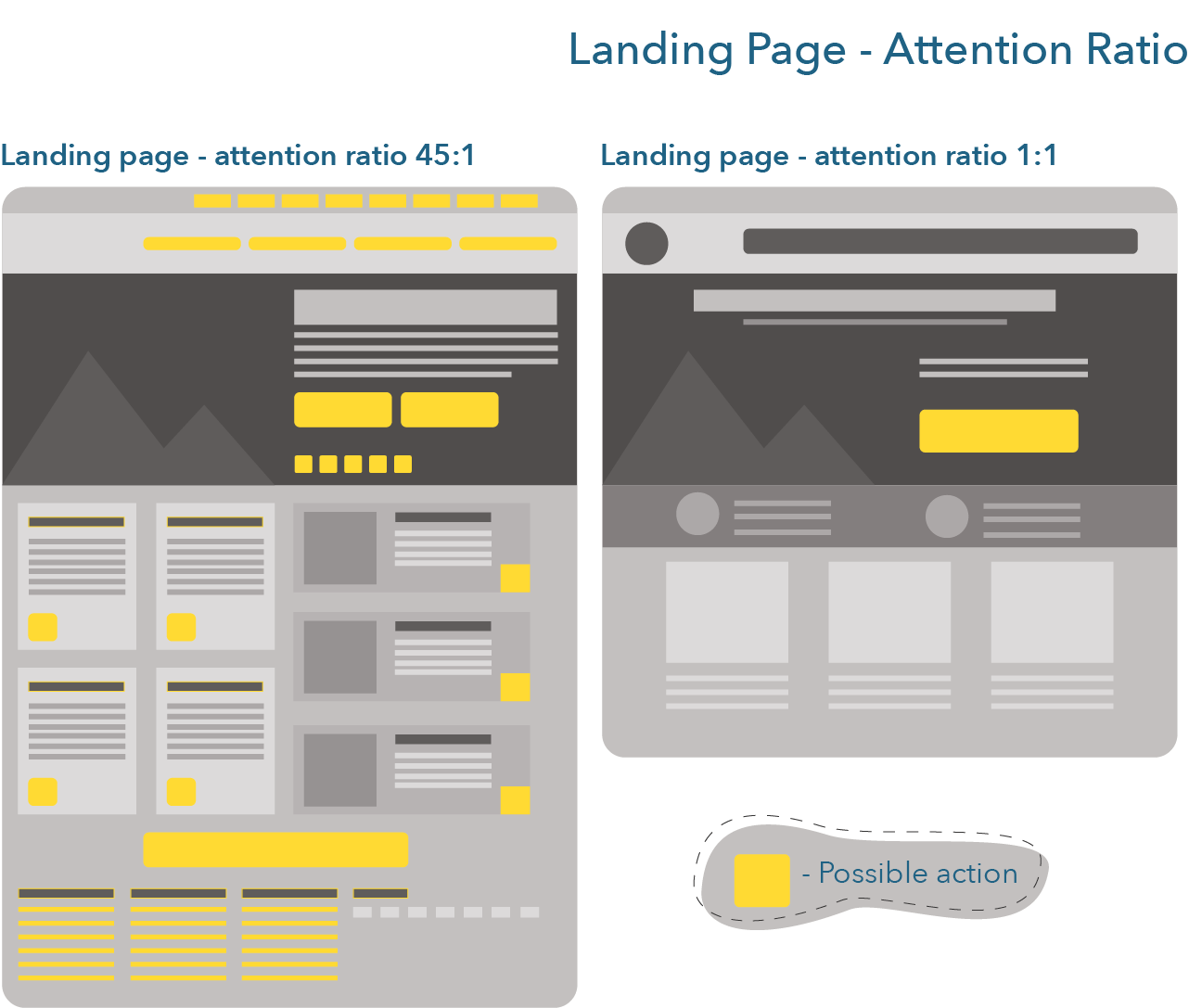

By focusing visitors’ attention to the task at hand (i.e., trying Shopify for free), we can maximize the conversion rate, i.e., the number of visitors who will achieve the goal we want them to achieve. A metric created to better understand the relationship between the number of possible actions on a website and the number of goals for consumers is the attention ratio. Figure 5.9 demonstrates how a website has a high attention ratio (i.e., many possible actions vs. what you want consumers to be doing) and why a landing page is ideal for pushing visitors to perform the action we want them to perform. Landing pages should have an attention ratio of 1:1, meaning one possible action to one goal.

Building a Landing Page

A landing page has five basic elements: First, a unique selling proposition (USP), a “unique” benefit offered by the product or the service (I put unique in quotation marks because companies usually present a benefit without it being unique). The USP is typically communicated through a headline and a subheadline that explain the value and purpose of the product or service. It is also sometimes reinforced in a mid-page statement and a closing argument at the bottom of the page. Second, a hero shot, which is a visual associated with the product or service. Third, a benefit statement that explains how the product or brand helps consumers, typically using bullet points or small paragraphs. Fourth, social proofing such as testimonials, awards, client list, or media logos, and finally, fifth, one link, typically a call to action.

Let’s see these five elements in a recent Shopify landing page (Figure 5.10).

Paid Media Activities

Digital marketers typically advertise online through advertising networks, such as Google AdSense, and advertising exchanges, such as Google AdX (the differences between these are summarized succinctly here but are outside of the scope of this course). Although these two approaches to providing advertising space to advertisers differ, from an advertiser’s perspective, both provide an entry point where advertising space can be purchased. Networks, for example, aggregate ad space across websites and sells this inventory to advertisers.

Nowadays, much of advertising space is sold through programmatic buying, the automated purchasing of digital advertising space. When marketers purchase space through the Facebook Ads or Google Ads platforms, for example, they are making use of programmatic buying. These platforms have been transformed in recent years by the use of algorithms and predictive analyses to help identify the optimal placement of ads to reach specific objectives. Facebook Ads, for example, gives advertisers options such as reach, awareness, or lead generation campaigns. Choosing a specific objective will influence where ads will be placed (i.e., who will see the ads) to maximize the effectiveness of the ad campaign.

