Chapter Five

THE MODERN PORTRAIT

in Photography and

Impressionist Painting

CONTENTS

Introduction

5.1

5.2

Early Photographic Portraiture

5.3

Portrait Photography, Art, and Aesthetics

5.4

Félix Nadar: Beyond the Documentary Portrait

5.5

Julia Margaret Cameron: Art Photography and Pictorialism

5.6

Modern Impressionist Portrait Paintings and the Impact of Photographic Techniques

5.7

Edgar Degas and the Influence of Photography

5.8

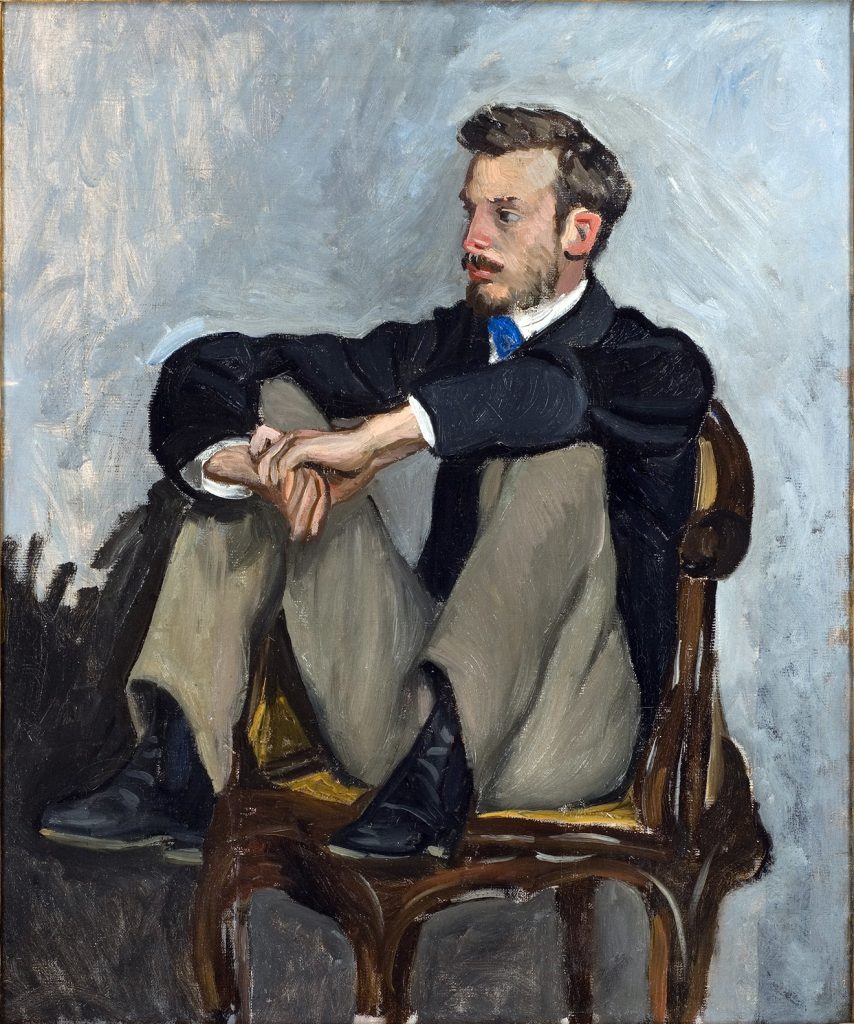

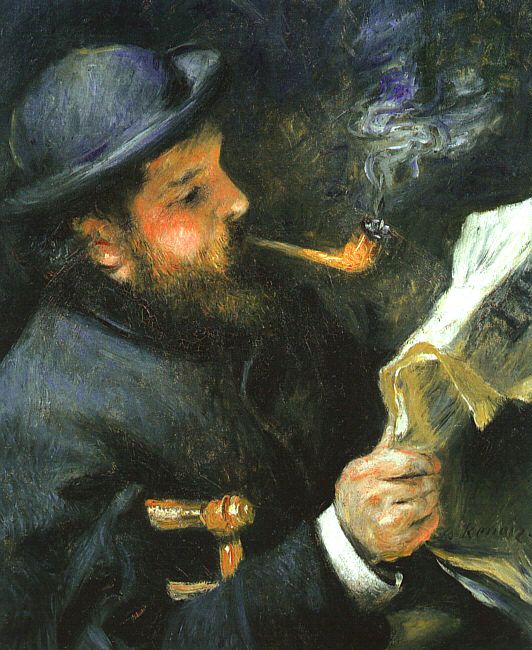

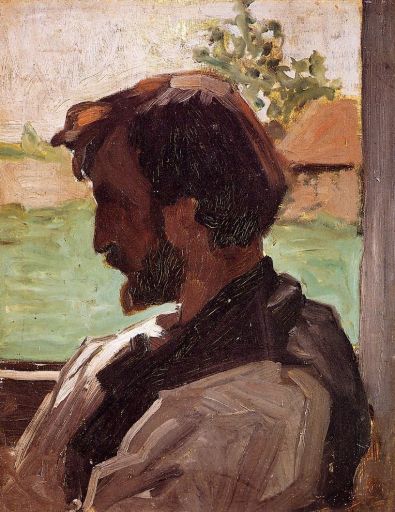

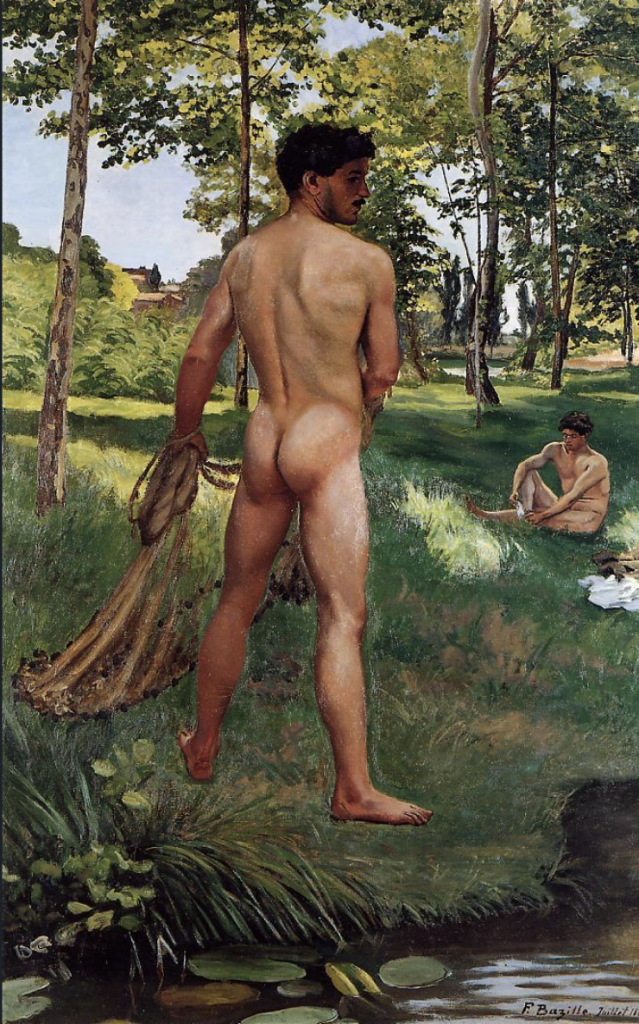

Impressionist Portraits of Colleagues and Friends

5.9

5.10

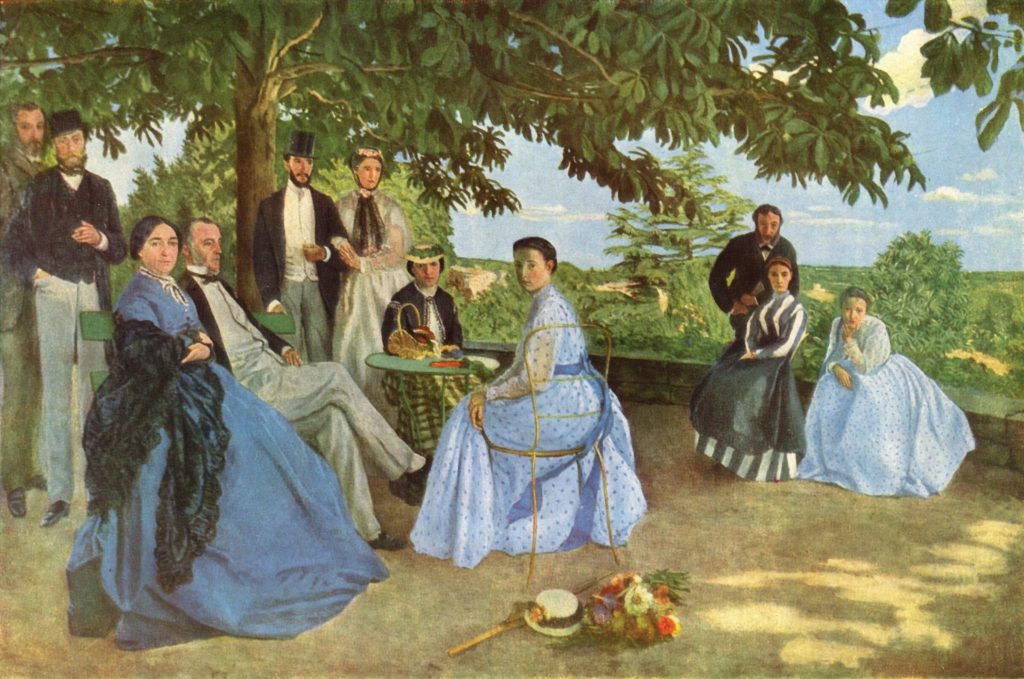

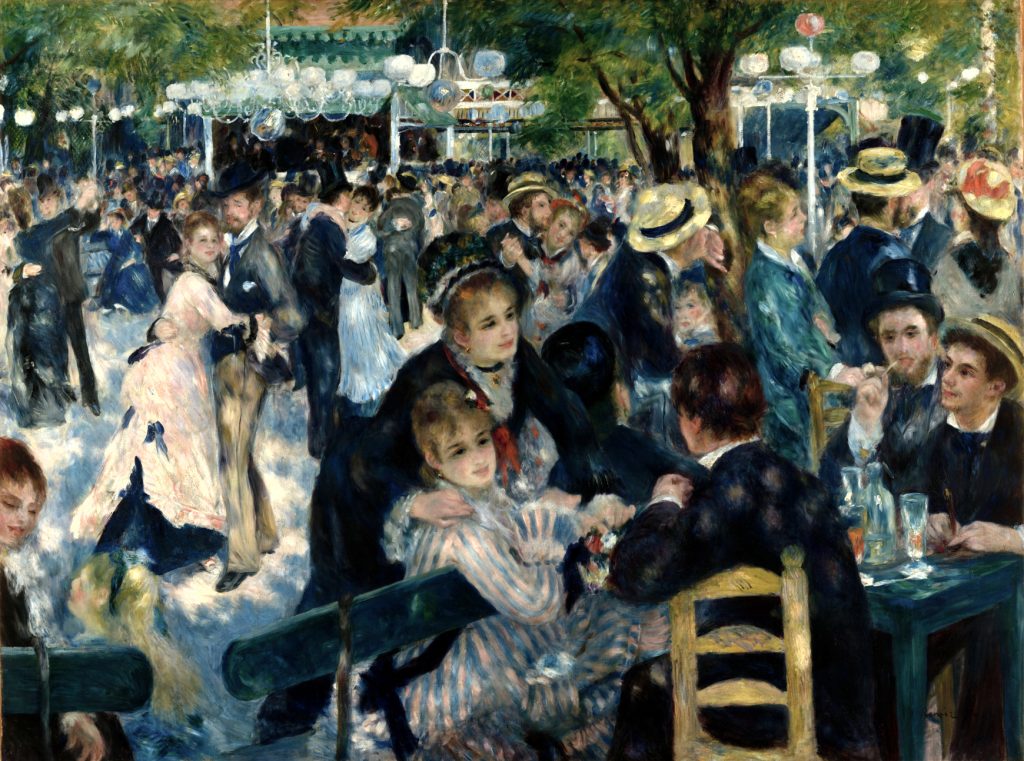

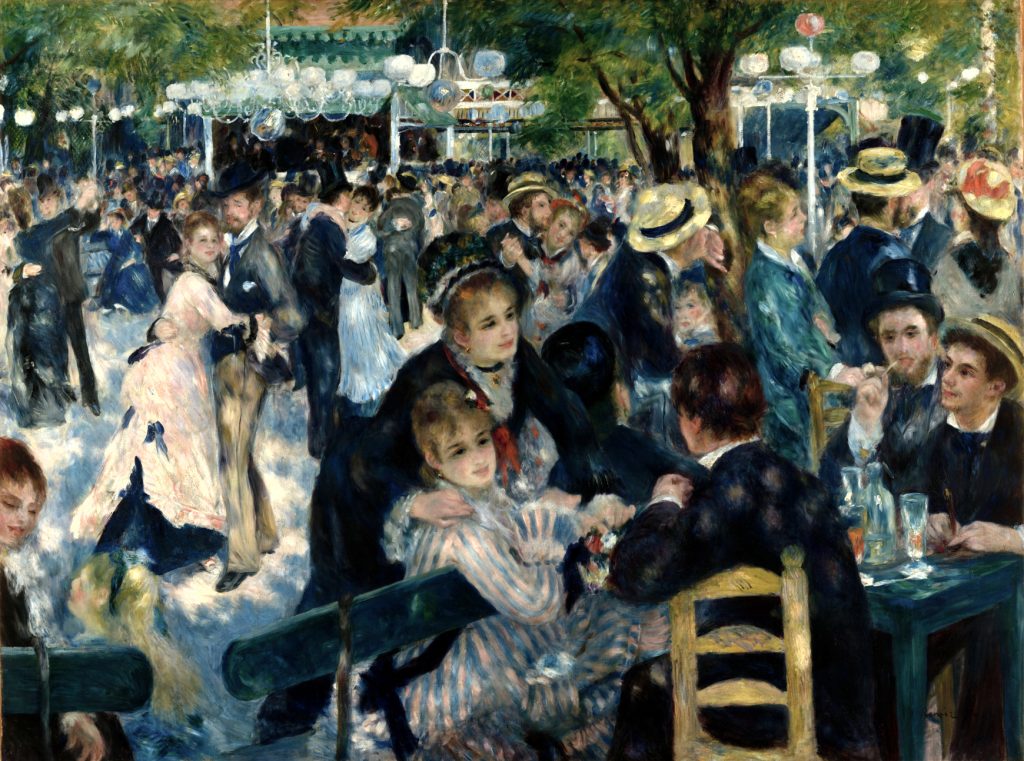

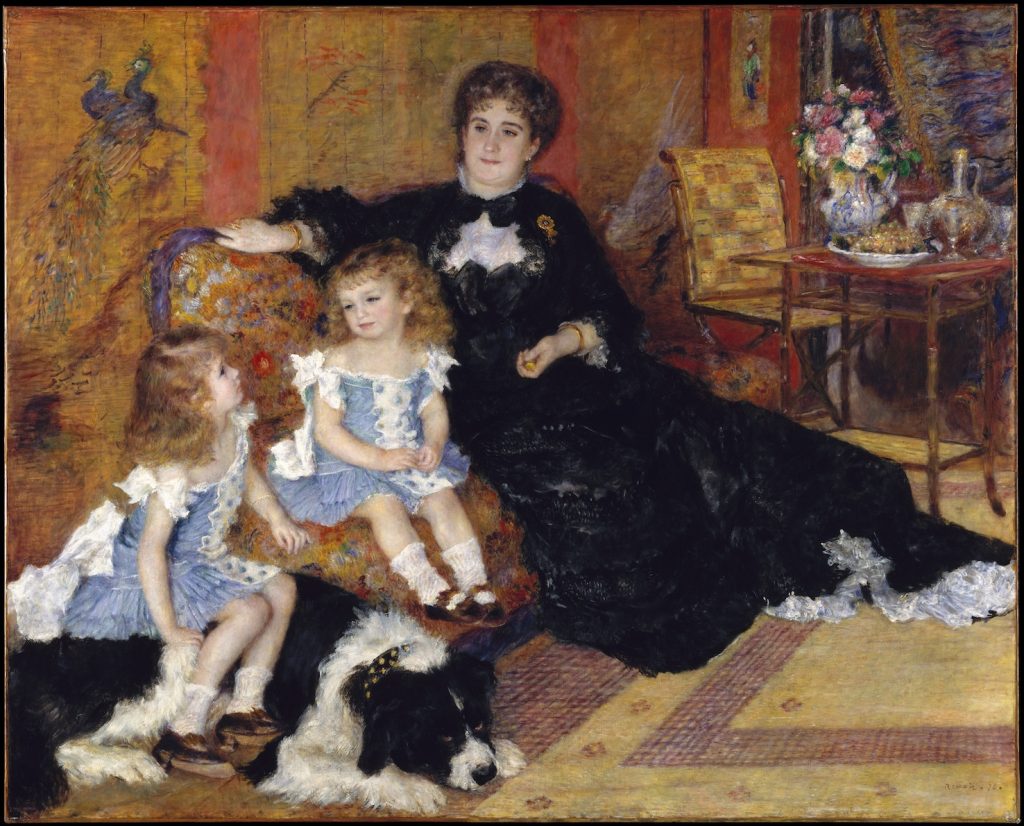

Auguste-Pierre Renoir and the Group Portrait

5.11

INTRODUCTION

The invention of photography significantly impacted avant-garde painters who were interested in representing contemporary life. The immediacy and objectivity of the medium attracted Impressionists whose interest was in capturing the ever-changing, everyday experiences of the modern world. The advent of photography radically altered how visual art was both conceived and perceived.

Freed from the burden of mimetic representation, artists shifted their attention to the portrayal of the fleeting and fragmentary events of life. Painters slowly began to appropriate the techno-formal aspects of the still photograph—the shaping power of light, the use of altered perspective, an interest in cropped spaces, and the exploration of increased spatial ambiguities that echoed the moving continuum of lived experience—to paint their images of a world in flux. Initially, paintings that strayed too far from objective representation were deemed unfinished, but in time their arbitrariness became accepted as an aspect of modern art.

The relationship between photography and painting was reciprocal. The photographic portrait did not remain static but evolved as well, moving from a mechanistic recording of likeness with the one-of-a-kind invention of the daguerreotype to the popular multiples of the carte-de-visite to more sophisticated and nuanced studio photography and finally to pictorialism, which engaged with broader art forms as art photography and secured its legitimate place as fine art.

This chapter will consider Impressionist portraiture within its historical context and its relationship to the parallel evolution of photographic images. The work of artists associated with the French avant-garde, such as Degas, Bazille, and Renoir, will be considered in terms of the innovations they implemented within the context of the portrait genre and how their ambitions for painting people in a modern world advanced the conceptualization and creation of late nineteenth-century portraiture.

