Chapter Ten

RELIGIOUS AND

RACIAL ANTISEMITISM &

The Jewish Artist

CONTENTS

Introduction

10.1

A Narrative of Exclusion and Emancipation

10.2

English Expressions of Myth and Faith

10.3

Imaging the Jewess: La belle juive / L’affreuse juive

10.4

Moritz Daniel Oppenheim:”The Rothschild of Painters”

10.5

10.6

Maurycy Gottlieb: Strife and Synthesis

10.7

Meijer Isaac de Haan: Controversy and Escape

10.8

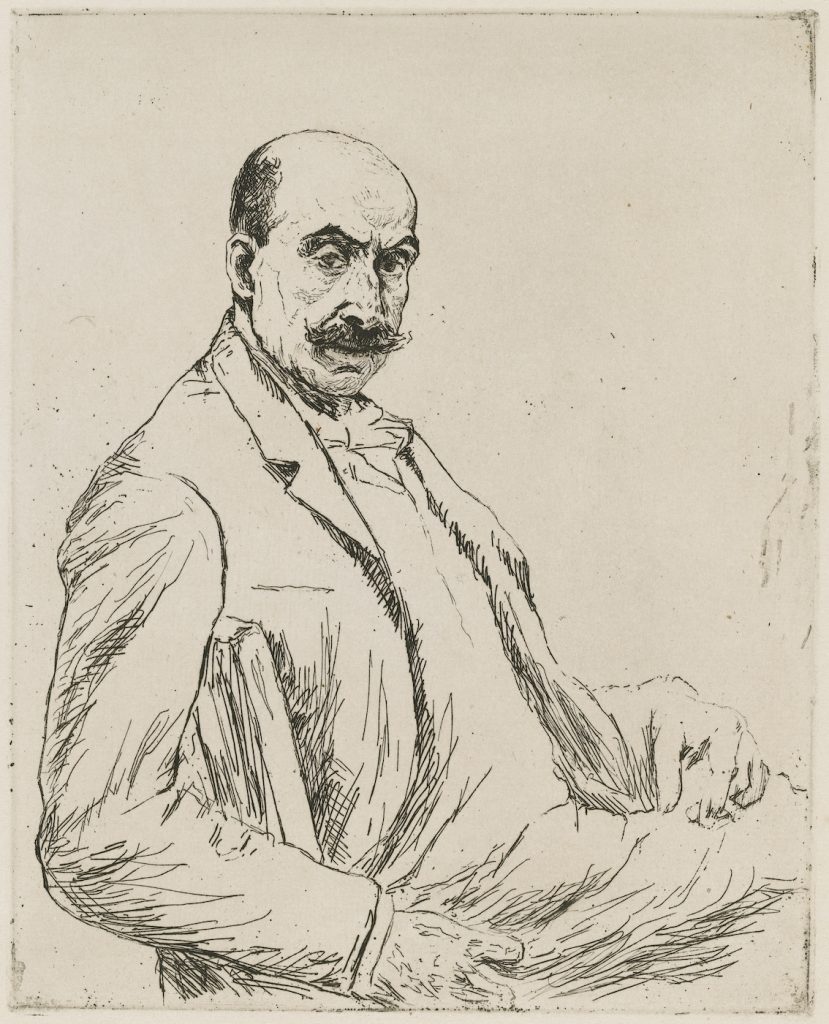

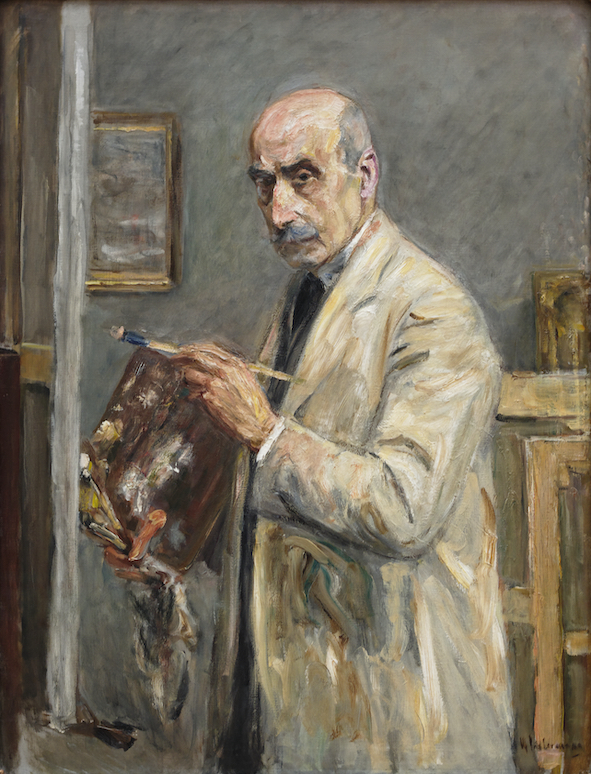

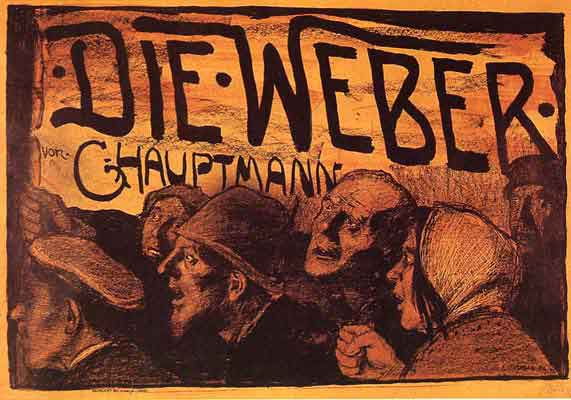

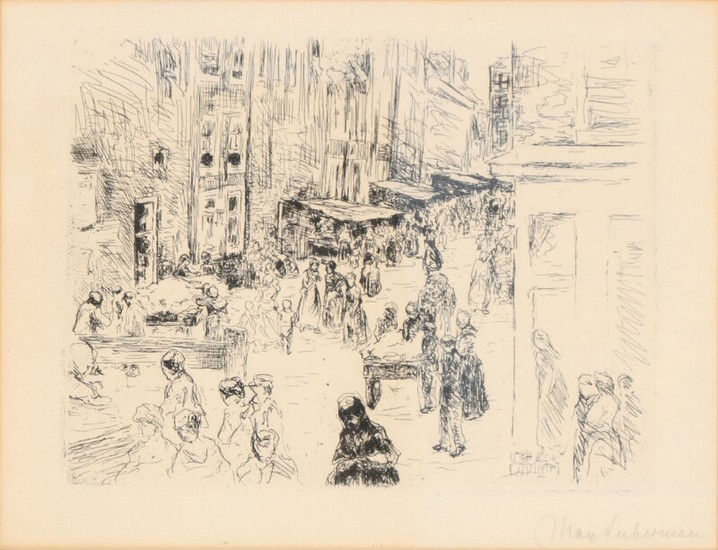

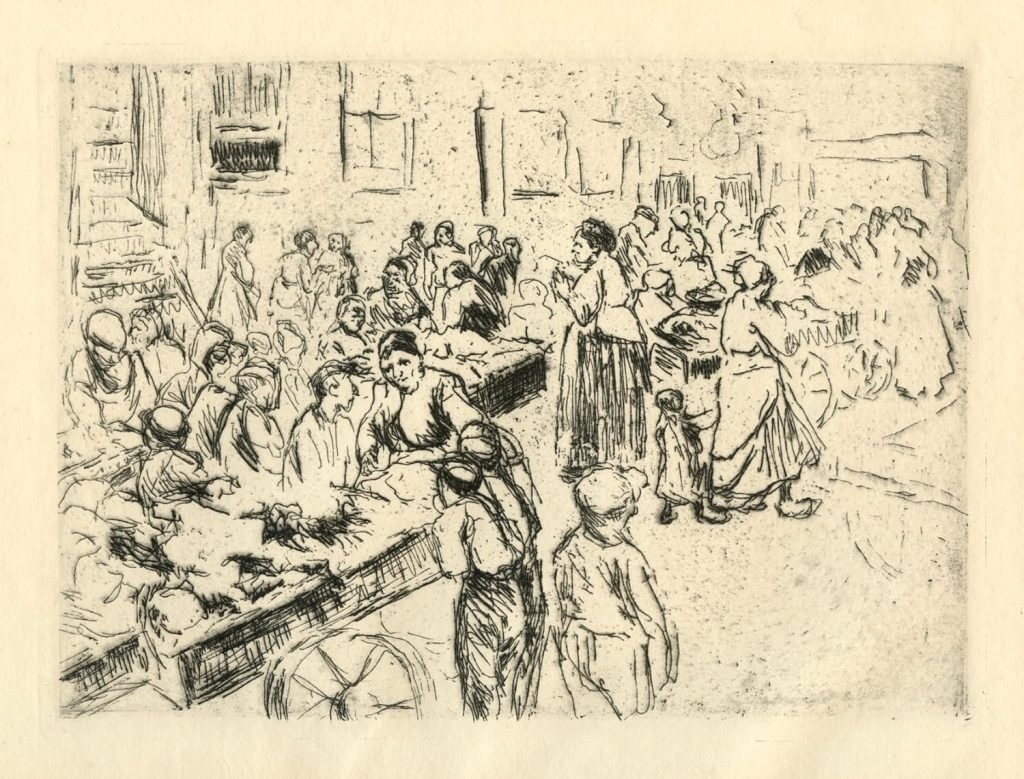

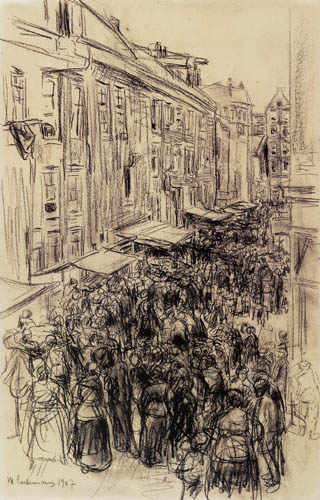

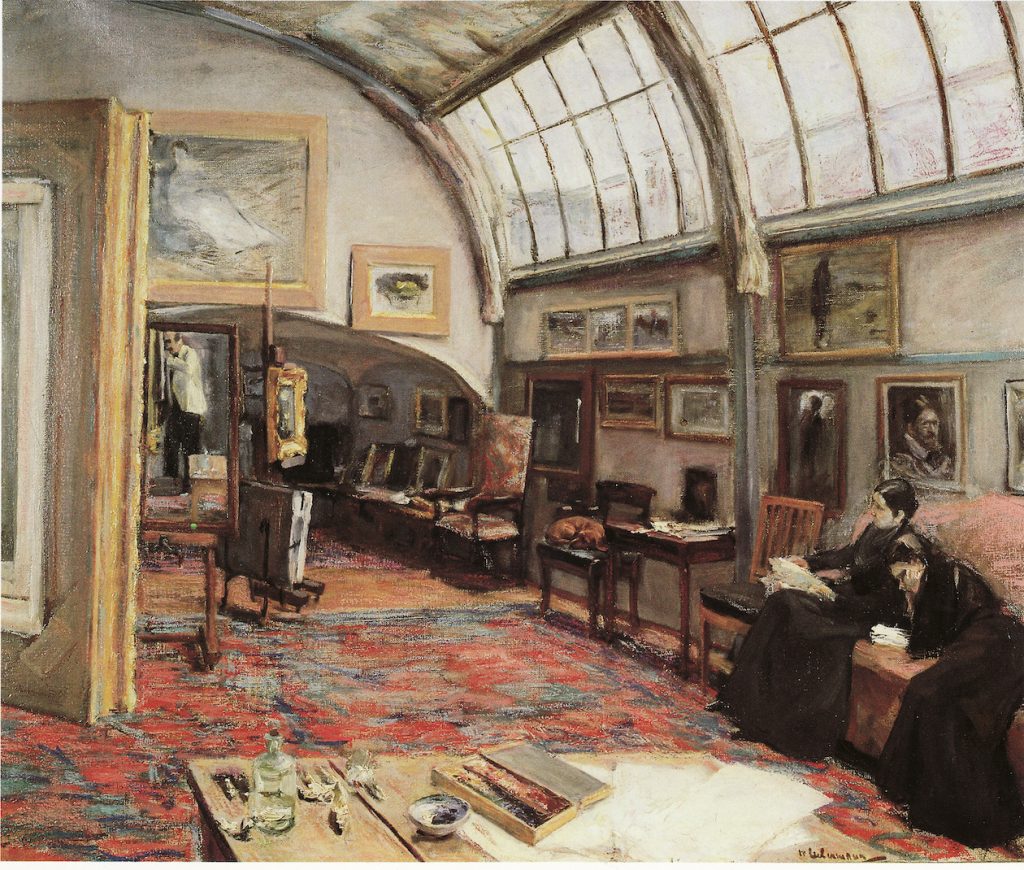

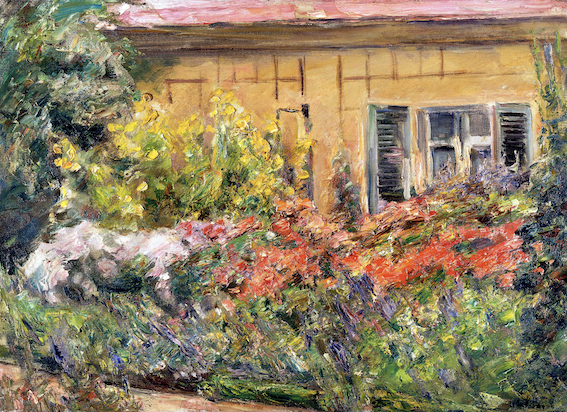

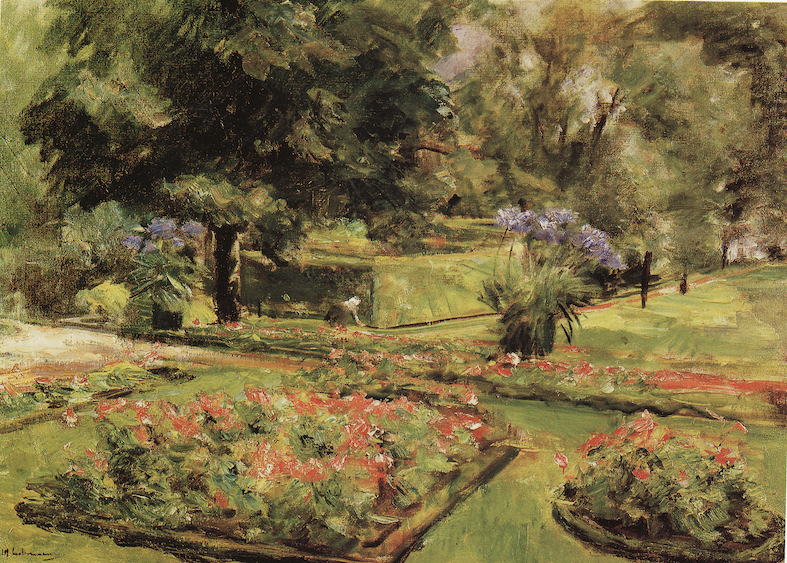

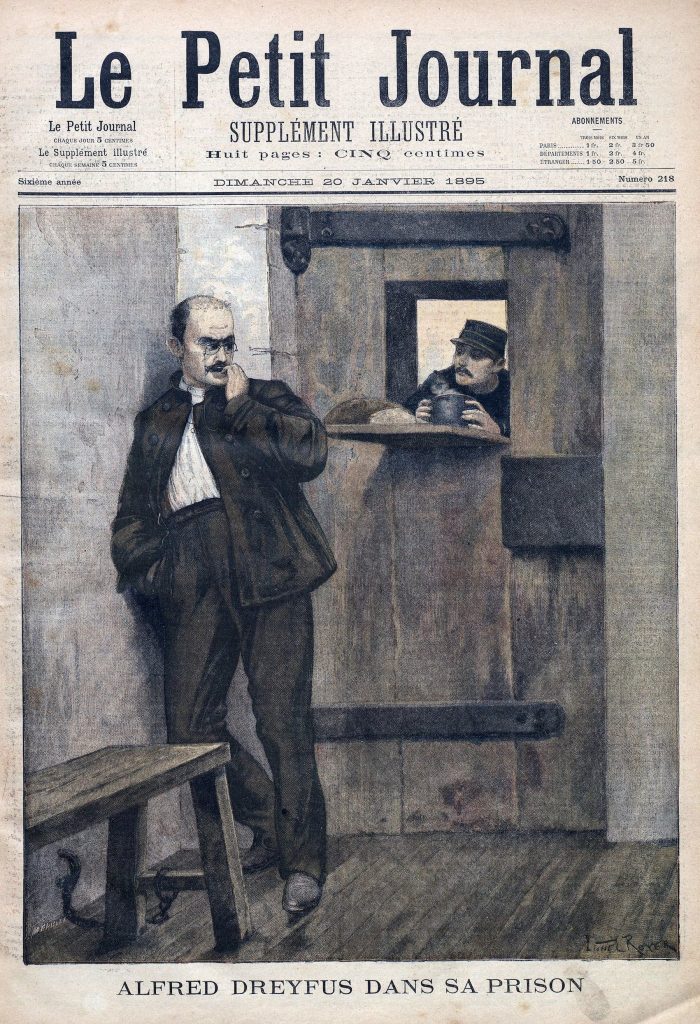

Max Liebermann: Pioneering Change

10.9

Liebermann: Subculture and Identity

10.10

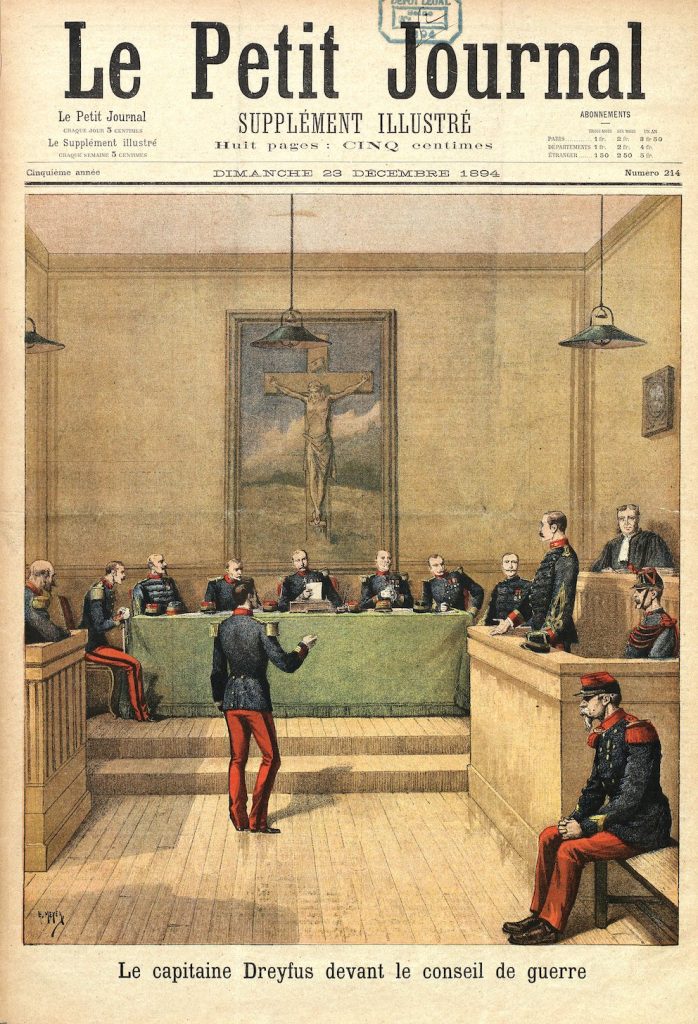

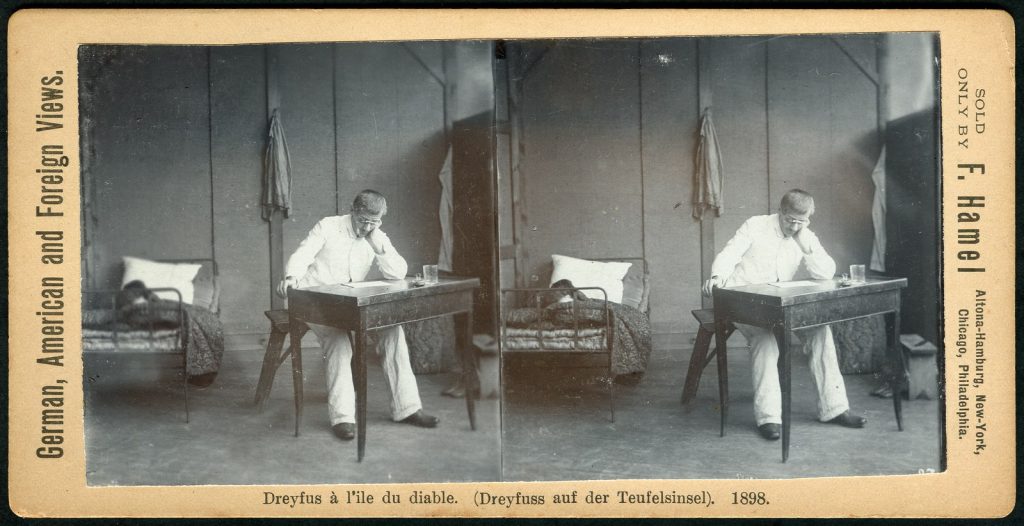

10.11

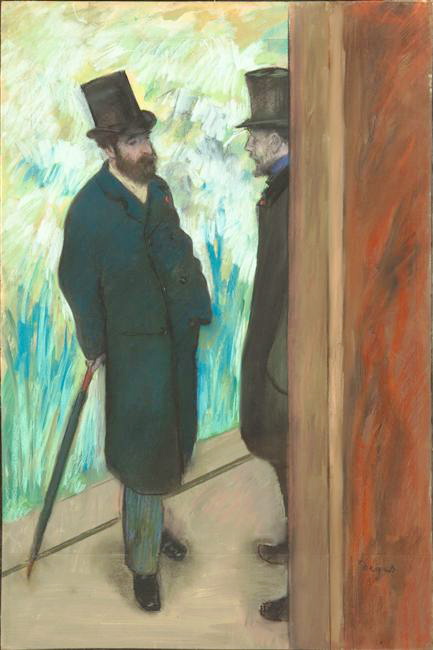

Edgar Degas: Other Impressions

10.12

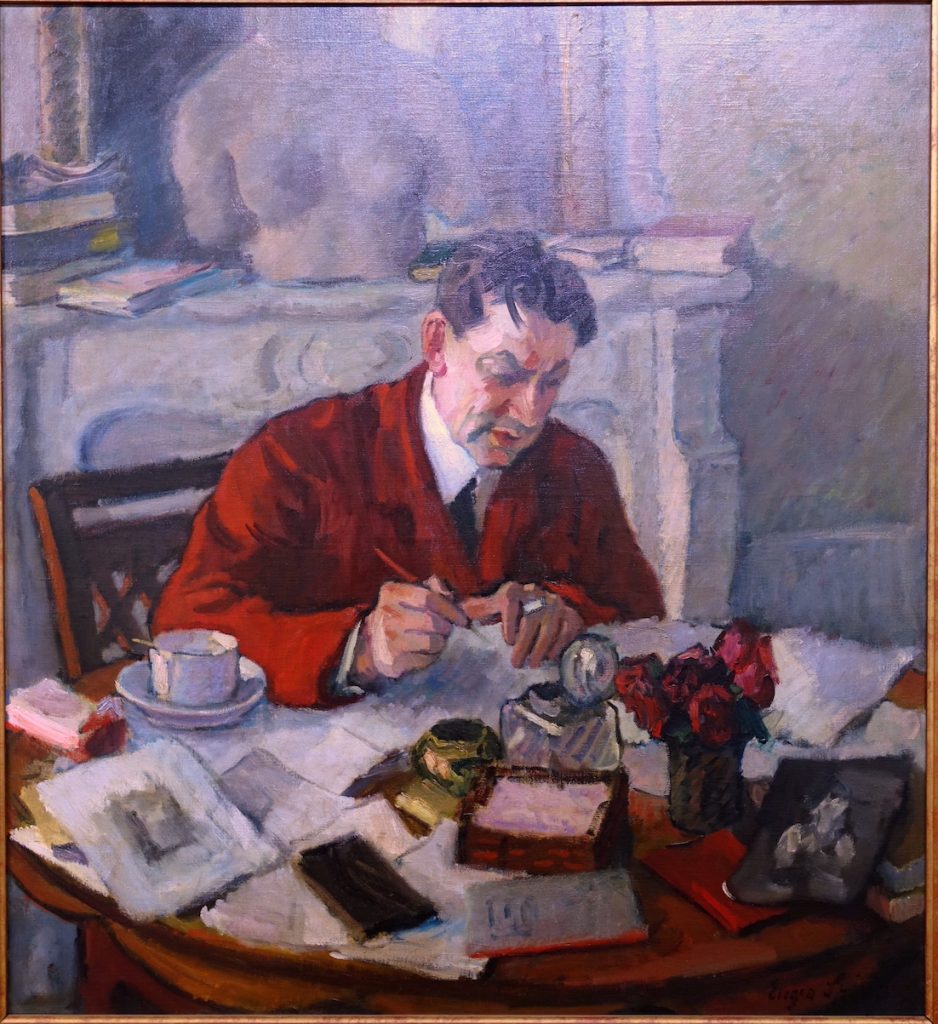

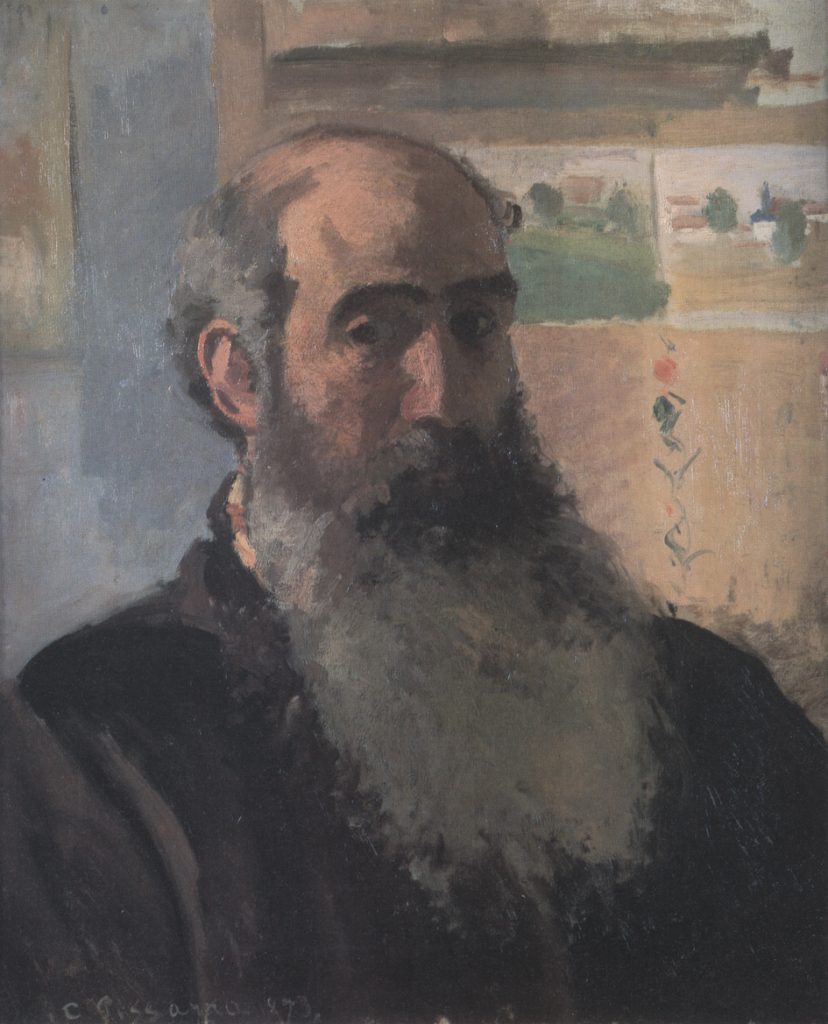

Camille Pissarro; Outsider Impressionist?

INTRODUCTION

Modernity brought radical change, turmoil, and expansion to Western Europe. Social and political events from the late 18th century forward challenged marginalized populations while providing unprecedented opportunities for economic advancement, civic equality, and cultural innovation. During the 19th century, an ideology of difference fuelled the advancement of the avant-garde. At the same time, a parallel, grimmer engagement with concepts of ‘the other’, which was largely motivated by ethnoreligious biases, permeated society and culture. For European Jews, negotiating new roles and realities in a rapidly modernizing world was further problematized by a history of racial hatred and exclusion.

This chapter will examine the impact of emancipation, assimilation, and acculturation on European Jews within the binary of a Christian/Jewish art world. It will address how Jewish artists, outsiders in every respect, engaged with visual culture in France, Germany, and Britain during the 19th century.

The oeuvre of artists like Moritz Daniel Oppenheim and Max Liebermann in Germany, Maurycy Gottlieb in Poland, Simeon Solomon in England, and Camille Pissarro in France will serve to illuminate the trajectory of Euro-Jewish artists at this pivotal moment in nascent modernity. Looking at individual narratives, the essay explores questions such as the impact of antisemitic attitudes on artistic advancement and aesthetic directions, as well as the relationship between Jewish identity and subject matter, education, and professionalization within the sociocultural context of the late nineteenth century.

The thematization of Judaic and biblical subjects by non-Jewish artists such as William Holman Hunt, William Blake, and Gustave Moreau, the propagation of stereotypes and tropes within the visual culture, and the divisive question of antisemitism in the vanguard, including among Edgar Degas and the Impressionists further expand the discussion around Jewish artists and modernism.

10.1

| A Narrative of Exclusion and Emancipation

A familiar narrative is associated with the European Jew which dates back to the Middle Ages. It is a story of persecution, displacement, resettlement, success and security, followed by renewed oppression, pogroms and exile. Until the Napoleonic era, religious and racial antisemitism restricted Jews from social entry, civil equality, land ownership, many trades, and most professions.