We now turn our attention to different ways of reaching customers. More precisely, we will briefly cover banner advertising, search advertising, social media advertising, affiliate marketing, and influencer marketing.

Banner Advertising

Banner ads are images or animations that advertise brands, products, and services on websites. They can be likened to the ads one would find in newspapers and magazines. Many types of banner ads exist, including the following:

- standard banners: standard sizes (measured in pixels) for static, animated, and rich media banner adverts

- interstitial banners: shown between pages on a website or, more often, between screens on an app

- pop-up ads: pop up, or under, the webpage being viewed; open in a new, smaller window

- floating adverts: appear in a layer over the content but not in a separate window

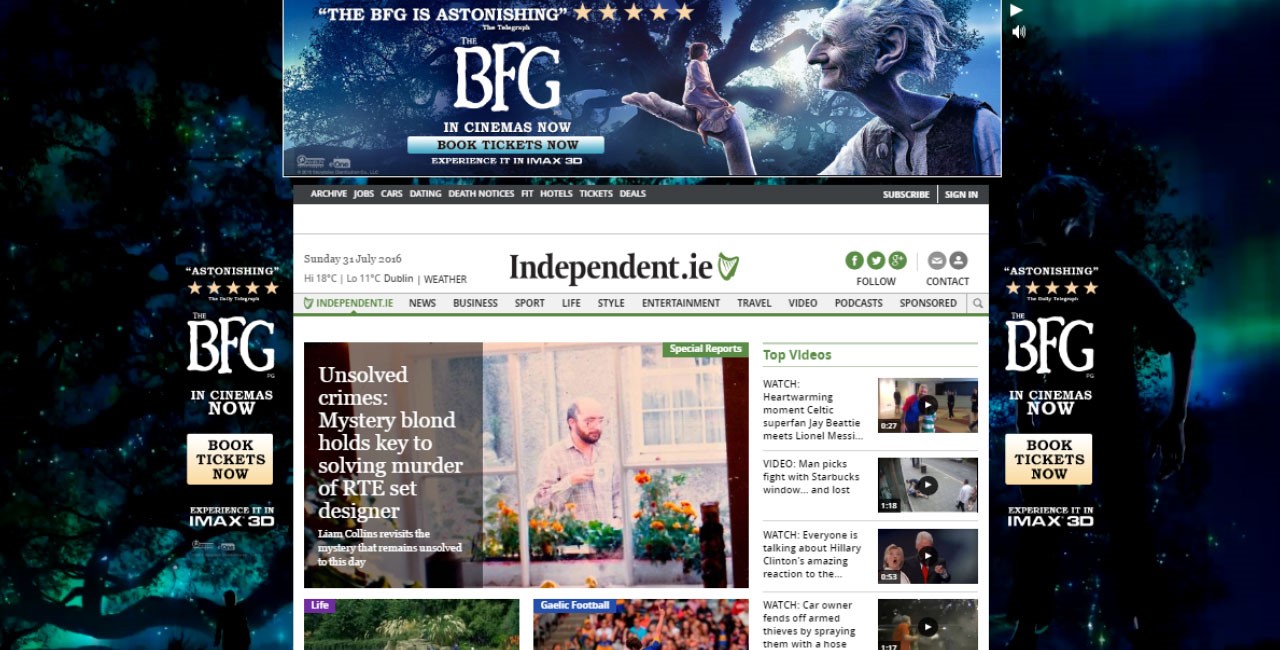

- wallpaper adverts: change the background of the webpage being viewed; may be clickable

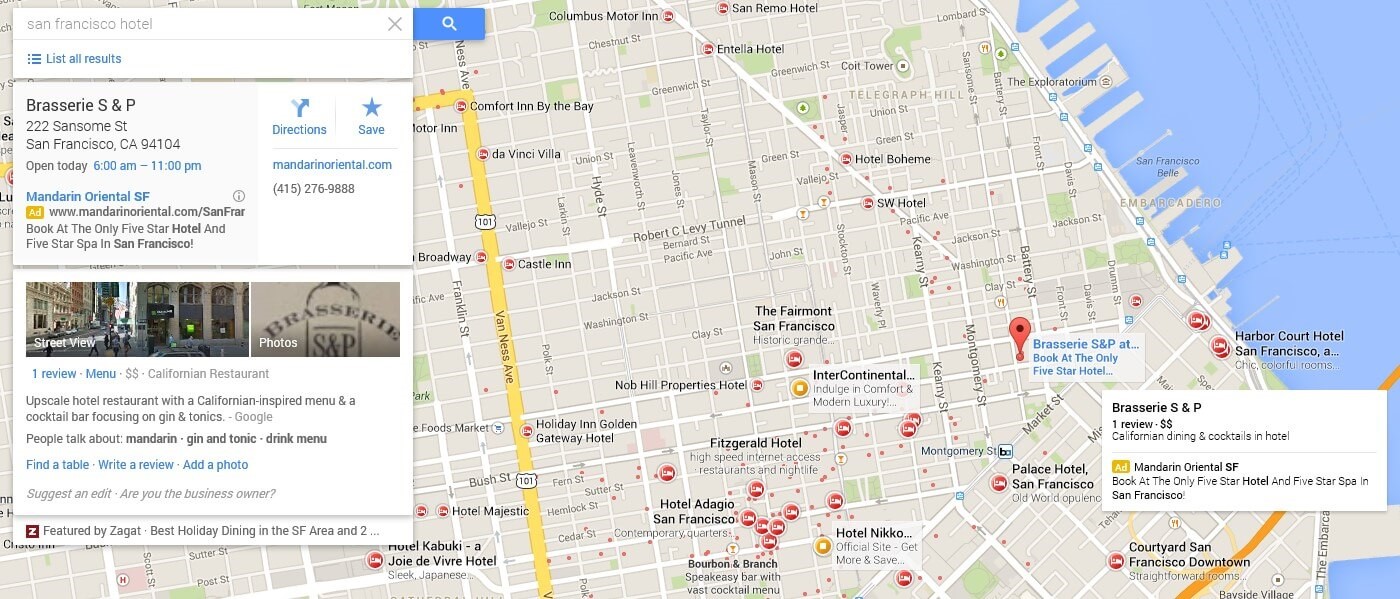

- map adverts: placed on an online map, such as Google Maps; usually based on keywords

