Chapter Four

BERTHE MORISOT,

MARY CASSATT &

The Affluent Woman’s World

CONTENTS

Introduction

BERTHE MORISOT

4.1

4.2

4.3

4.4

4.5

4.6

4.7

4.8

4.9

MARY CASSATT

4.10

4.11

4.12

4.13

4.14

4.15

4.16

4.17

4.18

INTRODUCTION

.

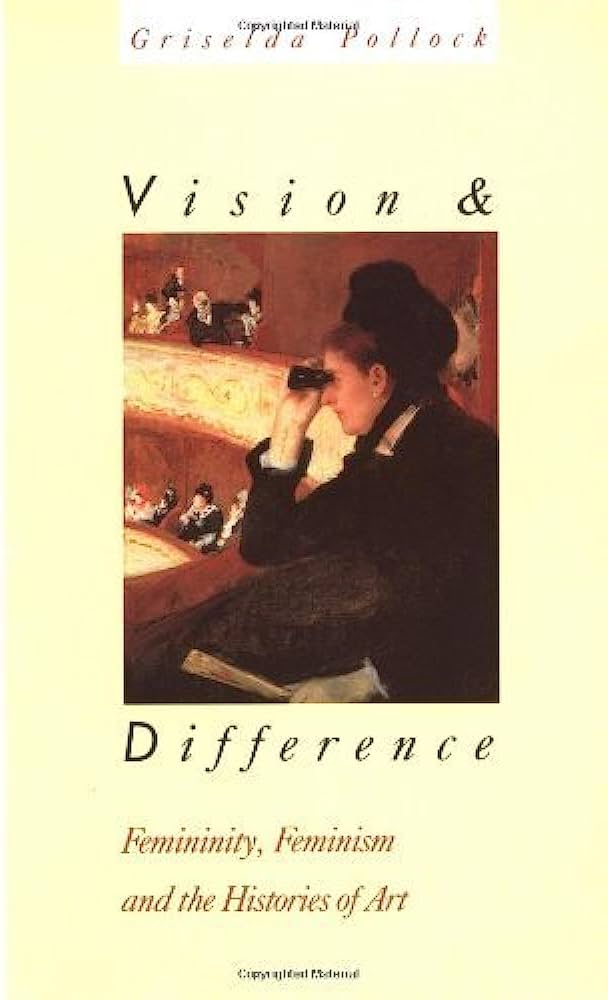

As Griselda Pollock has asserted in “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity” (Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art, 50-51), it is only through a consideration of the historical asymmetry between the social and economic realities of men and women in late nineteenth century Paris, that the relationship between sexuality, modernity and modernism can be understood. “This difference—the product of the social structuration of sexual difference and not any imaginary biological distinction—determined both what and how men and women painted.” Pollock further asserts that it is through the matrix of space that the socially contrived orders of sexual difference may ideally be analyzed. She writes, “Space can be grasped in several dimensions. The first refers us to spaces as locations. What spaces are represented in the paintings made by Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt? And what are not? The majority of these have to be recognized as examples of private areas or domestic space.”

Morisot and Cassatt painted mainly domestic interiors, but their images of public places and recreational venues such as the theatre, the park promenade, and the boating party, may be equally regarded as private spaces of the bourgeoisie. The radically evolving urban world of cafés, bars, and brothels, which provided their male counterparts with more modern subjects, remained off-limits. Yet despite their more narrow repertoire of subjects, Morisot and Cassatt fully exploited the domestic imagery available to them, creating complex works that often reflected their struggle with the shifting identities experienced by women as female artists entering the public, professional realm.

BERTHE MORISOT

4.1

| Public Debut

Berthe Morisot was born in Bourges to an upper-middle-class family. Her father, Edmé Tiburce Morisot, was a court official and her mother, Marie-Joséphine-Cornélie Thomas, was the great-niece of the Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard. In 1852, the family moved to Paris, to the area of Passy where Morisot would spend most of her life. As bourgeois young girls, it was de rigeur that Berthe and her sisters would receive artistic instruction. Visual art study became a significant part of Morisot’s upbringing, beginning with private lessons with Geoffroy-Alphonse Chocarne and then Joseph Guichard, who recognized Berthe and her elder sister Edma’s talents and suggested they look to professional careers—which was unheard of for women at the time. Guichard was instrumental in Berthe’s introduction to the Parisian art scene, and by 1864 she had made her public entry into the prestigious Paris Salon, becoming a regular contributor to the annual exhibitions for over a decade.

Apart from their private instruction, Berthe and Edma were registered at the Louvre as copyists as early as 1857, participating in the form of art study that allowed professional copyists, established artists, amateurs, and students an opportunity to learn by emulating old master paintings. This practice was invaluable to aspiring female artists who were excluded from academic instruction until 1897, unlike their male counterparts, including the free classes offered by the state-sponsored École des Beaux-Arts. Working at the Louvre also benefitted young women socially, offering rare public interaction with peers of the opposite sex, albeit under the strict watch of the ever-present chaperone.

It was at the Louvre in 1867 that Morisot and Edouard Manet were introduced to one another by the painter Henri Fantin-Latour. Even though Manet was a married man, they went on to develop an intense personal and professional relationship, Morisot soon replacing Victorine Meurent as Manet’s primary muse. She boldly accepted his invitation to pose for The Balcony in 1868 and was the model for over a dozen works over the next six years.

The suggestion that Manet and Morisot’s long-lasting friendship bordered on love is supported by Manet’s intimate portraits of her and the letters she wrote about him. But it is a doubtful possibility, given the sheltered reality of bourgeois young ladies of the day.

In his discerning portraits of Morisot, Manet captured her conflicted persona. Drawn to her intellect and appearance, his images of her suggest an empathic awareness of the personal and professional struggles she likely experienced. However his comment to a mutual friend, Henri Fantin-Latour, in 1868, the year they met, was slighting: “I agree with you, the demoiselles Morisot are charming. It’s too bad they’re not men. Nonetheless, they might as women serve the cause of painting by each marrying an academician and sowing strife in the camp of those old fellows.”

By the time Morisot befriended Manet, she had already exhibited her work at several annual exhibitions held by the Paris Salon, debuting with two pieces at only 23. She continued to exhibit at subsequent Salons until the mid-70s when she became involved with the young counter-culture artists orbiting Manet, who would later be known as the Impressionists. Morisot was the only female founding member of the group, sharing in the early controversy they attracted for their stylistically unorthodox paintings. She was there with them at the first Salon des Refusés, the subversive show of avant-garde works when Le Figaro‘s Albert Wolff referred to them as “five or six lunatics of which one is a woman… whose feminine grace is maintained amid the outpourings of a delirious mind.” These same artists constituted the core membership of the early movement, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Berthe Morisot.

As a movement, Impressionism situated itself in opposition to the rigid academic dictates of style and content. Artists associated with the group, including Cassatt, and Caillebotte slightly later, shared an interest in the ephemeral, impermanent depiction of modern life. Their conception of modernity included a belief in an artist’s free agency. They did not seek the sanction of institutions or the state and offered opportunities to those traditionally marginalized by them, namely women.

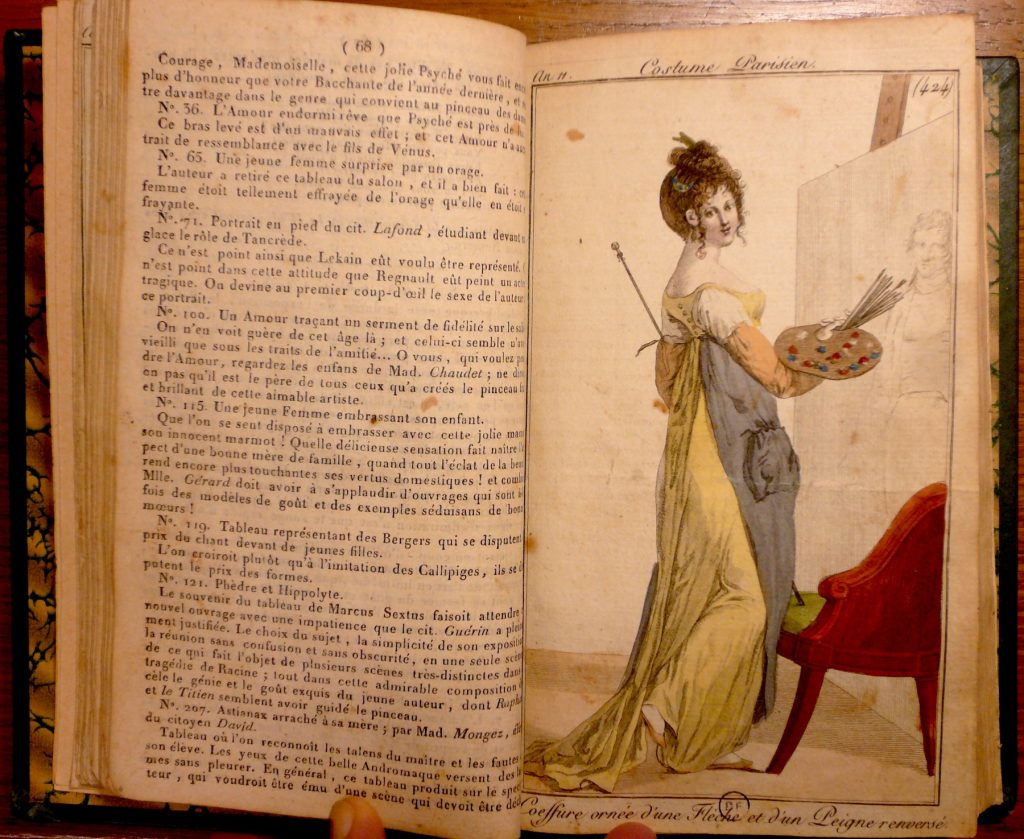

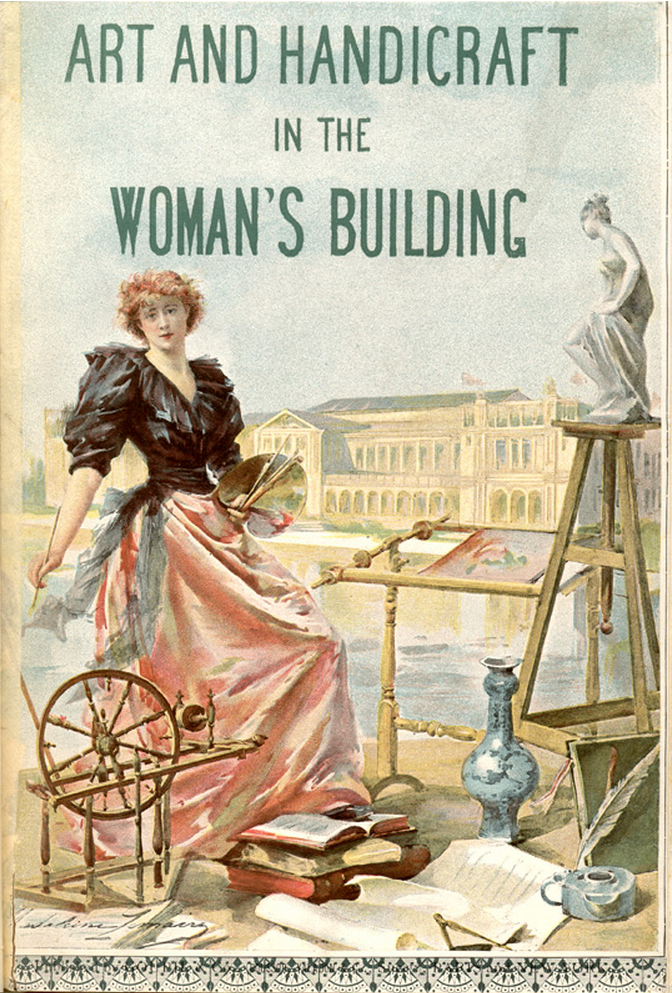

4.2

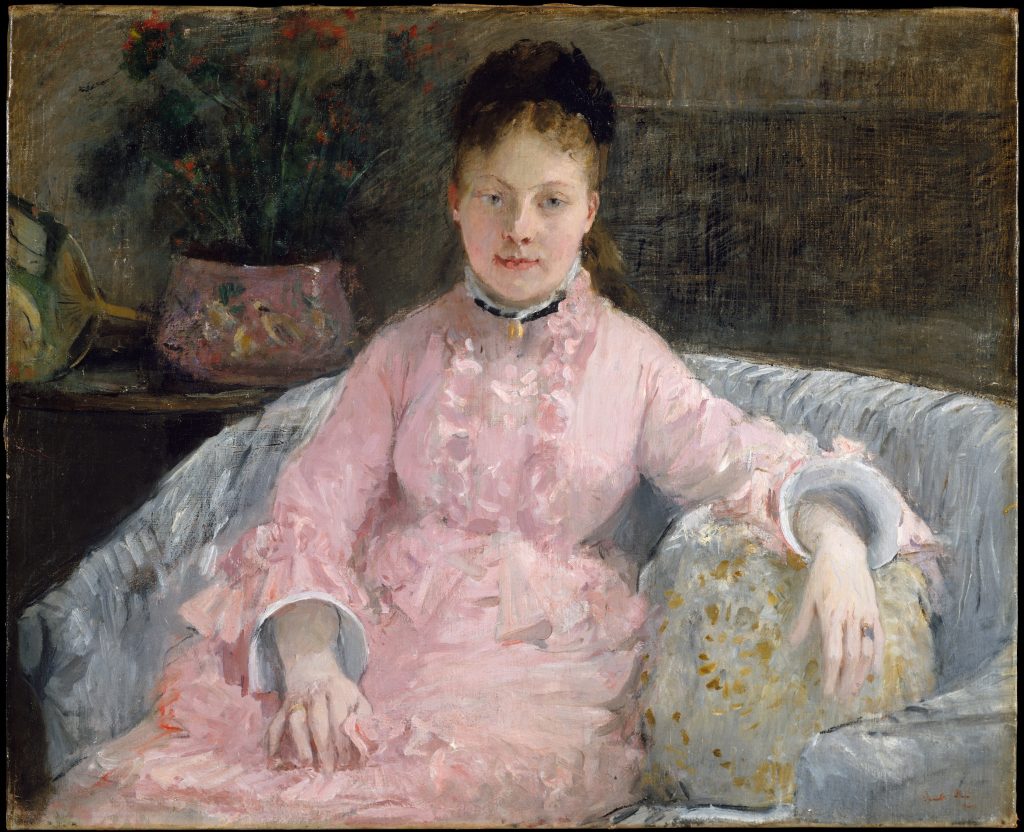

| Fashionable Subjects

Morisot’s modishness drew her to the latest designs from the Paris fashion houses and the increasing number of printed fashion magazines available to everyone. From the 1830s through the 1890s, magazines targeting a female audience included black and white engravings on almost every page. Expensive editions included two to three full-page hand-coloured plates. In France, La Mode illustré enjoyed a circulation of 40,000 in 1866 and 100,000 in 1890. Every virtue had its dress, every affection its token, each body its type of corset. In addition, the fashionable magazine models were set in familiar domestic spaces, evoking rituals of the home and underscoring the notion that female identity was a social construct.

Morisot was inspired by the fashion plates of journals such as La Mode illustrée, their up-to-the-minute dress designs, the models’ poses, the well-staged settings and sometimes even their compositional arrangements.