5.1

| The Invention of Photography

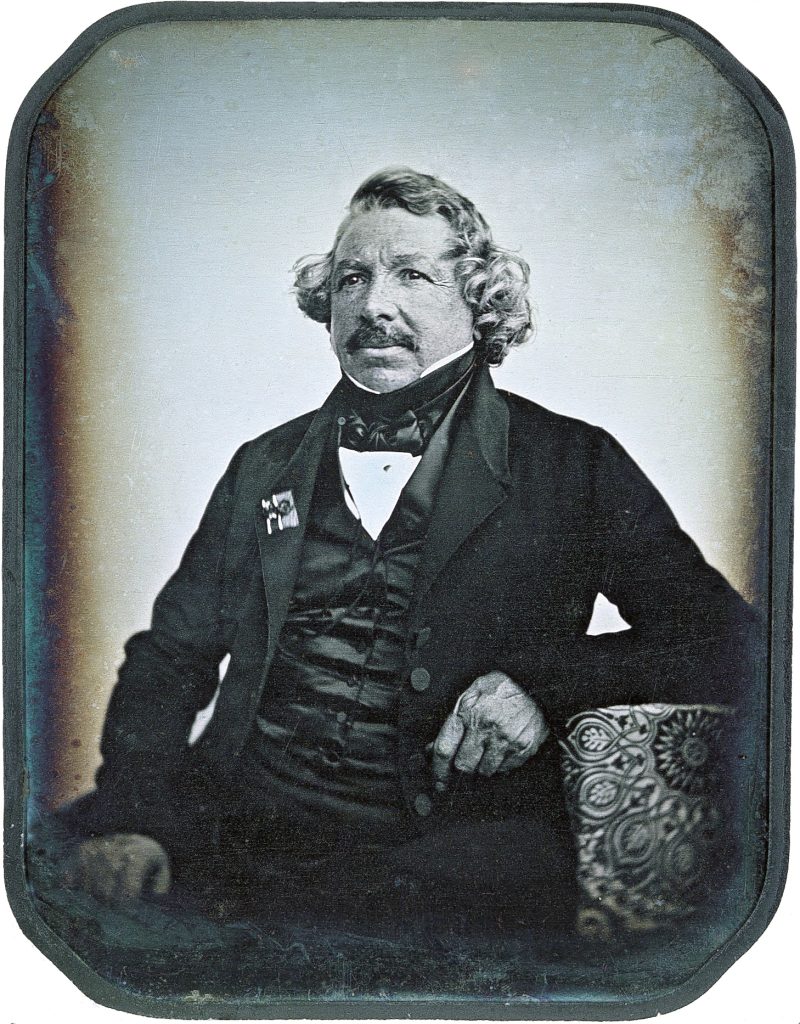

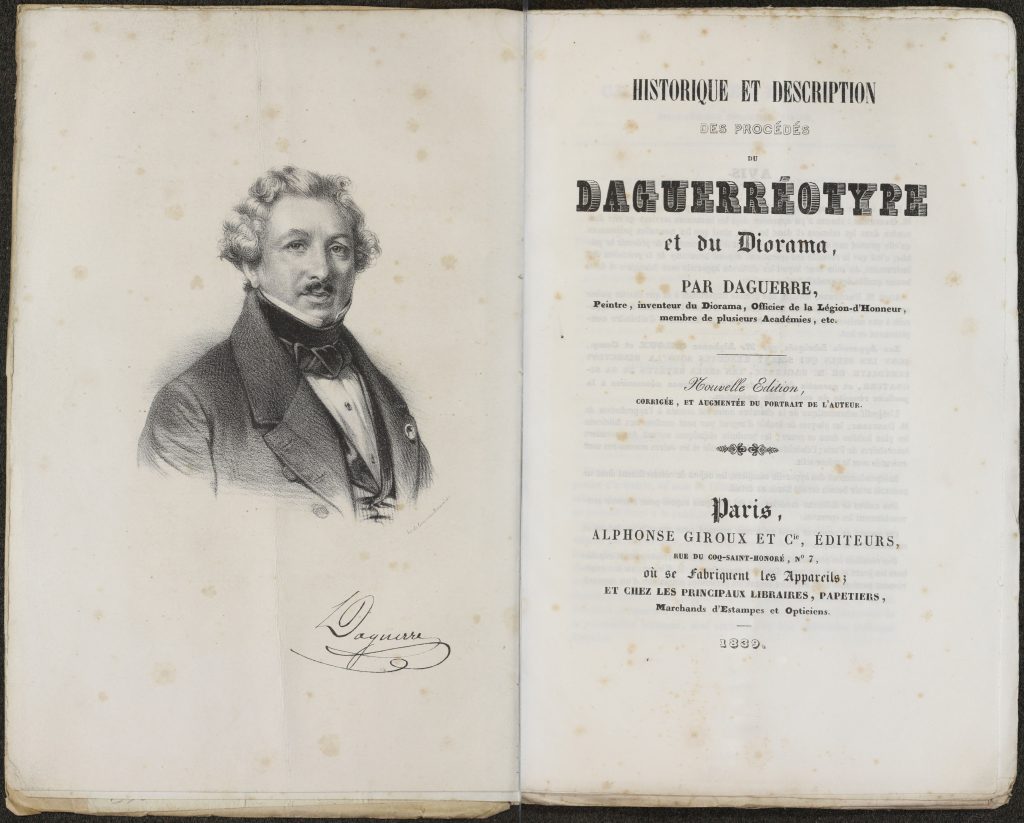

In 1837, Louis Daguerre, a painter, printmaker and proprietor of the Parisian Diorama, invented the daguerreotype camera. It was the first commercially available method of mechanical image reproduction. Each daguerreotype was a finely detailed and permanent unique image recorded on a silvered copper plate. The process involved treating the silver-plated sheets with iodine to make them light sensitive, then developing them in a camera with mercury vapour.

The invention of photography in the early nineteenth century revolutionized the nature and possibilities of visual representation.

Daguerre introduced his product to the French Académie des Sciences in January 1839, and to the public in late summer of that year. He followed up by patenting his product, demonstrating the process at the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, and publishing an informational handbook. He also actively promoted his invention in Berlin, New York, and London.

Daguerreotypes initially required long exposure lengths due to the low light sensitivity of the plates. By 1841, better plates combined with Joseph Petzval’s development of a new lens in Vienna (the Petzel lens) shortened exposure times sufficiently to open the door to large-scale portrait photography.

Before the invention of photography, a painted portrait was an unaffordable luxury for the average person. Even in its infancy as a relatively precious commodity, the daguerreotype made a photo portrait accessible and highly desirable. As the technology improved, so did the cost, boosting popularity and demand. In 1849 alone, approximately 100,000 photographic portrait pictures were recorded in Paris, adversely affecting miniature portraitists and negatively impacting larger portrait commissions.

Daguerreotypes were positive, inverted images that could not be produced as multiples. Images could, however, be reproduced through “redaguerreotyping” the original plate. As a technique, it required a subject to sit still for a light-dependent period of time, anywhere from three to thirty minutes.

The innovations made by Fox Talbot, who invented the negative-positive photographic process, and the physicist Louis Fizeau, who developed Gilding, a gold-toned image, made it possible to produce photographs more resistant to deterioration and cheaper to make.

5.2

| Early Photographic Portraiture

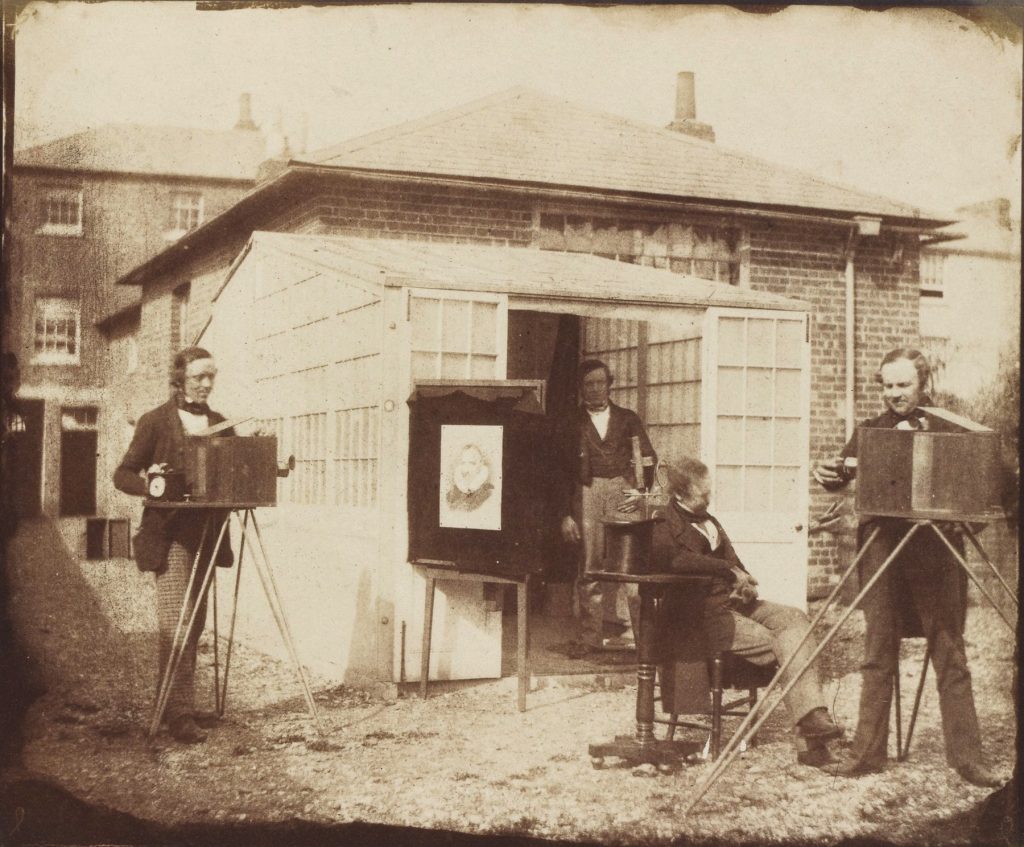

From its early beginnings, photography presented as a double-edged medium, both a scientific device and a means of aesthetic expression. The first generation of portrait photographers struggled with this duality even as they experimented with new techniques, debating whether photography should appropriate the aesthetic concerns and characteristics of portrait painting, the expressive significance of poses and background props, and issues of composition, lighting and how to render tone and texture monochromatically.

Malcolm Daniel provides an overview of photographers’ challenges in “The Industrialization of French Photography after 1860” (Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004. (http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/infp/hd_infp.htm)

The decade of the 1850s was a “golden age” in the art of photography. Artists of great vision and skill took up a fully mature medium, tackled ambitious subjects, and lavished care in producing large, richly toned, and colorful prints for a select group of fellow artists or wealthy patrons. By the 1860s, times were changing, and the medium became increasingly industrialized. Instead of mixing chemicals according to personal recipes and hand coating their papers, photographers could buy commercially prepared albumen papers and other supplies. Increasingly, the marketplace pressured photographers to produce a greater quantity of cheaper prints for a less discerning audience. In marketing to a middle class, aesthetic factors such as careful composition, optimal lighting conditions, and exquisite printing became less important than the recognizable rendering of a familiar sight or famous person.

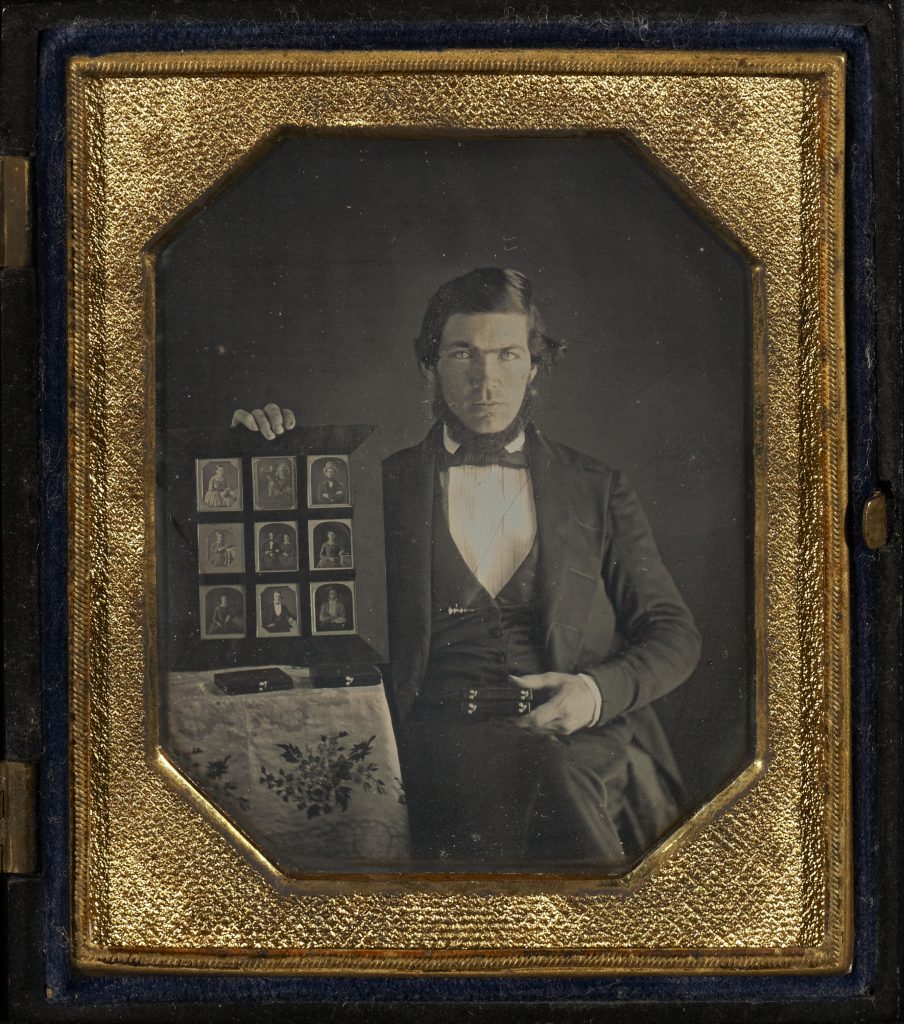

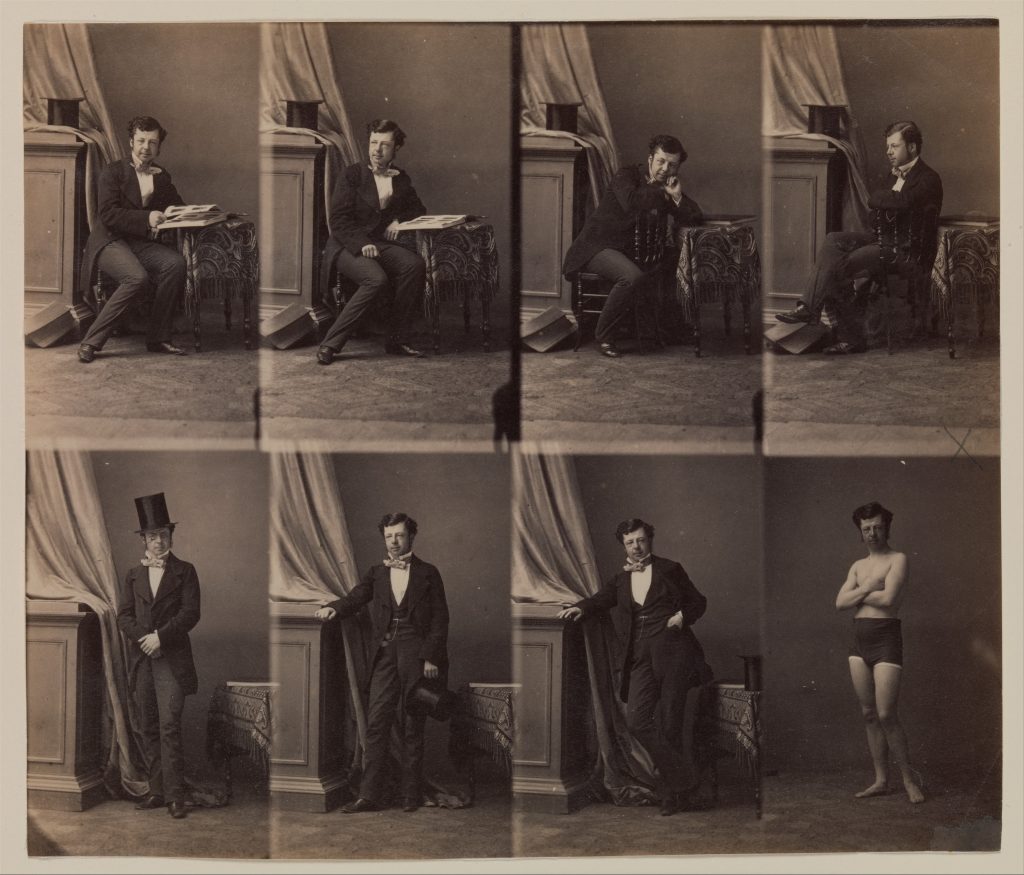

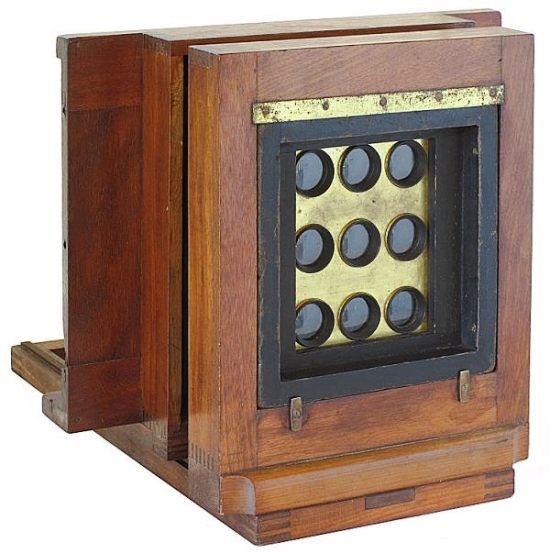

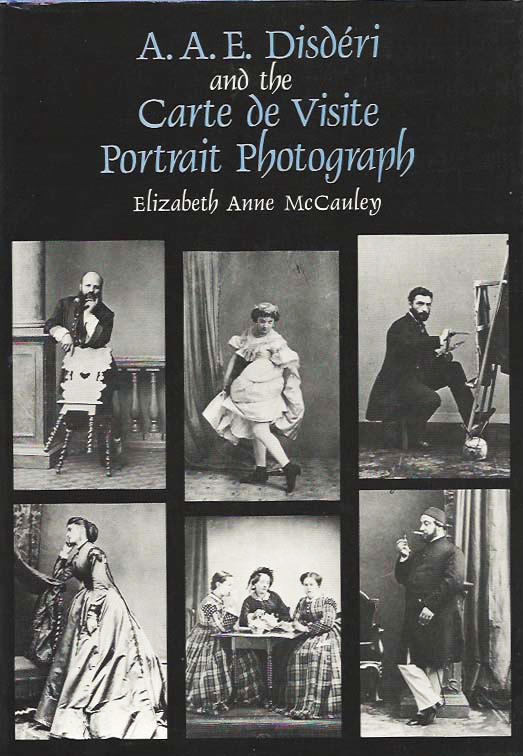

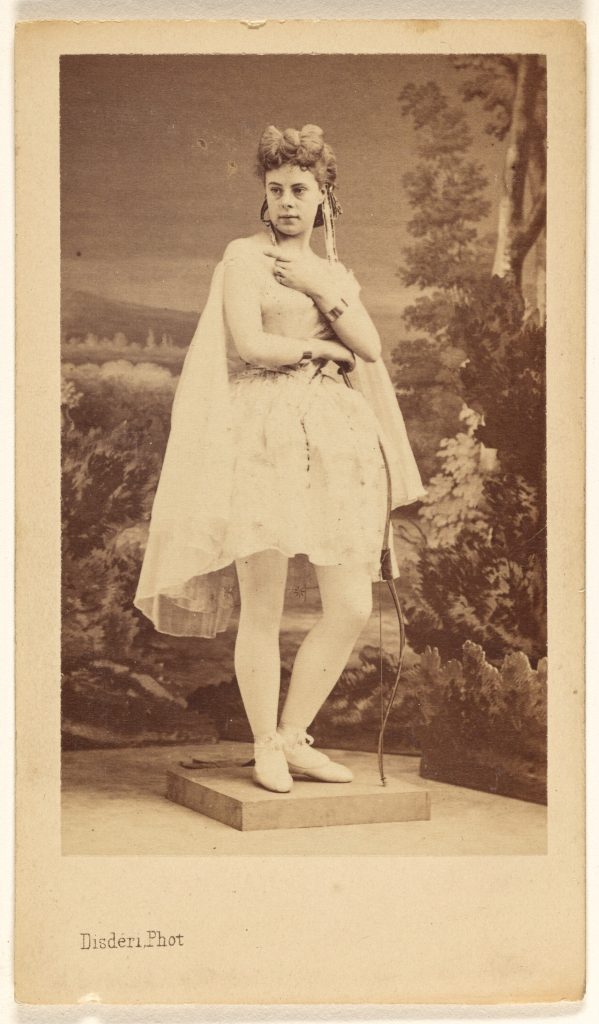

With the industrialization of the photographic medium in the 1860s, pressure turned to production. In 1854, A.A-E. Disdéri had discovered how to produce multiple exposures on a single glass-plate negative which he printed and divided into separate pictures measuring nine-by-six centimetres. The negative could be printed a dozen times cheaply, and just like that, the carte-de-visite (calling card) was born.

Cartes-de-visite (abbreviated CdV) were postcard-size portraits made by a new multiple-lens camera with consecutively releasable shutters. The camera furnished six or eight exposures on a single plate. These multiple images became extremely popular; they were pasted on mounts and distributed to friends and business associates as visiting cards. The CdV craze necessitated hiring teams of new employees (1855 records indicate Disdéri’s business hired as many as 77 assistants), and sales volumes soared.

Early photography precipitated the downfall of miniature painting and presented portrait painters with serious competition. “In the summer of 1861,” according to Helmut and Alison Gernsheim in The History of Photography from the Earliest Use of the Camera Obscura in the Eleventh Century up to 1914 (London: Oxford University Press, 1955), “33,000 people made their living from the production of photographs and photographic materials in Paris alone.”

As Max Kozloff describes in “Nadar and the Republic of the Mind” (Artforum 15 no. 1 (September 1976): 28-39), Disdéri was appointed the first official court photographer:

The royals had found a novel way of coining their images and of putting to use a new technology whose economic success originated in the cachet of their patronage… At the same time, it became clear that an intimate form of social exchange and personal talisman had had a public impetus and played a propaganda role. Ruling families could mime the domestic virtues in cheap, easily distributed images. Bourgeois could have themselves portrayed by means of an aristocratic emblem.

CdV’s were available to everyone, from the wealthy elite to the filles de joie of the Second Empire’s demimonde. They anticipated the democratization of photography with the medium’s second wave of technological innovation with the American George Eastman’s Kodak camera in the 1880s.

Elizabeth Anne McCauley, in A. A. E. Disdéri and the Carte de Visite Portrait Photograph (Yale University Press, 1985), in her analysis of several technical manuals published by Disdéri, describes the criteria he recommended for creating an aesthetic portrait. He advised putting subjects at ease and paying attention to the personality behind the features. “One must be able to deduce who the subject is,” he wrote, “to deduce spontaneously his character, his intimate life, his habits; the photographer must do more than photographe, he must biographe.“

In discussing the origins of the CdV’s mass appeal, McCauley suggests that it occurred after the aristocracy’s first portraits were made, catching on with the general public, who then imitated upper-class dress and demeanour.

As the infatuation with photographs increased, elegant albums were introduced as picture-keepers. This was a fashion that McCauley calls the “elevation of the photographic album to the status of an icon.”

