Chapter Two

ÉDOUARD MANET &

Modern Life

CONTENTS

Introduction

2.1

The Challenge of the New: Modernist Attitudes and the Académie

2.2

Enter Édouard: The Paris Salon of 1859

2.3

The Perfect Storm: Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe, the Paris Salon and the Salon des Refusés

2.4

2.5

The International Exposition of 1867

2.6

The Political Manet: The Execution of Emperor Maximilian

2.7

Portrait of Émile Zola: Japonisme and the Influence of the Multiple

2.8

2.9

2.10

Impressionism and its Contexts

INTRODUCTION

Édouard Manet forged a path for a revolutionary aesthetic movement in Western art history. During France’s Second Empire a shift in the socio-economic order coincided with the rise of cultural modernity and an embrace of innovatory attitudes and ideology. The emergence of a new leisure class, the effects of a modernized Paris, and the development of visual technologies significantly impacted the cultural landscape, and it would go on to affect the production, dissemination, and acquisition of art.

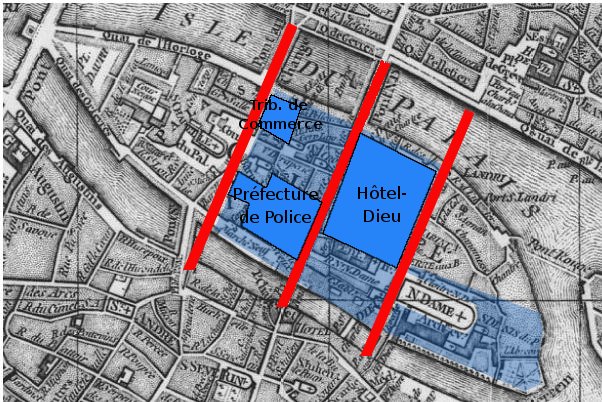

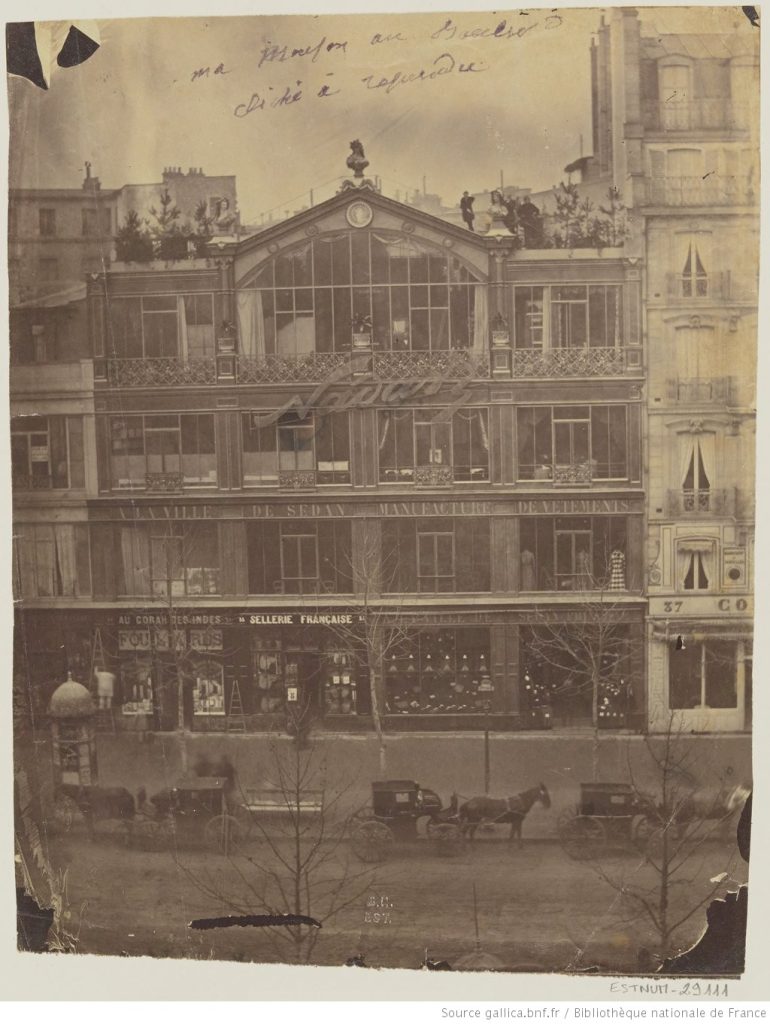

Cultural modernity was significantly impacted by the reconstruction of Paris as a new metropolis. In the years leading up to l’année terrible of 1870-1871, (the Franco-Prussian War and Paris Commune) Napoleon III set out to rebuild the sections of the city destroyed by the revolutions of 1789, 1830, and 1848. His visionary project was undertaken by Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann, whose ésprit de géometrie transformed the old medieval city with its narrow streets and slums into a network of large, lighted boulevards flanked by apartment buildings for the newly minted bourgeoisie.

Haussmann created an extensive municipal park system, built schools and hospitals, and installed gas lines and an advanced underground sewer system. These massive changes to the built environment transformed social life, facilitating urban mobility and creating new spaces for social interchange.

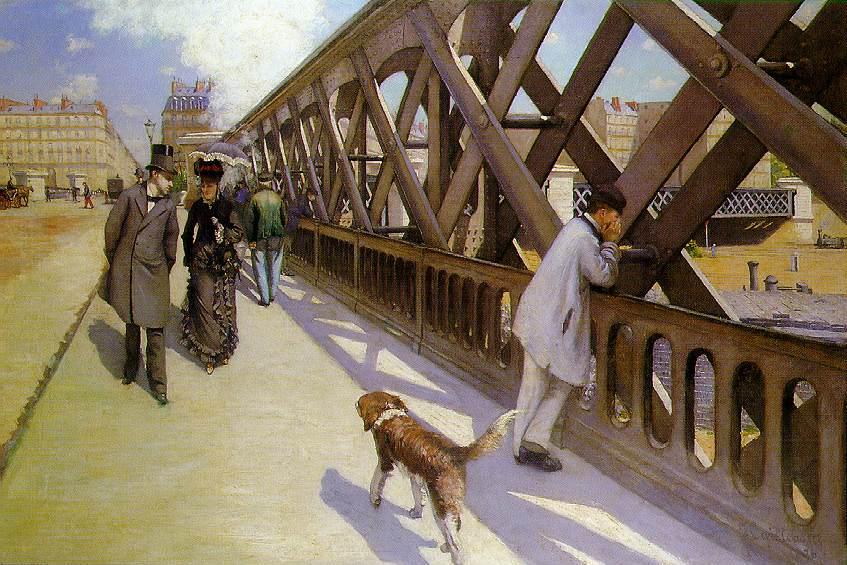

The social effects of “Haussamanization,” the peopled open boulevards, avenues, and parks, as well the visual stimuli of shop vitrines, murals, and advertising bill posts, gave rise to a culture of spectatorship amongst a newly affluent demographic of city dwellers.

For Manet, the quintessential flâneur, an inclination towards observing contemporary city life was ignited by the writings of the poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire. In his 1864 essay, “The Painter of Modern Life,” Baudelaire emphasized that the artist’s duty was to encapsulate the essence of the “fleeting, ephemeral experience of life in an urban metropolis.” This philosophy profoundly influenced Manet’s artistic perspective, inspiring him to portray the dynamic and transient aspects of modern urban existence in his works.

Manet’s fascination with modern life as a subject found a precursor in Gustave Courbet’s provocative depictions of rural realism. However, while Courbet portrayed the unvarnished reality of an essentially unaltered peasant world, Manet’s modernism was distinctly urban and forward-looking. He departed from the distant historicism of academic art, opting instead for contemporary experiences and pioneered stylistic innovations that broke with tradition. Alongside fellow avant-garde artists, he looked outward, embracing emerging art technologies such as print reproductions and multiples and drew inspiration from non-Western aesthetics, notably Japanese art and design. This collective engagement with diverse influences marked a departure from conventional artistic norms.

In this chapter, we will delve into the attitudes and values that shaped Manet’s artistic journey, exploring the impact of social structures and political events on his art practice. Additionally, we will explore the motivations that gave rise to the early stages of modernism, a movement which challenged the established academic canon and played a pivotal role in altering the trajectory of modern art.

2.1

| The Challenge of the New: Modernist Attitudes and the Académie

The battle between modernist artists and the arch-conservative Académie intensified during Napoleon III’s Second Empire (1852–70), playing out publicly at the prestigious annual Paris Salon. As the only official venue for the exhibition of art in Paris, the historic Salon was of vital importance to living artists. It offered direct public visibility and media coverage as well as access to lucrative state commissions and, later, to a new cohort of bourgeois buyers wishing to collect art for their homes.

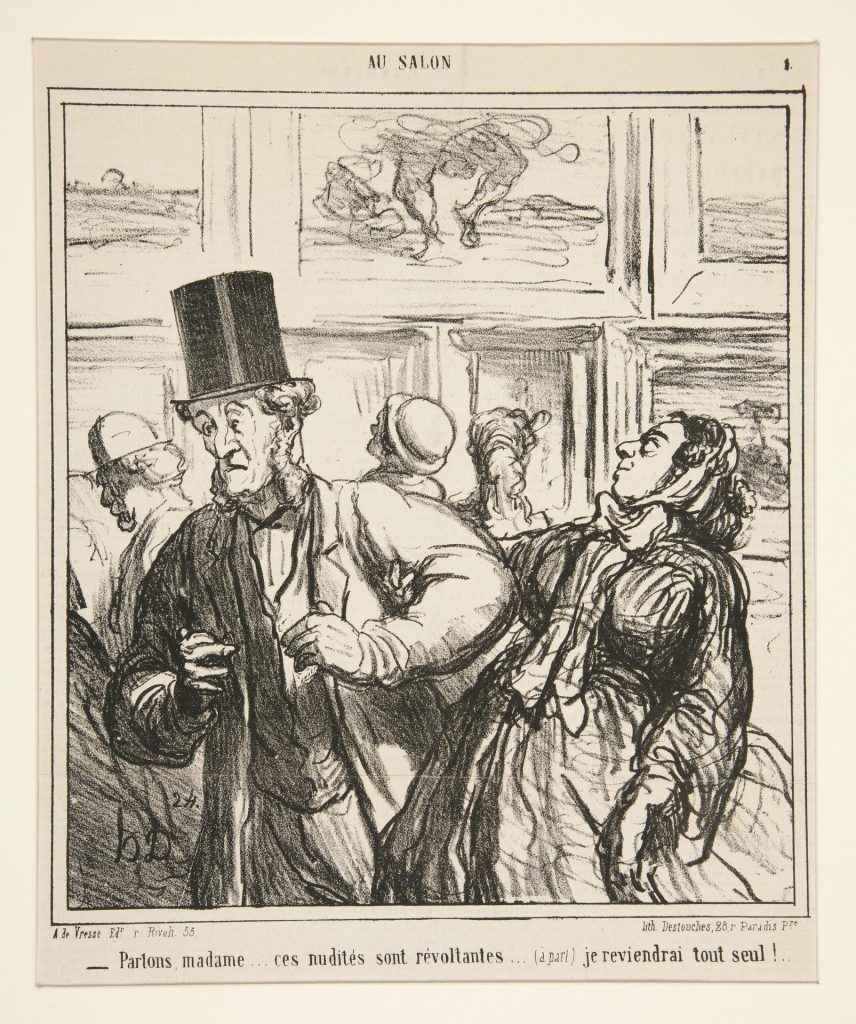

Sponsored by the French government and the Académie des Beaux-Arts, the Salon had dictated taste in art since its inception at the Louvre Museum in 1667, where it continued to be held until the Revolution of 1848. In 1857 the high-status event was relocated to the newly built Palais de l’Industrie on the Champs Elysées. Exhibitions were juried by Académie officials whose mandate was to promote France’s so-called ‘new’ art, which favoured academic classicism and historical subjects. While it aimed to encourage the enjoyment of art and hone skills of connoisseurship in its viewers, the jury sought to mould public taste in line with its selections and to discourage the exercise of insurgent social ideas. Originally exclusive to students and teachers at the Académie royale, by the nineteenth century, the Salon had expanded its acceptance criteria to French and foreign non-academicians, thereby enlarging its influence as the arbiter of style throughout Europe.

Jules-Antoine Castagnary, a French politician, journalist, critic, and staunch supporter of Courbet’s Realism, critiqued the hegemony of French Salon painting during the Second Empire. While Salon exhibitions comprised a variety of stylistic tendencies: history painting, historical genre, Orientalist, eclectic, academic, Classicist, Romanticist, Naturalist and Realist, the vast majority of art on view aligned with traditional art, which in turn was equated with national greatness. In “The Triumph of Naturalism,” Castagnary observed that state-sanctioned art was dominated by the genres of landscape and portraiture and could be roughly divided into three stylistic categories: Neoclassicism, Romanticism and Naturalism. He decried the Neoclassicist and Romanticist stranglehold on academic art, championed Realist and Naturalist painters, and called for artists to depict events of their own time (“Salon de 1863, Les Refusé,” Le Courier du Dimanche, June 14, 1863, 4-5). In 1867 he again urged artists to paint the “modern spectacle,” stating, “What need is there to go back through history … to examine the registers of the imagination?” … “beauty is in front of the eyes, not inside the brain; in the present, not in the past … The universe we have here, before us, is the very one that painting ought to translate.” (“Salon of 1867,” in Salons (1857-1870), (Paris: 1892), vol. 1, 241-242)

The paintings of Jean-Léon Gerome are an example of art popularized by the Academy. Gerome favoured subjects derived from antiquity, and he employed precise drawing techniques and meticulously rendered physical gestures and facial expressions to articulate those subjects. His carefully constructed compositions and fine finishes were entirely consistent with academic Neoclassicism. Death of Caesar, for example, displays a faithful observance of the rules of anatomy, perspective, modelling, and physiognomic expression.