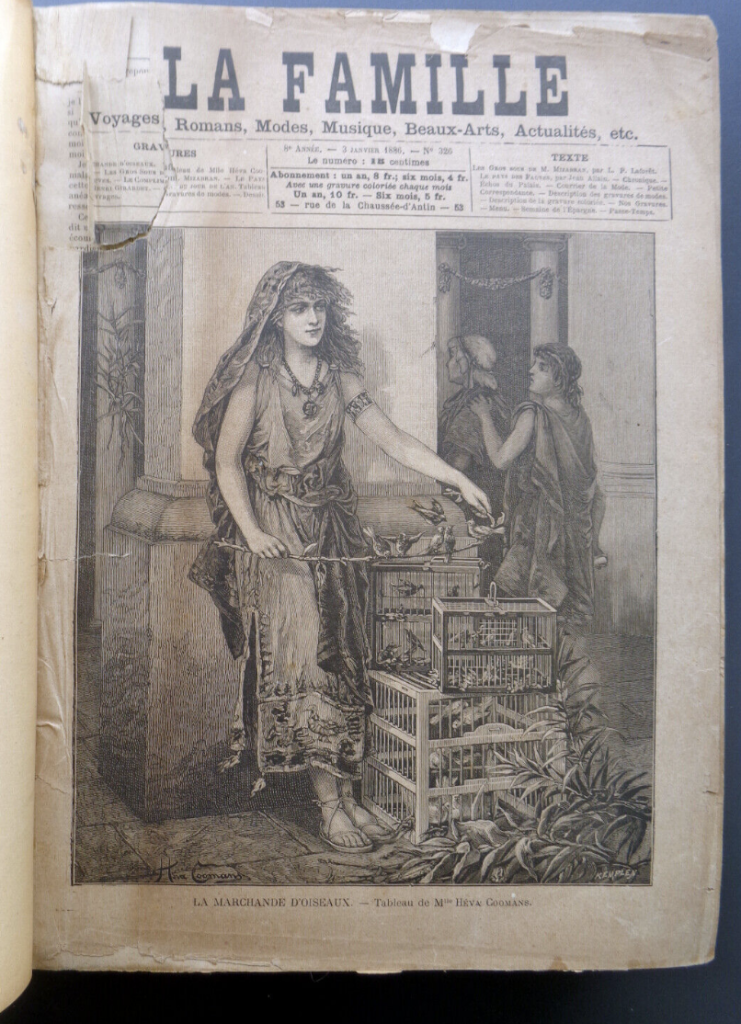

The French journals La Famille and Journal des dames et des modes were intended for upper-status female readers. Their illustrations were meant to affirm women’s lives by showing them pictures of ‘themselves,’ their actual lives, and their aspirations. They informed on fashion, sewing, embroidery and household management and published snippets of cultural news and social gossip. They also contained do-it-yourself guides for the artistically accomplished femmes au foyer helping them hone their skills within the seclusion of their home.

Tamar Garb argues in “L’art féminin: The Formation of a Critical Category in Late Nineteenth-century France” (Art History 12 (March 1989): 39-65), “… despite its avowed hostility to political feminism, for La Famille at least the figure of the woman artist did not remain, exclusively, the caricature of the fashion illustration. As the reproduction of women’s work on its covers testifies, there was a serious level on which the professional woman artist could be accommodated.”

Fashion magazines provided illustrators with ample work opportunities, and the genre developed a distinctive style.

Jules David, Comte Calix, and the Colin sisters, Adele-Anaïs Colin Toudouze and Héloïse Suzanne Colin, also known as Héloïse Leloir, for decades dominated fashion illustration and inspired painters.

4.3

| Sisterhood

Impressionist paintings of women by women provide a critical lens through which to examine the motivations of Morisot, Cassatt and others. The portrayal of of the ‘intimate moments’ shared by sisters, mothers, aunts, and friends in these artworks allows us to go beyond the surface representation of women and explore the painter’s female gaze. For female artists like Morisot, these intimate scenes became a means of interrogating their self-identity. Through their art, they could navigate the complex interplay between their public and private selves, offering viewers a glimpse into the nuanced aspects of women’s lives during that era.

Morisot’s sense of self was deeply entwined in her relationship with her sister Edma. They were constant companions until Edma’s marriage in 1869. An ethic of care and responsibility characterized their bond, which is discernible in Berthe’s portraits of Edma over the decades. Through their supportive relationship, Berthe struggled to establish an art career while her sister sought and found contentment in marriage.

Edma to Berthe, March 15, 1869:

“I am often with you, my dear Berthe. In my thoughts I follow you about your studio, and I wish that I could escape were it only for a quarter of an hour to breathe that air in which we lived for many long years.”

Berthe to Edma:

“This painting, this that you mourn for, is the cause of many griefs and many troubles. You know it as well as I do. Come now, the lot you have chosen is not the worst one. You have a serious attachment and a man’s heart devoted to you. Do not revile your fate. Remember that it is sad to be alone; despite anything that might be said or done, a woman has an immense need of affection.”

Edma’s mourning of her art practice was not without cause. Her artistic promise was equal to that of Berthe. They both studied and practiced art, and when Berthe’s portrait was painted, they were poised to exhibit at the annual Paris Salon for a second time.

The painting of Berthe shows competence and sensitivity, capturing the likeness and seriousness of the young artist at work. She is shown at her easel, her palette and brushes in hand. The painting is dark, but light strategically illuminates Morisot’s face and right hand, which holds a brush and painting materials. Her focused attention on her work displays her commitment and predicts the making of a professional artist.

4.4

| Familiar Subjects

The symbolic associations of women’s spaces with ornament, luxury, and intimate enclosure were firmly established in the 19th-century bourgeois imaginary. It was an equation employed in literary as well as visual narratives. Zola’s description of an interior in Au Bonheur des Dames illustrates this: « Le salon, avec son meuble Louis XVI de brocatelle à bouquets, ses bronzes dorés, ses grandes plantes vertes, avait une intimité tendre de femme … » (The salon with its flowered brocade Louis XVI furniture, its gilded bronzes and its big green plants had a woman’s intimacy…).

Given this historical context, The Mother and Sister of the Artist can be read as Morisot documenting Edma’s death as an artist and imminent birth as a mother. Her fingers fiddle with a cushion – they do not paint, draw, weave, or sew, all of which were socially suitable pastimes for bourgeois women. The juxtaposition of idle hands with the woven pillow – an object associated with delicate manual skill – makes this idleness more pronounced. Furthermore, her swollen and purplish left-hand contrasts with her white wrist, a symbol of how the physical symptoms of pregnancy – the swelling of hands and joints – could impair the dexterity required for painting… here Edma is shown as a biological vessel, partaking in the labour of waiting out pregnancy while the fetus grows to full term. As noted in August Debay’s 1862 guide Hygiene et physiologie du mariage, “The functions and demands of maternity begin at conception: as soon as a woman is certain of her pregnancy, she must no longer live for herself; every instant of her pregnancy must be dedicated to the fruit that she bears.”

…

While Morisot did not overtly show Edma’s expectant belly, she pointed to signs of pregnancy in numerous ways: her sister’s loose maternity dress; her confinement in her parents’ well-appointed apartment in Passy; Edma’s inaction; her propped-up foot and swollen hands; and the curves of the plush sofa that echo a pregnant woman’s rounded body and whose floral pattern symbolizes the fecundity of female bodies in bloom. Furthermore, the wooden table, with its distended leg and protruding curving top, creates a surrogate pregnant form, its links to fertility and femininity emphasized by the violet flowers in full bloom placed on the tabletop. Edma is shown following medical recommendations that were noted in numerous pregnancy guides for bourgeois women: she is not wearing a corset; she is sedentary; she is living in a clean home; and she is not exerting herself.

Morisot’s painting of the pregnancy experience was meant for a female audience. It was a bold choice of subject for the public Salon, and she was anxious about its presentation to the jury. She sought the advice of Manet, who was visiting the family on the final day of submissions. She would later describe the interaction to Edma,

“…he came at about one o’clock; he found it very good, except for the lower part of the dress. He took the brushes and put in a few accents that looked very well; mother was in ecstasies. That is where his misfortunes began. Once started nothing could stop him from the skirt he went to the bust, from the bust to the head, from the head to the background. He cracked a thousand jokes, laughed like a madman, handed me the palette, took it back; finally, by five o’clock in the afternoon we had made the prettiest caricature that was ever seen. The carter was waiting to take it away (to the Salon jury)…My only hope is that I shall be rejected. My mother thinks this episode is funny. I find it agonizing.”

Manet’s brushstrokes are evident in the somewhat heavier touch around Mme Morisot’s eyes, the minimalistic treatment of her fingers, and the broadly painted expanse of her black dress in thick impasto. Morisot came away from the patronizing experience determined to actively differentiate her work from Manet’s from then on. She expressed this openly in a letter to Edma in August 1871, “I am doing Yves with Bichette. I am having great difficulty with them. The work is losing all its freshness. Moreover as a composition it resembles a Manet. I realise this and am annoyed.”

When Morisot painted Edma’s second pregnancy, she captured a more mature and settled woman. Dressed in black, gazing directly at the viewer, she no longer appears reticent or regretful but conveys an attitude of composure. Mary Hunter writes:

Her intense gaze differs from her placated eyes in the earlier portrait, and her expansive dress fills the composition, creating a sense of severity through the solid black mass that is at odds with the frivolity of the decorative interior. Higonnet has argued that Morisot portrayed Edma in black in order to compete with Manet: she was demonstrating her ability to depict black fabric with the same skill as Manet did when he over-painted her work in 1869. The seriousness of Edma’s black dress is enhanced by the gravity of her expression. Her fixed eyes and tight mouth contradict the cultural stereotypes of a peaceful and joyful maternity, and hint at the contemporary moment in which the work was produced: the portrait was made in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War, after the loss of many French lives, and shows Edma pregnant with her second child.

By painting an assertively modern female subject, unapologetically pregnant, and whose bold look, crossed arms, and knitting at her side suggest that her work has been interrupted, Morisot transformed the nineteenth-century stereotype of a passive and naive pregnant woman into one of a serious, educated, and skilled haute-bourgeois mother. This work is also about expertise –maternal but also artistic and medical – and the seriousness and skill required.

4.5

| The Space Between

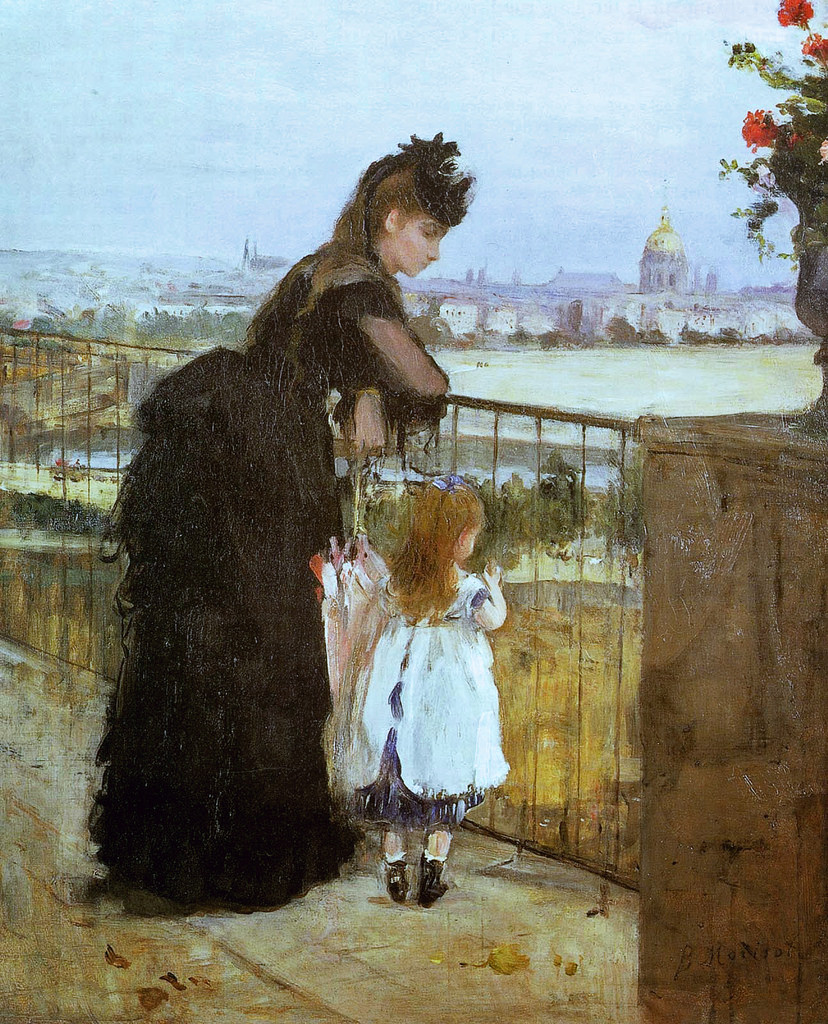

When Morisot expressed her frustration with a work resembling “a Manet,” she was likely referring to Woman and Child on a Balcony, completed in 1872. The female model in the painting is thought to be either Edma Pontillon or Morisot’s eldest sister, Yves Gobillard. The young girl is Yves’ daughter, Paule Gobillard, nicknamed Bichette.

Balcony exemplifies Morisot’s tactical use of pictorial space. She was drawn to in-between spaces such as verandas and balconies that were rife with pictorial potential and allowed her to explore the demarcations between private and public spheres of lived experience.

In this painting, the railing that bisects the picture is a compelling formal motif, which also serves as a metaphor for a fractured reality. As a conceptual device, it demarcates the boundaries between public and private spaces, between the areas of masculinity and femininity, the places women could access and those they could not. As Pollock has asserted, “Playing with spatial structures was one of the defining features of early modernist painting in Paris, be it Manet’s witty and calculated play upon flatness or Degas’s use of acute angles of vision, varying viewpoints and cryptic framing devices…[A]lthough there are examples of their using similar tactics, I would like to suggest that spatial devices in the work of Morisot and Cassatt work to a wholly different effect.” (Griselda Pollock, “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity,” in Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art, 62)

Here the woman and Bichette stand in the foreground at an oblique angle to the view and the viewer, obstructing the sweeping scene of Paris beyond the railing. More significantly, they are separated from the city by the balcony’s railing. It is interesting to observe that while the woman’s gaze is directed downward, ignoring the expansive view of the city, the young girl is looking out toward it. The compressed space and the subjects’ nearness to the surface of the canvas imply the painter’s proximity and further the sense of spatial enclosure.

Interestingly, while Manet’s The Railway, also known as Gare Saint- Lazare, seems to have borrowed several motifs from Morisot’s image, the paintings are distinctly different. His composition is articulated as a series of strong spatial and pictorial contrasts. Like Bichette, the little girl faces away from the viewer taking in the scene beyond. But the young woman does not look at her; she faces forward, directly at us. The model was Victorine Meurent, an artist and frequent model for Édouard Manet, who posed for several of his iconic paintings, including Olympia and Luncheon on the Grass. It was the last time Manet would paint her.

4.6

| Painting en plein air

While urban interiors and domestic scenes dominated Morisot’s images, Morisot’s ability to capture the play of light, her innovative use of colour, and her skillful brushwork are notable aspects of her artistic style. Painting Parisian women outdoors in various settings such as urban landscapes, parks, and gardens, allowed Morisot to explore different atmospheres and moods, showcasing her versatility as an Impressionist painter including the immediacy of her brushwork, and her experimentation with the concept of the finished and unfinished.

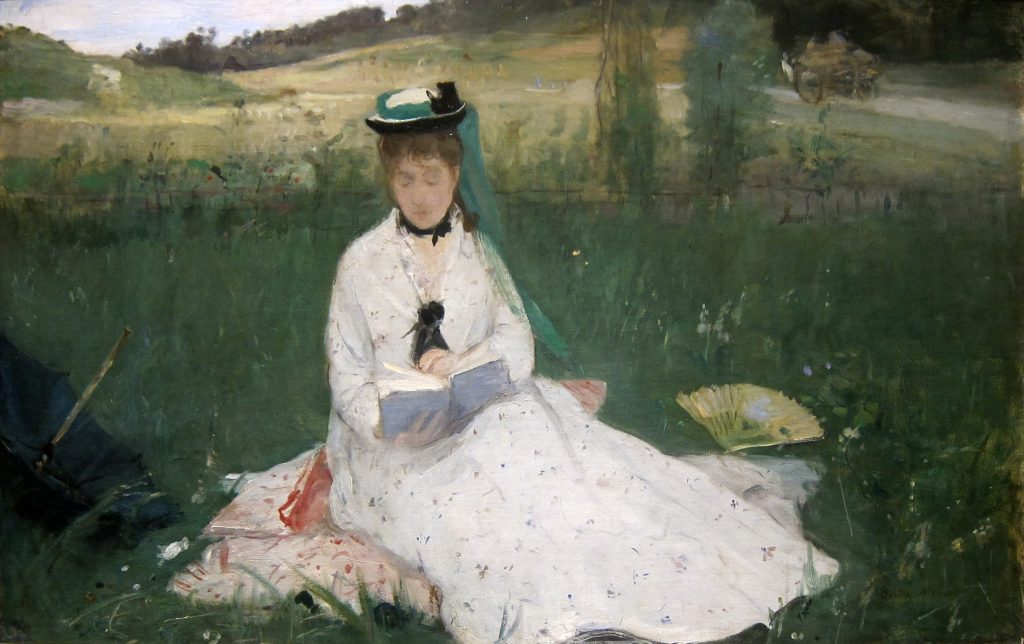

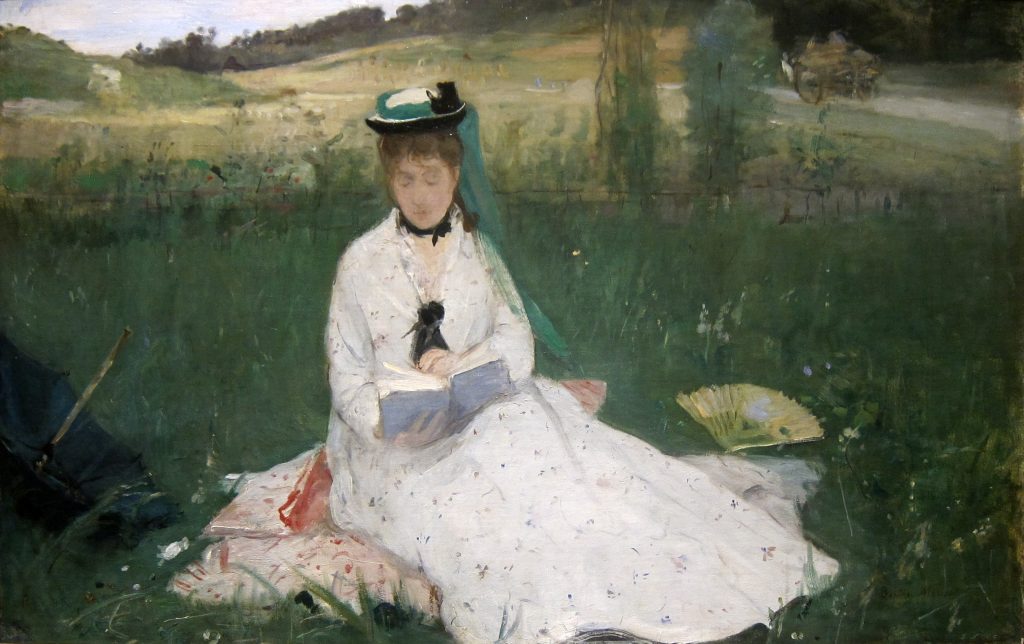

The freshness of her approach is seen in Reading, where Edma is pictured seated in an open meadow, wearing a white day dress embroidered with tiny flowers that echo the blooms dotted across the landscape. The sense of atmosphere, the loose brushwork, and the brilliant verdant setting demonstrate Morisot’s facility with the plein-air vocabulary of Impressionism.

Morisot’s introduction to plein-air painting was through her studies with Camille Corot, the leading artist of the Barbizon school. Corot anticipated the Impressionists, influencing many of them, but his pleinairism was more traditional, his palette more restrained, and his brushstrokes often controlled and careful.

Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes is said to be the first to expound on the benefits of plein-air painting.

Philip Conisbee writes in French Paintings of the Fifteenth through the Eighteenth Century, The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue (Washington, D.C., 2009): 409-410):

Through both his artistic practice and his theoretical writing Valenciennes holds a position of considerable importance in the history of landscape painting of the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries. In 1800 he published the influential treatise on landscape painting, Elémens de perspective practique, à l’usage des artistes, suivis de Réflexions et conseils à un élève sur la peinture, et particulièrement sur le genre du paysage … Much of this book is devoted to the detailed study of perspective. But Valenciennes was perhaps more influential for his advocacy of an almost systematic program of study by painting oil sketches from nature out-of-doors, which he believed was a better way for the young artist to understand nature’s myriad appearances and to train the hand and eye in capturing them in paint. This theory was based on Valenciennes’ own experience of painting oil studies in the open air during his last Italian sojourn between 1782 and 1785.

Corot’s importance to Morisot’s aesthetic development should not be underestimated. Christina Klotz Kales writes in “The Myths of Identity: Correcting the Legacy of Berthe Morisot” (PhD, Drew University, 2020):

Time spent with Corot left an indelible mark on Berthe’s vision as artist… He stressed the importance of understanding values in color with a gradation from lightest tint to darkest shade. He advised the girls to paint early in the day or late afternoon when refracted light would diffuse line and shape. They should paint, he advised, “when light is tempered, when useless detail disappears” (qtd. in Shennan 25). Corot became the source for her vision of light and pale palette, a remarkable shift from the darker Venetians she copied at the Louvre. “Nature” he said, “is the best counselor” (qtd. in Rouart 21). “It was Corot,” her family later remarked, “who taught her to bathe in air her landscapes, her figures, her still lifes” (qtd. in Shennan 46). It was Camille Corot, of whom an early critic said (his) “half-finished manner has at least the merit of producing a harmonious ensemble and an impression. Instead of analyzing a feature, one feels an impression” (Rewald, 331). Corot was the unacknowledged early father of Impressionism and his student Berthe Morisot would become one of its greatest practitioners.

Summer’s Day is an equally compelling example of Morisot’s interest in the effects of natural light and chromatic relationships. It was painted at the Bois de Boulogne, a public park in the 16th arrondissement in Paris, close to Morisot’s home and studio. Two fashionably dressed women are seated in a rowboat which floats in a shimmering lake of colour. The dabs of green and blue, and the hovering dashes of white, suggest the movement and flow of water beneath a bright sky. The colour palette for Summer’s Day was up-to-the-minute for its day. Tubes of paint were becoming available in the mid-nineteenth century, their portability allowing artists the freedom to paint out of doors. They also offered a range of unique pigments, seen here in the cerulean blue of one woman’s coat and the cadmium yellow of the ladies’ hats.

4.7

| Les Liseuses

Morisot was interested in more than just stylistic effects or in portraying snapshots of leisure life in her outdoor paintings. Her works demonstrate a knowing observation of the dimensionality of feminine experience in her era. Returning to the figure of Edma in Reading, one is struck by the painter’s empathic appreciation of the sitter, and Morisot’s respectful admiration of her literary sister. Edma is portrayed as an engaged reader, a modern woman of ideas, and an individual apart from her role as a wife and mother.

Kathryn Brown, in Women Readers in French Painting 1870-1890: A Space for the Imagination (Surrey: Ashgate, 2012), explains that female literacy, on the rise in Paris, was often a subject of discussion in literary works between the 1830s and 1860s. This interest inspired images of the liseuse in the visual arts, which brought to the fore concepts about female independence, education, and biology, fuelling the debate on women’s participation in cultural and political discussions beyond the domestic sphere.

In her introduction, Brown notes that depicting women reading “. . . was an effective way of communicating information about a woman’s intellect, social standing, personal relationships and private morality. These images of women reading, however, do not necessarily reflect the reality of rising literacy rates, but rather express . . . how women readers were constructed in the social imagination.”

Brown’s central argument is that images of liseuses evoked entirely contradictory interpretations. Reading could be seen as a distraction from a woman’s role as wife and mother or as a liberating act, one of the few available spaces for contemplation and the intellectual engagement of bourgeois women.

The ironies and contradictions encoded in images of female readers coincided with contemporaneous debates about educational reform for women. For some, reading signified corruption; for others, it evoked maternal and therefore civic duty.

The Belgian painter Antoine Wiertz, fell into the first camp, choosing to degrade the idea of women readers as indecent and slothful. His La liseuse de romans is a sexualized interpretation of the subject showing an undressed female figure extended on a bed seemingly enthralled by the novel she reads, and deriving obvious sexual pleasure from it. The viewer, observing her from a privileged vantage point at the foot of her bed, is positioned to watch an auto-erotic frenzy of her twisting torso through the mirror. A Satanic figure appears at the edge of the bed that appears to be supplying her with books and more books.

Wiertz’s La liseuse suggests the menace of “bad novels” as fictionalized in Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1857). “Emma wanted to know what the words felicity, passion, and ecstasy meant exactly in life; those words which had appeared to her so beautiful in books.” But in the end the knowledge she gained and the lovers she took led to her ruin.

Janis Bergman-Carton explains in The Woman of Ideas in French Art, 1830-1848, that the woman of ideas found her public during the rapid growth of the popular press between 1830 and 1848.

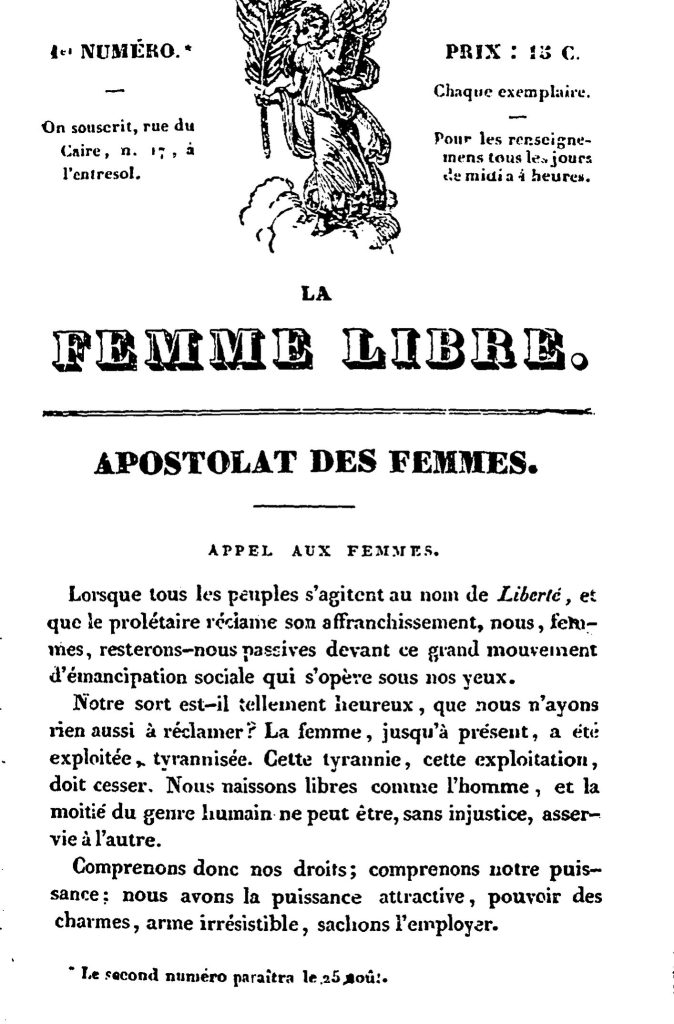

Bergman-Carton summarizes the creation of literary avenues for women authors in La Femme libre, Le Journal des femmes, Gazette des femmes, and La Voix des femmes, among others. She explains that the period between 1830 and 1848 was when female literary and political activity flourished. She then considers the caricatures in the popular press that portrayed these women as deviant and dangerous.

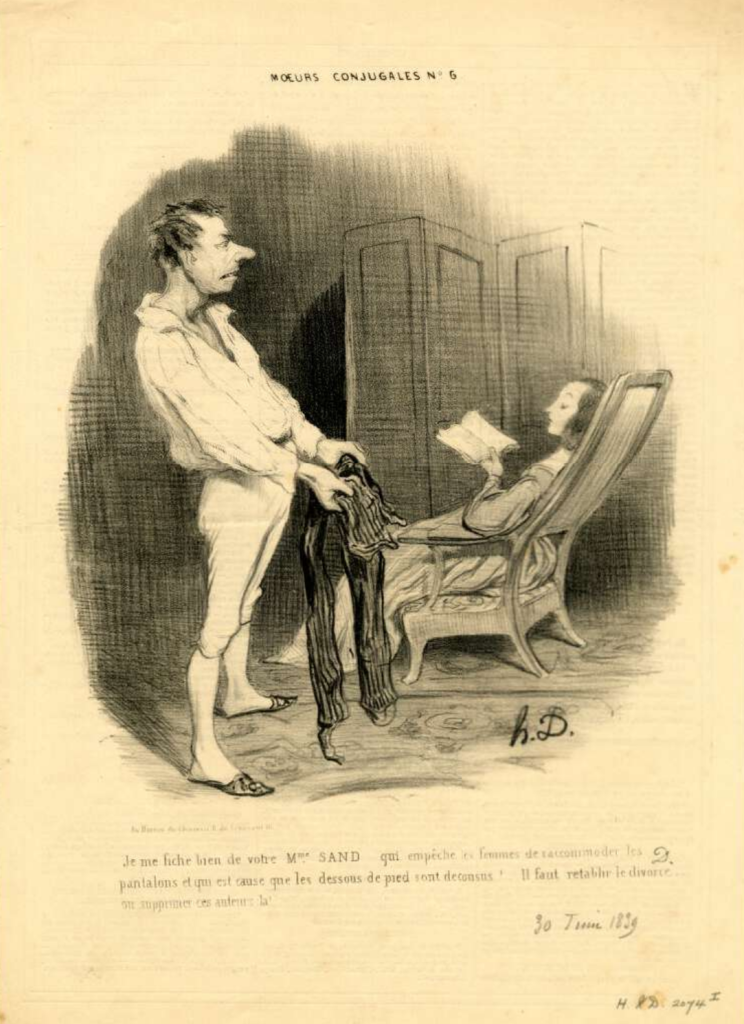

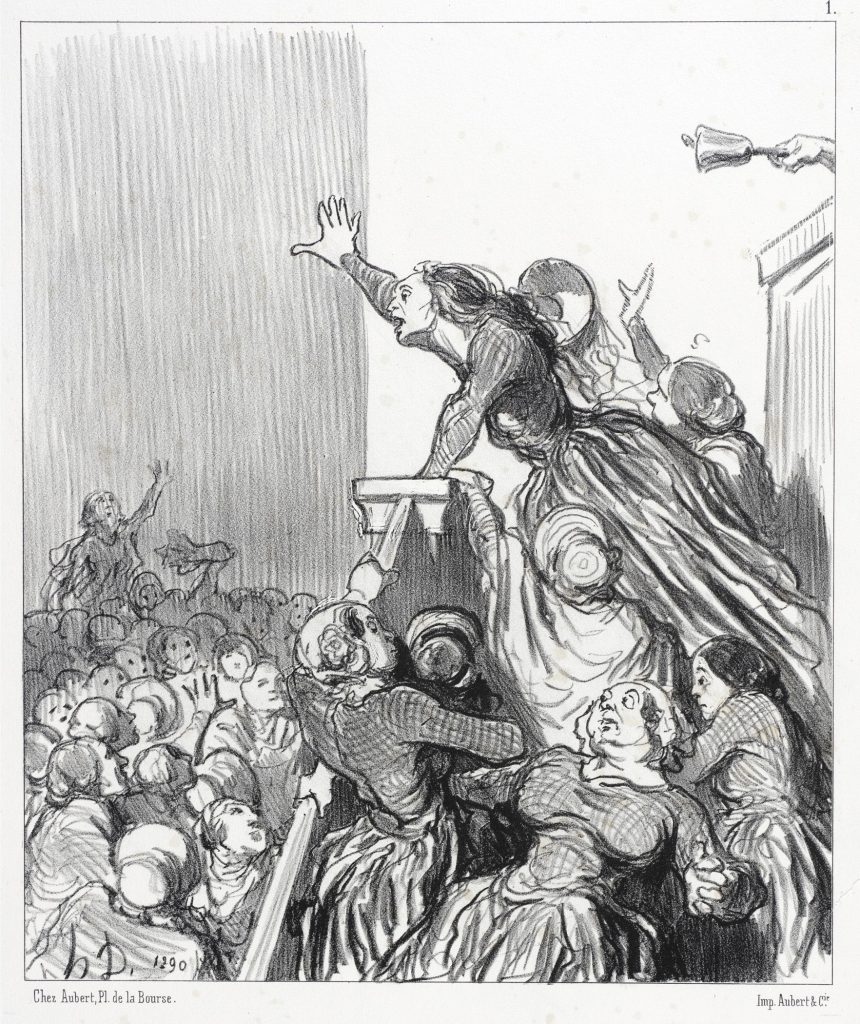

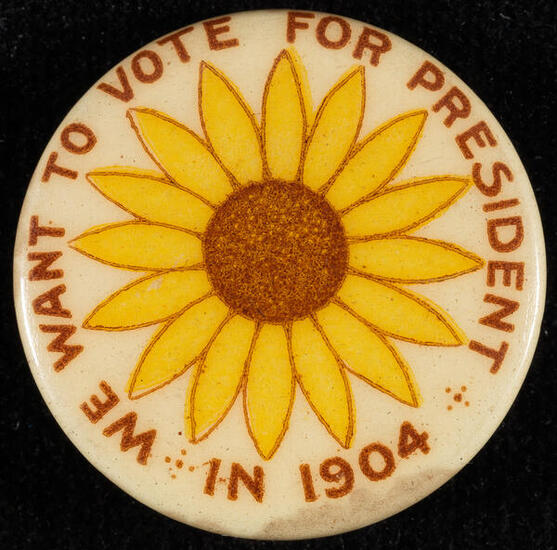

Between 1837 and 1849, Honoré Daumier produced several series of lithographs of women intellectuals. He was no advocate of female equality, scorning professional women and activists unmercifully in his prints. His caricatures savagely attacked middle-class, “bohemian” women who dared demand the right to vote, divorce or lead creative professional lives. The societal caricature of feminism generally centred on the abnormality of women who fought for equal rights. Daumier regarded and portrayed the female intellectual as a woman without physical appeal.

In 1948, Daumier produced his Les Divorceuses (women for the right of divorce), a series of six prints which appeared in the Charivari, an anti-feminist publication, from August to October 1848.

In this image, the composition is divided in two by a sloping diagonal banister, one area predominantly black, the other white. The female orator figure’s outstretched arm moves into the darker space, creating a powerful juxtaposition against the judge’s bell, which disappears into the background. The violent gesturing of the orator, her wild hair and her shouting mouth signify an outburst. The crowd of women on-side raise arms and voices in solidarity. Daumier was alluding to the harmful notion that women scream, create disorder and sow confusion, and the series suggests the furor of feminism at large.

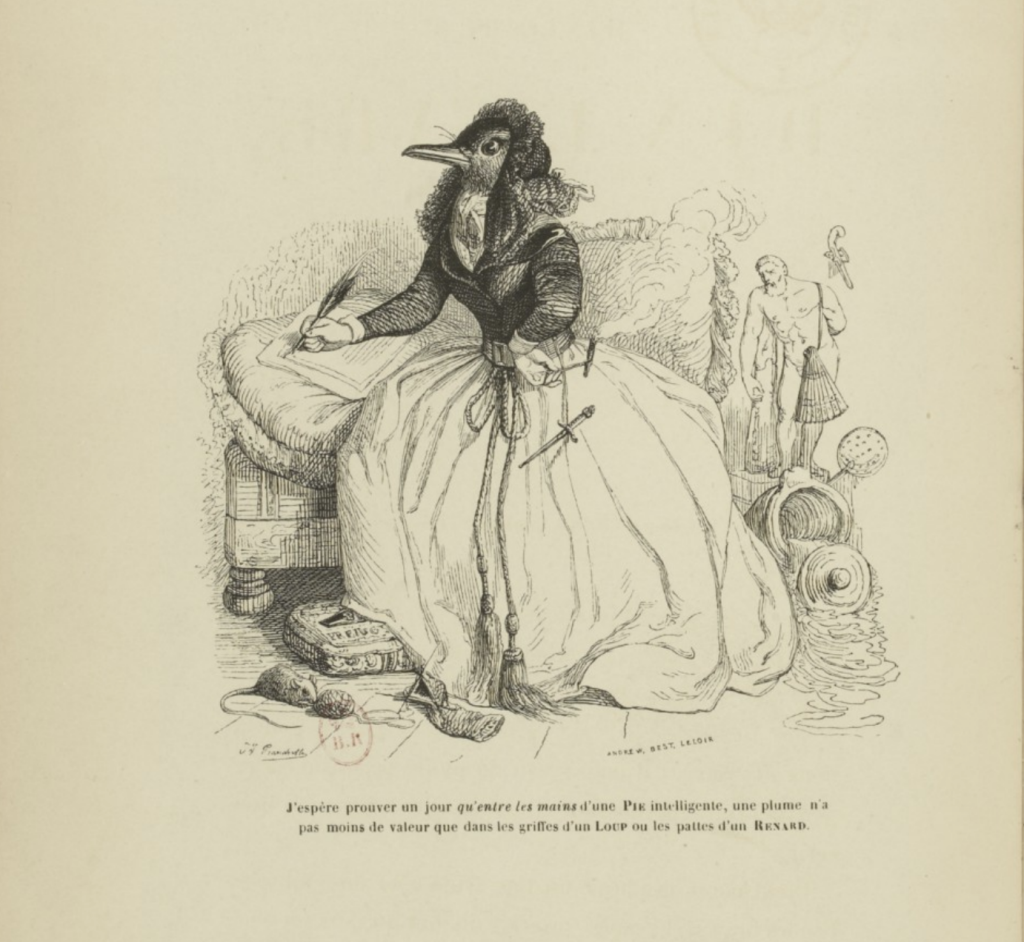

Other artists also caricatured women intellectuals. The image by the caricaturist Jean Ignace Isidore Gerard (who published under the pseudonym Grandville) illustrating P.J. Stahl’s Story of the Hare shows a femme-auteur majestically perched on a thickly cushioned sofa, looking up from her writing to gather her thoughts. With a pen in one hand and cigarette in the other, she contemplates her next words. The emasculating potential of her endeavour is signified by a dagger that hangs loosely from her belt and points towards her genital area.

4.8

| Visualizing Motherhood

Berthe Morisot’s The Cradle was the first image of motherhood that she painted, marking the start of her interest in a subject to which she would return frequently throughout her career. It shows Edma gazing over her sleeping daughter, Blanche.

Edma’s gaze and her bent left arm echo her baby’s sleeping pose. They are connected through a painterly diagonal formation. The cradle’s filmy netting acts as a screen, enhancing the loving bond between mother and daughter. The soft blues, grays and warm golden tones of the image create a sense of calm and comfort. This is a highly intimate scene, unlike the objectified and idealized scenes of similar subjects by many of her male contemporaries. It suggests the psychoanalytic mother-child relation of being in a world of their own and the role and reality of motherhood. Edma expresses love and joy but also the fatigue that is part of the experience of motherhood.

Morisot’s images of motherhood stand apart from the idealized mother and child images by, for example, William Bouguereau, whose Young Mother Gazing at her Child is described by the Metropolitan Museum of Art as follows “This doting mother in picturesque dress and her angelic offspring are two of many such figures that Bouguereau painted with an eye to the international market.”

“ … the scene is highly similar in subject and composition to Breton Brother and Sister, also dated 1871 (hanging nearby), and both works were bought by New York collectors—a testament to the popularity that the artist’s scenes of ‘princesses dressed up as milkmaids’ enjoyed in America.”

The entry for Breton Brother and Sister reads:

Based on sketches Bouguereau made while summering in Brittany in the late 1860s, this picture was completed in the artist’s studio in 1871. His young models, posed in traditional Breton costumes, epitomize the ideal of virtuous and attractive peasants living a simple life in close contact with nature. American collectors quickly snapped up this type of scene, earning Bouguereau fame and fortune.

Morisot painted Edma from the time of her sister’s wedding in 1869 until she herself married Eugene Manet (brother of Edouard Manet) and gave birth to their daughter, Julie.

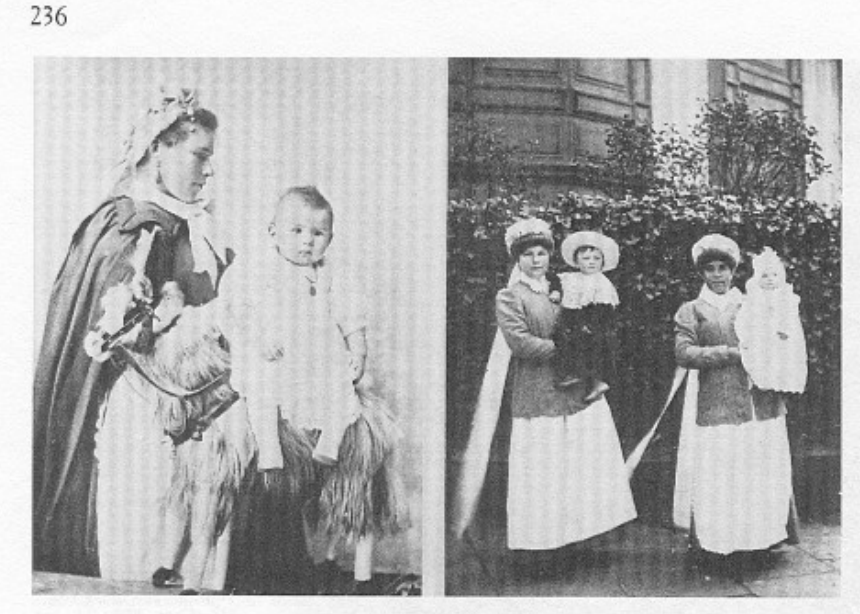

In The Wet Nurse, early babyhood is represented in all its fullness, although Julie is not nursed by Morisot but by a seconde mère, a wet nurse, as was common among the upper classes.

For example, Degas’s At the Races in the Countryside (1869) depicts the trio of husband, wife and wet nurse. In the driver’s seat of the carriage, Paul Valpinçon, a friend of Degas, turns to look at his wife, holding a parasol, and his son Henri, asleep in the lap of a wet nurse whose breast is still exposed.

Linda Nochlin writes in “Morisot’s The Wet Nurse” (Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, Norma Broude, and Garrard, Mary D., eds. Westview Press, 1992, 231-245) that the painting represents motherhood in the most obvious of ways, but the mother in the scene is a seconde mère or wet nurse. She is a worker, earning her wages as a member of a flourishing industry. Furthermore, she is being gazed upon not by a man (husband, artist, viewer) but by a woman, an artist who is also the baby’s natural mother. The work is unusual and bold, in its subject of a woman painting another, nursing her child.

Wet nursing, Nochlin explains, was a large-scale industry in 18th and 19th century France. Urban families whose wives worked outside the home, such as shopkeepers, or artisans, usually sent their infants to the country to be nursed. Because sanitation violations were excessive and financial arrangements so random, the government was forced to step in and regulate the industry in 1874.

While the upper classes also participated in this widespread custom, they did not need to rely on state-sanctioned individuals; they could hire live-in nurses to look after their baby’s needs. These nurses frequently came from Morvan, a country region considered prime wet-nurse territory. Few, if any women of the upper classes would have dreamed of breastfeeding their children, and only a limited number of working-class women had the opportunity to do so.

Nochlin explains that the problems around this industry were made to link to women’s neglect of their duties. The Grand dictionary universel du XLXe siecle, in an article on mortality cited from the work of M. Husson, outlines the tragedies in Paris:

… an average of 53,921 children born, of which 33,872 remain in Paris with families; 2,031 are placed in nurse’s care by municipal government; 3,018 are placed in foundling hospices and 9,000 are placed by private bureaus. Of the 33, 872 infants who remain in Paris with their families 8,250 die in their first year, 24.36 of 1000; the mortality of infants placed by the municipal government is 29.80 out of 100; as for the mortality of the infants placed by the small bureaus much greater…

The article ends on an accusatory note targeting females: “The best thing to do, or at least attempt, would be to persuade, even force, if need be, those mothers who are physically able to do so to nourish their children themselves…The whole problem stems from the rebellion of women against breast feeling. A means must be found of recalling them to their duty.”

Apart from its bold, modern subject, The Wet Nurse displays a freedom of brushwork that is quintessentially impressionistic, so fluid that it resembles a watercolour painting. The boundaries between the figure and landscape setting are blurred in a vaporous atmosphere, a way of painting that became emblematic of Morisot’s fusion of a figure and the natural world.

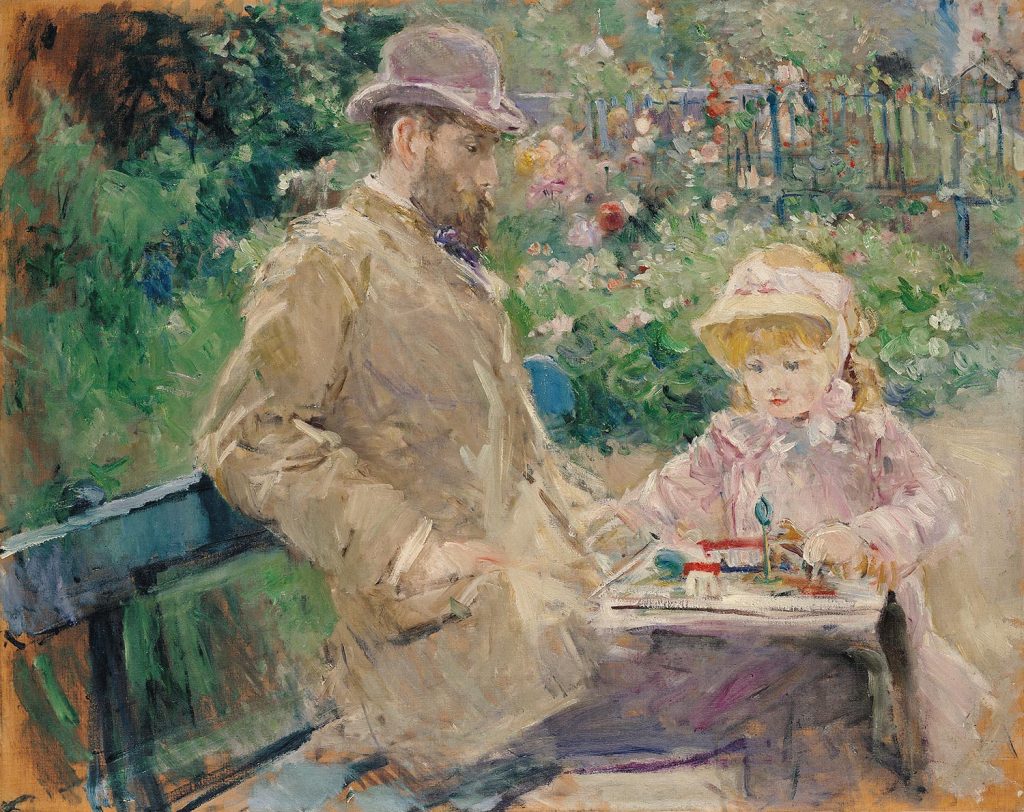

Morisot’s painterly freshness and the facility of her execution is seen again in Eugène Manet and his Daughter at Bougival, a scene set in the garden of a rented house in Bougival where the family spent their summers between 1881 and 1884. Morisot’s images of Julie she painted there, are the most radical reformulations of childhood imagery of the time. In this image, Julie takes on the role of the narrative agent. In contrast, her father takes on that of a subsidiary figure, an inversion of the relationship, pictured or otherwise, of parent and child. Absent as well, are the pretty, formulaic features that mimic dolls’ faces, replaced by a uniqueness of expression commonly unseen in paintings of children.

An easy naturalism characterizes Eugène Manet and his Daughter at Bougival. It is evinced in the lyricism of the scene and the ephemeral qualities of colour and form. The emphasis is on regular activity rather than striking a pose. Julie is not prettily playing with a doll but involved in a real game with her father. Morisot had the unqualified support of her husband, Eugène Manet, to pursue her artistic career, and one senses the supportive relationship in the easy gentleness of the work.

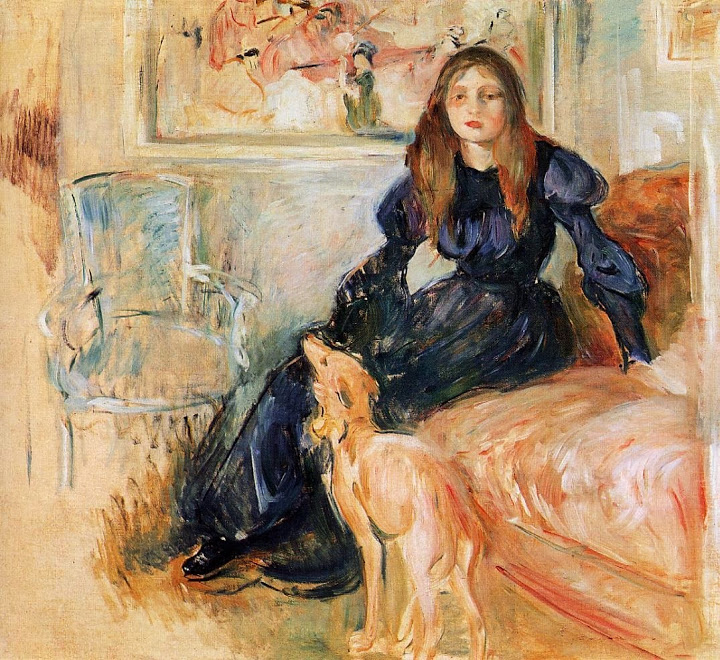

In 1893, in a painting entitled Julie and her Greyhound Laerte, made shortly after her husband’s death, an empty chair appears as evanescent. At first it reads as an omission, becoming almost nothingness, but its presence is so compelling that one interprets it as emblematic of Eugène’s absent presence within the space.

In a self-portrait with her daughter from 1885, Morisot fully looked at herself as a painter, a person, and a mother. She did so by constructing an image that visually triangulates the relationship between mother and daughter, independent selfhood, and the activity of painting. In contrast to the usually banal images of women as mothers, Morisot’s self-image strategically allowed her to celebrate maternity while also laying claim to her professional and personal identities.

4.9

| Looking Female

Morisot appropriated the mythological figure of Psyche, a goddess of outstanding beauty, as a topos to represent her daughter’s awakening sexuality. In The Psyche Mirror, the adolescent Julie is picturing standing before a mirror. While the work may have had voyeuristic potential, the young woman’s self-contemplation dissuades such a reading. The painting’s intimacy, palpable privacy, and the figure’s proximity to the viewer all posit a different interpretation. We are witnessing a woman looking at another woman who looks at herself. Psyche expresses the concept of self-looking and the act of mirroring: the mirroring of self, the mirroring of the gaze.

Morisot produced a series of toilette paintings engaging with the concept of gazing, looking and being looked upon.

Her images of ladies at their toilettes contain reflective surfaces such as mirrors, glass windows and pictures that offer glimpses of multiple perspectives. Just as Psyche stood before a chevalier mirror, the figure in Young Woman Powdering her Face sits before her vanity mirror, looking at her reflection. At the same time, behind her a wall of glass-framed pictures offers refracted images of the overall scene. Multiple references to looking encourage contemplation on how women are seen and how they see themselves. The notion of looking and seeing also speaks to the act of painting, a process that offers sensual pleasure and the desire for public approbation. The woman painting her face and the woman painting her both suggest Baudelaire’s: “She must paint herself to be adored.”

Claire Moran writes in “Minor Intimacies and the Art of Berthe Morisot: Impressionism, Female Friendship and Spectatorship” (Journal of the Society of Dix-Neuviémistes 25 (2021):137-157): “Middle-class women, like Morisot were ‘urged to create sanctuaries for their children within their homes and to take a new, involved interest in all aspects of their upbringing and education’ (Todd 1995, 101). Morisot would also develop this theme in the series of images of her daughter Julie, which constitute “her most extensive pictorial project’ (Higonnet 1992, 212)… Morisot’s works were not destined for public display and ‘home was where she wanted her work to remain” (Higonnet 1992, 81). Her pictures were intended to be shared but with select audiences, friends and family members and occasionally trusted collectors.”

In family homes, Morisot’s pictures were hung where they fit, up to the ceiling, or along staircases, in a dense mosaic alongside other family pictures: pictures by Morisot’s sister, daughter, nieces, husband, brother-in-law, son-in-law, father-in-law, pictures made by friends and given as gifts, […] In a private world they hang among images unified less by style or period than by family meaning: images of a grandmother, testimonials to a mother’s relationship with her daughter, tributes from one friend to another, carriers of family history. (Higonnet, 1992, 83).

Morisot painted about 150 images of her daughter in the sixteen years following Julie’s birth in 1878 until her death in 1895. Morisot caught influenza while tending to Julie’s infection and succumbed to the disease within days. A year after her death Julie, Morisot’s mother and her Impressionist friends organized a memorial exhibition. Over four hundred oil paintings, pastels and drawings, many previously unseen, were put on view. Degas, Renoir and Monet assisted in the hanging of the exhibition and the catalogue was written by the poet and critic Stephane Mallarmé. Mallarmé described the artist’s charm and elegance, the evening salon gatherings, her painting practice and her role as a loving mother. He spoke of Morisot’s relationship with Edouard Manet, and acknowledged the character of her later portraits of women, and her outdoor scenes reminiscent of the light and elegant touch of eighteenth-century artists. In the end, however, Mallarmé was unable to acknowledge the uniqueness of her contribution to art because she was female, despite the fact that his concluding remarks positioned her as a recognized Impressionist artist.

Over the last decades, Morisot’s significant contribution to art history has been fully recognized, her struggles and successes spurring numerous scholarly investigations and exhibitions. As Christina Klotz Kales summarizes in “The Myths of Identity: Correcting the Legacy of Berthe Morisot” (PhD diss., Drew University, 2020, 25):

Her achievement would rely on three strong pillars. These factors underscore the uniqueness of Morisot’s choice of an unlikely profession for a woman of her social class as well as an understanding of how she came to develop and pursue this choice. First, she initially enjoyed the full emotional and financial support of her family, both necessary to develop the independence necessary to express herself artistically. Second, she benefitted from a grounding technical education as an artist that would have been the envy of many of her male peers. Finally, she lived her entire life in Passy, a Parisian suburb dominated by the great natural expanse of the Bois des Boulogne. The park became both her source of inspiration and a reserve of quiet and calm. She would paint here throughout her life always reveling in her deep connection to nature and capturing the effect of transient light on canvas.

Morisot was a radical artist in her lifetime. If she could not access parts of Paris open to her male colleagues, she focused on the world that she knew, but she did so with innovation and daring, producing pictures that broke with the stale academic dictates of the day and engaged the emerging visual vocabularies of the avant-garde.

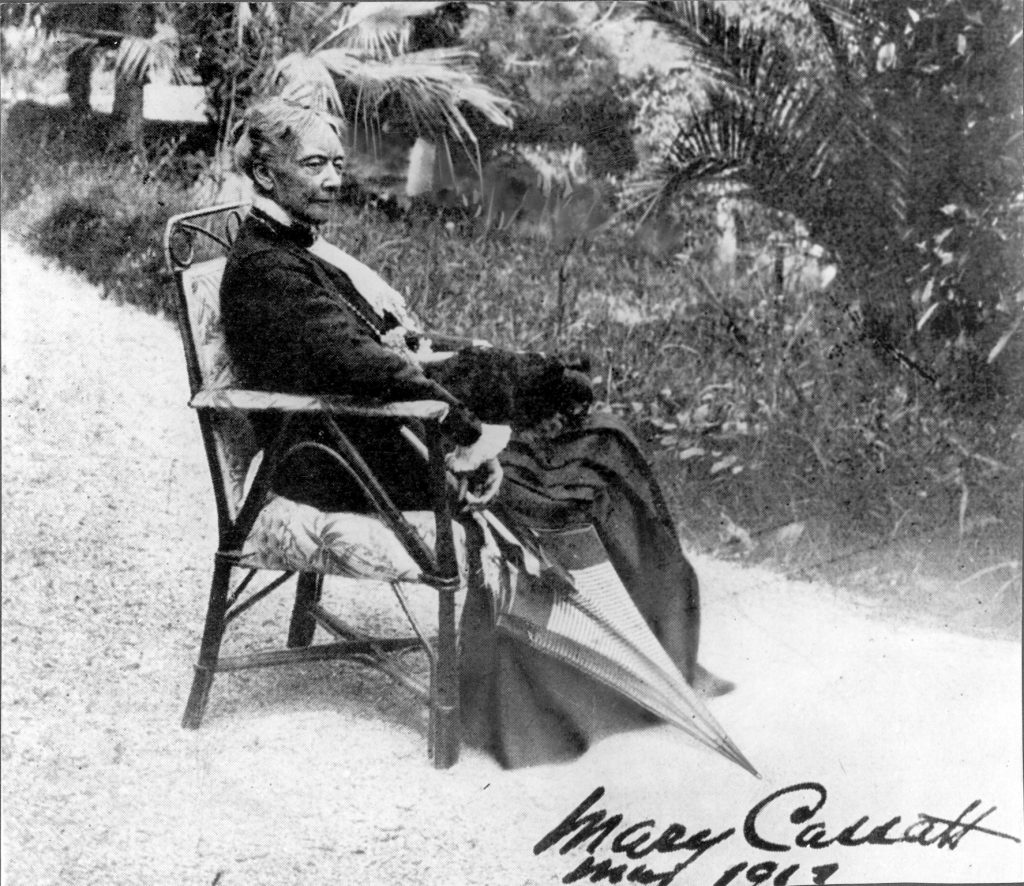

MARY CASSATT

4.10

| An American in Paris

Mary Cassatt was the only American female artist associated with the French avant-garde. She was born in Pittsburgh on May 22, 1844, to a prominent and cultured family. The Cassatts were believers in the educational importance of travel, which they did as a family in her girlhood. Cassatt enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts at sixteen, against her father’s wishes. The patronizing male environment was a disappointment. She set her sights on Europe again in defiance of her father, who claimed he would rather see her “dead than living abroad as a bohemian.” When she left for Paris in 1866, she did so chaperoned by her mother and family friends.

The young Cassatt spent her days traveling across Europe, studying the works of the Old Masters and independently establishing her unique style. Back in Paris, barred from attending the École des Beaux-Arts, Cassatt studied in private with Jean-Léon Gérôme and registered as a copyist at the Louvre. She befriended French painters such as Charles Joshua Chaplin and took instruction from Thomas Couture. But, like other upper-class women, she could not go about independently in Paris.

In her journal, the Russian artist Marie Bashkirtseff who was studying in the French capital at the time, described the frustrations felt by a generation of practicing female artists and her awareness of the freedoms she was denied.

What I long for is the freedom of going about alone, of coming and going, of sitting in the seats of the Tuileries, and especially in Luxembourg, of stopping and looking at the artists’ shops, of entering churches and museums, of walking about old streets at night; that’s what I long for; and that’s the freedom without which one cannot become a real artist. Do you imagine that I get much good from what I see, chaperoned as I am, and when in order to go to the Louvre, I must wait for my carriage, my lady companion, my family.” Marie Bashkirtseff, Marie Bashkirtseff. The Journal of a Young Artist: 1860-1884 (London: Virago Press, 1985).

The Paris Salon accepted Cassatt’s The Mandolin Player in 1868, no small achievement for a young American female artist, and it set her on her path. When the Franco-Prussian war broke out, she was forced to return to Pennsylvania temporarily but returned to Paris to settle in 1872. She aligned herself with the circle of Parisian avant-garde artists, and, at Degas’s invitation, began exhibiting with the Impressionists in 1879. Cassatt’s painting style and subject matter altered dramatically through her association with Impressionism. She abandoned costumed genre painting in favour of ordinary subjects painted in fresh colours and loose brushstrokes.

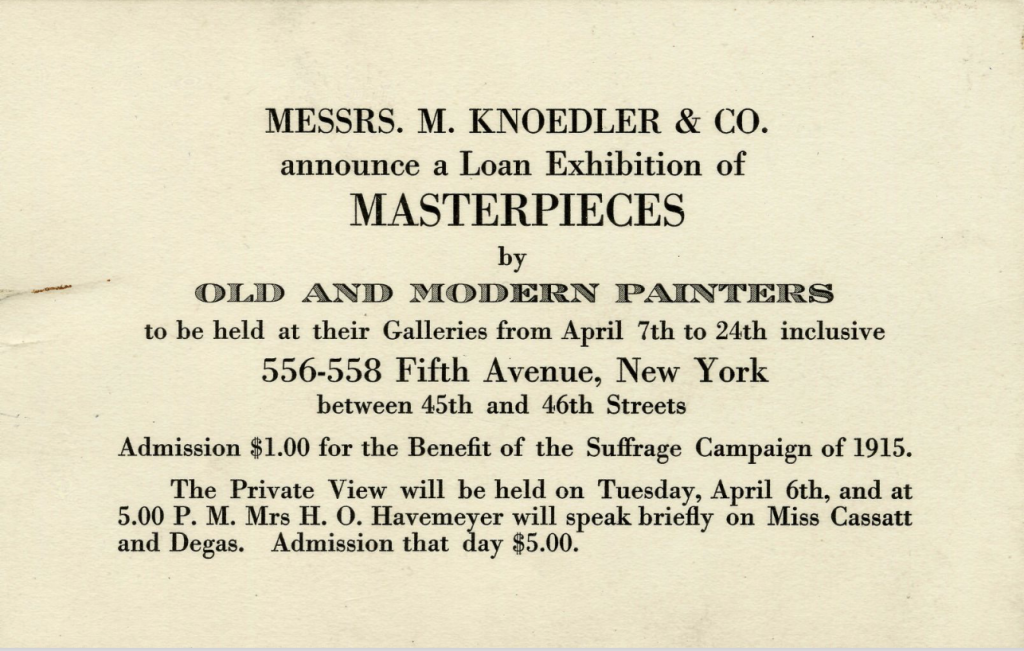

In 1886 she was included in the first major Impressionist art exhibition in the United States, held at the Durand-Ruel Galleries in New York.

Paul Durand-Ruel purchased over 400 Cassatts, 1,000 Monets, 1,500 Renoirs, 800 Pissarros, 400 Sisleys, and about 200 Manets. He actively promoted an international interest in Impressionist artists through his art galleries and exhibitions in London, Berlin, Brussels, and New York.

The Mandolin Player is a dark genre piece which is strikingly different from her later paintings characterized by highly keyed colours and artificial spaces. But despite its naive quality and conventional style, this early work suggests the beginnings of an individualistic approach. Griselda Pollock observed that the painting “is not a straightforward genre painting for it is not a scene of peasant music-making, and the viewer is required to engage with two demands whose tension produces the painting’s allure. The uncluttered directness of the figure’s presentation draws the eyes toward the paint itself, the broadly blocked paint of the white chemise as the light falls upon it, the carefully modulated muted reds of the sash that provides the only local colour, and the finely brushed, shaded face from which expressive eyes emerge to arrest the viewer’s appraisal of painterly finesse.” (Pollock, Mary Cassatt: Painter of Modern Women (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1998), 83-84)

4.11

| Modern Attitudes

Cassatt’s images of women reflected the genteel daily activities that were common to the privileged class. Her lush paintings and prints offered a rare feminine perspective within the male-dominated representations of everyday life. Her subject matter drew criticism, which she was aware of and conflicted about. But her professional ambitions did not prevent her from exploring the spaces of feminine leisure, which she did while engaging with new stylistic vocabularies that rendered them more relevant.

The sociability of her bourgeois world— the rituals around tea, the art of organizing domestic ceremonies—centred upon the “creation of atmospheres” as Dorothy Richardson in Revolving Lights Pilgrimage the seventh ‘chapter-volume’ of Pilgrimage, a series of semi-autobiographical novels published between 1915 and 1967 asserted:

Women are emancipated … Through their pre-eminence in an art. The art of making atmospheres. It’s as big an art as any other. Most women can exercise it, for reasons, by fits and starts. The best women work at it the whole of the time. Not one man in a million is aware of it. It’s like air within air. It may be deadly. Cramping and awful, or simply destructive, so that no life is possible within it. So is the bad art of men. At its best it is absolutely life-giving. And not soft. Very hard and stern and austere in its beauty. And like mountain air. And you can’t get behind it, or in any way divide it up. Just as with ‘Art.’ Men live in it and from it all their lives without knowing … the thing I mean goes through everything. A woman’s way of ‘being’ can be discovered in the way she pours out tea. ( London: Virago Press, 1979, 3, 257)

Beyond social aspects, the women Cassatt painted, especially her mature female subjects, often exuded a sense of composure and authority. Mrs. Riddle, in Lady at a Tea Table, is a portrait of a wealthy American, Cassatt’s mother’s first cousin, presiding at tea, a gilded blue-and-white Canton porcelain service set in front of her. She appears monumental, autonomous, indifferent to both painter and viewer.

Cassatt articulates the scene in an impressionistic, sketch-like style, yet it reads as complete and self-contained. She demonstrates an appreciation for the serious artistry of creating ‘occasions’ by depicting the lady at the tea table with character; she is neither seen as frivolous nor superficial. The placement of the sitter’s upper body in relation to the pictured frames behind her solidifies her bearing and her placement within the scene. It also calls attention to the formal dynamics at play, the relationships between the rectangles within the painting and the rectangular shape of the canvas. Cassatt sees, and appreciates, that her sitter’s interests —manipulating the tea things, arranging her clothing and decor, and overseeing a meticulously run, aesthetically pleasing household—contained analogies to her own process and commitment to painting, the constant honing and imaginative decision-making required to succeed.

Cassatt observed the power inherent in such a role and expressed it. Mrs. Riddle exudes authority; she is formidable, and modern.

It was not a coincidence, writes Anne Higonnet in her in-depth analysis of Lady at a Tea Table “A Painting by Mary Cassatt and Its Challenge to the Social Rules of Art” (A Companion to Impressionism, André Dombrowski, ed. (John Wiley & Sons, 2021), 219-233), that:

The offending portrait painted by Cassatt had a lot in common with the portrait Degas painted of Cassatt around the same time. His portrait paid tribute to the same modern, professional, ambiguously gendered qualities with which she had invested Lady at the Tea Table. He shows Cassatt offering images to the world outside the painting, which identify her with modernity, because they are photographs, identifiable by their format as carte-de-visite photographs. Degas here makes another of Impressionism’s puns between masculine and feminine meanings by representing the way Cassatt holds the photographs as if they might be either a hand of cards or a fan.

Cassatt disliked this portrait of her by Degas, which helps us understand why Riddle and her daughters refused Riddle’s portrait, as well as why Cassatt claimed she was mortified by it. “I felt that I never wanted to see it again. I did it so carefully and you may be sure it was like her – but – no one cared for it.” Perhaps Cassatt herself thought she had gone too far. The unconventional role that Cassatt had asserted as the author of Lady at the Tea Table looked repugnant when she saw it ascribed to her as the subject of a portrait. Cassatt treated both portraits in the same way. She kept them, but hid them, so no one could see them.

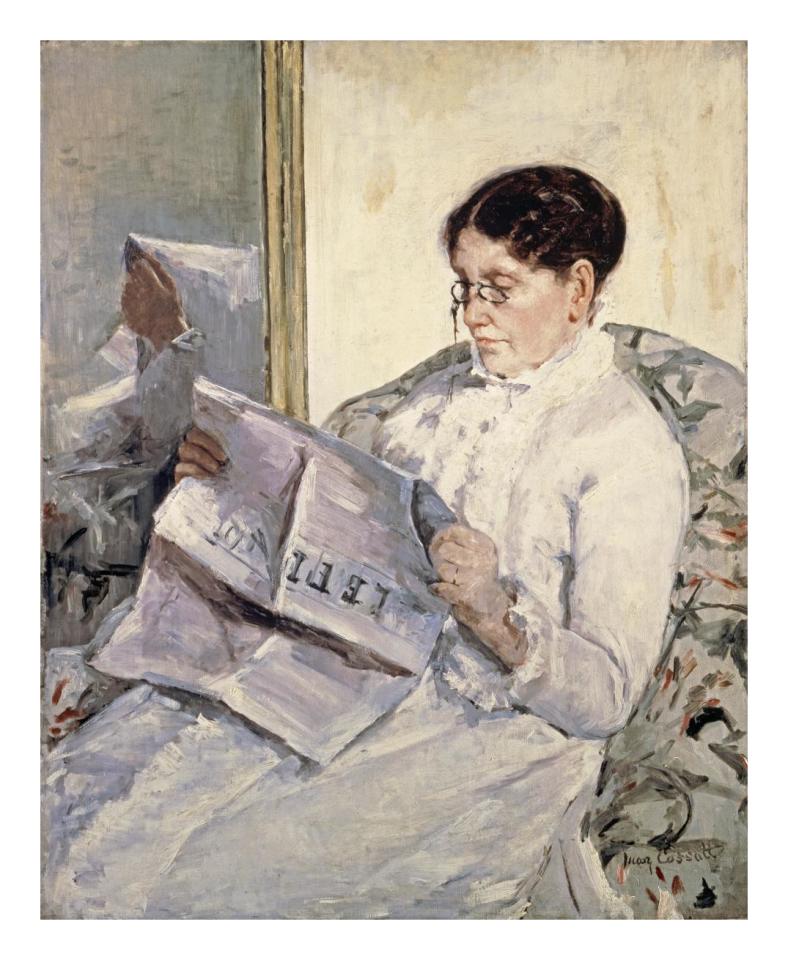

Lady at the Tea Table was completed in 1885, seven years after Cassatt painted Reading Le Figaro, a portrait of her mother, Katherine Kelso reading with great concentration. Le Figaro was a serious, politically and literarily oriented publication, and Cassatt ensures that its title is prominent in the composition. This portrait is not of the maternal body but rather the maternal mind. It is a topical view, a loving but dispassionate representation of a mother not as a nurturer but as a wise woman.

The work is effective due to the power of Cassatt’s stylistic acumen. The palette is sober and reduced, predominantly comprising blacks, whites and grays, the colours of the printed word itself. Her mother’s black-framed pince-nez, an instrument of vision, sits prominently beneath her black hair, and both reiterate the black print of the paper. Cassatt acknowledges that sight is the sense most closely aligned with thought and that intellect is associated with masculine power, and she visually challenges these assumptions here.

Mrs. Robert S. Cassatt was painted a decade later when Cassatt’s mother was elderly and ill, but the portrait still conveys a powerful presence. One is led to the mother’s intelligent face by the visual elements around it. Her figure is recognized as solid by its arrangement and the traditional thinker pose she assumes.

4.12

| Femininity and the Gaze

In the Loge expresses Cassatt’s interest in the complex subject of the gendered gaze. The black-clad young woman sits assertively in her loge at the opera. Her figure looms large in the composition, conveying personal energy as she directs her opera glasses across the picture plane. She is focused on a spot that is not the stage and is also not visually accessible to the viewer. From within the painting, another figure fixes his gaze upon her, looking outward, mirroring the spectator, while we look inward at them both. Within this juxtaposition of viewing, it is the woman who is actively looking and who is prioritized.

Despite the social setting, a public venue where women were exposed and expected to be observed, this woman does not read as vulnerable. Her sombre dress, directed gaze, and eyes masked by her opera glasses all foil her objectification. The fact that she is actively ‘elsewhere’ renders her safe from voyeurism and the flaneur. This male figure flocked to social spaces of spectatorship where fashionable young socialites were on ready display.

When Charles Baudelaire wrote “The Painter of Modern Life,” published in Le Figaro in 1863, the figure of the flaneur resonated with artists. “To be away from home and yet feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world and yet remain hidden from the world-such are a few of the slightest pleasures of those independent passionate impartial natures which the tongue can but clumsily define. The spectator is a prince and everywhere rejoices in his incognito. The lover of life makes the whole world his family.”

The flaneur was, by social circumstance, always male, existing as he did in the public realm. He moved about incognito, with the freedom to look, to watch. Women were positioned as the objects of the flaneur’s gaze.

Baudelaire wrote:

Woman is for the artist in general…far more than just the female of man. Rather she is divinity, a star…a glittering conglomeration of all the graces of nature, condensed into a single being; an object of keenest admiration and curiosity that the picture of life can offer to its contemplator. She is an idol, stupid perhaps but dazzling and bewitching…Everything that adorns woman that serves to show off her beauty is part of herself… No doubt woman is sometimes a light, a glance, an invitation to happiness, sometimes she is just a word.

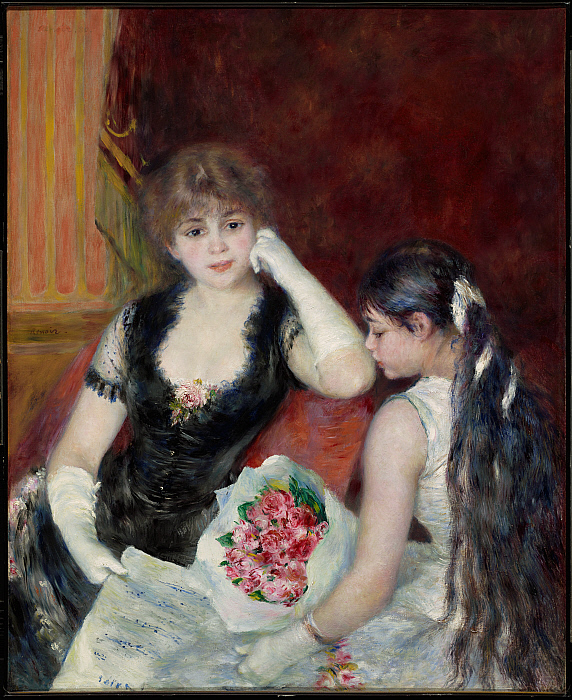

Renoir’s painting of young ladies at the opera, A Box at the Theater (At the Concert), approaches the female subject entirely as decor. It is among several works that explore spectators at theatres or concerts—the subject is all about seeing and being seen. Even though specific individuals sat for the painting, Renoir rendered the figures anonymous before completion, underscoring their role as pretty, pliable objects.

In contrast, the two young women in Cassatt’s The Loge appear posed, their postures stiff and constrained. One woman carefully grasps a pretty bouquet while the other shelters behind a large fan. They convey a mix of shyness and discomfort, uneasy on public display, being shown off, as it were.

While settings such as the opera were mostly spaces of practiced social ritual where femininity was part of the spectacle, they could also, for some women, serve as sites of intellectual and creative production.

4.13

| Reimagining Motherhood

Although Cassatt herself was childless, her images of mothers, children, and mothers with their children are considered among her finest works.

Cassatt sought to represent the “natural mother,” the timeless madonna of the Renaissance made contemporary. A secular madonna, but accessible.

There is no universal way of representing motherhood. Historical, social, and political conditions and stylistic conventions influence an artist’s interpretation of the mother image. Within the same era, images of mothers and children can vary dramatically.

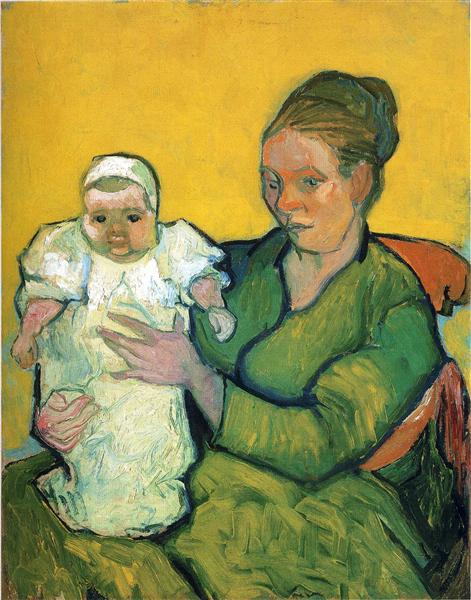

Here is the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s description of Van Gogh’s Mother Roulin with her Baby:

This vigorously painted portrait of Augustine Roulin and her infant daughter, Marcelle, is one of Van Gogh’s many evocative renderings of the Roulin family, undertaken some six months after the artist relocated from Paris to Arles. Van Gogh painted the entire family of the local postman Joseph Roulin. Here, the chubbycheeked infant is the focus of the enterprise. Her heightened expression in thickly painted brushwork suggests that the baby may have posed for van Gogh, swaddled in her mother’s embrace. Augustine Roulin, by contrast, is an abbreviated presence.

compared with the Cleveland Museum of Art’s description of William Bouguereau’s Rest:

One of the most celebrated academic painters of his time, Bouguereau underscores the moral virtues of the Italian peasants in this painting by depicting the dome of St. Peter’s in the distance. The idealized figures and their triangular grouping recall the Holy Family paintings by Renaissance master Raphael 400 years earlier.

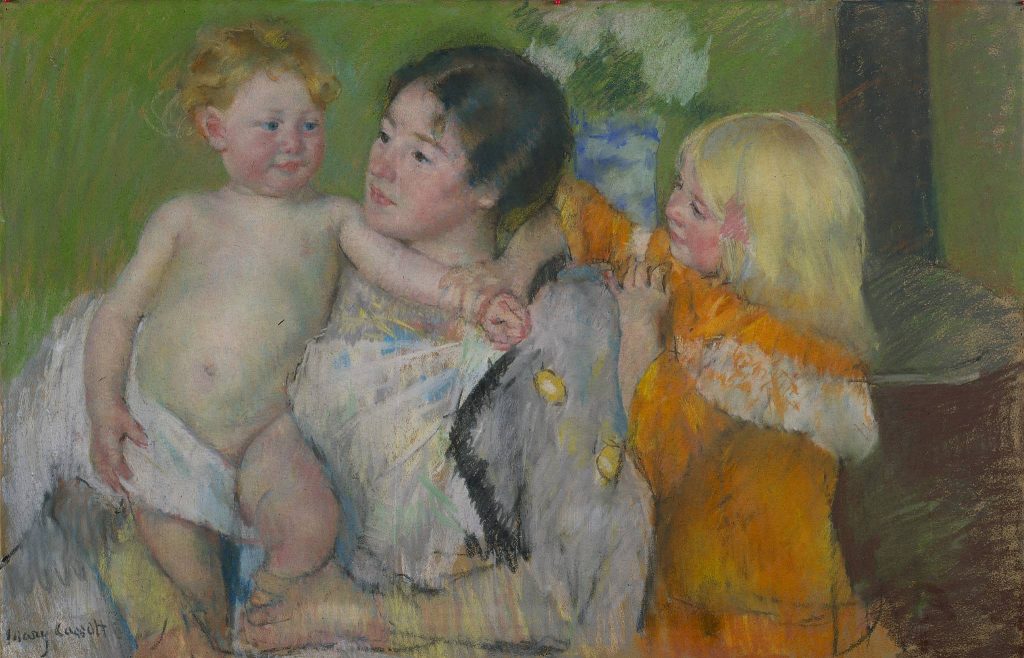

Cassatt’s After the Bath speaks openly of the fleshy delights of motherhood. Even when Cassatt confronted the more conventional aspects of motherhood, the daily rituals of bathing and clothing, she eschewed the sentimental to portray mothers and babies that reflected the actuality of women in her entourage and among the bourgeoisie.

Norma Broude asks in “Mary Cassatt: Modern Woman or the Cult of True Womanhood?” (Woman’s Art Journal 21, no.1 (Autumn 2000 – Winter 2001): 36-43):

Why the repeated images of mothers and children from an artist who was not a mother and who in her own life was reported to have taken note of children only insofar as they could serve her as models? To answer this complicated question, we must get beyond the usual cant that has been promoted since the 19th century, the myth that these happy mothers and beautiful children are natural expressions of Cassatt’s femininity and therefore more truthful as images of the mother-child bond than any previously painted. And we must consider instead the specific social and market contexts that framed Cassatt’s choices and the reception of her work.

On one level, in the surprisingly seductive and even Michelangelesque babies sometimes portrayed by Cassatt in their mothers’ arms, for example, we may be seeing, in a guarded and limited form, this artist’s only respectable access to the unclad figure and to the high art tradition of the nude. But in more far-reaching terms, I would reiterate that Cassatt was a self-conscious and skillful player in a game of professionalism and identity still constructed to exclude women. And in light of what we know about the network of discourses-philosophical, moral, medical, and aesthetic-that defined the female creative subject, the woman artist in the 19th century, Cassatt’s choices are really not surprising. In that context, we may readily see how the subject of mothers and children-at first apparently resisted, then later embraced by this artist-would have provided for Cassatt one of the few, narrow gaps of possibility within which she, as an ambitious woman artist of the upper classes, could fully grasp and define for herself a socially acceptable professional status and identity. And the success of her strategy-as strategy I believe it was-is easily measured by the sudden outpouring of articles and in particular by the proliferation of reproductions of Cassatt’s works that began to appear in popular journals both in France and the United States from the turn of the century onward. These included such diverse publications as Scribner’s Magazine (1896), Brush and Pencil (1900), L’art decoratif (1902), Les modes (1904), La Revue de l’art ancien et moderne (1908), Harper’s Bazaar (1911), Les Arts (1912), Arts and Decoration (1915), Town and Country (1916), and many others. If Cassatt’s presumably natural and spontaneous images of mothers embraced by children who hang affectionately upon their necks remind us not only of Renaissance madonnas but also of the happy mothers of 18th-century bourgeois art, that, too, is not accidental.

The oeuvres of many late-18th-century painters, from Sir Joshua Reynolds to Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, graphically portray the joys and rewards of family life and particularly of motherhood, often depicting physical intimacy between mother and child or showing us the adoration of a secular infant. And as we now know, such images were part of a wider, late-18th-century program of moral edification and reform that encouraged women to assume and indeed to wallow in the joys of maternal responsibility, at a time when such behavior had not, in fact, been the cultural norm. A century later, during the 1880s and 1890s, when Cassatt began to devote herself so successfully to the production of similar images, it may have been, in large measure, because a similar kind of social problem existed in France, and visual representation was once again being called upon to play an important, propagandistic role in helping to redefine and reshape the social order. Cassatt’s images of happy and fulfilled mothers, surrounded by children who are the personifications of goodness and innocence, these pictures that deify motherhood and its joys, were painted in an era of great, even hysterical public concern over declining birthrates in France.

…

In this time of change, as middle-class women were gradually gaining legal access to education and even, after 1884, divorce, debates over the femme nouvelle suddenly flooded the Parisian press; and the “new woman’s” desire for independence and education over traditional values of marriage and family was not only seen as a threat to the structure of the family but was also being publicly blamed for the declining birthrate. Images proliferated during this period, in the popular press and magazines as well as in high art, equating motherhood with patriotism and promoting women’s traditional role in the home as the anchor of bourgeois domesticity. The good of family and country was thus used as a persuasive argument in efforts to control and limit women’s access to higher education and the public sphere.

France’s political upheavals of the early nineteenth century had visibly changed Parisian demographics. Social transitions, including the influx of rural migrants seeking work in the newly industrialized city, coincided with extreme poverty and unemployment. A standard solution to the problem of unwanted pregnancies for poor working-class women was legally abandoning their children to state-run hospices.

In 1902, the magazine L’Assiette au Beurre published a disturbing cover that accompanied its story on unwed mothers. The horrors of infanticide and infant abandonment, despite the development of social welfare programs designed to prevent it, were an ongoing class issue.

In addition, a concern with the social order in nineteenth-century France led to the tabling of laws during the Second Republic, which deliberately ostracized the homeless, separating them from the rest of society. Brussels-born Alfred Stevens illustrated the activities of the “chasseurs à pied” as they escorted a homeless family, a mother and her two children to prison in The Hunters of Vincennes, which was exhibited in the 1855 Exposition Universelle under the title “Ce qu’on appelle le vagabondage.” Working in a social realist style, Stevens rendered the scene in stark terms capturing the overall sense of alienation. The winter’s gloom, the monochromatic dark wall against the white snow, the lack of horizon and the two posters, one advertising land for sale, the other an invitation to a ball, evoke the contrasting realities of life in Paris at mid-century.

Stevens approached the theme of poverty as a political problem. The law at the time stated that people with no profession, no residence or no means of subsistence should be imprisoned for three to six months. Without a husband to support her, the wretched mother walks obediently with the police officers. The painting reflects the artist’s sympathy for the mother’s destitution and questions the unfair imprisonment that will not help this desperate family. While the artist depicted the idea of compassion (represented by the wealthy woman attempting to intervene with the soldiers and the lame worker with a downcast expression), he condemns the reality of State repression. In no uncertain terms, The Hunters of Vincennes criticizes the persecution by government of the weakest in Society.

Emperor Napoleon II, shocked that French soldiers were depicted performing such a base task, demanded, unsuccessfully, that the work be removed from the exhibition. Instead, Stevens was awarded a second-class medal.

4.14

| New Perspectives

The Child’s Bath and other similar works by Cassatt recall Degas’s women bathers, particularly in the bold form, tilted perspective, and the subdued, psychological remove they convey. The flat, shallow surface, which compels our eye up and across the canvas rather than into it, is equally common to both. However, the use of multiple patterns and sophisticated colours in the formal construction is particularly Cassatt’s, a design aesthetic that she daringly and dynamically articulates.

One sees it here in the play of the wallpaper pattern against the background bureau, the dissimilarity of the juxtaposed rugs, and the mauve, olive, and white stripes of the dress that are upturned and repeated in the patterning of the fingers, all of which are set into play by the exaggerated scale of the pitcher in the foreground leading the eye up and onto the pictorial surface.

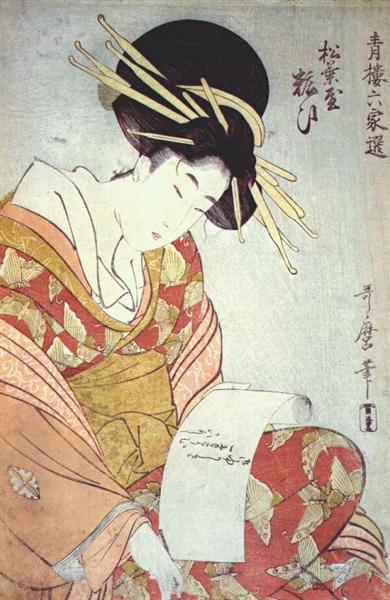

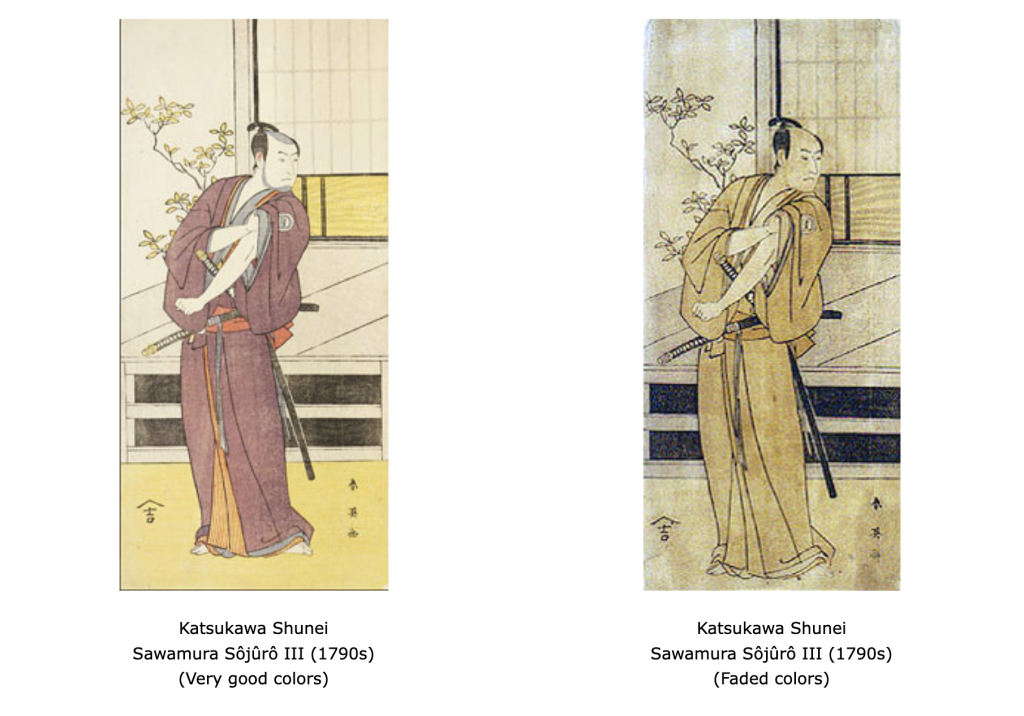

Like many European artists of her era, Mary Cassatt collected Japanese prints. The flat colours and patterning, the fluidity of her lines, and the simplification of the volumes attest to the fact that she was looking at and stimulated by Japanese artists, particularly Kitagawa Utamaro’s mother and child woodcuts.

Japanese artists such as Utamaro were superbly adept at mediating and transforming scenes of intimate life, which Western art tended to sentimentalize into works of formal rigour and emotional subtlety. This strategy attracted Cassatt and is evident in many of her prints.

4.15

| Picturing Children

Cassatt’s ability to depict children fully absorbed in their worlds is evident in works such as Little Girl in a Blue Armchair. These paintings convey the child’s experience from an emotionally truthful perspective. The intense, fresh palette she employs in these images augments the spirit of her subjects, from a squirming baby to the young girl sprawled out in a big blue armchair.

The little girl is pictured not so much resting as occupying a space between doing and not doing. Her pretty dress and the lush furnishings indicate her bourgeois status, but she displays neither the attitude nor the proprieties of her class; she is just herself, a girl on her own with her dog. As a model, her appeal to Cassatt was precisely due to the absence of any social mannerisms. She captures the irritation of the dressed-up girl, who is fatigued and fidgety at once. The billowing dress is rumpled; the stiff pose is now casual, and her red lips are turned down in disdain for sitting for her portrait. It is also possible to read a certain amount of pubescent sexuality in her sprawling pose.

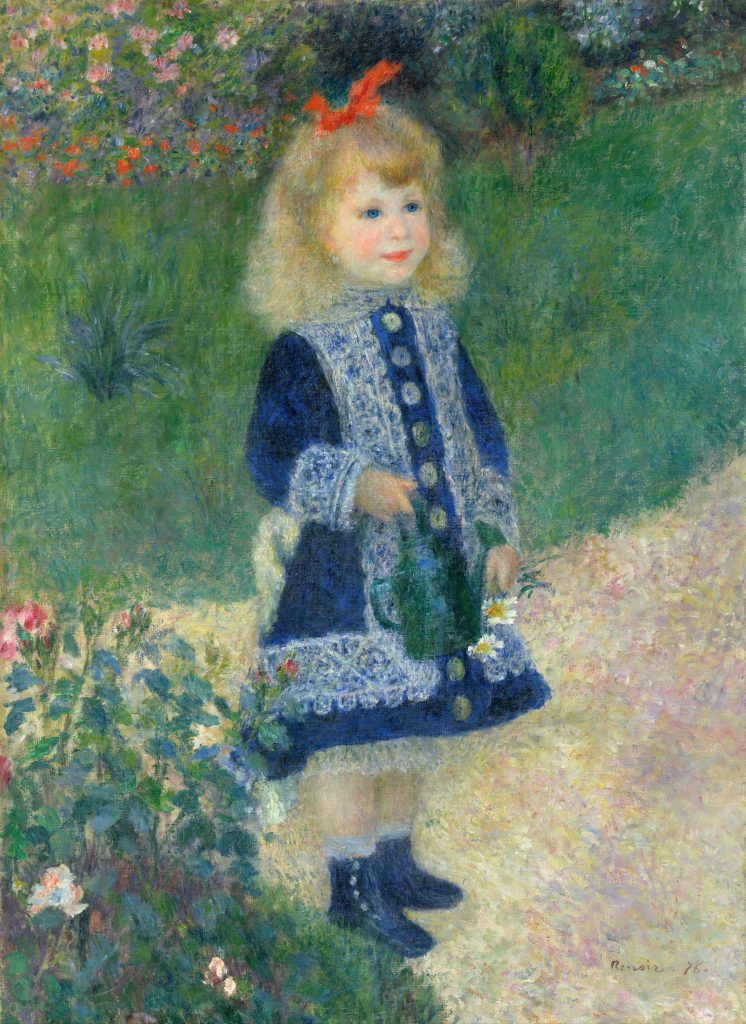

The young girls’ restive attitude is in marked contrast to the conventional and angelic manner of Renoir’s children. Cassatt presents an independent identity for girlhood by actively dismantling the traditional representations of model little girls found, for example, in Renoir’s work.

In Renoir’s A Girl with a Watering Can, the child looks like a doll, her body blending in with the decorative patterning of the canvas. Her face is intricately detailed, sharing the wide-open eyes, fluffy golden hair, extra red lips, pale skin, and lightly rouged cheeks that were common to dolls at the time. The child’s stiff stance and delicate dress are similarly doll-like, conveying an impression of limited movement and objectified display.

Rather than running, playing, laughing, or crying, the little girl poses; her watering can is a static prop like the private garden around her. Her gaze is blank, her prettiness idealized as if she is part of an advertisement. She is commodified, a product of bourgeois culture, signifying wealth and the domestic family.

In many ways, Renoir’s images are an extension of the doll market itself, they mirror the dolls, and in making them real, they themselves appear mechanized.

During the 18th century, dolls were hand-crafted figures made of wood or stuffed leather, their features painted to resemble a generic adult woman. The bisque porcelain doll was an invention of Pierre Francois Jumeau in the 1840s. By the 1870s, France’s pre-eminent doll-making firm had increased production from 10,000 in 1879 to 300,000 in 1889.

Because most doll owners were girls, most of the mass-produced dolls were female and looked bourgeois, with delicate bisque or porcelain faces, eyes of glass, and intricately fashioned mohair or human hair wigs. The famous doll industry was propagating the ideal of female perfection. At the same time, images of children proliferated, indicating increased respect for the importance of child development as part of the new and bourgeois domestic ideal.

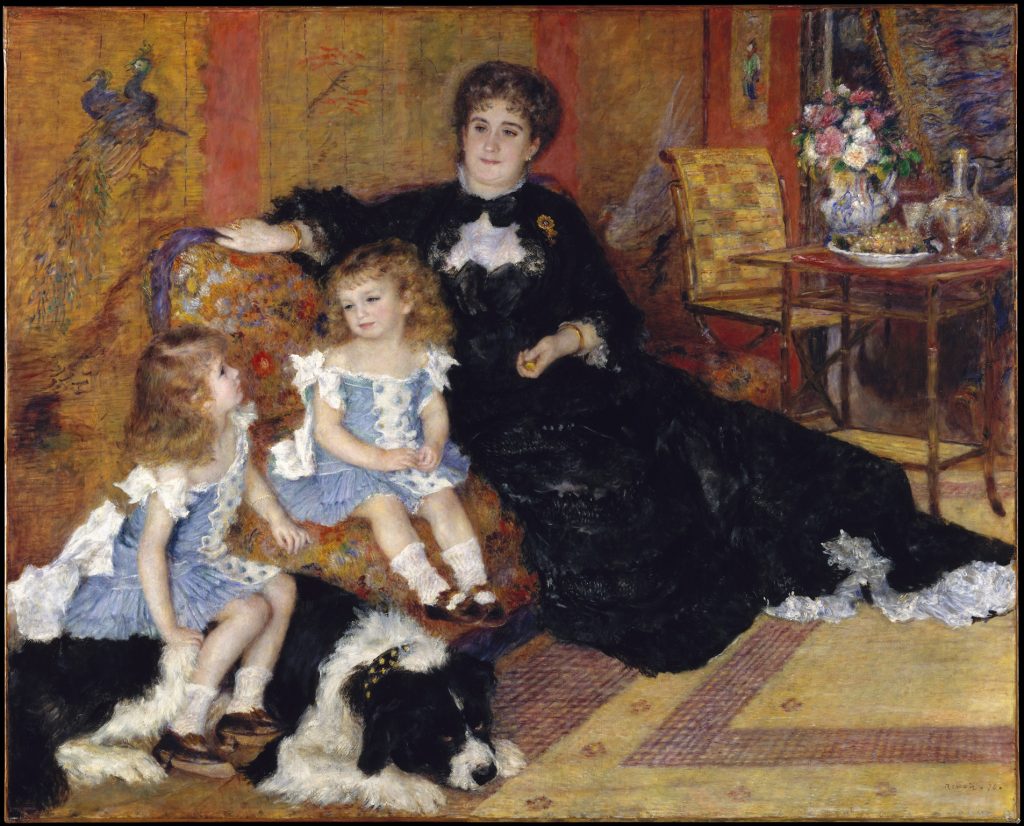

The children in Renoir’s Mme Charpentier and her Children look like commodities on a store shelf, the shiniest of many luxury ‘items’ pictured, including fashionable clothes, rugs, tableware, a Japanese screen, and even a large dog. Every ‘object’ evokes the wealth and refined taste of Mme Charpentier, a prominent organizer of Salons whose husband Georges published avant-garde literature. The children, like expensive dolls, carry an aura of special value. Their elegance, the sensuality of their surroundings, and their easy naturalness are signs of their mother’s elitist status. She and the painting as a whole signify the importance of Monsieur Charpentier in absentia.

A curious gendered component is evident in the three-year-old Paul seated beside his mother. He is dressed identically to his six-year-old sister Georgette and looks female. While boys were commonly dressed like girls until age five, Renoir’s nearly complete cross-dressing of Paul exceeds mere costume. He has given the boy’s body, face, and hair the same attributes as Jumeau’s female dolls.

Children were depicted as generically pretty. Based on a commodified doll model, Paul’s feminine appearance was the standard form of bourgeois childhood identity.

Not only can Cassatt’s Little Girl in a Blue Armchair be analyzed in comparison with Renoir, but it is also regarded as direct evidence of the strong ties of friendship between Cassatt and Degas. The two artists admired and supported one another and remained friends for forty years until Degas’s death. Degas acquired Cassatt’s work, and she promoted him to art collectors in the United States.

Kimberly Jones explains in “Mary Cassatt’s Little Girl in a Blue Armchair: Unraveling an Impressionist Puzzle” (Archives of American Art Journal 53 no. 1/2 (Spring 2015): 116-121):

Perhaps the single most important piece of evidence of that relationship is found in a letter written by Cassatt around 1903 to the dealer Ambroise Vollard. In this letter, which is in the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art, she recounts the history of her painting Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, one of a dozen works she presented in 1879 at the fourth Impressionist exhibition: “Dear Sir, I wanted to come back to your place yesterday to talk to you about the portrait of the little girl in the blue armchair. I did it in 78 or 79- it was the portrait of a child of friends of M. Degas- I had done the child in the armchair, and he found it to be good and advised me on the background, he even worked on the background-/ sent it to the American section of the Gr[and], Exposition 79 but it was refused. Since M. Degas had thought it good, I was furious, especially because he had worked on it – at the time it seemed new, and the jury consisted of three people, of which one was a pharmacist!” This extraordinary letter provides invaluable insight into the dynamic between the two artists at this critical juncture in their careers. Cassatt’s trust in Degas and her appreciation for his judgment are immediately apparent, while the evident warmth with which she recalled the incident even decades later underscores the genuine fondness and mutual respect that existed between the two. The implications of Degas’s participation in this painting are tantalizing and have led to much speculation upon the exact nature of his purported involvement. Recent technical analysis carried out by the department of painting conservation at the National Gallery of Art not only corroborates Cassatt’s account, but has helped to identify the precise location and extent of Degas’s intervention. His contribution- the introduction of a sloping wall as a means to heighten the sense of space- is relatively minor. The difference in his handling of paint is so discreet that it would easily have escaped notice were it not for the testimony of Cassatťs letter. There can no longer be any doubt that Little Girl in a Blue Armchair marks the true beginning of the vibrant artistic exchange between the two Impressionist masters.

In A Woman and a Girl Driving, Cassatt has set her figures in an open outdoor space. Her sister Lydia confidently drives a carriage while the family groom rides at the rear. Beside Lydia is Degas’s niece Odile Fevre who is portrayed as a pretty porcelain doll. Her frozen posture echoes Renoir’s doll-like kids, but in this case, it attaches to the little girl’s palpable apprehension.

A sense of containment here contradicts the freedom associated with being outdoors. The three figures form a cramped pyramid, pushed up against the picture plane, and the composition feels unnatural.

The two females seem to be on display, conscious of it and uncomfortable. This discomfort is especially discernable in the costumed artifice of the little girl. Steadying herself on the carriage rail to maintain her composure, she appears to mirror Lydia, suggesting that she is already sharing the adult’s sensitivity to being actively observed.

It has rarely been noticed how many of Cassatt’s children, babies mostly, are stark naked and sexually differentiated.

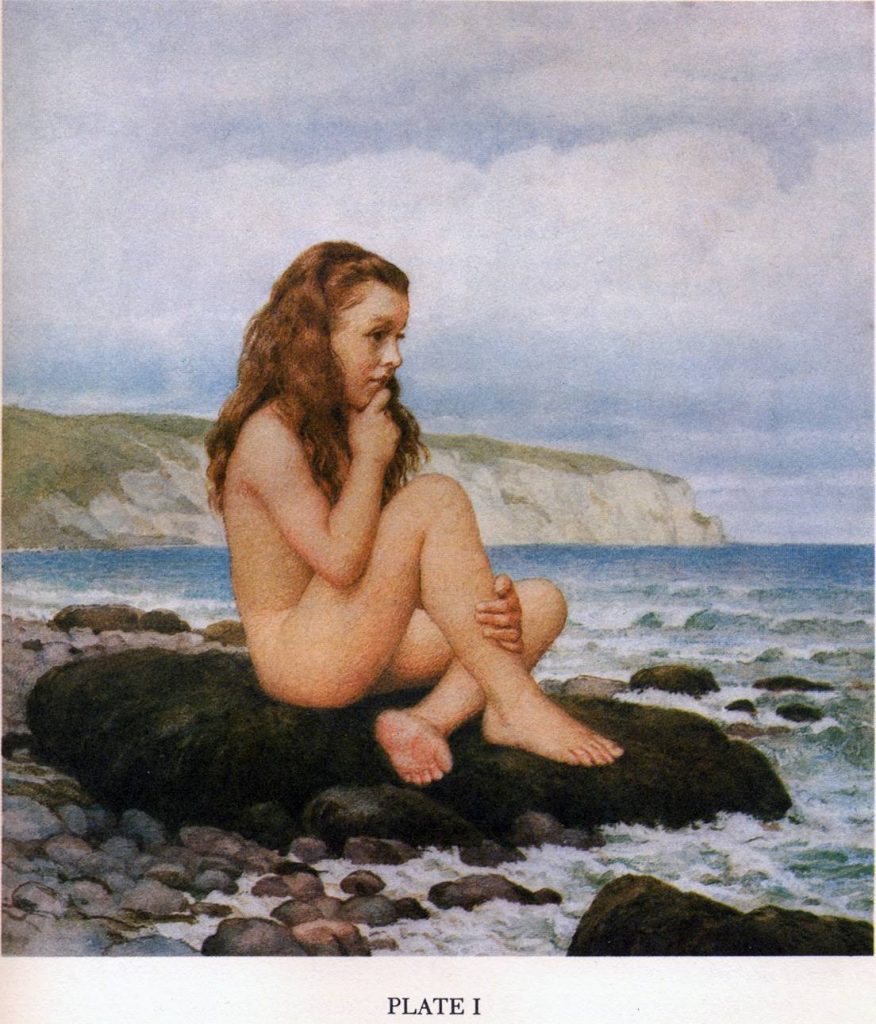

This may be partially due to the much-seen pictorial precedent of the semi-naked Christ child during the Renaissance. But the discussion may also have been avoided considering contemporary psychoanalytic theory and the potential of revealing disturbing undertones and overtones or aspects of the artist’s sexuality. During the nineteenth century, there was deep ambiguity about the naked child.

Lindsay Smith writes in “`Take back your mink’: Lewis Carroll, Child Masquerade and the Age of Consent” (Art History 16, no. 3 (September 1993): 369-85) that during the 19th century, the naked bodies of children were envisioned as simultaneously pure and desirable as exemplified in the seductively nude or nearly nude photographs of little girls by Reverend Charles Dodgson better known as Lewis Carroll.

Carroll was an English logician, mathematician, photographer, and novelist, primarily known for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass (1871). Although it may be tempting to view Carroll’s nude girls as examples of Freudian displacement, repression, and sublimation, this may not have been the case at all. Desire takes many different forms depending on time and context.

Anna Higonnet, in her book Pictures of Innocence: The History and Crisis of Ideal Childhood (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1998), traces the history of the images of childhood innocence from the eighteenth century to the late twentieth century. She asks why the photographs of contemporary artist Sally Mann’s own children are considered more than equivocal, indeed offensive, while Cassatt’s works were acceptable a century earlier. Cassatt’s child models sat for her in full undress, the same way Mann’s daughter posed for her photo. It is worth considering whether we now live in an age of almost unparalleled repressiveness and prudery where a child’s body is concerned.

4.16

| The Language of Prints

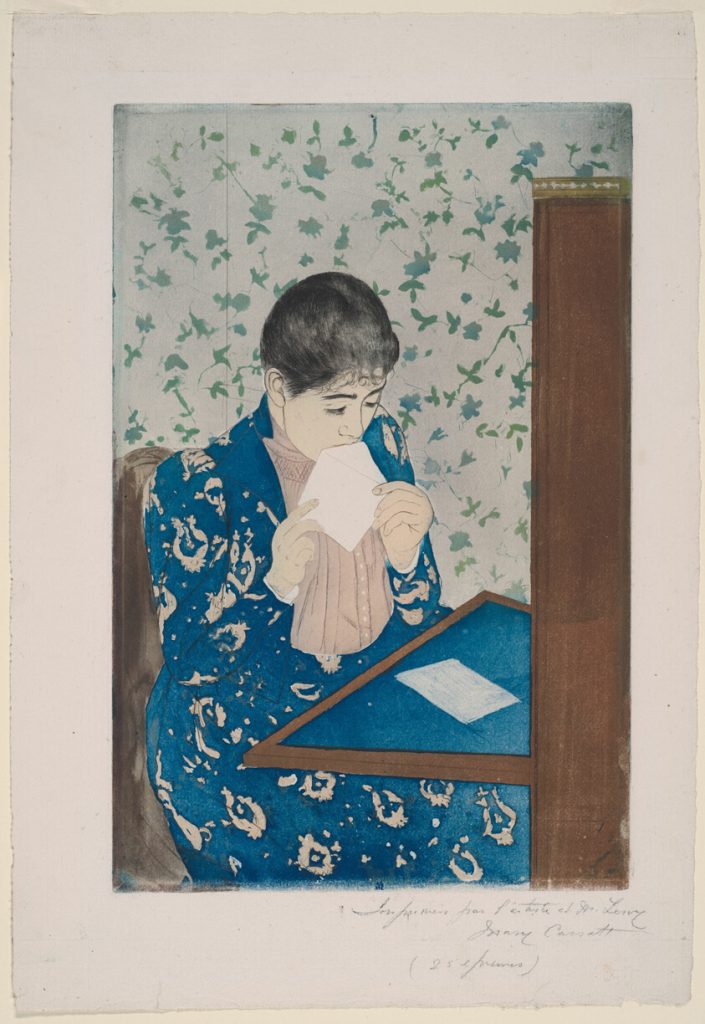

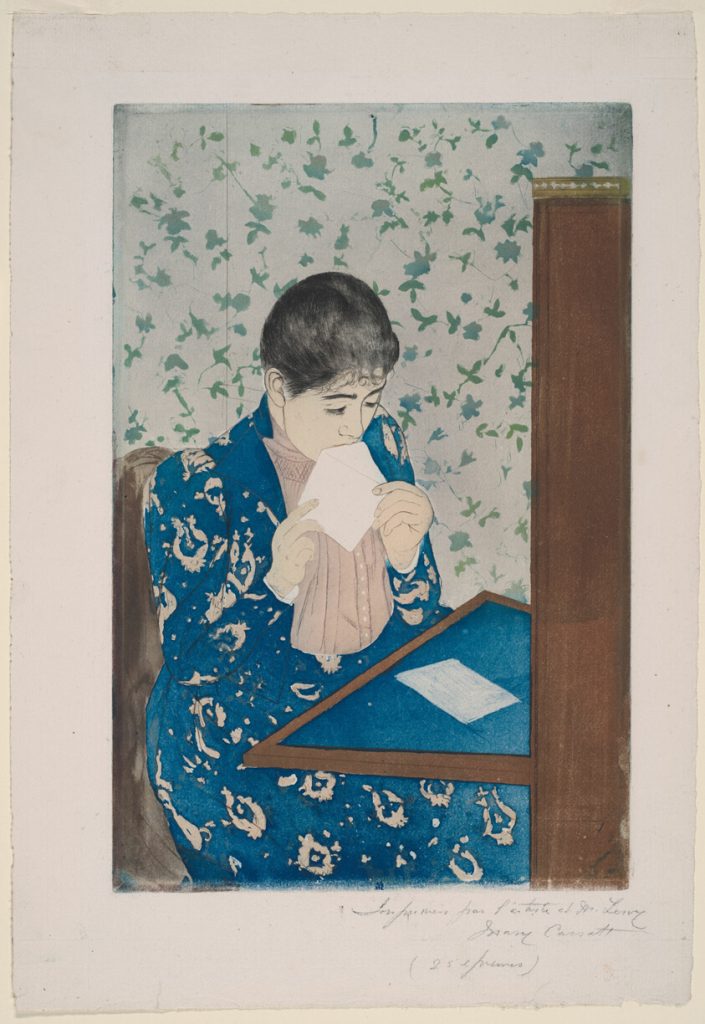

Cassatt visited an exhibition of Ukiyo-e prints at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in the Spring of 1890 and was smitten. Over the next two years she would create a set of ten coloured etchings that display her appropriation of the superb technical and formal innovations she was introduced to during her visits.

The series encapsulates events in the daily lives of refined, upper-class women: moments spent playing with their babies, private moments bathing, dressing, letter-writing, and social events. They provide a sensitive glimpse into an intimate, cosseted world, daringly filtered through Japanese prints’ stylized and elliptical language.

Cassatt interpreted the Ukiyo-e idiom in modern Western terms, a (female) language system replete with its own tropes and inventions. She could subdue the charged narrative implications of the events portrayed by activating a formal vocabulary that demanded greater attention. Cassatt transformed intimate spaces and their stories into eloquent modernist images through her minimalist approach to form and sophisticated patterning.