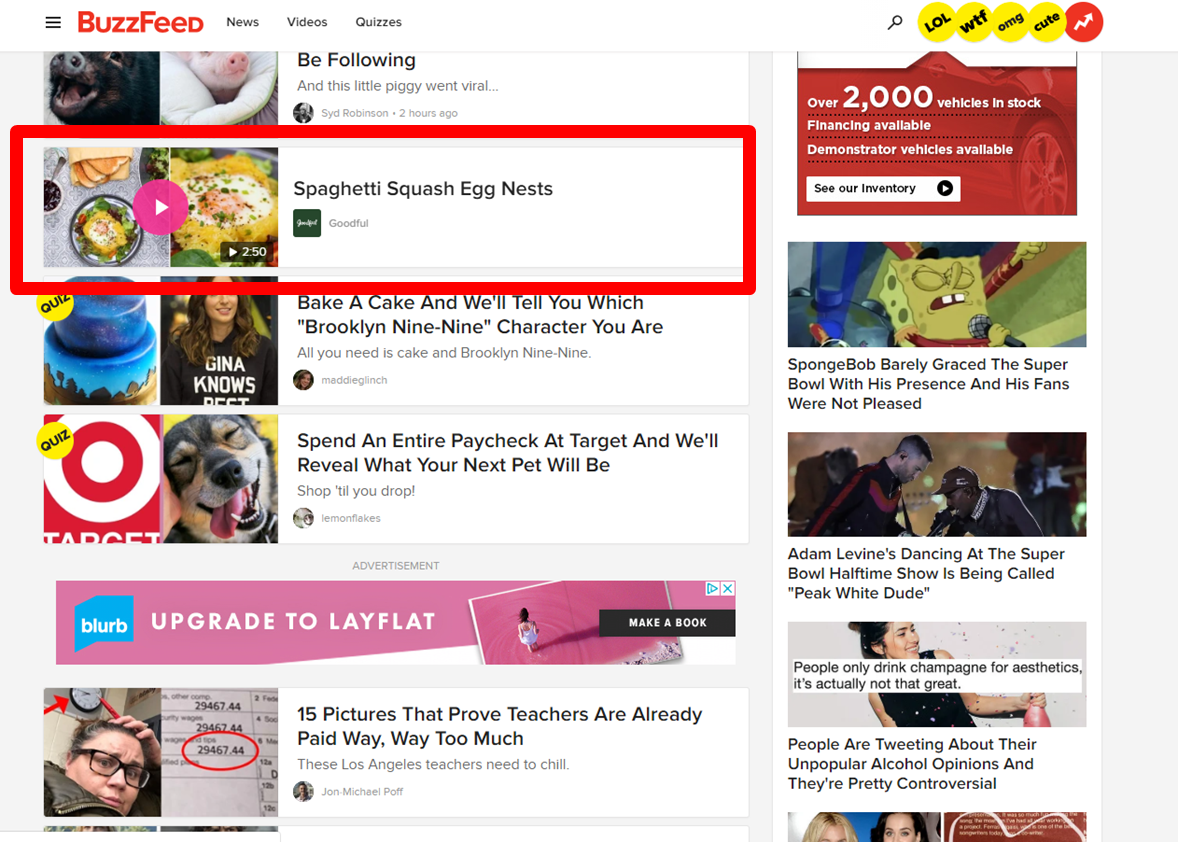

- native content ads: the online version of advertorials, where the advertiser produces content that is in line with the editorial style of the site but is sponsored or in some way product-endorsed by the brand

Figure 5.11 shows an example of a standard banner ad.

Figure 5.12 shows an example of an interstitial banner ad.