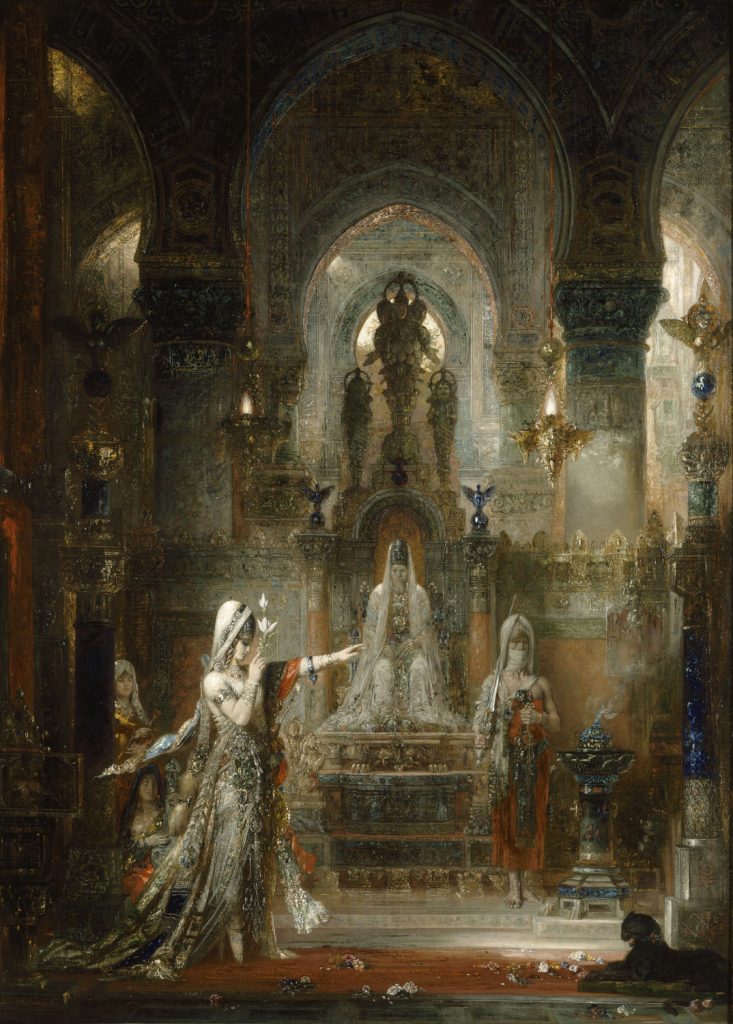

Castagnary also critiqued contemporary artists who continued to work in an ‘irrelevant’ Romanticist vein, idealizing nature, glorifying the past, and embracing excessively emotive narratives. These artists included Léon Bonnat, Fantin-Latour and Gustave Moreau, each of whom was inspired, to a lesser or greater extent, by Eugène Delacroix, the acknowledged leader of French Romanticism.

Moreau was the quintessential painter of allegory and myth. His Salome illustrates Romanticism’s penchant for the exoticism of a fictional eastern world, which he mystified further by applying painterly veils of glaze and paint. Moreau’s highly detailed illusions stood in contradiction to Courbet’s raw Realism and Naturalism’s directness of approach.

Despite the enduring dominance of Classicism and Romanticism, the Naturalist school was recognized as a new direction for Salon painting. Ironically, Naturalism, while breaking away from traditional styles, served as the direct precursor to one of the most contentious movements of the late nineteenth century: Impressionism.

Naturalism sought to depict the natural world with sympathetic accuracy. It had its roots in the plein-air painting of the Barbizon group of landscape artists who worked around the Forest of Fontainebleau near Paris. Their ambition to paint nature in situ challenged the idealized pastorales popular at the Salon. The Barbizon group included Narcisse-Virgile Diaz de La Peña, Jules Dupré, Théodore Rousseau, Constant Troyon, Charles-Émile Jacque and Jean-François Millet. Rousseau and Millet, the pioneering leaders, lived in the village of Barbizon.

The term ‘Naturalist’ carried a profound significance, embodying a new principle of equality and individualism in both society and culture. Castagnary emphasized that Naturalism “springs from our politics which, by taking the equality of individuals and the equality of conditions as a desideratum, has banished from the mind false hierarchies and lying distinctions.” This statement establishes a clear connection between Naturalist art and democratic politics.

Rousseau’s “Forest of Fontainebleau” exemplifies the unfiltered, directly felt experience of observing the natural world. The painting, featuring beloved oak trees dominating a late afternoon scene, captures diffused light dappling on a thinly painted pond, tree branches, a single figure, and a herd of cows. Similar to other artists of the Barbizon school, Rousseau initiated the composition on-site, using chalk and thin layers of medium, and later completed it in the studio.

Although Rousseau and Millet held considerable appeal, it was the traditionalist artists like Jules Breton who garnered favor with patrons and jurors during the mid-1800s. Breton, known for his peasant themes, skillfully integrated idealized narratives of Classicism. His works often portrayed the perceived superiority of ruling notables and conveyed a moral endorsement of proletarian subservience.

Erecting a Cavalry depicts peasants watching a passing religious procession, a representation of the tripartite governing authority: the Church (priest), Commerce (bourgeoisie in suits) and the State (the uniformed gendarme). The work is a realistic portrayal of an event Breton would have witnessed in his youth and is made more meaningful through the inclusion of his wife Élodie de Vigne, who appears twice: as the mother holding the hands of her two children and as the girl in white carrying the crown of thorns on a cushion.

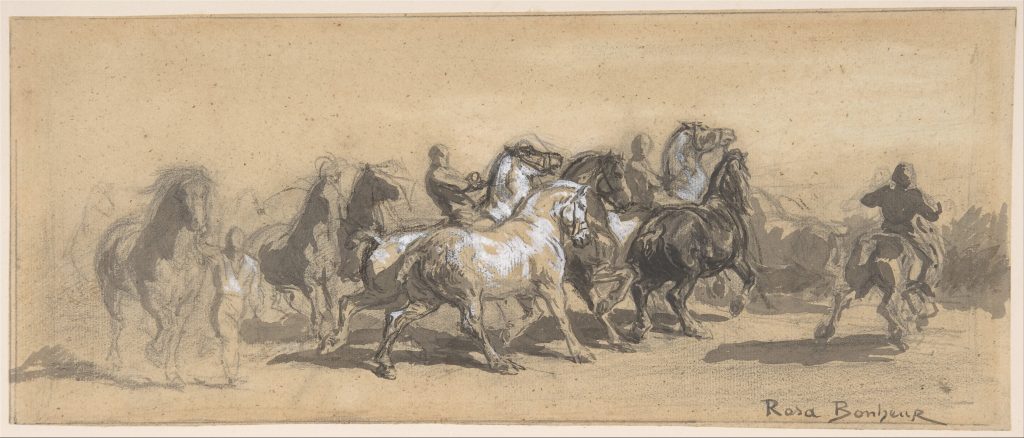

The monumental artwork Horse Fair captures the scene of several Percheron horses being showcased to potential buyers at the horse market near Salpetriere. This striking image draws inspiration from both the Parthenon marbles in London and the artistic styles of Romanticists Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix. Exhibited at the 1853 Salon and the 1855 Exposition Universelle, the painting garnered widespread praise for its evocative depiction and artistic prowess.

Horse fairs were common in nineteenth-century Paris, but the captivating power of Bonheur’s interpretation lies in the work’s epic, even cinematic, composition and the individuality she assigns each animal. The work’s monumental scale (eight feet high and sixteen feet long) allows for a close-up view of Bonheur’s anatomic precision and brings one closer to the horses portrayed. Each animal is unique in physiognomy and dynamic movement. Bonheur effectively shows their muscles coiling, hooves kicking, and manes flying. The horses twist and turn within the frame, straining against their bonds or rearing to buck their riders as handlers corral them. The handler wearing a blue shirt in the centre of the painting and looking directly at the viewer is probably a self-image of the artist.

When Bonheur initially approached the French Minister of Fine Arts to secure an official painting commission, the response she received was that the chosen subject demanded a more experienced artist. Undeterred by the dismissal, Bonheur chose to ignore the slight. Instead, she devoted the following eighteen months to visiting the horse market on the Boulevard de l’Hôpital where she diligently drew the subjects she loved and felt confident in portraying in paint.

Rosa Bonheur, wearing the Legion of Honour, 1865. View Source

Rosa Bonheur was lesbian or transgender and had two consecutive long-term relationships with women. Kittredge Cherry writes in the online posting “Rosa Bonheur: Cross-dressing painter honored ‘androgyne Christ’” that more recently “she has been celebrated as a queer pioneer, feminist icon, and role model for the LGBTQ community.” Though originally of Jewish origin, the Bonheur family adhered to Saint-Simonianism, a Christian-socialist sect that promoted women’s education alongside men. Bonheur, in her private and professional life, was motivated by the desire to celebrate a new sense of “matrimony”—not the ceremony sealing the subjection of a woman to a man according to the Code Civil—but in a pointed rejection of the patriarchal institution, “matrimony” as marriage between independent, financially autonomous women who freely choose to join their lives, who will live, love and work together for their mutual happiness and professional advancement.

Indeed, although not considered an avant-garde artist because of her traditional painting techniques and devotion to animal paintings, she was avant-garde in her ideas, behaviour, and determination to overcome conventions unacceptable to society.

It was within this context of cultural modernization and contested aesthetic reforms that avant-garde artists emerged in Paris in the 1860s. Working against traditional norms, faced with rejection, hostility and ridicule, they pressed forward for inclusion in the Paris Salon, the premium venue for the cultivation of critical and public attention.

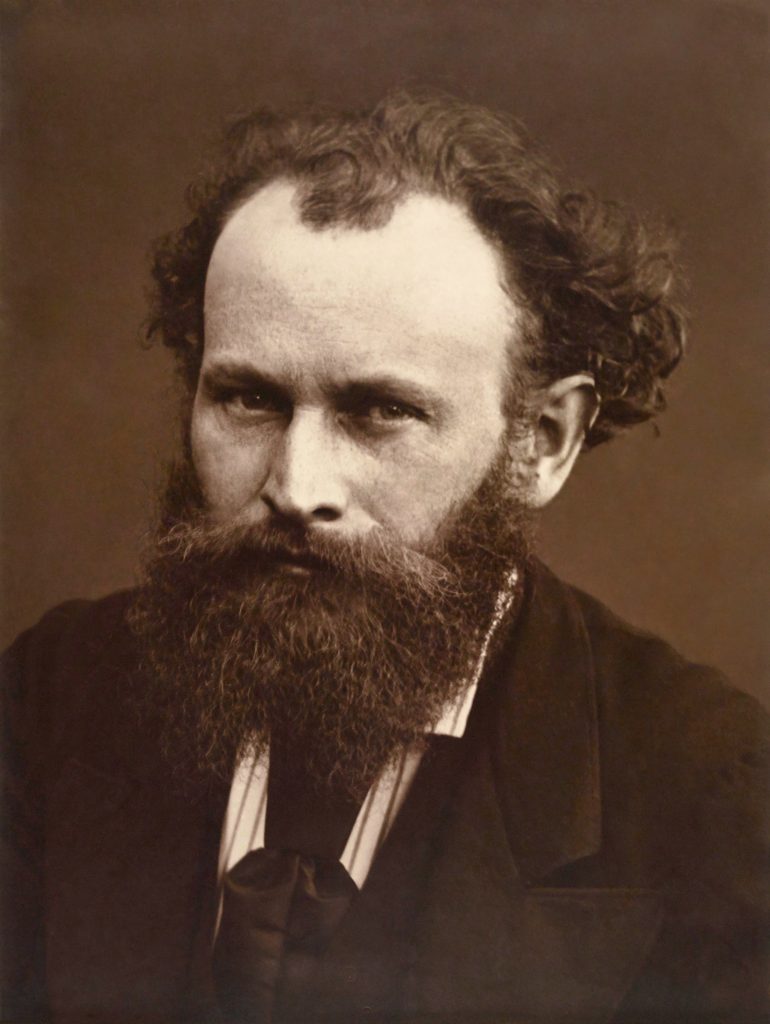

2.2

| Enter Édouard: The Paris Salon of 1859

Édouard Manet led a generation’s break from the stranglehold of state art. Born to an upper-middle-class family in Paris, his father, Auguste Manet, was a judge, and his mother, Eugénie-Désirée Fournier, was the daughter of a diplomat and the goddaughter of the Swedish crown prince Charles Bernadotte. Manet rejected a legal profession, opting instead to train for a post in the Navy. After failing the naval examination twice, his father agreed to sponsor his art education. From 1850 to 1856, Manet studied with the French history painter Thomas Couture, who taught him the fundamentals of drawing and traditional painting techniques.

The influential late twentieth century sociologist and anthropologist Pierre Bourdieu, argues in Manet: A Symbolic Revolution (Polity, 2017), published after his death, that Manet’s habitus was fundamentally shaped by his education – an education uniquely hybrid in nature, as it provided elite art historical knowledge while cultivating the artist’s revolutionary aesthetic interests. Although his instruction was academic, his mentor Thomas Couture sought to mediate between the “high” subjects of the academy and the “low” subjects of modernity, imparting upon Manet an inclination for dissent that would soon send Paris’s art world into an uproar.

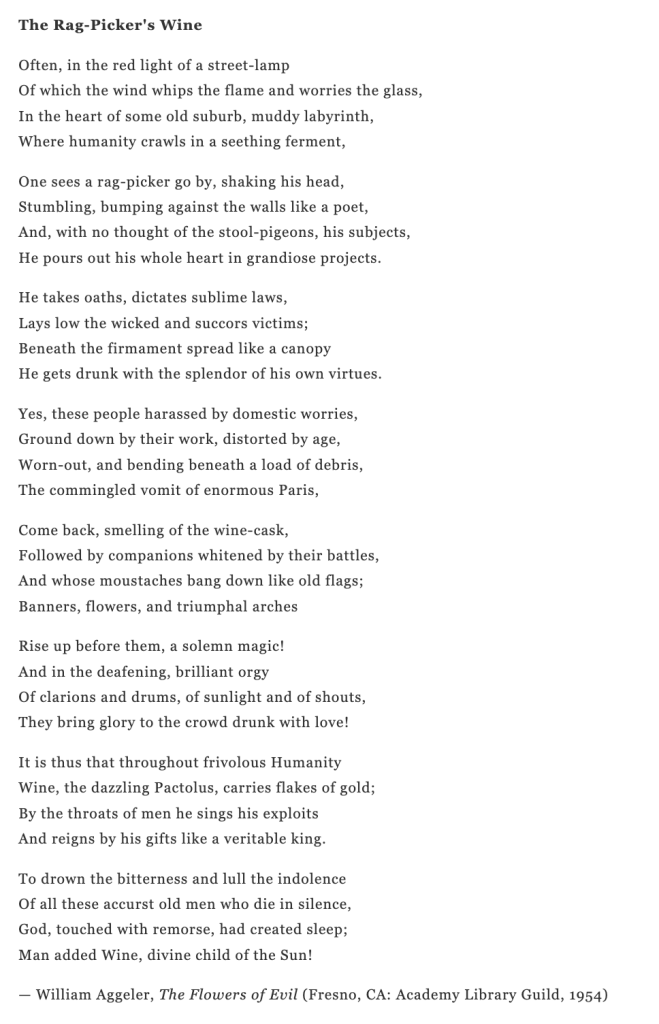

The Absinthe Drinker sparked Manet’s first controversy at the Salon of 1859. It was flatly rejected by the jury (except Delacroix), and he was castigated for the unapologetically realistic portrait of a “low-life” Manet’s subject was a chiffonnier or ragpicker by the name of Collardet, who was often seen loitering around the Louvre collecting scraps, along with other unemployed scavengers. Manet’s life-size portrayal of the city ragpicker served to put on display Louis Napolean’s failure to address the reality of urban poverty.

Here, the disheveled figure draped in a worn cloak and donning a stovepipe hat assumes a dandified pose, rendered absurd by the conspicuous bottle of alcohol lying at his feet. Yet, his demeanor stands in stark contrast to that of a typical ragpicker labouring through the streets burdened by a bag of rags. Instead, his attitude reinforces the perception among bourgeois Salon-goers that the slums represented strongholds of revolutionary resistance. Additionally, the figure hints at the idea of the artist as a marginalized urban outcast, finding inspiration in the streets. This conceptualization may also suggest that by aligning with the rejection experienced by the ragpicker from society, the modern artist envisioned his own liberation from class identity.