McCauley emphasizes the correlation between the carte-de-visite and the period’s “insidious transformation of the individual into a malleable commodity.” The demand for calling cards was an “early step toward the simplification of complex personalities into immediately graspable and choreographed performers whose faces rather than actions win elections and whose makeup rather than morals gains public approbation.”

The consensus outside the ranks of professional photographers was that photography was not a bonafide art form. In his “The Salon of 1859: The Modern Public and Photography,” Charles Baudelaire decried the rise of the photographic industry and its assumed similarity to art:

During this lamentable period a new industry arose which contributed not a little to confirm stupidity in its faith and to ruin whatever might remain of the divine in the French mind….The idolatrous mob demanded an ideal worthy of itself and appropriate to its nature- that is perfecting understood….Thus an industry that could give us a result identical to Nature would be the absolute of art. A revengeful God has given ear to the prayers of the multitude. Daguerre was his Messiah. And now the faithful says to himself: Since Photography gives us every guarantee of exactitude that we could desire (they really believe that, the mad fools!), then Photography and Art are the same thing.

Despite widespread criticism, photographers increasingly asserted their claim to artistic status, not least of which as a bid to increase their social standing.

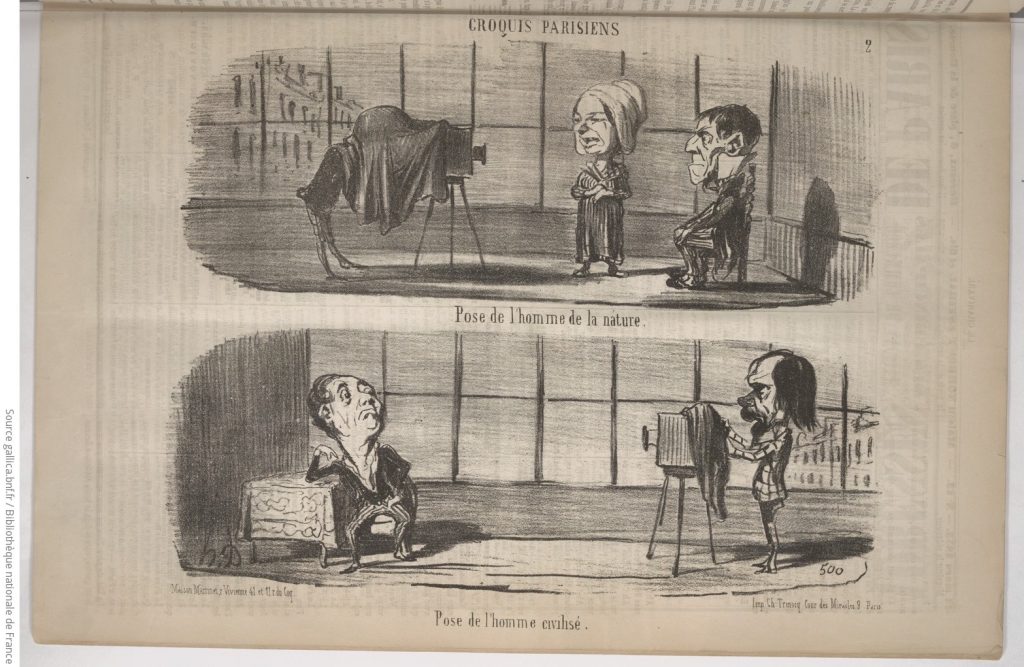

The overwhelming popularity and restrictions of early portrait images led to standardized studio poses and the inclusion of steadying, sometimes overly theatrical, props.

Daumier’s Croquis Parisiens mocked the most typical poses of sitters: the basic frontal rigid orientation of figures looking directly at the camera as if hypnotized, and the artistic photographs characterized by mannered posturing. Daumier labelled them the “pose of the natural man” and the “pose of the civilized man.”

Disdéri’s background in theatrical acting allowed him to pose his subjects more convincingly. His portrait photographs of actors and dancers considerably increased his reputation as an artist.

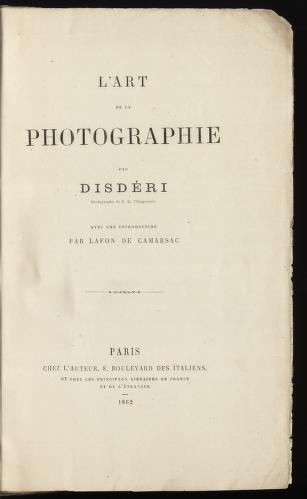

Disdéri’s treatise L’Art de la photographie, published in 1862, offered a wealth of advice on posing the subject. Rather than introducing new declarations about the medium, Disdéri wanted to show that photographic portraiture, like the well-accepted academic portraits shown at the Salon, strove for compositional integrity.

Disdéri insisted that his carte-de-visite photographs respect the formal specifications of the portrait genre, particularly the portrait artist’s ability to capture “a single dominant interest” and the well-defined character or expression of the sitter. He recognized that

a portrait ought to convey a sense of duration rather than the impression of a fragmented moment…It is appropriate to remember that one is trying to reproduce not a scene, but a portrait, and one must not abandon the search for intimate and profound resemblance in order to chase after some aspect that might present itself but that is not a fundamental part of the subject…What needs to be found is the characteristic pose, that which expresses not this or that moment but all moments, the complete individual. (English translation from the chapter titled “The Photograph Pose” in Dianne W. Pitman Bazille: Purity, Pose and Painting in the 1860s (Pennsylvania University Press, 1998), 108-9).

5.3

| Portrait Photography, Art, and Aesthetics

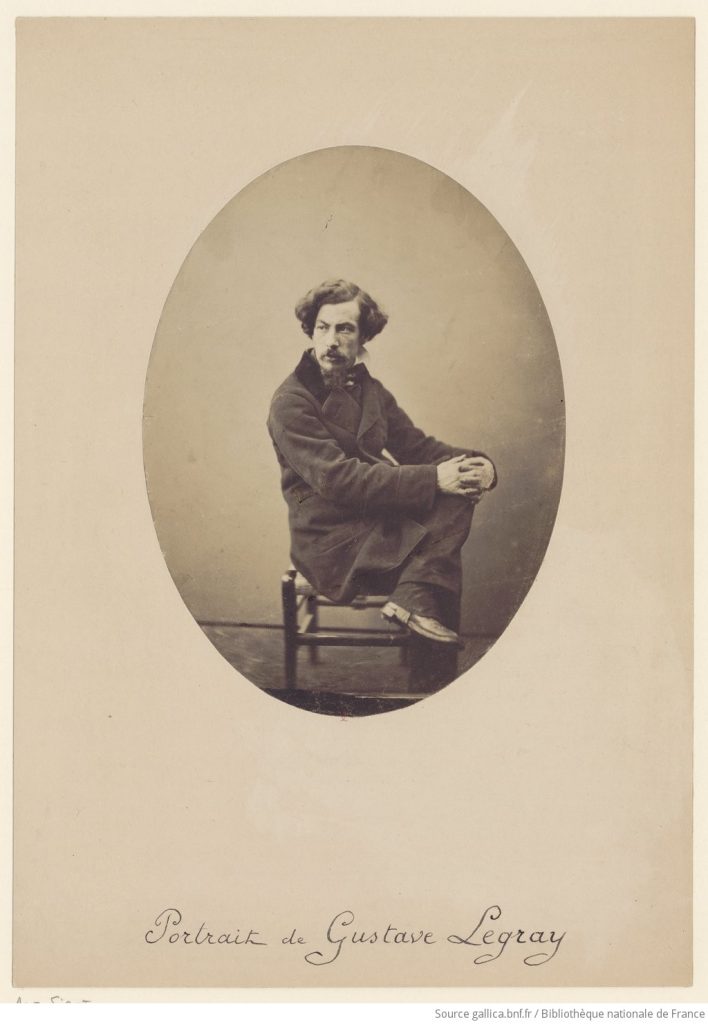

Gustave Le Gray was a central figure in French photography of the 1850s. Malcolm Daniel elaborates on the artist’s contributions to the field of photography in “Gustave Le Gray (1820–1884).” (Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/gray/hd_gray.htm (October 2004)

Born the only child of a haberdasher in 1820 in the outskirts of Paris, Le Gray studied painting in the studio of Paul Delaroche, and made his first daguerreotypes by at least 1847. His real contributions—artistically and technically—however, came in the realm of paper photography, in which he first experimented in 1848. The first of his four treatises, published in 1850, boldly, and correctly, asserted that “the entire future of photography is on paper.” In that volume, Le Gray outlined a variation of William Henry Fox Talbot’s process calling for the paper negatives to be waxed prior to sensitization, thereby yielding a crisper image.

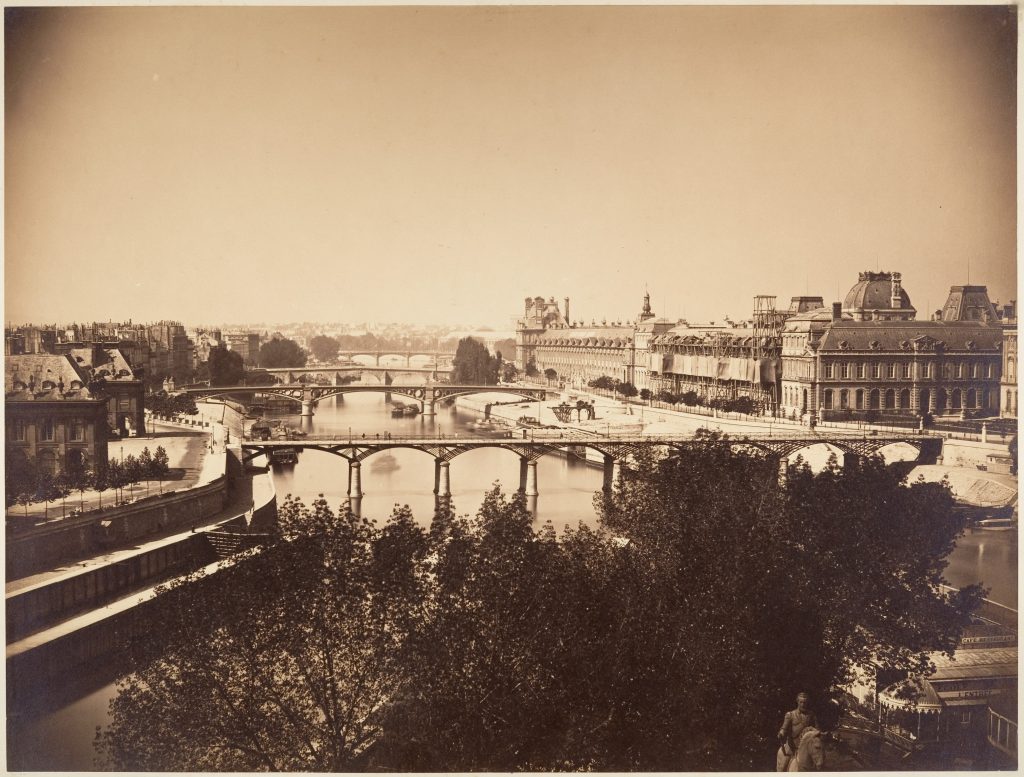

By the time Le Gray was assigned a Mission Héliographique by the French government in 1851, he had already established his reputation with portraits,

views of Fontainebleau Forest,

and Paris scenes.

Le Gray’s mission took him to the southwest of France, beginning with the châteaux of the Loire Valley, continuing with churches on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela and eventually to the medieval city of Carcassonne just prior to “restoration” of its thirteenth-century fortifications by Viollet-le-Duc.

In the 1852 edition of his treatise, Le Gray wrote: “It is my deepest wish that photography, instead of falling within the domain of industry, of commerce, will be included among the arts. That is its sole, true place, and it is in that direction that I shall always endeavor to guide it. It is up to the men devoted to its advancement to set this idea firmly in their minds.” To that end, he established a studio, gave instruction in photography (fifty of Le Gray’s students are known, including major figures such as Charles Nègre, Henri Le Secq, Émile Pécarrère, Olympe Aguado, Nadar, Adrien Tournachon, and Maxime Du Camp), and provided printing services for negatives by other photographers.

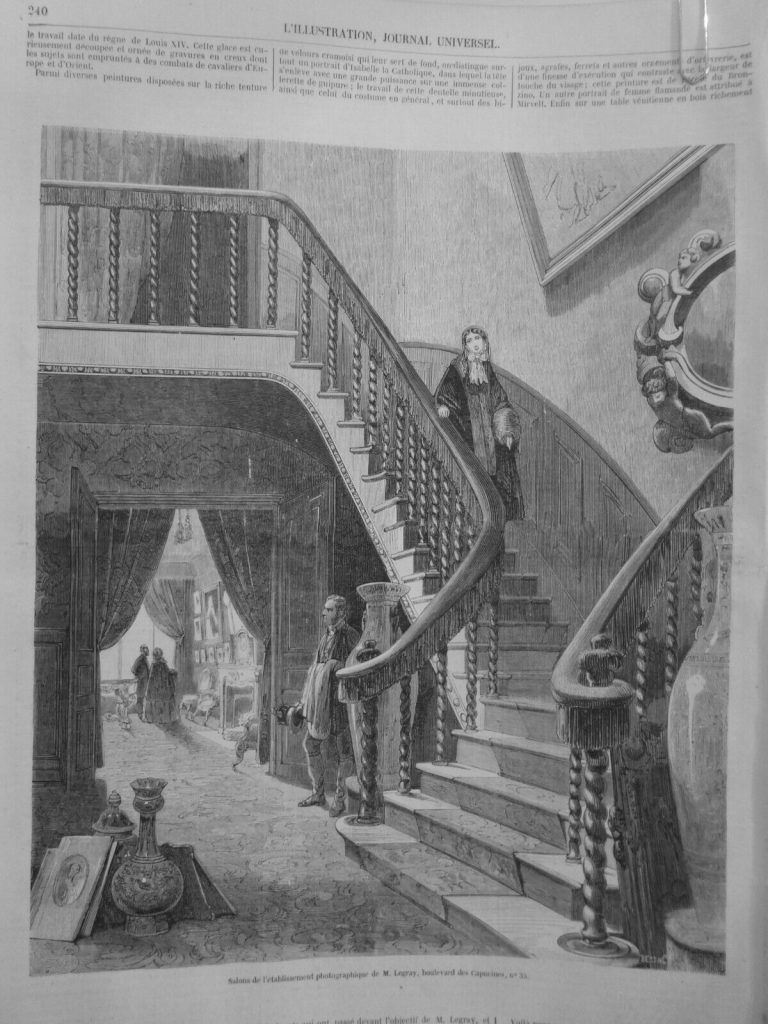

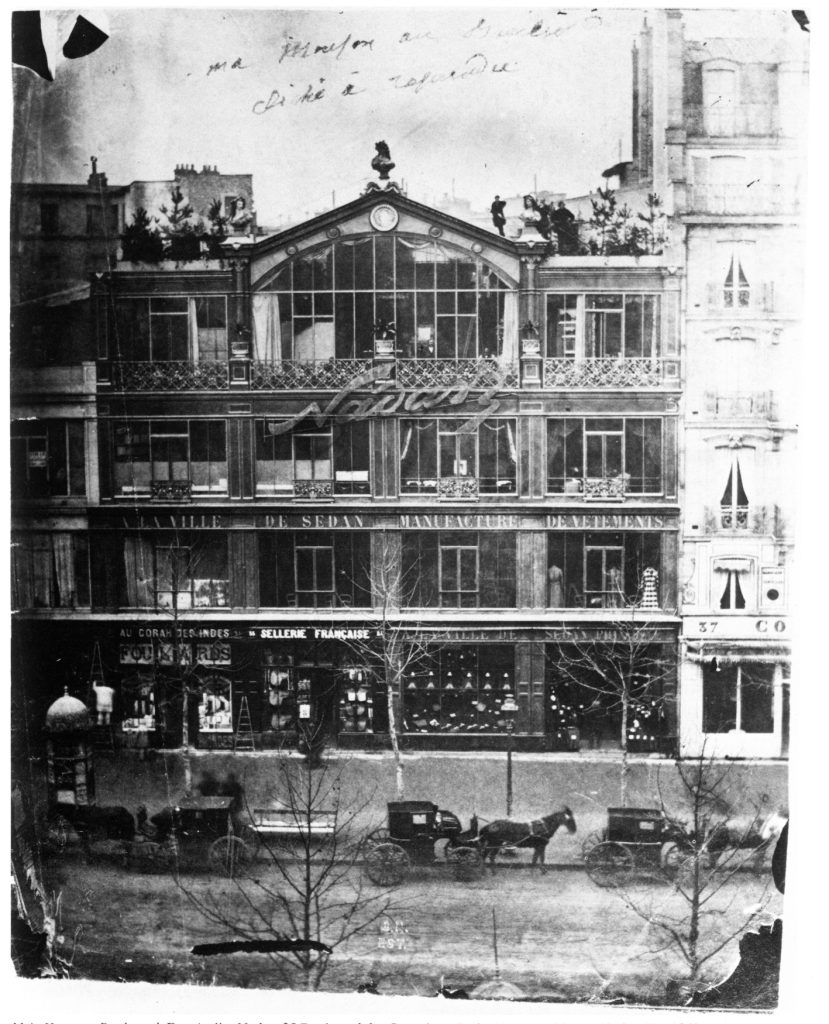

Opening of Gustave Le Gray’s Studio, 35 Blvd des Capucines, Paris, 1856. L’Illustration, Journal Universel, 27, no 685 (April 12, 1856): 240

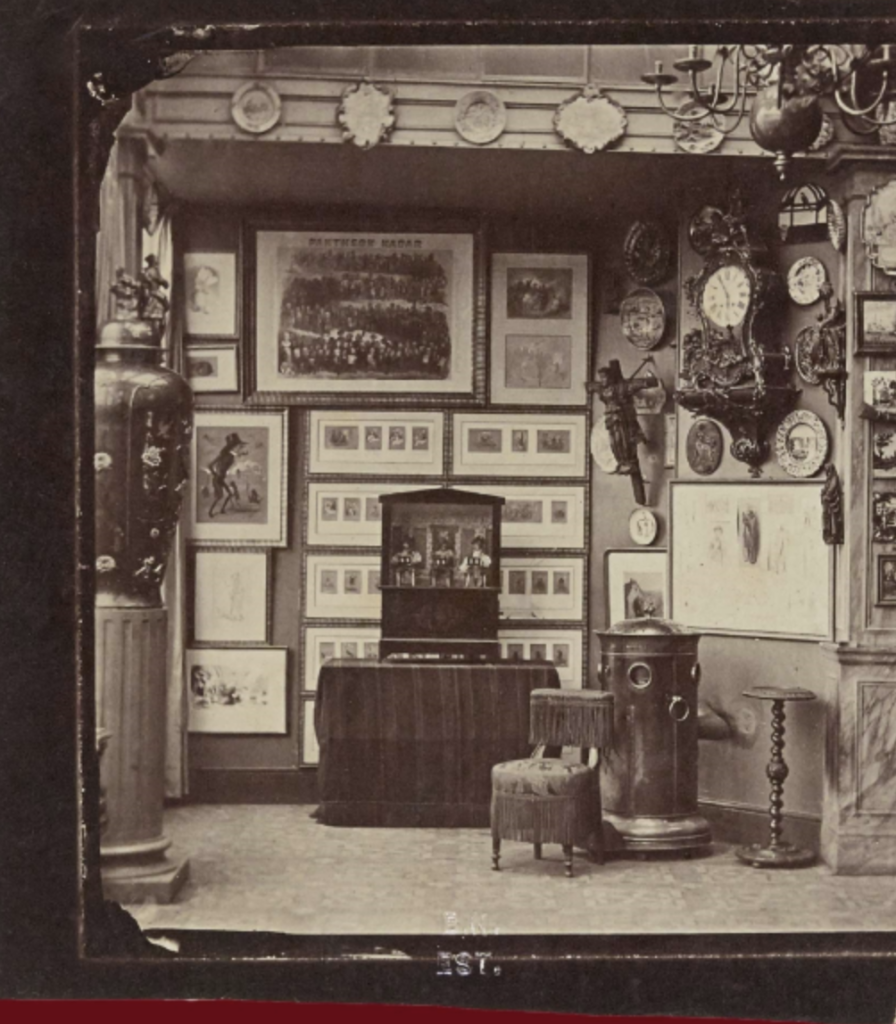

Flush with success and armed with 100,000 francs capital from the marquis de Briges, he established “Gustave Le Gray et Cie” in the fall of 1855 and opened a lavishly furnished portrait studio at 35 boulevard des Capucines (a site that would later become the studio of Nadar and the location of the first Impressionist exhibition). L’Illustration, in April 1856, described the opulence intended to match the tastes and aspirations of Le Gray’s clientele: “From the center of the foyer, whose walls are lined with Cordoba leather … rises a double staircase with spiral balusters, draped with red velvet and fringe, leading to the glassed-in studio and a chemistry laboratory. In the salon, lighted by a large bay window overlooking the boulevard, is a carved oak armoire in the Louis XIII style … Opposite over the mantelpiece, is a Louis-XIV-style mirror … [and] various paintings arranged on the rich crimson velvet hanging that serves as backdrop … Lastly on a Venetian table of richly carved and gilded wood, in mingled confusion with Flemish plates of embossed copper and Chinese vases, are highly successful test proofs of the eminent personages who have passed before M. Le Gray’s lens…However, the principal merit of the establishment is the incomparable skill of the artist…Despite a steady stream of wealthy clients, the construction and lavish furnishing of his studio ran up huge debts…On February 1, 1860, Gustave Le Gray et Cie was dissolved.

