Understanding the Digital Consumer

Pierre-Yann Dolbec

Overview

In this chapter, we discuss how digitalization is transforming the journey of consumers. To better understand how to do marketing online, we also cover basic marketing tools (i.e., persona and consumer journey) to help us create digital marketing campaigns. We conclude the section by discussing journey maps.

Learning Objectives

Understand the concepts of personas, journeys, and maps, how to calculate customer lifetime value, and why it is important.

Understanding Consumers Through Personas

There are two broad approaches to conducting marketing: mass marketing (i.e., an undifferentiated approach where products are simply sold to the masses) or targeted marketing (click here for more information on these approaches). In the latter approach, firms practice segmentation and tailor marketing communications and products to segments. The digital ecosystem makes it quite easy to address segments, even segments of one. Although it is possible to practice mass marketing online, many processes unique to digital marketing, such as web analytics, A/B testing, or the use of online targeting platforms, work best when firms have defined segments. For this reason, we are going to emphasize a targeted approach in this course.

To practice targeted marketing, firms use segmentation to create groups of consumers that are homogeneous (i.e., they have similar characteristics to each other) but are heterogeneous from the rest of the population (i.e., they are differentiated by their shared characteristics).

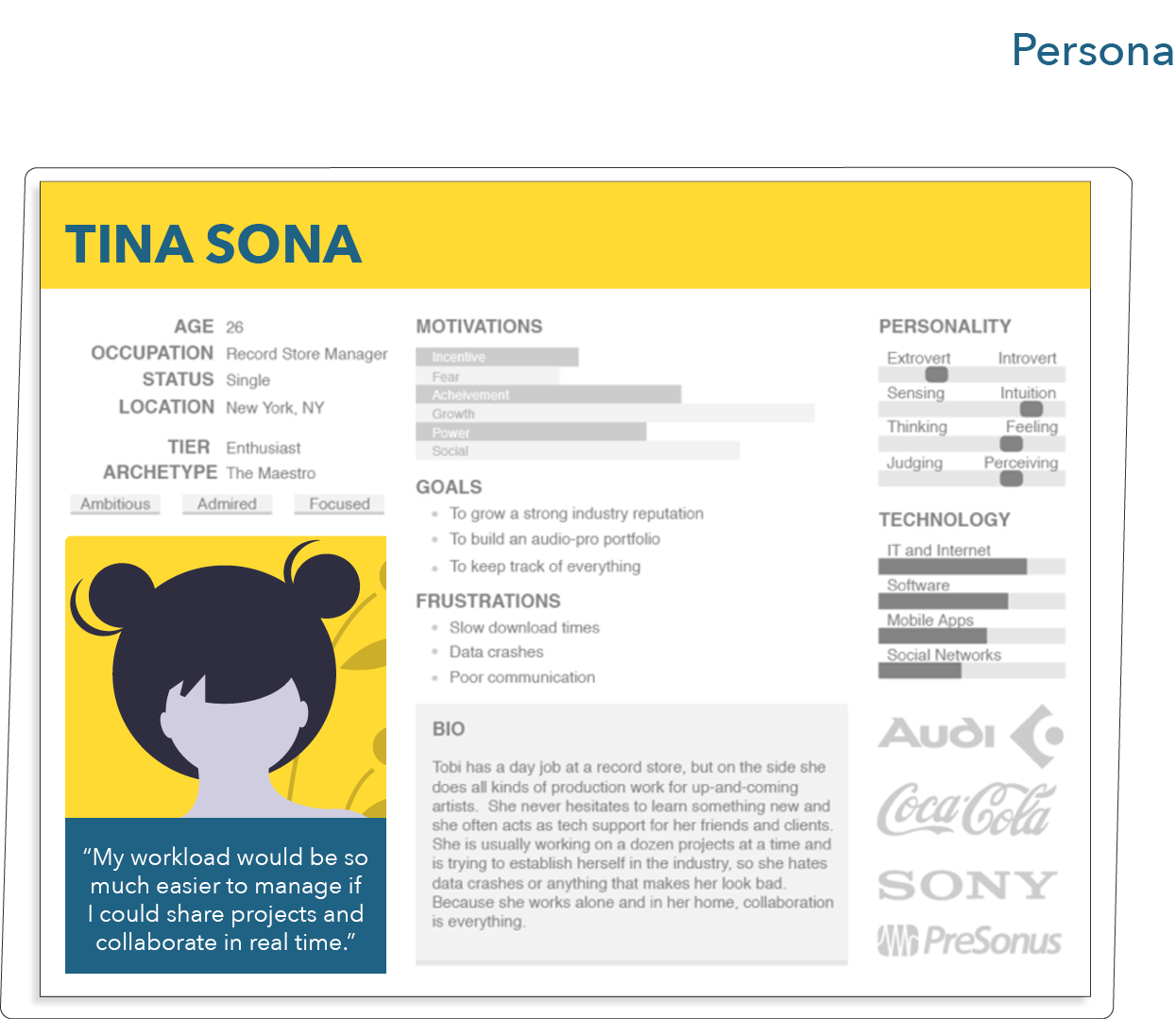

A useful tool to help create and represent segments is personas. Personas are semi-fictional, generalized representations of a customer segment. They help you better understand your customers (and prospective customers) and make it easier for you to tailor content to the specific needs, behaviors, and concerns of different segments.

Personas are important because they help you understand who your ideal consumers are, what their characteristics are, and how to talk to them. The needs, desires, and problems of your personas (or segments more generally) should be the starting point of any marketing strategy. As a reminder from chapter 1, our goal as marketers is to create value, and in digital marketing campaigns, we create value by representing the customer. The only possible way to do so is to understand who this customer is and what they need. Personas can assist in a wide variety of marketing activities, from creating campaigns and ads to guiding product and service development to helping with customer support. We will see how shortly.

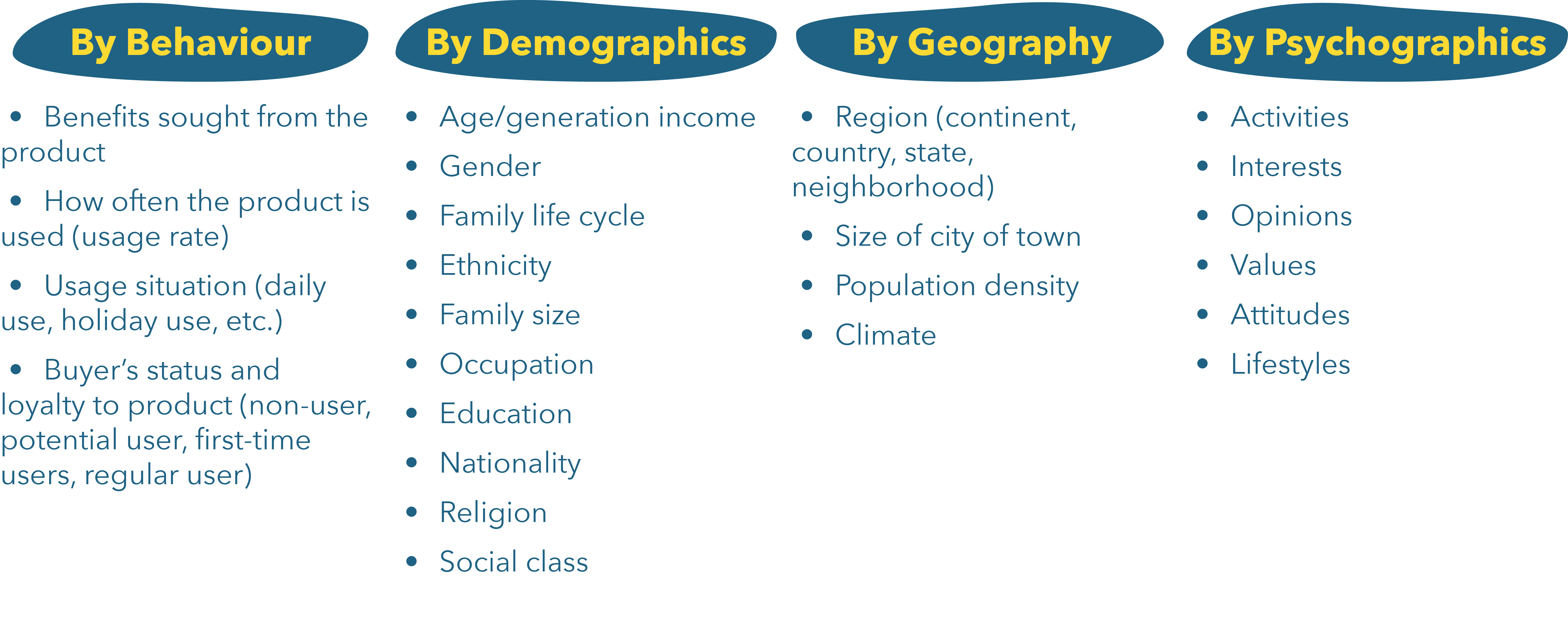

Firms develop personas the same way they develop segments: through market research and the use of internal data. Firms typically segment consumers based on their behaviors (which are also now trackable online!), demographics, lifestyles, or psychographics (see Figure 2.2 for a brief summary or, for a text description of the figure contents, click here).

Segmenting based on these variables is highly useful for informing online targeting strategies. For example, on the Facebook Ads platform, you can easily select to deliver an ad to people aged between 18 and 25 years old living within a kilometer of Mile End who like cycling.

However, these variables are less informative concerning how to talk to these consumers. For this reason, we emphasize the importance of intersecting segments with their goals, wants, needs and motivators and the challenges they face.

In her book Introduction to Consumer Behaviour, Andrea Niosi explains these as follows:

A goal is the cognitive representation of a desired state, or, in other words, our mental idea of how we’d like things to turn out (Fishbach & Ferguson 2007; Kruglanski, 1996). This desired end state of a goal can be clearly defined (e.g., stepping on the surface of Mars), or it can be more abstract and represent a state that is never fully completed (e.g., eating healthy). Underlying all of these goals, though, is motivation, or the psychological driving force that enables action in the pursuit of that goal (Lewin, 1935).

Motivation can stem from two places. First, it can come from the benefits associated with the process of pursuing a goal (intrinsic motivation). For example, you might be driven by the desire to have a fulfilling experience while working on your Mars mission. Second, motivation can also come from the benefits associated with achieving a goal (extrinsic motivation), such as the fame and fortune that come with being the first person on Mars (Deci & Ryan, 1985). One easy way to consider intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is through the eyes of a student. Does the student work hard on assignments because the act of learning is pleasing (intrinsic motivation)? Or does the student work hard to get good grades, which will help land a good job (extrinsic motivation)?

Consumer behavior can be thought of as the combination of efforts and results related to the consumer’s need to solve problems. Consumer problem solving is triggered by the identification of some unmet need. A family consumes all of the milk in the house; or the tires on the family car wear out; or the bowling team is planning an end-of-the-season picnic: these present consumers with a problem which must be solved. Problems can be viewed in terms of two types of needs: physical (such as a need for food) or psychological (for example, the need to be accepted by others).

Although the difference is a subtle one, there is some benefit in distinguishing between needs and wants. A need is a basic deficiency given a particular essential item. You need food, water, air, security, and so forth. A want is placing certain personal criteria as to how that need must be fulfilled. Therefore, when we are hungry, we often have a specific food item in mind. Consequently, a teenager will lament to a frustrated parent that there is nothing to eat, standing in front of a full refrigerator.

Most of marketing is in the want-fulfilling business, not the need-fulfilling business. Apple does not want you to buy just any watch; they want you to want to buy an Apple Watch. Likewise, Ralph Lauren wants you to want Polo when you shop for clothes. On the other hand, a non-profit such as the American Cancer Association would like you to feel a need for a check-up and does not care about which doctor you go to. In the end, however, marketing is mostly interested in creating and satisfying wants.

Often discussion around needs will separate them into those which are utilitarian (practical and useful in nature) and hedonic (luxurious or desirable in nature).

To this list, we add the notion of challenges, by which we mean an obstacle faced by a consumer in resolving a need or fulfilling a want. This is important because consumers turn to the internet every day to help them answer challenges they face in their everyday lives, whether it is how to change a tire, how to have the perfect Friday night makeup, or how to paint a room. Resolving challenges drives the consumption of online content.

Hence, when creating a persona, you create a semi-fictional representation of a segment by bringing together the following information:

- Basic behavioral, demographic, geographic, and psychographic information to facilitate targeting

- Needs and/or wants and/or goals and/or challenges to facilitate the creation of your campaign

- Information that makes your persona feel real, such as

- a picture

- a quote from an interview with a real consumer

- a name

- examples of “real” problems

Take the example of RV Betty (Figure 2.3, text here).

Can you find the information mentioned above in this short persona?

Rethinking the Consumer Journey

A consumer journey is the trajectory of experiences through which a consumer goes: from not knowing they want something, to buying this something, to performing post-purchase activities (the most obvious being consuming the product). Put more theoretically, the consumer journey is “an iterative process through which the consumer begins to consider alternatives to satisfy a want or a need, evaluates and chooses among them, and then engages in consumption” (Hamilton et al. 2019). The journey is composed of pre-purchase activities, that is, activities consumers engage in prior to buying a product; purchase activities, or what people do to acquire a product; and post-purchase activities, or what consumers do once they have bought a product (Lemon and Verhoef 2016).

As a side note, we make a distinction in this course between customer journey, which would focus on the journey of a customer with a specific firm and would include, for example, touchpoints solely associated with that firm, and consumer journey, which is a broader perspective on consumers who “undertake [a journey] in pursuit of large and small life goals and in response to various opportunities, obstacles, and challenges” (Hamilton and Price 2019, p. 187). By touchpoint, I mean “any way a consumer can interact with a business, whether it be person-to-person, through a website, an app or any form of communication” (Wikipedia).

Understanding the consumer journey is important because doing so strongly contributes to firm performance. For example, a survey by the Association of National Advertisers in 2015 found that top performers in a market understood the journey better than their peers and had better processes to capture journey-related insights and use them in their marketing efforts (McKinsey 2015).

The journey varies greatly depending on which market a firm evolves in. It also varies depending on personas and their specific goals. For example, a survey by Google found that some markets, such as banking, voting, and finding a credit card, will typically have a longer journey than others, such as groceries or personal care products. Variation also exists within markets. For example. Google found three types of journeys for restaurants: one where consumers pick a restaurant within the hour, one where consumers pick a restaurant a day before going, and a last one where consumers pick restaurants two to three months before going.

Can you think of what these relate to?

We can hypothesize: If you’re at work and looking for a place to have lunch, chances are, you won’t dedicate much time to it and will pick a restaurant within the hour before going. If you are going out with friends or a Tinder date, you might be a bit more involved in the process and pick the restaurant one or two days before. Lastly, if you are going to travel (and are a foodie!) or you want to make a marriage proposal, this will require more planning, and you might start your journey much, much earlier. This also has implications for restaurants! Some restaurants who cater to downtown lunchers might be better off pushing Instagram ads with the menu of the day, or some daily sale, around 11 a.m. or just before lunch. Restaurants catering to groups or dates might want to start campaigns on Wednesdays to capture Friday and Saturday restaurant-goers. And restaurants that target the marriage proposal or foodie crowds might need longer, “always-on” continuous marketing activities to bring in patrons.

Understanding Consumer Journeys

Our understanding of consumer journeys has greatly evolved over the last two decades, and there exist a number of ways to conceptualize journeys. It is important to understand that these are not perfect representations of reality. Rather, they are thinking tools that help us create marketing campaigns. In real life, people tend not to be so linear in their decisions.

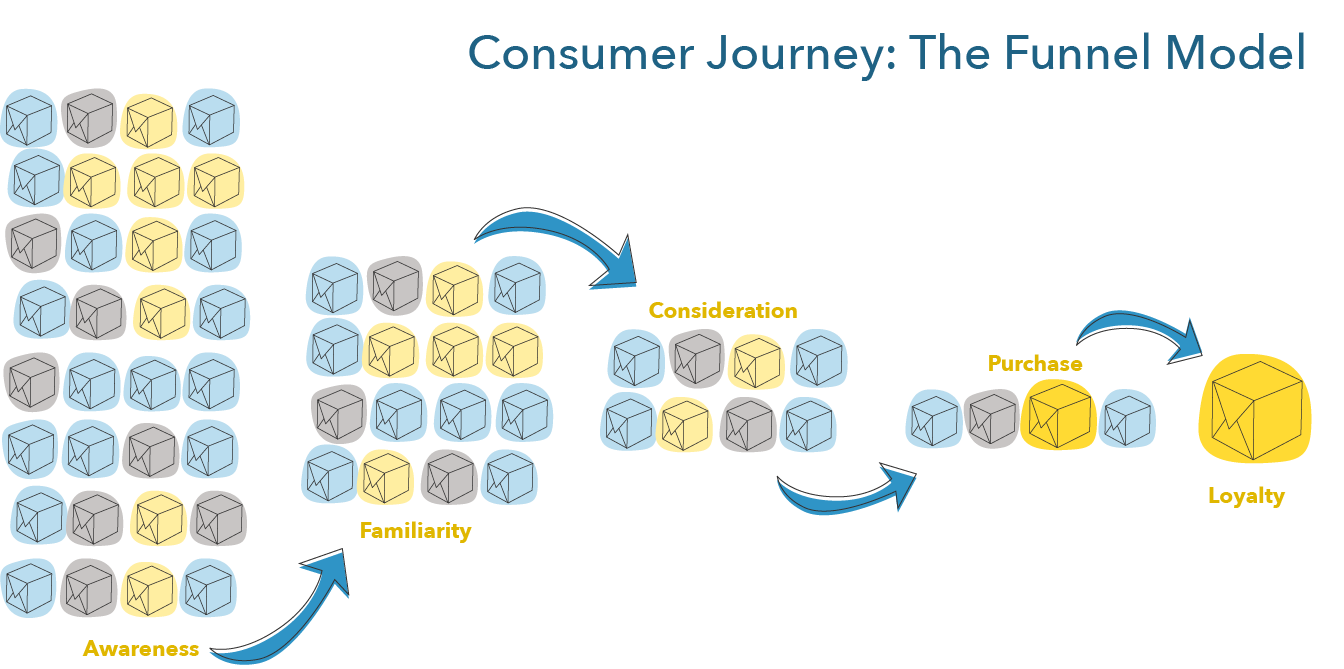

A common conceptualization found in marketing textbooks is one where consumers move between different stages, initially being aware of a large number of brands and then slowly refining their understanding of the options in the market to make their purchase. McKinsey represents such a typical model here (Figure 2.4). In this model, the consumer goes through five stages:

- Awareness: the consumer is aware of a large number of products or brands in the market that might help address their need.

- Familiarity: From this large number of brands or products they are aware of, the consumer will perform some initial research and become familiar with a subset of brands.

- Consideration: From this smaller number of familiar brands, the consumer will continue their research efforts, eliminate some brands that do not fit their criteria, and narrow their list to a smaller number of considered brands (i.e., a “consideration set”).

- Purchase: Once ready to buy, the consumer might try out a product or seek in-depth information on an even smaller subset based on their consideration set, from which they will purchase a product or choose a brand.

- Loyalty: Assuming their consumption experience goes well, the consumer may become loyal to the product or the brand.

This understanding of the journey is based on a funnel model, where consumers start by being aware of a large number of brands and, over time, reduce their options as they go through each of the stages. This has a number of implications for marketers.

A first central assumption is that, to ultimately be chosen by consumers, companies need to make sure that consumers are aware of them. This partly helps explain the prevalence of mass marketing: it serves to create awareness.

A second central assumption is that consumers start with a large set of brands that they are aware of and reduce this set over time to a smaller and smaller set of brands as they search for and evaluate options.

McKinsey introduced in 2009 a competing model for the consumer journey, based on the purchase decisions of close to 20,000 consumers across five industries. They found that these two assumptions did not hold: First, consumers do not start with a large set of brands they are aware of. Second, consumers do not reduce their options as they go through the stages of the funnel. Rather, the number of options they consider increases throughout their journey.

If you think of some recent purchases you made, this makes sense. Let’s say I want a pair of running shoes. I might be aware of some brands and models, probably the ones that do the most mass advertising: Nike, Adidas, Reebok. Then, I turn to the internet to perform some searches. I’ll use general key terms like “what running shoes should a beginner get” or “reviews for running shoes 2020.” Through my search efforts, I will encounter new brands I had not considered originally, for example, Asics, Brooks, and Saucony.

In this example, rather than following the funnel metaphor, where the set of brands I was aware of reduced to a smaller set of familiar brands and an even smaller set of considered brands, I added brands to my consideration set.

This has important implications for digital marketers: First, traditional, push, mass marketing media activities are not necessary. Second, as consumers do research, they broaden the set of products or brands they consider. We will see how this has led to the rapid growth of inbound marketing activities that help consumers with their problems and help consumers evaluate their options. This is because brands now understand that by supporting consumers throughout their journey, they can enter consumers’ consideration set and ultimately make a sale.

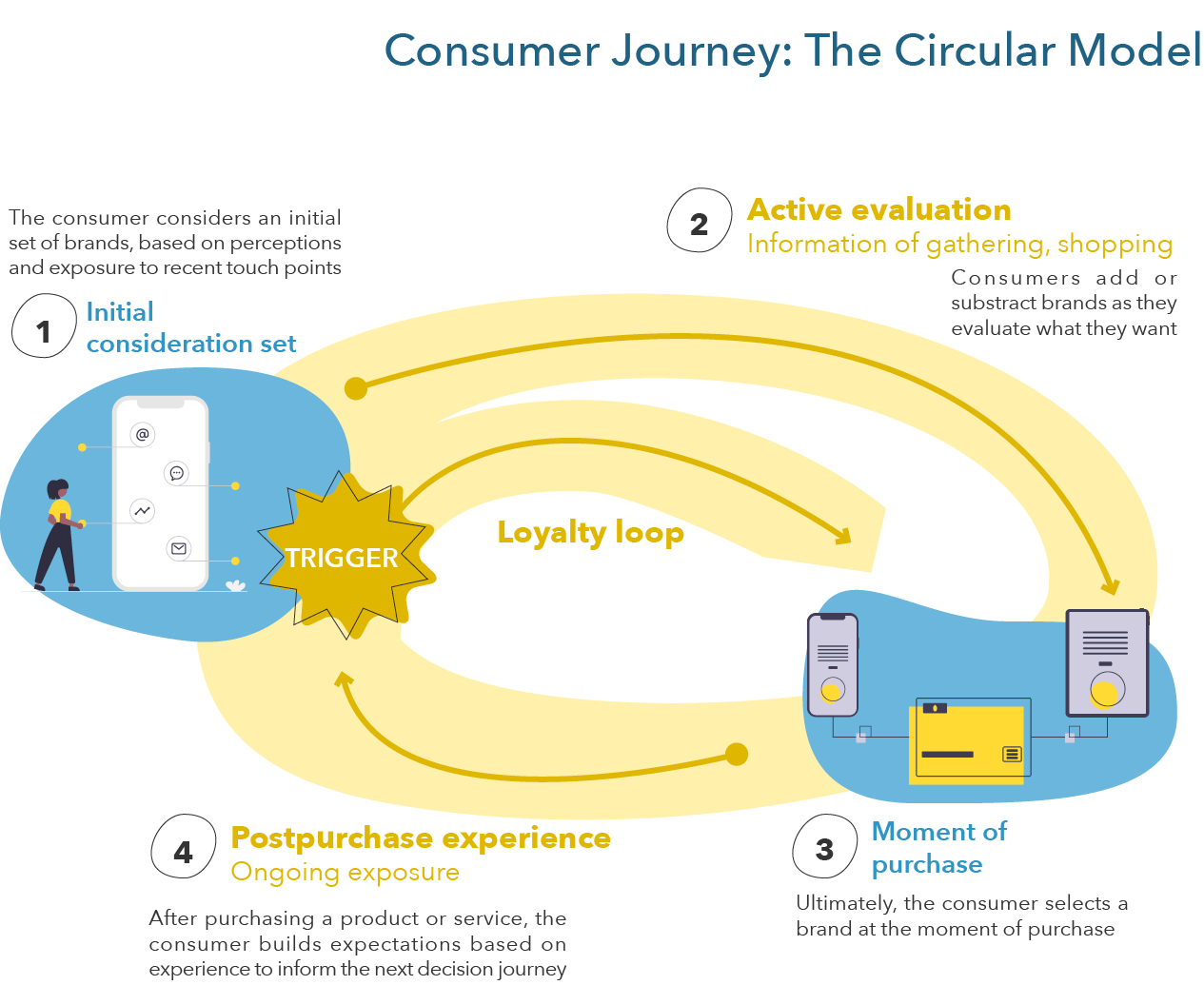

McKinsey thus proposes a competing model, a circular model for the consumer journey. The model is circular because consumers enter a loyalty loop where they cycle between using a product or brand, buying this product or brand again, participating in post-purchase activities, and so on. The McKinsey model has the following stages (also depicted in Figure 2.5):

- Trigger: The consumer experiences a need, a problem, or wants to achieve a goal, which initiates their journey

- Initial consideration set: The consumer considers an initial set of brands based on their experiences, brand perceptions, and exposure to recent touchpoints. For the initial consideration set, the most influential touchpoint is company-driven marketing, such as advertising, direct marketing, sponsorship, and the like. See a graphic representation here.

- Active evaluation: This is a new stage introduced by McKinsey. At this stage, the consumer actively evaluates their options through information gathering and shopping. Often, consumers will do their information gathering online. It is at this stage that consumers add brands to their consideration set. We are not in a funnel model anymore. This is the first difference important to digital marketers: It means we can enter consumers’ consideration set without having to conduct awareness-generating campaigns. If we help consumers make their decisions, or if we have reviews online, for example, we can be considered by them. McKinsey finds that the most influential touchpoint for this stage is consumer-driven marketing, such as word of mouth, the information found during online searches, and reviews.

- Moment of purchase: The consumer selects a brand and make a purchase.

- Post-purchase experience: After purchasing a product or a service, the consumer builds expectations based on their experience. This will inform the loyalty loop. A second important difference from the funnel journey happens at this stage: Consumers start creating content for brands (i.e., the “consumer-driven marketing” efforts I refer to in stage ‘3’). Think about products or services you bought recently: Maybe you posted a picture about it on Instagram, maybe you wrote a review on Yelp!, or maybe you participated in some company-supported marketing activities.

These two important revisions to the journey—the expansion of the consideration set during active evaluation and the importance of consumers participating in consumer-driven marketing at the post-purchase stage—open up many content-based possibilities for digital marketers. As we’ve discussed, our goal in digital marketing is to represent the customer: What are their needs? Goals? Problems? How can we support them in addressing these? Our objectives are not to sell products or talk about our brand. Rather, we will see that we make sales online by supporting consumers throughout their journey—helping them understand their problem, helping them evaluate solutions, helping them better understand our product.

Zero Moment of Truth

In an example of great content marketing for themselves (i.e., this concept helps sell Google products!), Google introduced in 2011 the concept of zero moment of truth (ZMOT), “a new decision-making moment that takes place a hundred million times a day on mobile phones, laptops, and wired devices of all kinds … that moment when you grab your laptop, mobile phone, or some other wired device and start learning about a product or service (or potential boyfriend) you’re thinking about trying or buying.” It turns out to be quite a useful concept to think about how consumers make purchases in the digital era.

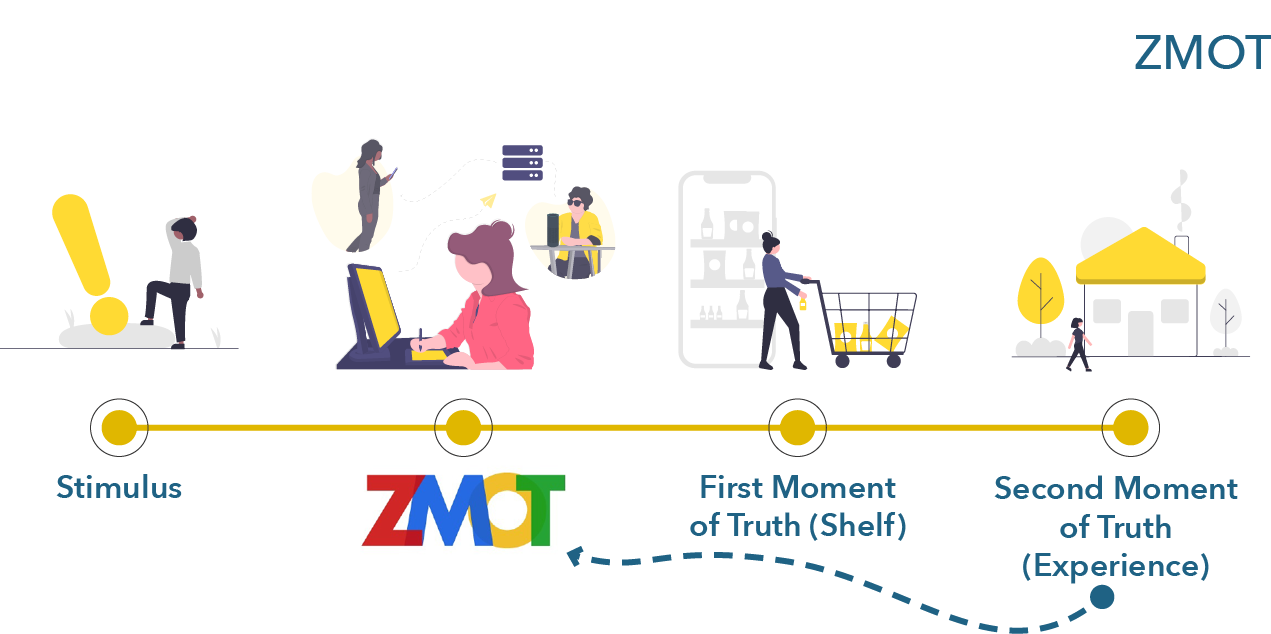

A moment of truth is a contact with a brand or a product during which a consumer forms an impression (Carlzon 1989). To understand the ZMOT, it is important to contextualize it historically. Why is it called the “zero” moment of truth? Quite simply, prior to Google introducing this concept, there were already two moments of truth (Figure 2.6):

- First moment of truth: When a shopper notices a product in a shopping environment which influences their buying decision.

- Second moment of truth: When a consumer experiences a product following their purchase decision.

The ZMOT is the moment of truth—the context between a consumer and a brand—that happens prior to a shopper noticing a product in a shopping environment. Concretely, ZMOT “moments” could appear while

- performing online searches,

- talking with family and friends,

- comparison shopping,

- seeking information from a brand,

- reading product reviews,

- reading comments online, or

- starting to follow a brand.

In contrast, the first moments of truth happen while

- looking at a product on a shelf,

- reading a brochure at the store,

- talking to a salesperson,

- looking at a store display,

- talking with a customer service representative, or

- using a sample in-store.

According to Google, the essential characteristics of ZMOTs are that they happen online, when the consumer is in charge (and this relates to inbound marketing), and during multiway conversations. To capitalize on ZMOTs, Google recommends being present in moments that matter. By this, the marketing juggernaut means that you should have content and ads that respond to the needs, problems, and goals that consumers are typing in the form of search queries in a search engine. All of this requires, as you might have guessed by now, a deep understanding of your consumers and their journeys.

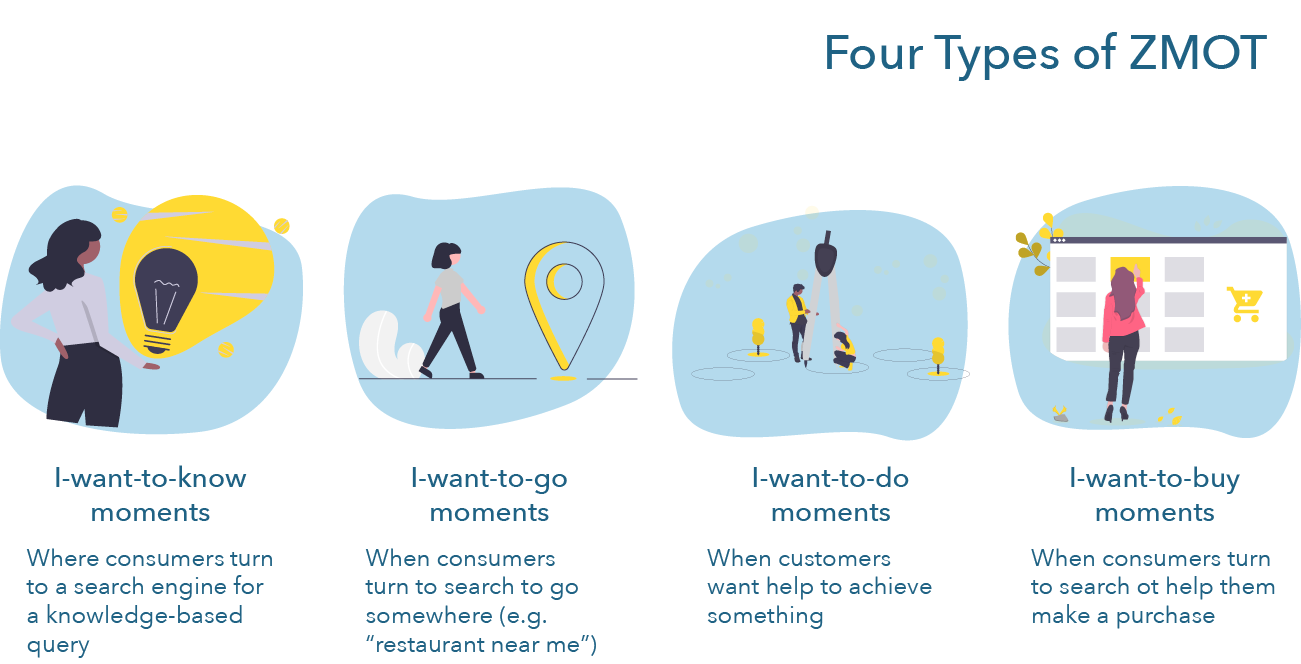

Google identifies four ZMOTs and briefly explain how these interact with journeys here. The four types, also shown in Figure 2.7, are the following:

- I-want-to-know moments, where consumers turn to a search engine for a knowledge-based query

- I-want-to-go moments, when consumers turn to search to go somewhere (e.g., “restaurant near me”)

- I-want-to-do moments, when consumers want help to achieve something (Fun fact! For a while there, the most searched ‘how-to’ video was ‘how to kiss.’ Now, isn’t that sweet!)

- I-want-to-buy moments, when consumers turn to search to help them make a purchase

These are important conceptual tools. They represent opportunities for companies online to create content. These are not simply ways to understand how consumers use search engines and interact online. Rather, they are tools to help us create better content. What kind of content would you create for these four different ZMOTs?

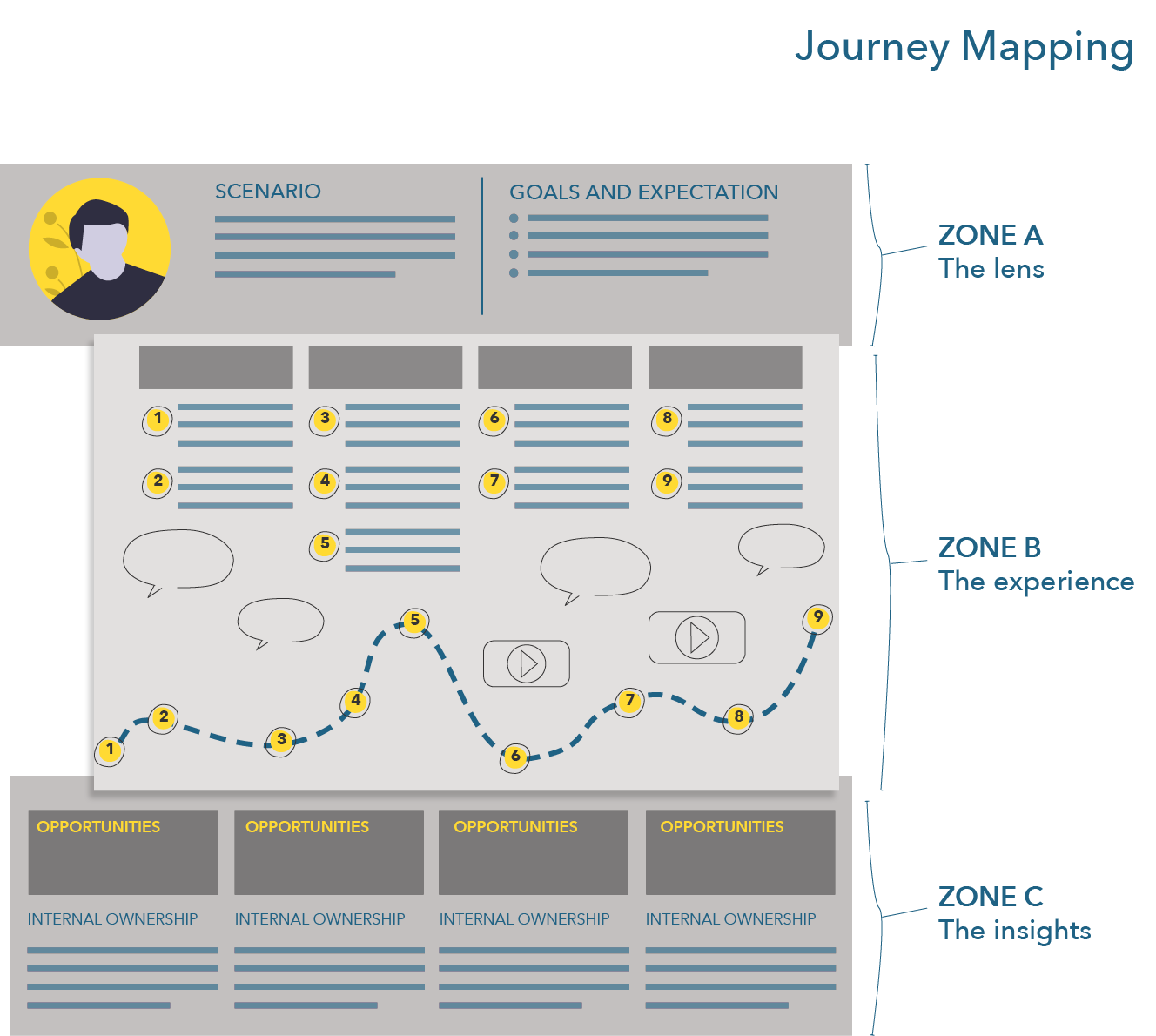

Journey Mapping

Now that we have the vocabulary for these concepts, it’s time to turn our attention to using them in practice. The journeys and ZMOTs are generic ways to understand how consumers go about buying products. Knowing how consumers conceptually move from a trigger to making a purchase to becoming loyal to a brand or product might be interesting in itself, but it is much more useful if we can actually use this in real-life campaigns. Effective strategies demand a tailored understanding. We cannot stay at a conceptual level. We need to translate them to real-life experiences. To do so, we can perform journey mapping.

A journey map is a visual representation of the journey of a consumer. It brings together the conceptual tools we have seen in this chapter: persona, consumer journey, and moments of truth. Journey maps vary based on segments/personas. Each persona represents a different consumer segment. These segments will go about buying products differently. Think about, for example, how you go about buying products and how your parents go about buying products.

Journey maps exist in a wide range of shapes and forms. They all, however, share some common elements:

- the persona

- conceptual stages from a journey (e.g., trigger, active evaluation, purchase, and post-purchase; or awareness, consideration, purchase, and loyalty)

- concrete actions consumers take at each of these stages

- touchpoints that they encounter (in this course, I strongly encourage you to include yours and those of others, i.e., this is a consumer journey, you should be thinking more broadly than only your firm)

- opportunities associated with the aforementioned actions

This page presents a clear example of this kind of journey template.

Journey maps are useful. They help you understand how consumers move through their journeys to address their needs and problems. Each action they take represents an opportunity for your brand to create a connection with a consumer. A clear understanding of the concrete steps that consumers take to buy products should be the starting point of the creation of your marketing campaigns. What do consumers do at the awareness stage? How can your brand support their actions? Do consumers search for specific things? What about at the active evaluation stage? In the next chapter, we examine how firms can position websites on specific searches. This will help create a bridge between what consumers are doing online and how we can answer their search queries.

Exercises

How to Use a Persona

Let’s take as an example the following persona, “RV Betty”:

Betty lives in a suburb of a city. Her husband is also retired. They have been talking about traveling in an RV upon retirement for years—this is a long-time dream of theirs. The kids are self-sufficient and have been out of the house for long enough that Betty doesn’t have to worry. She’s been retired just long enough to be bored. While she doesn’t consider herself wealthy, she and her husband have substantial savings and are prepared to enjoy their retirement.

Betty is worried about the logistics of traveling in an RV—how easy will it be to find utility hookups, where are the best places to stay if you have one, etc. She also wants something comfortable; she plans on spending a lot of time in it. She has other retired friends, so she wants additional sleeping space, and she wants to make sure they have plenty of room for food and even cooking. She wants as much ease as possible when traveling.

Based on this persona, briefly sketch three pieces of content. More precisely, concentrate on the general idea of what this piece of content would be about and draft the following:

- a first piece that addresses a problem or a need she is facing

- a second piece that helps her evaluate her options

- a last piece that sells your product

Creating a Persona

Sketch up a persona for a Montreal real estate company specializing in first-time house buyers. To do so,

- identify a few sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age and revenue), and

- find one general need or problem they are facing.

Tip: Ask yourself why these people would need a house. For example, you might ask yourself the following questions:

- Why would people move to a house in Montreal?

- Are there different groups of first-time house buyers? What differentiates them? Which one are you concentrating on?

- Is there one need or problem that unites that group?

Moving From Persona to Journey Map

- Sketch a journey map for your real estate persona using the following journey stages:

- awareness

- consideration

- purchase

- post-purchase

- Identify two concrete activities that your persona is engaging in for each stage

- Identify two touchpoints that your persona is coming into contact with for each stage

- Identify one opportunity for your company per activity