According to the definition of antisemitism in the YAD Vashem Holocaust Museum, Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, “Jew-hatred is not a modern phenomenon—it may be traced back to ancient times. Traditional antisemitism is based on religious discrimination against Jews by Christians.”

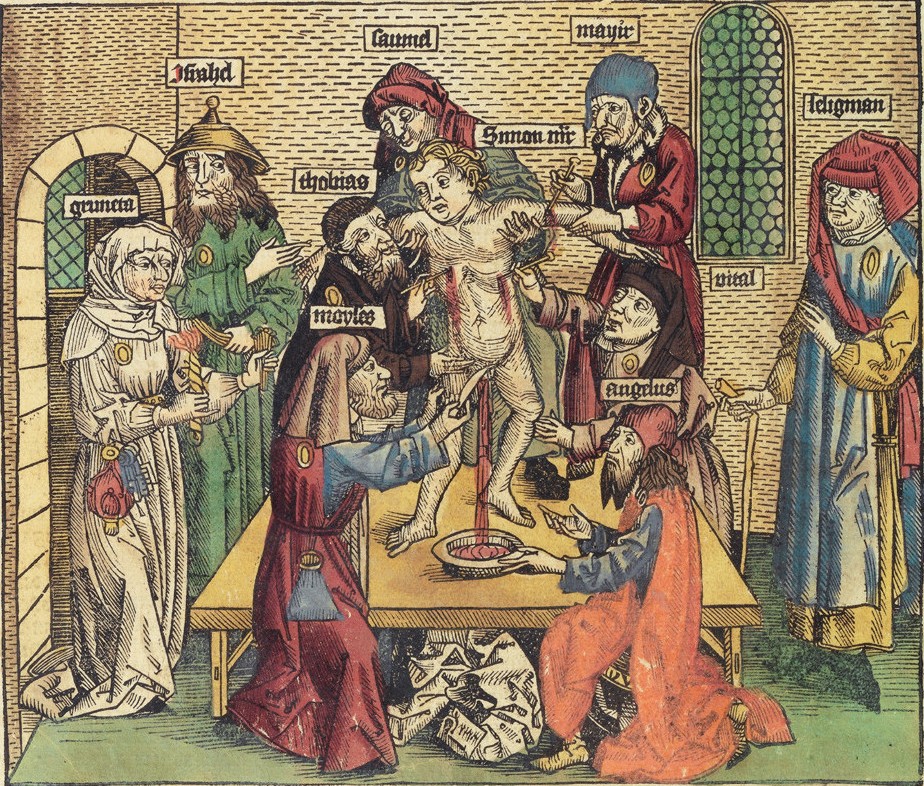

Christian doctrine was ingrained with the idea that Jews were responsible for the death of Jesus, and thus deserved to be punished (this is known as the Deicide, or Killing of God Myth). Another concept that provoked hatred of Jews amongst Christians was the Supersession Myth, claiming that Christianity had replaced Judaism, due to the Jewish People’s failure in their role as the Chosen People of God—and thus deserving punishment, specifically by the Christian world.

At varying points, Jews were accused of using the blood of Christian children as part of the Passover holiday ritual (known as the Blood Libel), as well as of malicious sacrilege against the holy communion, and of causing plagues. Initially propagated by religious fervour prejudice against Jews spread to encompass economic antisemitism.

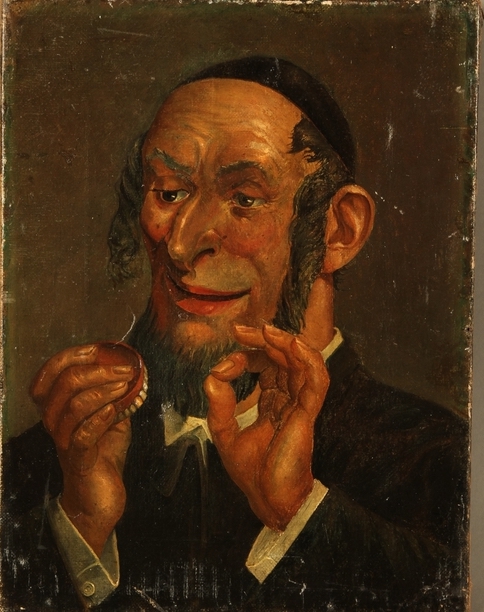

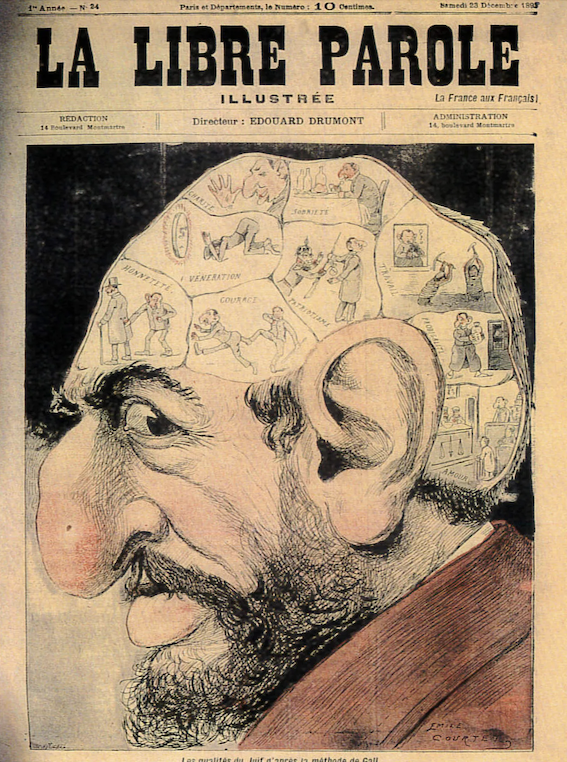

Over the centuries, stereotypes about Jews developed. Individuals were not judged on personal achievement or meritorious deeds but via racialized characterizations of greed, laziness, and depravity. During the medieval era, Christians defined themselves in relation to Jewish Otherness,’ creating polarized identities that fuelled the stereotypical representation of the Jew.

In writing about the exhibition Jews, Money, Myth, Abigail Morris, the director of the Jewish Museum in London, explains:

Artists only began to distinguish Jews from Christians from the late 11th century. Initially they can be seen with beards and pointed hats, carrying scrolls. Half a century later, they acquire distorted faces. By the 13th century they are also carrying moneybags, shown clinging to the material world and denying spirituality. As the historian Sara Lipton explains in the publication that accompanies this exhibition, the aim was to encourage Christians to avoid sin rather than hate Jews, but history tells us that this caricature has persisted and inspired murderous hatred.(https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2019/03/19/ancient-antisemitic-tropes-are-resurfacingit-is-time-to-uncover-the-myths)

The 18th century was a watershed moment in European history economically (the Industrial Revolution), culturally (the Enlightenment) and politically (the French Revolution), which sowed the seeds for significant changes in the socio-historic and economic developments of 19th-century Europe.

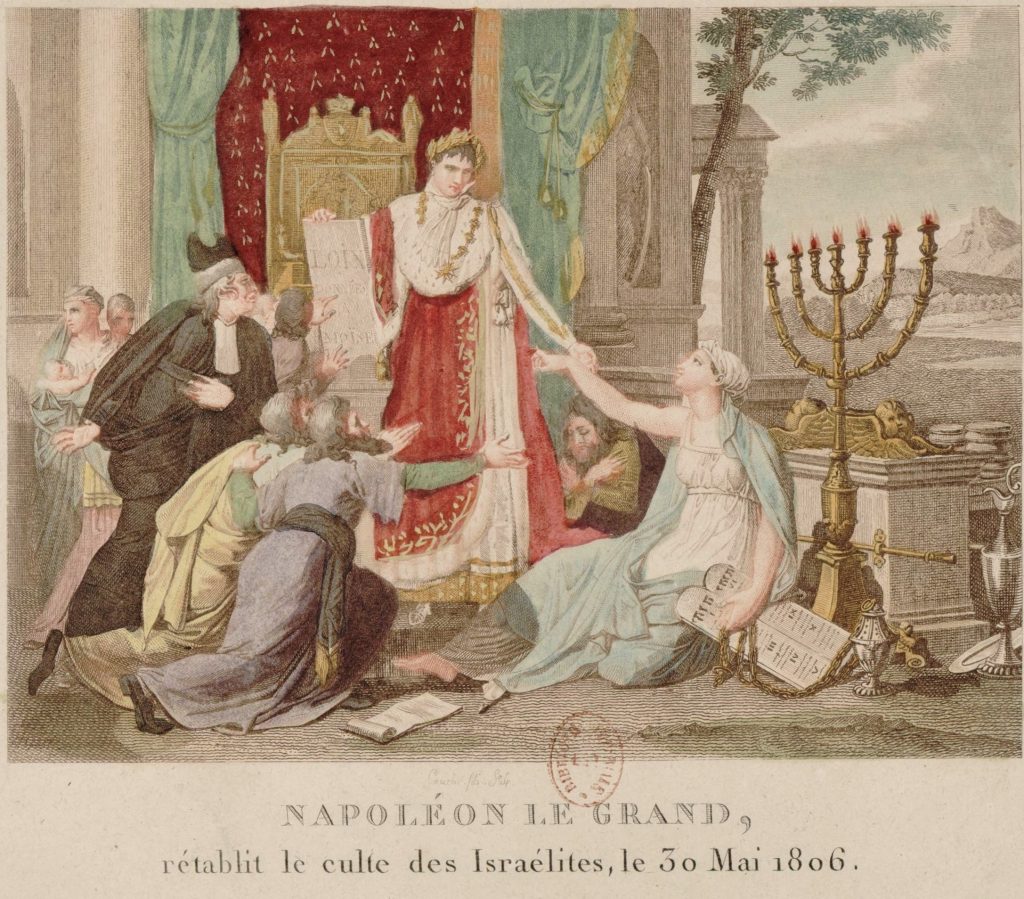

1806 marked the emancipation of the Jews in France, the first country in modern Europe to grant the approximately 40,000 Jews within its borders equal rights under the law. It set a national precedent and a new standard for Europe as a whole. Jews were emancipated in Germany, England, and other parts of Europe. Napoleon released Jews from the confinement of the shtetls (Jewish ghettos) and guaranteed them full citizens’ rights and the opportunity to transcend the negative status ascribed to them since antiquity.

With new freedom, European Jews entered a critical period of transformation with opportunities to participate and prosper in a rapidly changing society. But change also “led to a wave of secularization, assimilation and even conversion to Christianity.”(see Ben Weider, Napoleon and the Jews, https://aish.com/48945221/)

Napoleon’s enactment of the French Civic Code remains one of his most significant contributions to modern society. It provided a new legal framework with coherent laws addressing property, family affairs and individual rights. All male citizens were granted equal rights under the law, including Jews, Protestants and Freemasons. The Napoleonic Code conversely deprived women of individual rights and reduced the entitlements of illegitimate children.

Jews were emancipated as individuals of the Jewish faith but were discouraged from maintaining group identity. When the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was being debated in 1789, the question of the emancipation of the Jews was on tenuous ground. To secure its success, the Liberal advocate for the Jews Count Clermont-Tonnerre proposed a compromise declaring: “We must refuse everything to the Jews as a nation and accord everything to Jews as individuals. . . . We must refuse legal protection to the maintenance of the so-called laws of their Judaic organization; they should not be allowed to form in the state either a political body or an order. They must be citizens individually.”(quoted in Lynn Hunt, The French Revolution and Human Rights: A Brief Documentary History (Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1996), 86)

Despite emancipation, negative views of the Jew festered as fact throughout the 19th century. Thus, while modernity transformed Jewish life, offering integration and economic and social benefits, it also stimulated negative repercussions. In Christian Europe, they were still ‘the Other’. In addition, given their changing social status, Jews experienced new forms of hostility influenced partly by emerging anti-capitalist ideology.

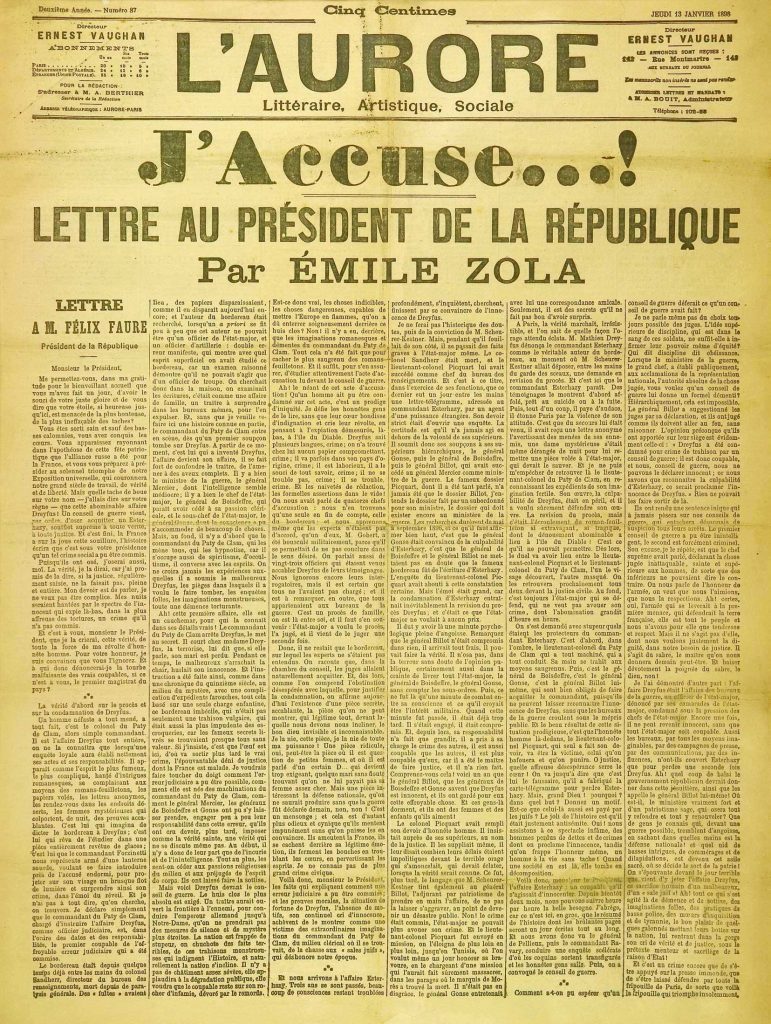

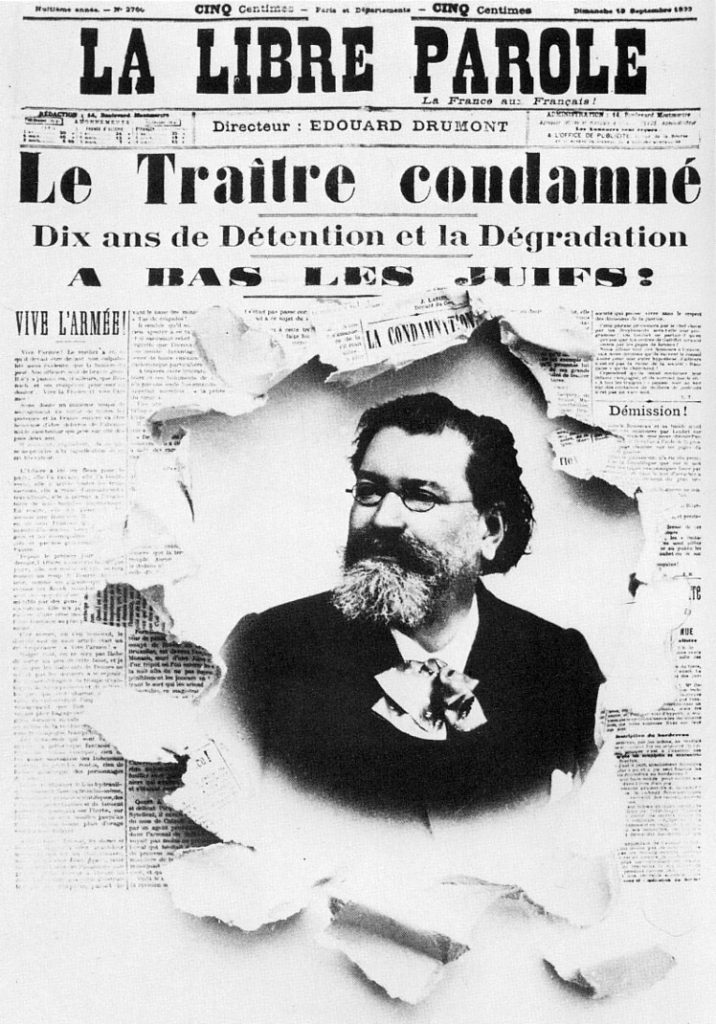

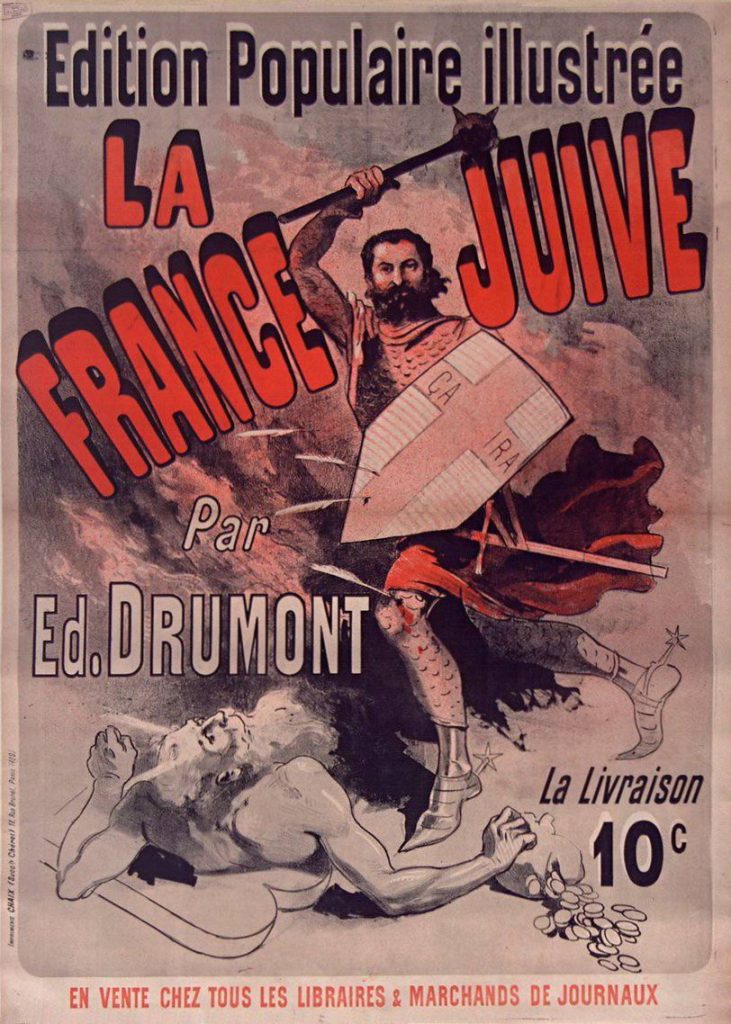

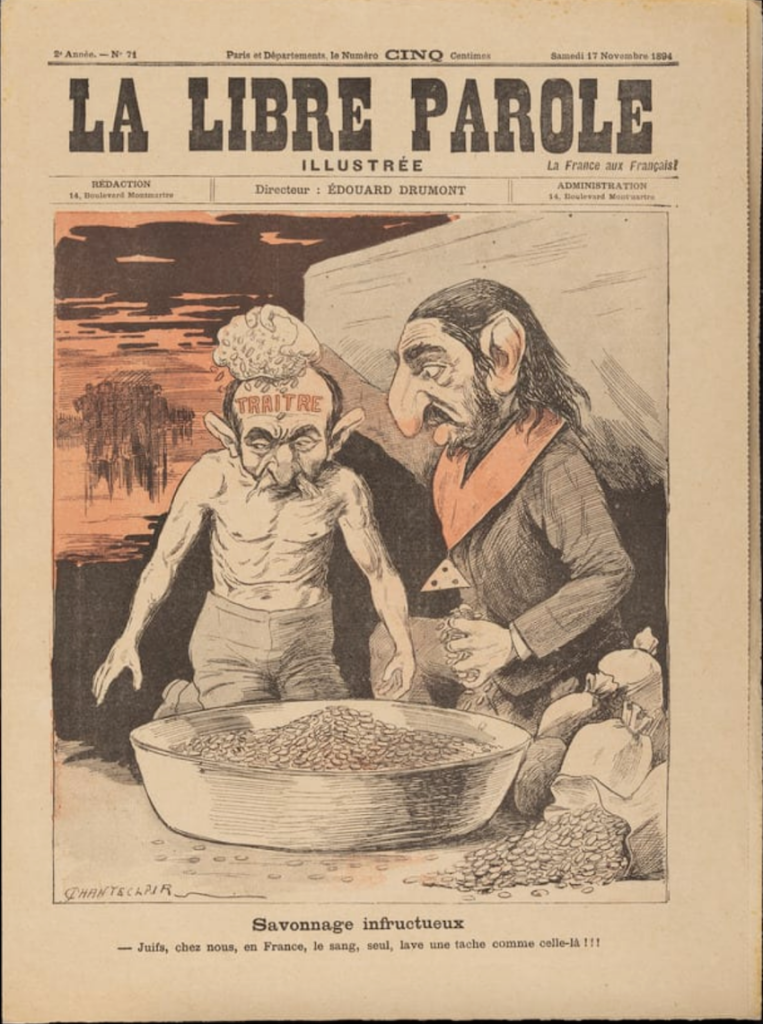

Ironically, the French Declaration of Human Rights provided new protections for freedom of speech and the press, which threatened emancipated Jews in more widely damaging ways. The principle of free speech contributed to the appearance of antisemitic publications that influenced public perception and politics. By the end of the 19th century, even Liberal parties began to adopt antisemitic platforms in France.

1.2

| English Expressions of Myth and Faith

In England, Liberals were more tolerant of Anglo-Jews. English philosemitism expressed an interest and respect for the Jewish people, but it was often attached to Christian restorationist beliefs and the notion of Jews’ return to the Holy Land. From the 17th century, restorationism centred on a doctrine of conversion of Jews to Christianity linked with the Messiah’s second coming. This belief was widespread by the mid-19th century, influencing English politics and cultural expression.

William Blake’s poetry and paintings reflect this generally ambiguous attitude toward Judaism. While he was among those artists with a primarily positive outlook toward Jews , his regard was inconsistent, ranging from mild interest in religious doctrine (particularly as antagonistic to Christianity) to virulent antisemitism as was reflected in his journals.

As Karen Shabetai points out in “The Question of Blake’s Hostility toward the Jews” (ELH 63, no. 1 (1996): 139–52):

When Blake mocks Judaism by invoking a stereotype about the Jewish proboscis – “I always thought Jesus Christ was a Snubby or I should not have worship’d him – if I had thought he had been one of those long spindle nosed rascals” he was writing in what he thought was the privacy of a notebook. Blake’s most hostile remarks about Jews, in fact, appear where the public presumably was not to be invited. In his works intended for the public, he is more subtle, or at least more obscure, which might explain how Blake’s seeming antisemitism has managed to fly under critical radar.

Shabatei has interpreted Blake’s inconsistent position on the Jews as connected to his critical attitude toward deism and organized religion. In other words, Blake demonized deists generally, including “false” Christians and Jews, suggesting that his seeming antisemitism was a means and not an end. She writes,

[As] one critic speculates, “the Jews qua Jews were irrelevant to Blake, other than as the antagonists of his personal myth of the Christian dialectic.”‘

…

Blake wished to deter his readers from interpreting the Old Testament as a narrative of God’s dealings with a wayward and fickle nation. In his view, the Bible was a book of revelations, with “seers” emerging from time to time to reveal that the salvation of humanity lay in the recognition of Jesus Christ as the Saviour.

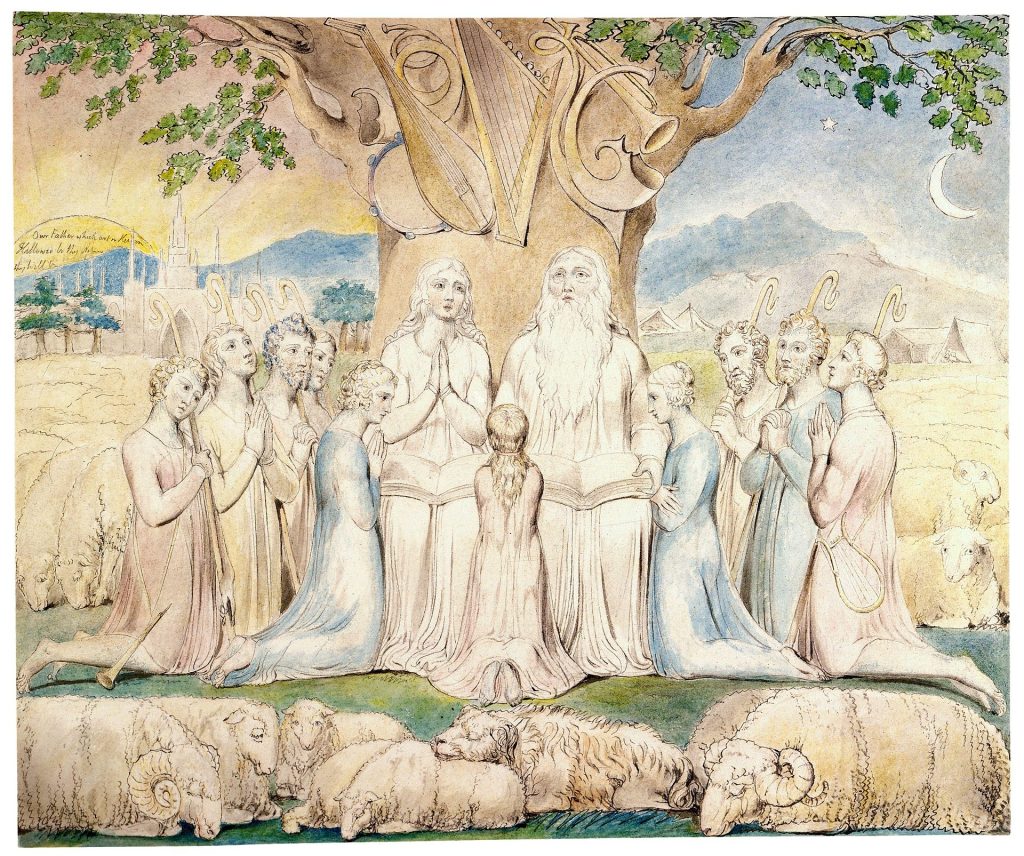

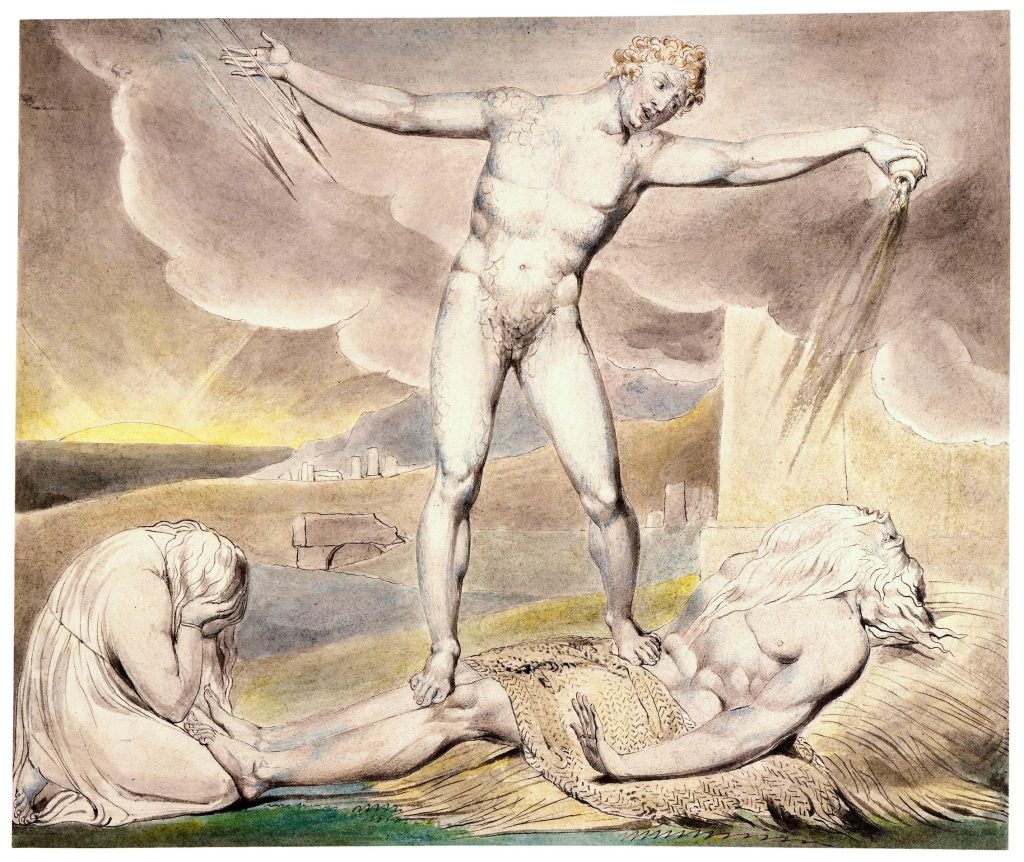

Blake’s illustrations for the biblical Book of Job reinforce this position. He created two versions, a watercolour series dating 1805 and an engraved set of plates made twenty years later. The first series was produced after Blake experienced a period of Christian regeneration.

A powerful parable about the limits of human faith, Blake’s early watercolours contain elements absent from the Old Testament text, and the overall narrative is tinged with Christocentric content. While Blake generally adheres to the story of Job in the Bible, he incorporates several personal motifs. In the beginning, Job and his family attend only to the letter of God rather than the spirit of God’s laws. Job falls under a false conception of God and into the hands of Satan, and although he is already an ancient rabbi, a man of prayer, his faith is deepened by suffering. Blake’s series culminates in renewed vision and reunion with God in Christ.

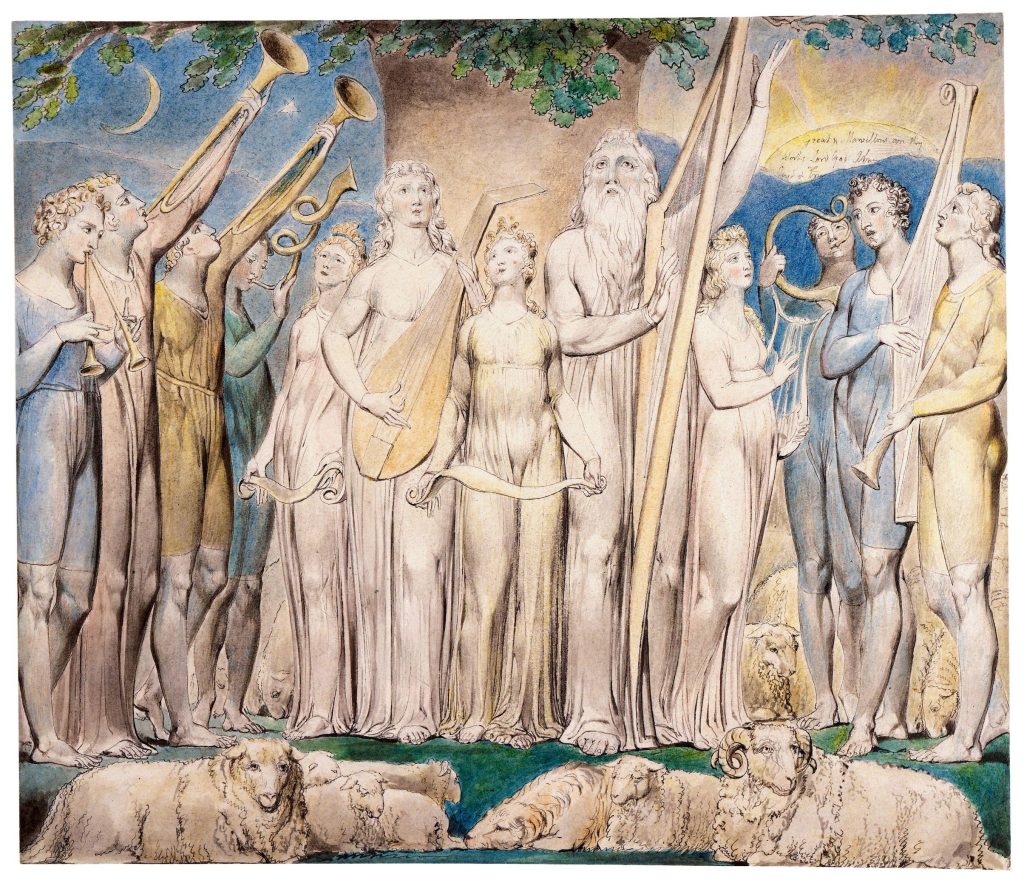

The first watercolour depicts Job and his life of peace and plenitude. He is shown seated beneath a large oak tree hung with musical instruments. His family is gathered around him in prayer. All around their tight-knit circle flocks of sheep stretch out into the landscape illuminated by a setting sun on the left and a crescent moon on the right. “Thus did Job continually” is inscribed in the design. But the Lord’s prayer also appears around the face of the setting sun, and a Gothic church in the background creates a contrast with the open book of Moses which Job holds, indicating Blake’s intention to incorporate both Old and New Testament imagery. The silence of the musical instruments and the setting sun are evocative of the absence of spirituality and, ultimately of God.

As an allegory of true faith, the central motif is suffering and redemption. In Blake’s rendition of the Book of Job, Job is a Pharisee, a prosperous and pious man whose spiritual journey is incomplete. Through Satan, he undergoes extreme hardship and complete loss but sees the light and is rewarded by God with the restoration of his health, wealth, and family.

In Satan Smiting Job with Boils, the figure of Satan, strong, vigorous, even graceful, dominates Job, pouring fire from a phial to afflict him with sore boils and fill him with sin. Job is now the embodiment of evil, conjuring up the ancient perception of Jews as spiritually diseased. In the distance, a burning sun sinks behind a black sea, suggesting spiritual death.

This perception of Jews as essentially decrepit was rooted in the earliest Modern Christian images, a characterization which came to signify their collective culpability for the Crucifixion.

In Job and His Family Restored to Prosperity, the musical instruments are being played to praise God, and the sun is rising, both potent symbols of redemption. The family is reunited in harmony with the synthesis of the Old and New Testaments as they are embodied in the Christian experience.

William Holman Hunt was also drawn to biblical subjects. However, unlike the inventive mysticism that characterized Blake’s oeuvre, Hunt sought to portray his Christian stories with literal authenticity.

The passion for the Holy Land, which gripped the British cultural imagination during the 19th century, was not just religious but political and economic as well, part of Britain’s expanding imperial identity. It opened the doors to the Middle East in unprecedented ways. It was a significant attraction for Holman Hunt and others who believed that personal experience was a fundamental element of faith and whose visualization of the Bible was inextricably linked to the Holy Land.

In 1848, Hunt, along with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais, founded a society of young artists in London. They called themselves the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later the Pre-Raphaelites), rebelled against the teachings and orthodoxies of the Royal Academy, and advocated a return to the purity and piety of the medieval era of the art before Raphael. They believed that art should be spiritual in character (as opposed to the materialist realism of Courbet and the French School) and sought to express authentically Christian imagery and ideology by painting religious subjects on a grand scale. Their inspiration lay in the contemporary theories of John Ruskin, who emphasized the connections between nature, art, and society. The Pre-Raphaelites saw themselves as a reform movement and published a periodical, The Germ, to promote their ideas.

Holman Hunt traveled several times to the Holy Land for authentic inspiration for his biblical scenes. Hunt’s strict adherence to the idea of “truth to nature,” that artists should look to the visible world directly when they paint, was part of his investment in the principle of spiritual truth and his belief that the artist’s responsibility was to promote and uphold moral integrity.

Hunt’s first of four trips to Jerusalem was in 1854. In 1876 he built a house just outside the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem. Hunt’s justification for his trips to the Holy Land fit the paradigm of the Orientalist explorer-adventurer-artist-author as defined by Edward Said in Orientalism (Pantheon Books, 1978).

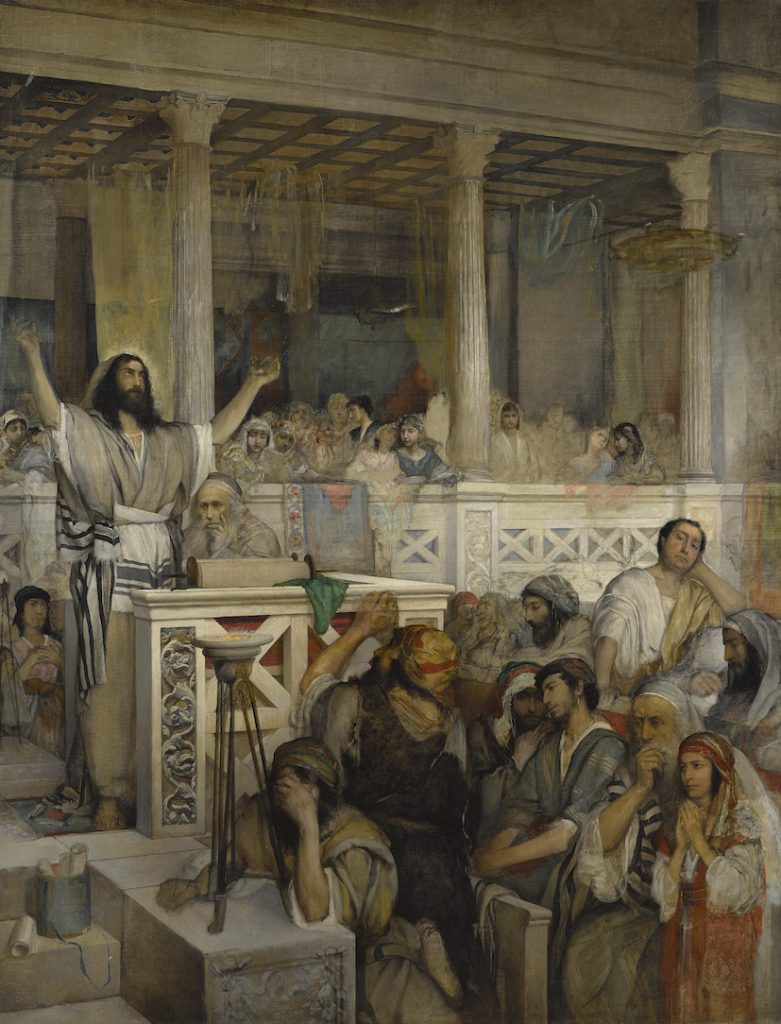

The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple portrays the young Jesus in discussion with rabbis in Herod’s temple in Jerusalem. The scene refers to the Gospel of Saint Luke (2. 41-52). The twelve-year-old Jesus has become separated from his parents during their annual trip to Jerusalem for Passover. After three days, he is found in the Temple courts engaged in discussion with the rabbis, who are astonished at his wisdom. Mary asks, “Son, why have you treated us like this? Your father and I have been anxiously searching for you?” Jesus’ reply is: “How is it that ye sought me? Wist ye not that I must be about my Father’s business?” This then is the moment of Christ’s self-recognition: his conversion, his first realization of his appointed role on earth, and it is the moment that Hunt significantly addresses.

Despite any underlying agenda, Hunt sought historical and ethnographic precision, studying old Judaic traditions and customs. The architectural details in the painting (the position of the temple in relation to the background landscape and that of the original temple on Mount Moriah) and the costuming are accurate. Jesus wears common Arab garb, while the rabbis wear authentic rabbinical garments. Hunt’s failed attempt to find local models for his figures forced him to hire Eastern Jews in England, who were not told they were posing for this subject. Notably, Hunt came away from his close observation of Jewish customs repelled by the undue reverence for the physical material of the Torah. For example, the custom of kissing the scrolls’ coverings and bowing struck him as idolatrous. His depiction shows the boy kissing the cloth and keeping the flies away from Torah with a whisk.

When the painting was exhibited in England, the accompanying pamphlet by Frederic George Stephens was markedly disparaging. “Nearest of the rabbis is seated an old priest, the chief, who, blind, imbecile, and decrepit,” he writes of the rabbi clutching the Torah to himself “strenuously yet feebly; his sight is gone, his hands seem palsied . . . He is the type of obstinate adherence to the old and decayed doctrine and pertinacious refusal of the new.” He goes on to describe each of the rabbis individually. One is “eager, unsatisfied, passionate, and argumentative,” another “an envious, acrid individual, a lean man,” and yet another a “mere human lump of dough . . . a huge sensual stomach of a man, who squats upon his own broad base, and indolently lifts his hand in complacent surprise at the interruption.”

The work expresses the artist’s central concerns: Judaism’s rejection of the Messiah whom it professed to await, the embodying of the seven deadly sins (avarice, obesity etc.), and the ultimate betrayal of Christ and Christianity.

Nancy Davenport in “William Holman-Hunt: Layered Belief in the Art of a Pre-Raphaelite Realist” (Religion and the Arts, 16, (2012): 29-77) details the historical circumstances of the painting:

The particular project Hunt came to Jerusalem to paint was The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple. He had expected to hire Jewish models for the rabbis who had listened to Jesus preach as a young child in the Temple, and he had wished for the same in finding models for Jesus and his parents. However, he found this to be difficult, proclamations having been sent out to the Jews forbidding them to be models for him. And when some offered themselves as models and were told not to return, he had to start all over with new models, as accurate portraiture was his goal. Frustrated by the recurrence of these difficulties, Hunt decided to complete the painting in London on his return. And so he did, finding Jewish models and using as background his reconstruction of details from the Court of the Lions at the Alhambra and other Islamic buildings available in the 1855 Crystal Palace exhibition to represent the ancient Temple of Solomon rather than either a Palestinian or British synagogue.

…

Christ’s wide-eyed expression is prophetic and confrontational, his pose assured with feet squarely on the ground and knees locked …. He is a boy with a job to do, not concerned with the spirit, but with his message to the world. He seems also to be rejecting the motherly gesture of the Virgin and the solicitude of Joseph as he preaches his new and messianic truth to scholars of the ancient religion from which he has emerged as the Messiah. He assertively tightens his belt on which is placed a cross, symbol of his final suffering to which he pays no heed at this early moment in his ministry. Hunt has depicted the self-empowered child as one who is ignoring the past and speaking to the future. He is making ready to confront the world alone, dismissive of his roots. In the background on the right, workers are constructing a building, a new temple for this new religion. This painting reveals no ecumenical spirit, but rather a kind of arrogant assurance about the rectitude and morality of manly Christian virtue with little concealment of the artist’s conscious or unconscious antisemitism.

Davenport goes on to discuss Hunt’s change of attitude towards Jews and Judaism:

Thus, in the context of this latest and last transformation of Hunt’s religious beliefs as expressed in his art, it is useful to compare the appearance of his original The Finding of Christ in the Temple with a different version he painted of the same subject in 1887 after the second of his three stays [in Jerusalem]. Christ Amongst the Doctors, his one and only religious commission, exists in the form of a gouache done in 1887 for a mosaic, which was never fired, ordered by Archbishop Wilson for the Chapel of Clifton College in Oxford. Rather than a determined and self-motivated Christ child as in the first conception of the work, Hunt represented a gentle and benign young man with graceful curls holding an ancient Hebrew scroll open on his lap to the text from Isaiah prophesying his coming as the Messiah. No longer girding his loins to face the world, Christ touches his forehead with his left hand, pondering the scroll’s meaning or conceiving a response to it. And rather than the critical and defensive group of Pharisees as in the earlier painting, Hunt represents the same older men as benign and attentive, their blind patriarch no longer present, awaiting the young Christ’s response in relaxed and in no way accusatory postures. Three young boys, in the original conception guarding the scrolls and otherwise concerned with protecting the ancient blind Pharisee, now observe Christ attentively, waiting for his response. Here, members of the two religions are conversing. The faces of the Pharisees are no longer startling caricatures, but gentle and restrained adults in dialogue with a thoughtful, not an assertive adolescent. The ancient and the new religions have merged in this version of Christ in the Temple representing Hunt’s transformed sense of Biblical history. Christ and the Pharisees share a place, exchange points of view, and are at peace. This image seems to be a conscious contradiction to The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, even, perhaps, an apology for an earlier and more limited viewpoint. It is a subject not referencing conversion but merely conversation. Hunt was, by this time, acquainted with the leaders of the Jewish community leaders …, sent there by Sir Moses Montefiore, the influential Jewish MP in London, to promote peace and begin discussion about the possibilities of a Zionist state in Syria. This image, created for an Oxford chapel, is the result of the artist’s more ecumenical point of view, distanced from any sense of Christian mysticism and as well from any celebration of Victorian Christian manliness.

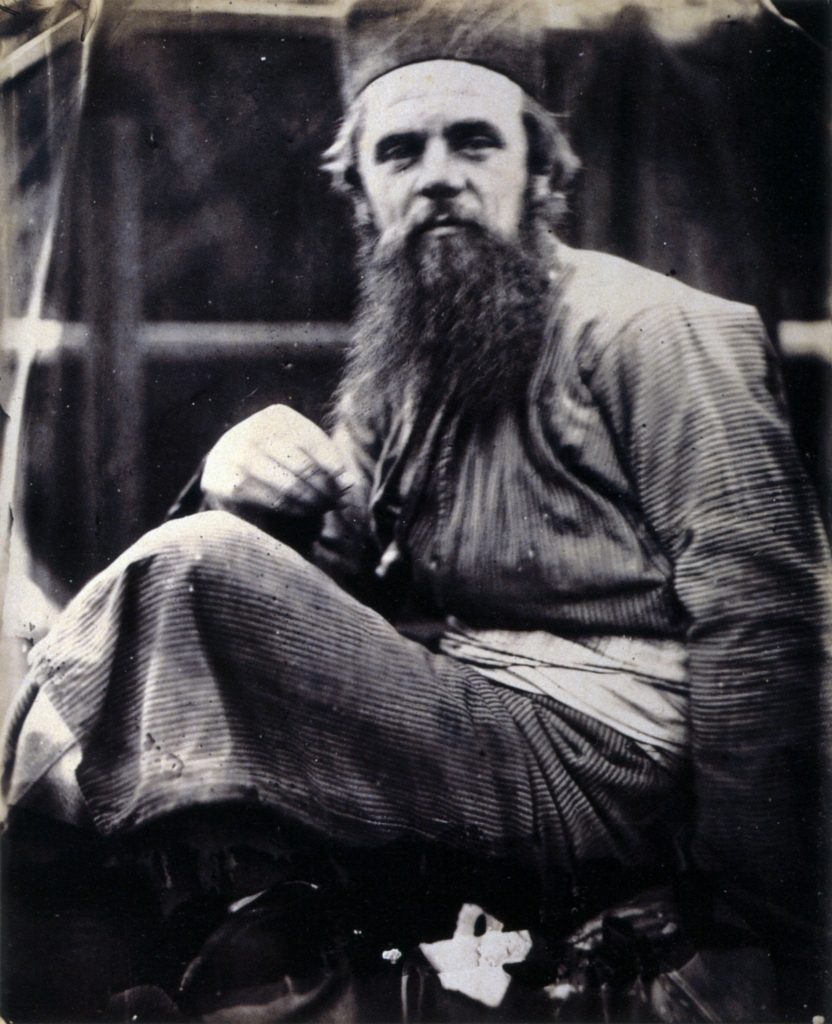

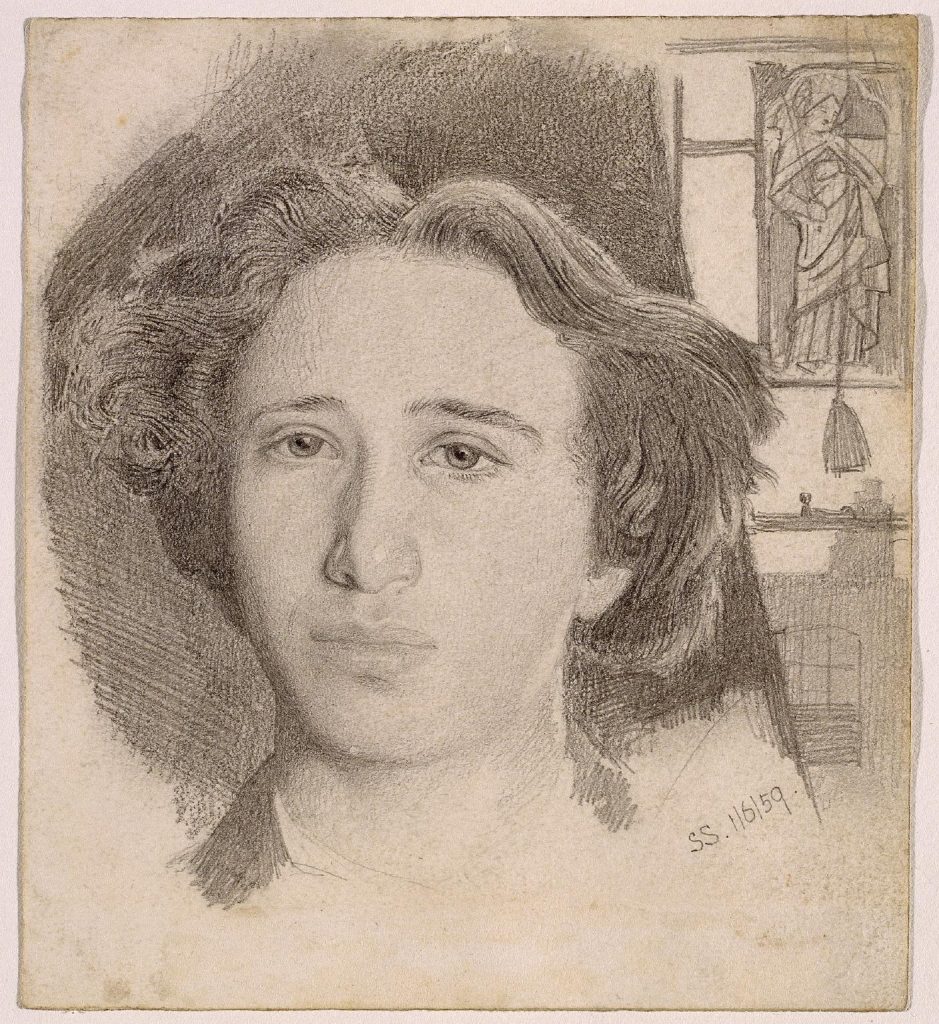

An interesting comparison may be found in the Anglo-Jewish artist Simeon Solomon’s biblical subject matter. Solomon was associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, but his controversial lifestyle as a gay man, and possibly his Jewish heritage, aborted his career early on. He was born in London in 1840 to a middle-class, fully assimilated Ashkenazi family. His brother, Abraham, and sister Rebecca, were also practicing artists. For a while, he successfully navigated the modernity of Victorian England, producing works with clear Jewish themes, highly unusual among the generally explicitly Christian movement. He also created a body of work depicting same-sex romantic desire. Overall, his paintings and drawings were informed by a complex mix of Victorian evangelical piety, a Pre-Raphaelite interest in close observation and truth to the subjects and traditions of Judaism.

Solomon was admitted to the Royal Academy at fourteen in 1854. While the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had lost cohesion by this time, their aesthetic influence continued through exhibitions of their works, and their ideas were accessible through The Germ. He began working in Pre-Raphaelite circles gaining recognition for his imagination and innovation. The Pre-Raphaelite ideas about art as fundamentally spiritual provided a framework for him to explore his own religion and spirituality. Solomon did not abandon his Jewish world for success. Rather, he used his Jewishness as a source of inspiration and a validation of the vanishing past of pre-emancipation Judaism.

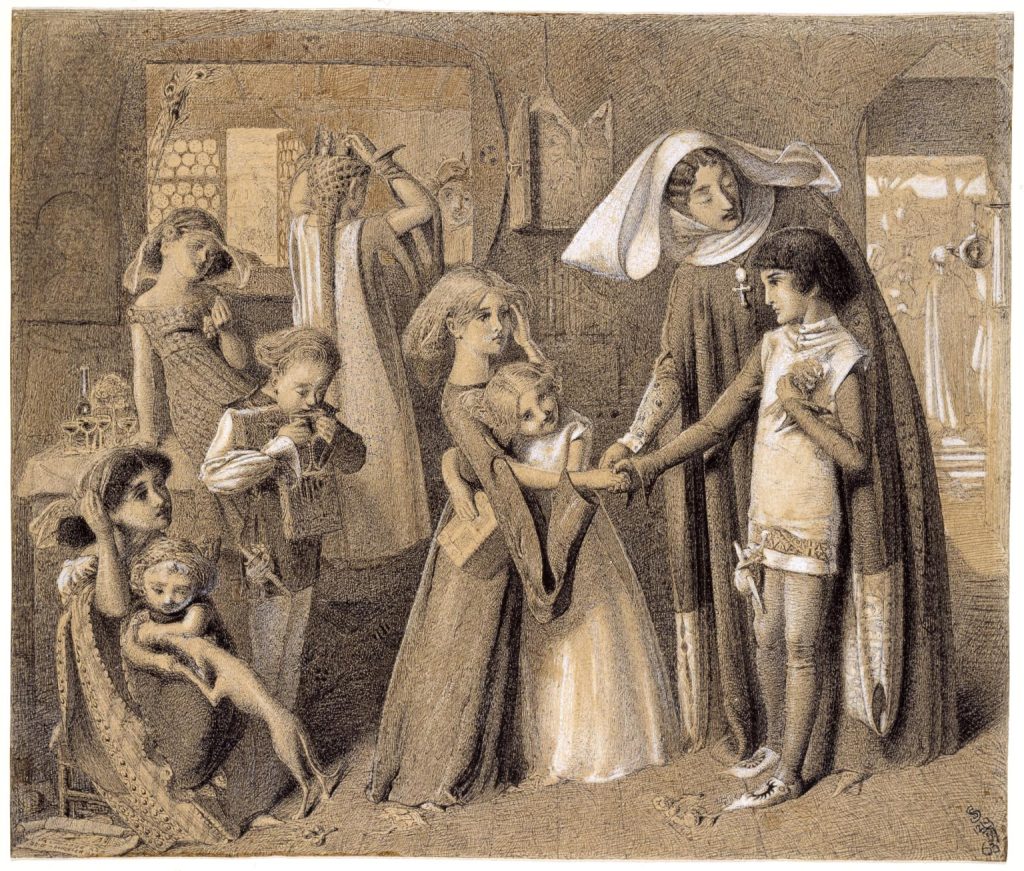

Solomon’s work was influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites stylistically as well as thematically. When he became acquainted with the Rossetti and Burne-Jones circle, he took part in the contemporary revival of book illustration, creating decorative art for William Morris. Here the subject of the drawing derives from Dante’s Vita Nuova, specifically the moment the poet first meets Beatrice, his idealized love, ‘at the beginning of her nineth year almost.’ Rossetti, a great admirer of Dante, most likely influenced Solomon’s subject choice.

The Mother of Moses exemplifies Solomon’s interest in the authentic representation of historical subjects. It depicts the Old Testament story of Jochebed holding the infant Moses before abandoning him by the Nile in the wicker basket his sister Miriam holds here. Solomon’s model was the Jamaican-born Fanny Eaton, a working-class black woman who went on to model for several of the Pre-Raphaelite artists.

Karin Anger describes the significance of Solomon’s image sources and his sitter in “Truth To (His) Nature: Judaism in The Art of Simeon Solomon” (Constellations, 9 no. 2 (2018) (https://doi.org/10.29173/cons29349)

The fact Solomon used a model who was obviously not white, a visible other as a model for biblical figures in a time where idealized beauty as white was a given is fascinating. Solomon’s Jochaved and Miriam are (to a Victorian eye) visibly Jewish, tightly curled dark hair and all, presenting a clear other to a Victorian audience. The Victorian interest in phrenology, studying the face to understand the ethnic background and character of a person, comes into play here. For a Victorian audience with this interest in phrenology, there would be no doubt these women were Egyptian Jews. Some of this certainly came out of the interest in truth to nature and historical accuracy Solomon shows in other aspects of his biblical works, but by making this choice to show these figures as Jews, Solomon consciously points out that this painting is not about Christianity. Solomon does not make Jochaved and Miriam stereotypes, but rather they are shown as Jewish and dignified at once. This scene is rather lovely; it is a tender, human moment and at the same time it is overtly, unashamedly Jewish.

Ideas surrounding phrenology informed many artists’ depictions of Orientalist subjects during this era, enhanced by literary and visual motifs that entered the cultural imagination.

10.3

| Imaging the Jewess: La belle juive / L’affreuse juive

There is a worthwhile comparison to be made between Biblical representations of the female Jew, as seen in the works of Solomon, versus the stereotypical imagery which emerged during the 19th century across Europe, particularly in France.

Apart from the biblical popularity of the Holy Land, artists’ yearnings for the exotic east in the 19th century extended to an obsession with middle eastern female beauty, providing a place of honour to the Jewess. From Delacroix to Moreau la belle juive became an important motif in the Romanticist artistic production of the era.

Often grouping Turks, North Africans and Greeks beneath an orientalist umbrella, some artists traveled to North Africa and the Levant in search of models of this ideal beauty. Others scoured the Marais, the Jewish ghetto outside of Paris for their subjects. Through literary and artistic representations, the “Oriental” beauty of the Jewish female became a cultural emblem in France in the 1830s, 1840s, and the beginning of the 1850s.

As Marie Lathers describes in “Posing the ‘Belle Juive’: Jewish Models in 19th-Century Paris” (Woman’s Art Journal 21, no. 1 (2000): 27–32)

Jewish models were ubiquitous in mid-19th-century Parisian studios, valued for their exotic beauty and a supposedly inherent shamelessness (they do not know they are naked). Louis Leroy explained this preference: “Jewish women have had, and still have, a monopoly on modeling. Their original beauty and a certain disdain for what others think predisposes them very naturally to the model’s situation.

The belle juive was characterized by dark hair and eyes, an oval face with an olive or ivory tint, arched eyebrows, full lips, and graceful hands. Josephine Marix was a popular Jewish model who embodied the stereotype. Artists from Ingres and Delacroix to Steuben and Paul Delaroches chose her to pose for their narrative and history paintings, . Jules Clarétie, writing in La vie à Paris, 1881, described Marix’s desirability thus, “This model loves her art, truly collaborates with her painter, shares his fever and his anger.”

While the stereotype of la belle juive was a ‘positive’ characterization in early and mid-19th century France, it was significantly eroded by the next wave of antisemitism that swept the country. Social fears and unrest, compounded by the controversial imagery surrounding the trope of la femme fatale acutely altered the symbolism .

Marie Lathers:

As the century progressed, the Jewish model’s relationship to race as a category mutated; as Judaism was increasingly understood in terms of race (or blood), la juive was called upon to represent the conjunction of two increasingly suspect bodies—Woman and Jew—and there was less room in her body for the ideal to be posed. A vulgarization of the modeling profession also accompanied the rise of misogyny and antisemitism, and these concurrent phenomena conspired to make of the Jewish female model an “ideal” example of the convergence of three dangerous bodies: Woman, Jew, and model.

Whereas the Jewish woman was tolerated-indeed, celebrated-in Delaroche’s atelier (despite the mysterious illnesses that she may have provoked), the atelier of the fin de siècle demanded that the Jewish model be erased as ideal—she was now Salome, the incarnation of fin-de-siècle fears of women who were also Jews … the belle Juive mutated into the femme fatale and the muse became professional model and then vampire.

Christina Leah Sztajnkrycer in “The Jewish Capital of Europe: Literary Representation from Balzac to Proust of the Societal Place and Architectural Space of Jews in Paris from the July Monarchy to the Belle Époque” (PhD diss., University of Washington, 2016) elaborates further:

The transition from belle juive to affreuse juive is evidence of the changing appreciation of the Jewish population in France, particularly in Paris. The idealized belle juive became an image of the early period in which Jews were still working to adopt a more French identity and the affreuse juive inaugurated the later period in which Parisians were finding it very difficult to accept the remarkable assimilation of some highly visible and powerful elite Jews.

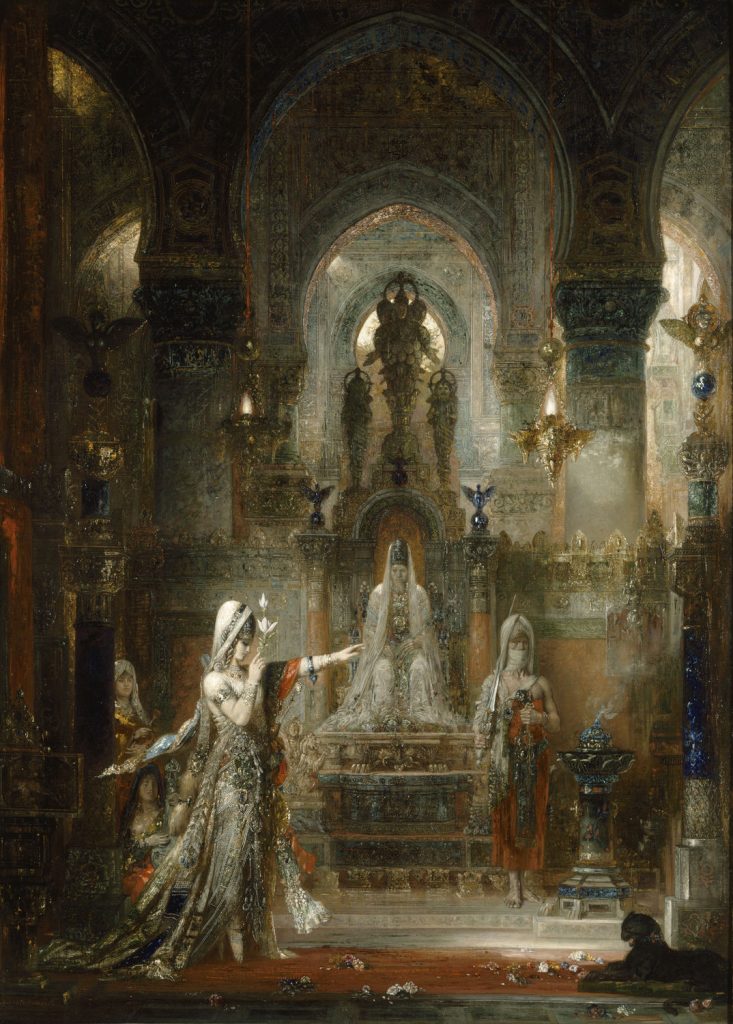

The Symbolist artist Gustave Moreau’s focus on the Salome theme was part of a large body of visual and literary works that advanced the trope of the Jewish femme fatale in the late 19th century. Here, Moreau chose to cast the Judean princess as a lustful, vengeful murderess.

In The Apparition, Salome, having bewitched her stepfather Herod Antipas with her dance of the seven veils, receives her reward: the head of the man who shunned her, John the Baptist. The painting created a sensation at the Paris Salon. Visitors were captivated by Moreau’s lush and exotic imagery, and mesmerized by the enigmatic, sensuous female figure. The Apparition depicts the head of the prophet hovering above Salome, who stands very still beneath the glowing, radiant light he emanates. An otherworldly energy binds them together as it eclipses the figures of the king, his wife, and the executioner, whose sword still drips with blood.

Moreau drew inspiration from varied sources for his intricately detailed images, including antiquity, Renaissance paintings, and the Near and Far East, the latter informing the decorative elements and the jewellery, for instance, the “magic rings” and “the mirror of Solomon” believed to be employed for divination. Contemporaneous literature further augmented the works’ visual resonance, for example, Joris-Karl Huysmans’s decadent 1884 novel, À rebours (Against Nature), as described in Peter Cooke’s “‘It isn’t a Dance’: Gustave Moreau’s ‘Salome’ and ‘The Apparition,’”(Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research 29, no. 2 (2011): 214–32:

In the perverse smell of perfumes, in the overheated atmosphere of this church, Salome, with her left arm extended, in a gesture of command, and with her right arm folded, holding a large lotus flower level with her face, advances slowly on her toes, to the chords of a guitar whose strings are plucked by a squatting woman. With her meditative, solemn, almost august face, she begins the lubricious dance which is to awaken the slumbering senses of the aged Herod: her breasts undulate and, rubbed by her whirling necklaces, their nipples stand up; on her moist skin the diamonds glitter; her bracelets, her belts, her rings spit out sparks; on her triumphal robe, sewn with pearls, decorated with gold lamé, with silver in leafy patterns, her armour of gold and silverwork, in which each link is a precious stone, goes into combustion, criss-crosses snakes of fire, swarms on her matt flesh, on her tea-rose skin, like splendid insects with dazzling wings, marbled with carmine, spotted with dawn yellow, mottled with steel blue, striped with peacock green. Concentrated, with her gaze fixed, like a sleepwalker, she sees neither the trembling Herod, nor her mother, the ferocious Herodias, who is watching over her, nor the hermaphrodite or eunuch who is standing, with his sword in his hand, at the foot of the throne, a terrible figure, veiled down to the cheeks, and whose castrato’s breast hangs, like gourds, under his gaudy orange tunic… Moreau, like Huysmans, has translated the narrative into a metaphor for the seductive power of Woman, and the formidable power of sexual desire.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the trope of female seduction based on Salome, the “natural, that is to say abominable” woman (in Baudelaire’s words), had become a prevalent motif in France as well as Britain, figuring in the decadent imagination of the day and inspiring painters, poets and novelists. While Cleopatra, Judith, or Delilah equally personified the trope, the biblical Salome, who caused the beheading of the prophet John was the most powerful and charismatic characterization.

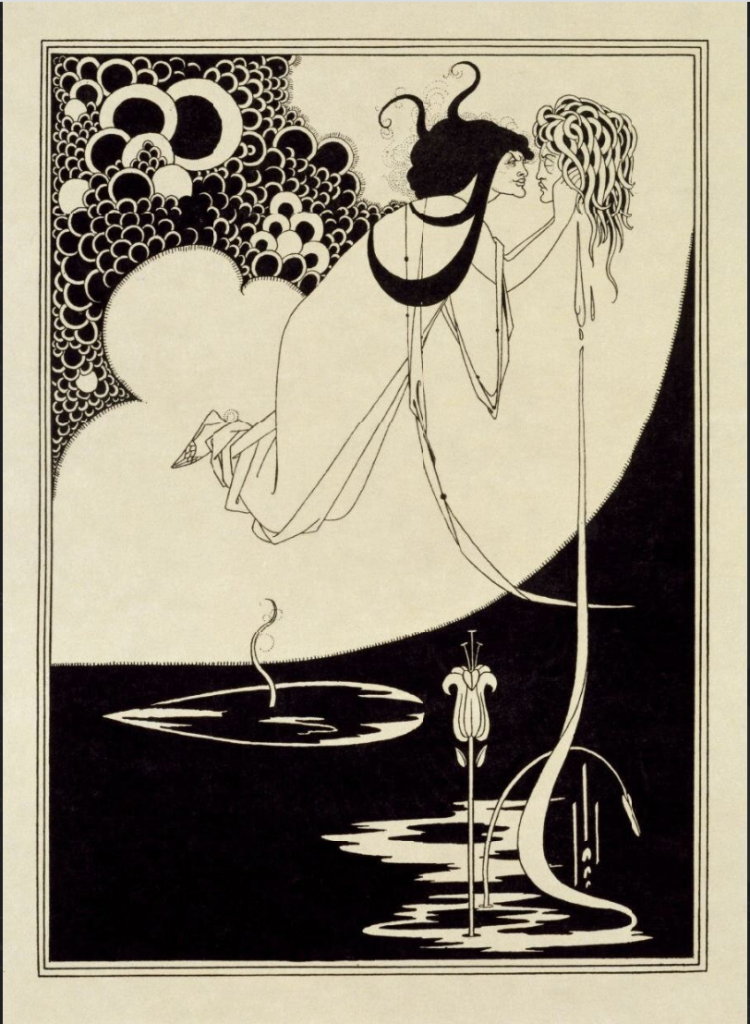

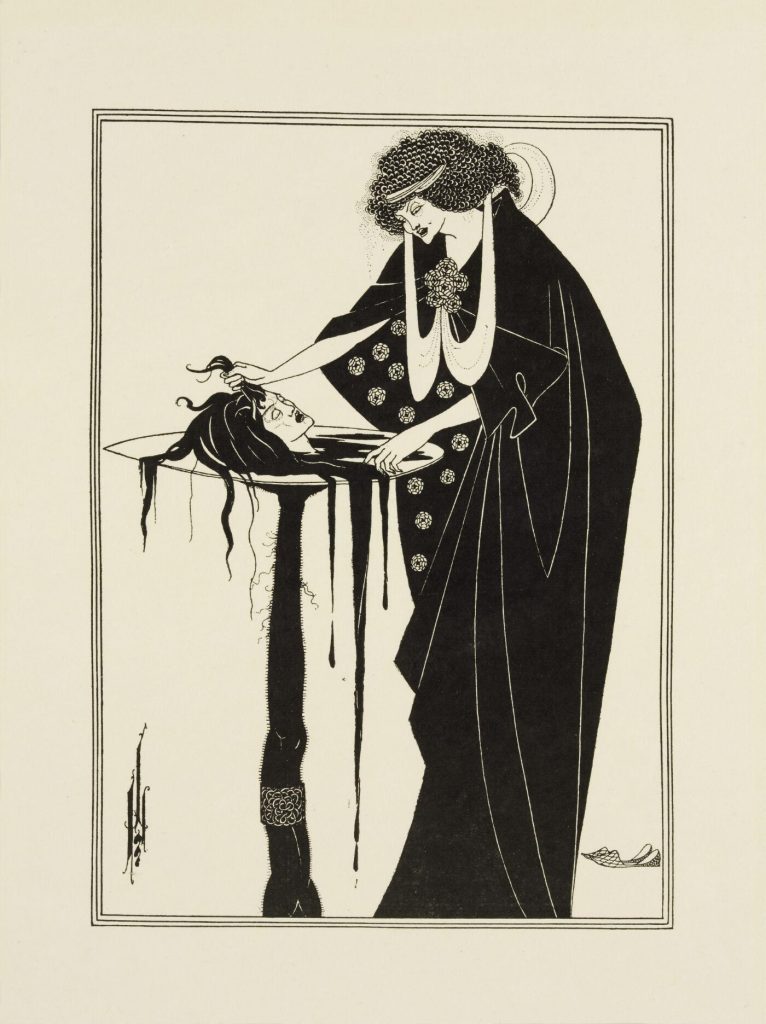

Oscar Wilde’s play, Salome (1893), was one of the most striking interpretations in the history of literature. Cruelty, sacrilege, strangeness, and eroticism comingle in this play which Pierre Loti described as beautiful “and dark like a chapter in the Apocalypse.” When Wilde’s play Salome was first published in February 1893, the Pall Mall Budget magazine asked Aubrey Beardsley, a leading figure in the British Aesthetic movement whose drawings embraced decadence and the grotesque, to contribute an illustration. He based the first macabre image around the last scene in the play when Salome embraces the severed head of John the Baptist.

In Oscar Wilde’s version of the story, the prophet refuses Salome’s kiss, an act which ended his life and which offered up a convoluted analogy to the Judas kiss, the kiss of death, which ended the life of Christ. Both stories speak to the notion that the death of Christ was by Jews.

Beardsley’s drawings of Wilde’s play are perhaps his most celebrated for their virtuosity of form and content. They did not, nor were they expected to, faithfully illustrate specific scenes in the play but instead acted as visual commentaries. Executed in stark black and white, they present a world at once lyrical and strange, completely eroticized, and blatantly nonconformist. Beardsley transfigures “sin” into abstracted beauty, effectively conveying degradation as desirable and seductive. The imagery Beardsley went on to produce in all the illustrations for the play addressed a stereotypical Salome, the quintessentially deceptive and dangerous Jewish woman.

Jeffrey Wallen, in “Illustrating Salome: Perverting the Text?” (Word & Image 8, no. 2 (1992): 124-132), compares the play to the illustrations:

Salome, as the interpretative fulcrum of the play, functions therefore very much akin to Beardsley’s illustrations. Salome enables us to ‘see’ that which is rendered obscure by the other characters: the vulnerability of the existing patriarchal order, and the disruptive, revolutionary force of unsublimated desire. Furthermore, Salome herself incarnates that which is being exposed: the spectacle of ‘illicit sexual desire.’ An emphasis on the interpretative force of gender and female sexuality, although it offers a different ground than attention to the relation between text and image for understanding the oppositions between veiling and exposure, and between an aesthetic and a perverse form of visual desire, still depends on a similar interpretative model of illustration. Both of these lines of interpretation – using the illustrations, or the figure of Salome to explicate the text; privileging the visual, or the sexual – involve a reversal of the traditional aesthetic relationship between the sensual and the supra-sensual. The sensual, and the sexual, rather than leading to the higher truths of the mind and the spirit, are themselves, from this perspective, the truth that is revealed once the rhetorical illusion is dispelled. Moreover, Salome is the play of this reversal – the head of the prophet is severed, and served up on a silver charger, as aesthetic and erotic object.

By the turn of the 19th century, the dangerous femineity of the Jewish woman gained ground, becoming a visual analogue of the German proverb: “God created the Jew in anger, the Jewess in wrath” (that is, the Jewess is even worse than the Jew).

Gustav Klimt, a Viennese Modernist, also adhered to traditional portrayals of Salome in the nineteenth century. As well he includes elements of the original biblical story and others adopted from Near and Far Eastern art.

Susanne Kelly, in “Perceptions of Jewish Female Bodies through Gustav Klimt and Peter Altenberg” (Imaginations Journal 3, no. 1 (Summer 2012): 109-122), writes:

Klimt displays many of the elements of the biblical oriental story and inserts elements adopted from Egyptian, Japanese, and Chinese art, but gives his main subject what his contemporaries recognized as distinctly Jewish features. Commenting on Judith I, Felix Salten states, “One often encounters such slender, glittering Jewish women and longs to see these decorative, flirtatious and playful creatures suddenly hurled toward a horrid destiny, to detonate the explosive power that flashes in their eyes.”

Klimt’s images realized the prevalent fantasy of sex associated with the dangerous Jewess. His representations fused the misogyny and antisemitism that characterized fin-de-siècle thinking. In these Judiths, Kelly emphasizes, “sexuality, Jewishness, and the Oriental merge to convey a powerful and dangerous woman, known for male fatality.”

Bram Dijkstra, in Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siecle Culture (Oxford University Press, 1998), explains that it was in the late 1870s when Moreau, Beardsley and Klimt were painting Salome, that the term antisemitism surfaced. It originated in the idea that Hebrew is a Semitic language linking Jews to a wide swath of ancient and modern peoples from southwestern Asia, including the Akkadians, Canaanites, Phoenicians, and Arabs, who were themselves not victimized by the hatred and prejudice of antisemitism.

According to Dijkstra, the allure of Salome was rooted in antisemitic assumptions about Jewish sexuality. During the late 19th century and well into the 20th century, society considered Jews, women, and Africans degenerate. Moreau, Beardsley, and Klimt propagated the notion in their visual depictions of a Salome whose appearance displayed her degeneracy.

Accordingly, by the fin de siècle, Salome was guilty not only of the decapitation of John the Baptist but for her violent humiliation and symbolic emasculation of all men. Dijkstra concludes his book by linking gynecide, the killing of women, to genocide. The term genocide means the deliberate killing wholly or in part of a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. He argues that the violence felt towards the femme fatale at the turn of the century later shifted from the “Woman Question” to the “Jewish Question” and the Holocaust.

At the turn of the century, so-called scientific knowledge about human biology, psychology, genetics, and evolution, was employed by intellectuals and politicians to advance a racialized analysis of the Jew. This analysis was also based on a perversion of evolutionary theory as social Darwinism that popularized notions about the inequality of races and the superiority of the white race. As such, Jews behaved the way they did because of innate racial qualities. Racial eugenics, which contributed to this pseudoscientific discourse, argued that Jews were not only spreading their destructive political and economic influences to weaken nations in Central Europe but were polluting so-called pure Aryan blood by intermarriage and sexual relations with non-Jews. This pernicious perception of the Jews and the belief that this weakening of host nations was part of a secret Jewish plan for world domination led to the Holocaust during the Second World War.

The Holocaust was the systematic murder of six million Jews during the Second World War by Nazi Germany and its collaborators in Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, France, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia. Six million Jews across German-occupied Europe and around two-thirds of Europe’s Jewish population were murdered between 1941 and 1945. While the vast majority of victims of the Holocaust were Jews, many other minority groups were also targeted. Jehovah’s Witnesses, Roma (Gypsies), homosexuals, people with disabilities, and others were imprisoned in concentration camps or killed during the Holocaust. While the Nazi German regime did not have an organized program to eliminate African Germans, the regime discriminated against and persecuted them. Some black people in Germany and German-occupied territories were isolated; an unknown number were sterilized, incarcerated, or murdered.

10.4

| Moritz Daniel Oppenheim: “The Rothschild of Painters”

Two fundamental changes made possible the emergence of the modern Jewish artist in the 19th century. The first was the Haskalah, often termed the Jewish Enlightenment. This was an intellectual movement amongst Jews of Central and Eastern Europe that had two objectives: the cultural and moral renewal of Judaism through ideas that promoted rationalism and freedom of thought and encouraged secular education and literacy in modern languages as well the revival of Hebrew, and Jews’ integration into society through participation in occupations previously prohibited, such as the sciences and the arts. Haskalah made it possible for 19th century artists of Jewish origin to produce art at all.

Before emancipation, Jewish artists were isolated and confined to ghettos set apart from the mainstream. Often, the ghettos were enclosed by gated walls that were locked at night and during Christian holidays to ‘safeguard’ against potential evil acts. Impossible to expand laterally, houses were built upwards, becoming congested, unsanitary, and virtual fire hazards. Movement beyond the ghetto, however made Jews susceptible to harm and harassment.

Moritz Daniel Oppenheim, born in Hanau, Germany, in 1800, grew up in a devoutly religious home in the ghetto. Until 1806, he attended heder, a school for Jewish children in which Hebrew and religious knowledge was taught, and Talmud Torah for instruction in Judaism. With Napoleon’s conquest of the continent at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries, the concepts of liberty, fraternity and equality spread into Central Europe. German Jews were emancipated, and the ghetto gates were torn down. Oppenheim then went to a secular school. He was the first Jewish painter to receive training at the Hanau Drawing Academy and to study in Frankfurt, Munich, Paris and Rome.

This work, painted at the age of sixteen, is one of the earliest self-portraits by a Jewish artist of the modern era. Oppenheim’s self-image is confident and fashionably dressed. He holds a palette and brush in one hand and a mahlstick, a tool placed across a painting to steady a painter’s hand, in the other, openly declaring his status as an artist. A plaster cast of an ancient Greek sculpture and a sketch of a cherub resembling a painting by Raphael emphasize the young artist’s classical training. His dress, pensive demeanour, and casual pose suggest his prideful creative awareness and understanding of the history of art.

When Oppenheim was in Rome, he came under the influence of the Nazarenes, a group of fervently Christian artists who painted biblical scenes. Returning to Frankfurt in 1825, his own biblical paintings were soon widely appreciated. His most loyal patrons were the Rothschilds; he was known as the “painter of the Rothschilds” and, because of his success, as “the Rothschild of painters.”

Oppenheim rapidly gained recognition in non-Jewish circles as a portraitist of prominent Jews and gentiles. By his twenties, he was already celebrated as an important portraitist, and between the 1830s and the 1850s, he claimed the title of official portraitist to the Rothschild family.

The Rothschilds had risen from the Jewish ghetto in Frankfurt during the 18th century to become a major international banking dynasty in the space of a single generation. Mayer Rothschild and his five sons, pioneered the evolution of international finance, establishing branches in London, Paris, Vienna, and Naples, in addition to their native Frankfurt. Once one of the wealthiest families in the world, they inevitably shaped the world of finance and politics.

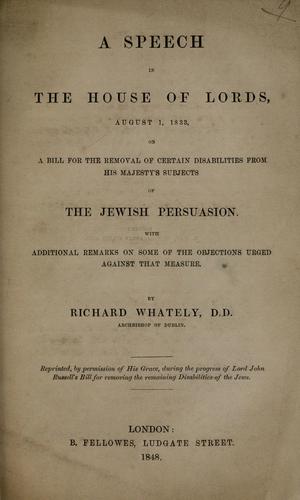

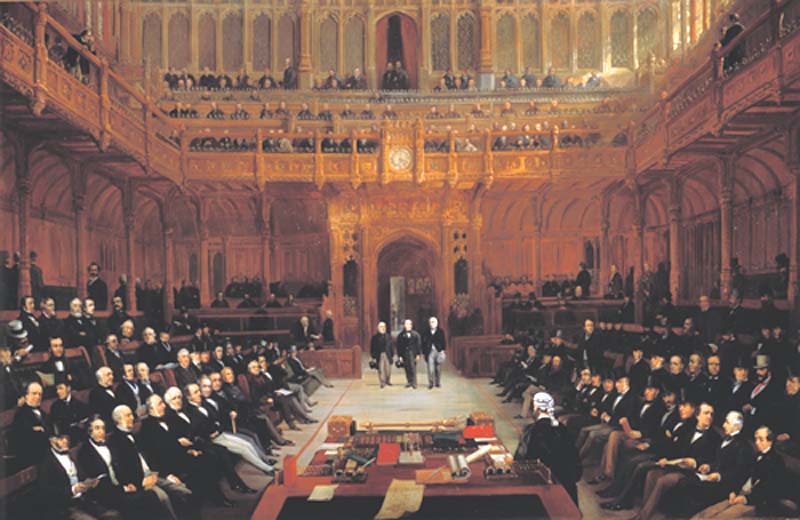

In London, Lionel de Rothschild (1808-1879), the grandson of Mayer Rothschild, entered politics and was elected as a Member of Parliament for the City of London in 1847. He would only assume his seat as Liberal Member eleven years later in 1858, as Jews could not take the Christian oath required to be sworn in. Prime Minister Lord John Russell introduced a Jewish Disabilities Bill to resolve the issue. In 1848, the bill was approved by the House of Commons but was twice rejected by the House of Lords. In 1850, he entered the House of Commons to take his seat but requested the Old Testament instead of the Christian Bible for his swearing-in, which was approved. His omission, however, of the phrase “upon the true faith of a Christian” was not.

Rothschild was re-elected in 1852 but did not take the oath until 1858 when Benjamin Disraeli became the Leader of the House of Commons. Disraeli, of Jewish birth, although converted to Christianity, wanted to avoid the position where his Conservative Peers in the Lords should block the Jewish Disabilities Bill. The House of Lords agreed to a proposal whereby each house would decide its oath. On July 26, 1858, Rothschild took the oath with covered head, substituting “so help me, Jehovah,” and taking his seat as the first Jewish member of Parliament. An eleven-year struggle thus ended with a simple ritual that nevertheless represented a significant step forward in the long campaign for religious freedom and Jewish assimilation.

Rothschild’s political platform embraced several reformative social issues, but he was committed to incorporating Jewish emancipation into the broader Liberal agenda of civil and religious liberty. He served as MP for sixteen years. In 1859, his brother, Mayer, was elected MP for Hythe in Kent. In 1865 his son Nathaniel became MP for Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire, where the Rothschilds owned property. Despite their financial and political success and service, the Rothschilds’ struggles for public acceptance illuminate the prejudicial challenges faced by Jews striving for social acceptance in Britain.

Oppenheim endeavoured to historicize the narrative of the Rothschilds. In The Elector of Hesse Entrusting Mayer Amschel Rothschild with his Treasure, Oppenheim presents a realistic, albeit romanticized, depiction of a significant event – delivering the Elector’s treasures to the patriarch of the family, Mayer de Rothschild, for safekeeping. Napoleon had annexed the lands of William I of Hesse in 1806. Still, much of his wealth was smuggled out of the electorate, and the Rothschilds successfully managed his assets. The relationship was mutually advantageous. The painting aimed to emphasize the family’s integrity in business dealings and legitimize the source of their wealth.

Oppenheim’s embrace of genre and emphasis on narrative places him outside the stream of new aesthetic developments. If Oppenheim is referred to as the first modern Jewish artist, it is not because he engaged with contemporary art but because the content of his work was unafraid and original in its embrace of social change, particularly within the framework of Jewish emancipation. Grace Glueck explains in “ART REVIEW; Out of the Jewish Ghetto and Into the Mainstream” (New York Times, April 6, 2001):

A talented painter with solid grounding in technical skills, Oppenheim was by no means an innovator. More important to him than style was the content of his work, and artistic movements and trends passed him by. He identified with the upper classes, wanting to assert himself on several fronts: as an artist, a citizen and a Jew. Much of his work depicted representatives of the up-and-coming Jewish bourgeoisie: intellectuals, politicians, businessmen and artists. Rooted in Jewish tradition but challenged by political emancipation, they claimed their right to full participation in German society.

The Rothschild family contributed extensively to Oppenheim’s success, which he recounted in his memoirs (excerpts, Moritz D. Oppenheim, “Cedars of Lebanon: The Rothschild of the Painters,” Commentary February 1955, https://www.commentary.org/articles/moritz-oppenheim/cedars-of-lebanon-the-rothschild-of-the-painters/):

The patricians of Frankfort called on me. Moritz von Bethmann (the father), Jean Noé Dufay, and others came . . . and commissioned pictures. The wife of the Elector of Hesse also favored me with a visit and later wrote me a very gracious letter. All this recognition brought me honor, and numerous commissions. Particularly, I did many portraits for the wealthiest Jewish families, and was well paid for them.

Later, the Rothschild family gave me a lot of work to do. The branch that had been in Naples resettled here, and established a princely household, as did Baron Anselm and his art-loving wife, Charlotte. I was invited to the most distinguished and dazzling social gatherings. . . .

Describing his professional relationship as an instructor to Baroness Charlotte, Oppenheim penned that the fact “…she was very satisfied with her teacher was shown by her frequent visits to my studio, and her amiable little letters to me in French. . . . She also had me decorate the cupola of her house. I decorated the eight panels with mythological subjects, presenting her as Psyche, without saying anything to her. She quickly noticed it. I also composed poems for her on special occasions…. But the culmination of my instruction came when she illustrated the Haggadah for her Uncle Amschel.”

Charlotte von Rothschild’s decision to create an illuminated Haggadah for the 70th birthday of her uncle was an innovative step into a realm of male endeavour. In “Charlotte ‘Chilly’ von Rothschild: Mother, Connoisseur, and Artist,” Evelyn M. Cohen points out that it was the earliest Hebrew manuscript documented as having been illuminated by a woman, an illuminated codex that referenced Jewish sources, as well as medieval Christian illuminations, and the latest developments in nineteenth-century art. “As such, Charlotte and the Haggadah she created were not only of her time, but ahead of her time.” (The Rothschild Archive: Review of the Year April 2012 to March 2013, 26-36. https://www.rothschildarchive.org/materials/review_2012_2013_complete_pdf_reduced.pdf)

Oppenheim’s The Return of the Volunteer depicts a young soldier in the Wars of Liberation against Napoleon who has defied Sabbath travel prohibitions to visit his family. Showing the emancipated son as he clasps the hand of his tradition-observing father, Oppenheim touches on the conflict between the demands of religion versus new responsibilities of Jews as citizens. It is generally considered the first effort of a known Jewish artist to confront a specifically Jewish subject.

The Return coincides with political turbulence in the wake of the 1830 revolutions and Germany’s reimposition of repressive Jewish legislation.

Popular in early-nineteenth-century art, images of departing and returning volunteers served as sources for Oppenheim’s work. Oppenheim must have followed the career of his fellow Hanauer Johann Peter Krafft, whose paintings The Departure of the Militiaman (1813) and The Return of the Militiaman (1820) were bought by the Hapsburg emperor.

10.5

| The Politics of Genre

The Return of the Volunteer is Oppenheim’s most overtly political painting, and it is unusual in the context of genre art. It has been interpreted art historically as an image of affirmation of German Jewish patriotism and of the question of assimilation. Hundreds of German Jewish volunteers fought against Napoleon’s forces only to lose many of the civil rights they had gained under the French occupation when the French were defeated. From another perspective, the painting may be seen as the Jewish father’s ambivalence—pride at the military honour the Iron Cross represents and discomfort with its Christian symbolism.

Lisa Libicki analyzes The Return of the Volunteer in A Guide on Narration in Art. (https://s3.amazonaws.com/tjmassets/programs_educator_resources_pdf/JM_NarrativeArt_CurriculumGuide.pdf):

The soldier’s mother and siblings appear in various states of concern and delight. Some direct their attention to the soldier himself while others peer at his uniform and other military accoutrements. The father looks at his son’s Iron Cross, a military decoration that is also a Christian symbol. The father’s gaze seems to betray an inner struggle to resolve conflicted emotions of pride, concern, and anxiety. The Return of the Volunteer was painted at a time when Jewish civil rights in Germany were in a tenuous state. In the wake of the political unrest following the 1830 revolutions in France and their reverberations in Germany, many German states reimposed repressive legislation that affected rights recently won by Jews. Art historians interpret this painting as a reminder to Germans of the significant role played by Jews in the Wars of Liberation, some twenty years earlier. Beyond the son’s military status, the hanging portrait of Frederick the Great, emperor of Prussia, is a visual indicator of the political context of this painting. Oppenheim’s painting suggests both a tension between country and religion and between generations—between the traditions of the old and the new ways of the young.

…

The Return of the Volunteer is set in a domestic dining room. A table in the center of the composition is draped with two tablecloths, one patterned, the other white. Atop the table are a half-eaten loaf of braided challah and a kiddush cup, details that let the viewer know it is the Jewish Sabbath. In this richly detailed setting, other objects of note are two plaques with Hebrew inscriptions, an open book on the table whose page layout identifies it as a Talmud, the family’s cat peering out from underneath the table, and the edge of a doorway at the picture’s far left.

…

Warm sunlight filters into the room through a large arched window in the center of the background. The time of day is most likely afternoon. A beam of light guides the viewer’s gaze toward the young man. Seated on a chair at the far left of the composition, the man is wearing a blue and gold military uniform, adorned with an Iron Cross, which identifies him as the soldier in the title. The soldier is looking off toward his sister, who leans over him. Standing in the foreground, just right of center, the soldier’s mother looks at him; a tear is streaming down her cheek. She wears a red coat and white satin skirt. The soldier’s father, sitting behind him and to his left, holds his son’s hand and looks intently at the Iron Cross on his chest. In the center of the background, two younger siblings look over at the soldier, though their gazes appear to be fixed more on his uniform than on him. A third sibling on the right is the only character whose gaze is directed away from the soldier. He seems preoccupied with looking at the soldier’s accoutrement.All the men and boys in the picture, with the exception of the soldier, wear traditional Jewish skull caps. The soldier is the focal point of this scene. In addition to the light streaming toward him, which leads the viewer’s eye toward him, most of the figures incline and gaze toward him. Through his handling of light, shadow, and patterning, the artist convincingly depicts a variety of textures such as those of the wood floor, the satin dress, and the metal objects. The color palette of the painting includes many neutral colors that convey a sense of the diffused afternoon sunlight, but there are also some bright colors woven into the composition, especially highly saturated reds, that help keep the viewer’s eyes moving around the scene.

To pursue his artistic career, young Moritz Oppenheim left Germany in 1820, first for Paris and then for Rome. Only a year before his departure, Frankfurt (close to his native Hanau) and several other cities were affected by the infamous “HepHep” anti-Jewish riots. The riots took place during a time of heightened political and social tension and summed up the post-Napoleonic reactionary wave. Despite enthusiastic voluntary participation of young Jews as soldiers in the German Liberation War, the post-1815 restoration of the “old order” meant for many German Jews partial withdrawal of the freedom and rights bestowed upon them during the earlier period of Enlightenment and French occupation. Caught between the often blatantly anti-Jewish German nationalistic movement opposing Jewish emancipation, on the one hand, and Jewish religious traditionalism and separateness, on the other, young liberal and acculturated Jews struggled to define for themselves a new position in a society from which they expected full recognition as equal citizens.

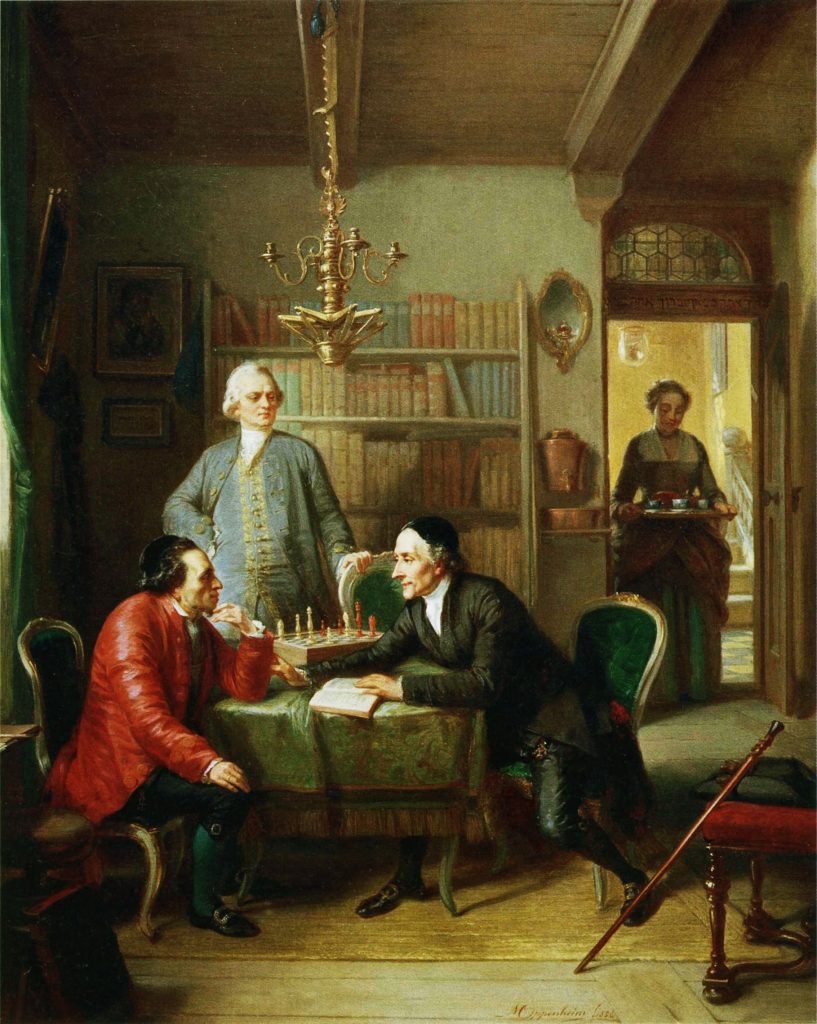

Oppenheim’s Lavater and Lessing Visit Moses Mendelssohn expands upon a thematic of confrontation and reconciliation in the political and intellectual history of German Jews.

This is an imagined meeting between scholars Moses Mendelsohn (1729-1786), Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781) and theologian Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741-1801). It is presented in Mendelssohn’s home in Berlin. Oppenheim merges two foundational moments in the history of German-Jewish cultural interactions: the real-life meetings between Mendelssohn and Lavater, which took place in 1763-64, and the subsequent unravelling of the “Lavater affair —or the failed attempt on the part of the theologian to convince Mendelssohn to embrace Christianity—and the much-celebrated friendship between Mendelssohn and Lessing, which in turn became a paradigm of the possibility of harmonious cohabitation between Germans and Jews.

Mendelssohn, wearing a bright red garment and a skull cap, is seated with Lavater at a chess table while Lessing stands at the center behind the two. Above them hangs a brass lamp (combining a Sabbath lamp, or Judenstern, with a four-branched chandelier for everyday use). A woman at right is holding a tray under a door surmounted by an inscription drawn from a Hebrew blessing: “Blessed shalt thou be when thou comest in, and blessed shalt thou be when thou goest out” (ברוך אתה בבואך וברוך אתה בצאתך; Deuteronomy 28: 6). Behind them, on the back wall at the left of the scene, hangs a mizrach (מזרח, Heb. “East,” a plaque indicating the direction being faced during prayer).

Here is a brief biography of Moses Mendelssohn

(https://ghdi.ghi- dc.org/sub_document_s.cfm?document_id=3646) :

Moses Mendelssohn achieved fame and distinction as the father of the Jewish Haskalah or Enlightenment, which entailed reconciling the Jewish religion with the broad universalist principles of the European Enlightenment. Mendelssohn pioneered Jewish engagement in non-Jewish intellectual life in Germany, embracing the philosophical project begun by Leibniz and developed thereafter by Christian Wolff. Mendelssohn remained faithful to Orthodox Judaism, but challenged Jewish traditionalism by translating the Pentateuch into German and by generally advocating the adoption of the High German language and other forms of acculturation into German society.

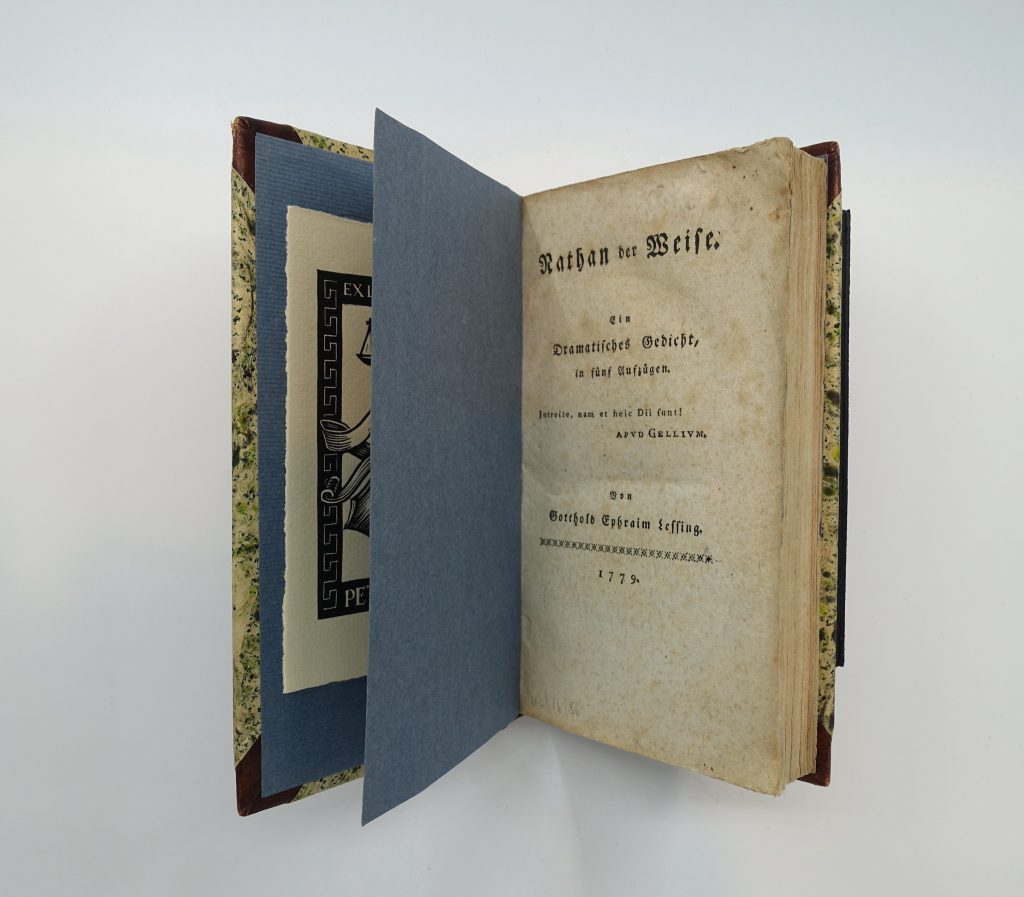

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing was a German writer, philosopher, dramatist, publicist and art critic during the Enlightenment era. Isidore Singer and M. Friedländer explain Lessing’s contribution to a positive recognition of Jews and Judaism in “Gotthold Ephraim Lessing” (the online entry in the Jewish Encyclopedia) (https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/9787-lessing-gotthold-ephraim)

Toleration and a striving after freedom of thought led him [Lessing] to condemn all positive religions in so far as they laid claim to absolute authority, and to recognize them merely as stages of historical development. A natural consequence of this principle was his sympathetic attitude toward the Jews; for he deemed it inconsistent with the dictates of religious liberty to exclude for religious reasons a whole race from the blessings of European culture.

In his comedy Die Juden, one of his earliest dramatic works, he stigmatized the dislike of the Gentiles for the followers of the Jewish religion as a stupid prejudice. He went herein further than any other apostle of toleration before or after him. The full development and final expression of his views on this problem, however, are found in his drama and last masterpiece, Nathan der Weise, Lessing thus beginning and ending his dramatic career as an advocate of the emancipation of the Jews.

…

Lessing raised Judaism in the esteem of the European nations not only by showing its close connection with Christianity, but also by demonstrating the importance of Mosaism in the general religious evolution of humanity. It was really Lessing who opened the doors of the ghetto and gave the Jews access to European culture. In a certain sense he awakened Moses Mendelssohn to the consciousness of his mission; and through Mendelssohn Lessing liberated Judaism from the most heavy chains of its own forging.

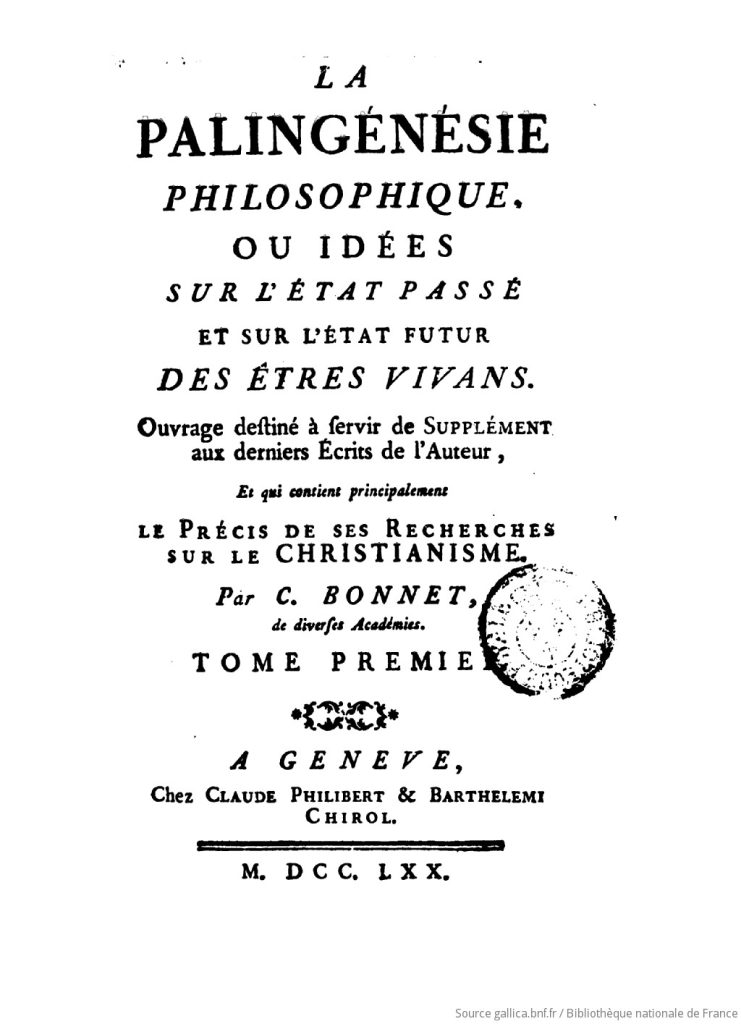

Johann Kaspar (or Caspar) Lavater was a Swiss poet, writer, philosopher, physiognomist and theologian who took Holy Orders in Zurich’s Zwinglian Church in 1789. That same year he attempted to convert Moses Mendelssohn to Christianity by sending him his translation of Charles Bonnet’s Palingénésie philosophique, a treatise on human evolution, and demanding that he either publicly refute Bonnet’s arguments or convert. Bonnet was the first to use the term evolution in a biological context. Mendelssohn refuted Bonnet and Lavater’s arguments and refused to convert.

Katharina Heyden discusses the connection between Bonnet and Lavater in “Dialogue as a Means of Religious Co-Production: Historical Perspectives” (Religions 13: 150 (2022): 1-18):

In this work, the Genevan natural scientist had presented his germ theory and from this had derived the idea that all living beings would develop and perfect themselves towards a harmony of the universe. Based on his plant experiments, Bonnet saw himself confirmed in the assumption that human beings would live on after death in a new soul–body existence, and not only in a mere spiritual way as was asserted by the philosophical doctrine of immortality. Bonnet himself, and the pietist-influenced Lavater to a much greater extent, saw in germ theory a scientific proof of the Christian belief in corporal resurrection. In his annotations to the book entitled Untersuchung der Beweise für das Christentum, Lavater had transferred the idea of germ theory to Jesus Christ as the archetype and model of the new man, to whom mankind must conform in order to contribute to the harmony of the universe.

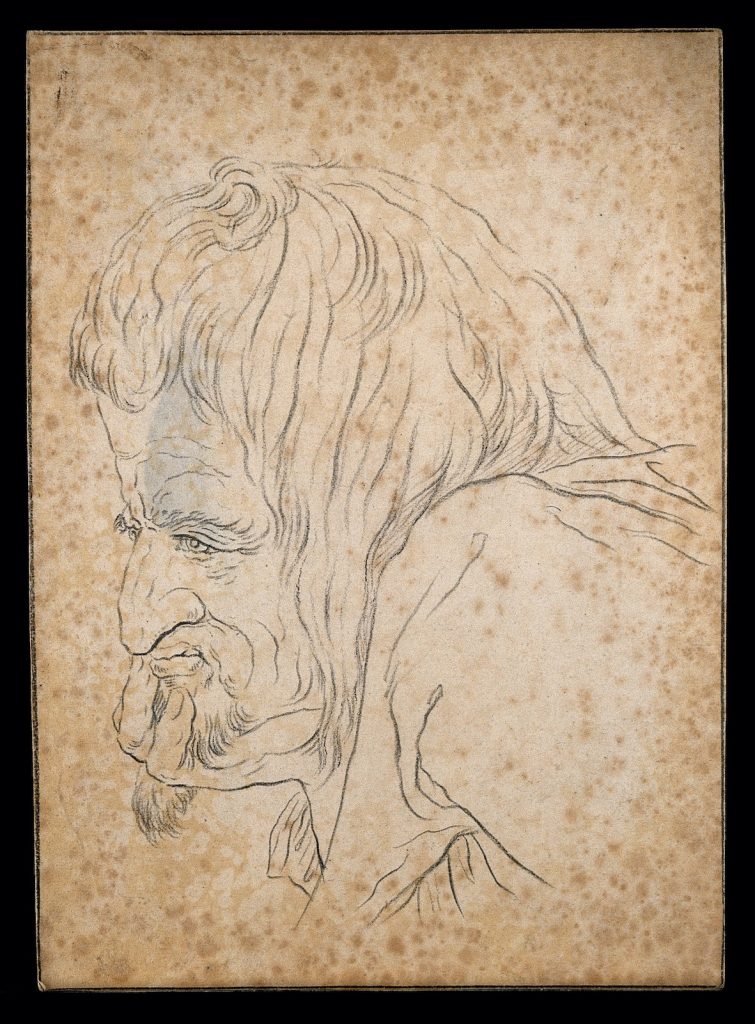

Johann Caspar Lavater’s Physiognomische Fragmente zur Beförderung der Menschenkenntnis und Menschenliebe ( published between 1775 and 1778), one of the foundational physiognomic texts of the late eighteenth century, contains his drawing of a hunched-over, hooked-nosed, and miserly looking Jew, a Judas. Lavater believed that a rejection of Christ irrevocably marked the Jewish countenance.

Lavater based his face on Hans Holbein the Younger’s characterization of Judas in The Last Supper.

Oppenheim, like the 18th-century German painter and printmaker Daniel Niklaus Chodowiecki, chose to depict Mendelssohn in profile, accentuating the so-called Jewish features that Lavater detested.

From 1865 until he died in 1882, Oppenheim focused on painting scenes of traditional Jewish life. As he wrote in his memoirs, the images reflected the world of his youth. Known collectively as Pictures of Traditional Jewish Family Life, they were redone as grisailles (painted in gray to accommodate easy reproduction), producing inexpensive mass-produced albums which found their way into almost every German Jewish home during the 19th century.

While the works may be regarded as overly sentimental, idealized images of a pious Jewish past, their value to German Jewry, whose lived experiences had been ravaged by the extreme events of the modern world, was significant. In addition, the pictures helped disseminate an iconography of domestic life that echoed middle-class German ideals of industriousness, discipline, and family values. By emphasizing these positive qualities in a romanticized view of the ghetto, Oppenheim’s Pictures of Traditional Jewish Family Life went far in tempering the negative stereotypes of the ghetto Jew. They provided Jews with a positive self-image to have and share.

The Wedding is set in the courtyard of the old synagogue in the Frankfurt ghetto. Per German Jewish custom, the bride and groom stand with their heads jointly covered with a prayer shawl (tallit) under the marriage canopy (huppah). They wear the traditional bridal belts decorated with gold that they have previously exchanged. The bride extends the index finger of her right hand to receive the wedding ring. Afterward, rather than crushing the wineglass underfoot, the groom throws it at the plaque decorated with the Star of David on the staircase. Standing in readiness for the celebration are a musician and harlequin hired to entertain.

The Frankfurt Ghetto, where Oppenheim was born, was a densely populated, squalid street. The American painter, John Trumbull, visiting Frankfurt in the 1780s, provided the following account in Autobiography, Reminiscences and Letters of John Trumbull, from 1756 to 1841(Wiley and Putnam, 1841):

The Jews’ quarter is a very narrow street, or rather lane, impassable for carriages, with the houses very lofty, old-fashioned and filthy, not more than a quarter of a mile long, – no cross avenue or alley, and a strong gate at each end, carefully closed and secured at tattoo-beat, after which no one is allowed to go out or to enter and whoever is found out of the quarter at this time is secured by the city guard and confined. This quarter is said to contain 10,000 of this miserable people; how such a number can exist in such a narrow space is almost incredible, yet here (at one of the entrance gates) I saw them crowded together in filth and wretchedness, calculated to generate disease. And how were they to escape from a fire, after the two only avenues were closed for the night? –men, women and children must be in imminent danger of perishing. The sight of such misery was most painful, and the reflection of the possible, nay probable, consequences appalling.

Oppenheim determinedly portrays the ghettos differently: as clean, warm, and comfortable. Ismar Schorsch explains the artist’s intentions in the essay “Art as Social History: Oppenheim and the German Jewish Vision of Emancipation” (in Moritz Oppenheim ( (Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Printing Enterprises, 1983). He writes, “Oppenheim’s ghettos did not loom as the embodiment of Jewish cultural inferiority, social backwardness, economic sterility, and moral depravity as contended so vehemently by the early opponents of emancipation and the Maskilim . . . Oppenheim painted the ghetto as a refuge of civility and sanctity in an uncivilized world, an oasis in which the Jew, forced to seek his livelihood in hostile terrain, returned to restore body and soul.”

The article “Moritz Oppenheim (1800-1882) and Jewish Genre Painting” (in Jewish Heritage Online Magazine, (https://www.jhom.com/arts/oppenheim/genre_painting.htm) explains the significance of Pictures of Traditional Jewish Family Life and the artist’s embrace of genre painting, artwork that depicts a scene from everyday life and which Dutch and Flemish painters transformed into a highly desirable style:

During the nineteenth century, genre painting in Europe became popular among the bourgeoisie; their tastes were conventional and they were comfortable hanging on their walls that art which presented aspects of real life to which they could relate. In the Jewish community, genre painting was especially popular among emancipated Jews.

As restrictions on Jewish activity was lifted and Jews began to live more peaceably among their gentile neighbors, many chose to leave their religious tradition and customs behind. Jewish genre art, with its depictions of Jewish celebrations and worship, provided these Jews with a reminder of their religious heritage and satisfied a craving for nostalgia. As middle-class Jews developed a growing appreciation of art — buying and putting it on their walls — they sought art with a “Jewish motif,” for lack of a Jewish painting tradition.

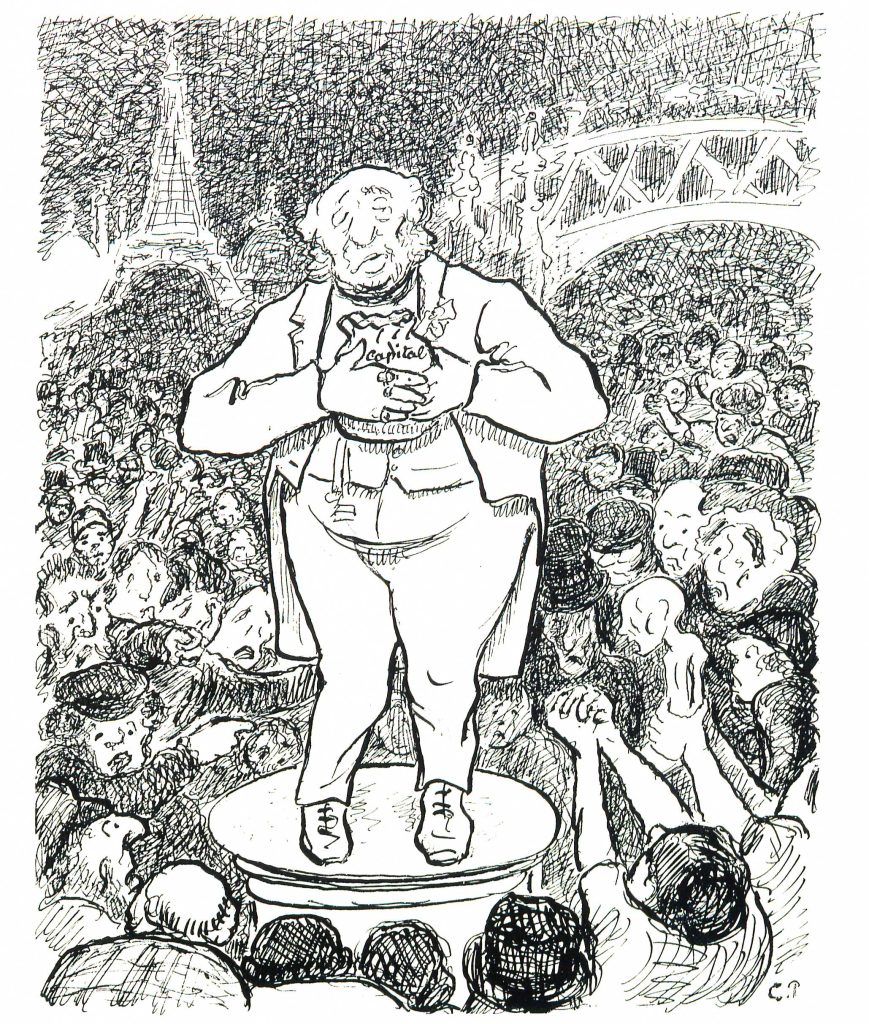

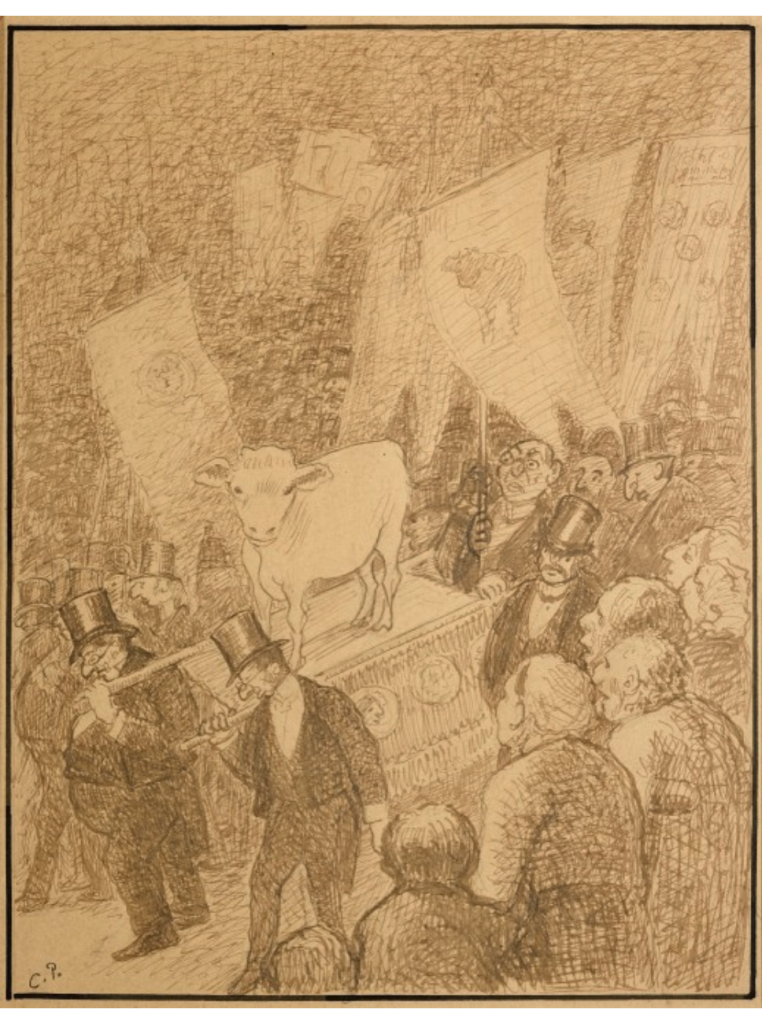

In 19th century Germany, as elsewhere, because caricatures of Jews persisted in the cultural domain, as seen in this depiction of Rothschild as a grossly fat and greedy moneylender, Jewish painters, such as Oppenheim, attempted to counteract negative stereotyping in their careful approach to portraiture and genre painting while still touching upon the struggles of the Jewish community trying to assimilate while holding on to their Jewish identities.

Sabbath Rest is a case in point. Here, a Jewish family is shown relaxing on a Shabbat afternoon. It is a placid scene, seemingly innocuous, which nonetheless conveys change. The grandmother, hair covered, reads a traditional prayer book for women, while her granddaughter reads a novel, as seen through a doorway that signifies a passage to the future. The portal is conspicuously inscribed with the date 1789, a salute to the French Revolution, which ushered in emancipation. The work underscores notions of family, morality, and literacy in an effort to combat the common stereotype that Jews were uncultured.

10.6

| Maurycy Gottlieb: Strife and Synthesis

Maurycy Gottlieb was born in Galicia in the Polish segment of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Brought up in a spirit of tolerance, the artist received a Christian education by attending a school run by the Basilian Fathers, an unusual occurrence for Jews at the time. Following his initial training at Lemberg/Lvov, he enrolled in the Vienna Art Academy, where he was a student from 1871 to 1873, his last year coinciding with the Vienna World Exhibition, the first of its kind outside Paris or London.

Filled with ambition, Gottlieb decided to leave Vienna to study at the Kraków School of Fine Arts under Jan Matejko, whom he greatly admired. However, an antisemitic incident at the hands of his student-peers shattered his aspirations and caused him to leave Kraków after less than a year. “‘Do not forget who you are and what you are,” he was threatened, “a lowly Jew, hated by all, a miserable worm, whom all have trampled on since time immemorial, and even today you can be freely humiliated without having any right to retaliate.’”

The writer Nathan Samuely recorded Gottlieb’s recollection: “When I attended the school of art my heart was filled to the brim with love of painting and my soul was overcome with all the things of beauty and loftiness that surrounded me, so much so that I believed, all too hastily, that the wall separating me from all other peoples had fallen, that the whole world was open to me, that I was a brother and friend to all mankind, that nothing distinguishes us from one another; for all of us are the sons of one father, one God has created us all.” (cited in Ezra Mendelsohn, Painting a People: Maurycy Gottlieb and Jewish Art (Hanover, NH: Brandeis University Press, 2002)

Yamina Hovav writes in “The Many Faces of Maurycy Gottlieb” (Segula: The. Jewish History Magazine 15 Feb 2017(segulamag.com)):

He studied under many first-class artists, but it was a picture by Polish master Jan Matejko that truly inspired him. Matejko’s The Fall of Poland (1866) shows the fateful meeting of the Polish sejm, or parliament, in Warsaw in 1773, in which its members acceded to the first shameful division of Poland – a prelude to the complete loss of Polish independence. Delegate Tadeusz Rejtan has thrown himself to the floor, symbolizing his country’s fall into Russian, Prussian, and Austrian hands, while other political leaders look on and the king, impatient and helpless, steps away from his throne.

The emotional power coursing through this romantic, tragic work made an indelible impression on young Maurycy Gottlieb, who even then may have found the Polish nation’s fate not unlike that of his own long-suffering people. He stood hypnotized before the painting … There and then, reversing the path trodden by most aspiring Jewish artists of his era, Gottlieb decided to leave Vienna for the relative obscurity of Galicia, studying at the Kraków School of Fine Arts under Matejko himself.

Gottlieb then went to Munich in 1875 to study under Karl von Piloty, who specialized in historical paintings. This painting by Piloty depicts the death of Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von Wallenstein (1583-1634), witnessed by Seni, his astrologer. Wallenstein, a Bohemian soldier and politician, became the supreme commander of the armies of the Habsburg Monarchy and one of the major figures of the Thirty Years War. He was assassinated at Eger in Egerland by one of the army’s officials, Walter Devereux.

Two significant influences shaped Gottlieb’s work during his stay at the Munich studio. The first was his introduction to The History of the Jews, 1853–1875, by the Jewish historian Heinrich Graetz. Graetz was the first historian to write a comprehensive history of the Jewish people from the perspective of a Jew. The eleven-volume publication, which argued for an ongoing Jewish national identity (in some ways akin to the claims for Polish nationalism), stirred the young artist to devote himself to depicting Jewish history and tradition.

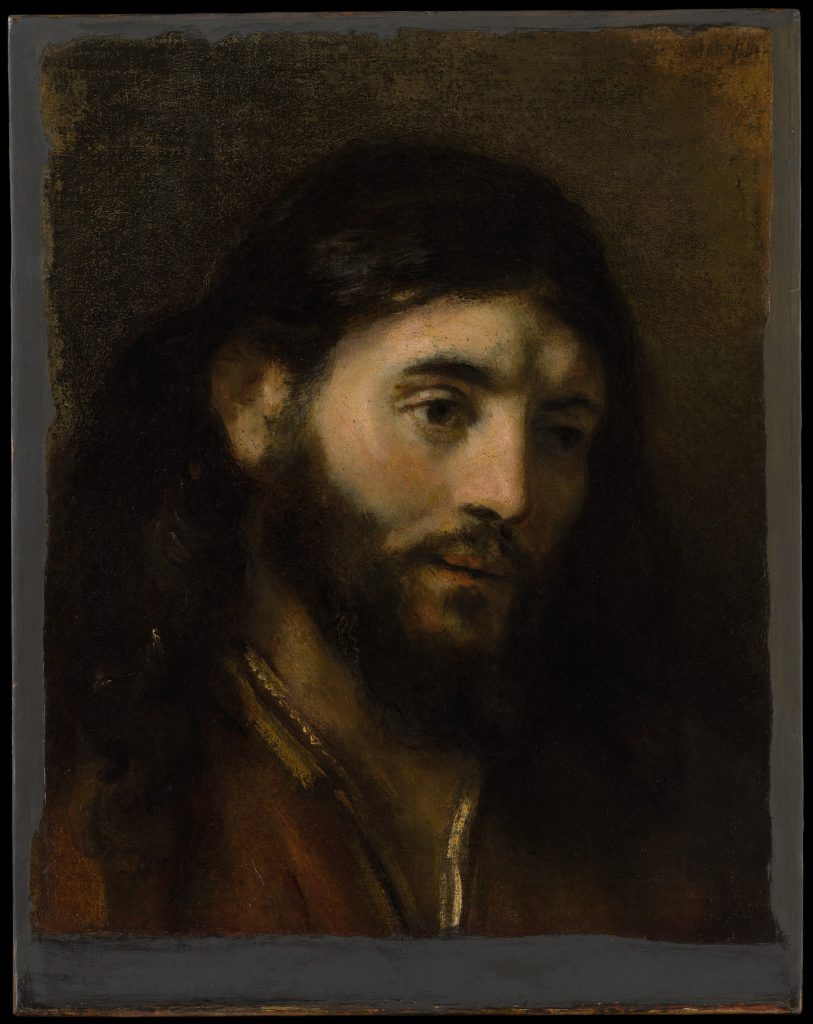

Gottlieb also became captivated by the works of the 17th-century Dutch artist Rembrandt, a Calvinist who, while not formally affiliated with any church, was obsessed with biblical subjects. Rembrandt consulted Jewish theologians regarding Old Testament imagery. His interest in Jewish physiognomy, dress, and biblical images of Christ, in particular, inspired Gottlieb to undertake themes related to Jewish history, culture and religion.

The synthesis of two separate strands of his lived experience, that of being Jewish and what it meant to be Jewish in a dominantly Christian world, as well as what it meant to be an artist in the last quarter of the 19th century, was an ongoing issue for Gottlieb. Dualities of Pole and Jew and the divide between Jewish and Christian traditions were ones he attempted to engage with by delving into historical Polish-Jewish relations or presenting Jesus as the “link” between the two religions. He saw his role as creating a new hybrid Jewish history painting in which sacred scriptures and Jewish identity could be represented to a broad, not exclusively Jewish, viewing public.

Gottlieb referenced both the Old and New Testaments in his representations. He emphasized the Jewish origins of Jesus Christ, giving him distinct Semitic features in contrast to depictions in western iconography. He reached for motifs from the Jewish-Arab world and often painted himself in ‘oriental’ costumes.

In Ahasuerus, Wandering Jew, Gottlieb portrays himself as Ahasuerus, the name usually given in German literature to the Wandering Jew, or the “eternal Jew,” a character explicitly steeped in Jewishness. Ahasuerus was a legendary figure who taunted Christ on the way to the Calvary. He was subsequently cursed and condemned to wander the world until the Second Coming at the end of time or until he acknowledged Christ as the Messiah.