5.4

| Felix Nadar:

Beyond the Documentary Portrait

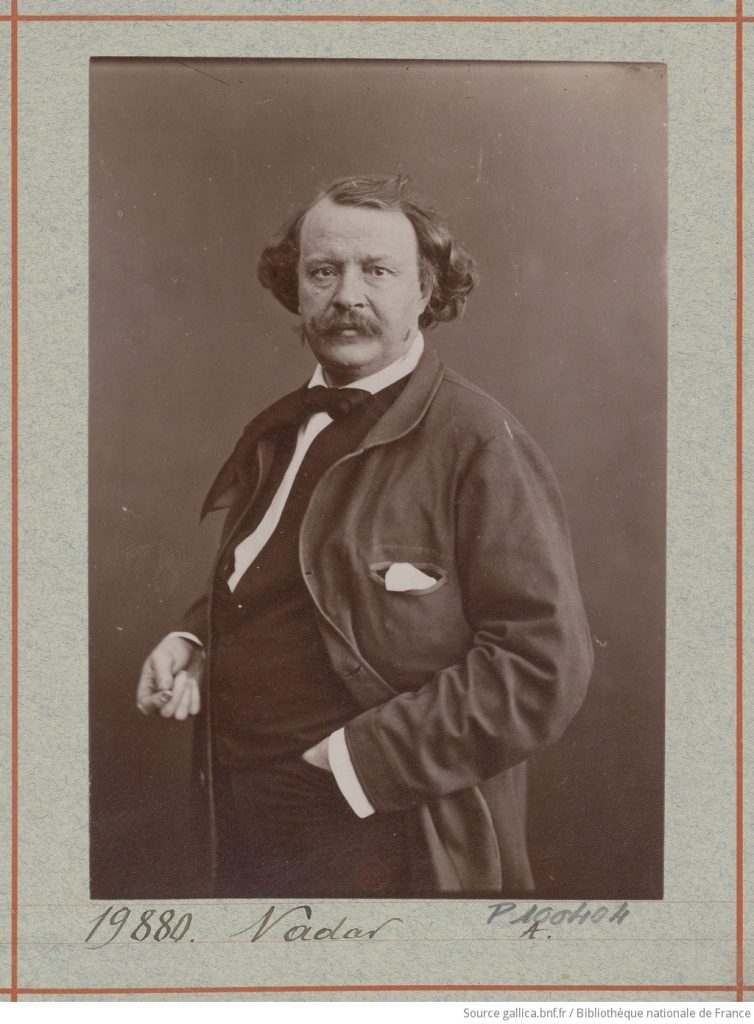

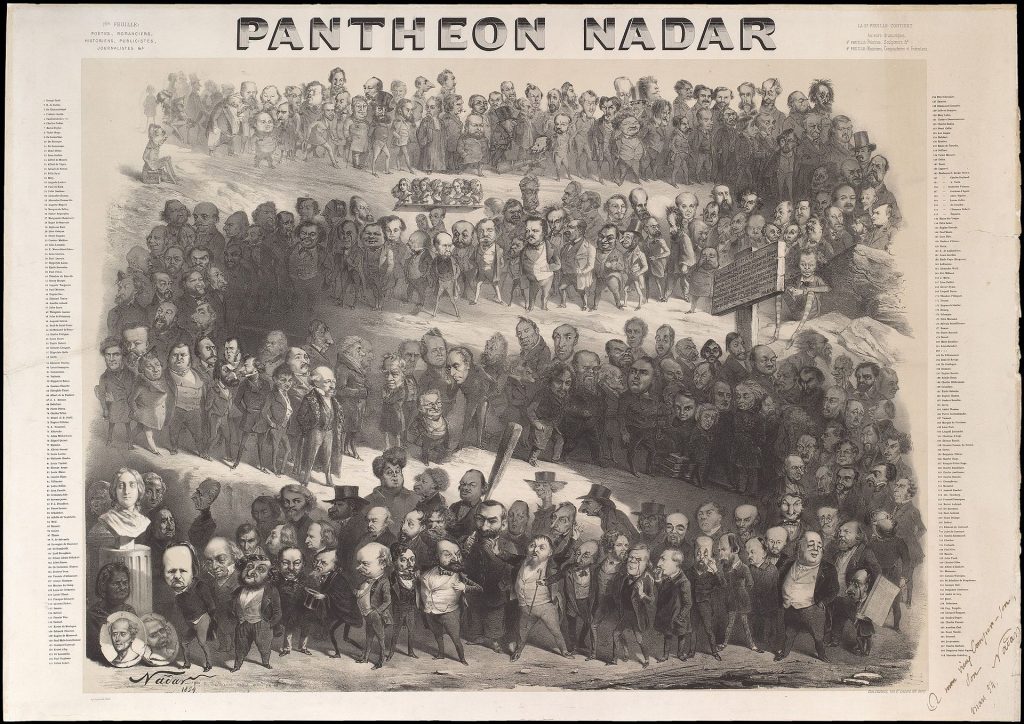

Before taking up photography in 1854, Nadar worked as a novelist, journalist, editor, and caricaturist for the Parisian press. The year he took up photography, he self-published his first lithograph entitled the Panthéon Nadar, a set of two large lithographs that comprised caricatures of prominent Parisians. He first created photographic portraits of the persons he went on to caricature.

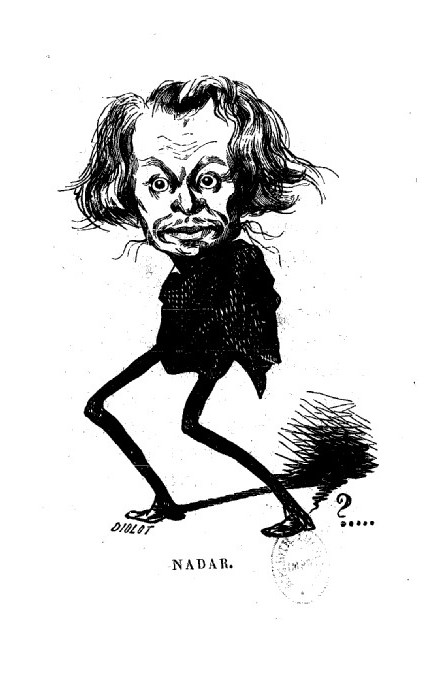

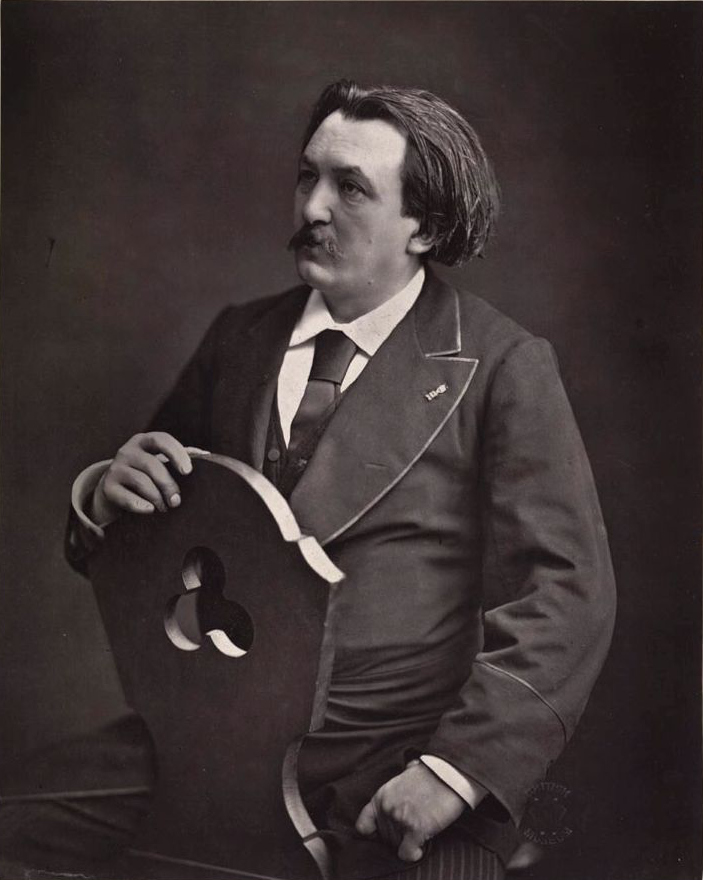

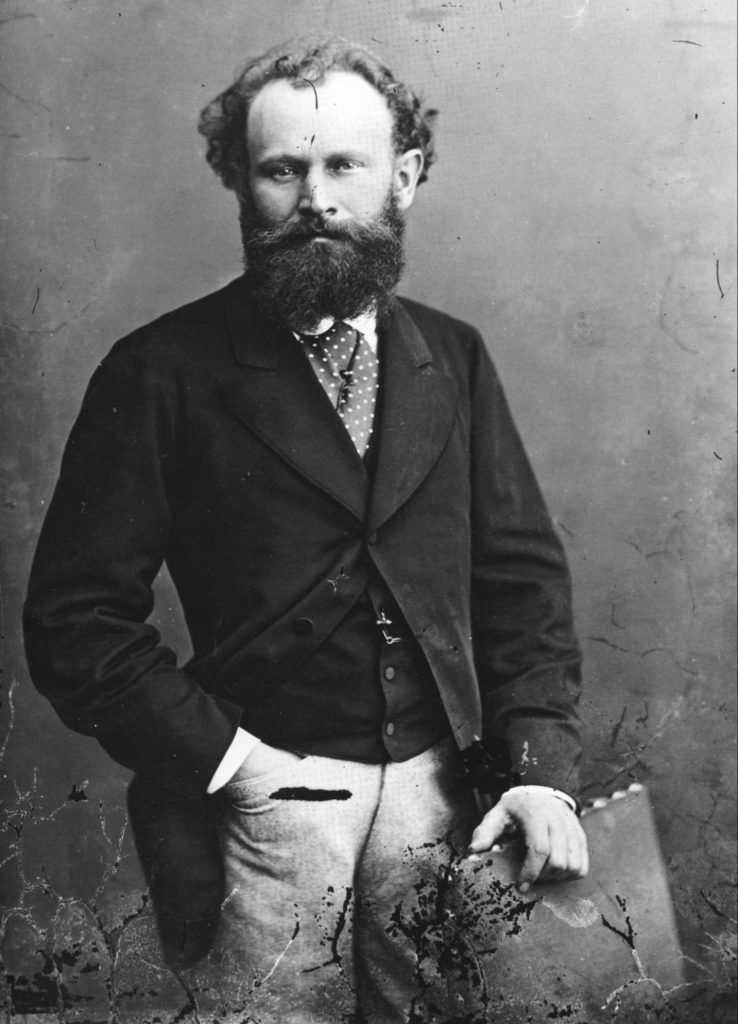

Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon), the flamboyant French portrait photographer caricaturist, writer, and aerial photographer, was Gustave Le Gray’s student. The name Nadar derives from his political caricature-related moniker, tourne a dard which means “biting sting.”

Nadar included himself among the two hundred prominent Parisians, each carefully articulated with identifying characteristics and idiosyncrasies. These lithographs reflect the elements that remained consistently important to Nadar: first, the carefully observed likenesses that captured his subjects’ qualities and accomplishments and second, the celebrity status bestowed on his work and himself, by virtue of the individuals represented.

Jullian Lerner has devoted considerable attention to Nadar’s self-portraits as “performative specimens” deployed for social purposes. He writes in Experimental Self-Portraits in Early French Photography (Routledge, 2021): “Nadar seems to have understood his likeness and his life story as signatures too—distinctive flourishes that could be amplified and redrawn to produce an identifiable pattern. He made an astounding number of self-portraits. There were literary and graphic self-portraits in the comic press, on party invitations, and in works of art criticism. Each charged portrait underscored the same peculiar Nadarian traits.”

The traits he made sure he captured in his self-image included his spindly appearance, messy red hair that was as unruly as his opinions, and his lively eyes.

By 1858, three years after opening his first studio Nadar was one of Europe’s most celebrated portrait photographers. In 1860 he moved to lavish new studios on the Boulevard des Capucines.

His atelier attracted the elite society of the boulevard, the intelligentsia of Paris, and the leading bohemian lights of the era, including artists, actors, and writers.

There was not just one, but several Nadars. Along with Félix, his brother Adrien and son Paul also abandoned their last name and adopted the pseudonym that Félix had come up with. And yet, there is just one Nadar, more precisely a brand, a collective singular that refers not only to a family, but also to a firm that employed a great many collaborators. In the 19th century, Nadar was a brand with a powerful cultural aura. (“The Nadars: A Photographic Legend” http://expositions.bnf.fr/les-nadar/en/the-art-of-the-portrait.html)

In contrast to his rivals, Nadar equated his work with art rather than industry or science, his portraits aspiring to aesthetic significance and commercial success. He added value to his photographic images by exploring the psychological dimension of his sitters, aiming to reveal their personalities, not just produce attractive photos. His subjects were directly and naturally posed, in contrast to his contemporaries’ stiff formality and prop use.

The space of trusting exchange Nadar developed with his clients enhanced the descriptive potential of his portraits. Max Kozloff writes in “Nadar and the Republic of the Mind” (Artforum 15 no. 1 (September 1976): 28-39): “With the latitude now permitted, or that welled up amiably in the ‘contract’ between photographer and sitter, facial mobility came into its own.”

Kozloff continues,

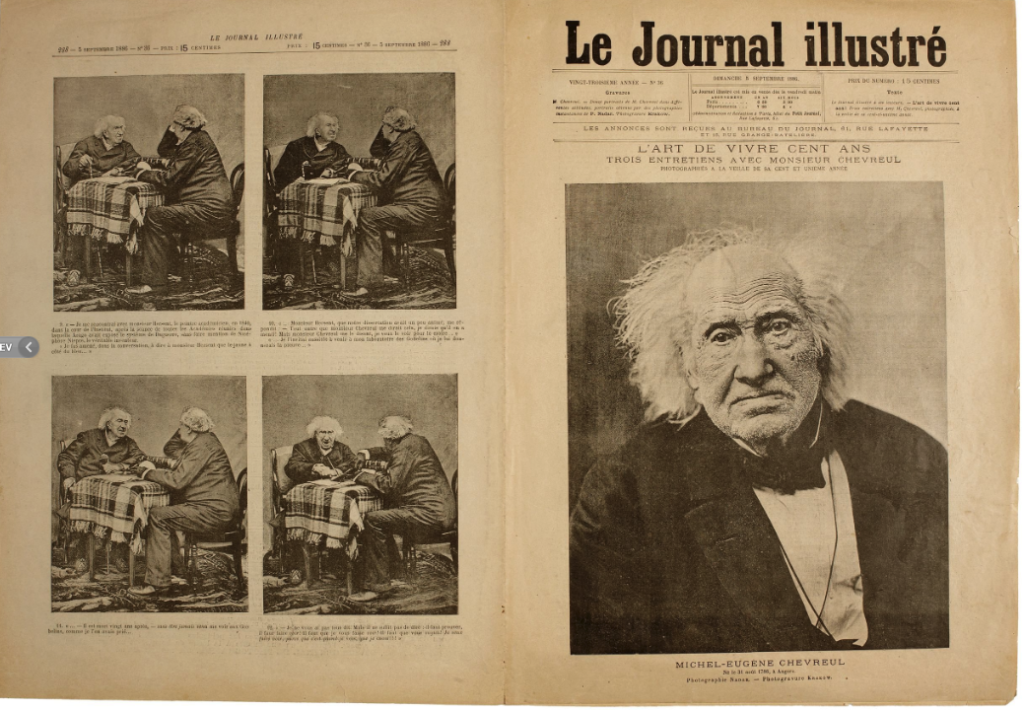

For proof, one has only to look at the first published interview in the history of photography, in Le Journal Illustré, August 1886, for which Paul Nadar took innumerable shots of his father conversing with Chevreul, the famous chemist and color theoretician. Not only was this technically advanced, made possible through a fast shutter (1/133 of a second), but it epitomized the ongoing candor that suffuses Nadar’s portraits.

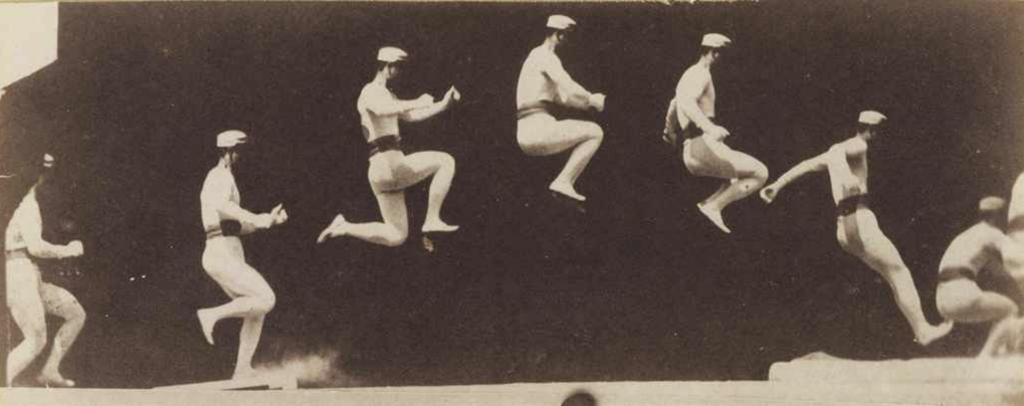

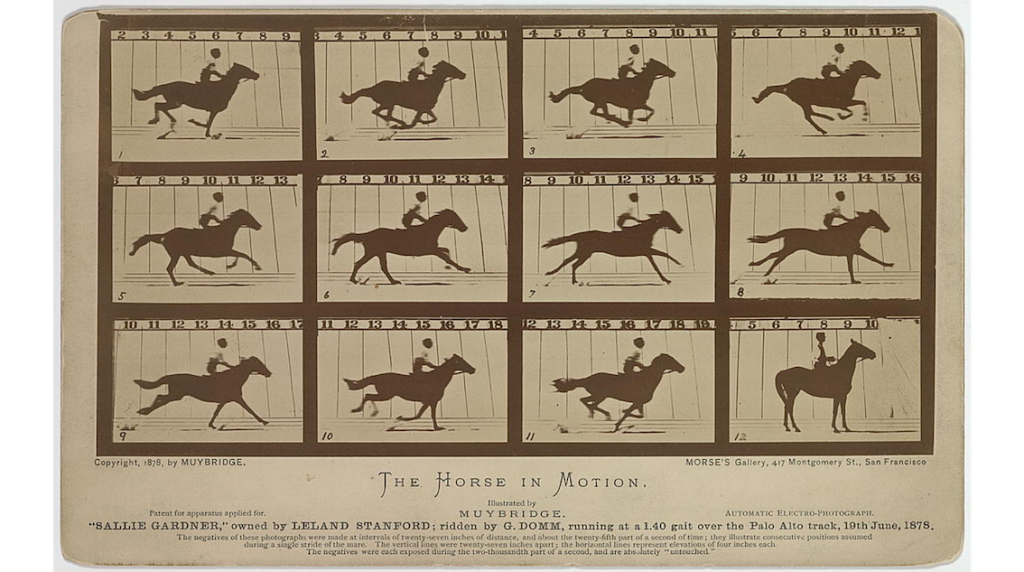

Perhaps even further, he might have wanted to demonstrate how to overcome the fragmentary aspect of the still photograph by multiplying stills through a short time span. In this he could be said to have hinted, in portraiture, at what Marey, whom he admired, and Muybridge, whose work he surely knew, were accomplishing in the representation of human and animal movement.

During the 19th century, photographers’ clientele could help them achieve recognition and fame. Nadar cultivated his reputation as a celebrity photographer, and his growing notoriety reciprocally gave prestige to those able to commission a portrait by him.

Jullian Lerner explains Nadar’s unique approach in Experimental Self-Portraits in Early French Photography (London: Routledge, 2021). Nadar’s portraiture “… was rarified and spiritual, the resemblance intimate and earnest, and the framing austere. Reducing the noise of backdrops, furnishings, and fashionable attire that cluttered the full-figure poses of rival studios, Nadar zoomed in on his sitters’ faces. And because his premium full-plate prints (25 × 19 cm) were “life-size, they staged an intense tête-à-tête between the sitter and the viewer.”

Nadar eschewed the montage format because it disrupted the intimacy he sought, his “quest for photographic purity and a truth of the face.” His austere approach to portraiture complimented his famous sitters’ intellectual, bohemian, and anti-materialist disposition. These friends were his preferred clientele early on, privy to discounted prices for prints while allowing him to keep the negatives for future dissemination. Lerner continues:

Thus Nadar accumulated a photographic “image bank” of Contemporary Figures that he could exploit in a number of ways. He sold portraits to publishers, for use as the basis of illustrations in journals and books (reproduced for print publication in wood engraving). After 1861, he also sold celebrity portraits to anonymous buyers off the street, in the commercially optimized form of cartes de visite. At first reluctant to embrace this small, cheap, mass-producible format invented by his rival Andre-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, Nadar eventually decided to cash in on the public’s mania for celebrity cartes, which all manner of citizens avidly collected and arranged in albums alongside portraits of relatives and friends.