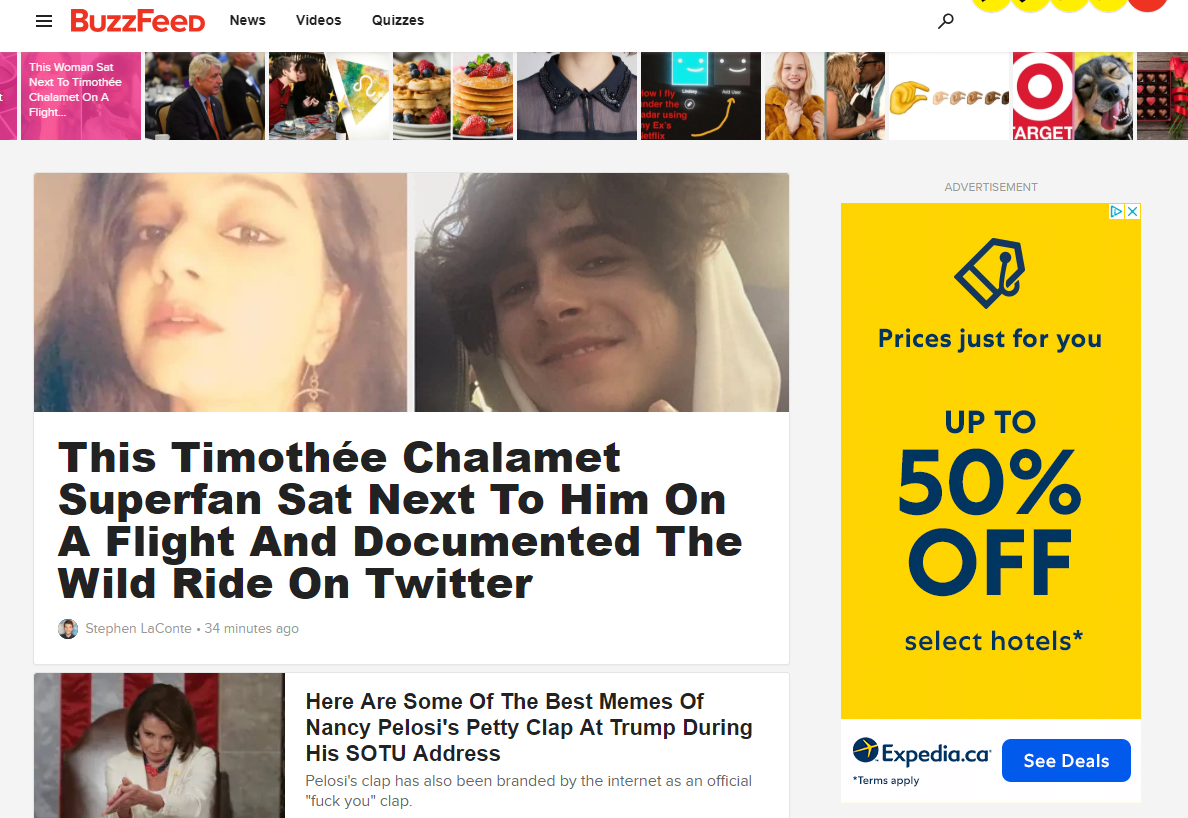

Figure 5.13 shows an example of a pop-up ad.

Figure 5.14 shows an example of a floating ad.

Figure 5.15 shows an example of wallpaper ad.

Figure 5.16 shows an example of a map ad.

Figure 5.17 shows an example of a native ad.

Search Advertising

In comparison to SEO, search advertising entails gaining traffic on SERPs by bidding on keywords. Search advertising is also referred to as PPC advertising because of the mode of payment: Advertisers typically pay search engines for each click their ad receives.

Search ads are sold and delivered on the basis of keywords. Advertisers decide on sets of keywords they would like their ad to show up for, and when users search for these terms, their ad might show up. Keywords are sold through an auction process. As a result, industries with very high customer lifetime value, such as insurance or mortgage firms, can pay upward of $50 per click.

To better understand how to bid for keywords, let’s watch the following video, which explains how the Google search ad auction works.

Using search ads requires combining three main elements: the keywords you want your ad to show for, your ad (i.e., a headline or two, a URL, and a description), and a landing page. In short, you buy keywords that will be used by a search engine to display your ad when people search for those keywords. Your ad needs to be relevant to the search and attractive to the consumer. When your ad is clicked, you direct consumers to your landing page.

The guidelines for writing effective search ads are similar to those for writing effective page titles and meta descriptions. This is the only element that users will see on SERPs, and it is therefore important to make it as attractive as possible. First, the ad should ideally target a clear need or goal that consumers have, dependent on where they are in their journey. Is the consumer looking for information? Comparison tools? To purchase something? How can your ad help the consumer achieve their goal? Second, the ad should have a clear call to action.

