Chapter One

GUSTAVE COURBET &

Revolutionary Realism

CONTENTS

Introduction

1.1

1.2

Capturing Contemporary History: The Artist as Witness

1.3

Caricature and Social Critique

1.4

Realism and the Democratization of Art

1.5

Radical Realists: The Advent of the Avant-Garde

1.6

Gustave Courbet and the Paris Salon

1.7

Painting Ordinary People: Elevating the Humble Hero

1.8

A Class in Transition: Courbet’s Young Ladies

1.9

Art, Patronage, and the Outsider Artist

1.10

INTRODUCTION

The Realist Movement in France embodied the aspirations of the cultural avant-garde during a period marked by social, political, and economic upheaval. In the mid-nineteenth century, a demand for revolutionary change in art, paralleling the calls for reform in literature, resonated with the broader movement for democratic change in modern Europe. Radical thinkers in France championed sincerity in art and advocated for thematic content that authentically reflected the realities of contemporary life. The Realist Movement, thus, emerged as a response to the prevailing sentiment that art should engage with and depict the genuine experiences of the time.

Realism gained ground during the French Second Empire as a politically motivated art movement. It rejected Romanticism’s irrelevant subjects, all things exotic and imaginary, and a sensorial aesthetic meant to visually entice. Instead, Realist artists sought out the commonplace and contemporary, real people and events painted in shockingly unembellished terms. Just as literary figures like Émile Zola and Honoré de Balzac fictionalized urban workers and the rural poor, painters eschewed history’s grand narratives and personages to make heroes of ordinary women and men.

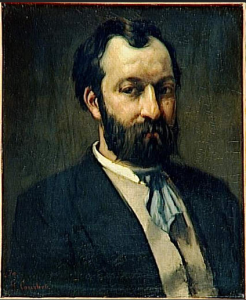

Gustave Courbet, a painter and provocateur, played a pivotal role in spearheading French Realism. As a self-proclaimed ‘avant-gardist,’ he boldly flouted academic conventions and challenged traditional rules of artistic representation. Aligned with socialist ideology, Courbet fervently advocated for the democratization of art, aiming to make it more inclusive and accessible to the working proletariat.

1.1

| Revolution and Reform

The revolutions of 1848 were a series of widespread republican rebellions throughout Europe. Democratic and liberal in concept, these uprisings were attempts at overthrowing monarchical systems of governance and replacing them with elected nation-states. Beginning in France with the February Revolution of 1848, political upheaval spread rapidly across fifty countries. The dissenting movements generally consisted of temporary coalitions of reformers, labourers and middle-class agitators. Although many revolutions were suppressed and short-lived, they had important political ramifications. Probably the most significant of these was the dismantling of France’s July Monarchy and the proclamation of the Second Republic.

Louis-Philippe I ruled as the “King of the French,” rejecting the pageantry of the Bourbons and introducing broad-based reforms during his early reign. These included religious equality for Catholics and Protestants, electoral reforms, the re-establishment of the National Guard to empower citizens, and his government’s adherence to a politically motivated juste milieu. By 1840, however, the regime had settled into static stability. The result was that actual power was in the hands of the wealthy who were elevated socially by industrialization.

In The Class Struggles in France, 1848-1850, articles written by Karl Marx for the newspaper Neue Rheinische Zeitung in 1850, collated and republished as a book in 1895 by Friedrich Engels, Marx writes:

After the July revolution, when the liberal banker, Lafitte, conducted his compeer, the Duke of Orleans, in triumph to the Hotel de Ville, the former uttered the words: ‘From now on the bankers will rule.’ Lafitte had revealed the secret of the revolution. Not the French bourgeoisie ruled under Louis-Philippe, but only a faction of the same, bankers, kings of the stock exchange, railroad kings, owners of coal and iron mines and of forests, a part of the land-owning element allied with them—the so-called aristocracy of finance. It sat upon the throne, dictated laws to the Chambers and handed out the political jobs from the Ministry down to the Tobacco Bureau.

Marx, a German radical political and economic philosopher and theorist with contributions from his friend and collaborator Friedrich Engels, wrote The Communist Manifesto (1848), a pamphlet that succinctly described their theory of historical materialism and predicted the overthrow of capitalism by the industrial proletariat.

The July Monarchy was a regime with which the urban workers were profoundly dissatisfied, moved by their misery and the haunting promise of social equality that was instilled by the French Revolution of 1789. This segment of society perceived government policies as veiled attempts to reinforce their power and influence. Other factors, too, exacerbated their discontent. In 1846 a crop failure quickly developed into a full-scale economic crisis: food became scarce and expensive, many businesses went bankrupt, and unemployment rose. There were signs of moral crisis within the governing elite: scandals that implicated some high officials of the regime and growing dissension among the notables.

Along with this was a severe alienation of many intellectuals. For a decade or more, the French proletariat and the middle class had been increasingly drawn toward socialist politics in their various utopian forms. The years 1830 to 1848 were marked by an unprecedented flowering of socialist thought that called for changes that would promote equality and empower a broader constituency of the French population. Fuelled by this rhetoric, a democratic revolution led by the bourgeois population erupted in February of 1848. The upheaval resulted in the Monarchy’s overthrow and the proclamation of a French Republic.

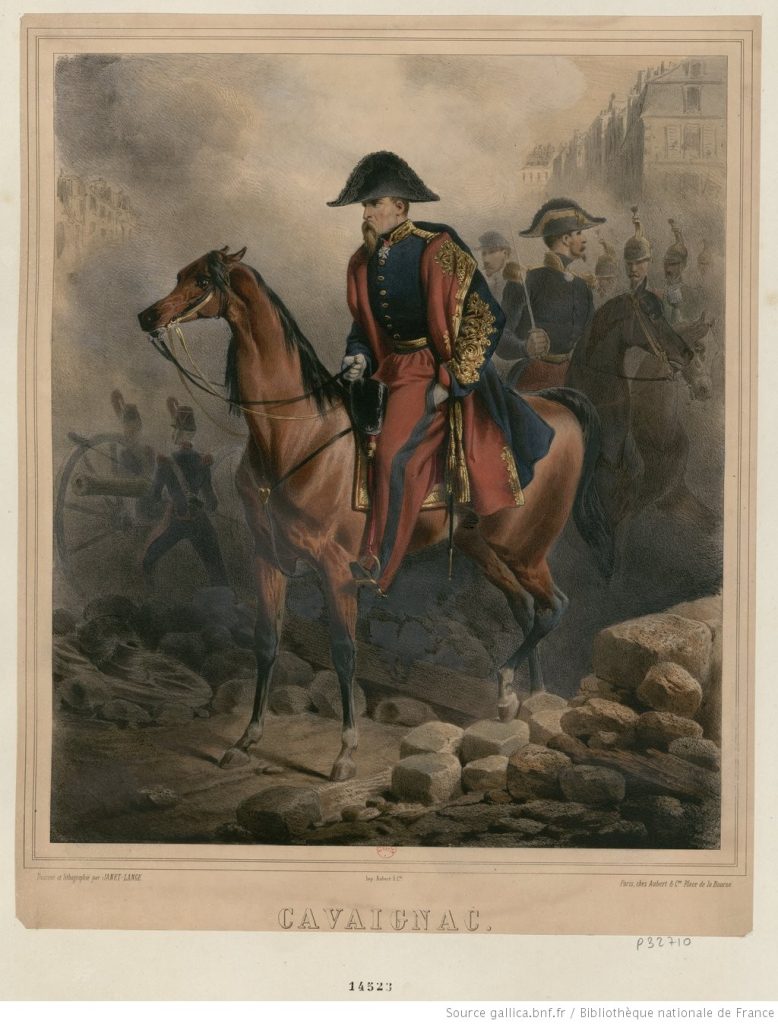

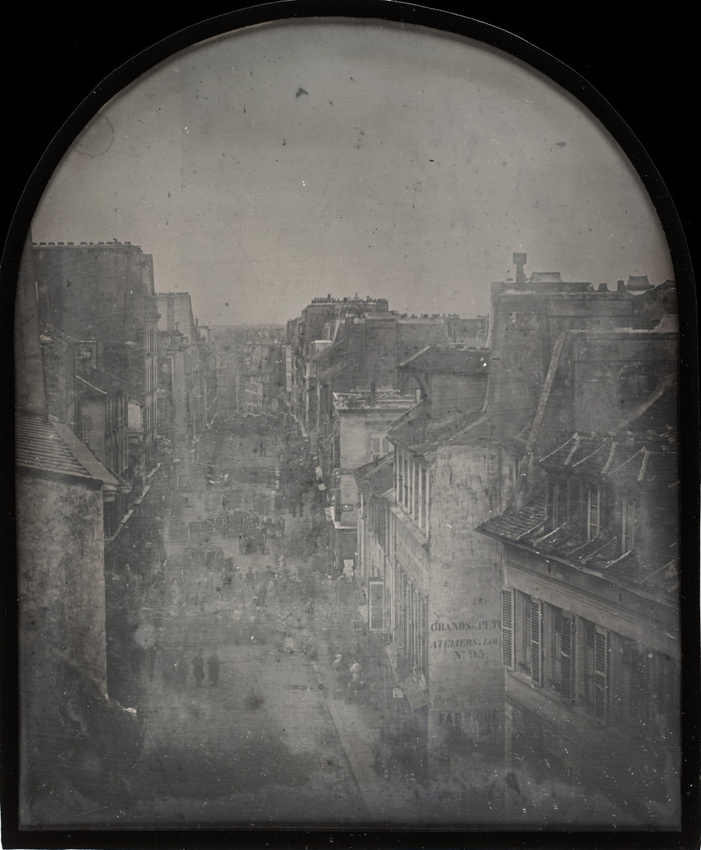

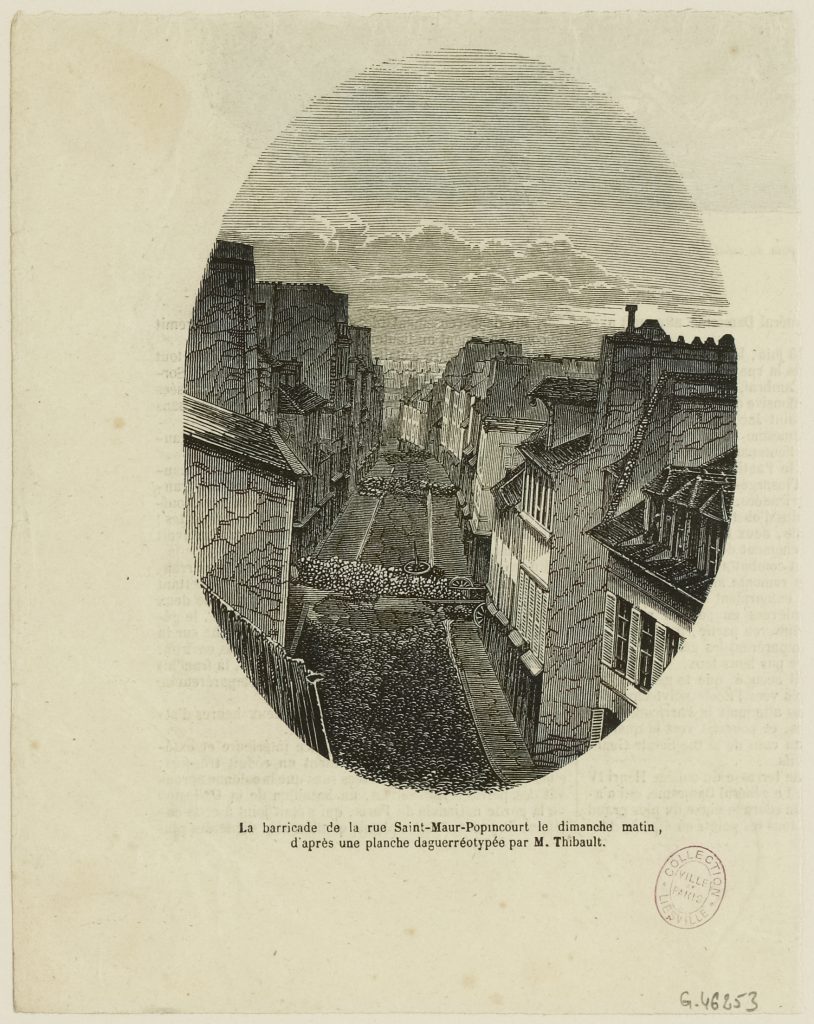

By June 1848, the makeshift improvements to the conditions of Paris workers were so negated by the government’s right-leaning policies that full-scale fighting broke out in the working districts. The immediate consequence was a brief and bloody civil war in Paris, the so-called June Days (June 23–26, 1848). Thousands of workers suddenly cut off from the state payroll, were joined by sympathizers—students, artisans, and employed workers—in a spontaneous protest movement which led to intense confrontation between the protestors and the National Guard. As the altercation progressed, the insurgents erected makeshift barricades in the streets and armed themselves with weapons they seized in the armouries.

The pair of daguerreotypes above, showing the revolutionaries’ barricades on the rue Saint-Maur before and after the army’s attacks, circulated widely as woodcut engravings in L’Illustration—a French newspaper. As such, they were among the earliest photo-based newspaper illustrations. It wasn’t until the widespread implementation of the halftone printing process in the 1880s that photographs could be faithfully reproduced in the press.

1.2

| Capturing Contemporary History: The Artist as Witness

During and after 1848, artists and intellectuals in France were compelled to address the alarming events they witnessed. Many believed that regardless of the immediate outcome of the June Days insurrection, a new stage in social politics had been reached in which circumstances pressed working-class people to forge alliances to defend their opinions. These increasingly mobilized groups advocated for a radical restructuring not just of single policies or governments but of society itself. Artists played an important role in this widespread cultural shift.