Nadar, the businessman, astutely cultivated a niche market and carefully catered to it. He rejected Napoleon’s Republicanism to appeal to Bohemian independence and opposition. As such, he was an outlier. Others who aspired to succeed believed that achieving recognition required casting a wide net and adherence to academic criteria. For mainstream photographers, as Lerner explains, “pinning their hopes on a marginal avant-garde whose own status was far from secure would be imprudent.”

When the studio on Boulevard des Capucines declared bankruptcy due to over-expenditures, the Nadar firm moved to a more affordable site on Rue d’Anjou. They gave up studios that boasted a rooftop terrace, a ground floor with a garden, a glass-roofed atrium, and enormous windows on the upper floors. Still, the Rue d’Anjou studio had huge windows on the upper floors. Before the advent of artificial light and more sensitive processes, natural light was indispensable for taking and developing photographs. “…natural light was indispensable for taking and developing photographs… The photographers could create a range of variations and effects thanks to filtering blinds, and with reflectors and screens.”(http://expositions.bnf.fr/les-nadar/en/the-art-of-the-portrait.html#the-studios)

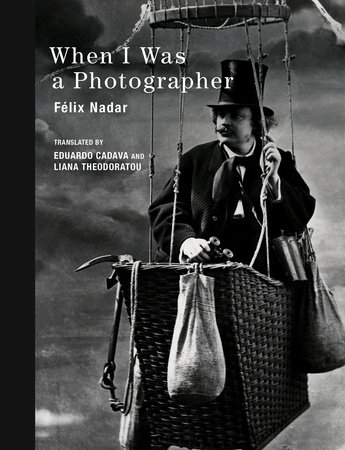

Nadar was a personality that thrived on adventure. His interests extended well beyond photography, as Philip McCouat writes in “Photography, Ballooning, Invention and the Impressionists.” (https://www.artinsociety.com/the-adventures-of-nadar-photography-ballooning-invention–the-Impressionists.html):

Photography, while absorbing, was by no means Nadar’s only interest. Along with several of his friends, including Jules Verne and Victor Hugo, he was fascinated by the idea of human flight. Accordingly, during the 1850s, Nadar enthusiastically began hot-air ballooning.

Ballooning offered an escape from the cares of the world. He described the sensation of ascending as a ”free, calm, levitating into the silent immensity of welcoming and beneficent space,” which presented “an admirable spectacle…. an immense carpet without borders… what purity of lines, what extraordinary clarity of sight… with the exquisite impression of a marvellous, ravishing cleanliness!”

For Nadar, the sublime views obtained from an aerial balloon floating above the city were a compelling “invitation to the lens.” They spurred his

Manet’s View of the 1867 Exposition Universelle would not have been as complete a view of modern Paris without the inclusion of Nadar hovering over the city in an air balloon, as seen at the top right of the composition.

McCouat continues:

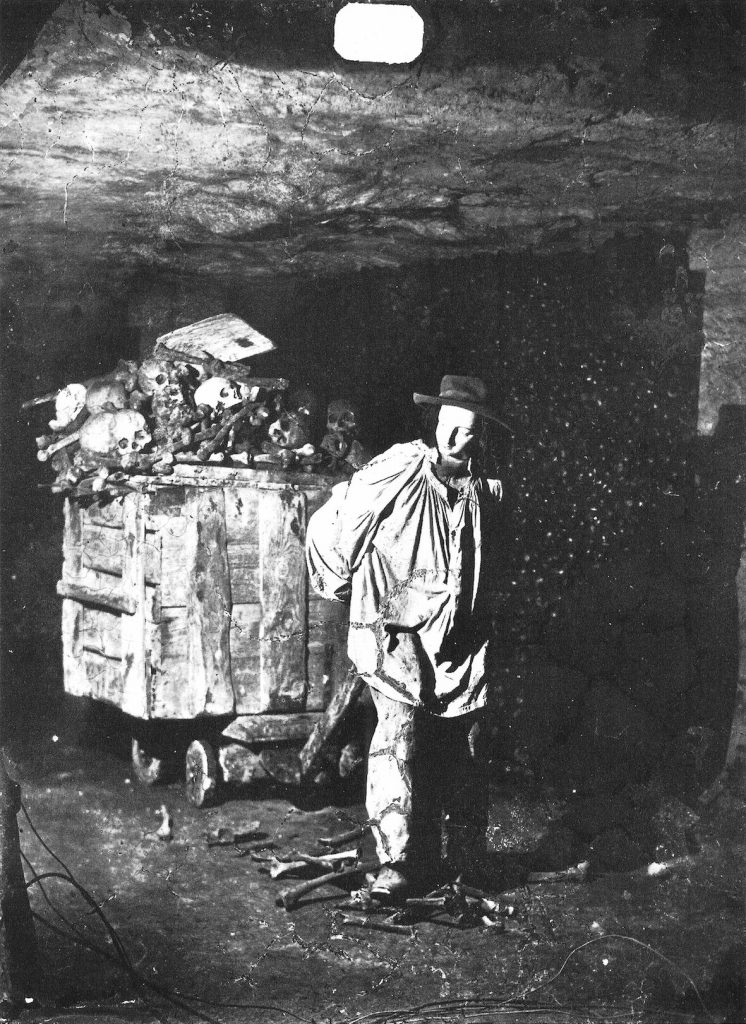

Not content with photographing from the air, Nadar had also begun on a novel project to photograph underground, using only electric light. This would pose some considerable challenges. Photography had always been associated with light, its very name means “a drawing of light,” and here was Nadar saying that he could take photographs without any natural light at all.

In 1900, towards the end of his life, Nadar published Quand j’étais photographe, translated into English and published by MIT Press in 2015. The book offers a collection of anecdotal vignettes, numerous portraits and character sketches, and meditations on his photographic history.

Nadar’s explorations into the bust-length portrait remained his primary source of livelihood. Along with the full-length carte-de-visite developed by Disdéri, these two modes of portrait photography dominated the field from around 1855 until 1870.

Their differences may seem minute, but they are significant. The commercial carte was inexpensive and readily available. The bust-length portrait, considered of greater aesthetic value, was the province of the elite. The carte’s attention to pose, clothing, accessories and setting reflected a sitter’s status, whereas faces and personalities could not be easily discerned. Nadar’s three-quarter view, on the other hand, with its focus on facial expression and attention to aesthetic conventions, could render more unique portrayals.

Walter Benjamin writes:

These images were taken in rooms where every customer came to the photographer as a technician of the newest school. The photographer, however, came to every customer as a member of a rising class and enclosed him in an aura which extended even to the folds of his coat or the turn of his bow tie. For that aura is not simply the product of a primitive camera. At that early stage, object and technique corresponded to each other as decisively as they diverged from one another in the immediately subsequent period of decline. Soon, improved optics commanded instruments which completely conquered darkness and distinguished appearances as sharply as a mirror.

However, Benjamin overlooked the evolvement of portrait photographic experimentation in Paris.

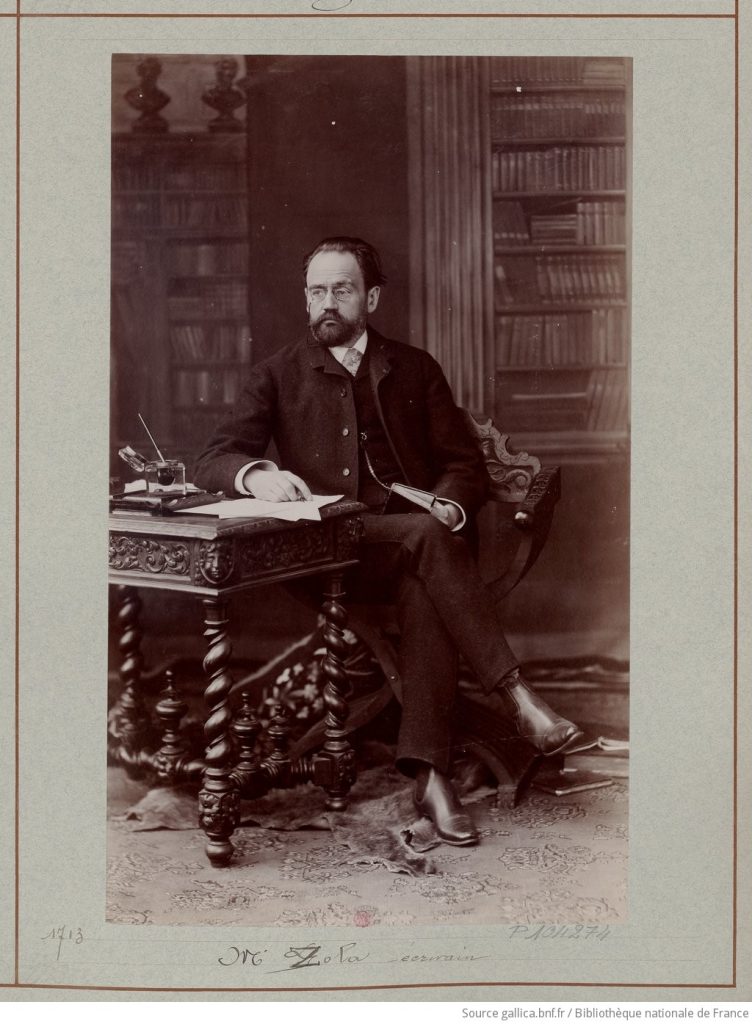

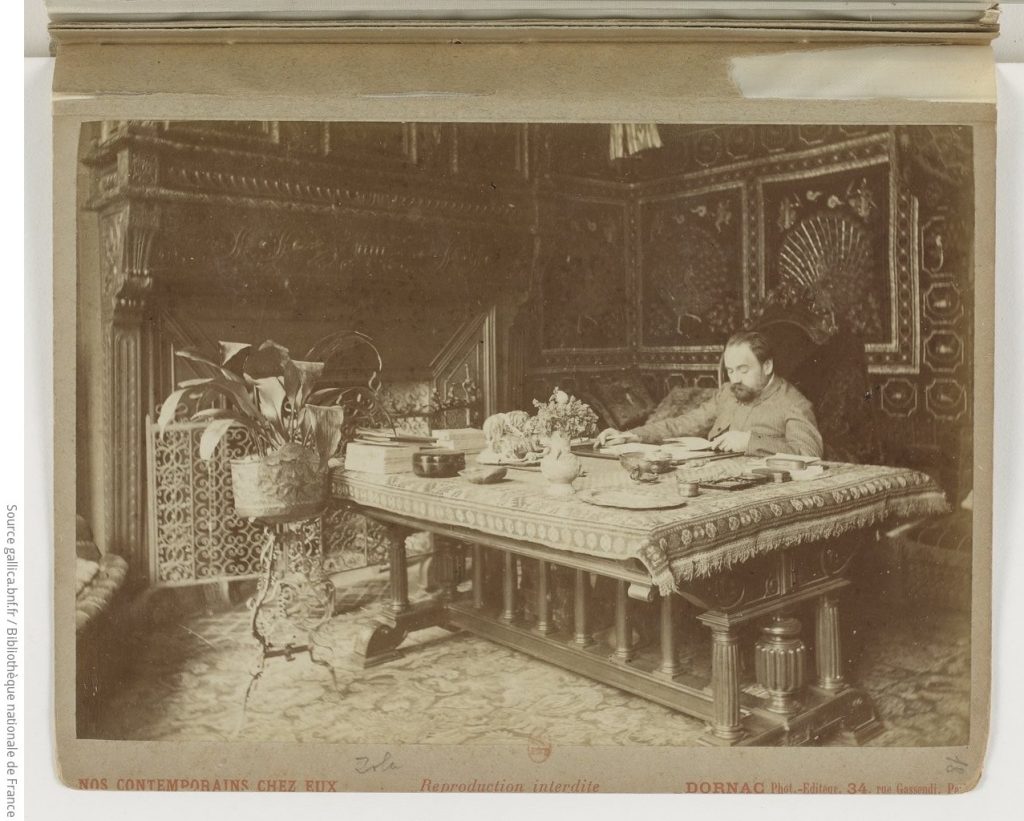

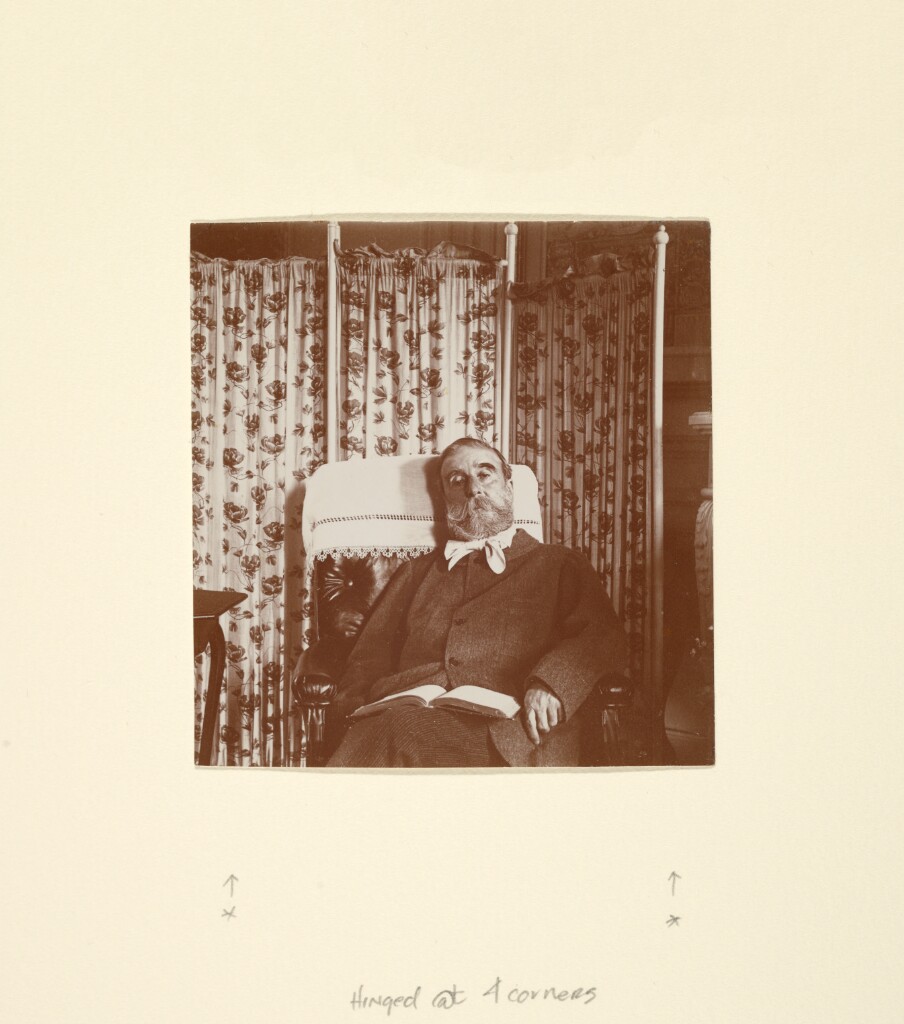

The photographer Paul Cardon, known as Dornac, specialized in photographic portraits of famous men in their homes or at work. Active from the late 1880s, his images were published in Nos contemporains chez eux. His innovative process relied on the fact that dry plates could be prepared in advance and developed long after exposure, eliminating the need for a portable darkroom.

Elizabeth Emery, in “‘Dornac’s at Home’ Photographs, Relics of French History” (Proceedings of the Western Society for French History 36 (2008): 209–224), writes about Dornac’s ‘at home’ photographs and their implications for the fin-de-siècle cult of celebrity:

As the camera began to chronicle the private life of public figures and as editors published these images in the flourishing periodical industry, viewers became aware of the milieu surrounding famous figures. No longer mysterious and untouchable, grands hommes (“great men,” though well-known women were also occasionally included under this rubric) began to be treated like scientific specimens on display in their native “habitats.” Photography was thus partly responsible for facilitating a shift from interest in grands hommes as revered national heroes, worthy of public monuments, to more intimate and obsessive celebrity cults housed in private rooms, apartments, and museums.

…

Gaston Tissandier, renowned pioneer of hot air balloons, editor of the journal, the author of books about photography, and himself a figure in the Nos Contemporains series, paired the photographs with accompanying texts in which he qualified Dornac’s goals as eminently ‘scientific.’The influence of Dornac’s endeavour spilled over into the commercial studios of photographers such as Félix Nadar, Pierre Petit, and Étienne Carjat. They appropriated his ideas by creating staged settings that recreated domestic backgrounds. This is visible, for example, in Zola by Nadar, where one can see the canvas roll of the backdrop visible on the floor. The table is equally a prop, reappearing elsewhere in Nadar’s works, such as in the portrait of Edmond de Goncourt.

In contrast, the authenticity of Dornac’s photographs remained constant. He captured minute details that were, according to Tissandier, “witnesses of their thoughts and works…” He believed that Dornac’s use of photography, his emphasis on what was there as opposed to what was imagined, made “the most precious auxiliary of the exact sciences…”

Emery:

The early nineteenth-century ideal of a ‘monument in stone,’ an authorized image of the ‘great man’ erected in a public space to commemorate his cultural importance, thus gave way, as we have seen, to much more fragmented and complex images, often disseminated by photographs, by which the public sought to understand famous figures more fully… Dornac’s ‘at home’ photographs went a step further, creating the illusion of even greater intimacy by providing access to the environment in which grands hommes lived and worked. By shifting emphasis from physical appearance to milieu, his series allowed viewers to vest the objects surrounding his famous subjects with near-magical powers: as ‘relics,’ they seemed to retain some of the spirit of those who had touched them.

Such evolutionary advances in photography as a medium of visual communication and expression testify to its permeating influence in society within short decades of its birth. As Malcolm Daniel has asserted, “The medium’s most profound and lasting expressions, however, were no longer the work of its leading professionals, but rather of those who consciously set themselves apart from the accepted rules of commercial practice and took photography into new arenas of technique, subject, and expression.”

5.5

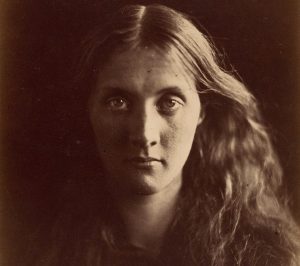

| Julia Margaret Cameron: Art Photography and Pictorialism

The British artist Julia Margaret Cameron was among the early photographers who did take the medium into what Daniel describes as “new arenas of technique, subject, and expression.”Perhaps one of the most painterly portraitist photographers of the nineteenth century, Cameron’s pursuit of the artistic potential of photography challenged the medium’s status as the most accurate replicator of reality. This dimension of photographic portraiture most closely reflected the concerns of a younger generation of artists more interested in evoking truthful images through atmosphere and ambiguity. In her cultivation of ambiguity and manipulation of the photographic process, she was an important pioneer of Pictorialism and the idea of photography as a contemporary art form.

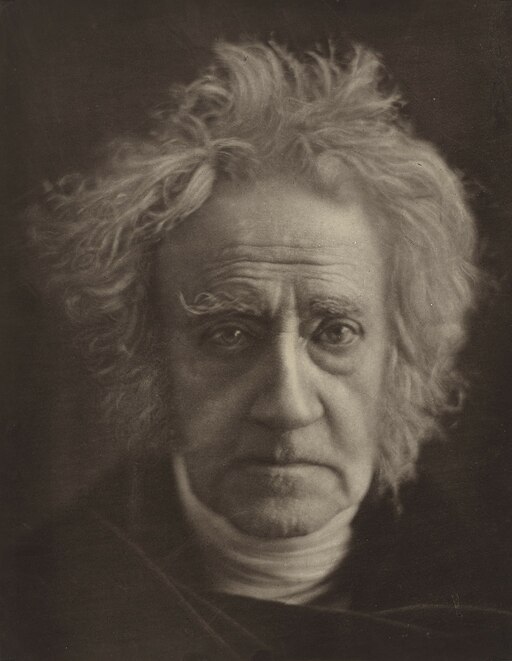

Cameron may have entered the field as an amateur female photographer, but she approached her work professionally. She deliberately marketed and exhibited her photographs but made clear that her interests were not in pursuing commercial portrait photography. Cameron considered herself an artist and described her aspirations “to ennoble photography and to secure it for the character and uses of high art” to her mentor, the scientist Sir John Herschel.

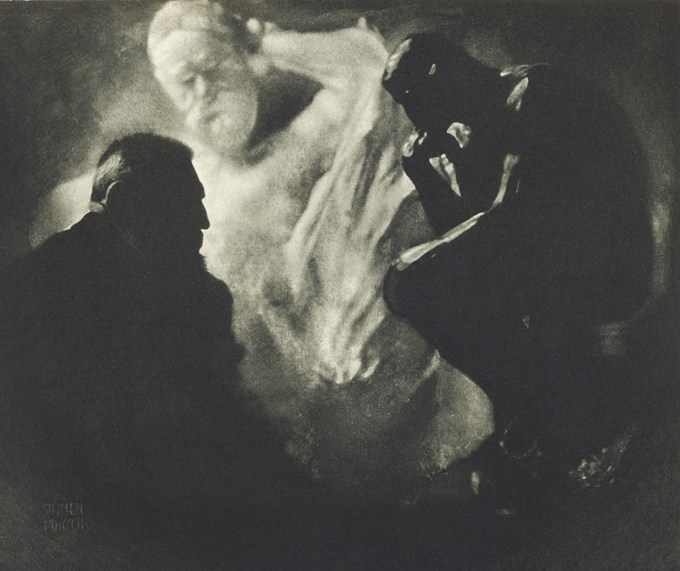

Cameron’s stylistic manipulations are in evidence in this portrait of Herschel, a scientist and experimental photographer. The MOMA entry for the work describes it as follows:

No commercial portrait photographer of the period would have portrayed Herschel as Cameron did here, devoid of classical columns, weighty tomes, scientific attributes, and academic poses—the standard vehicles for conveying the high stature and classical learning that one’s sitter possessed (or pretended to possess)… she had him wash and tousle his hair to catch the light, draped him in black, brought her camera close to his face, and photographed him emerging from the darkness like a vision of an Old Testament prophet.