Manet maintained a friendship with the poet Charles Baudelaire, a proponent of paintings depicting modern life and a staunch advocate for Realism. Manet was deeply committed to portraying the real world through a contemporary lens. He sought to capture the essence of modern life without succumbing to the restrictive conventions of academic style and subject matter.

The presence of alcohol in The Absinthe Drinker references the habits of Baudelaire’s protagonist, “stumbling and bumping against the walls like a poet,” in Les Fleurs du Mal, first published in 1857. According to Baudelaire, the experience that ought to count for an artist is the personal experience of solitude, isolation stemming from poverty, alcoholic addiction, and nights in a big city. Baudelaire proposed the linkage between intoxication and an authentic experience of modernity on several occasions.

The convergence of efforts to democratize art, a surge in the number of practicing artists flocking to Paris, and the Académie’s decision to open its exhibitions to outsiders created a perfect storm. In 1863, the situation was further aggravated by the rejection of two-thirds of the 5000 submissions to the Salon. Prominent artists such as Gustave Courbet, Paul Cézanne, Camille Pissarro, James Whistler, Henri Fantin-Latour, and Édouard Manet were among those spurned by the Salon. This pivotal moment marked a turning point in the art world, foreshadowing the rise of avant-garde movements and challenging the established norms of the time.

Amid growing protests against the autocratic and exclusionary regulations of the Académie, the state intervened. In response to mounting discontent, Napoleon III ordered the creation of an alternative exhibition space for the rejected works, known as the Salon des Refusés. In his statement, Napoleon III expressed the desire for the public to assess the legitimacy of the complaints, stating, “His Majesty, wishing to let the public judge the legitimacy of these complaints, has decided that the works of art which were refused should be displayed in another part of the Palais de l’Industrie.” This move by the state carried significant implications, suggesting official acknowledgment of ‘avant-garde’ art and recognition of the shortcomings of the Académie.

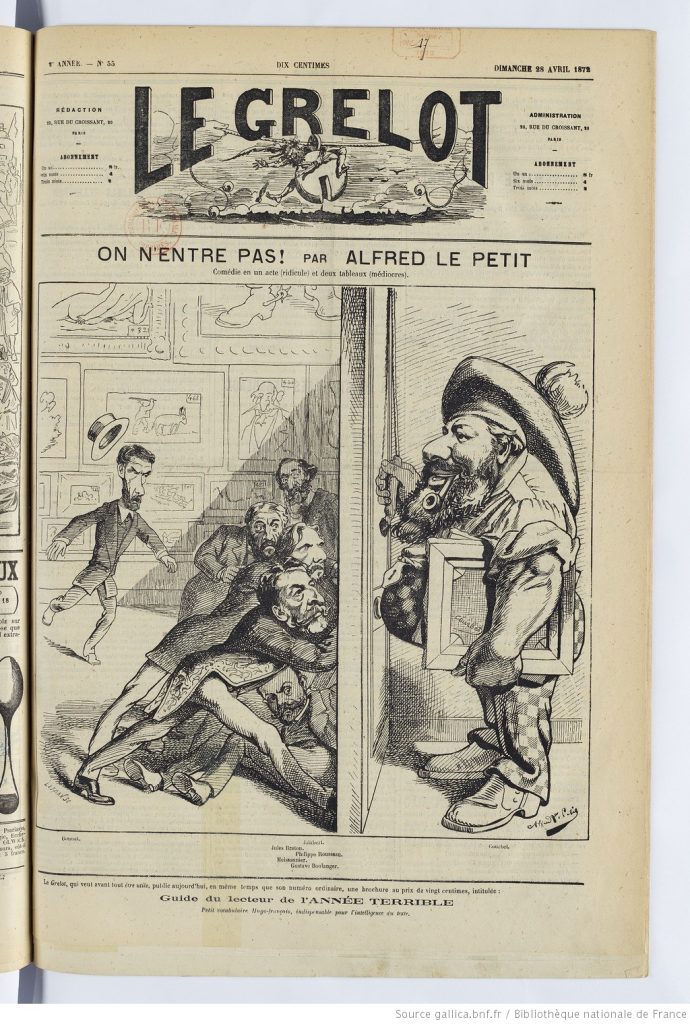

The Salon des Refusés featured approximately 800 works, with paintings comprising the majority. The critical response was largely hostile. While a few, like the writer Émile Zola, praised the event, many visitors, influenced by public and press criticism, attended only to mock. Despite the ridicule, the Salon des Refusés drew over a thousand curious spectators daily. This marked the beginning of the end for the official Salon’s dominance as a showcase and arbiter of aesthetic value.

The 1863 Salon des Refusés placed Manet in the spotlight for his controversial Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe ( Luncheon on the Grass). The viewing public (including Napoleon III ) was scandalized by the painting’s ‘immorality.’ The subject of Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe is a suburban luncheon in the park. It features two fully dressed men sharing a picnic with a naked woman while a second semi-dressed female is seen bathing in the background. The painting was decried as pure debauchery, its scandalous imagery made worse by the Manet’s bold stylistic approach and the recognizability of the naked woman and her entourage.

The trope of the female nude was traditionally idealized and mythologized. Here instead was a familiar naked woman, Victorine Meurand, gazing out at the viewer while relaxing in the Bois de Boulogne. It was a blatant recasting of classical iconography, a challenge to the established canons of representation. Dejeuner caused a furor, stigmatizing Manet as a radical and a menace to polite society.

The composition of The Luncheon on the Grass was a purposeful quoting of two 16th-century Italian works: The Pastoral Concert, an oil painting, and The Judgment of Paris, an engraving depicting a scene from Greek mythology.

Manet appropriated the figures in Dejeuner from The Pastoral Concert, an allegory of poetry and music inspired by pastoral poetry, a genre of prose originating with the idylls of the ancient Greek poet Theocritus that extoled the rustic world of the shepherd, and the beauty of the natural world. Shepherds playing music to muses and woodland nymphs was a common motif in pastoral poetry; The Pastoral Concert was a visual quotation of this genre.

The Judgment of Paris was also a reference for Manet ‘s The Luncheon on the Grass particularly the poses of the two river gods and the seated water nymph in the lower right-hand corner.

In the 1860s, Manet’s art was rejected by conservative critics for its unconventional brushwork, lack of perspective, and unfinished qualities, leaving the relationship of the artist to the depiction as indeterminate as possible. This “aesthetic gaze,” has been explained by Pierre Bourdieu as grounded in a rejection of an academic order, but is also derived from studying traditional images.

Michael Fried, in “Manet’s Sources: Aspects of His Art, 1859-1865″ (Artforum 7 (March 1969): 28–82), argues that a comprehensive account of Manet’s achievement must consider his relationship to other French artists, in particular Antoine Watteau, both to signal his “Frenchness” and to situate his art within a traditional context. Fried writes:

Dejeuner sur l’herbe (1863) is probably the most striking instance of the way in which references to specific works by other painters may obscure a less specific but possibly fundamental reliance upon Watteau. In the first place, the three foreground figures in Manet’s painting are a direct quotation from Marcantonio Raimondi’s engraving after Raphael’s Judgment of Paris. It is also known that Manet turned to Giorgione’s Concert champêtre for the most immediately controversial aspect of his painting, the depiction of two fully clothed men picnicking with two women one of whom wears nothing more than a kind of shift and the other of whom is (almost) wholly naked. But despite the specificity of these connections, the basic conception of the Déjeuner is far closer to Watteau than to either Raphael or Giorgione.

Without the precedent of Watteau’s fêtes champêtres (festivals or garden parties) Manet might never have found his way to the conception of perhaps his sheerest, most intractable masterpiece…. Furthermore, the Déjeuner’s relation to Watteau’s art is not simply generic. When Manet’s painting was first exhibited at the Salon des Refusés in 1863 it was called Le Bain, a title which inevitably directs attention to the woman who has waded up to her knees in the stream or pond in the middle distance and who now raises her shift and bends over as if to fill some sort of cup or other receptacle with water. There is no equivalent for this figure in Marcantonio’s engraving.

But there is a painting by Watteau, La Villageoise, which also depicts a woman wading in shallow water while raising her skirt and turning her head to the side, and from which I believe Manet adapted the pose of the bathing woman in the Déjeuner…. Manet’s use of La Villageoise, especially in conjunction with the original title of the painting, is evidence for the suggestion that Watteau’s art presides over the conception of the Déjeuner as a whole.

But in another sense Manet did not break with that view so much as subsume it in a broader and more fecund vision of Frenchness. He did not, for example, give up seeing French painting as essentially committed to the values, including the ethical values, of realism. Nor did he repudiate his previous canon of French painters: on the contrary, his decision to make the first painting to embody his new vision of Frenchness a large fête galante, and moreover to base the one figure not accounted for by Marcantonio’s engraving on a painting by Watteau, specifically established the Déjeuner’s continuity with his previous work and with the view of the history of French painting on which that work rested. Finally, however, these paintings jointly represent a turning point in Manet’s career. In them, by a supreme feat of imagination, Manet discovered the reconcilability, even the deep affinity, between both the Florentine and the Venetian art of the High Renaissance and a conception of the natural genius of French painting that had been formulated largely in opposition to that art and which Manet himself, it seems, had previously held; and by so doing he achieved access, once and for all, to something like the entire range of the great painting of the past … an undertaking, a phase of Manet’s development to which he could never return.

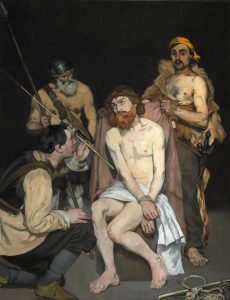

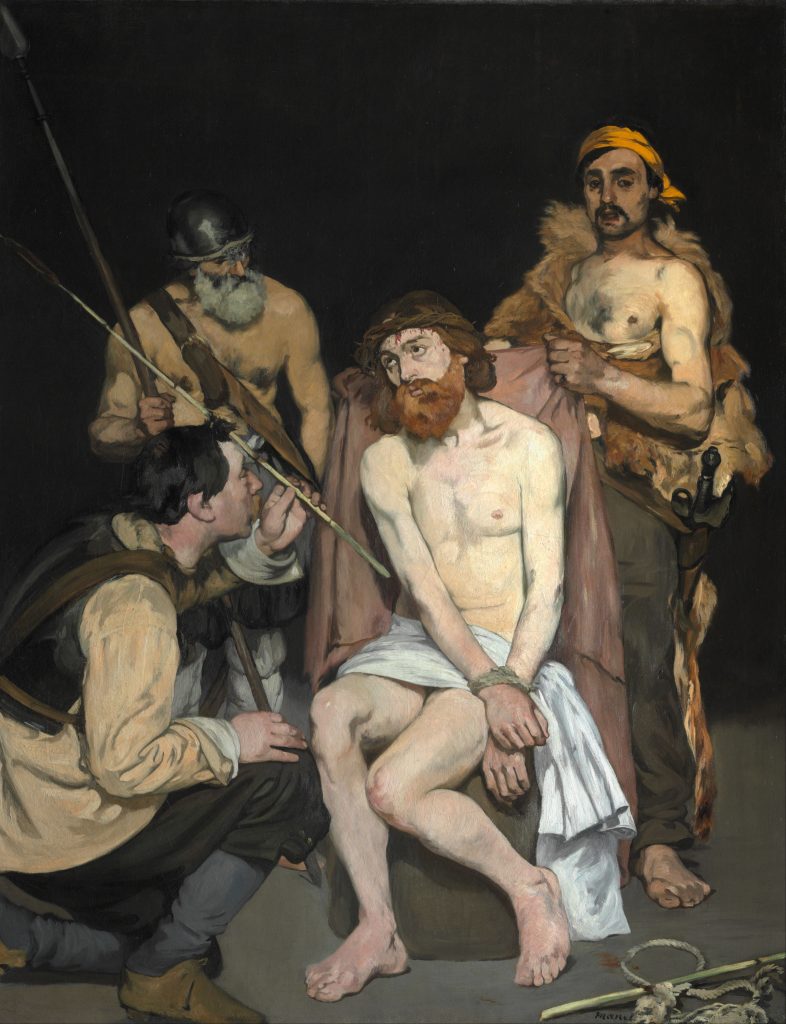

In 1865 Manet offended Parisian sensibilities once again with two monumental new paintings. Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers is a modernized interpretation of Christ’s last hours before his crucifixion. It offers a crude rendition of a sacred subject normally idealized and aggrandized in art. There is a possibility that Manet was inspired by the recently published biography Vie de Jésus (Life of Jesus) (1863), a controversial biography by Joseph-Ernest Renan which emphasized the humanity of Christ. Here, Manet portrays Jesus as a helpless human being at the mercy of the mercenaries who taunt him. His unpolished technique furthers the sense of the here and now and accentuates the representation of an unidealized Christ. By straying from the Gospel narrative by portraying the soldiers as ambivalent actors, Manet further modernizes the scene and sabotages the expected narrative.

2.4

| Olympia in Context

Manet’s second contribution to the exhibition that year, Olympia, stunned the Salon and set off a furor for its impropriety and its flagrant attack on conventional representations of the female nude. The public perceived the painting as shockingly decadent, not least of which for its marked sexuality.

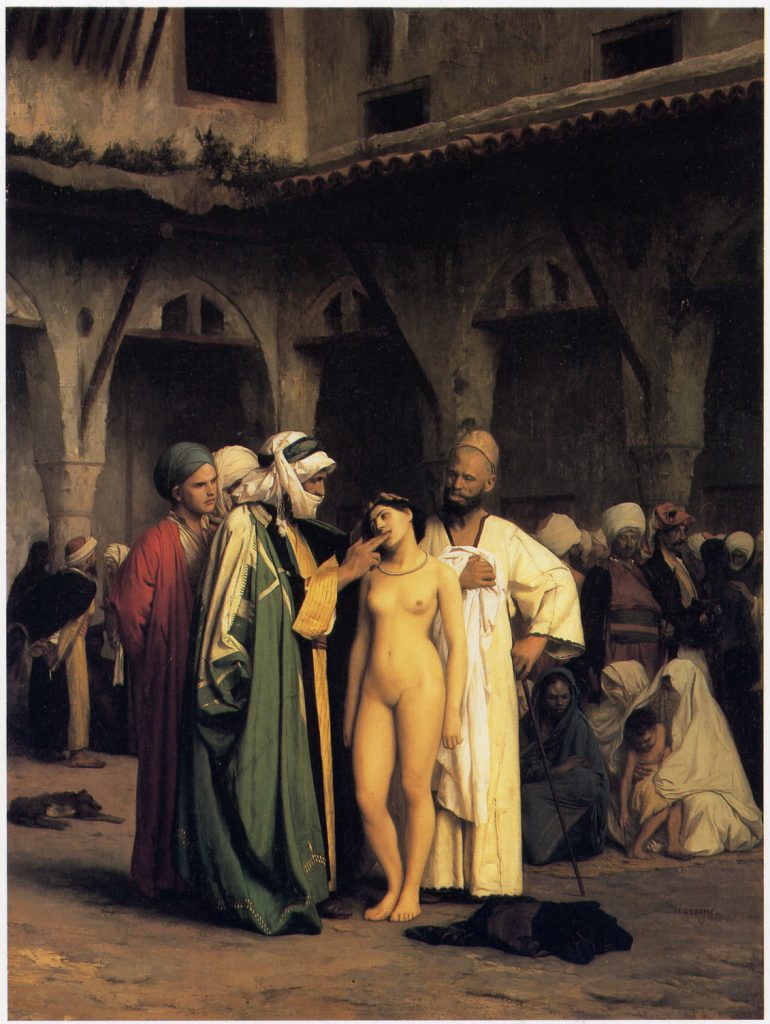

Manet’s Olympia may be seen as a subversion of a genre of Classicist Orientalism that favoured harems and odalisques and the fictionalized imagery of slave sex markets. Gerome’s Slave Market, painted around the same time as Olympia, is an example of this genre. The scene portrays prospective buyers examining an enslaved woman. Her eyes are shut, and she is depicted as passive and powerless. The image contrasts with Manet’s courtesan, who unabashedly articulates her autonomy and power as she gazes out at her clients/viewers. Her stare implicates the spectator extending the inference of the representation of her sexualized body.

As in Gerome’s work, however, the ideological opposition of blacks and whites formally articulated in the dynamics of the painted passages of light and dark intimates a fundamental aspect of the oppressed status of blacks in Western society: the relationship between black people and white people as articulated in the domestic role of the black maid. The black woman is cast as a caretaker, freeing the courtesan for her work, her status clearly beneath that of her mistress.

The dialectic of Manet’s black and white symbolism also points to the colonial enterprise of the Second Empire. She is West Indian (as identified by her headdress) and has come to Paris for work, pressed into the service of a high-class prostitute. The servant represents status, an asset to ‘Olympia,’ but also a sign of the taint of imperialism. The juxtaposition of the courtesan and the exoticized black servant points to a world-embracing political system.

Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby writes in “Still Thinking about Olympia’s Maid” (Art Bulletin 97, no. 4 (2015): 430–51):

Manet’s Olympia painted in 1863 and exhibited at the Salon of 1865, focuses on the modern, post-Revolutionary condition of white and black bodies, but it redefines them as female. Here, I turn back to this most famous nineteenth-century French painting in order to think further about the relationship between French workers and freed slaves in a picture that cites but modernizes the conventional iconography of the white female nude and a darker, some- times older, sometimes partly clothed subordinate attendant, whether in early modern paintings such as Titian’s Venus d’Urbino of 1538 or nineteenth-century Orientalist pictures.

Manet’s painting has often been discussed as the picture of one woman, the white woman who gives the painting its name. Cat, Negress, shawl, slippers: these are Olympia’s accessories….Whatever the origins of the model herself, the figure in Manet’s picture brought the colonies to the metropole. She heightened viewers’ awareness of racial difference and the colonial history of slavery, including art historical precedents, not only Orientalist paintings but also the many pictures of light-skinned Caribbean women accompanied by dark slaves).

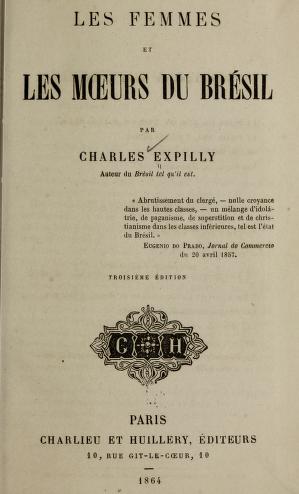

French images of slave societies in the Caribbean and Americas often juxtaposed supine white Creole women and their standing, some- times half-naked, black slaves, as can be seen in the title page illustration to Charles Expilly’s Les femmes et les moeurs du Brésil (The Women and Customs of Brazil) published in Paris the same year that Manet painted his picture.

In fact, the black model is Laure. Manet’s notebooks reveal that she lived at 11, Rue de Vintimille, a short walk from the artist’s studio in the 9th Arrondissement of Paris. Since the abolition of slavery in France in 1848, there was a growing black working class and many had settled in Manet’s neighbourhood. In his notebooks, Manet refers to Laure as a “very beautiful black woman.”

Manet shows her in contemporary French costume, in contrast to the exoticised harem attire common for black servants in salon paintings of the era. He also gives her almost equal pictorial space to Olympia. Manet’s decision to paint Laure fully clothed is what Denise Murrell terms “a fraught modernisation of the typical portrayal of black maids in places of sex work… He is showing her as a free, wage-earning woman in modern Paris,” but it “shows the limits of freedom in a society which is still essentially racist and sexist, those limits of freedom for both these women.”

Laure appears in three paintings by Manet; as the servant in Olympia, as a nanny in Children in the Tuileries Gardens and in a portrait painted around the same time as Olympia.

Titled initially La Négresse, “an art historical device that marginalized, actually obliterated the individual identities of women,” the painting has since been renamed Portrait of Laure due to Murrell’s research findings. It was initially thought to be a preparatory study for the servant in Olympia. Murrell argues that “the specific formal qualities of the painting suggest that he is rendering her as an individual…There is the sense of an expression, she’s not just a generic type.” (Denise M. Murrell, “Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet’s Olympia to Matisse, Bearden and Beyond,” Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 2014)

As for the black cat in Olympia, John F. Moffitt, in “Provocative Felinity in Manet’s Olympia” (Source: Notes in the History of Art 14, no. 1 (1994): 21–31), explores the meaning of the black cat. Rather than a lap dog, a typical symbol of marital fidelity, Manet “perversely substitutes an upright, aroused, and spitting black cat.”

The popular press often mentioned the offending black cat. Emile Zola, the well-known French novelist, journalist, and playwright, put it: ‘I also saw the Olympia again, the model of which has the serious fault of resembling many [fallen] women of your acquaintance…. There is also a cat there, one that has greatly diverted the public. It is true that this cat is very comical; isn’t it though? and, to have put such a cat into that painting, why, that painter [Manet] must have been insane. Imagine that! a cat—and a black cat at that!’

“Why,” Moffitt asks, is the black cat associated with a woman “known for her promiscuous sexuality. As it turns out in this case, the solution is exclusively linguistic.” To a Frenchman—now as well as in 1865—the basis of the salacious formula is/was embarrassingly obvious: according to a standard Dictionnaire de I ‘argot moderne (as published in 1980): ‘CHAT. Sexe de la femme.’ … in 1865, as today, the meaning of any aroused black cat was/is guaranteed (at least in France) to be universally perceived as being obscène…. According to a 1615 French translation of Piero Valeriano’s Hieroglyphica of 1556 (originally in Latin), since the mid-sixteenth century, the female cat has been read as a traditional enseigne of “female lasciviousness.”

The art historian Eunice Lipton has written about Manet’s Olympia in terms of its powerful representation of the female experience. Studying the work one day in 1970, she described how she “could not shake the feeling that there was an event unfolding in Olympia and that the naked woman was staring quite alarmingly out of the picture.” … I could not make her recede behind the abstract forms I knew…This was a woman who could say yes, or she could say no.” “the model surveyed the viewer, resisting centuries of admonition to ingratiate herself…Locked behind her gaze were thoughts, an ego manoeuvring…And that is why in the spring of 1865 (they) shook with rage in front of Olympia. She was unmanageable; they knew she had to be contained….These men only meant to persuade her, a single unwieldy woman, to comply. But the plot they hatched and the map their worries charted took them way off the road of Art Appreciation and Art History and deep into twentieth-century sexual struggle. Everything was done to silence her.”

Contemporaries of Manet understood this aspect of the sitter and the subject and were harsh in their criticism of the painting. When it was first shown at the Salon in 1865, critics condemned it as scandalous and described the sitter as vicious and strange, a “woman of the night; a sort of female gorilla, a grotesque…” Authorities took the unprecedented step of cordoning off the painting. Manet’s distress was such that he considered destroying the picture, despite its embodiment of Baudelaire’s advocacy for the “gait, glance, and gesture” of modern life.

The red-headed sitter with the unflinching gaze was a painter’s model by the name of Victorine Meurent, who posed for Manet nine times between 1862 and 1874, beginning with his first succès de scandale, Dejeuner sur l’herbe. That same year Manet posed Victorine as an Espada, a male matador.

The work is unusual in the power it assigns the female subject, albeit via her costumed portrayal as a man. Her blunt stare, and the iconic stillness of her pose arrest the viewers’ gaze as they halt the unfolding drama of the imaged bullring.

In her lifetime, her critics were many, their comments generally dismissive and often harsh.

1867, Emile Zola:

“Here in Olympia in the flesh is a girl whom the artist put on canvas in her youthful, slightly tarnished nakedness…He has introduced us to Olympia…whom we have met in the streets…”

1902, Theodore Duret:

“She was a young girl whom Manet met by chance in the middle of a crowd in a room at the Palais de Justice.”

1921, Tabarant:

“After having attempted without much success, to give music lessons, Victorine tried to paint. She asked for advice…from Etienne Leroy, an obscure painter…In 1876 she sent them her own portrait and then some historic or anecdotal paintings. Wretched little daubs.” Tabarant described her as a wreck by the age of 40, reduced to selling her drawings to her “companions of the night,” and that she had fallen into drunkenness and depravity and then outright disappeared.

Lipton’s contemporary view differs significantly: “I never saw her that way. Was I missing the point…I don’t think so? Manet had made her an interesting, compassionate, and even talented artist who does not ask, or need anything from the world of men… ” A feminist art historian, Lipton set out to reconstruct Meurent’s experience, in her image.

Meurent was an aspiring artist as well as a professional artist’s model. While the information uncovered to date is scant, her biography is quite different from that described by Tabarant. Meurent’s family was working-class, and she began modelling for Manet in 1862, possibly through a meeting at the studio of Thomas Couture, his former teacher. She is believed to have travelled to America in the early 1870s, perhaps engaged by an art dealer to accompany some paintings. However, she was back in Paris in 1875, attending evening classes at the Académie Julian, where she was instructed by the painter Etienne Leroy. Her self-portrait was shown at the Salon in 1876, the same year that Manet’s work was rejected.

Her paintings were then shown again in 1879, 1885 and 1904. In 1903 she was elected a member of the Société des artistes français.

As for her relationship with Manet, Lipton argues that it was unlikely that she was his grisette – a young woman in a casual relationship with an artist.

The quest for Victorine Meurent continued after Lipton. “Picture the predicament,” writes V.R. Main in his novel A Woman With No Clothes On (Delancey, 2008):

…she is 18, working-class, poor, with a secret ambition to become an artist. He is 30, rich, aristocratic, and a painter. The year is 1862; the setting, his studio in Paris. She is modelling for him, and, as they talk, their ideas merge. Two of the paintings he produces with her will become among the most famous in the world. But the majority of his biographers will ignore her influence. They will say that she was a prostitute and an alcoholic who died young. And, with that damning description, her contribution will be erased from art history.

The question remains: why was Meurent so dismissed by the painter’s biographers? After all, Manet’s inner circle seems to have recognised her importance. The artist’s close friend Antonin Proust noted in his memoirs that Meurent was Manet’s favourite model. Jacques-Emile Blanche, who also knew the painter, was moved to ask, ‘How often does a chance meeting between a painter and a model decisively influence the personality of his works?’

Certainly, Meurent’s willingness to pose naked made her a notorious figure to the general public, undermining her hopes of being taken seriously. As discussed earlier female nudes were highly appreciated in the 19th century as long as they remained anonymous representations of goddesses or mythical figures.

The controversy surrounding Manet’s Olympia was augmented by the fact that the painting was modelled on Titian’s Venus of Urbino and intended as a provocative counterpart. Olympia is Venus‘s antithesis in style and content, displaying a much closer affinity to Goya’s Naked Maja.

Manet’s friend Baudelaire had seen copies of Goya’s two Majas at a dealer’s gallery in 1859. Writing to the French photographer Nadar, he described them as pictures of “the Duchess of Alba … in one the Duchess wears Spanish dress, in the other, she is naked in the same pose flat on her back.”

Manet saw the two photographs. He painted and dedicated to Nadar a work entitled Young Woman in a Spanish Costume that has similarities to Clothed Maja.

Manet’s attraction to all things Spanish had many sources. Apart from the Galerie Espagnole at the Louvre, French collectors and museums assembled substantial holdings of works by Spanish masters as the nineteenth century unfolded, artists such as Velázquez and Goya who made a significant impact on modernist painting and aesthetic discourse. By the 1860s, the French taste for Spanish painting was perceptible at every Paris Salon. Manet finally visited Spain in 1865 and came to appreciate, and emulate Spanish painting of the Golden Age, an interest furthered by his access to reproductions of important works and spurred on by his friend Zacharie Astruc, a painter, poet, sculptor, and art critic, and a true Hispanophile.

While Salon-goers lined up to stare and scrutinize, they were unwilling, and likely unable, to confront the real issues inscribed in Olympia. An aggrieved Manet sought solace from Baudelaire in a letter in May 1865: “I wish you were here, my dear Baudelaire. The insults pour down like hailstones. It has never been quite this bad…I wish you were here to tell me what you think of my pictures. Your judgement is good, and the racket is quite annoying and it’s plain someone is wrong.”

Baudelaire, who had received his fair share of critical knocks, had little patience for his Manet’s distress, responding “People are making fun of you. The jokes are quite annoying. No one is doing you justice. And so on and so forth. Do you really believe you’re the first man who has ever been in such a position? Do you have more genius than Chateaubriand or Wagner? People mocked them. And it didn’t kill them.” (May 11, 1865)

On the heels of Manet’s scandalous Olympia, Courbet showed his equally provocative Woman with a Parrot the following year. The painting was censured by academics for its overt physicality and erotic symbolism but garnered praise from younger artists eager to thwart convention. That said, the idealization of the nude female body and her averted gaze rendered Courbet’s Woman with a Parrot less threatening to viewers than Olympia.

In addition, Woman with Parrot resembles the idealized conventional nudes of the era, such as The Birth of Venus by Alexandre Cabanel, which created a sensation at the Salon of 1863. For instance, the backward tip of the head and the complete self-absorption. But Cabanel’s Venus is an idealized image of a mythological subject; Courbet’s is a modern woman. Cabanel adheres to traditional modelling techniques and perfected soft brushwork that renders the work palatable. In contrast, Courbet’s Woman with a Parrot is overtly sexual, standing apart (for different reasons) from Manet’s Olympia or Cabanel’s Birth of Venus in its depiction of a slightly dangerous but implicitly compliant female.

While Courbet reached a high point in his popularity in 1866, the year was also disappointing. Rumours that he would receive the Legion of Honour Medal did not materialize, and a promised purchase reneged. Émilien de Nieuverkerke who was responsible for the organisation of the Paris Salon had visited Courbet’s studio in 1865 and agreed to buy Woman with a Parrot. The exchange of letters surrounding the event record the animosity at play. It became a turning point for Courbet, who was persona non grata from then on.

2.5

| The International Exposition of 1867

At the time of the International Exposition of 1867, a regulation was initiated that altered the jury composition. The members were reduced from 52 to 36 members, two-thirds of whom were elected by recognized artists among the exhibitors; the administration appointed the remaining jurors. This was a move to ensure that conservatism would prevail. Artists like Cabanel and Gerome headed the list of artists. The appointees from the administration included a roster of amateurs and museum curators, as well as the influential but conservative art critics Charles Blanc, Paul de Saint-Victor and Theophile Gautier.

This conservativism in French artistic policy was related to a concern with the nation’s international reputation. In 1866 the politician Marie Édouard Vaillant stated: “Representatives of the French school, remember that the entire art world has its eyes fixed on the works of this school and try to add jewels to its glorious crown.”

Because of the economics of the exposition, its audience and international clientele, artists felt a keen need to participate. At the same time, the administrators sought to present a small select showing of what they deemed the best artists of the nation. Artists such as Édouard Manet, Gustave Courbet, Alfred Sisley, Frédéric Bazille, Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir were rejected even after several petitions of appeal.

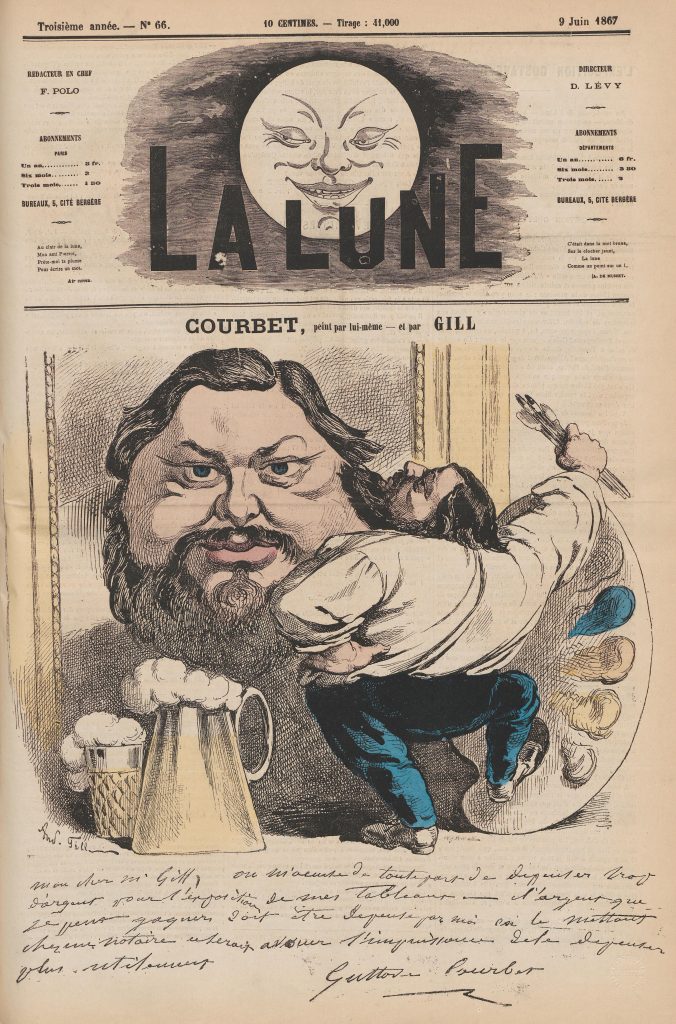

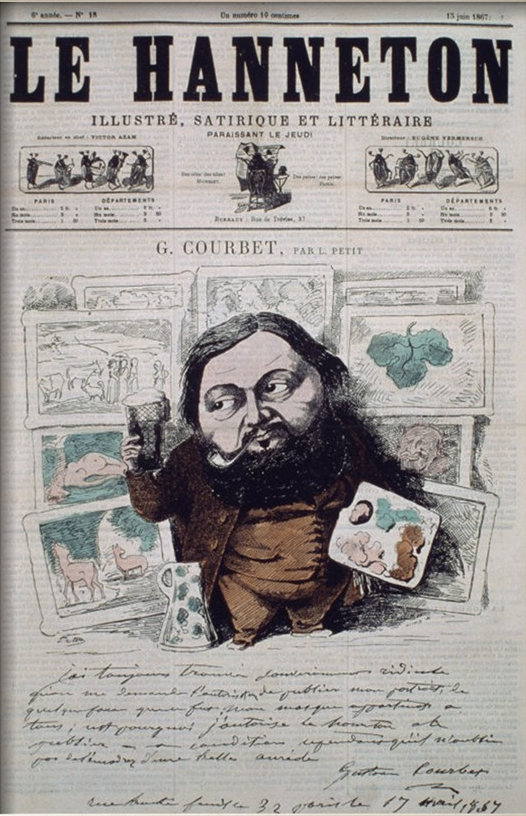

The most vigorous and visible protest was that of Courbet, who built his own pavilion close to the exhibition, as he had done in 1855 when he exhibited The Painter’s Studio. The jury in 1855 accepted eleven of Courbet’s works for the Exposition Universelle in Paris, but The Painter’s Studio was not among them. Undeterred, Courbet, with the help of Alfred Bruyas, opened his exhibition (The Pavilion of Realism) near the official exposition.

Courbet’s intention in 1867 was more grandiose. He intended to erect a permanent exhibition space that would provide an ongoing installation of his work. He wrote to Bruyas in 1867: “I am about to begin building, near the spot I used in 55. This time I will set up a definite atelier for the rest of my life and will send almost nothing to the exhibitions of the Government that has always treated me so badly.”

Courbet began his construction of his “personal Louvre” with a display of over a hundred of his paintings borrowed from museums and private collectors. Monet wrote in late May: “Courbet’s exhibition opens in eight days…Imagine if you will, that he has invited all the artists of Paris for the opening; he has sent three thousand invitations and at the same time, for each artist he has enclosed his catalogue.”

While Courbet was mocked for his increased ambition and an extravagant sense of self in caricatures of the late 1860s, which depicted him as overweight and excessive in his habits, his exhibition of 1867 was well staged and took on a quasi-official character. Hippolyte Babbou described Courbet’s gallery as “an immense hall of …vast proportions” which came close to being a “second exposition universelle.”

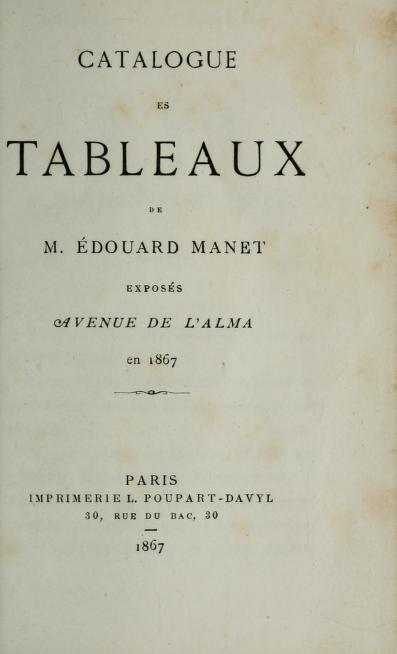

Like Courbet, Manet was undaunted by his rejection from the Exposition Universelle, determined to seize the opportunity offered by a world event to make his works known to a larger public. He was convinced that in doing so, he would gain the acceptance and appreciation he believed he merited. He borrowed 18,000 francs from his inheritance to construct a temporary wooden pavilion across the street from one of the entrances to the International Exposition, near the Pont de d’Alma, to hold an independent exhibition. It opened in May 1867, accompanied by a catalogue that spelled out the artist’s position. It was titled “Reasons for Holding a Private Exhibition” and stated:

The artist does not say to-day. ‘Come and see faultless work but come and see sincere work’. The sincerity gives the work a character of protest, albeit the painter merely thought of rendering his impression. Manet has never wished to protest. It is rather against him who did not expect it that people have protested because there is a traditional system of teaching form, technique, and appearances in painting, and because those who have been brought up according to such principles do not acknowledge any other. From this they derive their naive intolerance.

Manet’s exhibition pavilion was located on the right bank of the Seine, at the height of the Trocadéro. This vantage point afforded him a panoramic view of the Champ de Mars and the grounds of the Exposition. His unfinished painting is presented as a mise-en-scène, less a record of the World Fair than a pastiche of the event within the context of the modern metropolis. The compressed, layered foreground is an amalgam of scales and perspectives, a stage for the disparate groups dispersed across its shallow ground. Among the figures is young Leon Koella Leenhoff, Manet’s stepson, who is walking his dog, a trio of uniformed military men, a bourgeois couple (he with binoculars, she with a parasol), a group of female friends, a lady on horseback, and a gardener, the most prominent figure, diligently tending the grounds. In its diversity of age and class status, the painting presents a microcosm of Parisian society at a particular moment. The lack of spatial coherence: the old Paris blending with new architecture, and the middle-ground collapsing on itself, underscores the image’s narrative ambiguity and suggests the artist’s subtext.

According to Patricia Mainardi in Art and Politics of the Second Empire: the Universal Expositions of 1855 and 1867 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), 128), “in setting up his own exhibition and in painting his View of the Exposition Universelle, Manet sought to identify himself with the leading themes of the enterprise, optimism, universality and progress. While appearing to go along with the political views of the time, Manet’s View of the Exposition Universelle critiques not only the French government, but the fine arts display at the 1867 Exposition.”

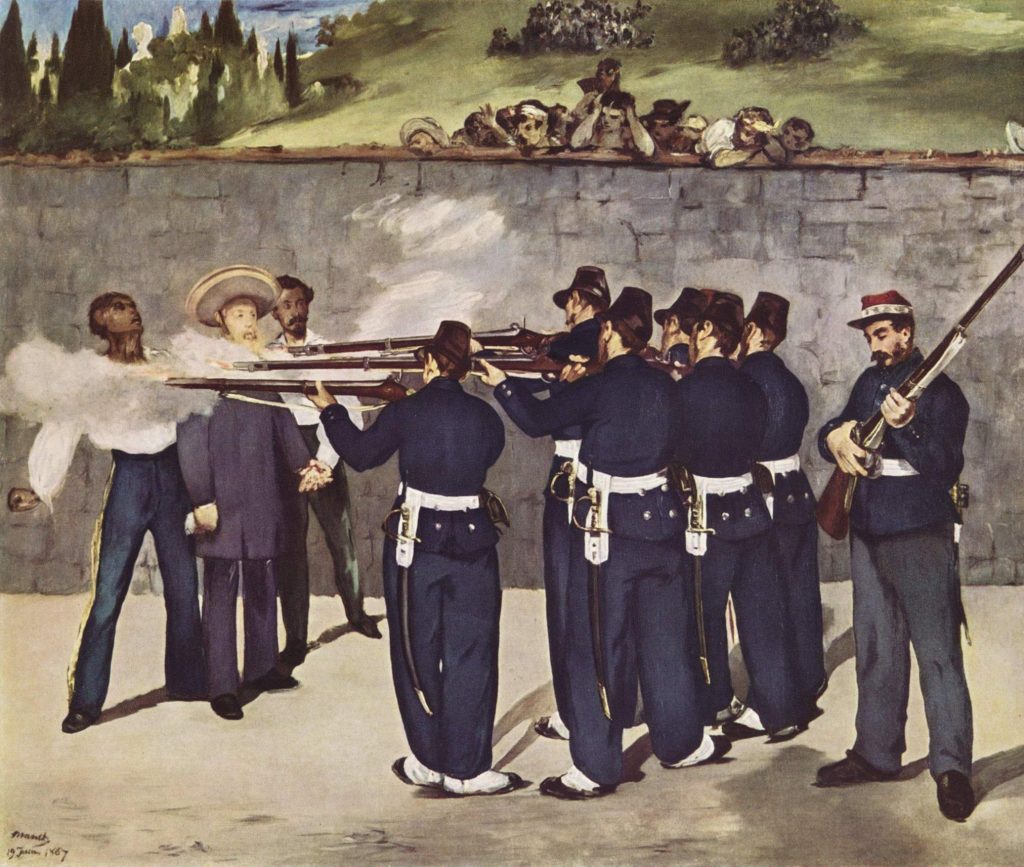

2.6

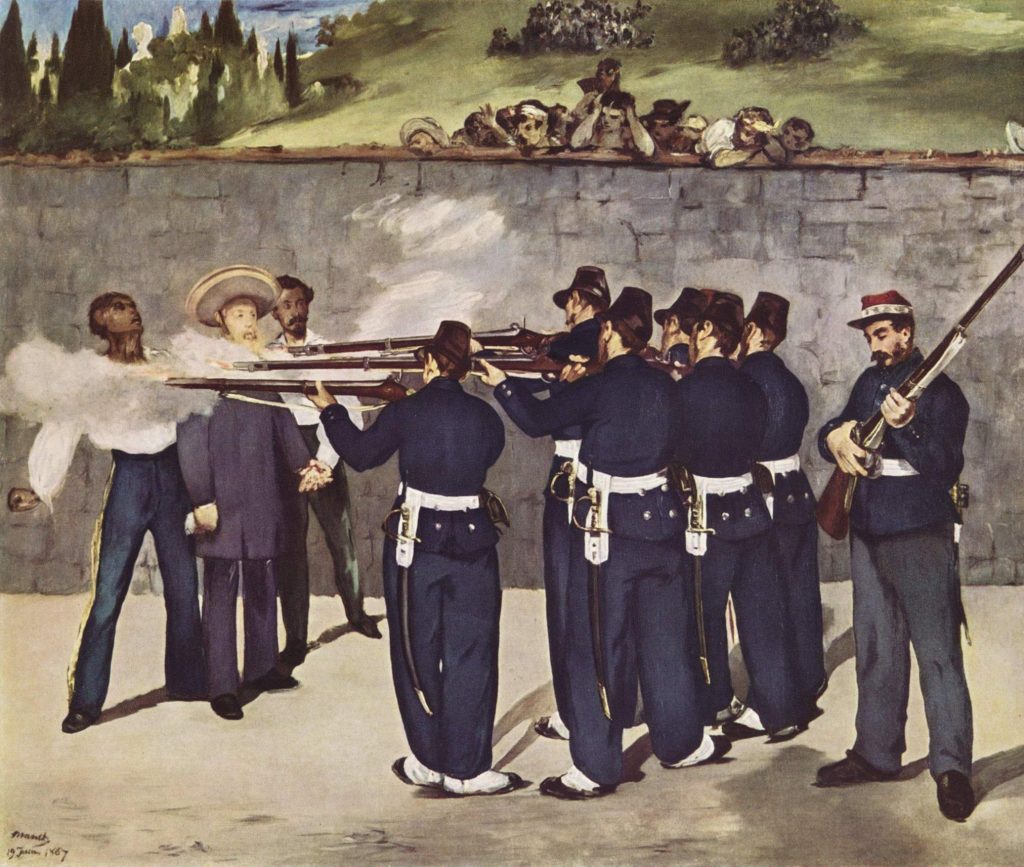

| The Political Manet: The Execution of Emperor Maximilian

Manet’s lifelong commitment to the Republic is well known. He disdained the Empire and its decorations, refusing the Legion of Honour in 1868, and dismissing the award as a “dirty gewgaw suitable for children and regime toadies.”

Philip Nord has argued the question of whether Manet was a radical republican in Manet and Radical Politics (Journal of Interdisciplinary History 19, no. 3 (Winter 1989): 447–480):

Manet’s republicanism is not in question, but was he, in fact a radical? Three kinds of evidence will be adduced to make the case. The artist was bound by ties of family and sociability to the radical republican camp. He produced a body of work resonant with themes congenial to radicals. And he placed himself in the forefront of a campaign to democratize the salon, a politicized campaign which paralleled in rhetoric and even in personnel contemporaneous efforts to found a democratic Republic.”

Manet frequented republican circles early on, fraternizing with party bigwigs at salons and cafes, Tortoni’s on the boulevard des Italiens and the radical Cafe Frontin. His social meeting places with fellow painters at the Cafe Guerbois in the 1860s and the Cafe de la Nouvelle-Athene in the 1870s included radically inclined art critics, of whom Emile Zola, Philippe Burty and Theodore Duret were the most ardent.

Nord asks, “Does such a pattern of sociability suggest Manet was also a radical? Manet’s oeuvre itself argues for such a conclusion. Over a twenty-year career, the artist exhibited a remarkable and persistent penchant for politically charged subjects and themes. The point will not be disputed in the case of Manet’s treatment of the execution of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico.”

The execution of the emperor Maximilian in Mexico occurred on June 19, 1867, during the Universal Exposition in Paris, and Manet’s exposition particulière on Place d’Alma. When word reached the capital on July 1, Manet reportedly abandoned the work underway on his Vue de l’exposition to paint this political event. Shortly after that he started the first of five versions of The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, a project that would occupy him until censors informed him that should he try to submit The Execution to the Salon of 1869, it would be rejected and that they would not allow his lithograph of the same subject to be printed.

Manet’s painting represents the moments before the execution of the Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph of Austria, the emperor of Mexico. Three years earlier, to establish an economic and political foothold in North America, Napoleon III of France had placed Maximilian on the throne of Mexico and supported him militarily. The United States refused to recognize Maximilian’s rule and supported Benito Juárez, the republican president. After the American Civil War, the United States pressured France to remove her troops, warning that their presence on North American soil violated the Monroe Doctrine. Napoleon III complied, and by mid-March 1867, French forces had departed Mexico. Maximilian, however, refused to remove himself to safety and was captured in Querétaro in May. The following month, with his Mexican generals Tomás Mejía and Miguel Miramón, he was executed by firing squad. News of Maximilian’s death reached Paris ten days later, and immediately the French court went into mourning. Still, their expressions of grief could not mask that Napoleon III had aided Maximilian’s assumption of power in Mexico and then abandoned him to hostile forces. The Mexico debacle rapidly came to be seen, inside and outside of France, as one of Napoleon III’s worst political blunders and a critical factor in the demise of his government.

To the majority of Mexicans, the death of Maximilian was a victory which had ended a long period of civil war. But in France, it was regarded as a national humiliation and a blow to the prestige of the French emperor. The harrowing accounts of the execution and Maximilian’s courage in the face of a firing squad extended the narrative of victimization and betrayal, casting Napoleon’s policies as ambitious and deceitful.

By early 1869 Manet had completed a series of four paintings and one lithograph of the subject. His emphasis on the grandeur of the figures in the paintings reinforces the idea that his subject was conceived as a Salon-style major history painting. The significant compositional changes between versions (the altered position of the three victims and the two officers, the soldiers’ uniforms as well as the setting of the event) were, to some extent, due to the gradual disclosure of new facts about the execution that were published in French and Belgian papers.

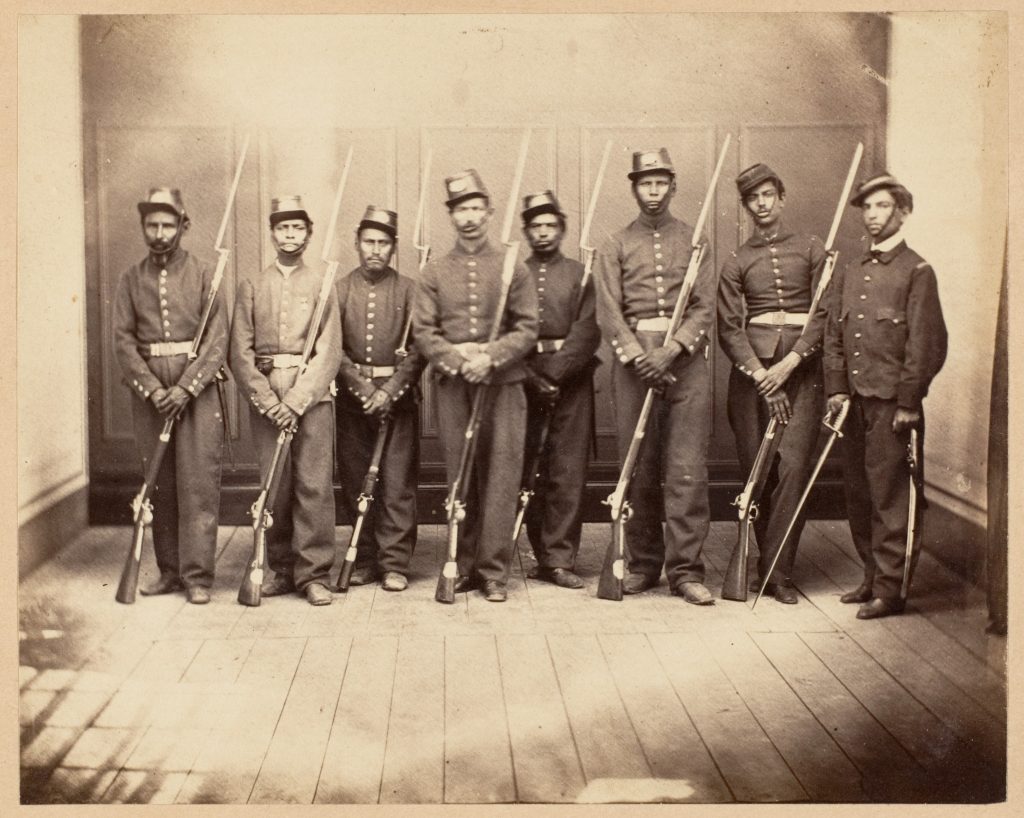

In the second version, the placement of Maximilian’s sombrero evokes the idea of a halo and, by extension, invokes a subtle suggestion of martyrdom. The grouping of the victims may also echo the image of Christ between thieves and calls to mind the French government’s false propaganda about Maximilian’s initial reception in Mexico as “a messiah awaited by the population.” But one of the more controversial aspects of the painting in this and subsequent versions is the presence of French troops in the firing squad, rather than soldiers of the Mexican Republic, as clearly seen in a photograph by François Aubert titled Emperor Maximilian’s Firing Squad.

In January 1869, Manet fell into conflict with French censors when he attempted to publish the lithograph. By law, all printed images had to be cleared by the government, and permission to publish was denied. The printer Alfred Lemercier refused to release the stone and demanded permission to have the image rubbed out. The incident soon became public when Zola came out strongly on Manet’s behalf:

- Eduard Manet has painted the tragic episode that ended our intervention in Mexico, the Death of Maximilian. It seems that this lamentable event has still not at all acquired the status of history because Manet was informed officially that this painting excellent in all other respects had every chance of not been admitted to the next Salon if he insisted on sending it. This is extraordinary and even more so is the fact that M. Eduard Manet had executed on a lithographic stone a sketch of the painted and when he delivered it to the printer Lemercier, an order was immediately given to prohibit the sale of this composition, even though it carried not title. ( see: Juliet Wilson-Bareau, ed., “Appendix II: Documents Relating to the ‘Maximilian Affair,” in Françoise Cachin, Charles S. Moffett, and Michel Melot, Manet 1832-1883 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1983), 531-32)

Manet’s Execution paintings were probably inspired by Goya’s The Third of May, 1808. The works followed his trip to Spain in the autumn of 1865 after seeing Goya’s paintings on display at the Prado. Manet would also have known Charles Yriarte’s monograph published in 1867, where the image was reproduced.

Many art historians have written about Manet’s Execution paintings. Kristine Ibsen in “Spectacle and Spectator in Édouard Manet’s Execution of Maximilian.” Oxford Art Journal 29, no. 2 (2006): 213, 215–226) offers a new perspective, arguing that the image connects with Manet’s biography:

Manet began his first version of the Execution during a period of extraordinary personal doubt. The unrelenting hostility to his work by both state authorities and art critics had led to a series of severe bouts of depression that sometimes incapacitated the artist completely, and the private exhibition that he had mounted at great expense a few months before had been ignored by the public. …the basic structure of the composition, with Maximilian in the centre and Mejía being shot, remains consistent throughout the series, and the prominence given to the firing squad, with a single executioner to the right, was present from the start.

As an artist whose access to the public was severely circumscribed by both informal and formal modes of state censorship, Manet would also have had a special investment in this negotiation of expression. As precarious as it is to conflate the personal with the political, it is difficult to approach the Execution series without taking into consideration the artist’s passionate involvement with a project he continued to develop for nearly two years, despite being informed that it would be rejected by the Salon, sight unseen. Thus, independently of the actual censorship of the Execution series, which would wait nearly forty years before public exhibition in France, Manet’s ongoing struggle with the repressive mechanisms of the Empire led to a project that is as much as aesthetic as political, and, in the end, personal as well.

Although it is fair to say that Manet was a man of bourgeois sensibilities, he was more than a mere provocateur. A committed Republican (and anti-Bonapartist), his politics leaned, if not toward revolution, clearly toward the radical left, and subversive political themes appear in several of his works.

As a nineteen-year-old art student, Manet had witnessed the barbarity of Louis Napoleon’s 1851 coup d’etat first-hand and was even briefly imprisoned. There is no need to exaggerate Manet’s stay in prison nor be surprised that his father, a prominent judge, was able to secure his prompt release. Suffice it to say that he was on the streets during the fighting and could not have failed to be affected when, a few days later, Thomas Couture took his young art students to Montmartre Cemetery to view the hundreds of bodies awaiting identification by family members.

Zola refers to the rejection of Manet’s paintings by the salon as ‘veritable murder – an official assassination’. This, and other statements by Zola to this effect, has led to speculation that Manet is insinuating himself as the target of the squad in the Execution. On some level this is certainly plausible, especially when considered alongside Manet’s personalised renderings of the Passion and Crucifixion in The Dead Christ and the Angels (1864) and Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers (1865).

Manet’s insistence upon positioning the archduke between Mejía and Miramon (ignoring news reports to the contrary) and the crosses visible above the wall further seem to support this reading.

2.7

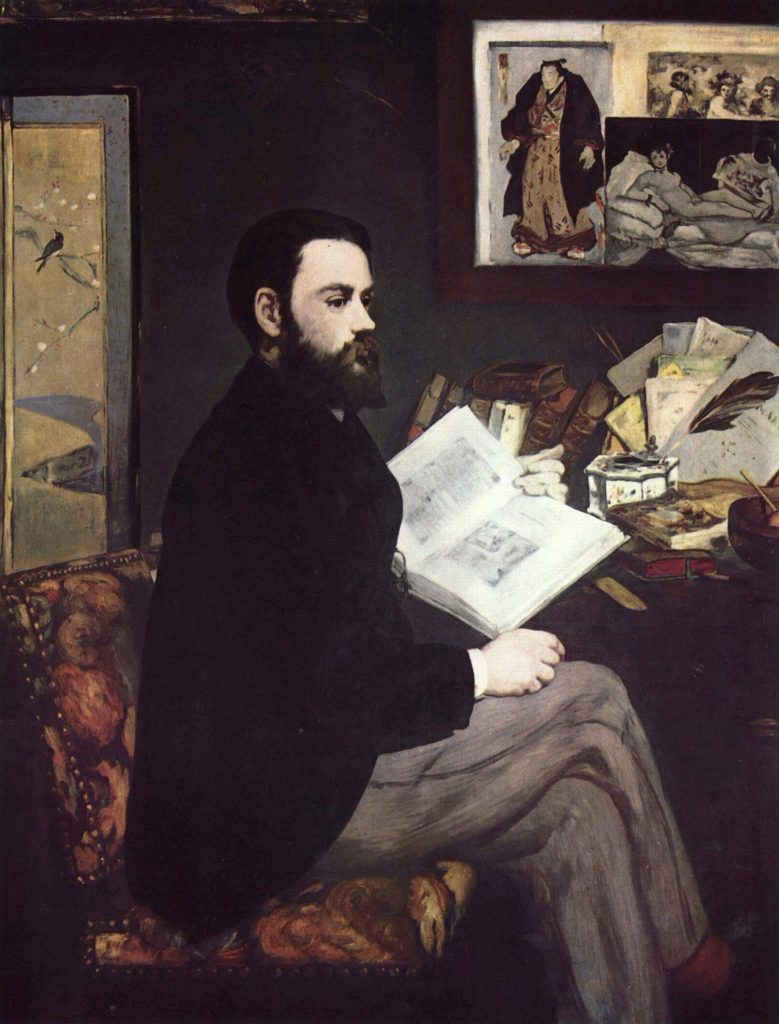

| Émile Zola, Japonisme and the Influence of the Orient

Émile Zola, a novelist and playwright and a significant figure in the political liberalization of France, was a champion of Manet’s work before they met. Zola’s first laudatory review of Manet appeared in the 1866 La Revue du XXe siècle. The following year he wrote a more detailed appreciation, later published by Dentu as a pseudo-publicity pamphlet for Manet’s private exhibition on the Place de l’Alma. It was entitled Une nouvelle manière en peinture. M. Édouard Manet (Edouard Manet, a Biographical and Critical Study) and was met with the usual critical derision save from Champfleury and Sainte-Beuve.

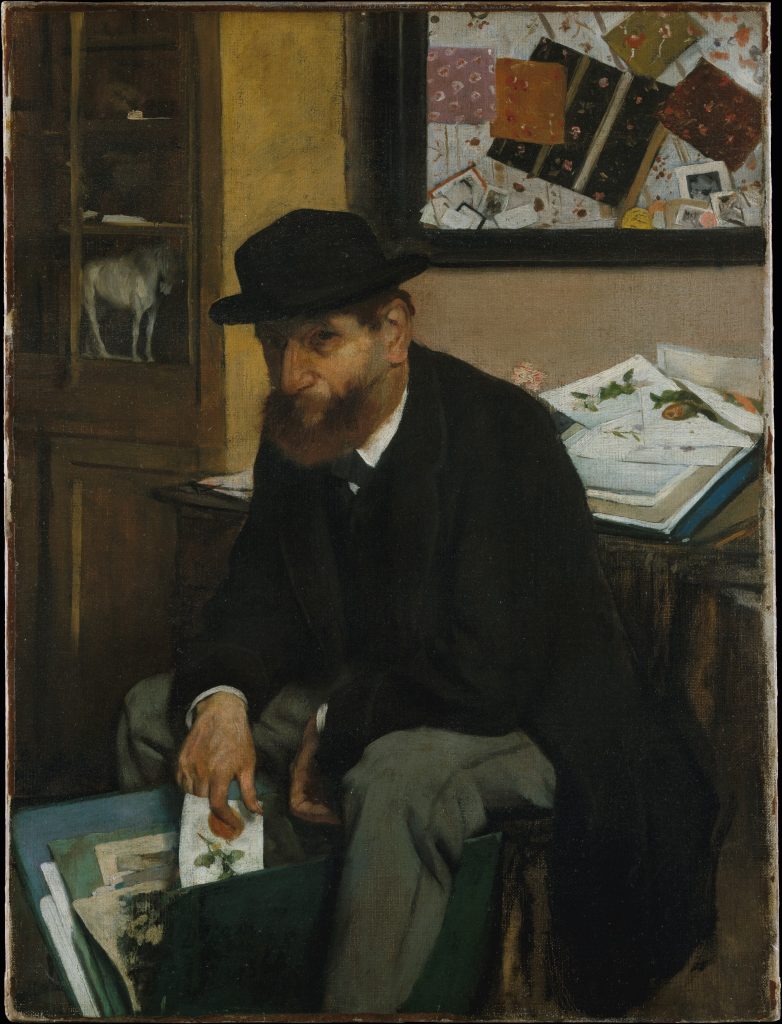

As a gesture of gratitude, Manet painted Zola’s portrait. The sittings occurred in February 1868 in Manet’s studio on the rue Guyot. The atelier was staged to reflect Zola’s personality and profession. He is depicted as a serious, cultured young man (twenty-seven at the time) seated at a desk covered with literary materials and utensils: an inkwell and quill, books, brochures and pamphlets. Among the seemingly haphazard clutter on the table, the bright blue brochure Une nouvelle manière en peinture. M. Édouard Manet, Revue du xixe siècle occupies pride of place.

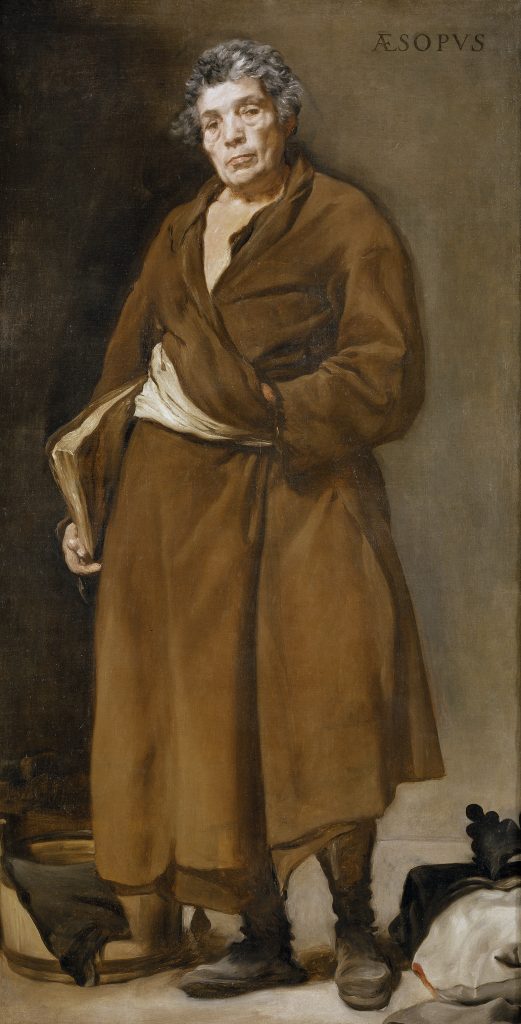

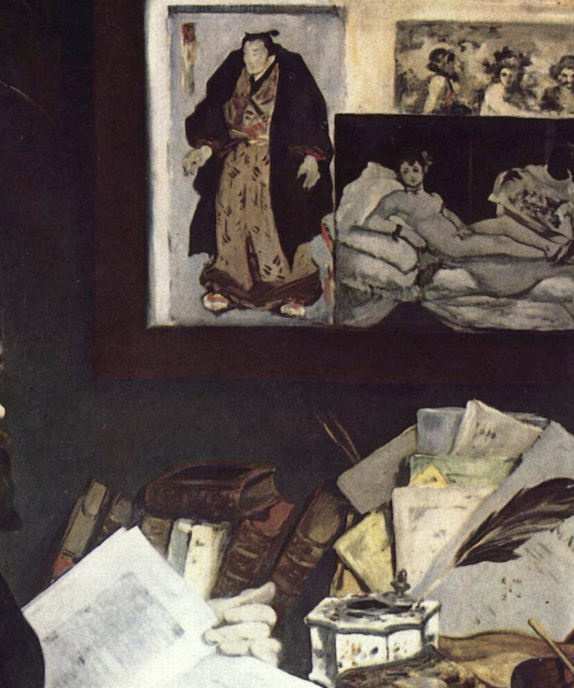

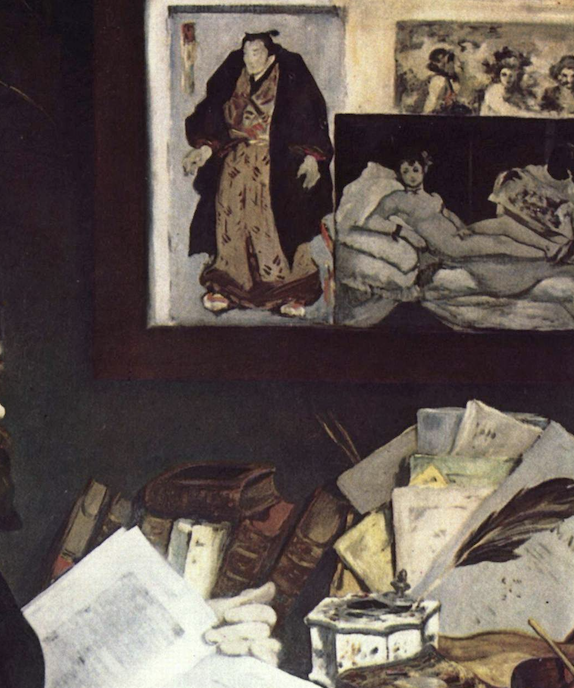

To underscore Zola’s art connoisseurship, Manet included a hanging display of timely visual reproductions behind the novelist’s desk. Among them is a black and white print of Olympia, a painting within a painting which visualizes the direct link between author and painter. Above Olympia a print hangs of Velazquez’s Bacchus to tell of the interest of both men in Spanish art. There is also a nineteenth-century Japanese print entitled The Wrestler by Utagawa Kunaki II, and behind Zola is a seventeenth-century Japanese screen in the manner of Ogata Korin. The presence of Japanese art in Manet’s portrait of Zola indicates the contemporary impact of the Far East on the Parisian avant-garde. This influence revolutionized artists’ conceptions of perspective and colour.

While ostensibly a portrait of Zola, the work is filled with details that refer to Manet himself and suggest recent controversies between the stale academicians at the Salon and the new directions being taken by progressive artists such as himself.

As Theodore Reff has noted in “Manet’s Portrait of Zola” (Burlington Magazine, 117 no. 862 (January 1975): 39):

The importance of objects surrounding Zola, attributes supposedly informing one about Zola, encourages the belief that they are expressions of Manet’s interests as an artist rather than Zola’s. The artist Odilon Redon observed in his Salon review (La Gironde, 9 June 1868), “It is rather a still life, so to speak, than the expression of a human being.” Zola himself was not entirely delighted with his portrait, which Manet presented to him; Charles-Marie-Georges Huysmans, the French novelist and art critic, noticed that he had relegated the painting to an antechamber of his home.

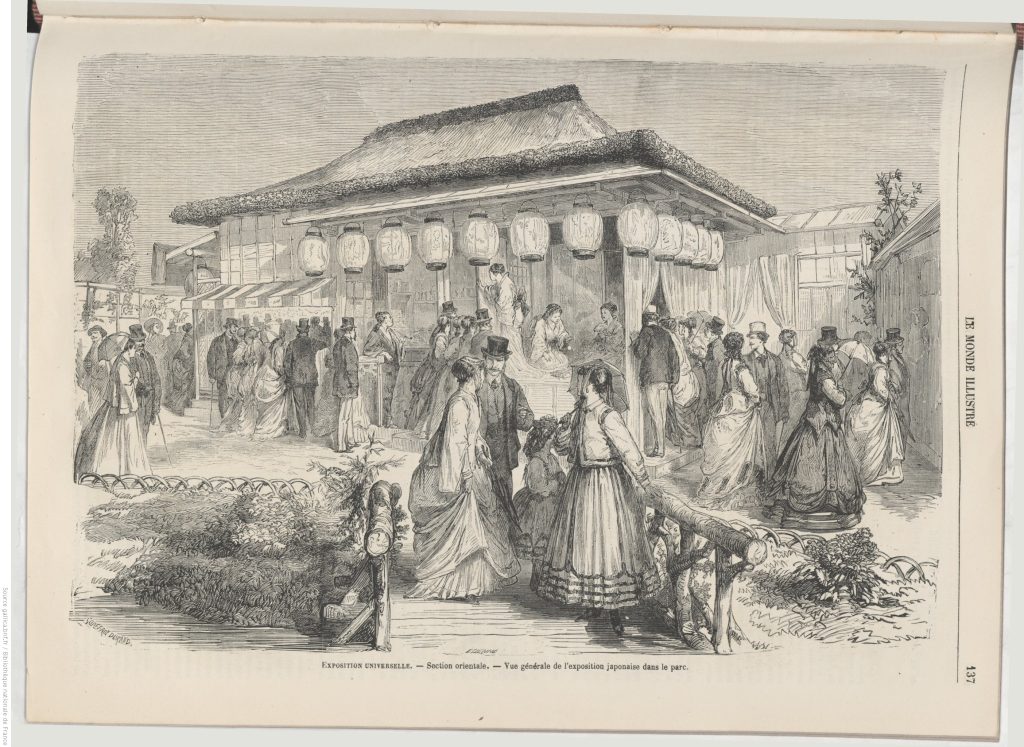

Japanese printmaking was the first non-Western art to impact European artists. Japanese ports reopened to trade with the West in 1853, leading to a tidal wave of importations into France. Parisians saw their first formal exhibition of Japanese arts and crafts in 1867. As a part of the Meiji government’s cultural exchange policy, a large display of traditional Japanese arts was held at the Exposition Universelle. It elicited widespread critical attention and praise. Parisian artists in Manet’s forward-thinking social orbit rapidly reacted to the new techniques and stylistic approaches; many began by collecting Japanese paintings and woodblocks.

Within less than a year, Manet was introducing Japanese stylistic elements into his works, as evidenced in the flat, cropped composition, bright colours, and unusual perspective of Portrait of Zola.

The influence of prints on Manet’s art, as evidenced in the portrait of Zola, has been elucidated by Anne Higonnet in “Manet and the Multiple” (Grey Room, no. 48 (2012): 102–16):

The history of art Manet began to cite in the 1860s was a history of art constituted not only by the original objects of that history but by the reproductions that translated those original objects into equally but differently visual form. What was foundationally modern about Manet in the 1860s was precisely that his citations were not only of what was original about the history of art but also about how the history of art had been profoundly transformed by reproductions of original art objects. Manet spent little time looking at the actual works of art he was supposedly so deeply affected by. He made one short trip to Spain in 1865 and another equally rapid trip to Flanders in 1872, whereas he spent most of the rest of his life absorbing the visual world of Paris. Paris was the capital of nineteenth-century reproduction as well as of museums, a world teeming with copies, prints, and photographs of all kinds.

Manet and his generation grew up with mass-reproduced images of the art of the past through the rapid advance of the semi-print, semi-photographic techniques that both overlapped and replaced one another and innovations in lithography and engraving. By the late 1860s, the Woodbury-type process, carbon intaglio, and photogravure were gaining popularity. Prints, however, remained the dominant mode of reproduction during Manet’s career, especially when they linked together text and image.

The Gazette des beaux-arts, the first French history periodical, announced a dual visual and textual history of art in its first issue in 1859 and went on to systematically publish prints after the masterpieces of the past, illustrating articles that organized art by artist, by national school, and according to chronology. Eventually, the contents of the magazine were gathered and published as a series of individual books under the heading Histoire des peintres.

Higonnet continues:

Manet’s Portrait of Zola was the product of this culture of visual reproduction. Like Edgar Degas, Manet had perceived a crucial shift in image technologies and his representation of Zola reprises a painting made by Edgar Degas in 1866 titled The Collector of Prints (L’amateur d’estampes). In both paintings, a male figure in black attire is seated in an interior filled with images within images organized in the upper right of the canvas, with a sliver of space devoted to elements that refer to art. Both figures hold printed matter in their hands. In Degas’s painting, the analogue to Manet’s Japanese screen is a cabinet containing a horse statuette—could it be a Japanese or Chinese statuette? In advance of Manet, Degas brought together the latest fashionable images of the East with the latest fashionable images of the West. Printed Japanese papers or fabric swatches are juxtaposed with photographs, among them carte de visite photographs, identifiable by their characteristic upright rectangular format and white borders. Degas contrasts new image technologies with old, the mass-reproduced pictures seen at the top, contrast with the traditional prints of flowers in the folio held by the collector. Manet, for his part, had raised the stakes by invoking Old Master paintings in the representation of the human figure.

…

During the decade before The Collector of Prints and the portrait of Zola, photography was reaching a new technical ability to reproduce other types of two-dimensional works of art. A spate of essays by eminent critics, such as Charles Blanc, published in prestigious periodicals, such as the Gazette des beaux-arts, debated this historic turn in terms of the relationship between painting, engraving, lithography, and photography. The issue was partly about an exponential increase in the potential audience for art. Less obvious, but more pertinent to artists such as Degas or Manet, who were imagining paintings like The Collector of Prints or the portrait of Zola, is that the issue was also about how well, and how differently, old and new image technologies could reproduce paintings.

2.8

| Édouard Manet’s Entourage

An examination of a series of atelier paintings by the artists in Manet’s circle, the group that Michael Fried dubbed the generation of 1863, makes an excellent introduction to the topos of the studio atelier as a means of presenting the artists’ collective and individual identities to the public.

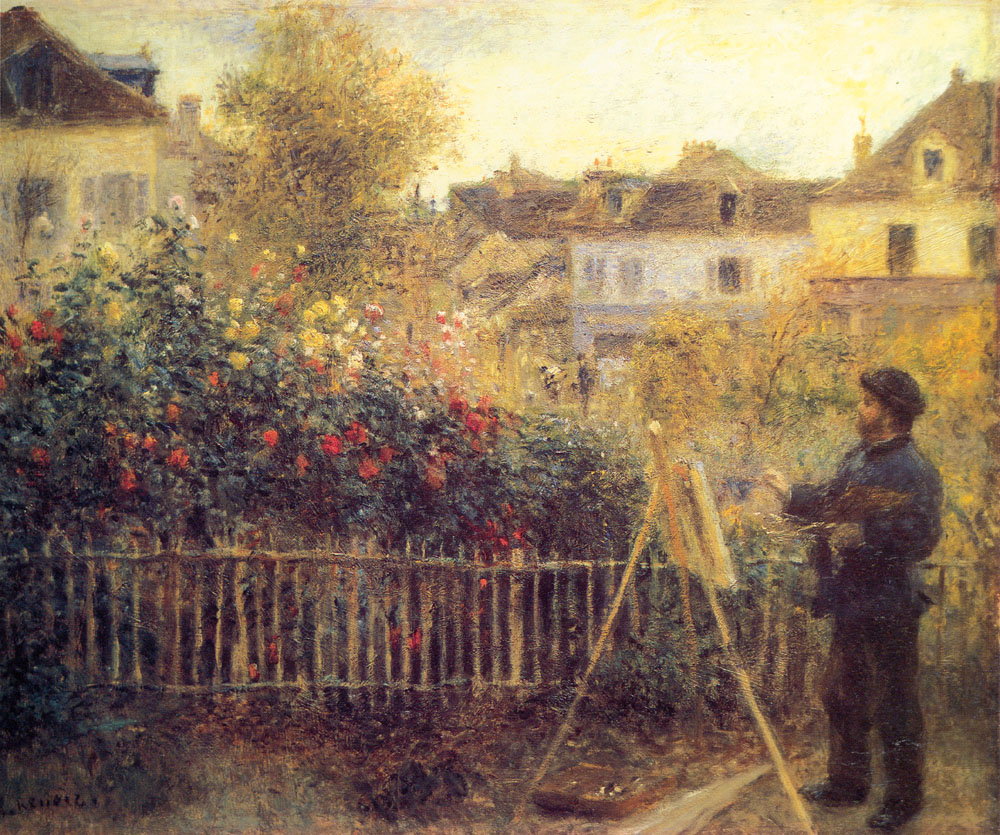

Bazille’s Studio is a case in point. Bazille was from a wine-growing family in Montpellier. His father was an elected Senator who chose to sit with Jules Ferry’s Gauche républicaine, and his family hoped he would make a career as a doctor and sent him to medical school in Paris in 1862. But he also enrolled as a student in the studio of the painter Charles Gleyre, where he came into contact with Alfred Sisley, Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir.