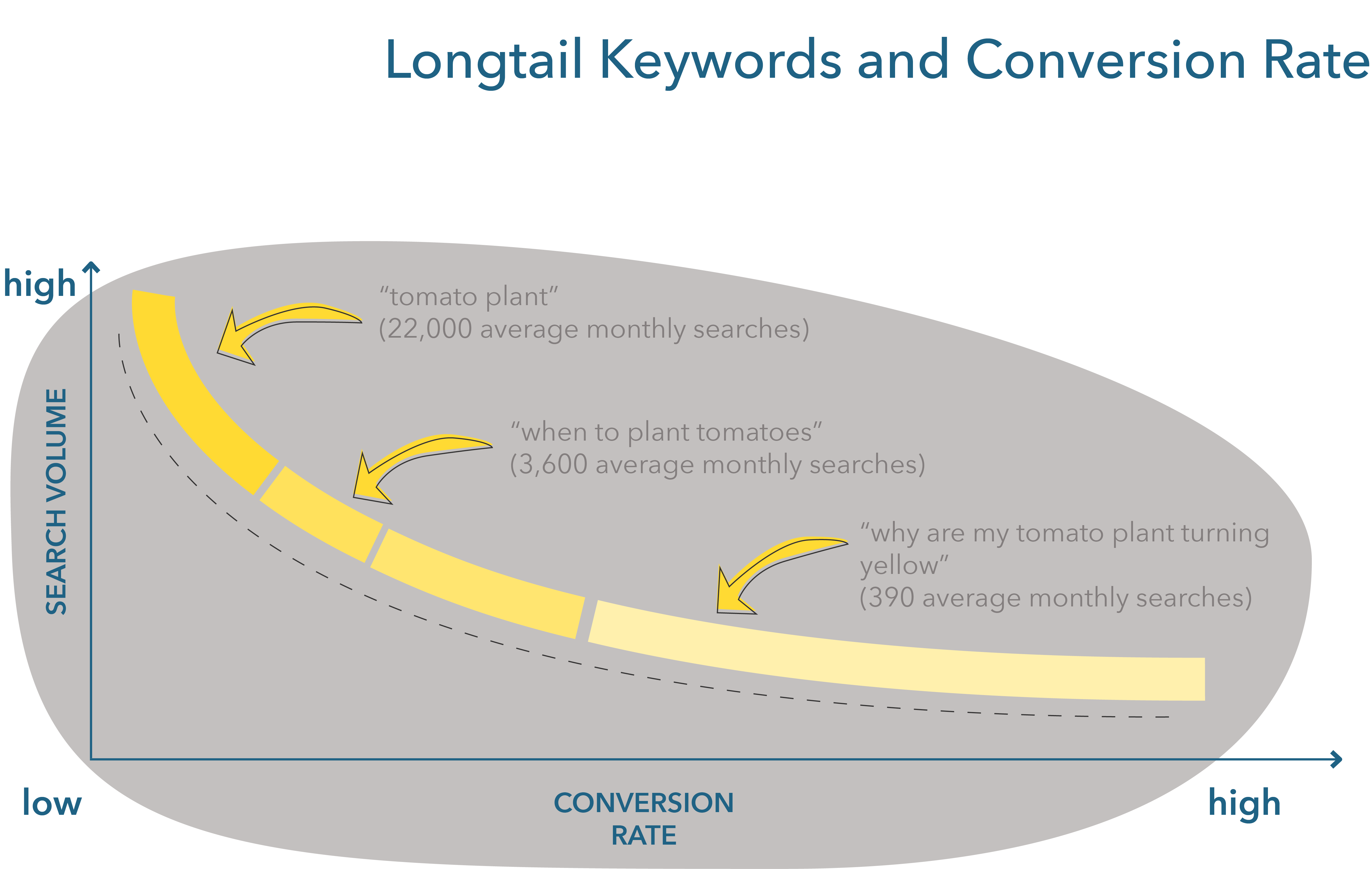

Searches follow a long-tail distribution (Figure 5.18; text description here). This has implications when doing search ads: Most consumers might be using generic, high-volume keywords, while others might be using hyper-precise, low-volume keywords. Although bidding on high-volume keywords might seem like a good strategy, it comes with drawbacks. First, these keywords are likely more expensive. Second, they are less likely to bring quality traffic. By quality traffic, I mean visitors who can eventually become your customers. This is particularly important for search advertising, because each visitor is associated with a specific cost. Devising effective search advertising campaigns thus entails balancing volume and quality: Bringing in enough visitors that can buy your product or service but making sure that visitors who won’t buy it don’t click on your ad.

To do so, firms typically combine high-volume and low-volume keywords to tailor their search ads to visitors who can potentially be customers. This helps lead generation efforts down the line while ensuring more cost-effective search ad campaigns.

After deciding on keywords, you can choose how keywords will be matched to specific searches. Four main types of match exist: broad match, phrase match, exact match, and negative match.

A broad match shows your ad for any search that contains the keyword(s) you are bidding on, and any other keyword in any order, as well as variations on your keywords such as misspellings, synonyms, singular and plural forms, stemming (e.g., a search for “flooring” will match “floor”), related searches and other variations.

For example, let’s assume you are bidding on the keyword “kitten” using a broad match. Any search containing a variation on “kitten” would show your ad, such as “kittens,” “kitten photos,” or “adopt a kitten.”

Associated with broad match are broad match modifiers, which allow more control over matches by including some other necessary keyword. For example, if you want your ad to be shown only for searches that contain both “adopt” AND “kitten,” you can specify that. Your ad could then show for searches such as “adopt a kitten,” “how to adopt a kitten,” or “best kitten to adopt.”

Phrase match shows your ad only for searches that include the exact phrase (or close variations of that exact phrase with additional words before or after). For example, let’s assume you are bidding on the key phrase “how to adopt a kitten.” Your ad could show for searches such as “how to adopt a kitten now” or “best ways how to adopt a kitten.”

Exact match only shows your ad for searches that use the exact phrase, or close variations of it, and no other words. For example, the key phrase “adopt a kitten” will match the searches “adopt a kitten” and potential misspellings (e.g., “adopt a kitten”).

Negative match prevents your ad from being shown when certain keywords are included, such as keywords that might cater to customers searching for a different product. For example, let’s say you’re an optometrist who sells eyeglasses. In this case, you may want to add negative keywords for search terms like “wine glasses” and “drinking glasses.”

A few metrics that are important for evaluating your success when doing search advertising include the following:

- clickthrough rate (CTR): the percentage of impressions that turn into clicks (clicks/impressions)

- conversion rate: the percentage of clicks that turn into conversions (conversions/clicks)

- cost per click (CPC): the amount of money you’re spending on each click (spend/clicks)

- cost per acquisition (CPA): the amount of money you’re spending on each conversion (spend/conversions)

Social Media Advertising

Social media has become central to most consumers’ lives. In some countries, social media networks have become synonymous with the internet, to the point where “many use the internet without realizing it” (Pew 2019). Social media has also fueled consumer content co-creation efforts (or “user-generated content”), and we can now publish our own content and share the content of others. Many social media businesses rely on the work of consumers (e.g., without us posting content and images, there would be no reason to use Instagram or Facebook).

There are many platforms for advertising on social media, with new ones accumulating millions of users in ever-shortening periods of time (TikTok being a prime example of the latter). As we favor a strategic outlook, a review of all existing social media platforms is outside of the scope of this chapter, but the following links give precise instructions on how to post an ad on each of the major ones:

The variety of social platforms has an important implication when using them to advertise: the importance of understanding social and visual norms in order to create impactful campaigns. Social norms refer to what is considered acceptable behavior on a social platform. Understanding the social customs, shared actions, and behaviors that are standard for a platform is also important. Marketers that understand these have been able to create successful campaigns around them, such as the Guess #inmydenim campaign that used the “transformation” trend, the #JLoTikTokChallenge that used the challenge customs, and the Doritos #CoolRanchDance campaign that leveraged TikTok dances and the capabilities of the platform of using songs.

This approach of capitalizing on norms and customs is found throughout social media platforms. Old Spice, for example, tailored its advertising efforts to each platform and offers many good examples. The brand created one of the first iconic ad campaigns by emphasizing two-way interactions and video sharing capabilities on YouTube, with a response campaign associated with their ad “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like.” They translated the Twitch Plays Pokémon phenomenon, where thousands of users direct video gamers to perform certain actions to create a campaign where Twitch users could control the actions of a man for three days for the Nature Adventure campaign. And they used the idea of gif wars on Imgur and the platform’s upvote capability to create the Smellmitment campaign.

These campaigns all followed the same precepts: They engaged with the norms and customs of the platform they used. They created ads that aimed to generate a conversation with users rather than solely talking about the product. And they leveraged the technological specificities of each platform (e.g., songs for TikTok, turning comments into controller inputs for Twitch, and using upvotes on Imgur).

Social Media and RACE

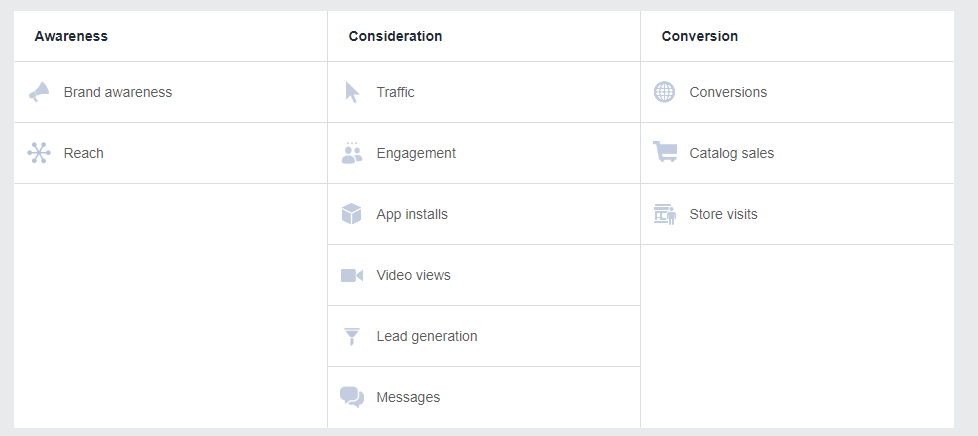

Social media has also become one of the main pillars for advertising, and it can support most of the objectives of the different stages of the RACE framework. That is, using social media for advertising can help with increasing awareness, bringing visitors, creating leads, converting leads to customers, fostering loyalty, and engaging customers in co-creation activities. This is well exemplified by the social media ad objectives that most platforms ask you to choose from when starting an advertising campaign. Take, for example, Facebook ad objectives (Figure 5.19; text description here).

Facebook has divided its ad objectives into three categories that almost perfectly align with the RACE framework: “Awareness” is associated with Reach, “Consideration” with Act, and “Conversion” with Convert. Let’s examine each objective in more detail.

Under the Awareness category, brand awareness “increases overall awareness for your brand by showing ads to people who are more likely to pay attention to them,” and reach “shows ads to the maximum number of people in your audience while staying within your budget.”

What is the difference? While both align with Reach objectives, brand awareness is designed to help advertisers find the audiences most likely to recall their ads. The goal is to increase brand recall, and this ties to Facebook “Estimated ad recall lift.” Reach maximizes the number of unique people who will see your ad while capping the frequency of impressions (e.g., one a day).

Objectives in the Consideration category overlap with all three stages.

Traffic addresses a Reach objective as it aims to grow “the number of people who are visiting your site, app or Messenger conversation,” but it is also associated with Act because it aims at “increasing the likelihood they’ll take a valuable action when they get there.”

Engagement can be seen as both an Act and an Engage activity: it wants to “get more people to follow your page or engage with your posts through comments, shares and likes. You can also choose to optimize for more event responses or offer claims.”

App installs can be seen as both Act and Convert activities (depending on the strategic goal of having people install your app; if the app is free and purchases happen within it, it’s a lead generation activity; if it is a paid app, it’s a convert activity).

Lead generation includes a menu where users can directly enter their personal information. It is an Act activity that aims at creating leads.

In the last category, Conversion ads align with the Convert stage by helping advertising to convert users into customers.

These categories use the Facebook ad delivery algorithm differently, with Awareness objectives targeting ads to people more likely to respond to Awareness generation and Conversion objectives to people more likely to convert. Some objectives also offer specific types of ads, such as a catalog (catalog sales), a form (lead generation), or a redirection to app installs (app installs).

The last important strategic piece to cover associated with social media is their targeting capabilities, or how they allow you to display ads to specific groups of people. All platforms will allow you to target your ads based on key customer variables, such as demographics, location, and interests, and each also has some specific targeting capabilities. For example, LinkedIn allows you to use LinkedIn audience segments to programmatically reach professional audiences based on their company size, seniority, professions, and other key professional variables.

Most platforms allow for behavioral targeting, where ads are delivered based on purchase behaviors or intents or people who have a specific kind of connection to your page, app, group, or event. For example, advertisers could target any users that have engaged with their content across the Facebook family of apps and services.

After Facebook introduced the highly useful Lookalike audience option in 2013, other major advertisers such as Google followed suit. Lookalike audiences use platforms’ algorithms to create groups on social networks that resemble other groups. This is a new and unique way to target that was never before possible and can help companies unearth some group of consumers who would be highly qualified but have not yet been identified by the company. A lookalike audience could be based on a previously highly engaged audience (i.e., finding another group of consumers that shares some commonalities that will also make them highly engaged) or an existing segment of customers.

Payment structures for social media advertising are typically one of the following:

- CPM (cost per thousand): Pay every time 1,000 users view your ad.

- CPC (cost per click): Pay when a user clicks on your ad.

- CPA (cost per action or cost per acquisition): Pay only when an advert delivers an acquisition after the user clicks on the advert (definitions of acquisitions vary depending on the site and campaign and may be a user filling in a form, downloading a file or buying a product).

Influencer and Affiliate Marketing

Influencer marketing—a form of social media marketing that capitalizes on people or organizations with large followings who exert some sort of influence over others because of their expertise or charisma—has become both a marketing and a societal phenomenon. There were more than 3.7 million ads by influencers on Instagram in 2018, and some estimate that the market will reach US$10 billion by 2020 (Wired 2019). Ninety percent of Instagram campaigns in 2018 used micro-influencers, influencers who have somewhere between 1,000 and 100,000 followers (HubSpot 2019). Micro-influencers represent about 25% of the Instagram user base, or about 250 million people (Mention.com 2018). While most micro-influencers charge a few hundred dollars per post, top ones can charge upward of US$50,000.

Although influencers can be used throughout all RACE stages, they historically have been used as an awareness generation channel. Even today, most of the main objectives reported by brands for the use of influencers relate to the Reach stage, such as improving brand awareness, share of voice, reaching new audiences, and managing reputation (Fipp 2017). Over the last few years, there has been a trend toward moving marketing budgets away from top influencers to micro-influencers, who are believed to have a stronger connection with their followers and thus generate stronger engagement (Wired 2017).

Ideally, when planning for an influencer campaign, firms should aim to choose influencers who correspond to the size of their business. It is easier for smaller firms to create relationships with micro-influencers, and these individuals might support the firms’ goals if a trusting relationship can be established. To facilitate the internal management of influencer campaigns, it can be useful to create influencer personas, i.e., personas that represent the kind of influencer the firm should aim to recruit for their campaigns. Firms should aim to find influencers that align with their brand identity, can resonate with the brand’s customers, and can help the firm achieve their objectives (i.e., perhaps different influencers can help achieve different objectives, whether it is reaching a wide number of consumers, generating leads, or converting leads to customers). Firms should also support influencers’ efforts by providing marketing materials. Some influencers might want to work with firms to align the firm’s interests and objectives with theirs. For example, many influencers report only taking on clients that represent their values or whose products they already like. When choosing influencers, ask yourself:

- Who are their followers? Are their followers my targets?

- Are they real?

- Do they release quality content? (That can be matched with your product?)

- Have they worked with your category? With a competitor?

- Do they promote products often? How do their followers react?

- What platforms are they on?

- Can you use their content?

- How long does their content stay online?

Two main routes exist for recruiting influencers: using influencer agencies, networks, or platforms, which centralize interactions between a firm and many influencers or contacting influencers directly. If reaching out directly, make sure to send personalized messages that clearly show that you understand who the influencer is and why you see a fit between your brand and the influencer’s brand. Different influencers have different goals: some might want to push products they strongly believe in, some might want to be a positive influence on their followers, and some might be in it for the money (Kozinets et al. 2010). This should play a role in how you “sell” your campaign to an influencer.

The main payment structure for influencers is pay per post, which varies depending on the domain or the influencer. In 2017, according to influence.co, payments averaged US$217 per post, which could be broken down as follows, with influencers with fewer than 1,000 followers commanding 83$ per post and those with more than 100,000 followers, 763$ per post. Posts mediated by The Influence Agency cost more, ranging from 2,000$ to 10,000$ per post by influencers with more than 100,000 followers. Blog collaborations are priced by the number of monthly impressions the blog receives:

- 10,000 monthly impressions: 175$

- 100,000 to 500,000 monthly impressions: 500$

- 500,000+ monthly impressions: 1,000$ to 5,000$

Other payment structures include pay per lead, pay per engagement (when a user performs an action associated with a post, such as a click, a comment, or a share), or pay per view.

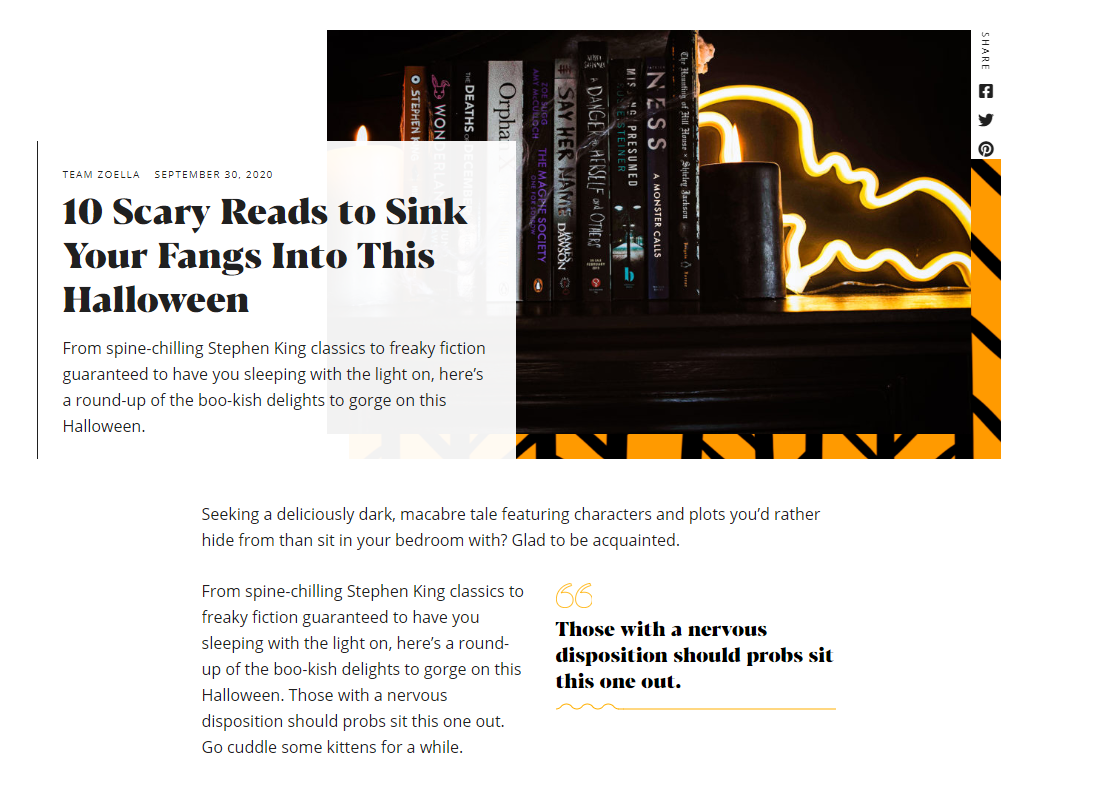

Influencers like Zoella often create a revenue stream by participating in affiliate programs, an “agreement in which a business pays another business or influencer (‘the affiliate’) a commission for sending … sales their way” (Hubspot). There are many different approaches to affiliate marketing, such as comparison-shopping websites, coupon websites, email lists, or reward websites (Authority Hacker 2020). Affiliate marketing differs from influencer marketing in that it is overwhelmingly focused on the Convert stage: Since pay is typically associated with making sales, affiliates aim to convert people to sales. There are, however, affiliate programs that pay per lead (and hence participate in the Act stage) and others that pay per visit (and hence participate in the Reach stage).

Affiliate marketing works as follows: An advertiser, a company that sells a product or a service, offers to pay a third party (e.g., a blogger or a coupon website) to help them promote and sell products and services. The affiliate conducts online activities in order to sell products or services. For example, Figure 5.20 shows a blog post in which Zoella presents her “10 scary reads” for Halloween. Each book is associated with the affiliate program Reward Style. Let’s say a reader reads this blog post, likes the sound of a book, clicks on the link for that book, and purchases it: Zoella will then receive a small percentage of the sale for helping make this sale happen.

You can typically easily identify whether a link is part of an affiliate program or not. For example, for Zoella, the link looks like this: https://rstyle.me/+U7XZh4aYDVf0s7elU5SykA. We can thus see that it is associated with the Reward Style program. Affiliate programs will create different types of links, which typically include the publisher (affiliate) website ID (or PID), the ad id (AID), and the shopper (or visitor) ID (or SID). This allows tracking of sales across publishers, ads, shoppers, and reward affiliates accordingly.

The two main payment structures that exist for affiliates are the following:

- PPS (pay per sale): The advertiser pays the publisher a percentage of the sale that was created by a customer referred by the publisher (revenue sharing model).

- CPA (cost per acquisition/cost per action/cost per lead): The advertiser pays only when an advert delivers an acquisition after the user clicks on the advert. Definitions of acquisitions vary depending on the site and campaign. It may be a user filling in a form, downloading a file or buying a product.

Exercises

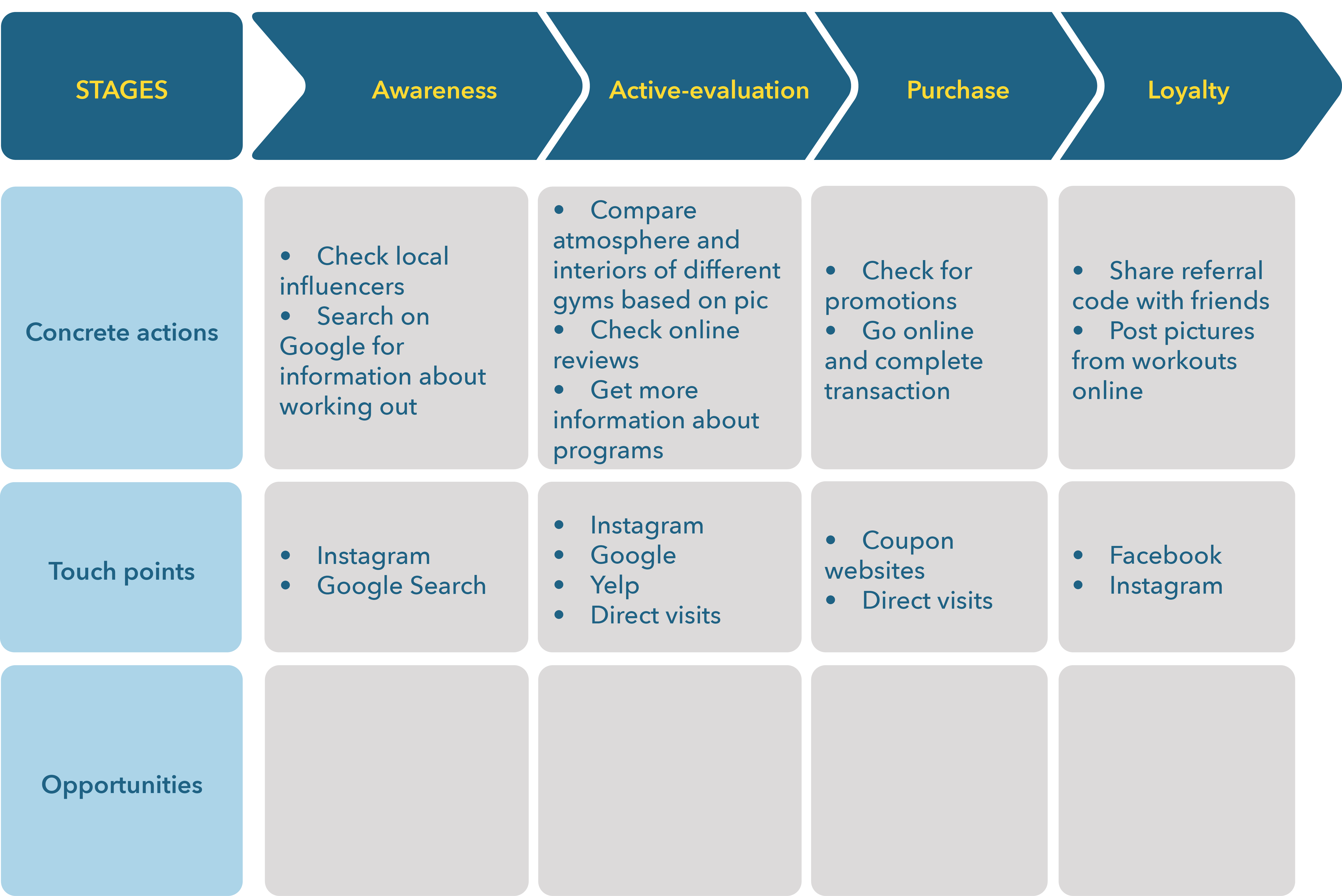

As in the previous chapter’s exercise, you are a fitness center creating a campaign for people who want to get back into shape.

One of the personas you are targeting is Avery.

Avery is a person living in a major Canadian city center. They are their late twenties to early thirties and are in the top 20% in revenue in their city. With increased responsibilities at work and a newborn, Avery had put exercising aside for a few years. They feel sluggish, lack energy, and miss having a stronger connection with their body. With age, their body has also started to transform, and they have started to feel self-conscious about it. To remediate this, they want to get back into exercising weekly. They don’t have much time, and they also don’t know much about working out or the market—for example, where to work out or how to work out.

- First, create a search ad (headline, description, and display URL, with a choice of keywords) for the awareness stage. Use longtail keywords.

- Then, for this ad, sketch a landing page, using the five main elements we covered.

You should be asking yourself the following questions:- What is the objective associated with awareness for consumers? How does this influence my search ad?

- What stage of the RACE framework does awareness align with? What are the objectives for my firm at this stage? How does that influence my landing page design?

- Next, using the ad you created in the first part of this exercise, think of two ways to transform your ad to fit the following social media platforms:

- Identify which type of payment approach (e.g., CPC or CPA) you should go for and provide a reason why.

- Finally, find a couple of influencers on Instagram that could help you with this campaign. Explain how you’d find these influencers and why they are ideal for your campaign, and decide which payment model to adopt to create a campaign with them.