Cameron employed wet collodion on glass negatives and albumen prints to apply the aesthetic principles of painting to portrait photographs. She was among the first to combine close cropping with softly focused imagery, moving her work beyond objective representation. Determined to capture the essence and character of her subjects, Cameron engaged the ethereal and dreamlike impressions created by the combination of diffused focus, manipulated lighting, veiling shadows, and expressive posture.

Julia Margaret Cameron was 48 years old in 1863 when she received her first camera as a birthday present from her daughter and son-in-law. The gift, meant to be a fun distraction, inspired the career of one of the finest Victorian-era portrait photographers.

Liz Jobey describes the portrait of Annie Philpot, which Cameron called her “first success,” in First Light, her review of the exhibition Julia Margaret Cameron: 19th-Century Photographer of Genius held at the National Portrait Gallery in London in 2003.

(https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2003/jan/18/photography.artsfeatures):

At 1pm on January 29, 1864, a little girl with cherubic features and scraggy, shoulder-length hair was buttoned into her winter coat, waiting patiently for her photograph to be taken. In front of her, a short, stocky, middle-aged woman fitted another glass plate into the back of her huge camera and begged the child to keep still. She was probably counting, too; it could take up to five minutes for the image to be fully exposed. If the girl was bored, she didn’t show it. Her face, turned in half-profile to catch the light, was composed but alive, its curves heightened by the contrast between shadow and light. It was a happy result – we know, because the photographer wrote to the girl’s father later that day: “My first perfect success in the complete Photograph owing greatly to the docility & sweetness of my best and fairest little sitter. This Photograph was taken by me at 1pm Friday Jan 29th Printed Toned – fixed and framed all by me & given as it now is by 8pm this same day Jan 29th 1864. Julia Margaret Cameron.”

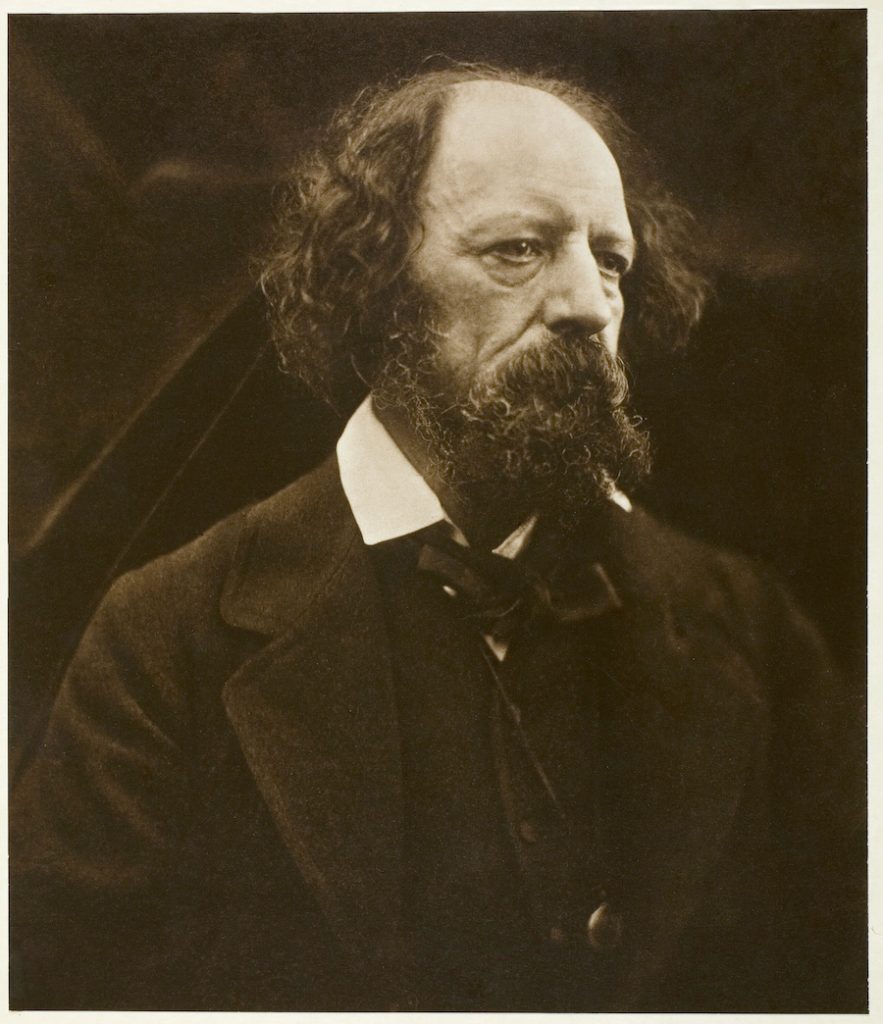

Cameron, of British descent but born in Calcutta, was a well-read, cultured woman with connections to literary, artistic, and scientific figures.Like Nadar, Cameron set out to capture the elite world of celebrities she frequented. She did so because she had ease of access to her subjects and strategically, knowing that portraits of Britain’s stars were more likely to attract sales and future clients. Cameron’s portraits, included the celebrated poet Alfred Lord Tennyson (a friend and neighbour at Freshwater),

and Alice Liddell (who was also a photographic subject for Lewis Carroll as a child and inspired the 1865 children’s classic novel Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland),

as well as her niece Julia Stephen, the mother of the author Virginia Woolf.

Cameron defied photography’s early conventions, “using dramatic lighting and forgoing sharp focus in favour of conscientiously artistic effects that appealed to viewers familiar with Rembrandt’s chiaroscuro and the traditions of Romanticism.” The photographic press severely criticized her for her bold disregard for sharp detail and seamless printing that ensured the “correct” replication of reality, to which she replied, “What is focus and who has the right to say what focus is the legitimate focus?” (Nineteenth Century Photography, https://arthistoryteachingresources.org/lessons/nineteenth-century-photography/)

Her approach and aesthetic sensibilities would influence the future of the international Pictorialist movement, which insisted on personal expression and the recognition of the medium as fine art and was popularized by slightly later practitioners such as Edward Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz.

As Mina Markovic, in an introductory text on the artist for the National Gallery of Canada (https://www.gallery.ca/photo-blog/focus-on-the-collection-julia-margaret-cameron-1815-1879), concludes: “Following her death in 1879, Cameron’s influence on early art photography persisted…. Cameron is one of the few 19th-century women photographers consistently recognized for her contributions to the photo-historical canon.”

5.6

| Modern Impressionist Portrait Paintings and The Impact of Photographic Techniques

The prevalence of portrait photography during the latter 19th century influenced the practice and formal qualities of painted portraiture. Photography was now considered the gold standard in optical realism, which freed painters from the burden of realistic replication and inspired new compositional strategies and experimental pictorial techniques. In addition, the use of photographs as references was a labour-saving practice. It reduced the time and tedium of constant studio sittings and provided visual information no longer available to the artist after a studio visit.

Courbet’s Proudhon and His Children, for example, painted posthumously from a photograph, does not lack in likeness or characterization for its source; rather it is enhanced by details captured as a visual record of a past moment in time

The German artist Franz von Lenbach advocated for the use of photographs as a basis for portraiture and was among the earliest painters to do so. His first portrait commissions date after 1881, when he was awarded a third-class medal for one of his portraits at the Grande Exposition in Paris.

Lenbach utilized a method invented by the Belgian photochemist and professional photographer Désiré van Monckhoven that projected a photographic image onto a canvas as an under-sketch, a technique called photo-sciagraphy. In 1863 van Monckhoven registered a patent for an optical apparatus that enlarged imagery by projection, for which he received a bronze medal at the Exposition Universelle of 1867. Soon after, he began manufacturing a device that could be built into a darkroom wall.

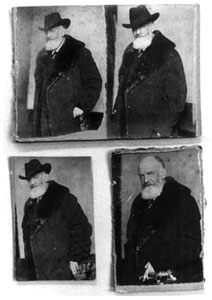

Lenbach’s process involved taking several photographs of a sitter in different poses, which he then enlarged on a canvas, outlined in paint, and added tone and colour. By the second time a sitter arrived, their portrait was nearly complete.

Carola Muysers explains Lenbach’s procedure in “Physiology and Photography: The Evolution of Franz von Lenbach’s Portraiture” (Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 1, no. 2 (Autumn 2002), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn02/256-physiology-and-photography-the-evolution-of-franz-von-lenbachs-portraiture):

By the early 1880s the portraitist regularly hired professional photographers such as Friedrich Wendling, Adolf Baumann, and Karl Hahn to photograph his sitters, an effort made easier by the dry plates that had recently come on the market, and by the box camera.

Lenbach himself described his new method: “Once I have drawn the figure from life (and I always do that first) and I have had the movement photographed, it becomes a matter of fleshing it out with the help of photography and the imagination.” What distinguished Lenbach’s method was not the production of portraits with the aid of sketches and photographs but his use of photographs of movement and his decision to “flesh out” these photographs rather than slavishly copy them.

The following example illustrates Lenbach’s standard procedure. About 1895 the artist was commissioned to paint a portrait of the Egyptologist Georg Ebers. Ebers came to Lenbach’s studio in the company of his son Hermann, who left an account of what occurred there. The artist began by replacing Ebers’s uninspiring coat with a dark, fur-trimmed cape and the slouch hat of a scholar. Under the pretext of getting to “know the model by heart,” he first engaged the sitter in conversation, in the course of which Hermann heard clicking sounds behind some black curtains. It turned out that Karl Hahn was snapping photographs of the subject whenever Lenbach gave him a discreet hand signal.

Four of the twenty photographs Hahn took during that session survive. All show Ebers before a white background and the differences between his poses are slight, yet the psychological effects are astonishingly varied. In one shot, Ebers tilts his head forward menacingly, his eyes hidden by the brim of the hat. A second shows him standing straight and looking up to the left with a fixed, hostile gaze. In the third, he looks directly at the viewer, and a slight twist of the head and body lends a sense of energetic movement to the whole. The fourth photograph captures a glowering Ebers holding the hat in his hand.

The Ebers series shows that Lenbach had two major concerns. One was that the sitter not be conscious of being photographed. The other was that the sitter respond naturally, rather than fall into an stereotypical yet uncharacteristic pose.

How did Lenbach “flesh out” his portraits? In other words, how did he move from the photographs of movement to the finished portrait? The artist would paste a series of snapshots on a piece of cardboard. (At first he used single shots, later contact prints.) Seeing these movements in sequence gave him a sense of the range of the sitter’s expressions and helped Lenbach select the most characteristic one for the portrait. Once the best parts of several photographs had been selected, the artist copied them onto his canvas. Beginning with such traditional aids as square grids, Lenbach proceeded to tracings and finally to photopeinture. In this last method he would enlarge and print a negative on a specially prepared canvas, placing washes on the barely visible positive that was ultimately covered with lights and shades. The painting was never an exact copy of a single photograph, however, as the artist often incorporated elements from several photographs and drawings.

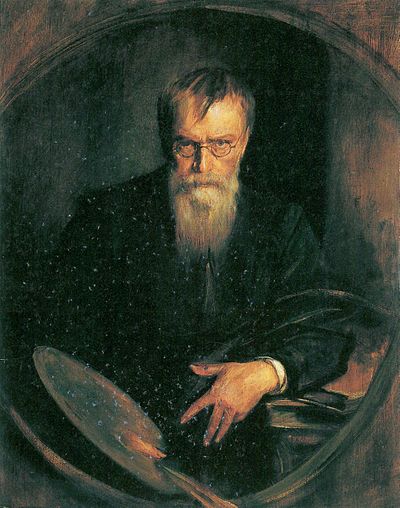

Lenbach used this technique to paint his self-image throughout his career. In this last one, executed a year before his death, he depicts himself standing face forward as he leans onto a console to his left. His direct gaze is penetrating, entirely focused on the viewer.

5.7

| Edgar Degas and the Influence of Photography

Impressionist artists painted portraits at a time when traditional portraiture, initially exclusive to the wealthy and powerful, had expanded to include the bourgeoisie. The democratization of the portrait, and the ensuing barrage of photographic images, spurred painters to innovate and reinvest portraiture with new value.

As Linda Nochlin reminds us in Making It Modern: Essays on the Art of the Now (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2022),

In a way, photography forced a certain innovativeness on ambitious artists. Today we cannot easily envision a world without the mass production and consumption of images – specifically, images of ourselves, our families, and our friends in the form of the snapshot, the wedding picture, or the class photograph – any more than we can envision a world without the mass production of clothing or other consumer products. The easy availability of images is so much a part of our experience that we cannot even imagine a situation in which a portrait might be a once-in-lifetime experience rather than an ongoing, multiple record of personal appearance and situation. The Impressionists lived in and reacted to a world in which the richness of individual and communal memory itself was being replaced by a plethora of cheap visual imagery.

Unlike photographers, Impressionist painters rarely took on commissions for portraits. Rather, they painted self-portraits, single and group portraits of friends and family, and pictures of colleagues and patrons. These portraits paid attention to the fragmented or absent context without losing sight of the individuality of the sitter. Contrary to Disdéri’s advice to photographers to select a pose that somehow represented the sitter’s typical attitude and expression, Impressionist portraits preferred postures and gestures that conveyed a spontaneous moment in time.

Duranty’s La Nouvelle peinture (The New Painting) of 1876, written on the occasion of the second Impressionist exhibition, echoed Degas’s outlook. He called for the study of “the relationship of a man to his home, or the particular influence of his profession on him as reflected in the gestures he makes” and “the scrutiny of the aspects of the environment in which he evolves and develops.”

Farewell to the human body treated like a vase with a decorative, swinging curve; farewell to the uniform monotony of the frame working … what we need is the particular note of the modern individual, in his clothing, in the midst of his social habits, at home or in the street …. By means of a back, we want a temperament, an age, a social condition to be revealed; through a pair of hands, we should be able to express a magistrate or a tradesman; by a gesture, a whole series of feelings.

Duranty argued that reality was perceived in flux and from varying perspectives. Unlike a camera, set up to capture a fixed view, a person’s view of a subject could alternate, it is “… sometimes very high, sometimes very low, missing the ceiling, getting at objects from their undersides, unexpectedly cutting off the furniture … He is not always seen as a whole: sometimes he appears cut off at mid-leg, half-length, or longitudinally. At other times, the eye takes him in from close-up, at full height, and throws all the rest of a crowd in the street or groups gathered in a public place back into the small scale of the distance.”

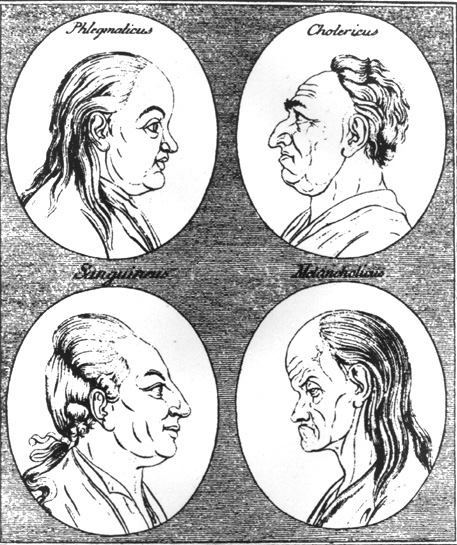

Duranty attempted to construct a vocabulary of “modern observation” based on analyzing physical, social, and racial characteristics. Degas himself wrote in his notebook: “Make of expressive heads (academic style) a study of modern feeling-it is Lavater, but a more relativistic Lavater so to speak, with symbols of today rather than the past.”

Johann Kaspar Lavater was a Swiss poet, writer, philosopher, physiognomist and theologian well-known in England, Germany, and France for his so-called scientific book, Fragmente zur Beförderung der Menschenkenntnis und Menschenliebe, which was originally published between 1775 and 1778. He believed that physiognomy related to specific character traits in people. He illustrated this theory through a series of profile portraits to demonstrate how moral character could be discerned through an analysis of “lines of countenance.”

Both Duranty and Degas had devised a response to theories of expression and character, including Lavater’s analysis of human countenance and how it expressed emotion. Degas’s musings on physiognomy explain the importance of his portraits of the person’s gestures, physiognomy, and individualized emotions.

Degas rejected Lavater’s formulaic attempt at the assessment of moral character. His approach was more nuanced, a quest for truth in portraiture that rose above typological representation.

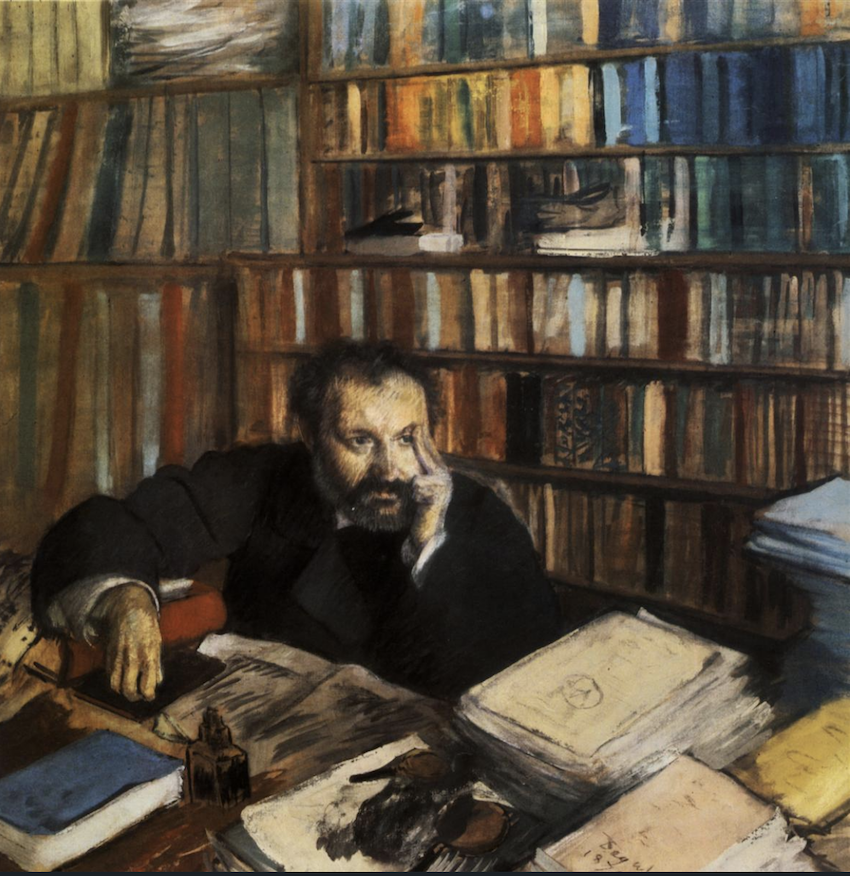

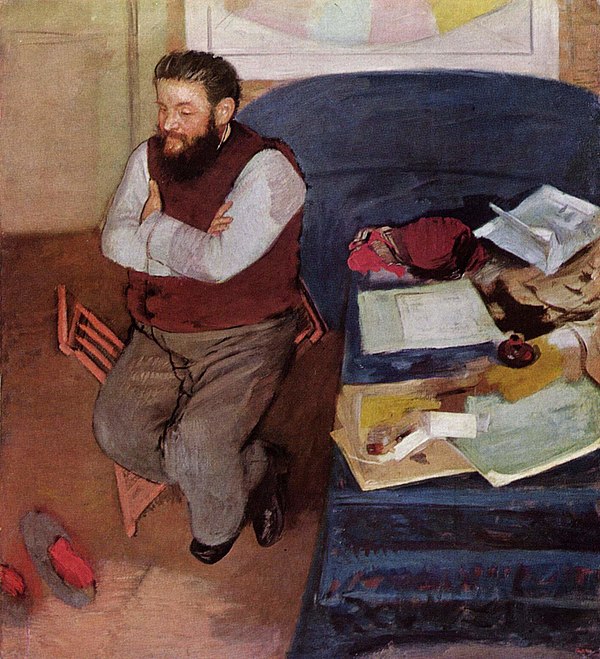

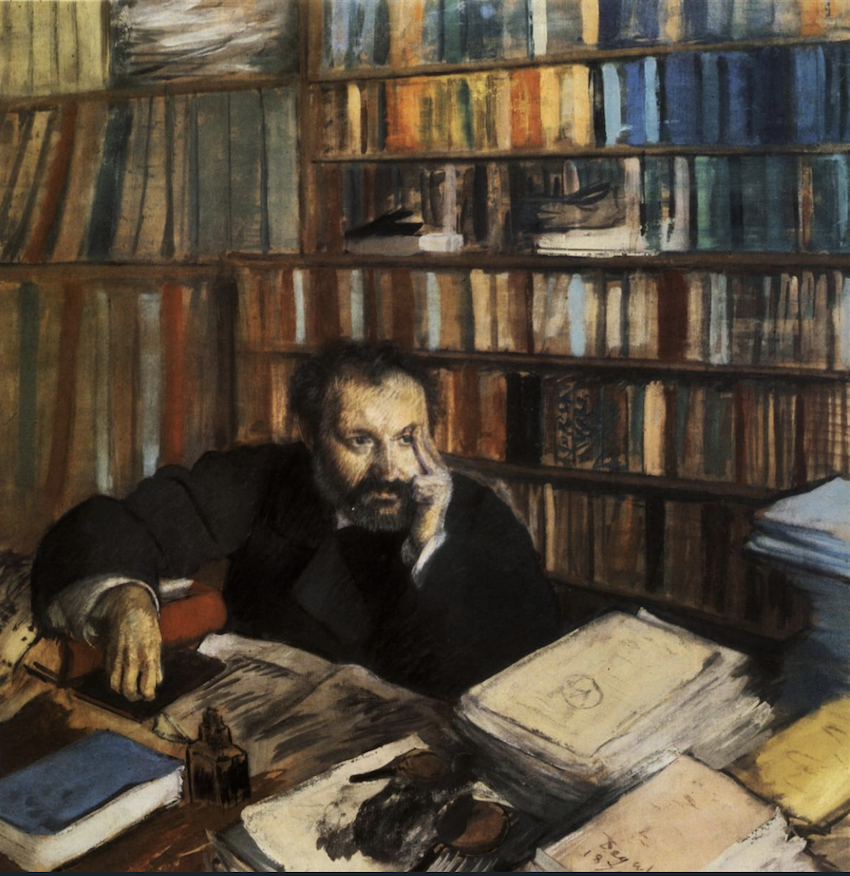

He looked for subtle but incisive deviances within physiognomic and social typologies, insisting that modern individualism was located within these aberrations. The result is exemplified in two portraits of novelists and critics; Edmond Duranty, a firm supporter of Realism and Impressionism in France, and Diego Martelli, one of the earliest advocates of Impressionism in Italy.