The French Classicist painter Ernest Meissonier (1815–1891) was a National Guard artillery captain during the June Days. Traditionally a middle-class body, the Guard now allied itself with the Republican revolutionaries—a change in allegiance which reflected a general erosion in the popularity of Louis-Philippe and his “Bourgeois Monarchy” rather than any fundamental change in the Guard’s makeup. As an artist as well as a soldier, Meissonier painted the horror that he witnessed first-hand. The Barricade, a quickly sketched watercolour, depicts the aftermath of civil unrest in a direct, unfiltered way. He would later write:

When the barricade in the rue de la Mortellerie was taken, I realized all the horror of such warfare. I saw the defenders shot down, hurled out of windows, the ground strewn with corpses, the earth red with the blood it had not yet drunk (T.J. Clark, The Absolute Bourgeois: Artists and Politics in France, 1848–1851, 27).

Meissonier would return to a similar composition years later with an oil on canvas rendition of The Barricade. Though tiny, this work depicts the horrific outcome of the insurrection in all its fullness. Painted in muted greys, blacks, and browns, the street scene is abandoned; the shutters of the buildings are closed, underscoring the silent finality of the battle’s aftermath. The foreground, in contrast, is animated by colour: the jewel-like paving stones, the smocks of red, blue, and white, and the stain of blood, these colours echoing those of the Republican flag. This disquieting pictorial strategy ensures that the viewer’s visual focus is drawn to the inanimate corpses strewn across the rubbled ground.

In Meissonier’s works, the depiction of dead revolutionaries is characterized by a sense of equality. Absent are any visual indicators of weaponry such as guns, pistols, or swords. The absence of a discernible leader, slogans on the walls, or placards contributes to a scene devoid of explicit revolutionary symbolism. The street itself lacks distinctive features, with no road signs or shop names.

However, Meissonier, drawing inspiration from the models he used for this purpose, ensures individualization among the deceased. Each figure is portrayed as distinct from the others, with unique facial features and a distinct physical presence. Despite this individuality, a sense of unity emerges through their shared brutal fate. The absence of overt political symbols allows for a more universal representation of the human cost of revolution, emphasizing the shared tragedy experienced by each individual depicted.

While Meissionier’s La Barricade is a passionate condemnation of the government’s brutal suppression of the 1848 riots, he is best known for his later depictions of Napoleon’s armies and military themes.

1.3

| Caricature and Social Critique

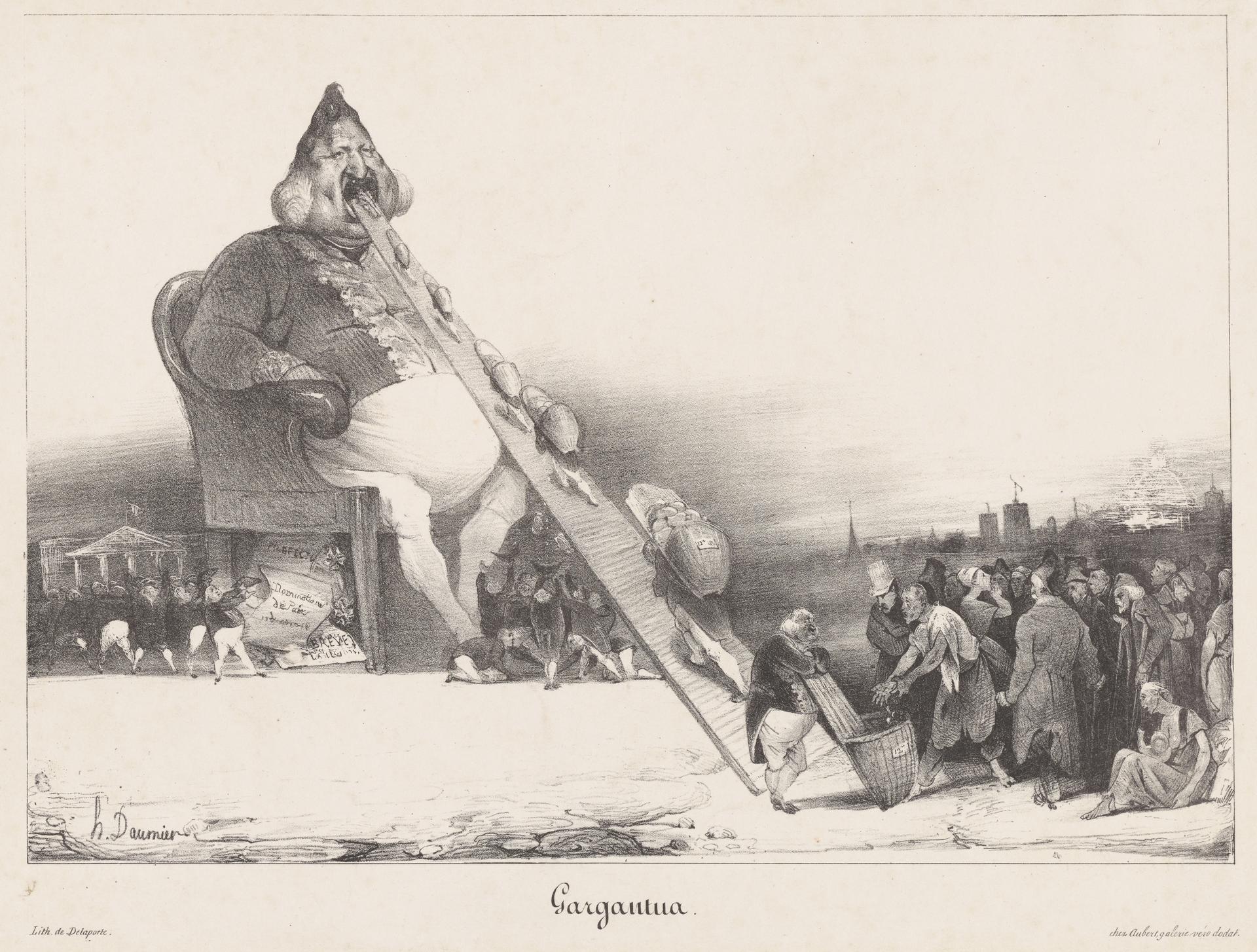

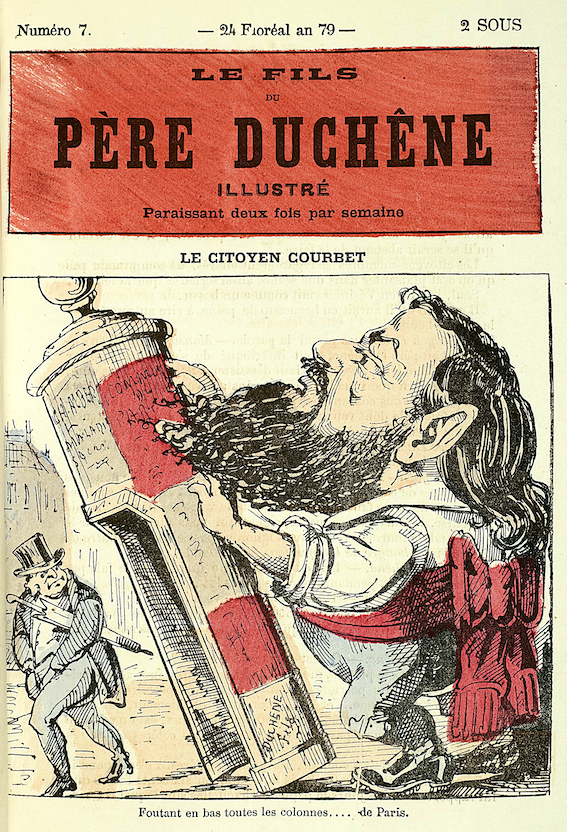

First published in the journal La Caricature, Daumier’s unflattering depiction of Louis-Philippe as a giant “Gargantua” devouring the resources of France’s beleaguered lower classes earned him a six-month prison sentence for insulting the king. When political satires became illegal in 1835, he turned his attention to images of French society.

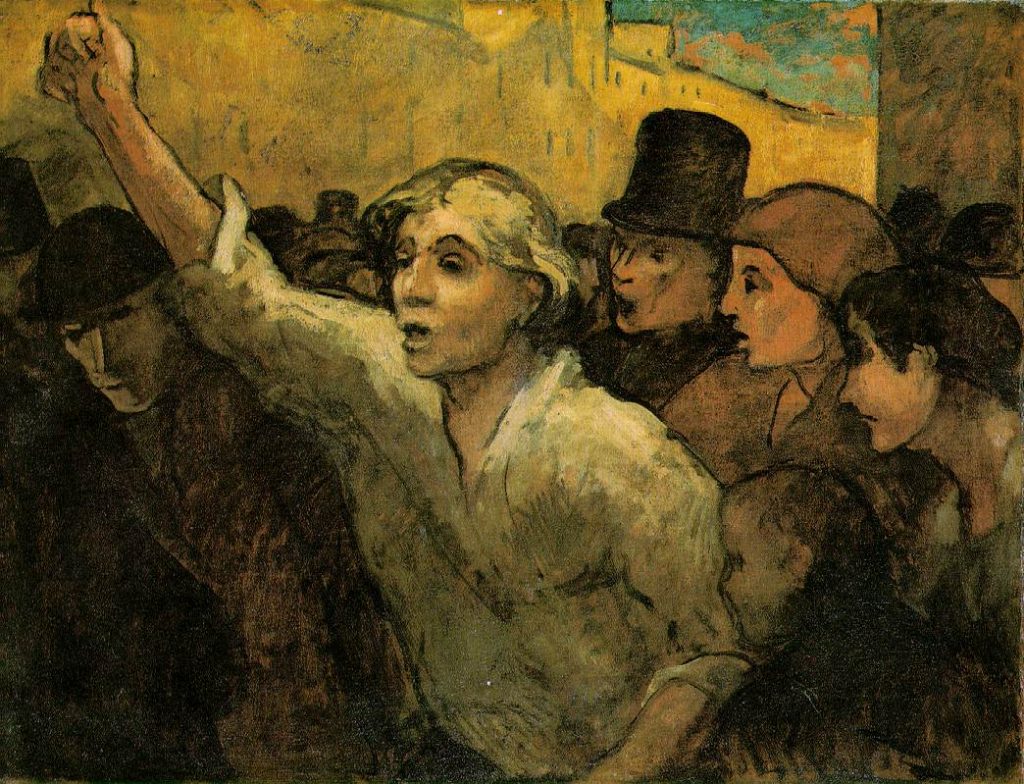

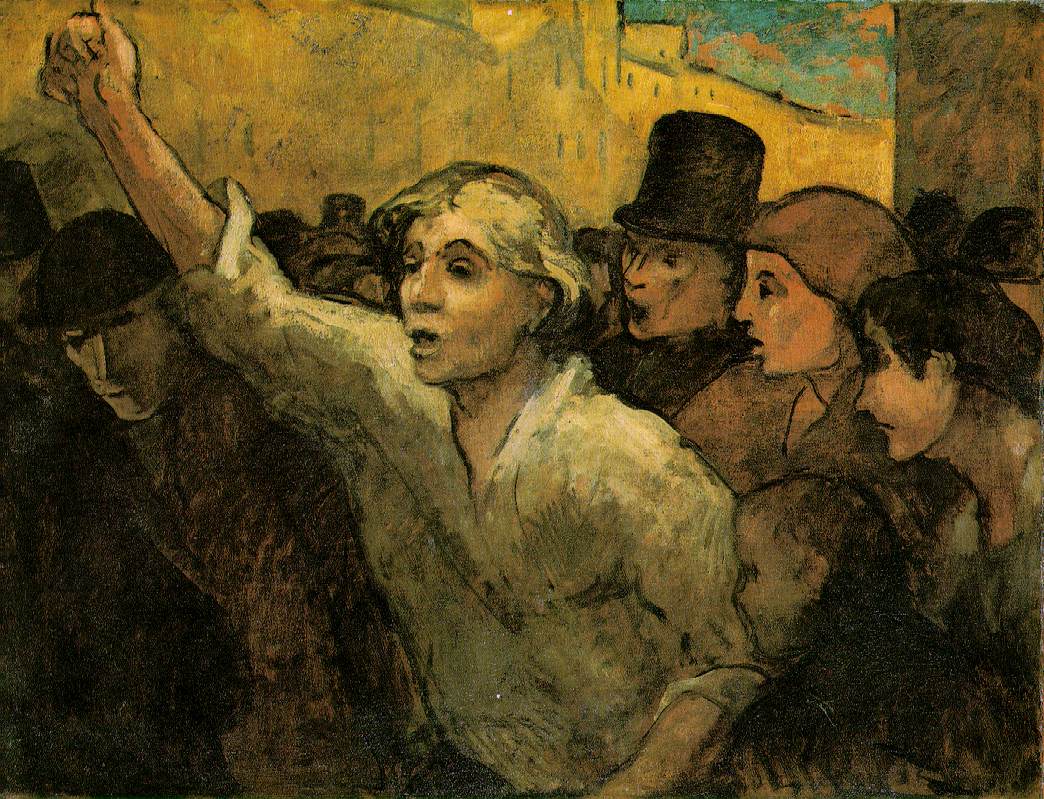

Unlike his mocking representations of officials and the bourgeoisie, Daumier’s paintings of the working class are sober works, sympathetically rendered. In Uprising, the artist depicts the protest from the perspective of the men and women involved, not from a distance, but as a direct experience. In this painting, a white-smocked worker leads an insurgent crowd, his arm raised in defiance, his mouth frozen in a battle cry. Marching beside him on the left is another worker in a chapeau melon(bowler hat), his features cast in shadow. The silhouette of a bourgeois in the front line is barely discernible save for the distinctive shape of his top hat. Another in similar dress rises above the multitude from behind the central figure. This second man’s deportment appears to align with the crowd’s leader, though indicated only by the tilt of his head and the few black smudges that mark out his visage. Together these men press forward in unison, with women and children visible among their ranks. Violent references (blood, weapons, the smoke of gunfire, the barricades) are deliberately left out. These workers are on the move, their actions spontaneous; they do not carry guns. Instead, the rebellion is described through the crowd’s unity of purpose. This solidarity is the subject of the work.