Bazille’s depiction of his studio at 9 rue de la Condamine, which he shared with Renoir from January 1868 to May 1870, is a scene that evokes the studio as a place of friendship and work. As he said in a letter home, “I have amused myself hitherto by painting the interior of my studio with my friends. Manet is painting me.” In work, Manet, Monet, and Bazille are looking at one of Bazille’s paintings. To the left, engaged in a separate conversation, are Renoir and Zola. Edmond Maître, an amateur musician and art collector, plays the piano in the right corner. On the wall are Bazille’s paintings, the Fisherman with a Net (1869-70) and The Toilette (1869), rejected by the Paris Salon, and Renoir’s Landscape with Two People, which had been shown at the 1866 Salon, indicators of the process of making, and showing art.

Compared to Bazille’s Studio, Fantin-Latour’s A Studio at Les Batignolles offers a formal view of a studio gathering of fellow artists. Batignolles was in the 17th arrondissement of Paris, where Édouard Manet and many of his circle lived and worked. Here, Fantin-Latour pays homage to his friend Manet whose centrality suggests his status as the leader of the informal group.

Manet is positioned at his easel as he paints the portrait of the artist and art critic Zacharie Astruc. The artists surrounding them include the German painter Otto Schölderer and, next to him, wearing a hat, Auguste Renoir. Further to the right, in the background, are the novelist Zola and the writer Edmond Maître, who were both art critics as well. Almost hidden in the corner is Claude Monet. Bazille, wearing tartan trousers, stands behind Manet’s chair.

The social dimension of the painters’ network continued less formally in the evenings. Needing a replacement for the interaction of the academy studios, they turned to the emerging cafe culture in Paris. They would meet up at the Cafe Guerbois, located centrally on the rue des Batignolles on Sunday nights and Thursday evenings, where conversations often became heated. These get-togethers played an essential role in the formative discussions around modern art, progressing from the obstacles imposed by the conservative Académie des Beaux-Arts to more engrossing exchanges on the way forward for new art forms.

The young Batignolles artists who orbited around Manet in the sixties would become the informal group known as the Impressionists a decade later. The group included Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Jean-Théodore Fantin-Latour, and Alfred Sisley. They were often joined by the patron and critic Maître, Zola and the photographer Nadar.

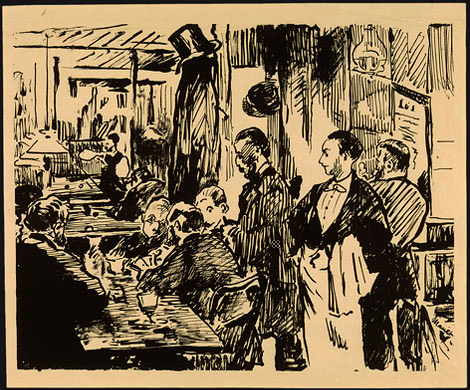

Manet’s At the Café captures the collegial atmosphere of the meeting place. Experimenting with transfer lithography, the artist used specially treated paper to create the original image, which was then transferred onto the surface of a prepared lithographic stone to be printed. The print suggests the quick, sketchy lines of a drawing as if the image had been produced on the spot, quickly and spontaneously.

2.9

| The Paris Commune, 1871

The execution of Maximilian dealt an irreparable blow to French power and prestige. In the summer of 1870, the fear of a Hohenzollern succession to the throne of Spain precipitated a crisis, and France declared war on Prussia on July 19. In August, the Prussian army advanced into Alsace and Lorraine, defeating the French and occupying the territories.

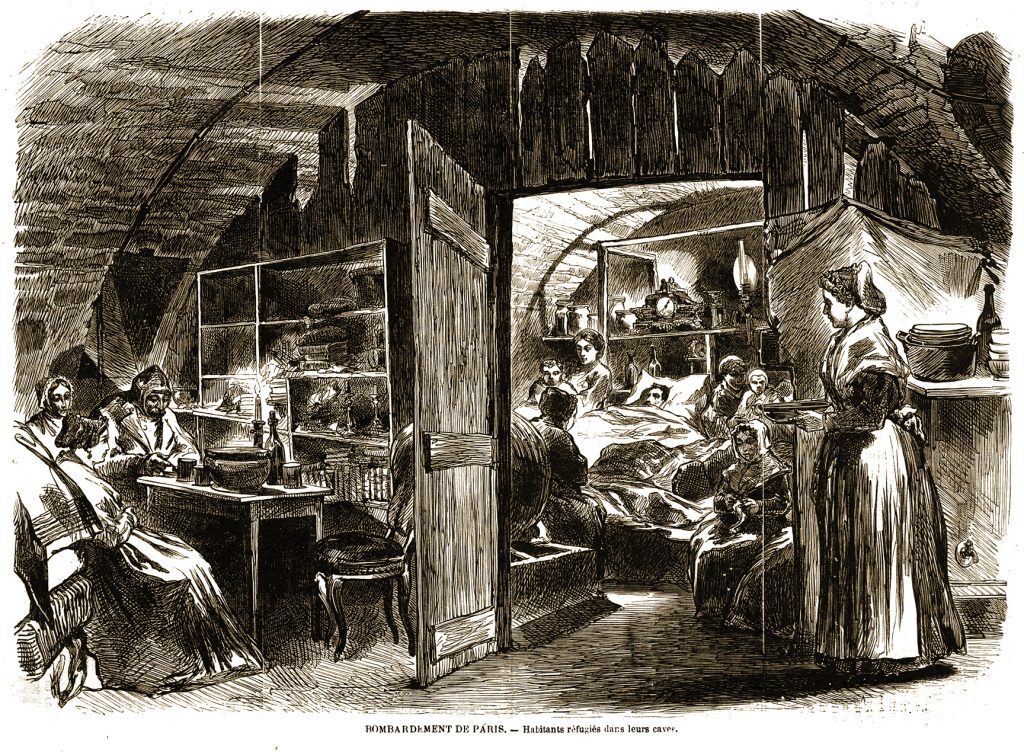

France’s crushing defeat in the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War, the capture of Napoleon and the siege of Paris by the Prussian army in September 1870 triggered the Paris insurrection. 1.7 million Parisians spent 135 days under siege, troops battled in the streets, and civilians took refuge in basements or makeshift shelters inside city monuments. The general populace was increasingly starved of life’s necessities. By January 1871, Paris surrendered in defeat. The same month, the French government signed the Armistice of Versailles with Otto von Bismarck, the Prussian leader and soon-to-be chancellor of a united Germany, who agreed to withdraw the troops from the French capital.

When France’s Third Republic was established in September 1870, it became clear that its parliament would comprise a conservative majority, sowing widespread fear of another monarchical form of government. Parisians felt obligated to rally for liberty, encouraged by activists of various credos, utopian socialists, and working-class leaders.

The Paris Commune began as an insurrection on March 18, 1871, when the largely left-wing, radical National Guard refused to accept the authority of the French government, seizing the power of the capital for two months during which it established policies that tended toward a progressive, secular system of social democracy.

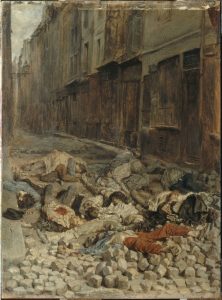

This print by Manet is set during the street fighting of the Paris Commune. The troops mirror the firing squad in his Execution of Maximilian. Here, instead of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, Manet depicts insurgent Parisian Communards executed by the French army.

During the Commune, fighting in the barricades was far more vicious and intense than the country had previously experienced. During the Commune’s final days, the notorious la semaine sanglante (“The Bloody Week”) an estimated 25,000 to 30,000 people were killed. Communards, innocent victims, and many more were arrested, and any man wearing a National Guard uniform was shot. One of the most brutal events was the lining up and killing of Communards against a wall in Pere Lachaise cemetery. By the time the fighting ended on May 28, corpses had filled the streets, and some forty thousand people had been arrested. Damage to properties was vast, and scarred, charred buildings again disfigured the city.

The sight of the brilliant metropolis in ruins was experienced as a defeat in itself. “A silence of death reigned over these ruins,” wrote Theophile Gautier in 1871 “…no clutter of vehicles, no shouts of children, not even the song of a bird…An incredible sadness invaded our souls.”

The response to the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune varied among modernist artists. Claude Monet, who had married Camille Doncieux in June and settled in London after the war broke out, was seemingly removed from the turmoil. Paul Cezanne remained in the south of France during the war. In the summer of 1870, the only artists directly involved were Auguste Renoir, who was drafted in August but was soon immobilized with dysentery, and the 28-year-old Frederic Bazille, who enlisted in the French military at the outset of the war and died in combat in November 1870. While Camille Pissarro was compelled to defend the new republic despite his Danish citizenship, the death of his infant daughter left him devastated. Berthe Morisot remained on the outskirts of Paris during the months of the siege and lived “a terrible nightmare” of fear and anxiety; the effects of the war were so severe that her health remained fragile for the rest of her life. After the Empire’s fall, Degas and Manet joined the military, enlisting in the National Guard.

Courbet, a self-declared pacifist, devoted himself to the protection of the national art collection as Paris prepared for a Prussian invasion, helping to establish the Commission artistique pour la sauvegarde des musées nationaux, the body responsible for the protection of cultural patrimony at the Louvre. He was elected its president in 1871. The position suited him ideally, as he explained in a letter to his father, “The Parisian artists as well as minister Jules Simon have just done me the honour of designating me president of the arts in the capital. This pleases me because I did not know how to serve my country in this emergency, having no inclination to bear arms.” In his inaugural address, he stated:

The artists of Paris who support the principles of the Communal Republic form themselves into a federation. This association of the creative minds of the city will be based on the following ideas: The free development of art without government protection or special privileges. Equal rights for all member of the Federation… The realm of the arts will be controlled by the artists who will have the following duties: To conserve the heritage of the party: To facilitate the creation and exhibition of contemporary works; To stimulate future creation through art education. (Federation of Artists of the Paris Commune 1871: Manifesto of the Paris Commune’s Federation of Artists, https://www.marxists.org/history/france/paris-commune/documents/artists.htm)

On April 7, Courbet recommended the abolition of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and the Academy and a complete revision of Salon regulations. Three days later, he was authorized by the Commune Council to convene a general assembly of artists and begin implementing a reform program. On April 27, he officially became part of the Commune’s government.

In a public statement, Courbet proposed that the Vendome Column be unbolted and that the sections be moved to the Hotel de la Monnaie. He phrased his arguments in aesthetic and political terms contending that “the column had no artistic merit” and epitomized “ideas of war and conquest” that were repellent to a republican action.” Courbet played on the country’s fears about the imminent siege, suggesting that when the Prussian army entered Paris, it would destroy the monument. After the Commune fell, Courbet was arrested as a participant, although he was convicted of the minor charge of “complicity in destroying the monument.” Zola stated, “If one weighed the scales of justice the crime of Courbet one would find there an ounce of anger against M. de Nieuwerkerke, an ounce of political lunacy, fifty kilograms of artistic infatuation and fifty kilograms of vanity.” Courbet was sentenced to six months in prison and a fine of 500 francs, a lenient sentence in comparison to that of the 16 Communards tried with him who were seriously penalized: one was deported from France, seven were sentenced to maximum security penal colonies, and two were condemned to death.

Courbet was thereafter no longer included in the Salon, his paintings refused on political grounds.

2.9

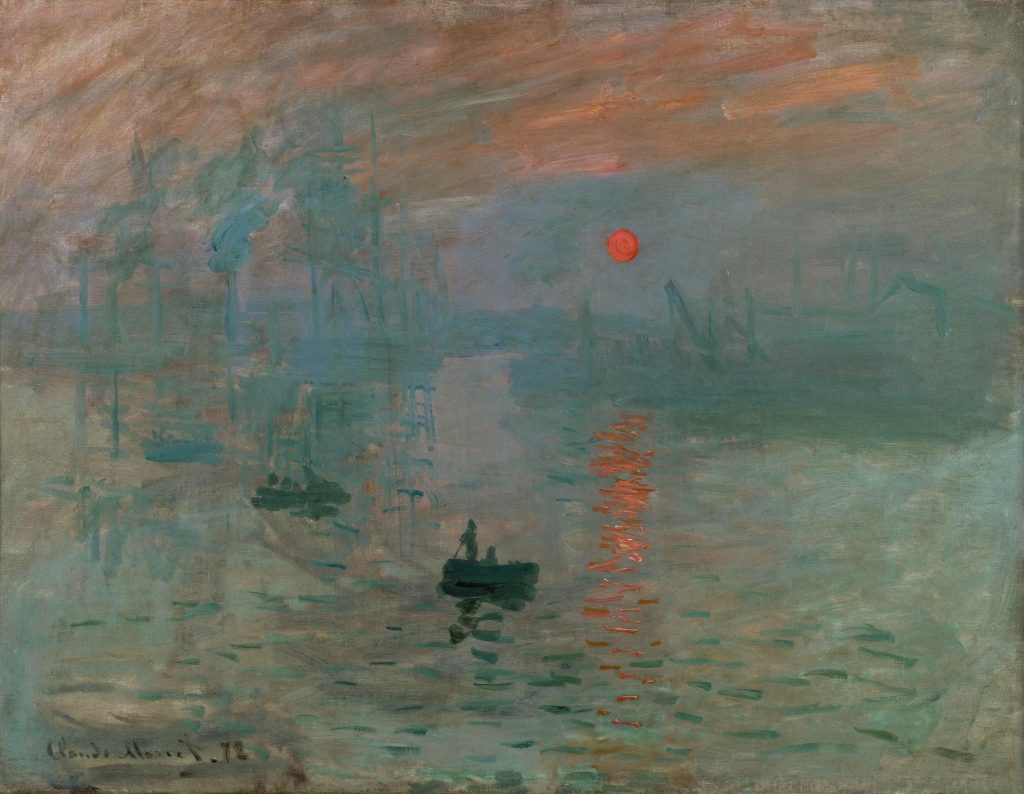

| Impressionism and its Contexts