Degas’s portraits of Martelli and Duranty each portray a modern intellectual in situ, conveying their uniqueness through the keen manipulation of stylistic devices and attention to particularized elements within their overall settings.

The use of arbitrary vantage points and cropping images, was a direct influence of photography, allowing Degas to freeze frame a particularly interesting viewpoint which would otherwise be passed over. In Diego Martelli, the figure is portrayed from an elevated perspective. This vantage point, unusual in real life but appearing completely natural here, was calculated to emphasize Martelli’s squat stature and rounded contours. The pose and perspective, evoke a sense of comfortable informality. He is a typical “endomorph,” as defined by William Sheldon, correlating physiological and psychological characteristics in Atlas of Men: A Guide for Somatotyping the Adult Male at All Ages (1954). Sheldon, an American psychologist and physician, believed that the psychological makeup of humans had biological foundations. He classified people according to body types or somatotypes. The endomorph, he maintained, had a “viscerotonic” personality – composed, amiable and comfortable – which directly correlated with a rounded and soft body.

How Degas portrays Martelli suggests the man’s contemplative, unconfrontational nature. His arms are folded across his chest and supported by his ample belly, and his plump legs, crossed and tucked under his body, strain against the cloth of his trousers. His weight is emphasized by the artist’s over-view and the spindly appearance of the folding stool he sits on. Papers and paraphernalia lie haphazardly on the table in the foreground while a pair of red-lined carpet slippers flop by his feet. The sofa’s rounded back echoes the rounded contour of the image on the wall and the outlines of Martelli’s plump body.

Degas’s portrait of Edmond Duranty is almost entirely comprised of books. They are laid out horizontally on crowded bookshelves and piled up in diagonals on the desk in the foreground. Duranty himself sits pensively in the centre of it all, his hand pressed against his eyelid in a gesture of pure concentration. The portrait is neither painstakingly descriptive nor idealizing, but it captures the author authentically in his own environment at a particular moment in time.

Duranty is observed from an elevated vantage point, which furthers the sense of his fusion with his surroundings. There is a dynamic quality to the delineation of the pictorial elements, which is echoed in the dry, elegant energy of the pastel and gouache mediums.

While both portraits date from the same period and both men share the same profession, they do not conform to a specific genre. On the contrary, their uniqueness and difference are given visual priority.

Degas’s portraits of female figures fall within the large number of works he produced of women, over half of his oeuvre, although substantially fewer single portraits exist than group portraits.

Between 1853 and 1873, Degas’s focus was predominantly on portraiture. His portrait of Victoria Dubourg, a contemporary still-life painter who would later wed Henri Fantin-Latour exemplifies his early interest in capturing his subjects in their circumstances by paying attention to background settings.

Here, Degas does not explicitly refer to Dubourg as a painter by placing her in a studio setting. But she is shown leaning forward, entering the viewers’ space and holding their gaze. Centrally positioned, she conveys assertiveness, alertness, and intelligence. Her hands are a central focal point of the composition, communicating her craft and artistic competence. The mantelpiece to her left holds flowers in a vase, the spray of green stems mirroring the green ribbon around her neck. The flower arrangement hints at the art practice of Dubourg, as does the empty chair, which may suggest the absent presence of her fiancé and painting collaborator, Fantin-Latour.

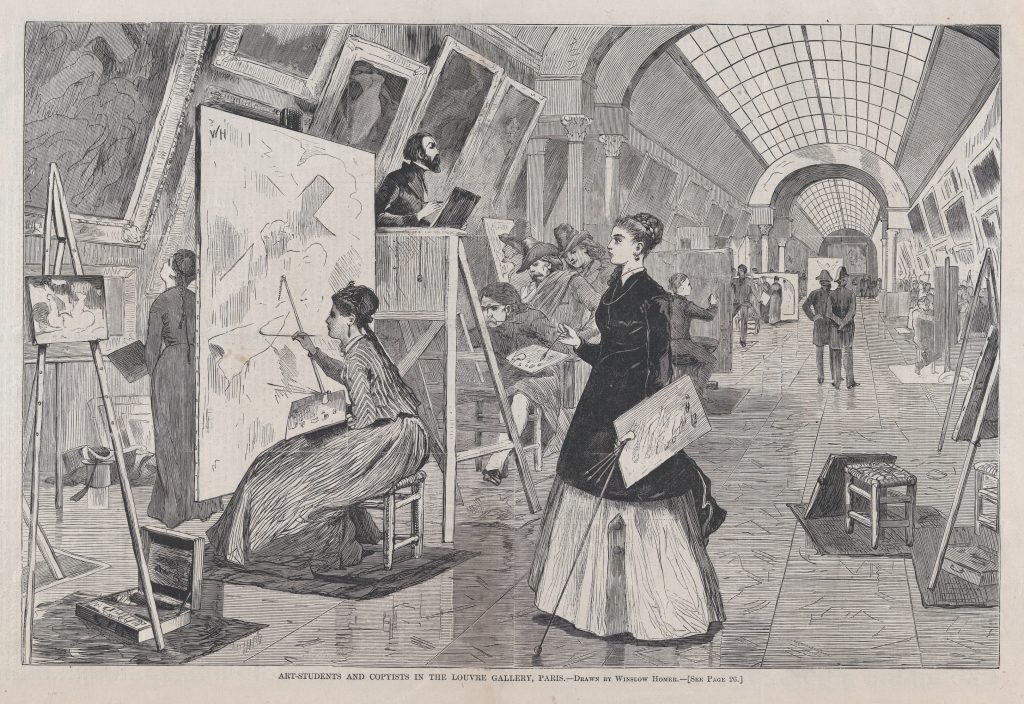

Isabella Holland, curatorial assistant of European paintings at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, provides the following brief introduction to this little-known woman artist (https://legionofhonor.famsf.org/blog/Victoria-Dubourg-and-the-Louvre):

Dubourg trained privately in the studio of artist Fanny Chéron and established her independent practice in Paris by the early 1860s. Archival records place Dubourg at the Louvre in 1866, when she received an 800 franc commission from the Ministry of Fine Arts to execute a replica of Pietro da Cortona’s 17th-century painting Virgin and Child with Saint Martina. This assignment coincided with an extensive arts initiative undertaken during the reign of Napoleon III to expand and reorganize the Louvre’s collection. As part of the state’s oversight, the institution’s holdings were copied and sent to churches and administrative offices throughout the country. Dubourg later fulfilled a similar request to copy Titian’s Pilgrims of Emmaus, no doubt granting her some financial independence to study and copy artworks in the Louvre’s collection for her own personal development.

For female artists who were barred from attending the École des Beaux-Arts until 1897, studying at the Louvre provided access to the art world and opportunities to form connections with other artists. Dubourg met Fantin-Latour, while they copied Correggio’s The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria at the Louvre in 1869. Both artists socialized with a circle of progressive artists who frequented the museum, including Édouard Manet, a guest at their wedding in 1875, Berthe Morisot, and Edgar Degas.

An example of the pair’s interest in Chardin may be found in Victoria Dubourg, Fantin-Latour, Still Life with Pink and White Stock, in which a simple, frothy arrangement of garden flowers seems to float out from a sombre background.

As collaborators, Dubourg and Fantin-Latour produced some of the most important flower painters of the later part of the 19th century, despite having a well-documented interest in religious painting from the Italian Renaissance.

The artists’ attraction to still-life painting, particularly works by the 18th-century still-life painter Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin, paralleled the genre’s resurgence throughout the 1850s and 1860s.

Dubourg and Fantin-Latour shared studio space at 8 Rue des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Their interest in floral still-life was facilitated by their access to fresh blooms to paint from an inherited family estate in Buré, Normandy. Dubourg and Fantin-Latour developed a similar style from working side by side, and a comprehensive understanding of Dubourg’s practice remains unrealized; her biography has been limited to the events around her marital relationship. Holland writes, “Dubourg signed the prodigious number of pictures she displayed at the annual Paris Salon and other international art exhibitions with her maiden name, perhaps in an effort to hold on to a discrete artistic identity.”

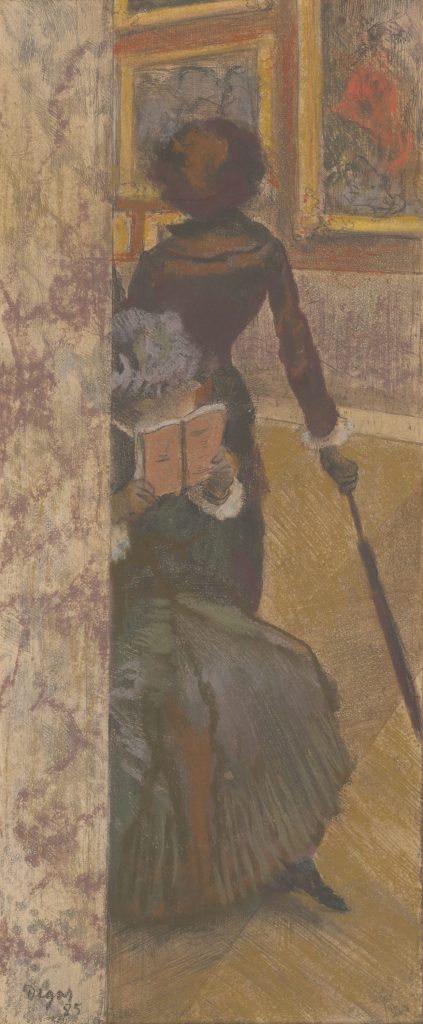

Degas’s images of his friend and fellow artist Mary Cassatt are strikingly different from his representation of Dubourg. In Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Etruscan Gallery, a pictorial informality initially masks the wealth of information contained within the work. Degas’s understanding of body language inspires a work that communicates the female artist’s mood even though her back is turned to the viewer.

Degas sought to call attention to Cassatt as a practicing artist out and about in the world, and to capture her critical eye. While her face is not visible, Degas achieves his objective through the subtle juts and angles of her stance as she examines the artworks on view at the Louvre. Her posture is distinctly different from that of her sister Lydia who is seated as she half-heartedly glances at the display of artifacts.

In 2014, a Degas/Cassatt exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington included a number of Degas’s works depicting Mary Cassatt at the Louvre. It was accompanied by the following online text (https://www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/exhibitions/pdfs/2014/degas-cassatt-brochure.pdf):

Cassatt once remarked that she posed for Degas “only once in a while when he finds the movement difficult and the model cannot seem to get his idea.” Yet the theme of Cassatt strolling through the Louvre clearly fascinated him, resulting in a rich body of work produced in a range of media over a number of years.

Encompassing two prints, at least five drawings, a half-dozen pastels, and two paintings, the series marks one of Degas’s most intense and sustained meditations upon a single motif.

Degas’s choice of the Louvre as the setting for this group of works spoke to the two friends’ mutual appreciation for art and its tradition. In the series, he depicted Cassatt as an elegantly dressed museum goer, wholly absorbed in her study of art. Nearby, a seated companion (usually identified as Cassatt’s sister Lydia) looks up from her guidebook. Cassatt, with her back turned fully to the viewer, balances against an umbrella in a pose that highlights the curve of her body and underscores her air of assurance. Although the precise relationship between the various works is not entirely certain, Degas most likely began with drawings and pastels of individual figures that served as references for the series as a whole.

Degas’s portraits of Cassatt visiting the Louvre speak to the experience of an artist’s appreciation of fine art. With his portrait of Madame Camus, Degas extends the thematic allusion to a musician’s pleasure in music.

Madame Camus was the wife of Degas’s physician and a highly regarded pianist. In this portrait, she is shown dressed in a gown of rich red, holding a large fan and gazing intently into the distance. Her engaged attention is aural, however, not visual. Degas’s synaesthetic suggestion of a sensuous, enveloping musical experience is rendered through the play of formal elements: the atmospheric treatment of the space, the deep palette, and the rhythmic articulation of forms and contours.

Degas used the technique of chiaroscuro, balancing the strong contrast of light and shade to create his dramatic effect. More importantly, he achieves this impression while also capturing the very essence of Mme Camus.

When Madame Camus was exhibited in the Salon of 1870, it was praised by Théodore Duret, the journalist, author and art critic, whose Critique d’Avant Garde (Paris, 1885), written in support of the Impressionists, was among his best-known works. He described the painting in the Electeur Libre (2 June 1870) as a “picture that escapes from the well-trodden ways…the lady in the picture…is a credible, a real, very alive, very feminine, very Parisian.”

Years later, in her recollections, Jeanne Raunay, a French mezzo-soprano opera singer, described Mme Camus as a beautiful young woman, her “eyes charged with languour and wit, which she barely opened, letting their fire gently pass through half-closed eyelids, and her complexion and hair were dream-like” (“Degas, souvenirs anecdotiques,” La Revue de France, March 15, 1931: 213-321, and April 11931: 619-32).

Comparing the preliminary drawing Madame Camus with a Fan with the completed painting reveals how Degas transformed the picture in charcoal and pencil into a fully realized composition that effectively describes the character and mood of his subject.

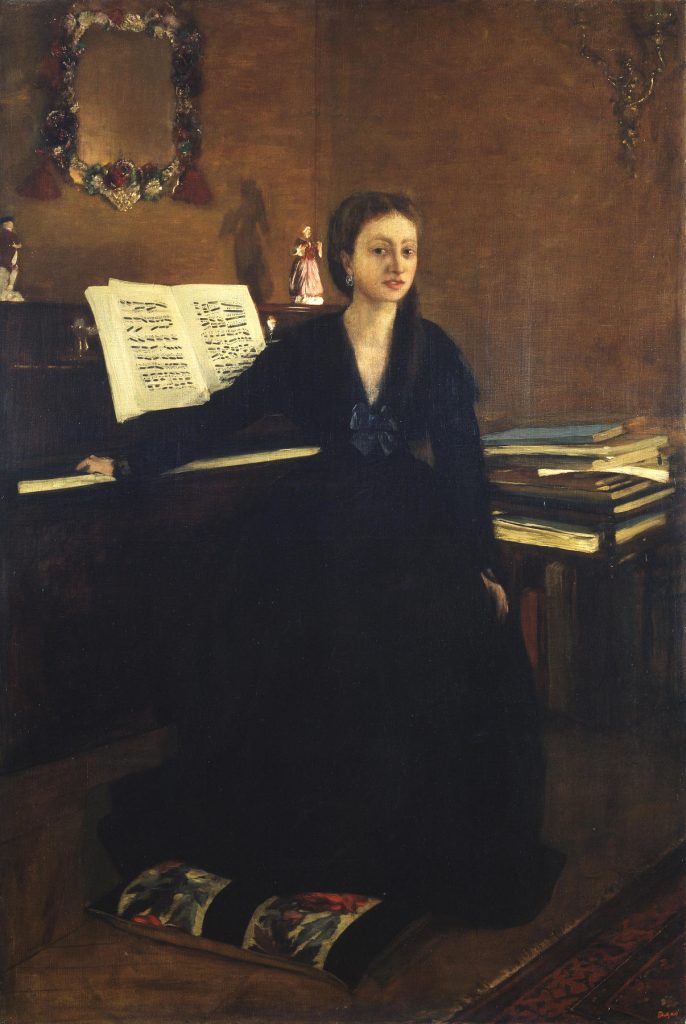

Degas painted another portrait of Mme Camus during the same period. This time the piano, the instrument she excelled at, is an integral part of the composition, symbolizing her active engagement with music and her identity as a performer.

Much has been made of how differently male and female sitters were represented in Impressionist portraiture. And while differences do exist, they are reflective of the markedly different lived realities of males and females. Social customs governed behaviour and appearance, and it is unsurprising to see such strictures represented in paintings. Impressionist portraiture, however, frequently challenged gender-based stereotypes in subtle ways.

If passively listening to music, for example, was stereotypically a female experience, then portraying a man doing so was a means by which to sabotage this ascribed meaning.

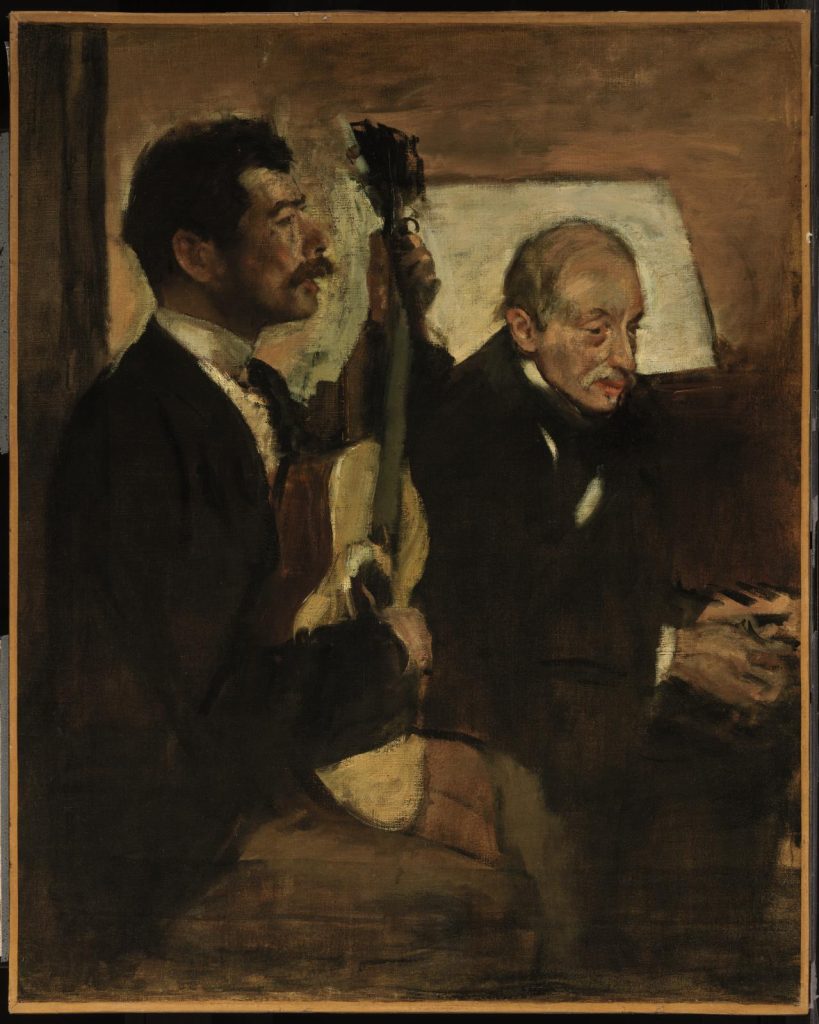

Degas engaged with this trope on several occasions. For example, he portrayed his father listening to the singer Pagans more than once.