1.4

| Realism and the Democratization of Art

During the period when French society was advocating for democratic reform, avant-garde artists aimed to democratize art by turning their attention to “the everyman.” Before the mid-nineteenth century, the gritty and challenging life of the working classes was seldom a subject of artistic representation. When it was depicted, bourgeois painters often approached the subject with sentimentality and distant compassion, lacking a genuine engagement with the realities faced by the working class. The avant-garde, in its pursuit of democratizing art, sought to bridge this gap and bring attention to the everyday struggles and experiences of the common people in a more authentic and relatable manner.

While it’s important to acknowledge the diverse and, at times, contradictory approaches within the avant-garde Realist painters, the movement collectively rejected the “escapist” narratives associated with Classical Idealism. This rejection extended to the emphasis on Graeco-Roman standards of form, composition, theme, and subject, as epitomized in François Gérard’s portrait of Juliette Récamier. In contrast, Realists infused their work with allusions to the modern age, reflecting the profound disruption of historical continuity experienced by the entire population of Europe.

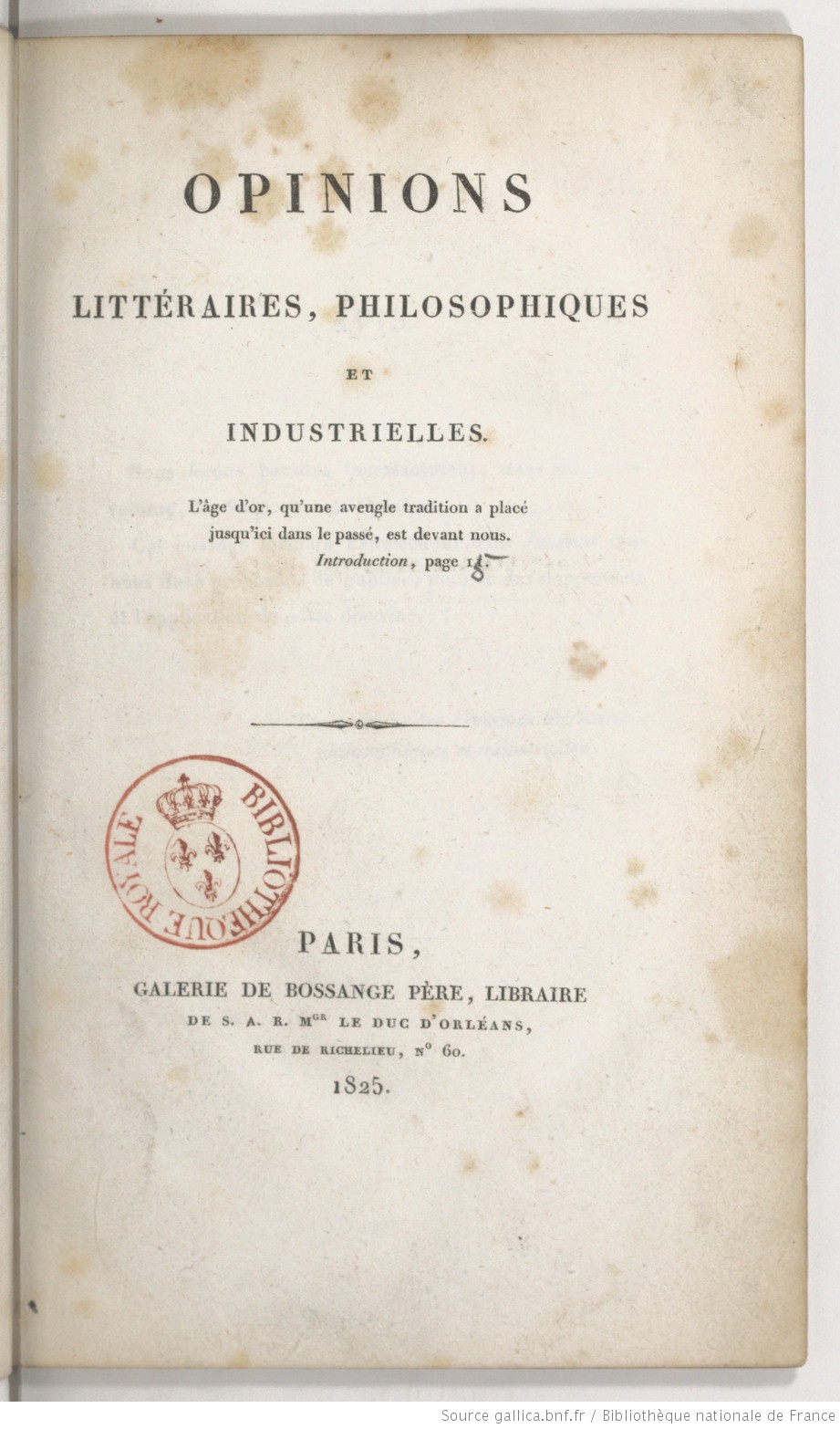

The term “avant-garde” first emerged within the context of art and culture at the beginning of the nineteenth century. The influential French thinker Henri de Saint-Simon, one of the forerunners of socialism, believed that artists, alongside scientists and industrialists, held social power and responsibility. In his 1825 book Opinions littéraires, philosophiques et industrielles (Literary, Philosophical, and Industrial Opinions), Saint-Simon wrote:

It is we artists who will serve you as avant-garde … the power of the artists is in fact most immediate and most rapid: when we wish to spread ideas among men, we inscribe them on marble or on canvas … What a magnificent destiny for the arts is that of exercising a positive power over society, a true priestly function, and of marching forcefully in the van[guard] of all the intellectual faculties. (Quoted by Donald Egbert, “The Idea of the Avant Garde in Art and Politics,” American Historical Review 73 (December 1967): 343)

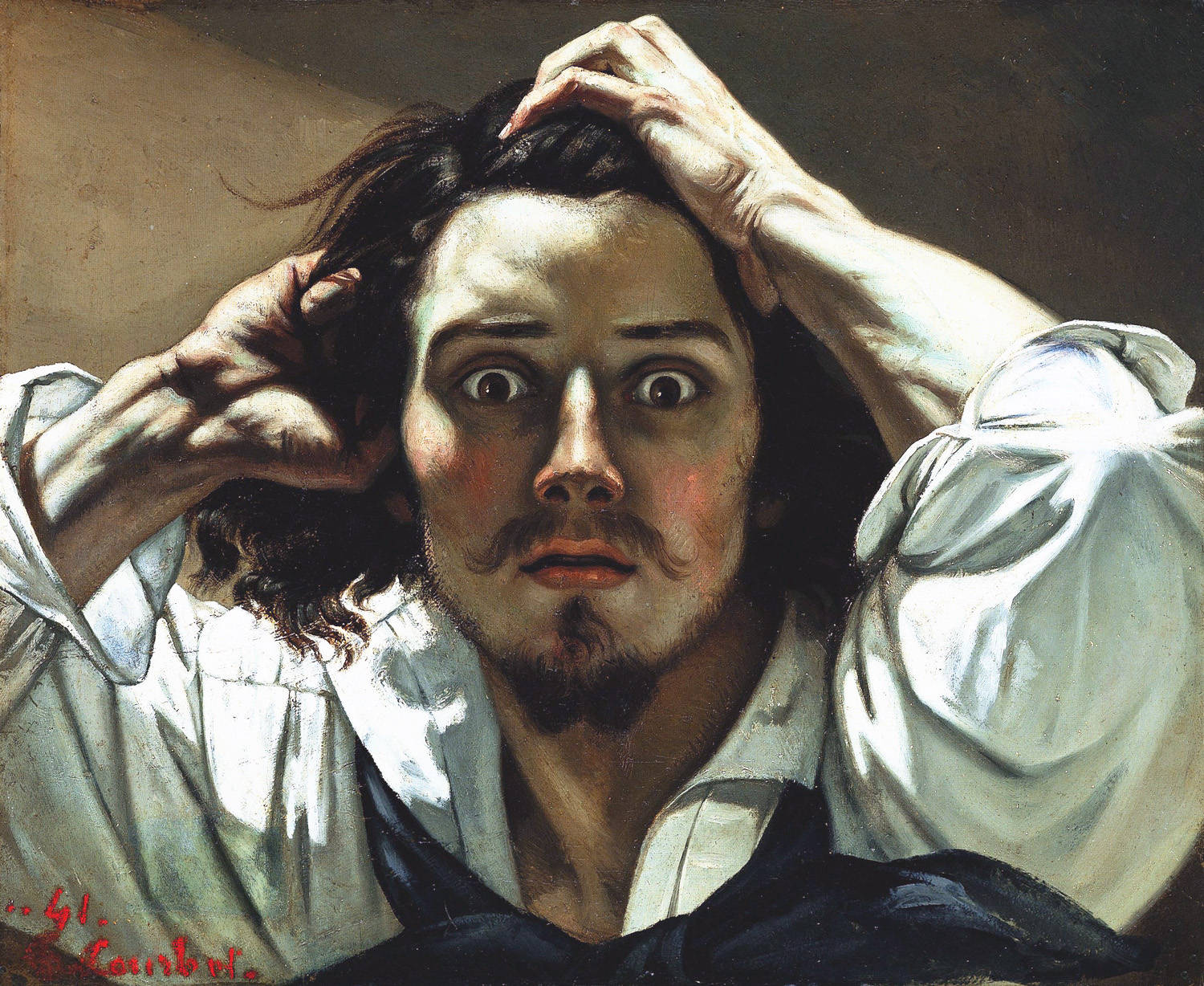

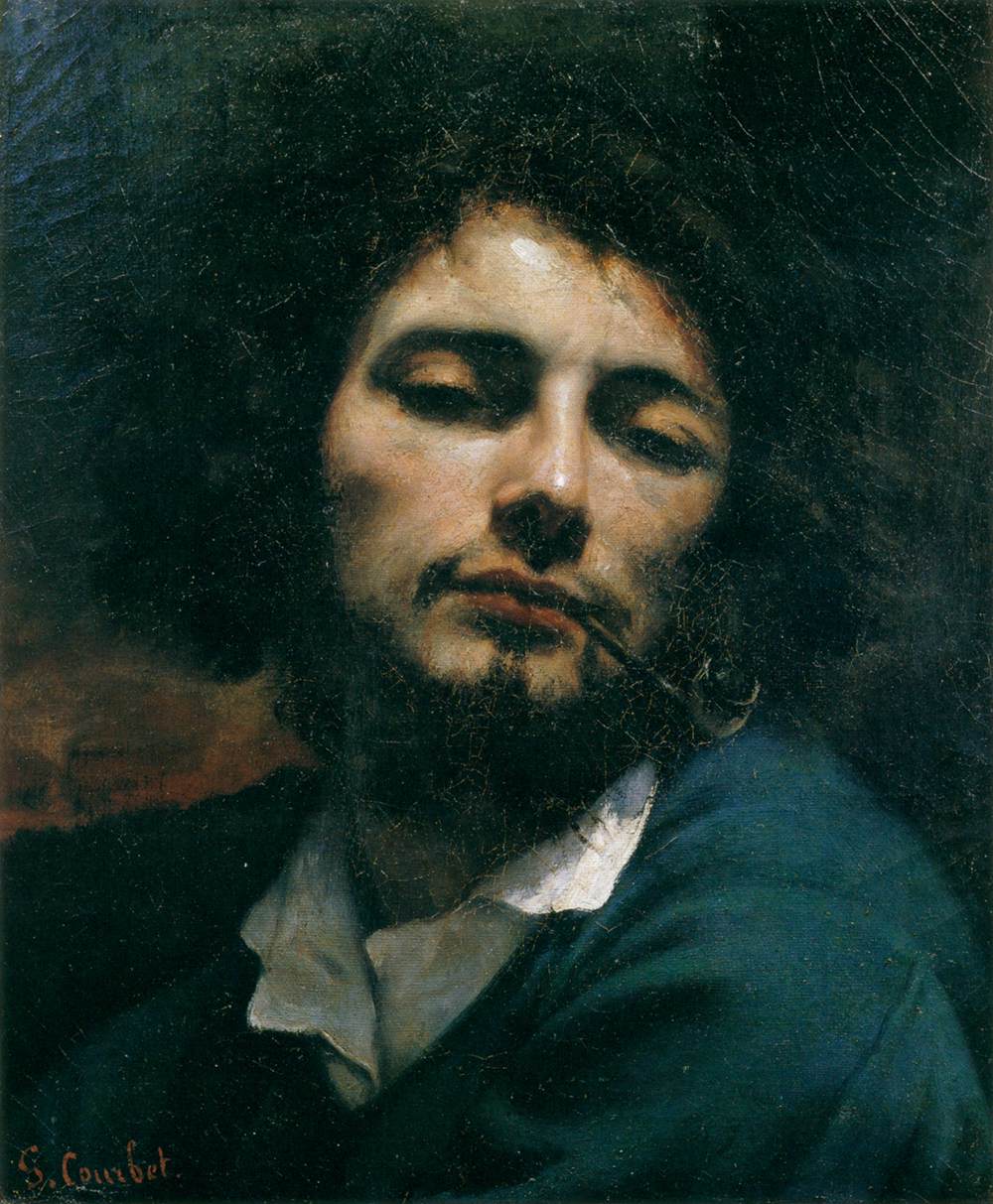

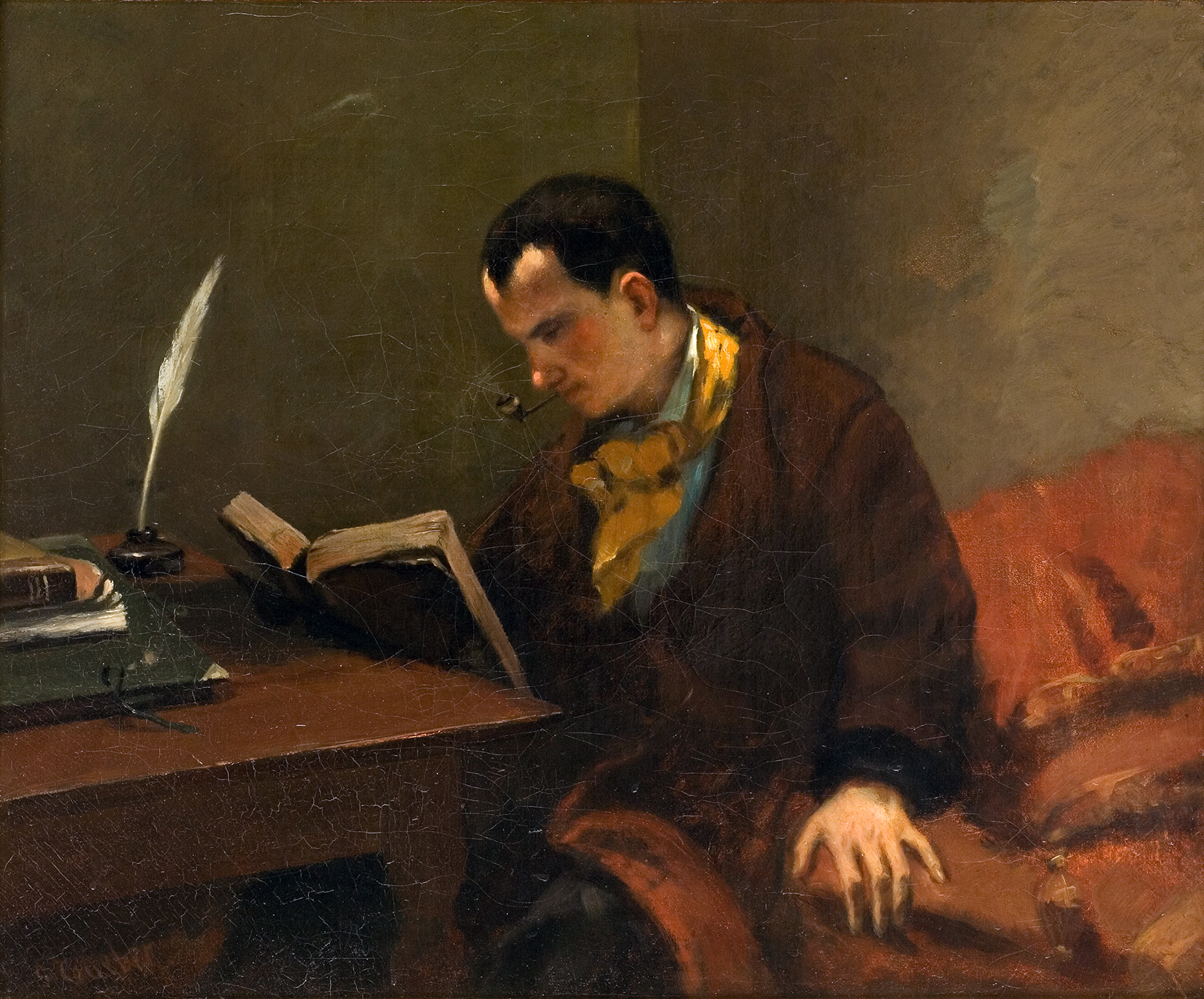

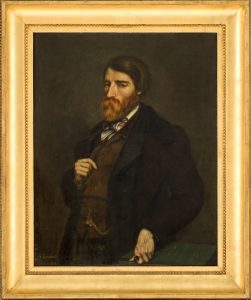

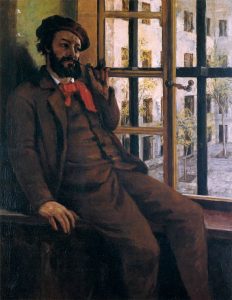

Self-Portrait with Pipe was bought from the artist in 1854, by his patron Alfred Bruyas. In a letter to Bruyas that same year Courbet described the painting as “the portrait of a fanatic, an ascetic … of a man disillusioned with the stupidities that have served as his education, and who seeks to establish himself in his principles.”

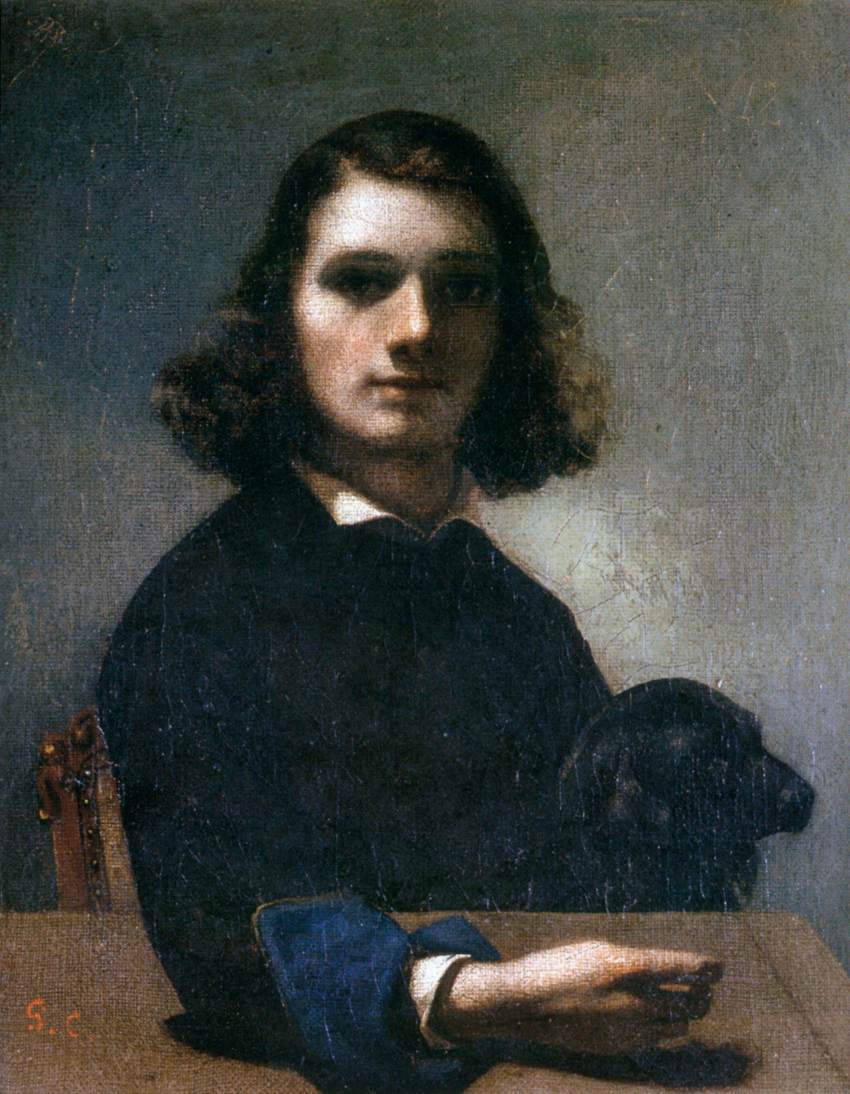

Courbet’s self-portraits from the 1840s, characterized by their honesty and directness, reveal his self-exploration as a budding artist without resorting to sentiment or allegory. In SELF-PORTRAIT WITH BLACK DOG, the artist’s introspective character is evident, especially in the gentleness with which he holds his dog, conveying a sensitive nature that elicits a sympathetic response from the viewer. The composition of the image bears a resemblance to Parmigianino’s 1523 self-portrait, where the hand is distorted due to the use of a convex mirror. This positioning of the right hand in Courbet’s self-portrait may allude to the manual dexterity of the painter, offering a glimpse into the artist’s skills and temperament.

Courbet painted a second Self-Portrait with Black Dog in 1842, which he reworked in 1844 and exhibited at the Paris Salon that year. His self-image captures his transformation from a provincial youth to an urbane artist. Courbet intended to study law when he arrived in Paris in 1839 but soon abandoned his courses to pursue a painting career. He portrays himself here as a debonaire young man, stylishly dressed in a frock coat and fancy patterned trousers, his hair long and curly beneath a floppy hat, holding a pipe in his hand. His black spaniel sits on one side while a sketchbook rests beside him. The lofty tilt of his head signals his rebellious bohemian attitude, while the country setting within which he is pictured speaks to his bourgeois roots in his native Ornans. By setting up a series of contradictions – landscape or self-portrait? Bohemian or dandy? – Courbet introduces the ambiguous character of his later work.

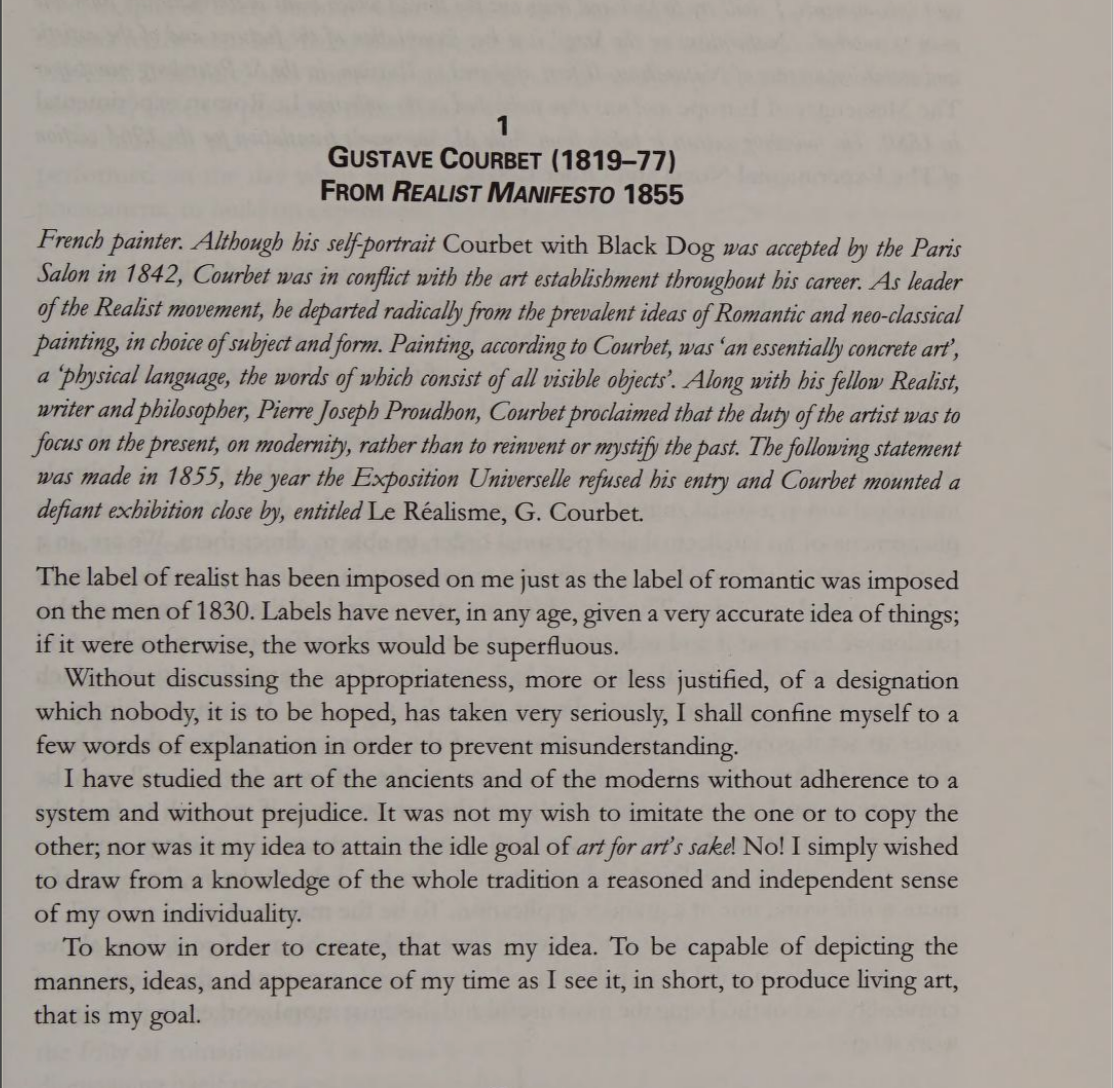

Courbet was essentially self-taught, rejecting the École des Beaux-Arts for private academies such as the Académie Suisse and Lapin and for independent study at the Louvre, where he went to copy masterworks by Spanish, Venetian, and Dutch artists. Courbet insisted that art could not be taught. His copying of old paintings was a starting point which did not end in emulation. As he stated in his Realist Manifesto in 1855: “The real artists are those who pick up their age exactly at the point to which it has been carried by preceding times. To go backward is to do nothing; it is pure loss; it means that one has neither understood nor profited by the lessons of the past.”

The American artist Samuel Morse captured the entrenched practice of copying the Old Masters in his enormous painting Gallery of the Louvre. The setting is the Salon Carré, where students were taught to sketch sixteenth-and seventeenth-century masterpieces by artists from Italy, France, Flanders, and Spain. The expanse of the Louvre is visible from the doorway at the back of the room. In the Salon Carré, paintings adorn the sequoia-colored walls in tightly arranged fashion, with classical sculptures occupying each corner of the room. A seated woman in the foreground pauses from her drawing as she listens to the comments of a man leaning over her shoulder. Beyond them, another lady sits in front of an easel while her companions discuss the artwork. A woman at a high table to the right works quietly at a book-sized easel, engaged in solo work. On the left, a man is depicted creating an original composition rather than copying the art on display. Morse’s painting provides a snapshot of the era’s art teaching methods and ideology, showcasing his adherence to academic art principles.

1.5

| Radical Realists: The Advent of the Avant-Garde

Gustave Courbet’s first atelier was situated at 28 rue Hautefeuille on the Left Bank, just a short distance from the Brasserie Andler. This bohemian establishment served as a gathering place for Courbet and a variety of progressive and unconventional figures of the era. Among these notable individuals were Charles Baudelaire, a poet and art critic, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, a socialist philosopher and anarchist, and Jules François Felix Fleury-Husson, an art critic and novelist who wrote under the pseudonym Champfleury. Courbet would paint portraits of these men as tokens of friendship and respect.

A prominent supporter of the Realist movement in painting and fiction, Champfleury was among the first to promote Courbet’s work. His short treatise Le Réalisme (1857) was, at the time, one of the only texts written about this stylistic movement. The affiliation between Champfleury and Courbet was so strong that Alfred Delvau, a French journalist, collegially parodied it in his Histoire anecdotique des cafés et cabarets de Paris (1862). This was a book of anecdotes illustrated with etchings by a handful of artists, including Courbet. In a chapter headed by Courbet’s depiction of the Brasserie Andler’s moody, gas-lit interior, Delvau describes the gaggle of admirers that gathered around the two Realist figureheads, saying: “And in this temple of Realism, where M. Courbet was the sovereign pontiff and M. Champfleury the cardinal officiating, the audience of drinkers—students, and wood engravers included—consisted only of realists and non-realists.” (translation of Alfred Delvau, Histoire anecdotique des cafés et cabarets de Paris (Paris: E. Dentu, 1862), 4).

The young and ambitious Courbet was well-surrounded in this tightly-knit circle. In 1848, he wrote an exuberant letter to his father, Regis, telling him: “I am about to make it any time now for I am surrounded by people who are very influential in the newspapers and the arts and who are very excited about my painting. Indeed, we are about to form a new school, of which I will be the representative in the field of painting.” (Quoted by Albert Boime, Art in an Age of Civil Struggle, 1848-1871 (University of Chicago Press, 2008), 144).

1.6

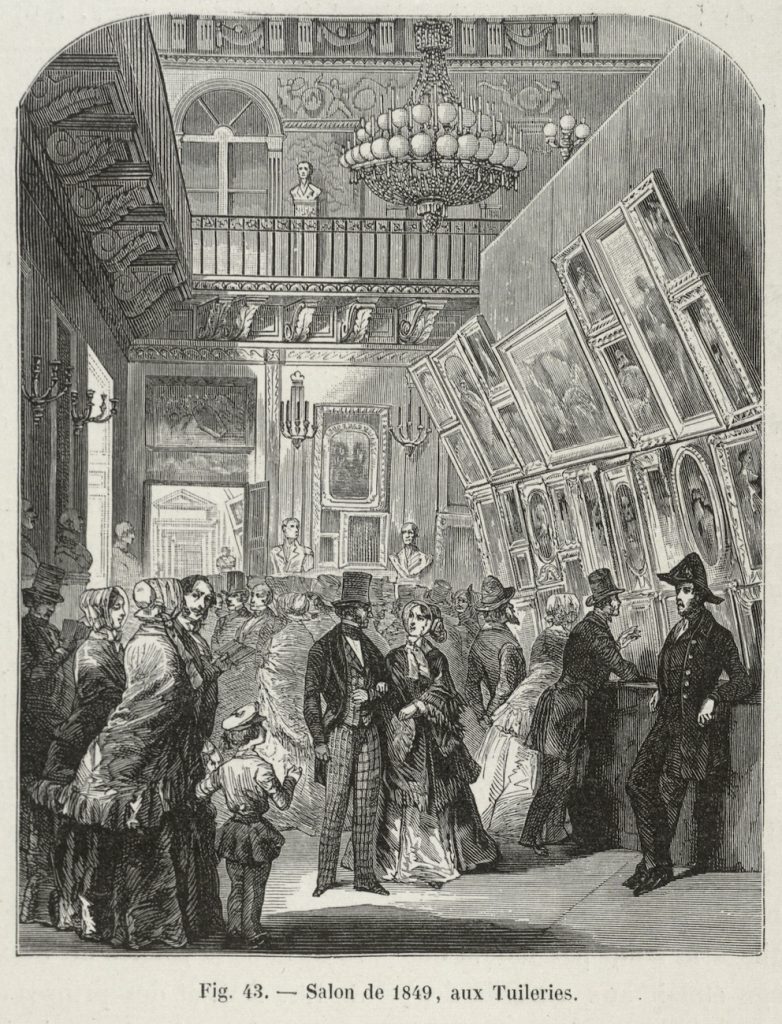

| Gustave Courbet and The Paris Salon

The following year, After-Dinner at Ornans (1849) was one of the eleven works Courbet exhibited in what was considered the first Salon of the Second Republic.

After Dinner is a commonplace scene of an interior gathering in Ornans; several friends, including Courbet’s father, sit around a country table as one plays the violin. The intimate provincial scene would typically have been rendered on a small scale. Yet Courbet has chosen to paint it in the grandiose dimensions traditionally reserved for historical works. His elevation of “the everyman” to heroic proportions marked Courbet as an audacious radical and implicated him in the era’s social politics.

In its simplicity and sober qualities, After-Dinner at Ornans presented a stark contrast to seventeenth-century Dutch School genre scene paintings that Courbet would have been familiar with. For one, Dirck Hals’ Merry Company at Table exhibits the sentimental triviality with which artists were taught to depict ordinary folk well into the nineteenth century. Courbet’s rendering was so strikingly original that it impressed his early supporters, including Francis Wey, a fellow Franche-Comtois and man of letters who later became Courbet’s friend. In his memoir, Wey recalled being astonished at the freshness and accomplishment of this work by a then-unknown artist.

1.7

| Painting Ordinary People: Elevating the Humble Hero

After exhibiting After Dinner at Ornans, Courbet retreated to Ornans to reflect upon his future. In a letter to friends, he wrote: “I am a little like a snake … in a state of torpor. In that sort of beatitude, one thinks so well! …Yet I will come out of it” (quoted by Stephen Eisenman, “The Rhetoric of Realism: Courbet and the Origins of the Avant-Garde” in Stephen F. Eisenman et al., Nineteenth Century Art A Critical History (London: Thames and Hudson, 2002), 212).

During his time away from Paris, Courbet painted three colossal pictures now considered to be among his defining works: The Stone Breakers (1849), A Burial at Ornans (1849), and The Peasants of Flagey Returning from the Fair (1850–51).

The Stone Breakers encapsulates Courbet’s interest in depicting humble subjects. It shows two men at work breaking stones to surface a road. The labourers are almost life-sized; they dominate the canvas. The young man at the left, a novice, appears to struggle beneath the weight of the heavy stone; beside him, the old labourer is rigid and deliberate in his actions. The difference in their ages may have been intended as a commentary on the cycle of poverty in a labourer’s life, from childhood to old age.

Courbet’s canvas is imbued with signs of hardship and deprivation. The figures depicted wear tattered clothing, and the meager meal situated to the right of the painting offers neither adequate nourishment nor respite from work. The limited palette, featuring greys, bleached blues, earthy whites, and browns, contributes to a somber mood. The figures seamlessly blend into their surroundings, emphasizing their inherent connection to the land and labour. Notably, Courbet deliberately obscures the faces of the men, rendering them anonymous. This choice serves as a pointed commentary on their inferior social status and societal invisibility.

Courbet’s rough brushwork represents a deliberate rejection of the Neoclassical finish that had previously dominated French art. In this painting, the perfection of line and form takes a backseat to the spontaneous application of paint, reflecting an immediacy of execution that aligns with the artist’s direct observations and contributes to the authenticity of the scene.

I stopped to contemplate two men who were breaking stones on the road. It is not often that one encounters the most complete image of poverty, and so, right then and there, I got the idea for a painting

Soon after completing The Stonebreakers, Courbet wrote to his friend Francis Wey, a French writer, art and pioneering photography critic (Courbet, Letter to Wey, December 12, 1849, trans. in Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, ed. Letters of Gustave Courbet (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 89-90):

One side is an old man of seventy, bent over his work, his sledgehammer raised, his skin is burned by the sun, his face is shaded by a straw hat. His pants, of a coarse material are patched everywhere, and inside his patched clogs his heels show through socks that were once blue. On the other side a young man with dusty hair and a swarthy complexion. His filthy and tattered shirt reveals his sides and arms. A leather suspender holds up what is left of his trousers, and his muddy leather shoes show gaping holes on every side. The old man is kneeling, the young man is standing behind him energetically carrying a basket of broken stones. Alas, in that class that is how one begins and that is how one ends up. Scattered here and there is their gear, a hod, a hand barrow, a hoe, a farmer’s cooking pot, etc. All of this takes place in bright sunshine, in the middle of the countryside beside a ditch next to the road. The landscape fills the canvas.

When The Stone Breakers was first exhibited, it drew both attention and condemnation. Critics accused Gustave Courbet of engaging in socialist propaganda, an accusation that he likely embraced and defended. Courbet expressed his views on Realism and its democratic nature, stating, “Realism is essentially democratic art.” This assertion was made during a conference of artists in Antwerp in 1861, showcasing Courbet’s commitment to the democratic ideals inherent in his approach to art. The quote is sourced from K. Herding’s work, “Courbet (Jean-Désiré) Gustave,” published in Grove Art Online, with a translation of G. Riat’s “Gustave Courbet: Peintre” (Paris, 1906), pages 191-192. This is what he said in Antwerp in 1861 when he participated in a conference of artists. (Quoted by K. Herding, “Courbet (Jean-Désiré) Gustave,” Grove Art Online, translation of G. Riat, Gustave Courbet: Peintre (Paris, 1906), 191-92):

The basis of realism is the denial of the ideal … We must be rational, even in art, and never allow logic to be overcome by feeling … By reaching the conclusion that the ideal and all that it entails should be denied, I can completely bring about the emancipation of the individual, and finally achieve democracy. Realism is essentially democratic art. reaching the conclusion that the ideal and all that it entails should be denied, I can completely bring about the emancipation of the individual, and finally achieve democracy.

Some viewers were struck by the social commentary embedded in the painting. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who considered labour as a form of property rightfully belonging to the proletariat, notably characterized Courbet’s “The Stone Breakers” as an ironic commentary on industrialized society. In a description from 1865, Proudhon described the movement of the older man in the painting: “His rigidified arms rise and fall with the regularity of a lever. There certainly is the mechanical or mechanized man, in the desolation made for him by our splendid civilization.” This quote is sourced from “Realist Impulse in Nineteenth-Century Art,” Nonsite no. 27 (February 11, 2019), with a translation of Proudhon’s work “Du Principe de l’art et de sa destination sociale, 1865” (Paris: A. Lacroix) 1875.

A Burial at Ornans was started soon after The Stone Breakers, the artist referring to it as a tableau historique [history painting]. Its original title was Tableau de figures humaines, historique d’un enterrement à Ornans.

A Burial at Ornans captures the gathering of villagers from Ornans at the graveside, portraying various groups and individuals with distinct roles and relationships. The elders, including Courbet’s great-uncle and individuals who experienced the French Revolution of 1789, are depicted closest to the grave. Courbet’s parents and friends, with his father wearing a top hat at the center, are present, and his mother is shown offering comfort to Teste’s daughter on the far right. The stout, bearded mayor is prominent in the foreground near the grave. The younger generation is represented on the right, featuring Courbet’s three sisters, who are shown holding handkerchiefs to teary faces. Notably, Courbet includes his deceased grandfather Oudot, whom he held in deep affection.

Black forms the basis of A Burial at Ornans, with various colours playing against it: the flesh colour tones of the hands and faces; the stark white of handkerchiefs and collars, lace caps, spats, the priest’s trimmings, the gravedigger’s sleeves, and the glossy fur of the dog.

At the left, where officials are carrying out the requirements of Christian burial, Courbet has intensified his palette with notes of strong colour, in the beadles’ costumes, for example.

In the centre foreground are the edges of the burial pit, flanked by a skull, and the gravedigger Antoine Joseph Cassard, the son of a local shoemaker. The man’s jacket and woollen hat on the ground are set against the brownish tones of the soil. An aide carries the cross, and behind him is the sacristan.

The prominent crucifix in A Burial at Ornans is set against a vast skyline and centred among the craggy hills of Roche du Mont and Roche du Chateau. The hills define the landscape of Ornans and are given equal pictorial weight. In this sense, the very landscape of Ornans is raised to the level of a holy symbol. A sombre mood permeates the painting, matching the dour faces peering into the open grave at the bottom of the image. Everyone seems to reflect on the very real knowledge that this scene will be replayed again and again for each of them. Painted on a scale meant for historical figures, the ordinary people pictured and the landscape Courbet revered are elevated to the status of classical subjects. Yet Courbet accomplishes this without succumbing to idealization or sentimentality.

Traditionally, artists sought to infuse representations of death with a spiritual dimension, but Courbet has not done so here. Instead, the sensations attached to the here and now permeate the work.

The depiction of Courbet’s figures in A Burial at Ornans may be compared to The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, by the Spanish Renaissance painter El Greco, particularly in how the officials and individuals are laterally represented in the foreground. But significant differences are evident when viewing the upper plane, where El Greco’s painting is laden with religious symbology. Unlike the works of the Spanish artist and others, Courbet had no spiritual message to impart.

Courbet’s A Burial at Ornans departs from traditional conventions in other ways, in its massive dimensions, for example, a scale previously reserved for historical and religious subjects. Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii, painted in 1786, provides a typical example of the monumental history genre favoured by the French Academy.

Courbet’s choice of subject was a deliberate act of rebellion against the prevailing norms of academic art. The painting represented a clear rejection of the grandiose themes and glorious events often depicted in academic works. Instead, Courbet opted to focus on the commonplace and the everyday life of his community. His work was regarded as an affront to conventional art and severely denounced.

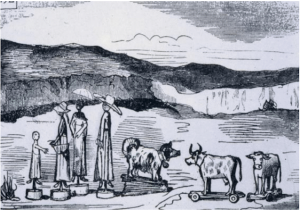

The Peasants of Flagey was the third in Courbet’s trilogy of monumental depictions of rural life.It provoked controversy due to its realistic portrayal and unconventional stylistic choices. Courbet’s use of awkward composition, coarse technique, and the unconventional representation of people and animals challenged the established norms of academic art. The figures in the painting represent landowner farmers from the Doubs region, who engaged in the buying and selling of livestock at the fair while living in close proximity to the animals. The direct and unidealized depiction of the farmers and their entourage conveyed the actual conditions of rural life, including the integral presence of farm animals.

Courbet addressed the subject of female labour in The Wheat Sifters, painted several years later. In it, two women prepare harvested wheat to be ground into flour. One of them, seated at the left, idly picks through a tray, while her companion in a red dress has taken up the more strenuous task of shaking a large sieve to separate the grain from the stalk. The models are likely Courbet’s sisters, Zoé and Juliette, and the young boy playing in the foreground might be Désiré Binet, the artist’s illegitimate son.

Courbet articulates the central figure in monumental terms, underscoring the strength required for the chore by exaggerating her strong arms, outstretched to sift the grain. Her body is anchored against the movement by her knees pressed to the ground. Her figure is remarkably forceful. She has turned her back on the viewer, drawing attention to the physical act of labour.

Jean-François Millet, a Courbet contemporary, also highlighted the work of rural female labour, gaining recognition for The Gleaners of 1857. Although they were both realist painters and shared an interest in similar subjects, Millet’s work was more widely accepted than Courbet’s, perhaps due to its suggestion of a spiritual dimension. The Gleaners seems to echo the biblical story of Ruth, in which a young widow provides for her destitute mother-in-law, Naomi, by gleaning a wealthy landowner’s field. The landowner, touched by her act of kindness, offers marriage and security.

This narrative of self-sacrifice and just reward underlies the subject of a trio of women picking up the scraps left behind by the harvesters. The empty field contrasts with the landlord’s abundant haystacks and sheaves of wheat in the distance. A man on horseback at the far right, probably an estate steward, supervises the work underway. The gleaners are visually and aesthetically distanced from the background activity by a stark shift in scale and luminosity, appearing large and weighted in the foreground. Their bent postures and Millet’s heavy application of paint emphasize the physical hardship of their task. Due to its religious overtones, The Gleaners implies something beyond the fact of peasants performing a routine task. It conveys the comforting suggestion of a moral recompense for hard work.

Like Courbet, Millet came from a rural background, although his experience included hands-on farm work from a young age. His interest in peasant imagery was, therefore, profoundly personal. Millet’s affinity with his subject matter would sometimes get him into trouble. At the Salon of 1863, Millet presented a canvas titled Man with a Hoe that caused a storm of controversy. Not only was the central figure of the painting seen as brutish and disturbing, but the Parisian bourgeoisie interpreted the work as a blatant socialist critique.

Millet, resisting the attempts to be classified as an agitator, said:

The gossip about my Man with a Hoe seems to me all very strange, and I am obliged to you for letting me know it, as it furnishes me with another opportunity to wonder at the ideas people attribute to me… My critics are men of taste and education, but I cannot put myself in their shoes, and as I have never seen anything but fields since I was born, I try to say as best I can what I saw and felt when I was at work. (Quoted in Robert Goldwater and Marco Treves, Artists on Art (New York, 1945), 292-3)

Tensions were mounting between the cosmopolitan industrial elite and the rural labourers threatened by the gradual mechanization of agriculture and the collapse of grain prices. In this context, Millet’s Man with a Hoe was seen as provocative by conservatives who recalled the recent peasant uprisings. Though his paintings were always judged in political terms, Millet insisted that he was neither a socialist nor an agitator. Instead, as a religious fatalist, Millet believed everyone was burdened by their destiny. To him, this farmer was ‘everyman,’ and this painting was a tribute to the dignity and courage of the peasant. However, despite this political disavowal, Man with a Hoe was long considered a symbol of the labouring class.

Courbet may have found historical affinities in the oeuvre of the 17th-century Le Nain brothers, Antoine, Louis and Mathieu, and their small-scale works of French peasant life. He would have had access to these works when the Louvre Museum, housed within the Louvre Palace, was being reconfigured to exhibit paintings, industry products, and house a national library.

After the February Revolution of 1848, Philippe-Auguste Jeanron, painter of scenes from proletarian life, was appointed Head of National Museums and Director of the Louvre. Favouring painters of the people, Jeanron gave greater attention to hitherto neglected artists like the Le Nain brothers.

Champfleury, among others, praised the Le Nain brothers for their realistic depictions of humble life. He wrote about them in 1849, following his introduction to their work. Charles Blanc would echo his admiration in the fifth volume of his Histoire des peintres de toutes les écoles (The History of the Painters of all Nations), published in 1852: “This Le Nain (Louis or Matthieu) is a true French painter, a full-blooded Frenchman… No foreign element has intervened to temper his rough Gallic manner.” Champfleury, who cites this passage at the end of chapter 12 of his landmark monograph of 1862, Les peintres de la réalité sous Louis XIII: Les frères Le Nain (Painters of Realism under Louis XIII: The Brothers Le Nain), urges readers to “set aside Watteau, Boucher, Fragonard, and focus on a more glorious French school: the Clouets, the Poussins, the Champaignes, the Le Nains.” Champfleury noted that the aims and methods of the LeNain brothers could also be found in Courbet’s A Burial at Ornans.

But Courbet’s paintings were criticized by others for resembling the working method of daguerreotypists of the mid-nineteenth century. In 1878, French art historian and writer Paul Mantz commented that Courbet resembled the Le Nains, who posed models like a photographer, saying, “don’t move.” Courbet’s paintings were belittled by comparing them with the photographic image.

The art critic and novelist Champfleury refused to confine realism to a single concept. The only principle he recognized, he said, was sincerity in art. Champfleury insisted that realism could not be a mechanical process of simply imitating what one saw: “Man’s reproduction of nature will never become a reproduction or an imitation, but will always be an interpretation for no matter what man does to enslave himself to copying nature, he will always be caused by his particular temperament . . . to render nature according to the impression he receives.” (Champfleury, Le Réalisme (Paris: Hermann, 1973, 10, 92–3)

Champfleury’s turn toward more overly-realist realism occurred in the 1850s, especially with the publication in 1857 of Le Réalisme. The book was published as a collection of essays from newspapers and periodicals instead of a coherent treatise.

Champfleury, Le Réalisme (Paris: Michel Lévy Frères, Libraires – Éditeurs, 1857), 273, 274, 275

In a letter to George Sand, a French novelist and journalist, in July 1855 where he writes about Courbet and realism, Champfleury struggles to define the very term: “Je ne vous définirai pas, madame, le réalisme; je ne sais d’où il vient, où il va, ce qu’il est; Homère serait un réaliste, puisqu’il a observé et décrit avec exactitude les moeurs de son époque [I will not define realism to you, madam; I don’t know where it comes from, where it is going, what it is; Homer would be a realist, since he observed and accurately described the mores of his time]. In this instance, he extends the concept of realism to include the perception of a particular time and place, and associates realism with exactitude of observation and description, creating the possibility of absolute equivalence between writers and their subjects.

Jules-Antoine Castagnary, meanwhile, argued that: “Visual art can be neither a copy nor even a partial reproduction of nature, but rather an eminently subjective product . . . expressing a purely personal conception. . . Above all, art is an expression of the human self solicited by the external world . . . it is one of the highest acts of human consciousness.”

1.8

| A Class in Transition: Courbet’s Young Ladies

When Courbet’s Les Demoiselles de Village was exhibited in the Salon of 1852, it was seen as the quintessential representation of the vices of realism. Critics commented on its lowly details, ineptitude of composition, faulty rendering of perspective, the ugliness and awkwardness of the figures and the painting’s total disregard for the established canons of beauty and good taste.

Young Ladies of the Village depicts Courbet’s three sisters, Zoé, Juliette, and Zélie, the latter shown giving alms to a young cowherd.

Young Ladies of the Village was satirized in the Journal pour rire. Courbet’s sisters were shown as dummies on stands, while the cattle stood on wheels, and the dog looked like a toy. The caricature pointed to the lack of integration in Courbet’s painting. This may have been because Courbet was accustomed to painting landscape settings out-of-doors and figures in his studio.

The critic Anatole de La Forge, active in politics all his life, wrote a book on art entitled La peinture contemporaine en France (1856). In it, he clearly articulated many underlying attitudes to the work: “Once upon a time, there were girls in the villages and young ladies in the towns, and the world wasn’t the worse for that. Today vanity, this familiar demon, is encouraging country people to abandon their fine dress in order to decorate themselves out in our bizarre fashions. So attired, village girls are passing for young ladies.”

It was apparent to contemporaries that Courbet’s subjects were not “young ladies” but a lower class of females. For one thing, there was an enormous gap between the attire worn by Courbet’s women and what was fashionable at the time.

In Courbet’s painting, the dresses worn by the women are noticeably absent of crinolines so that the dresses fall limply from their waists.

This style had not been fashionable since the first decade of the century. Additionally, a real young lady would not go out without gloves; the mere sight of women’s hands would instantly convey to Parisians that these women were of a lower class. Using a straw basket as an accessory was another indicator of the women’s social status. Fashionable ladies carried parasols, fans, and embroidered handkerchiefs; only peasants carried straw baskets.

Critics also explained how social class could be revealed through body language. The awkward bearing of the sisters is emblematic of a class in transition, neither peasant nor lady. Courbet’s painting indicates the gap between their social aspirations and social reality. When read from left to right, the painting conveys the upward mobility that resulted in the transformation of peasant girls into young ladies.

In Young Ladies of the Village, Zélie, standing next to the young peasant girl, represents the next stage in transitioning from peasant to young lady. Zélie is part of the rural bourgeoisie but does not yet set herself apart from the peasantry.

Then, Juliette, the most ungraceful of figures, is attempting to be a real lady but failing miserably. Finally, Zoé, the most graceful, has transitioned to the urban bourgeoisie and is the farthest from a peasant girl.

The painting is at once autobiographical and historical, drawing on the history of the artist’s own family to illustrate broader socio-economic developments in nineteenth-century France. Courbet conveys the disappearing rigidity of the class structure out of which he, as a member of the rural bourgeoisie, arose. Paris in 1851 was sensitive to questions of rural society for straightforward political reasons. The city was a fragile, self-conscious illusion, a prey to the multitude of immigrants.

The French Rococo painter Jean-Antoine Watteau’s The Fortune Teller appears to have been utilized as a specific prototype. Not only are the positions, poses, and gestures in The Fortune Teller strikingly similar to those in Courbet’s painting, but Courbet must have been taken with Watteau’s spotted, bushy-tailed dog, as he copied it in his painting. Courbet chose to borrow directly from an image in which Watteau depicted two classes.

Courbet’s use of the word “demoiselles” here in 1851, appearing for the first time in his titles, may have intended as a specific historical reference to the class conflict between peasants and the bourgeois. “Demoiselles” was the word used to characterize a band of peasants who in 1829 disguised themselves in bonnets and long shirts and, armed with guns and axes, prowled the countryside at night attacking police, forest guards, and hated landowners. The “War of the Demoiselles,” as it had been called, reflected the early nineteenth-century peasant’s resentment and fear of bourgeois control. In keeping with his abhorrence of physical conflict, it is possible Courbet painted his own demoiselles as a pacifist response.

Courbet’s inspiration for such political moralizing probably had its source in several contemporary tracts. One in particular was the perfect reference for Courbet in 1851, Louis-Napoleon’s (1808–1873) book The Extinction of Pauperism. Written in exile and first published in 1844, it was hailed by the Left but ignored by its author after he became emperor in 1852. A study of poverty among the industrial working class, it called for a communal system of sharing that would see the recultivation of rural areas. His conclusion stated: “The working class has nothing, it is necessary to give them ownership. They have no other wealth than their own labor ….”

This Golden Age dream, which promised the elimination of poverty and unrest, was especially relevant in light of the real events of 1851, which included a coup d’état on December 1 and a peasant uprising on December 7. Publications were circulated to incite the peasant revolt; for example, the Almanach du village of that year stated: “Peasants you are the masters, the Kings of this country. It is up to you to change the face of France.”

Les Demoiselles du Village was Courbet’s response to the specific events of 1851 and to the larger ramifications of a bitter class struggle which affected mid-nineteenth-century French life.

Linda Nochlin succinctly captures the meaning of Les Demoiselles de Village in Misère: The Visual Representation of Misery in the 19th Century:

It represents Courbet’s three sisters—Zoé, Juliette, and Zélie—as well as the object of their benevolence, a ragged, barefooted little guardian of cattle, in a peaceful pasture at the foot of the Roche de dix heures near Ornans. Although Courbet, during this period immediately following Louis-Napoleon’s coup d’état, was doubtless deeply upset by the ruler’s perfidy and the persecution and subsequent exile of his old friend Max Buchon, his avowed intentions in Young Ladies of the Village were far from inflammatory. Nevertheless, the letter in which he describes the project to Champfleury has an undertone of sarcasm that belies his conciliatory phrases: “It is hard for me to tell you what I have done this year for the Exhibition. I am afraid of expressing myself badly. You will be a better judge than I when you see my painting. For one thing, I have misled my judges, I have put them on to new terrain: I have made something graceful [charming]. All they have been able to say until now will be useless.”

But is this really an image totally lacking in a political agenda, a harmless genre scene in a sunny landscape? Certainly, it was not received as “charming.” Could the theme of charity—detached from religion, attached, specifically, to Courbet’s sisters and his home territory—itself raise hackles, a specter of insubordination or even revolutionary socialism at this moment in French history? Diane Lesko, in her excellent article on the Young Ladies of the Village, points out that the painting may have been meant as a not-so-subtle reminder to Louis- Napoleon that he had once been the author of a radical text on the subject of abject poverty, The Extinction of Pauperism.

Although far from being a simple piece of political propaganda, the allegorical potential of the Young Ladies of the Village cannot be thrust aside as irrelevant to the painter’s intentions and achievement. In an angry letter to the editor of the Méssager de l’Assemblée of 1851, in which he mentions that he is working on the Young Ladies of the Village, Courbet declares his allegiance to the cause of social radicalism: “M. Garcin calls me ‘the socialist painter.’ I accept that title with pleasure. I am not only a socialist, but a democrat and a Republican as well—in a word, a partisan of all the revolution and above all a Realist. But this no longer concerns M. Garcin, as I wish to establish here, for ‘Realist’ means a sincere lover of the honest truth.” In emphasizing his “Realist” affiliation along with his political ones, Courbet is referring both to the style, in the broadest sense, as well as the subject of his work. The Young Ladies of the Village bodies forth poverty and charity—the giving of bread to the needy, without either pathos or picturesque trappings—as an unsentimental everyday affair, concretely and materially represented in a setting that is the artist’s own countryside, rough, rocky, unmanicured. It is a small-scale act of justice, a benevolent gesture bridging the chasm separating the comfortable from the needy, that has much larger implications.

Several years later, in his Young Ladies on the Banks of the Seine (Les Demoiselles des bords de la Seine), Courbet would once more use the term demoiselles in a title as a provocative foil for examining social class and character. Along with the pictorial sumptuousness of the work, the finely painted fabrics, the detailed textural passages, and the captivating tonal play, the title reinforces the surface innocence of the work, which was immediately accepted by the jury for the 1857 Paris Salon.

But the image goes much further than Courbet’s sisters out walking on a Sunday. While it was a similar assertion of working women as valid subjects for serious painting, here, it is the sexual innuendo represented in pointedly contemporary terms that created controversy. The two fashionable ladies languidly reclining by the Seine presented a sharp contrast to the polished nudity of idealized goddesses in idyllic landscapes that the Salon public was accustomed to

Not surprisingly the painting caused an outcry. The ladies were not the coarse streetwalkers of the Boulevard, but their suggested intent was no different. To a bourgeois audience accustomed to allegorically encoded sexuality, this contemporary narrative, despite the scarcity of bare flesh and Courbet’s nod to codes of feminine decorum, was more disturbing, a breach of propriety worsened by the intentional title of Demoiselles. The journalist Maxime Du Camp labelled them lorettes, a term for prostitutes and critics such as Champfleury were outraged and incensed for reasons that extended beyond the depiction of lorettes, as argued by Petra ten-Doesschate in The Most Arrogant Man in France. Gustave Courbet and the Nineteenth-Century Media Culture (Princeton-Oxford, UK: Princeton University Press, 2007), 122):

It is puzzling that none of the contemporary reviewers of the painting addressed the déshabillé of the dark-haired woman. Is it that male critics were so little attuned to the details of fashion that they confused underwear with the newly fashionable white dress of the mid-1850s? Or was there a conscious or unconscious hesitation to address a topic for which the means of a bi-gendered public discourse had not yet been created? For sure, underwear was commonly depicted and discussed in women’s magazines in all the technical jargon necessary to explain the details of its complex construction…But the meaning of these words must have been lost on most men, whose vocabulary for women’s underwear was more readily found in dictionaries of slang.

“Clearly, Courbet does not understand anything about women,” Champfleury wrote to Max Buchon with reference to The Young Ladies of the Seine. Was it because the critic was mystified by the déshabillé, which could be interpreted as a gesture of seduction as well as one of defiance (a feminist rebellion against the rule that forbade women to shed any part of their elaborate clothing, while it allowed men to take off their jackets and vests for greater comfort)? Or was he puzzled by the incongruity of these femmes galantes, urban types par excellence, with their bouquets of wildflowers, emblematic of artlessness and innocence?” Or, to suggest yet another possibility, did Champfleury feel, as [Pierre-Joseph] Prudhon did, that there was something unsettling about the ‘slightly masculine’ (légèrement virils) features of the brunette, whom Prudhon associated with Lélia, the creation as well as the alter ego of George Sand?

All these ambiguities of Courbet’s painting seem comparable to the attempts of contemporary writers to erase or, at least, confound the boundaries between masculinity and femininity.

The women’s attire and their visible undergarments, particularly the dark-haired woman’s white lingerie, accentuated the connotation of immoral behaviour. But the absence of male “suitors” suggests another reading, that the scene depicts a lesbian encounter. This theme reappears in varied guises in paintings by the artist where two females are shown together. As Maura Reilly has discussed in “Le Vice à la Mode: Gustave Courbet and the Vogue for Lesbianism in Second Empire France” (Ph.D. diss., New York University, 2000), “Courbet’s “lesbian” paintings are situated along a spectrum, or continuum, which ranges from the suggestive to the overtly erotic and explicitly sexual. For example, his Bathers is deemed his earliest and most subtle exploration into the theme of lesbian eroticism, followed by Les Demoiselles des bords de la Seine, 1857, which is reread as an image replete with pictorial signifiers then associated with visual and literary lesbianism.”

As a definition, the term “lesbian” had a much more extensive range of connotations during the nineteenth century. While some women would have been sexually involved in same-sex relationships, others who did not ascribe to traditional models of social conduct, Amazons, androgynous, whores and witches, were also labelled as lesbians.

1.9

| Art, Patronage and The Outsider Artist

The collector Alfred Bruyas thought of himself less as a consumer of art than a collaborator, believing that by sponsoring and acquiring the work of select living artists, he could free them from the career constraints of the Salon system. In the early days of their friendship, Bruyas and Courbet saw themselves as partners in a project designed to advance contemporary art’s social and moral mission.

The Meeting was possibly begun in Montpellier and finished in Ornans. Courbet was aware of Bruyas’s interest in befriending the artists whose works he collected. He knew that Bruyas wanted to commission a painting that would be emblematic of their new relationship. The subject itself is accurate but only partially faithful to the event. Courbet would have traveled not by coach but by the new railroad line; there would have been no occasion for him to be met in the open countryside.

The painting is a large double portrait that records the meeting of the two men from different social strata with different but interrelated societal roles. Bruyas as patron is dressed elegantly and accompanied by a manservant. Courbet, the artist, faces the two in shirtsleeves, apron, and trousers tucked into his spats and carries a folding easel on his back. The interaction betrays no sign of deference. Courbet portrays himself almost as a travelling apostle (of realism), confident and with a sense of high importance about his mission. He is the artist as an outsider and wanderer, recalling his youthful statement as he set out into the world “I am just setting out on the great, vagabond, independent life of a Bohemian.”

Courbet paints himself head held high, appearing much more important than his patron, a difference in scale unrelated to their relative placement in the picture. He conveys an ironic authority, and only he casts a shadow, a fact not lost on viewers or on Bruyas. One can see why the word vanity sprang to the lips of its first audience and the painting’s dubbing as “Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet!” but one can also see the narrowness of such a response. The artist tilts back his head to gaze thoughtfully at Bruyas, aware of the reciprocal nature of the relationship. He is not a creature of vanity but of pride.

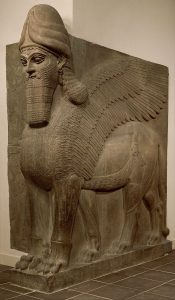

His profile pose, with a thick beard jutting directly downward from the chin, was a frequent motif in his paintings, notably in his 1855 Painter’s Studio, which he famously described as “myself painting showing the Assyrian profile of my head.”

Much Assyrian art consists of profile reliefs; protruding beards are a common characteristic. These contemporary allusions, however, did not attempt to emulate the specific knotting and shaping of Assyrian beards, and Courbet’s facial features are not directly comparable to the stylized Assyrian features. Courbet’s profile, that is, does not indicate a deep interest in Assyrian art. It would hardly be identifiable as Assyrian on its own. Instead, Assyria offers an occasion for the artist’s self-assertion. Courbet almost flaunts his lack of concern with the specifics of ancient art in a manner consistent with his subsumption of all past art to his contemporary concerns.

1.10

| Inside The Artist’s Studio

It is society at its top, bottom, and middle. In a word, it is my way of seeing society in its interests and its passions. It is the world come to be painted at my place …

Courbet wrote to Champfleury describing The Artist’s Studio in December 1854, as quoted from Correspondance de Courbet, ed. Petra ten-Doesschate Chu (Paris: Flammarion,1996), 121-22):

The Artist’s Studio is perhaps even larger than The Burial which will show that I am not dead yet, and nor is realism, since realism is a fact of life. It is the moral and physical history of my workshop.

It is society at its top, bottom, and middle. In a word, it is my way of seeing society in its interests and its passions. It is the world come to be painted at my place.

The scene takes place in my atelier in Paris. The painting is divided into two parts. I am in the middle, painting. To the right are all the shareholders, that is to say, my friends, my fellow workers, and amateurs from the art world.

To the left is the other world of … the exploited, the exploiters, people who live on death.

Beginning at the extreme left … at the edge is a Jew I saw in England making his way through the febrile activity of the London streets; religiously carrying a money-box on his right arm; while covering it with his left hand he seemed to be saying, “It is I who am on the right track.”

Behind him is a priest with a triumphant look and a bloated red face.

In front of them is a poor withered old man, a republican veteran of ’93 . . . a man of ninety years, holding his ammunition bag (possibly used for begging), dressed in old white linen cloth made out of patches and a visored cap. He looks down at the romantic cast-offs at his feet (he is pitied by the Jew).

Next come a hunter, reaper, strong-man, a clown, a textile peddler, a workman’s wife, a worker, an undertaker, a death’s head on a newspaper, an Irish woman suckling a child, an artist’s dummy.

The Irishwoman is another English product. I encountered this woman in a London street; her only clothing was a black straw hat, a torn green sheet, and a frayed black shawl under which she was carrying on her arm a naked baby.

The cloth peddler presides over all of this; he displays his finery to everyone, and all show the greatest interest, each in his own way. Behind him, lying in the foreground are a guitar and a plumed hat.

Then comes the canvas on my easel with me painting seen from the Assyrian side of my head. Behind my chair is a nude female model. She is leaning on the back of my chair to watch me paint for a moment; her clothes are on the floor in front of the picture and there is a white cat near my chair.

Following this woman come Promayet with his violin. . . Then behind are Bruyas, Cuenot, Buchon, Proudhon.

In the foreground is a woman of the world and her husband, both luxuriously dressed.

Then toward the extreme right sitting on the edge of a table is Baudelaire reading a large book.

Courbet deliberately withholds information about the hidden meaning of the allegory in The Artist’s Studio. He constantly drops broad hints about its existence, teasing the reader-viewer. After his enumeration of every item in the picture in his letter to Champfleury, he concludes, “I have explained all this very badly, the wrong way round. . . I ought to have begun with Baudelaire, but it would take too long to start again. Make it out as best you can. People will have their work cut out to judge the picture—they must do their best.”

Several art historians have written about The Artist’s Studio. Here are some examples of these writings:

In 1977, during a Louvre exhibition celebrating the anniversary of Courbet’s death, curator Hélène Toussaint made an interpretive breakthrough: she discovered that the figures on the left represent actual historical personalities (“Le dossier de L’Atelier de Courbet,” in Courbet (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1977), 241-77):

Starting in the left foreground, Napoleon III is seated with two of his ministers. Seated to the emperor’s right is the “purveyor of cheap textiles,” representing Minister of Interior, Jean Gilbert Victor Fialin, duc de Persigny.

Opposite Persigny is a renegade republican named Émile de Girardin, whom Courbet referred to as “the coroner.” Behind him is Emperor Lazare Carnot, who voted for the execution of Louis XVI in 1792 and became the Minister of Interior under Napoleon I.

Next to him in a white uniform is the Italian chasseur, wearing the red scarf of revolutionary armies, and then Lajos Kosuth with a bonnet, representing Hungarian rebels. Tadeusz Kościuszko, holding a scythe, represents the Polish freedom fighters.

Between Persigny and Girardin is a carnival strongman symbolizing Turkey, and a jester in Chinese costume symbolizing European ties with the Far East. Behind Girardin is a young woman who represents an allusion to Greece.

Beneath the life-size lay figure crouches a woman to whom Courbet referred to as an Irish woman, dressed in rags and suckling her baby as an embodiment of poverty.

Crucial to Toussaint’s interpretation is the fact that the painting was executed for the Paris World Fair, which opened on May 1, 1855. Courbet surrounds himself with Bonapartists, socialists, Frenchmen, and foreigners to symbolically demonstrate the possibility of a peaceful coexistence of diverse opinions and stances. At the time, France was involved in a state of war. On June 2, 1853, the French fleet was dispatched to the Dardanelles, a narrow strait in northwestern Turkey. On March 27, 1854, Napoleon III declared war on Russia. On June 26, 1854, Greece was occupied by British and French troops.

The Artist’s Studio also includes a lament, a symbol of hope to abolish poverty, embodied by the mother in rags at the emperor’s feet. The painting contains a warning. Louis-Napoleon had published the book The Extinction of Pauperism in 1844 but it had by no means been fulfilled. On the floor lies a dagger pointed toward the emperor but still in its sheath. The revolutionaries in the background, including the chasseur and faucheur (scyther), wait passively to see what direction the emperor’s policy will take.

In the centre of The Artist’s Studio, Courbet has portrayed a nude model, a little boy, a white cat, and Courbet himself, in the act of painting a landscape. Margaret Armbrust Seibert suggests in “A Political and a Pictorial Tradition Used in Gustave Courbet’s Real Allegory” (Art Bulletin, 65, no. 2 (June 1983): 311-316) that Courbet has reassembled the traditional image of a painter, nude, model, little boy, and cat, as exemplified by Allegory of Sight and of the Art of Painting (An Artist and His Model), created by Dutch artist Johann Saenredam (1565–1607) after Hendrik Goltzius (1558–1617). The resemblance between the two works does not mean that Courbet saw Saenredam’s work; rather, it represents the continuation of a tradition. Differences between Courbet’s painting and the print raise questions regarding Courbet’s recasting of this traditional emblem in a “realist” mode. The boy—an ordinary child, not an angel or putto—is a reference to the unspoiled future generation. Alternatively, he could be a metaphor for Courbet’s own sincerity, truth, and naiveté. The model, casting her clothing aside, represents beauty and truth. Thus, the child and model create an effective bracket around the artist at his easel.

Siebert also discusses the origins and Republican use of the white cat as an emblem of Liberty.

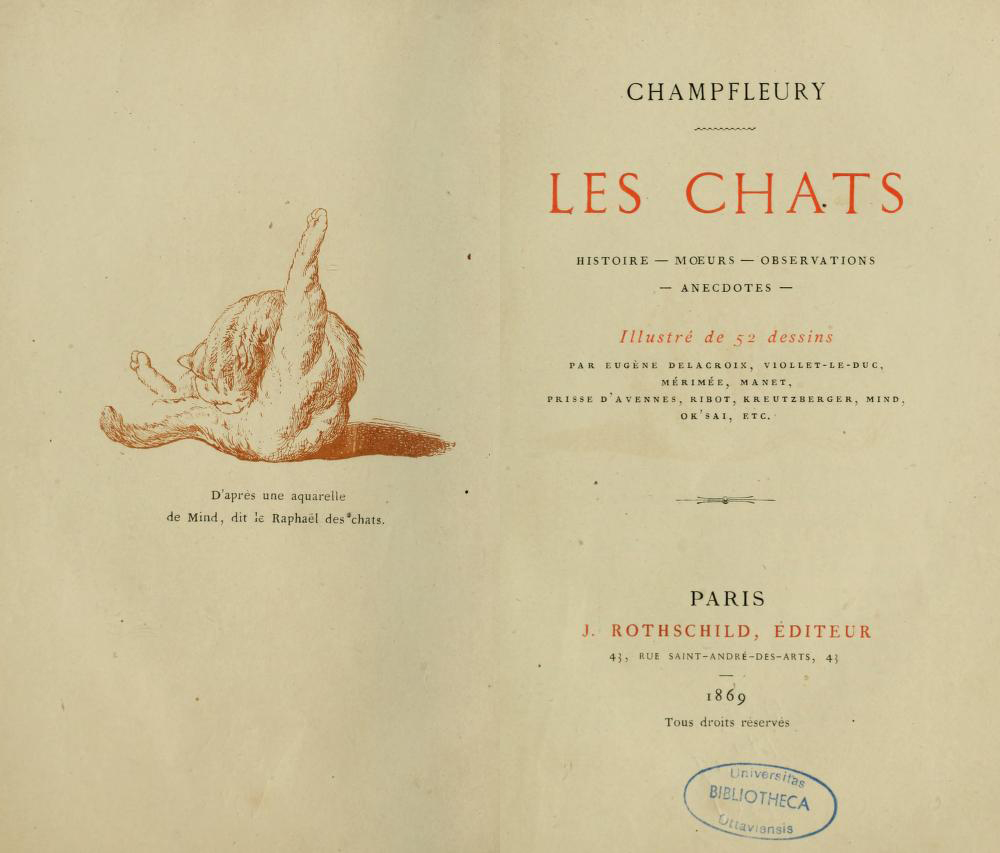

In 1848 Theophile Gautier published an article on Republican symbolism in L’artiste. This article specifically cites in its text the iconologies of Ripa, and Gravelot and Cochin. Similar information also appeared in Champfleury’s Les chats: “The origin of the cat as a symbol of independence is of remote antiquity. In the temple of Liberty which Rome owed to Tiberius Gracchus the Goddess was arrayed in white … at her feet was a cat, the emblem of Liberty. From the Middle Ages down to modern times we repeatedly find the cat used as a symbol of independence.” Some of the examples cited in Champfleury employ the cat alone as a representative of independence, and special mention is made of its uses as an emblem of the French Republic by both Gautier and Champfleury. The cat became a part of the Republic’s coat-of-arms and appeared at the feet of Liberty in Pierre-Paul Prudhon’s Allegory of the Constitution, a detail of which appeared in Champfleury’s Les chats. The white cat in Courbet’s Atelier follows the dictates that Liberty be draped in white, reinforcing the fact that this is her cat, Independence.

Amanda M. Guggenbiller writes in “Compositions of Criticism: A Reinterpretation of Gustave Courbet’s Paintings of Nudes” (M.A. Thesis, West Virginia University, 2014):

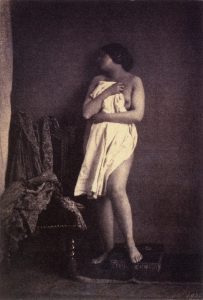

Courbet mentioned in a letter to Alfred Bruyas dated December 1854 that he would like Bruyas to send him ‘that photograph of a nude woman about which I have spoken to you. She will be behind my chair in the middle of the painting…Send me as soon as possible the two profiles and the photograph of the nude woman.’

The profiles that Courbet said he wanted sent to him were a side profile side of himself and another of Bruyas, which would be used in The Artist’s Studio from 1854-1855. This request to have the two profiles and the photograph of the nude sent at the same time, and the manner in which Courbet said he would place the nude female within the composition, matches the figures in The Artist’s Studio. There is no clear indication that lists exactly what photograph Courbet mentioned, but Aaron Scharf argues that the source of the photograph was from Vallou de Villeneuve, a proposal that has been widely accepted by Courbet scholars. The photograph that has the most similarities was registered in 1853, almost ten years prior to the painting being created.

To avoid being accused of photographing pornographic scenes or for illicit purposes, nude photographs were required to be registered as academies or artist’s models. Courbet used photographs that were registered under this subject as well.

Linda Nochlin writes in “Courbet’s Real Allegory: Rereading “The Painter’s Studio” (in Courbet Reconsidered, Sarah Faunce and Linda Nochlin, eds. Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum, 1988):

For me… the Irish beggar-woman constitutes not just a dark note of negativity within the bright utopian promise of the allegory of The Painter’s Studio as a whole, but rather, negates such promise as a totality. The poor woman – a dark, indrawn, passive, source of melancholy within the painting as well as a reference to it outside its boundaries – constitutes both a memorial to melancholy past and the repressed that returns, turning against both the triumphant harmony of Courbet’s allegory, interrupting the flow of its intentional meaning. In short, to me, reading as a woman, the beggar-woman sticks out like a sore thumb. In her, the would-be allegorical connection between thing and meaning is really fumbled… Embodying in a single figure the convergence of gender and class oppressions, the Irishwoman for me becomes the central figure, the annihilation-cancellation of Courbet’s project, not merely a warning about its difficulty. Figuring all that is unassimilable and inexplicable – female, poor, mother, passive, unproductive but reproductive – she denies and negates all the male-dominated productive energy of the central portion, and thus functions as the interrupter and overturner of the whole sententious message of progress, peace and reconciliation of the allegory as a whole. In my rereading of Courbet’s The Painter’s Studio, the Irishwoman as a figure, refuses to stay in her place and act as a mere vehicle of another more general meaning, be it Poor Ireland or the Problem of Pauperism, an incidental warning signal on the high road to historic reconciliation. In her dumb passivity, her stubborn immobility, she swells to the dimensions of an insurmountable, dark, stumbling block on that highway to constructive progress.

Sophie Rachel Handler writes in “Shadows of Childhood: The Emergence of the Child in the Visual and Literary Culture of the French Long-Nineteenth Century” (PhD diss., Durham University, 2017):

The small boy drawing on the right of the canvas and that of the young child in the centre who observes the artist, are significant considering what they inform us of Courbet’s own view of children, childhood, and their relationship with creativity. During the Enlightenment and Romantic eras childhood began to be discovered as something of a cache of wisdom, insight, and sensitivity. this association of childhood intuitiveness with a sort of ‘creative vitality’ was gradual, and began in earnest early in the nineteenth century, when the innovative potential of the child emerged, unbound by habit or regulation, as an influence upon avant-garde endeavours.

In light of this, we may consider the small boy scribbling away in Courbet’s Studio, half submerged in shadow, emerging from the darkness around him, as symbolic of the capacity of the ‘wise child’, unencumbered by instruction or influence, to draw us out, in both senses, from the dark opacity of art defined by Academic rigour, and genuinely enlighten us with the clarity of his unfettered, inner vision. Courbet sought in this painting to reveal the capacity of the child to create before the intrusion of adult influence, symbolised perhaps by the dwarfing of the child by the engulfment of dark adulthood.

The child is free-drawing. This is reflective of a deeply liberating approach to artistic creation related to free-writing, buttressed by the interchangeable use of the French term écriture for writing, handwriting, and the artist’s brushstrokes, Courbet’s child is demonstrative of the possibilities when one truly submits oneself to the impulses and direction of nature as opposed to the societal influences around him.

Moreover, Baudelaire in “Morale du joujou” published in 1853, devotes an essay to the analysis of spontaneous creativity of children in relation to their toys. He-goes so far as to maintain that genius nothing but “l’enfance retrouvé è la volonté.” The figure of child, only person engaged in some sort of artistic pursuit closely connected with advanced aesthetic theories of time–paying homage to spontaneity and creativity of child and has own creative vigour, an “ignorance voluntary” and childlike directness of approach to painting.

Petra Ten-Doesschate Chu writes in “Showing Making in Courbet’s The Painter’s Studio,” (Hiding Making – Showing Creation: The Studio from Turner to Tacita Dean, edited by Rachel Esner et al. (Amsterdam University Press, 2013), 62–72):

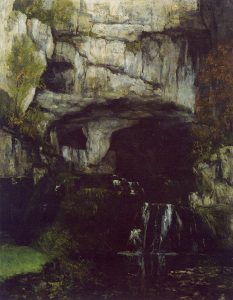

While Courbet’s depiction of himself painting a Franche Comté landscape inside his Paris studio may be a reference to his well-known ability to paint “magnificent” and characteristic landscapes from memory, it may also represent his common practice of laying in his landscapes outdoors and finishing them later in the studio.

The sculptor Max Claudet, in his account of the genesis of Courbet’s painting of the Source of the Lison River, ca. 1864-1866 (probably the version in the Galerie Paffrath in Düsseldorf, Germany), reports that to paint the picture Courbet went to the site, carrying with him a canvas that was about one meter tall. Claudet tells us that Courbet executed this painting outdoors, directly in front of the motif. He carried with him a box containing four jars of paint — white, red, yellow, and blue. Courbet mixed these colors on the palette and then, using his palette knife, applied the paint to the canvas, scraping it on with firm and determined motions. Claudet recounts with astonishment that it took Courbet less than two hours to finish the painting. “We were stunned by that speed of execution! Barely two hours of work to cover a one-meter canvas.” Though to Claudet, Courbet’s painting looked finished, to the artist it was not. Courbet would subsequently complete it in the studio, working with brushes rather than the palette knife. Indeed, the numerous contemporary accounts about Courbet’s rapid execution of his landscape paintings, such as the accounts by Claudet and Castagnary above, are in contradiction to the complex, highly ‘worked’ surfaces of Courbet’s landscapes. These suggest that, back in the studio, Courbet belaboured the rapidly done lay-ins, executed largely with the palette knife, to create the rich surfaces for which Courbet’s best landscape paintings are known.

It appears, then, that Courbet, working either outdoors or from memory, quickly massed in his landscape paintings with the palette knife. In so doing, he achieved such an impression of completeness that his contemporaries often thought of the lay-ins as finished paintings… The artist may well have encouraged this impression, as it helped him to build an image as a virtuoso artist, a painter-magician. However, it would seem that, in reality, the completion of the work took place in the studio, perhaps in numerous sessions.

A photograph of Courbet’s studio on the route de Besançon in Ornans, made by Eugène Feyen in 1864, shows several paintings leaning against chairs in the center of the room, suggesting that the artist may have worked on them simultaneously, touching up one as another was drying.

Baillère, who visited Courbet’s studio several times between 1865 and 1866, described it as follows:

Instead of being filled with bibelots, like the studios of fashionable painters, the studio of Courbet was decorated only by the master’s paintings. They were everywhere, hung on the walls from the baseboard to the ceiling, on easels, several were stacked against the platbands.

His description was confirmed by Zacharie Astruc, who described Courbet’s studio as “full of canvases [emcombré de toiles],” and Castagnary, who wrote that the studio was submerged under an avalanche of paintings.

Despite the apparent emphasis in Courbet’s painting on showing creation, the artist is in no way hiding making. On the contrary, he is making a show of it for the group of critics and collectors on the right side of the painting who seem to have come to see him paint.

His virtuosity with the palette knife and the brush, as well as his ability to work from memory, were qualities of Courbet’s work that were much praised in his time and that drew people to his studio to watch him perform… Perhaps The Painter’s Studio, that “real allegory,” may be said to show creation as well as making.

It is undoubtedly true that Gustave Courbet coveted attention and courted controversy throughout his career. He was the quintessential spectacle artist. For all his anti-market sentiment, he cultivated a brand name for himself by embracing the popular press and the gossip machine. He had a vain and rebellious nature which for a time served him well. Initially, he promoted his provincial ‘difference’ as a homme du peuple, often holding court and speaking loudly in his Franche-Comte patois. His assumption of infamy, his rejection of the academy and the haute bourgeoisie as his primary audience, and his depiction of the lower classes as noble, contemporary heroes placed him at the head of the artistic avant-garde. At the height of his fame, he refused to sell his work to high-ranking government officials, and when offered the cross of the Legion d’honneur by Napoleon III, in 1870, he loudly declined, a controversial decision that was widely publicized, generating more attention than any publicity surrounding the honour would have.

Courbet’s involvement in politics was undertaken with the same drive and bravado. But his role in the toppling of the Vendome Column (to be discussed in the next chapter) during the revolutionary Paris Commune brought incarceration for six months and financial ruin. When his assets were sequestered in France, he fled to Switzerland, where he died in exile at age 55.