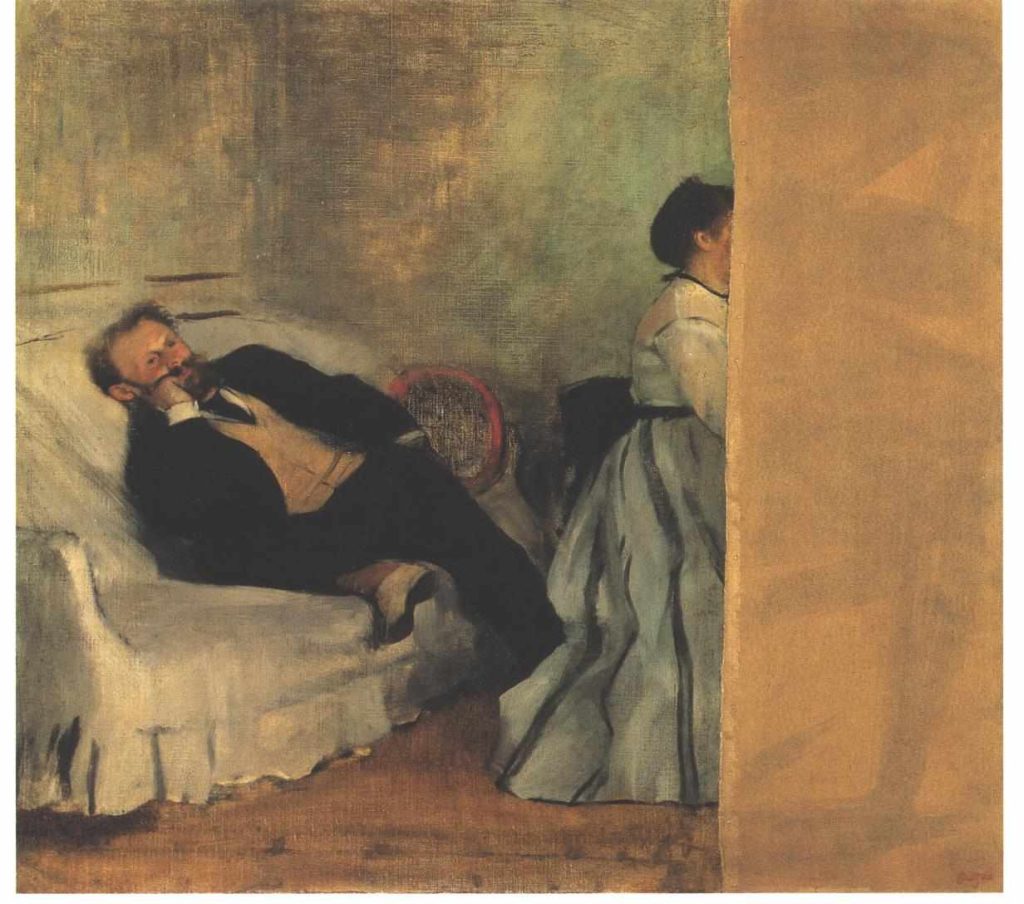

The painting Edouard Manet and his Wife also reflects his interest in the theme. It is a double portrait of Manet and Suzanne which shows the artist reclining on a sofa, intently listening to his wife playing the piano. Besides his suited figure, there is little attempt at conveying his social and artistic status or his reputation as a dandy. The pose is unflattering; Manet is sprawled out in a way that emphasizes his stockiness, a foot drawn up beneath his body. While he is leaning back, there is a deliberate sense of connection between the two figures whose garments extend one into the other. However, we cannot discern much more about Mme Manet as the entire front portion of her body was cut away by Manet, who felt that Degas had distorted his wife’s features.

Degas reclaimed the work to restore Suzanne’s likeness but never did. He kept the vandalized painting on his wall, as is visible in a photo of his apartment taken around 1895, now in the Bibliotheque Nationale de Paris.

Degas’s ability to employ formal dynamics to convey individuality, or alter an individual’s perception, is clearly at work in Hélène Rouart in her Father’s Study. The young woman, ill at ease in her surroundings, appears physically and emotionally trapped in her father’s study. She is hemmed in by paintings on one side and sculptures on the other, an empty chair pressing against her front. She is literally and figuratively out of her element, her industrialist father being the actual subject in absentia.

Hélène’s father was an engineer, industrialist, amateur painter and friend of Degas. In his portrait Henri Rouart in front of his Factory, Degas utilizes the affectation of the portrait d’apparat—a device of incorporating symbolic objects in portraiture—to underscore Rouart’s status as a wealthy industrialist. He is solemn and regal as he stands in front of one of his factories. He is dressed smartly and wears a top hat. The heavily smoking smokestacks and the railroad lines zooming into the canvas and converging just behind his head infer the connection between his intellectual acumen and his success.

Was Hélène an unhappy daughter, burdened by her successful father and possibly relegated to the role of office secretary and clerk, attending to the considerable paperwork of her father’s enterprises?

Jonathan Jones, the British art critic for The Guardian (June 24, 2000, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2000/jun/24/art), sees her this way:

Hélène is a strange portrait. It is supposed to be of Hélène Rouart, but she is utterly overwhelmed by signs of her father. She stands in his study surrounded by his art collection, posing behind his chair, which is colossal compared with her, as if behind a restraining fence. She is diminished by the imagined presence of her father, who might be just outside the room – though actually he was travelling in Venice when this was painted.

Hélène has a pasty complexion, her hair is flattened, her dress encases her. She lists like a passenger on a swaying deck. This is the ailing, unhappy daughter of a 19th-century patriarch, so subjugated to the fetishised, massive presence of her father – images of his taste, his wealth – that she seems half-dead. To her left is a landscape of Naples by Corot, and lower down a drawing by Millet, and she is juxtaposed with them as another of her father’s treasures. To her right is the glass case containing her father’s collection of Egyptian funerary artefacts. She too is mummified and entombed in this room. Degas makes Hélène show the ringless fingers of her left hand. The only man in her life, this painting says in a brutal way, is her father.

…What a fall to earth is in this painting. Hélène Rouart, the well-behaved daughter of the bourgeoisie, is repressed, dulled in a way that Degas’s proletarian performers are not. She’s painted to make her as lifeless as possible: her hands drape weakly over the chair back, her face is passionless. This is middle-class depression, the crisis of the 19th-century individual that Freud would later diagnose. But it would not be true to say there’s no desire in this painting. It is unbelievably luxurious: Degas kept repainting and retouching it over many years, making the reds ever richer, the texture more opulent. The sexuality that is absent from Hélène’s demeanour becomes the glint of silver on the mummies’ vitrine, the luxury of a Chinese silk hanging. The painting is suspenseful: possibilities, unacknowledged desires, circulate in its tense space, between the painter, the young woman and her father.

Hélène Rouart married and left home soon after posing for Degas. As for Degas, he died 30 years later with this canvas still in his studio.

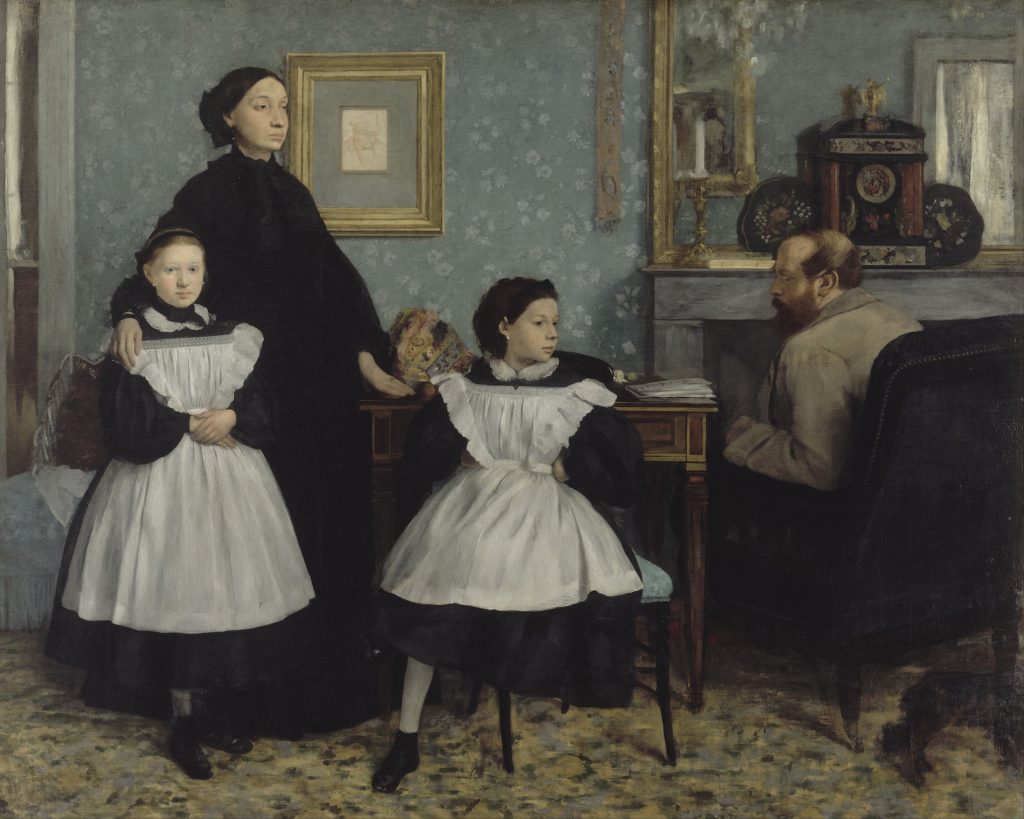

Degas was always sensitive to family dynamics, relationships that shape individuals and the contributing factors that inform those relationships. The Bellelli Family is an early work begun during a stay in Italy. It shows his paternal aunt Laure, her husband, Gennaro Bellelli, and their two daughters, Giovanna and Guilia. At first glance, it appears to be a conventional, finely painted and well-composed family portrait.

Jean S. Boggs describes the interior setting in “Edgar Degas and the Bellellis” (Art Bulletin 37, no. 2 (June 1955): 127-136):

Here is a dignified middle-class family, virtuously in mourning [in I864 the baron Bellelli died] painted in its drawing room. A dog, a newspaper, a basket of mending and a bassinet further testify to respectability. Even the scale of painting, so large that the figures are approximately life-size is somehow reassuring. We are ready to be enchanted with the ingredients of the setting, lovingly to absorb the candles, the clock, the books on the mantelpiece; the painting, open door and chandelier, reflected in the mirror; and the soft blue wallpaper, the bell-pull and the chalk portrait of Degas’s father on the wall; prosaic details out of which the painter created the atmosphere of a bourgeois living room. The light also carries us dreamily back to the past. It is dappled by the flowered wallpaper, the spotted rug and the broken reflections of the mirror. Most of it comes from one source: the open door we can see in the mirror. Where it does not penetrate, on the upper part of the wall, in the left hand corner of the room under the furniture, there are dusky shadows, which make it more positive still. However, it always remains the quiet light of a dimly lit room, a room seemingly remembered from our nineteenth-century past.

That being said, the monumental Portrait de famille, as it was called when it was first exhibited at the Salon of 1867, is a depiction of a family drama. The painting highlights the mother’s stature: she stands straight and dignified, while the father is seated inward-facing on the other side of the room.

Mother and daughters are in dark clothing, alluding to the recent death of the Baroness’s father. On the wall hangs a small portrait of him by Degas (a nod to the aristocratic tradition of portraiture), underscoring his presence in the scene and reinforcing the heavy atmosphere.

Degas was undoubtedly aware of the strains between Gennaro Bellelli and his wife and the tensions at play while painting the family portrait. However, his ambition was to create a significant painting which captures, in the words of the French painter, art critic and museum curator Paul Jamot “his taste for domestic drama, a tendency to discover hidden bitterness in the relationships between individuals…. even when they seem to be presented merely as figures in a portrait.” (Paul Jamot, Degas (XIX Siecle) (Geneva: Editions d’Art Albert Skira, 1947)

That he successfully portrayed the disequilibrium through pictorial means without compromising a superficial reading of a family scene is laudable. In fact, the insertion of signs of dissension and instability rendered the portrait more interesting.

In pictorial terms, the tensions are not confined to the postures of the father and mother, one slouched in a seat, the other standing overly erect, but also by the figure that both separates and connects them, the awkwardly posed Giulia pictured between them. In addition, the small dog seen moving out of the picture plane on the right creates further fragmentation. With a wave of its fluffy tail and a kind of cheeky je m’en foutisme (I don’t-give-a-damn attitude) that is entirely at odds with the seriousness of the painting, the dog works to undermine the solemn balance and traditional formality of Degas’s monumental and tensely harmonized family-group structure.

Thus, Degas offers a contra version of a conventional bourgeois domestic scene, as much about the contradictions inherent in the idea of a bourgeois family in the middle of the 19th century as it was a family portrait.

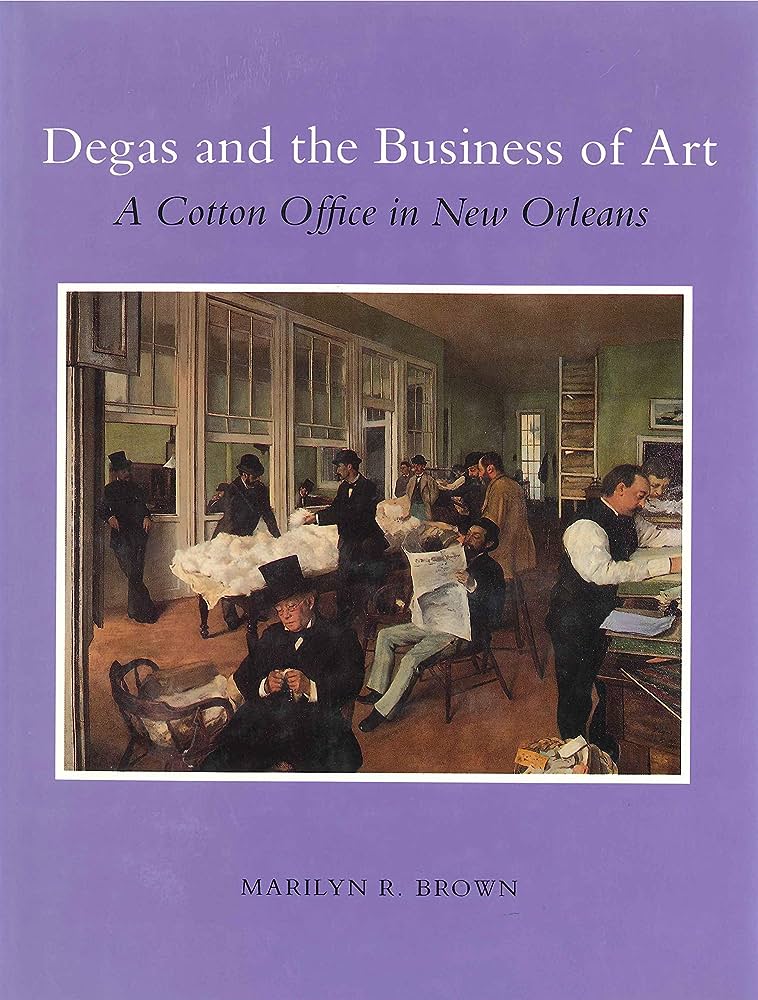

In October 1872, Degas travelled to New Orleans, where he stayed for five months with his late mother’s brother Michel Musson and the extended Musson family at 2306 Esplanade Avenue. The artist’s younger brothers, René and Achille, were by then settled in the United States, running a wine importation business financed by the Parisian Degas family bank. From the second-floor front gallery of the house on Esplanade, Degas painted A Cotton Office in New Orleans, an image of the office of Musson’s factorage firm at what is now 407 Carondelet Street. A Cotton Office in New Orleans stands as both a family portrait and a portrait of the new universe of American commerce.

In the foreground, Degas portrays top-hatted broker Michel Musson carefully examining a fibre sample between his thumb and forefinger. Degas’s brother René is seated reading the Daily Picayune, and his cousin Achille looks over at the accountants as he lounges against a window. Prominently posed at the front is the cashier John Livaudais standing over a large register. Degas has captured the characteristic disposition of each of the men in the office in myriad small details while effectively conveying the atmosphere of places of business such as the cotton office.

Degas’s A Cotton Office in New Orleans (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994) by Marilyn R. Brown is an important portrayal of nineteenth-century capitalism that explores the artist’s complicated relationship to the art business.

Jerah Johnson’s book review, “Degas and the Business of Art: A Cotton Office in New Orleans by Marilyn R. Brown” considers Brown’s historical description of the painting (Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 36, no. 3 (Summer 1995): 345-347):

Degas himself noted that his painting was “Louisiana art” not “Parisian art” and that it was “a picture of the local vintage, if there ever was one.” The languor of the cotton office Degas depicted — of the fourteen figures in the painting, only half are, in Degas’s own words, even “more or less busy”— suggests the oppressive heat and slow pace of life in New Orleans. Some critics have argued, Brown reports, that the general inactivity in the office also implies a contrast to the hustle and bustle of the New Orleans Cotton Exchange, which had been established around the corner on Gravier Street only two years before and which was rapidly putting old-fashioned factors such as Mussonout of business. Musson’s firm, in fact, went bankrupt while Degas was painting the picture.

Degas designed the Cotton Office with a particular buyer in mind, an English textile magnate and art collector in Manchester. But Degas’s agent could not negotiate the Manchester sale, so Degas put the Cotton Office in the second Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1876. The piece got a mixed critical reception that, on balance, represented a qualified success, particularly with politically right-wing critics, who liked both the bourgeois subject and the traditional surface finish of the picture, so unlike the finish of Degas’s more ‘modern’ works. But no one offered to buy it. Needing money badly and desperate to sell his cotton, as he now called the piece, Degas had his dealer send it to Pau for exhibition in 1877-78. Pau was an old textile manufacturing center in remote southwestern France, a sort of minor Manchester, but with some important differences. It had a museum that was closely associated with a local Society of the Friends of Art, the membership of which included the town’s political, banking, and manufacturing elite. The Society was one of the most active, successful, and progressive of France’s many provincial friends-of-art associations, all of which had developed connections with Paris dealers and agents. And Pau had also become a winter resort for large numbers of rich Americans.

…It was the ideal market for Degas’s cotton, and the Pau museum bought his piece when the 1878 exhibit closed. It was not only the first of Degas’s paintings purchased by a museum, but the first painting by any member of the Impressionist group purchased by a museum. Thus the sale marked turning points in both Degas’s career and in the Impressionist movement as a whole. And it exemplified, as well as anything could, the new business of art.

Two years later, Degas decided to embark on another atypical family portrait set within a remarkably strikingly unusual perspectival space. In Place de la Concorde, Vicomte Ludovic-Napoleon Lepic, aristocrat, artist, museum curator and père de famille, is depicted in the extreme foreground as he strolls across the Place de la Concorde, top hat set at a jaunty angle, cigar thrust between his lips and a furled umbrella tucked beneath his arm. He is accompanied by his two young, fashionably dressed daughters, Eylau and Janine, and their well-bred borzoi, Albrecht.

Place is virtually unpopulated otherwise, with just a few small figures in the background and a marginally placed figure at the left. This is Degas’s friend Ludovic Halévy, well-dressed and carrying a walking stick. His role as a bystander, rather than a subject, is further stressed in how he is pictured turning to take in the group.

The family easily dominates the picture plane’s expanse, alluding to Lepic’s equally prominent and privileged position in the heart of urban Paris. The space is near empty, alluding to the influence of photographic aesthetics in the vastness of the negative space, the cropping of the composition and the overall random quality of the event.

Nancy Forgione in “Everyday Life in Motion: The Art of Walking in Late-Nineteenth-Century Paris” (Art Bulletin 87, no. 4 (December 2005): 664-687) connects photographs of people walking in Paris with Degas’s painting of the Lepic family:

Interest in the analysis of physical movement grew rapidly during the nineteenth century, encouraged and aided by the new medium of photography. Though, initially, lengthy exposure times meant that moving objects were precisely what photography left out, within a few short years the documentation of movement became one of its most impressive accomplishments.

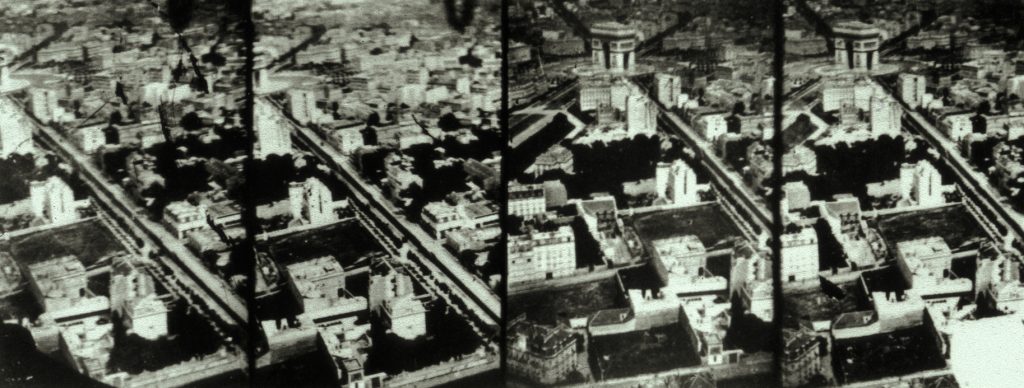

For example, in this stereograph photograph two nearly identical photographs or photomechanical prints are paired to produce the illusion of a single three-dimensional image.

The photographic image was usually viewed through a stereoscope, such as the “Brewster” pictured above.

Pedestrian street scenes such as Hippolyte Jouvin’s The Pont Neuf Paris were influential during the 1860s and 70s because they were the best way to analyze actions such as walking or running. This new visible record of knowledge informed how paintings were made and how people appeared to move in space. Looking at Place de la Concorde, for example, we comprehend that the central figures in the square have just stopped walking. We know this even though the image is cut off, and their lower bodies are not visible. Forgione describes the painting in this way: