Chapter Seven

PAUL GAUGUIN &

The Colonial Myth of Primitivism

CONTENTS

Introduction

7.1

7.2

Brittany and the Path to Primitivism

7.3

7.4

The Studio of the South and the Volpini Exhibition

7.5

Portraits of the Artist as Other

7.6

Savage Influences: Tahiti 1891

7.7

Fantastical Figures, Scandalous Subjects

7.8

7.9

Existential Manifesto:

Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going?

7.10

Exoticism, Eroticism, and Spirituality

7.11

INTRODUCTION

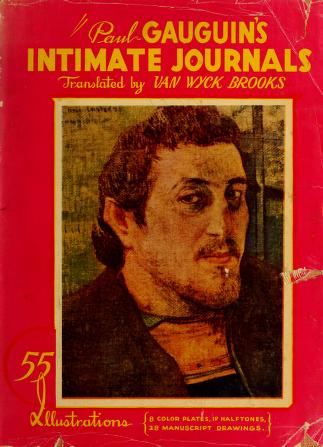

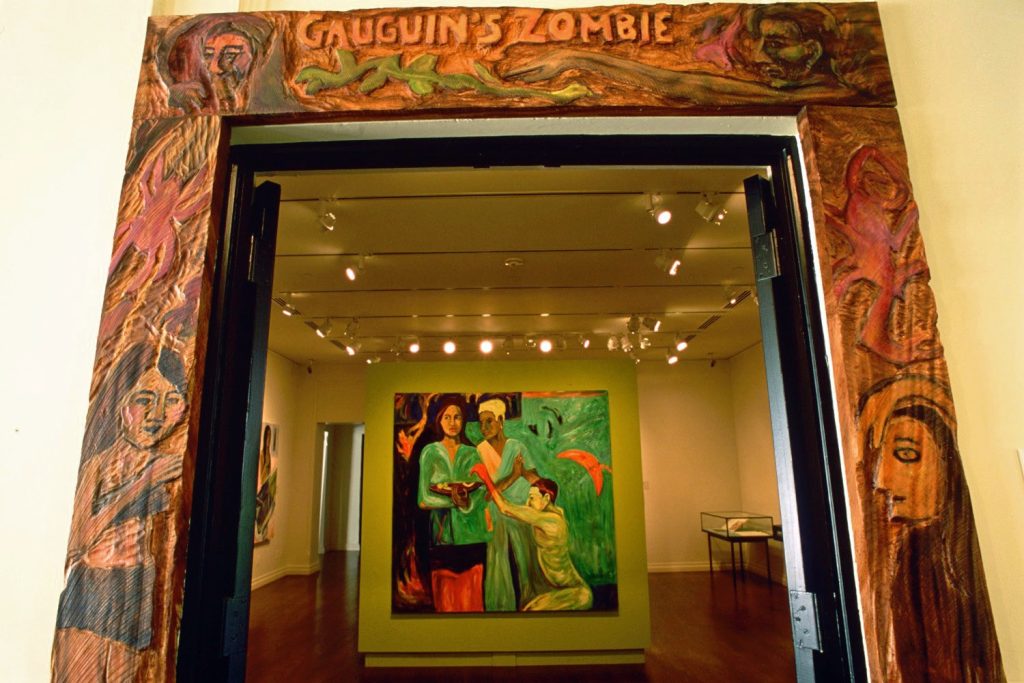

The mythology surrounding Paul Gauguin as an artist-outsider who set out to remedy the failures of western art through his sacrifice and genius was largely self-created and, for decades, perpetuated by art history itself Like all legends with a basis in fact, the myth of Gauguin, the artist has obscured the fuller context of his practice. Now viewed from a contemporary vantage point, his narrative compels reconsideration.

Gauguin created his avant-garde works by rejecting the soulless vacuum of European art to find regenerative inspiration ‘elsewhere.’ He pursued his fascination with the primitivism of distant cultures first in Brittany, then further afield in the Caribbean and the islands of Tahiti and the Marquesas. Away from Paris and the corrupting influence of civilization, he created prolifically: paintings, sculptures, prints and writings, producing works which were profoundly symbolic and technically daring. He engaged with the so-called ‘savage other’ to further his artistic vision, which he articulated in exoticized and mystical images.

While he was not the first European artist to seek foreign stimulus through world travel (Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Léon Gérôme and others had before him), he was unique in his grasping of the aesthetic and myth-making significance of primitive art. His central role in developing Symbolism derived from his interest in telling stories through simplified forms laden with meaning, his influences ranging from South Asian, Egyptian, and Oceanic iconography. His Post-Impressionism was characterized by bold outlines, vivid unnaturalistic colours and semi-abstracted forms, stylistic devices that radically influenced modern art’s parameters and perception.

However, ethical reservations now shadow Gauguin’s pioneering art legacy. His (mis)appropriation of non-western cultural traditions, his predatory sexual conduct, and his colonialist-driven sense of entitlement have spurred new critical discourse about his work across multiple disciplines, from contemporary indigenous polemics to feminist and curatorial studies.

This chapter will examine Gauguin’s art practice from a recontextualized perspective, considering ahistorical viewpoints while investigating the influences and personal ambitions of an artist who foregrounded the modernism of twentieth-century art.

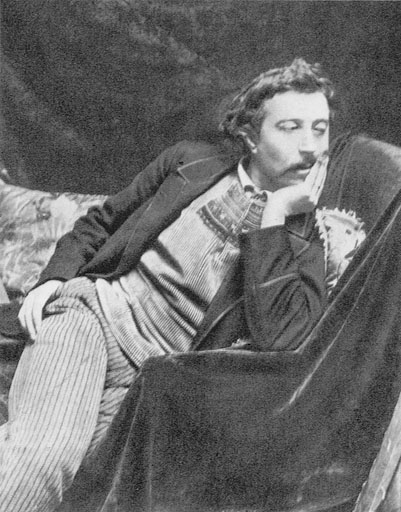

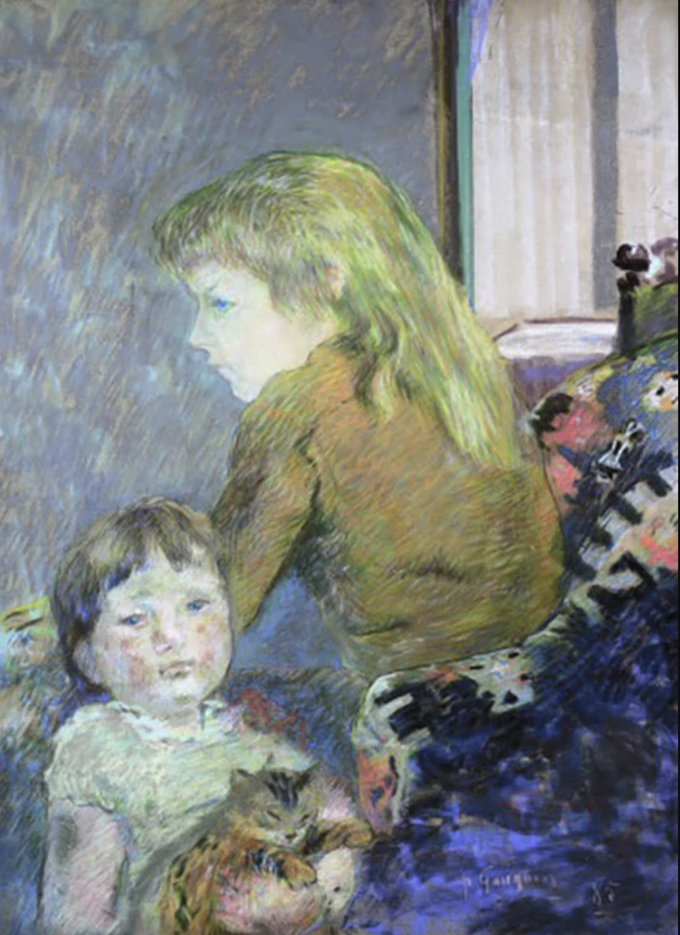

7.1

| Early Influences

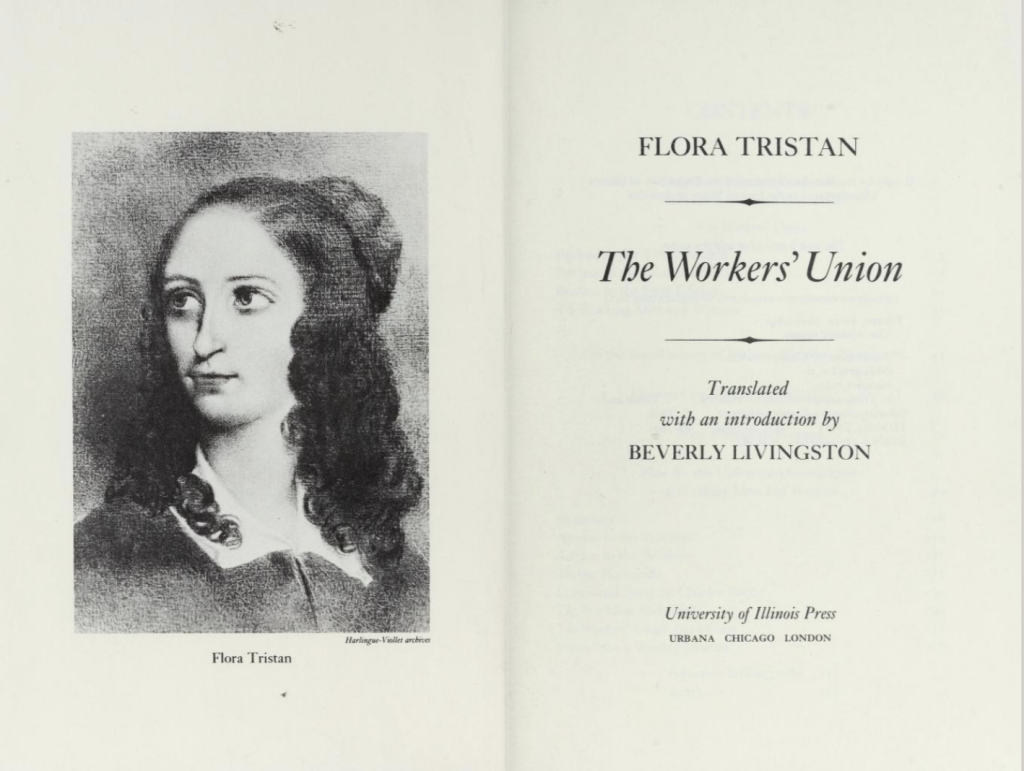

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin was born to cultured upper-middle-class parents in Paris on June 7, 1848. His father, Clovis Gauguin, was a French journalist; his mother, Aline Maria Chazal, was Franco-Spanish, and her mother, Flora Tristan (Flora Tristán y Moscoso), was a Peruvian Creole and a known socialist active in France.

Gauguin frequently referenced his “exotic” bloodline, and his family’s liberal political activism would shape his early outlook. Clovis, a radical journalist who worked for the National and was a critic of the Bonapartist regime, decided to move the family to Peru, concerned about the consequences of Napoleon III’s 1848 return to power. He died en route, but the family continued to Peru, where they stayed with relatives. In 1855 Gauguin returned to France to live with his grandfather Guillaume Gauguin, in Orléans, attending boarding school as a day student. In 1860 his mother, a dressmaker, moved her household to Paris, and her children lived with her during school breaks. She befriended the collector Gustave Arosa who became Gauguin’s legal guardian when she died. Arosa’s formidable art collection, which comprised works by Delacroix and the Impressionists, stimulated Gauguin’s nascent passion for painting.

Gauguin joined the crew of the ship Luzitano as Second Lieutenant in the merchant marine at 17, continuing the nomadic wanderings of his childhood. Six years later, he settled in Paris, working as a bookkeeper for an investment firm and marrying the Danish Mette-Sophie Gad the following year. Gauguin was increasingly drawn to the arts despite his financial stability at Bertin’s. He met Camille Pissarro at Arosa’s home and, through his connections, established himself in the Parisian art scene as a collector of art and as a ‘novice’ artist.

His early works were realistic and painterly, unlike his later style. In 1880, he made his debut in the Fifth Impressionist exhibition, but the little critical response he received was disappointing.

Gauguin was referred to as a “second-tier” Impressionist and deemed overly-influenced by Pissarro.

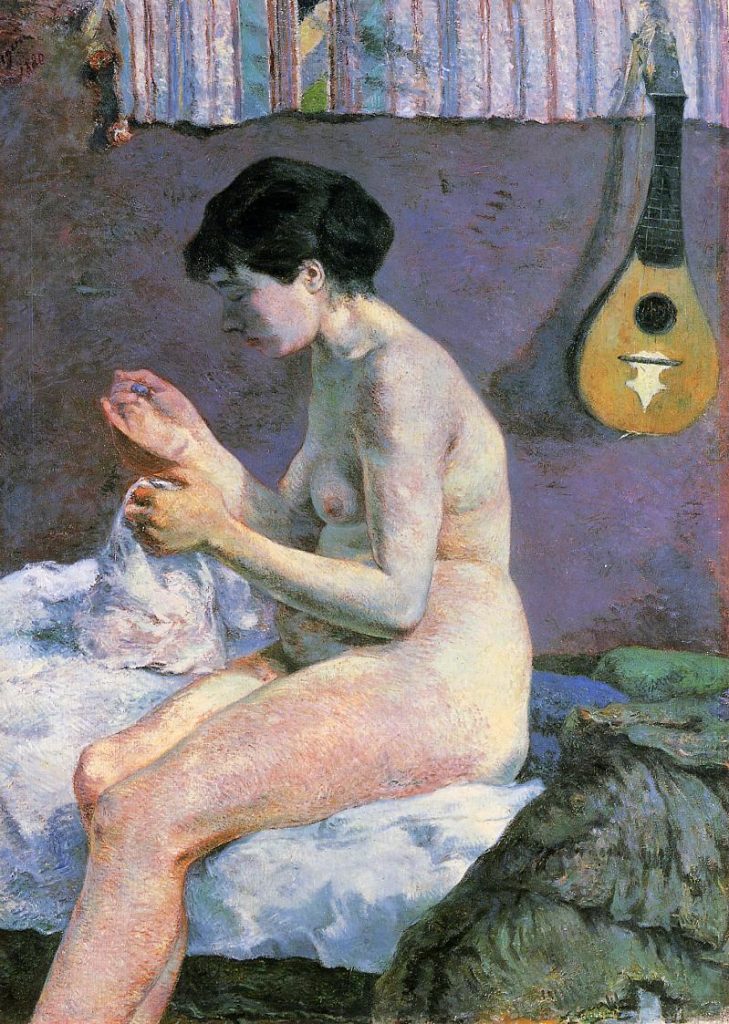

Following the stock market crash of 1882, he dedicated himself to his art, displaying eight paintings and two sculptures in the Sixth Impressionist exhibition. The works galvanized the attention of the critics.

One canvas, in particular, Nude Study (Woman Sewing) (also known as Suzanne Sewing), was praised for its direct and honest portrayal of a female nude. The female figure’s unattractive appearance made others call it cruel and horrific, but its unusual style and content established Gauguin’s aesthetic bent. According to Mary Mathews Gedo, in “Retreat from an Artistic Breakthrough: Gauguin’s ‘Nude Study (Suzanne Sewing).’” Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte 58, no. 3 (1995): 407–16):

Bertall pronounced it “the key to the exhibition,” while J. K. Huysmans lauded the artist for “representing a woman of our own time” with an unvarnished realism that none of his contemporaries could match. Only Rembrandt, declared Huysmans, transported by enthusiasm, had painted the female nude with equal honesty and directness, despite the fanciful settings in which he had represented them. None of the other reviewers responded to Gauguin’s nude study with Huysmans’ fervor, but even those who deemed the painting “cruel” or “horrific” admitted that the artist showed talent.

Gauguin continued to show with the Impressionists until their final exhibition in 1886.

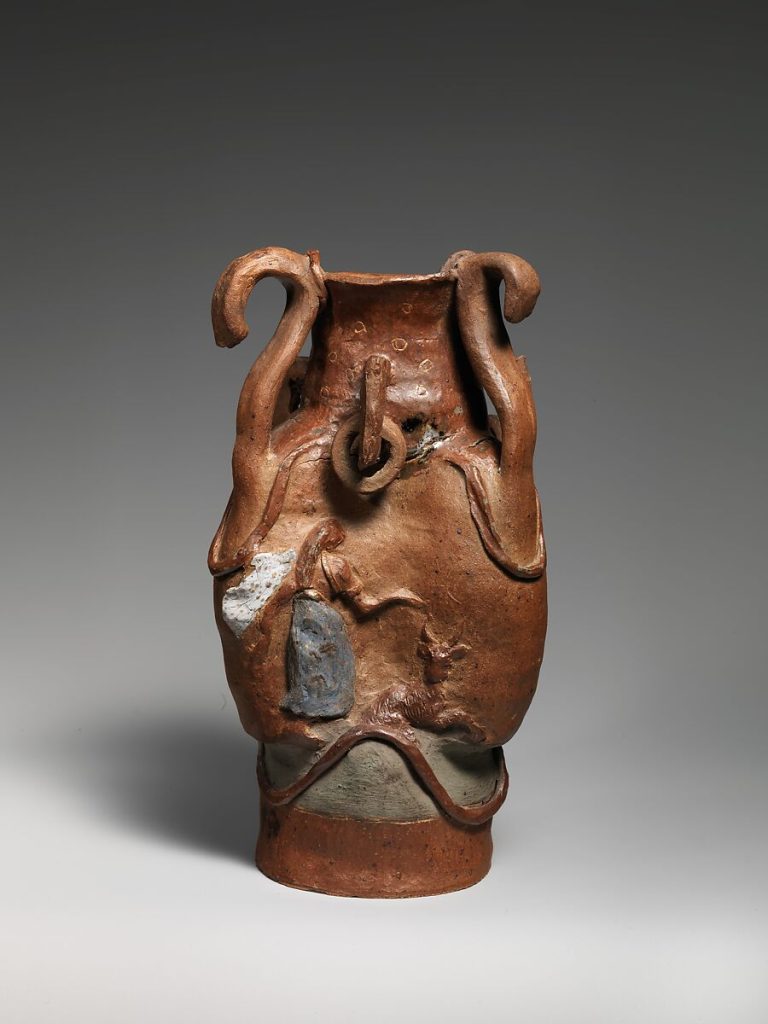

Gauguin’s sculptural interests led him to pottery-making. He worked with the ceramicist Ernest Chaplet, learning essential ceramics skills and benefiting from his collaboration on his early pieces. The medium also allowed Gauguin to develop a unique free-hand technique of working by hand without a potter’s wheel and, more importantly, to explore the expressive dimensions of sculptural ceramics through exaggerated, unconventional forms. As the Metropolitan Museum’s entry describes, the asymmetrical Vessel with Women and Goats is characterized by “un-conventional shapes and a tough ‘primitive’ appearance … Its decorative subject of a woman with a goat very likely developed during his travels in Brittany and Martinique.”

7.2

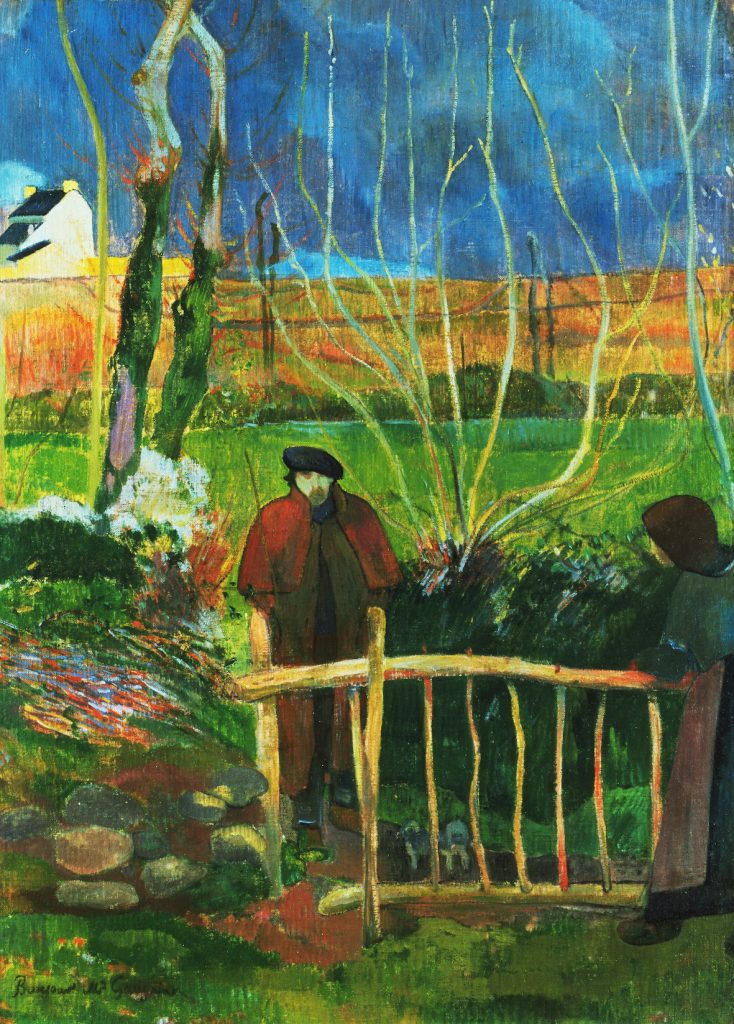

| Brittany and the Path to Primitivism

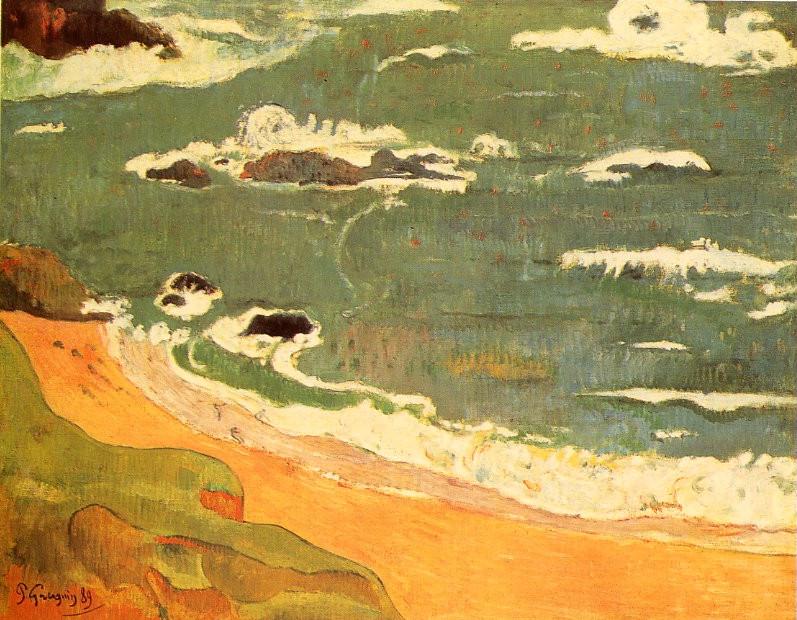

In August of 1886, Gauguin departed for the south coast of Brittany and was immediately enticed by the otherworldliness of a place where time had seemingly stood still. The simplicity and timeless traditions of the local inhabitants and the landscape— the standing stones, yellow farm fields, and wind-blown sandy beaches — conjured up the sounds and scents of the past. “I traveled back across the centuries,” he would later write, “isolating myself increasingly from my contemporaries whose preoccupation with the modern industrial world inspired in me nothing but disgust. Bit by bit, I became a man of the Middle Ages … I love Brittany; I find there the savage, the primitive. When my clogs resound on the granite soil, I hear the muffled, dull, powerful tone that I seek in my painting.”

Gauguin’s increasingly anti-empiricist and anti-naturalist art found its fit with a culture that he believed was equally resistant to the superficial rush of material progress. Gauguin’s iconic style began to take shape in this under-developed coastal province. He set out to capture the substantial elements of life in his work, turning away from the Impressionists’ stress on surface appearances towards the symbolism and subjectivity of imagery. Themes deemed primitive — peasants and their customs — were his subjects of choice.

In Brittany, Gauguin began constructing his persona of the nomadic wanderer, a familiar stranger in the local landscape. Bonjour Monsieur Gauguin was painted after a visit to the Musée Fabre in Montpellier with Vincent Van Gogh in December of 1888, where he saw the Realist painter Gustave Courbet’s Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet (1854).

There are similarities in the works. Like Courbet, Gauguin’s self-representation is central to the composition. Courbet had represented himself as a wandering figure, an artist dwelling outside the constraints of society. Likewise, Gauguin pictures himself as an eclectic outsider, the rural setting expressing his escape from civilized Paris. His figure is immersed within the landscape. Gauguin was experiencing financial difficulties at the time, and his demeanour suggests his downcast mood: pale face with a cap pulled low and a tentative stance.

On another level, the painting offers a glimpse at the interaction between the foreign artist and a local resident. The (ex)cosmopolitan Gauguin is in modern dress: greatcoat, scarf, and beret; the Breton woman is in timeless garb: heavy blue shift, a grey apron woman, and headscarf. It is a meeting of past and present, united by the sabots they both wear on their feet and the common ground they stand on. Still, they face each other across a small gate, the visual partition a symbolic compositional element often employed by Gauguin. In Brittany, among the locals, Gauguin confronted the strangeness and exoticness of the past through a culture seemingly frozen in time. The past, encountered in Brittany, was the faraway land of memory and imagination.

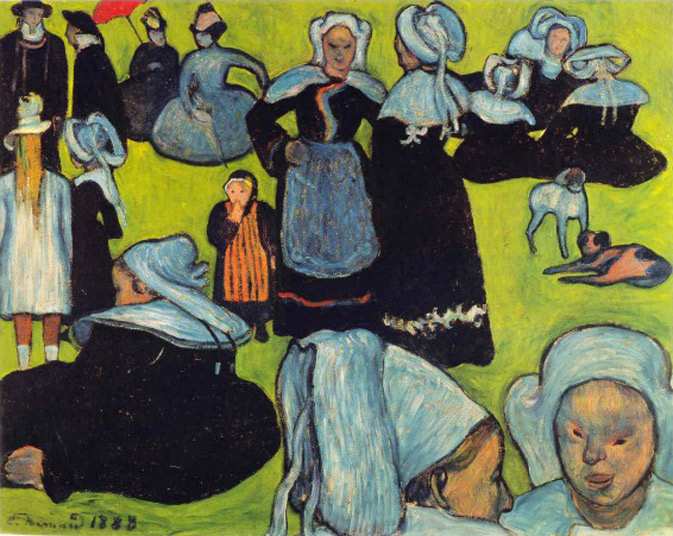

Searching for symbolic form, Gauguin found the Brittany countryside abundant with pictorial potential. The region’s roadside calvaries, the distinctive Breton costume with its vivid patterns of black and white, and its elaborate embroidered ornamentation invigorated Gauguin’s interest in flat, decorative surfaces.

Gauguin’s quest for the spiritual found inspiration also in the “primitive” Celtic Christianity of Brittany and its religious traditions. These included the ritual religious processions, called ‘pardons,’ which visibly reinforced the deep spirituality of the region. His pietist Breton paintings were highly experimental, marked by a radically unrealistic treatment of colour and space. They pointedly overlooked the infiltration of modern influences consequent to Brittany’s economic boom of the 1870s and 1880s.

The first of Gauguin’s highly personal religious subjects, Vision after the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel), encapsulates the artist’s innovative treatment of form and colour and highly inventive approach to spiritual experience. Gauguin referred to Vision after the Sermon as a “tableau religieux.”

The painting depicts a cluster of white-capped Breton women after mass, where the sermon was about Jacob wrestling with the angel (Genesis 32:24-32). What Gauguin sought to capture was not an actual event. Instead, he was manifesting a shared fantasy of faith, invisible but authentic nonetheless.

Vision after the Sermon demonstrates Gauguin’s marked move away from the Impressionists’ emphasis on the visible, sensory world to narratives drawn from the psyche, which he articulated in a distilled, direct manner. In the painting, the real and unreal spaces are divided by the curve of a tree bough. The stylized female figures are placed on one side of the cleaved composition, while on the other, two much smaller male figures wrestle on a blood-red ground.

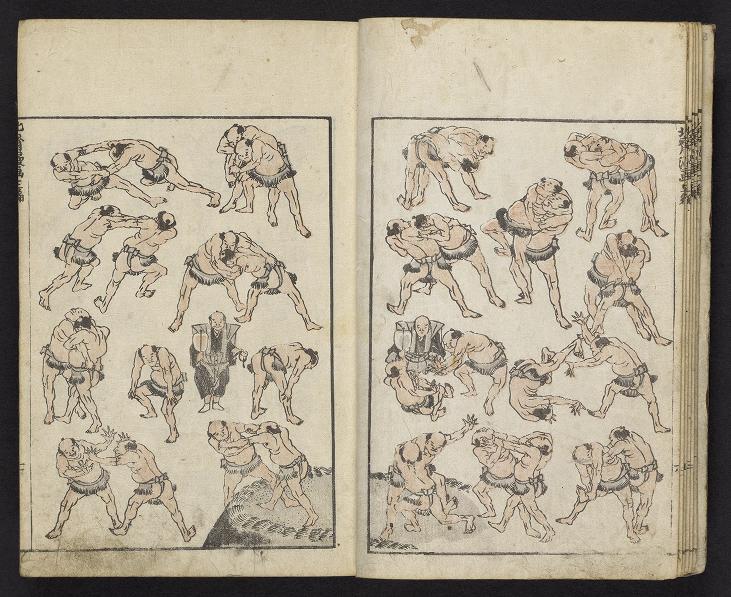

The male figures appear to be inspired by images of Hokusai wrestlers, furthering the notion that the painting’s religious narrative is covert, and thus a presumption of faith on the viewer’s part.

Writing in a letter to van Gogh in 1888, Gauguin expressed his awareness of the radicality of the work,

Grouped Breton women, praying, very intense black dress – very luminous yellow white hats. The two hats on the right are like freakish helmets – an apple tree traverses the canvas, dark purple, and the foliage is drawn in masses like emerald green clouds with sunny yellow-green interstices. Ground pure vermilion. At the church it declines and becomes red brown. The angel is dressed in strong ultramarine and Jacob in bottle green. Angel wings pure chrome yellow no. 1 – Angel’s hair chrom no. 2 and feet orange flesh – in the figures I think I’ve attained great simplicity, rustic and superstitious – all very severe – The cow underneath the tree, tiny compared to reality, is bucking – For me, the landscape and wrestling match in this picture exist only in the minds of the people praying after the sermon, that’s why there’s a contrast between the natural people and the wrestling match in a non-natural, disproportionate landscape.” (cited in Rodolphe Rapetti, Symbolism, Deke Dusinberre, trans. (Paris: Flammarion, 2006), 108-9)

Vision after the Sermon stands as Gauguin’s first intentionally Symbolist painting. Here, all the elements of Synthetism are in evidence. As Nicole Myers writes in “Symbolism” (Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 2007 http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/symb/hd_symb.htm), Gauguin and Bernard aimed to “synthesize abstracted form with emotional or spiritual experience. Here, Gauguin combined heavily outlined, simplified shapes with solid patches of vivid color to symbolically express the ardent piety of simple Breton women.”

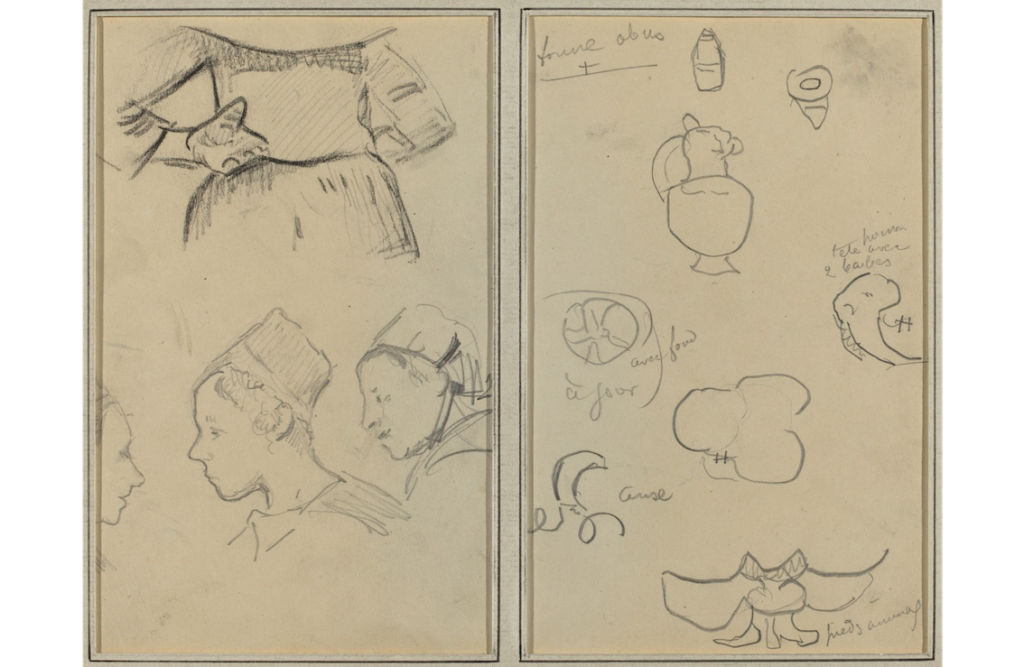

Despite Gauguin’s formal simplification of the figures, his working methods were not simplistic or naive. He selected his images carefully, methodically creating motifs which he employed in various arrangements.

Claire Bernardi, writing about Four Breton Women in “Iteration and Invention in Gauguin’s Paintings” (in Gauguin: Artist as Alchemist, edited by Gloria Groom, 56–63 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017)).

[His] working method is clearly visible in the preparation of many of his works in two dimensions and also in his unique habit of transferring a motif from one work to another. The artist created his canvases in stages, especially the more ambitious and carefully planned compositions of the mid-1880s. The preparatory drawings – either made from life or a model-have survived for a number of works, including Four Breton Women. They allow us to ascertain the different means he employed to transfer an image from drawing to a painting. This canvas, which represents the artist’s ambition to create a composition that emphasized the dialogue between its figures, was probably created in Gauguin’s studio upon his return to Paris in mid-October 1886.

Gauguin’s sketchbooks illustrate the way in which the artist reworked older studies to use as preparatory sketches for his canvases. As quoted in Bernardi, Gauguin shared his methodical process in a letter to his friend Georges-Daniel de Monfreid in 1892: “I am going to let you into a secret. There is a great deal of logic in it, and I act methodically…the methodical way is to arrange matters so that things follow smoothly… If only people did not spend so much time in useless and unrelated work! One stitch a day-that’s the great point…” His statement recalls one he had made three years earlier to Emily Bernard in which he suggested that continuous repetition and reinterpretation were key ingredients of his aesthetic; “I experience pleasure not at going further than what I previously prepared. But at finding something more.”

David Clarke, in “Gauguin, Linguistic Opacity, and Cultural Difference” (Source 38, no. 2 (2019): 98–107), asserts that Gauguin’s images of Brittany and later Tahiti speak to colonial power and subjugation. France forced its language and cultural values on these local populations, primarily by suppressing their traditional languages. Clarke examines how the encounter with linguistic otherness is handled in the painting of Gauguin, arguing that it is an underappreciated theme of his art.

Clarke contends that Gauguin may have addressed linguistic issues and the impenetrability of cultural otherness in some of his works, such as Four Breton Women of 1886. Its depiction of an isolated group of women conversing in the Celtic Brittonic language speaks to exclusion (Gauguin’s as well as the viewers). It may point to the artist’s initial feelings of alienation. The depiction of the women with their backs and eyes turned away signals that difference. Clarke points out that Gauguin’s feelings of linguistic isolation after his arrival at Pont-Aven can be documented by his letter to Mette in July 1886, in which he notes, “there are hardly any French people here.”

Humphrey Lloyd Humphreys estimates that there were 1,320,000 Breton speakers in 1886 (the year of Gauguin’s painting), of which 51 percent spoke only Breton. Only 5 percent of the residents of Brittany at that time spoke French alone. He also notes that “knowledge of French spread earlier among men than among women” (a fact relevant to the consideration of Gauguin’s painting, which features only female subjects), and places the habitually or exclusively French-speaking population as “a small upper-and middle-class minority with noticeable concentrations restricted to towns and households of the landed aristocracy.” He believes that lower Brittany (where Gauguin was based) was largely populated at that time by people who spoke only Breton.

In surreptitiously addressing the linguistic divide, Gauguin would have been engaging in an ongoing problem. Mandatory secular education had just been enacted by Jules Ferry. As Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 1881 and 1883 to 1885. Ferry promoted excluding the Catholic Church from the public domain and colonial expansion. In Brittany, these reforms meant that the Breton language could no longer be spoken in classrooms, with consequences for defiant teachers and pupils alike. Ironically, the little protection the Breton language had, was under the umbrella of the Catholic church.

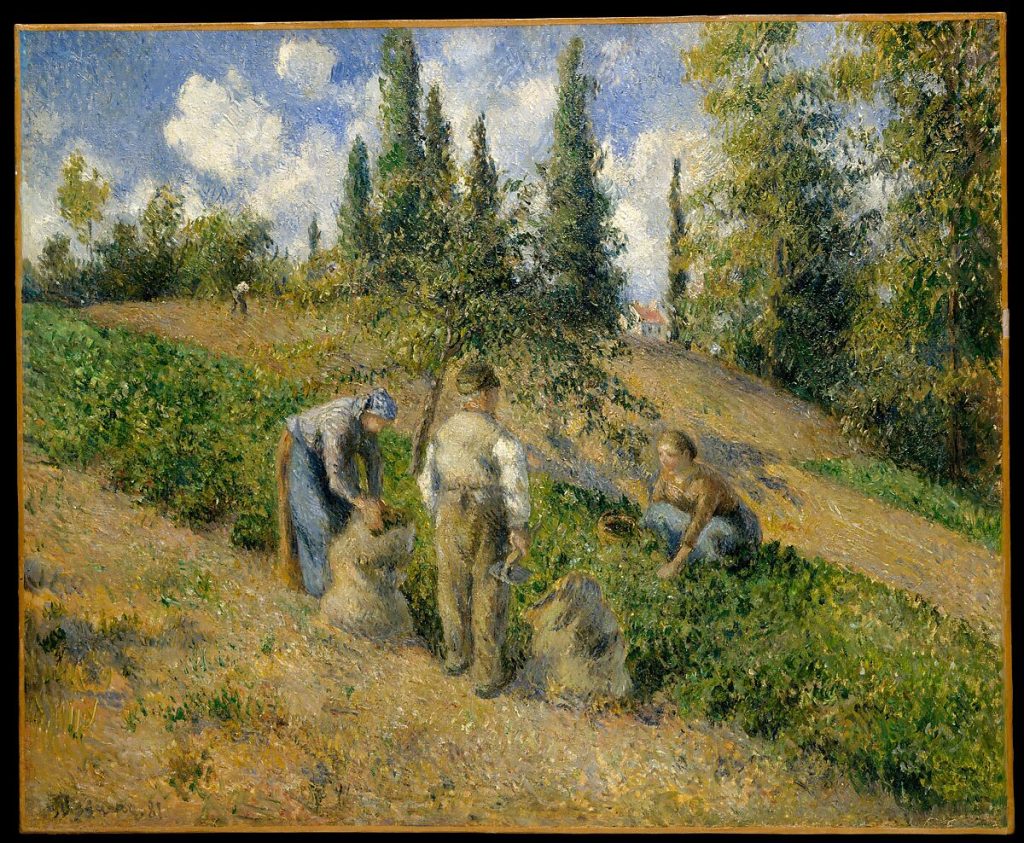

Gauguin’s subjective conceptions of reality were anathema to contemporaries such as Pissarro. As a committed anarchist, Pissarro believed that art that diverted attention from real-world events or authentic appearances was pure escapism. On May 14, 1891 he wrote to his son Lucien, singling out Gauguin as a prime example of the misguided mysticism of new art trends. (John Rewald, ed., Camille Pissarro: Letters to his Son Lucien, 170-171 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1943)):

De Bellio confessed to me that he had changed his view of Gauguin’s work that he now considered him a great talent. Why? It’s a sign of the times, my dear. The bourgeoisie, astonished by the immense clamour of the disinherited masses feels it necessary to restore to the people their superstitious beliefs. Hence the bustlings of religious symbolists, religious socialists, idealist art, occultism, Buddhism etc. etc. Gauguin has sensed this tendency. The Impressionists have the true position, they stand for robust art based on sensation, and that is an honest stand.

Paul Cezanne’s planar designs were also in marked contrast to the expressive, emotional vocabulary of Gauguin.

7.3

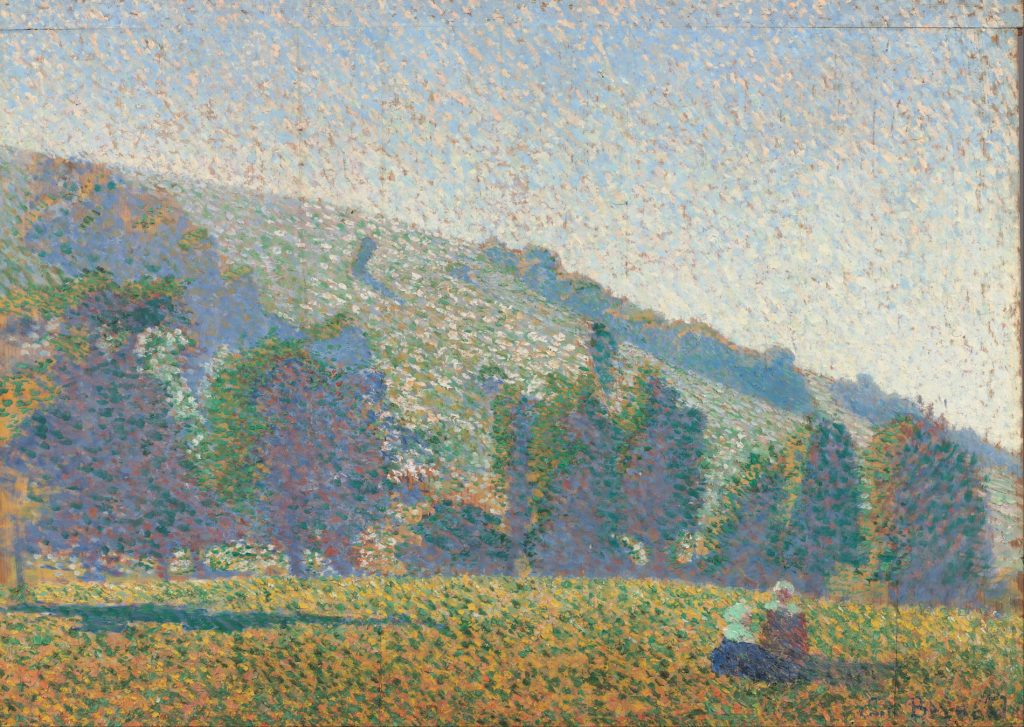

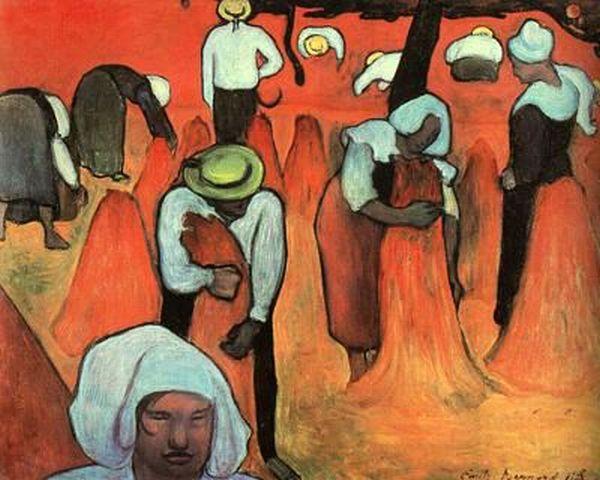

| Émile Bernard and Synthetism

Émile Bernard had come to Brittany in the Spring of 1886, before Gauguin’s first visit. His career was short-lived but prolific, and his work influenced the direction of modern art in its radical treatment of form and colour. Before his sojourn on the French coast, he had studied in the studio of the academic painter Fernand Cormon.

In 1886, at 18, Bernard was expelled from Cormon’s studio for his lack of discipline and for his experimental style. He went to Brittany to paint, meeting Gauguin four months later at the Pension Gloanec.

In 1887, according to Ronald Alley in “Émile Bernard: Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum” (Burlington Magazine 133, no. 1056 (1991): 214–16): Gauguin’s objective was “to create a visual equivalent to literary Symbolism… [he] began to develop a style inspired by Japanese prints and stained glass, with flat areas of colour surrounded by bold outlines… [by this time] he had become very friendly with Van Gogh.”

Returning to Brittany again in 1888, Bernard joined up with Gauguin at Pont-Aven where, as Alley states, Bernard “according to his own account had a decisive influence on Gauguin’s style, his picture of Breton women in the meadow prompting Gauguin to paint Vision of the Sermon and make a complete break with Impressionism.”

Two decades apart in age, Gauguin and Bernard desired to simplify form and intensify colour to express the essence of their subjects best. They called their art Synthetism, a term they preferred to Cloisonnism, coined by art critic Édouard Dujardin on the occasion of the Salon des Indépendants in March 1888, where Bernard and Gauguin’s works were on exhibit. In both, the decorative outlines derive from the enamel cloisonneé technique and recall the flat distilled images of Japanese prints.

Bernard and Gauguin continued to work together until February 1891, but the ongoing argument about which one was the originator of Synthetism led to their final rift. Bernard left France in 1893, living abroad for over a decade, mainly in Cairo.

Alley states, “He turned against modern art and became a devout Catholic and politically very right wing. Nevertheless, he continued up to his death in 1941 to insist on the importance of his own role as a pioneer of Symbolism in painting, and wrote various articles of a rather bitter, polemical kind to justify his claim.”

The schematized brilliance of Synthetism was conducive to the depiction of charged spiritual subjects and Gauguin’s intensifying interest in the symbolism of the Passion. The Yellow Christ, a radical interpretation of the Crucifixion scene, exemplifies Gauguin’s abandoning naturalistic observation for expressive colour and form. Jesus is painted in bright yellow and is placed in a landscape of orange trees and saffron hills. Christ has Gauguin’s face, and the Breton women surrounding him are in contemporary costumes, melding present and past.

Gauguin’s landscapes are filled with artifice, the awkwardly interlocking of foreground, middle ground and background creating an arbitrary space. The events are neither historical nor completely contemporary, and the scenes are neither completely familiar nor imaginary, anticipating the full-blown ambiguity of the artist’s later mythical work.

The Green Christ led the poet, art critic and painter Albert Aurier to dub Gauguin a as synthetist ideist, or symbolist, shortly after it was painted. He declared:

[N]ow that we are witnessing the agony of naturalism in literature and, simultaneously, the preparation of an idealist, even mystical, reaction, we should wonder whether the plastic arts are revealing a similar evolution. The Struggle of Jacob and the Angel, which I have attempted to describe by way of an introduction, is sufficient proof that this tendency exists, and one must understand why painters treading this new path reject this absurd label of impressionist, which implies a program diametrically opposed to theirs. This little discussion about words – which might appear ridiculous at first – is nevertheless, I believe, necessary, for everyone knows that the public, supreme judge in artistic matters, has the incurable habit of judging things according to their names. One must, therefore, invent a new term ending in ist…for the newcomers whose leader is Gauguin: synthetists, ideists, symbolists, as one likes best…” (G.-Albert Aurier, “Le Symbolisme en peinture: Paul Gauguin,” Mercure de France, no. 2 (March 1981); cited in Henri Dorra, Symbolist Art Theories: A Critical Anthology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 197)

7.4

| The Studio of the South and the Volpini Exhibition

Gauguin traveled to Arles in October 1888, where he and van Gogh had established a joint residence, a “studio of the South.” The idea for a “studio of the Tropics” took root soon after. In a letter to Bernard, Gauguin talked of his plan to travel to the Indian Ocean Island of Madagascar to establish a new studio, a plan he had also shared with van Gogh. In his letter, he advised Bernard that “the future of a new generation [of artists] in the tropics seems absolutely right,” and van Gogh agreed, writing that “new art will have the tropics for its homeland.”

Gauguin and van Gogh imagined they would live cheaply, bask in the sun, and attract beautiful women as models and lovers in their ambitions to produce avant-garde work. Their romanticized vision was informed by a host of sources, both factual and fictive. For Gauguin, they stemmed from his childhood experiences in Lima, Peru, and his travels as a merchant marine in Europe, the Americas and the Pacific, including Bergen in Norway, Iquique in Peru and Auckland in New Zealand.

The dream of a Tropical studio was never realized. On Christmas Eve, two months after Gauguin’s arrival in Arles, a severe quarrel between the two resulted in Gauguin’s departure. It was the last time they saw each other.

Gauguin spent the first three months of 1889 in Paris. That year the city hosted the Exposition Universelle, the world’s fair, showcasing the latest in technology and art from over thirty-five countries. France was represented by the creme de la creme of its academic artists. Gauguin and other progressives were not included. Knowing of their rejection, they cast about for a venue to exhibit their works in a city swarming with potential buyers. L’Exposition de Peintures du Groupe Impressioniste et Synthetiste (the Volpini Exhibition) was held at the Café des Arts on the Champ de Mars, near the Exposition pavilion and the new Eiffel Tower that marked the entrance to the exposition.

The exposition included a Wild West show.

Nancy Mowll Mathews examines how Gauguin absorbed Buffalo Bill’s dual cowboy and Indian mythologies at Neuilly-sur-Seine in “Gauguin, Buffalo Bill, and the Cowboy Hat” (Transatlantica: Revue d’études américaines / America Studies Journal (https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/10968?lang=en):

Gauguin brought to the Wild West … his own recently-constructed identity as an American Indian (albeit Peruvian) and, in the years following—while in Brittany, Tahiti, and Paris—performed various aspects of the French interpretation of ‘Buffalo Bill’ as applied to a pioneering modern artist. Gauguin’s New World context was extensive, and included his Peruvian and other South American relatives, his art world audience of American artists and collectors, and, finally, his expatriation to the Pacific islands of Tahiti and the Marquesas. His adoption of the long hair and cowboy hat, made internationally famous by Buffalo Bill, gives us a key to understanding how he wove together the French and American cultural notions of primitivism, sexuality, leadership, and the avant-garde. And in turn it sheds new light on Buffalo Bill himself as we see him through the lens of the French avant-garde art community. In Gauguin’s interpretation of both Buffalo Bill’s gender performativity and of the avant-garde scout, we gain a new appreciation of [Buffalo Bill] Cody’s daring embrace of androgyny and rejection of the narrowness of western civilization, all of which makes him more ‘modernist’ than the twentieth-century cowboy mythology has previously led us to believe.

Roger Cardinal in “Gauguin” (Burlington Magazine 152, no. 1293 (2010): 805–8), a review of the exhibition Gauguin: Maker of Myth at Tate Modern in 2010, discusses Gauguin’s storytelling and self-inventions as put forward by exhibition curator Belinda Thomson.

Paul Gauguin needed to be noticed, and constructed a mythic version of himself which embraced both the striking elements of his biography as a social outsider and exile, and the styles and themes of his art, where he stood out as a pioneer of novel expression.…

Central to Gauguin’s Tahitian narrative was the persona of the European adventurer who had ‘gone native’ and made a string of dusky conquests.

7.5

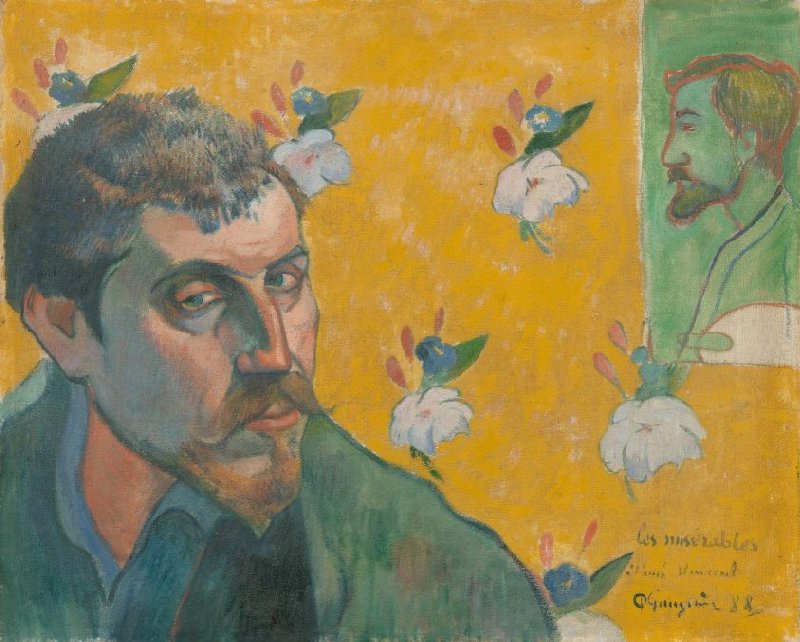

| Portraits of the Artist as Other

Despite Gauguin’s expectations, the Volpini exhibition was a commercial failure. Receiving the news back in Brittany, he fell into despair. As Jaworska Władysława describes in “‘Christ in the Garden of Olive-Trees’ by Gauguin. The Sacred or the Profane?” (Artibus et Historiae 19, no. 37 (1998): 77–102):

His failure was even more painful as it put off his longed-for “departure for the tropics.” He complained in a letter to Emil Schuffenecker: “I am climbing the hard road of Golgotha. Sounds of outcries, which my latest pictures triggered me from Paris. I do not want to say that they are good, but that they lead to something more perfect than my latest paintings.” He also described his state of mind in a letter to Emil Bernard: “The news I get from Paris discourages me so much that I lack the courage to paint and I drag my old body exposed to the northern wind, along the sea shore in Le Pouldu. Automatically I make a few studies (if one can call studies these few strokes of brush coordinated with the eye). But my soul is far away and looks sadly into a black abyss that opens in front of me.”

Christ on the Mount of Olives is a dark and profoundly evocative self-image. Extending his time in Brittany, Gauguin continued to paint a series of self-portraits relating himself to the suffering of Christ and building his self-mythology as a hero and martyr. Later, he told a journalist, “There I have painted my own portrait… But it also represents the crushing of an ideal and a pain that is both divine and human.”

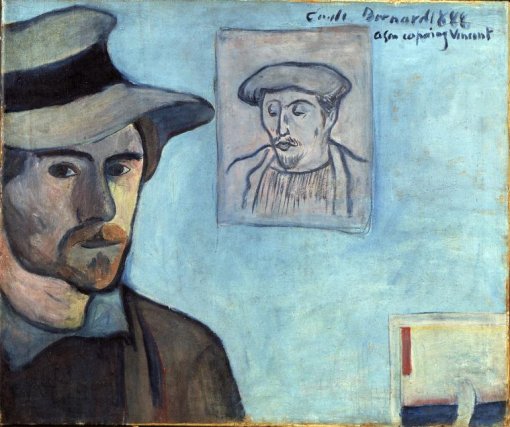

There is an affinity with his earlier self-images of suffering, for instance, the self-portrait entitled Les Miserables, which was painted for Van Gogh the year before.

Emily Browne, a contributor to Sartle: Rogue Art History, a blog that “mixes serious art history with snarky observations,” writes (https://www.sartle.com/artwork/self-portrait-with-portrait-of-Émile-bernard-paul-gauguin):

Gauguin did something a little funky with his self-portrait though. He made himself look like Jean Valjean, a character in Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables, to insinuate that he is an outcast, but also the best of society. The character Jean Valjean is an ex-con who was imprisoned for stealing bread for his sister’s starving children. So, in this painting Gauguin is hinting at the fact that he and his little collective were the good guys and were breaking the rules in order to do the right thing…as opposed to those miscreants in Paris.

The colors in the piece, at least for the time period in which it was made, are gaudy. Gauguin’s guava-colored face contrasts harshly with the green portrait of Bernard (done by Bernard himself). The unsettling yellow of the background wallpaper features flowers that are supposed to indicate their “artistic virginity.” They were definitely working outside of the box, which made their geographic location outside of Paris all the more fitting.

Władysława continues, “His suffering is so heart-rendering that it can only be compared to the suffering of Christ… This is not a portrait painted from a mirror likeness. The closed eyes with the heavy eye-lids, the large distinct “broken” nose (which was meant to confirm his Inca origin), the shape of his chin were all treated summarily as an archetype to be often repeated in his self-portraits whether en face, profile or trois quarts views.”

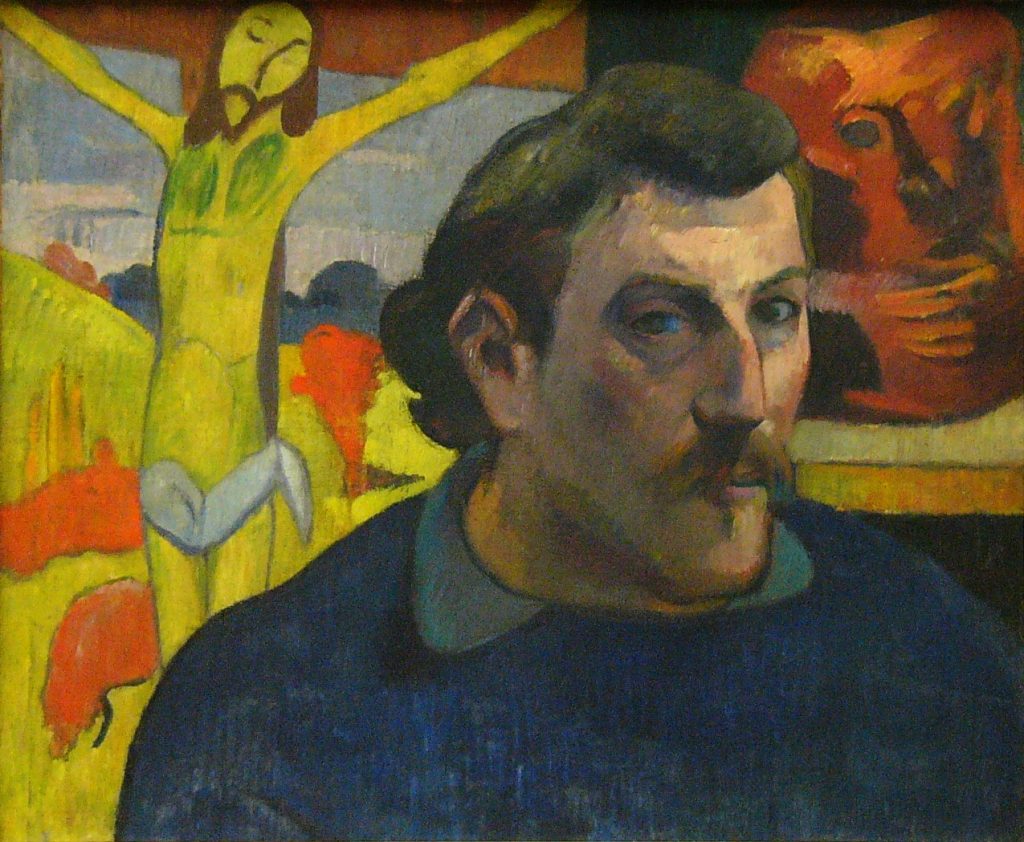

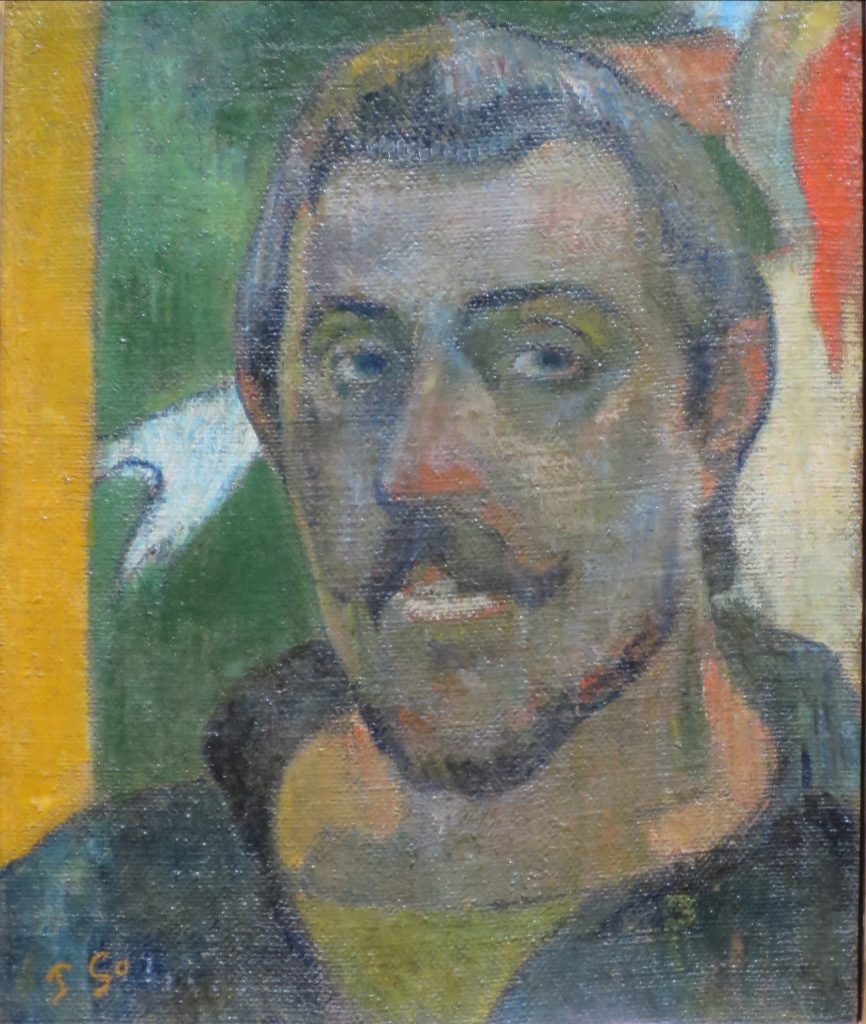

In 1891, on the eve of his first trip to Tahiti, Gauguin painted his portrait manifesto, Portrait of the Artist with the Yellow Christ, where the Crucifixion scene occupies more than half the background surface. A large earthenware tobacco pot molded in the artist’s likeness hovers behind him. His self-image looms large in the foreground, a brooding, confrontational presence whose burdens and determination stare us in the face.

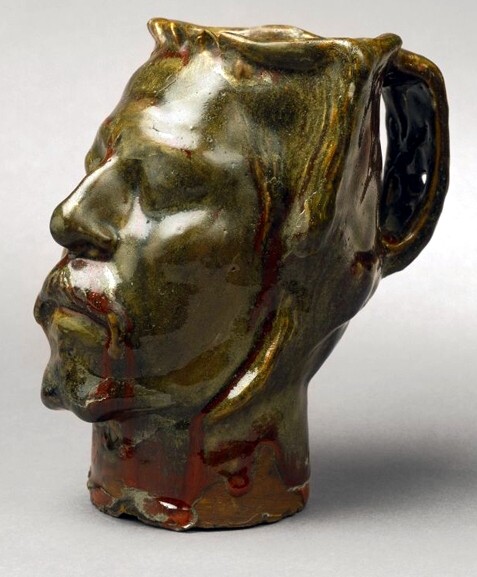

Gauguin’s Jug in the Form of a Head is, in essence, a severed head. The streaming red against the glaze of the ceramic surface suggests the blood of injury and suffering. The crude subject is furthered by references to the exotic Peruvian folk pottery he would have seen in Paris.

In another self-portrait of the same era, Gauguin seems again to accentuate his exotic heritage; part of his self-fabrication was his claim to be of Inca descent. This is apparent in the dark skin and Peruvian-like features. While the narrative is limited in accuracy, Gauguin employed it to mythologize his otherness, stating, “You know I have Indian blood, Inca blood in me, and it’s reflected in everything I do….”

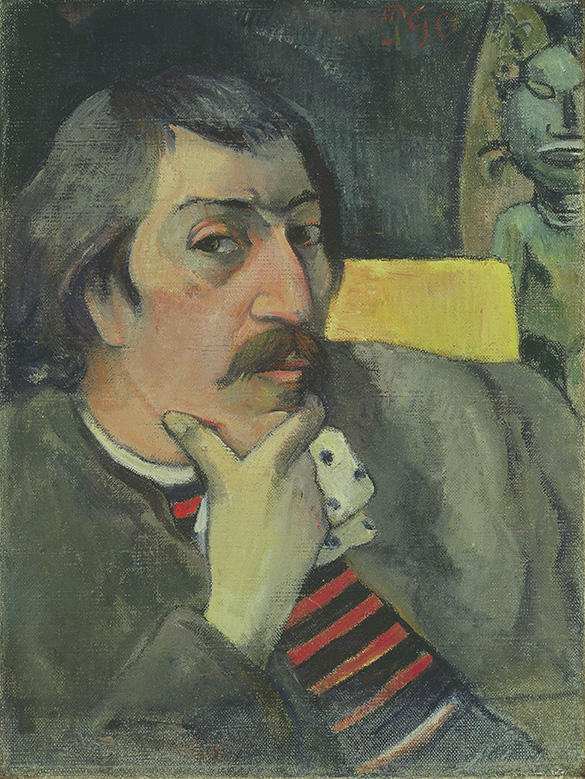

Two years after painting Self-Portrait with the Yellow Christ, Gauguin painted a self-portrait with a Maori deity in the background, an indicator of the mixing of myths he was prone to. Self-portrait with the Idol was completed towards the end of his first Polynesian stay. Chin in hand, looking directly at the viewer, Gauguin is pensive and composed, the idol a representation of the goddess Hina, who symbolized happiness, calm and peace.

In 1890, Gauguin was staying in the remote village of Le Pouldu. He continued to sell through the Parisian art dealer Theo van Gogh, but his sales declined.

Vincent Van Gogh died in 1890, followed by Theo six months later. By this time, Gauguin no longer found inspiration in Brittany, finally understanding that it was not a place forgotten by time, even as he claimed otherwise in letters to family and friends. The unique local costumes were not vestiges of an ancient pagan past, and the ‘pardons’ were as much intended to attract tourists as they were public expressions of religious faith. The exoticism he sought in Brittany did not exist.

7.6

| ‘Savage’ Influences: Tahiti, 1891

Gauguin remained in Le Pouldu until his transfer to the Pacific Islands as head of a government-funded artistic mission in 1891. He confided in a journalist from the Écho de Paris: “I am leaving to be at peace, to be rid of the influence of civilization. I only want to do simple, very simple art. For that, I need to re-immerse myself in virgin nature, to see only savages, to live their life.”

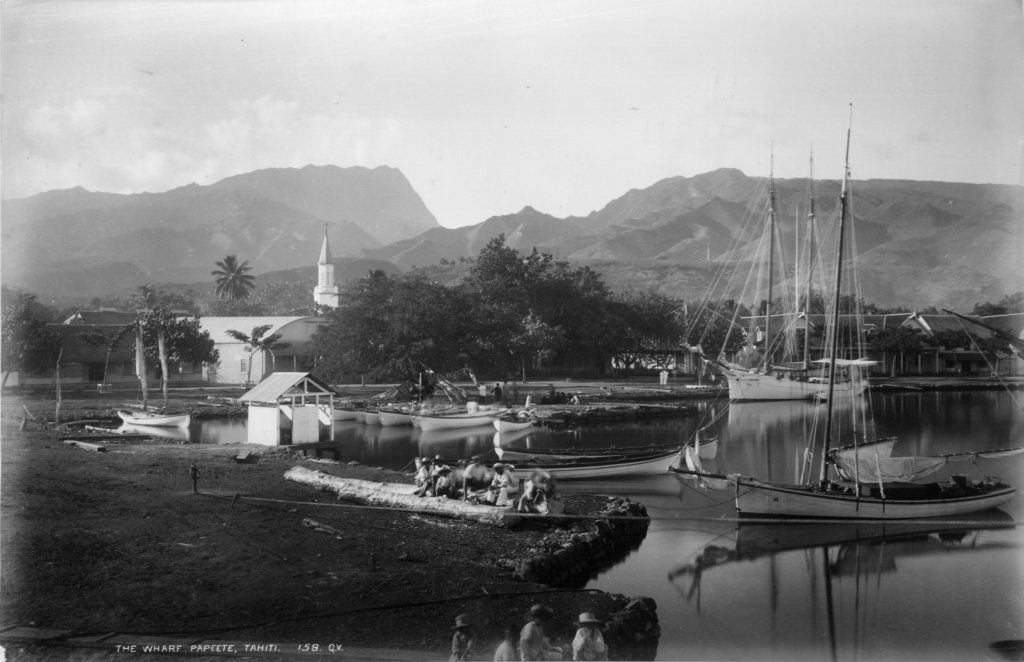

Gauguin arrived at Papeete Harbor in June 1891, long-haired and wearing a cowboy hat, expecting to brave a strange new land. But Tahiti was no longer an untamed paradise. Shocked, he moved to the remote district of Mataiea, on the island’s far west side. He embraced the land with all his senses, calling it “Noa Noa,” meaning “fragrant” or “perfumed.”

His arrival in Tahiti occured fifty years after the Franco-Tahitian war and a decade after its French annexation. For three years, from 1844 to 1847, the Tahitians, lacking the military power of the French marines, waged guerilla warfare on the island’s mountainous terrain. The French forcibly imposed a protectorate over the Kingdom of Tahiti and then annexed Tahiti in the 1880s.

Gauguin’s scant ethnographic knowledge, combined with his disillusionment when, on reaching Papeete, he first encountered the worst aspects of French colonialism, caused him to idealize the reality of Tahitian life before him. He immersed himself in Oceanic culture, avoiding the French schooners in the harbour and the Catholic missionaries. He began developing his so-called savage imagery, a hybrid of many sources, including ideas of the exotic encountered in art, literature and through access to primitive artifacts in Paris, well before his travels.

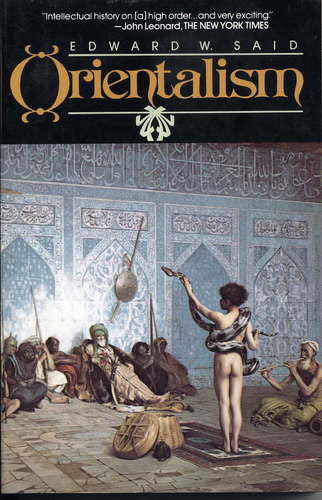

Gauguin was familiar with the Orientalist genre popular among academicians at the Paris salon. Nineteenth-century Orientalists such as Jean-Léon Gérôme had traveled to the East after the Napoleonic invasion (then defined as the regions of Turkey, the Levant, the Arabian Peninsula, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco) and returned with romanticized interpretations of foreign lands and their inhabitants. Their visualized colonial ideology was a form of cultural distortion that presumed the Islamic Orient’s inferiority and, intentionally or not, served to justify and perpetuate ideas of European dominance.

Orientalists focused on images laden with cultural significance and transformed them into metaphors and myths that served to contrast the civilized world of the West with the ‘barbarism’ of the Orient.

In 1978, Palestinian-American Edward Saïd published Orientalism, a study of European perspectives of the Orient, which laid the foundations of what we now understand as postcolonial studies and the beginnings of a discourse of the Other. Orientalism was essentially the false creation of the Orient as Other, which “was made the subject of lyrics, fantasies, and even novels, but it was never actual.” A prejudiced portrayal of non-western culture, Orientalism was repeatedly reproduced in scholarly works, travelogues, novels and poems that underscored a binary worldview where Europe (the West, the ‘self ’) comprised the rational, developed, humane, superior, virtuous, normal and masculine. In contrast, the Orient (the East, the Other, a surrogate version of the West or the ‘self ’) must be irrational, backward, despotic, inferior, depraved, aberrant and female.

Notably, such ideology had parallels in the academic nineteenth-century approaches to depicting the female, which insinuated concepts of the exotic, the passive, and the lesser. Foreigners and females were to be gazed upon, objectivized, and controlled by white western men. The enticing harem scenes were a perfect example of the twinning of dualistic ideas.

For western males, the harem was exotic and escapist, a respite from the strictures and taboos of Victorian society. When John Frederick Lewis went to Cairo, for example, he immediately “turned Turk,” painting idealized harem scenes where sensuous women happily cater to the men.

The Orient in these pictorial representations may have kindled Gauguin’s interest in the exotic, although he would soon grow critical of them.

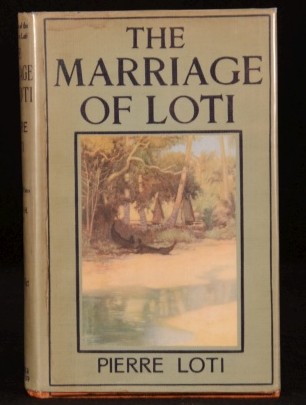

Among the literary sources which inspired ideas of the exotic in Gauguin was The Marriage of Loti by Jules Viaud, published in 1880. Viaud’s contemplations on love and life in the Orient used words such as strange, exotic, bizarre, mysterious, savage, weird, and incredible. Further, his paradisiacal descriptions of the tropical landscape insinuated a realm of sensual liberty and earthly delights that was stereotypical at best.

Le Mariage de Loti (The Marriage of Loti, Rarahu, or Tahiti) is an autobiographical novel. In 1872, at twenty-two, Julien Viaud (later known as Pierre Loti) was a naval officer stationed briefly in Papeete. In Tahiti, he “went native,” adopting native customs and loving the Tahitian women. He was swept away. In his words, “the air was charged with heady and unfamiliar perfume; quite unconsciously I abandoned myself to this enervating existence, overborne by the Oceanic spell.” His detailed diary became the source of the novel, which intermixes Loti’s true-life experiences with fiction. Le Mariage de Loti typically reflected contemporaneous imperialistic attitudes describing the native inhabitants as romantically exotic, child-like and innocent.

Taking the form of a journal, Le Mariage de Loti centres on the ill-fated romantic liaison between a British midshipman, Harry Grant, rebaptized Loti, and a fourteen-year-old Tahitian named Rarahu. The plot is rudimentary, episodic and circular. Loti falls in love with Rarahu but must leave her. After a brief adventure in the Marquesas, he returns to Tahiti and Rarahu, and to the realization of the impossible racial divide. Abandoning her for a second time to pursue love and excitement, he travels to Honolulu, Vancouver and San Francisco’s Chinatown. They reunite once more, but despite her conversion to Protestantism, his belief that she is irredeemably savage and doomed like the rest of her race to extinction ends the relationship. Loti finally leaves her, seeing her only once more, in his dreams, before learning of her horrible death.

Gustave Le Bon Les Lois psychologiques de l’évolution des peuples, first published, 1894 (English translation : The Psychology of Peoples)

Beyond the storyline, which establishes the freedom of Loti, and the passiveness of Rarahu, the language employed in Le Mariage de Loti echoes prevalent racist and eroticist writings of authors such as Gustave Le Bon. Le Bon popularized notions of moral and physiological decadence amongst primitive races. “Indo-Europeans,” he claimed, were uniquely capable of civilization, progress, and conquest, while others including the Australian Aborigines, Pacific kanakas, and African black were not. Instead, the latter experienced arrested development, unhealthy inbreeding or infantilism, and when in contact with a “superior people,” he wrote, “the primitive races are inevitably condemned to disappear at an early date.”

This view of Tahitians follows Herbert Spencer’s concept of so-called primitive societies as discussed in his publication Descriptive Sociology.

Spencer was well known for his thesis on social Darwinism. He was the originator of the expression “survival of the fittest,” which he coined after reading Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and which links social superiority with biology. Spencer asserted that Tahitians had a volatile disposition and depraved habits. They were cheerful, good-natured, and fond of jesting, but their emotions were violent and merciless.

Spencer’s Descriptive Sociology blatantly rejected early texts on primitivism, which first appeared during the 18th-century Enlightenment. In his Discourse on the Origins and Foundation of Inequality Among Men (1755), the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau researched ancient and contemporary peoples and compared their systems of laws and ideas of morality with modern Europeans. For him, the study of “original man,” “natural man,” “savage man,” and “man in his primitive state” was a means to understand the depth and breadth of human virtue and to measure the impact of civilization. His sober conclusion was that civil society and the value it placed on private property and its protection was the basis of all inequality.

The “noble savage,” a term Rousseau did not directly employ, spoke to the idealized indigene, the Other, uncorrupted by civilization, epitomizing humanity’s innate morality.

The Supplément au voyage de Bougainville, ou dialogue entre A et B sur l’inconvénient d’attacher des idées morales à certaines actions physiques qui n’en comportent pas, Denis Diderot’s series of philosophical dialogues, written in 1772 for the journal Correspondance littéraire, but not published until 1796, similarly, praised the primitive and criticized the civilized.

Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville, was a French admiral and explorer. He was acclaimed for his expeditions, including a circumnavigation of the globe in a scientific expedition in 1763, which included Tahiti. Diderot’s Supplément au voyage de Bougainville was a response to the views of Bougainville, who claimed the superiority of “savage” over “civilized” society.

The text is considered an example of the exotic glorification of foreign primitive people in contrast to the depravity of Western civilization. Diderot discusses the sexual freedom of Tahitians vis a vis the European double standard. He proposed that envy, jealousy, coquetry and infidelity were foreign to Tahitian men. “We possess already all that is good or necessary for our existence,” says Diderot’s wise Tahitian, “Do we merit your scorn because we have not been able to create superfluous wants for ourselves?” While it may seem that Diderot was advocating for a return to nature, his purpose was to provide the meritorious aspects of primitive societies.

Imaginings of the exotic were also kindled by the newly opened Musée d’Ethnographie in Paris. The Trocadéro Museum opened to the public in 1878 with artifacts from across the globe, including West Africa and Oceania. Carved clubs, bowls, masks, and sculptures were inspirational to Gauguin and other artists interested in exploring new perspectives in art.

Gauguin’s exposure to the exotic and the primitive therefore predated his departure for Tahiti and was influenced by a variety of disparate sources as manifested in his painted relief sculpture Woman with Mango Fruits of 1889.

7.7

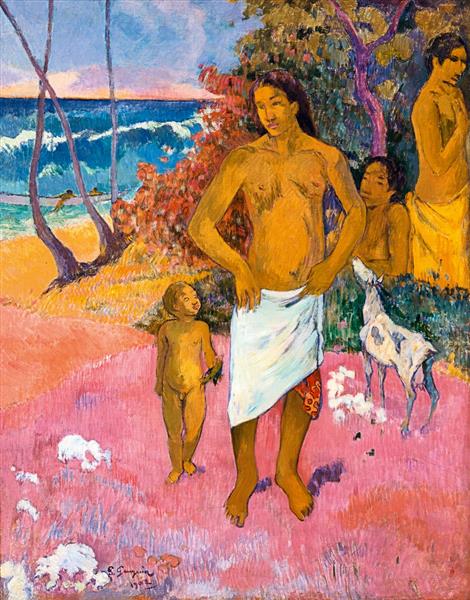

| Fantastical Figures and Scandalous Subjects

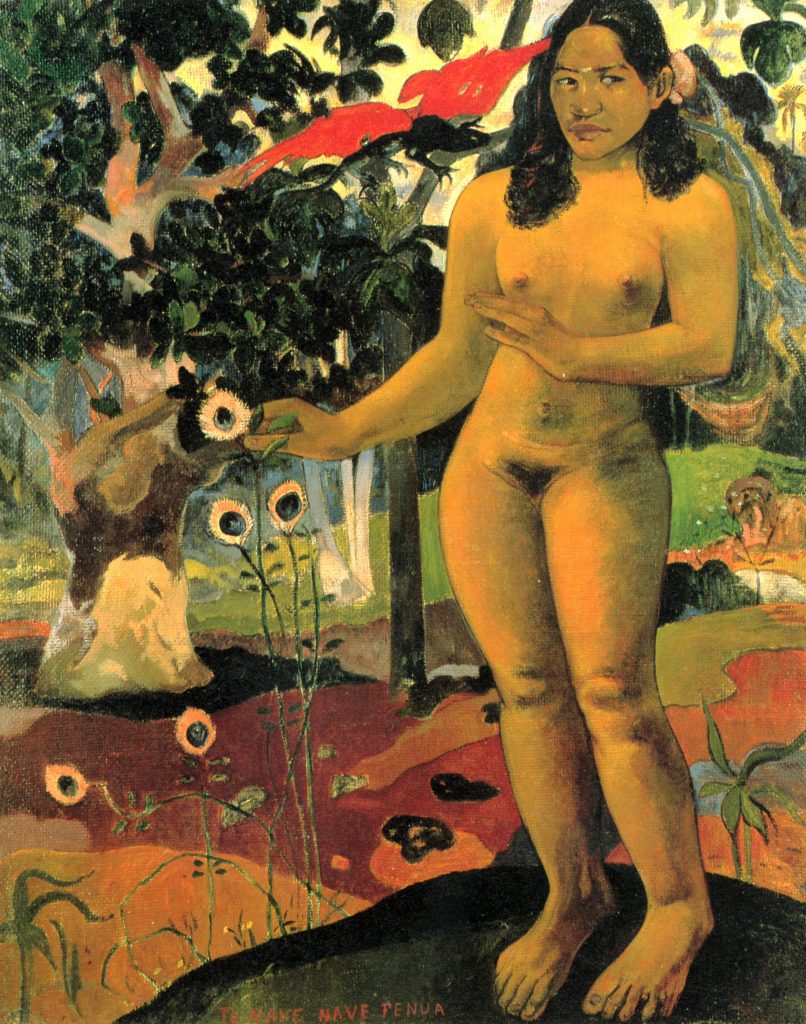

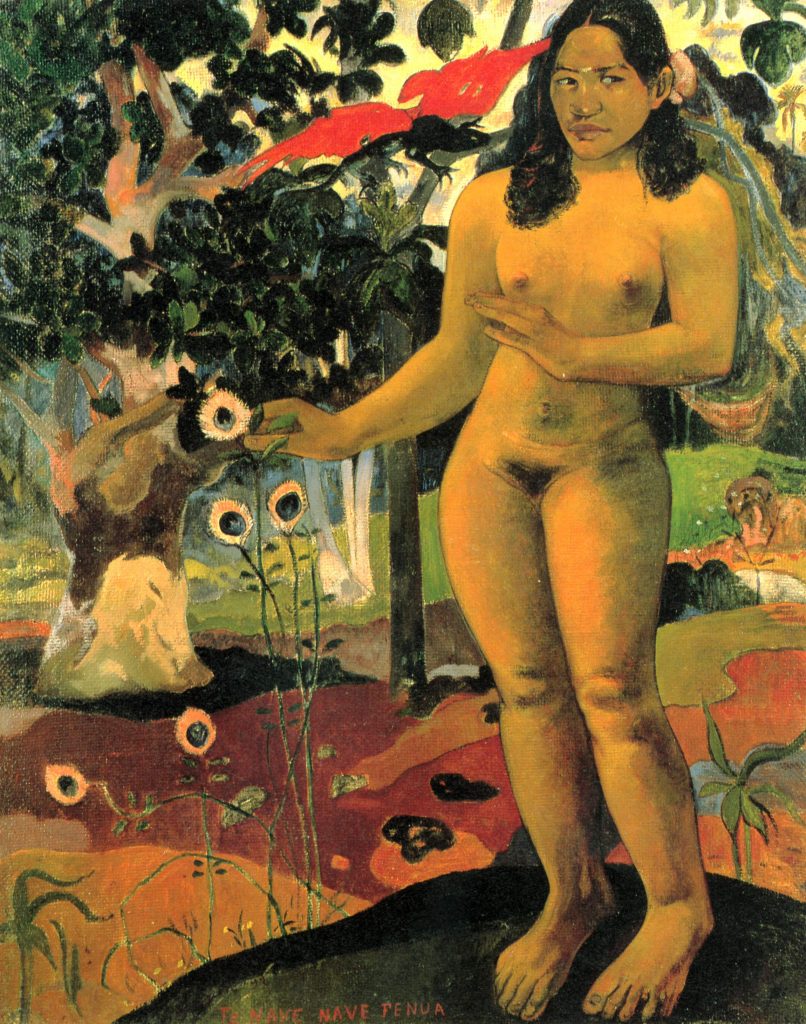

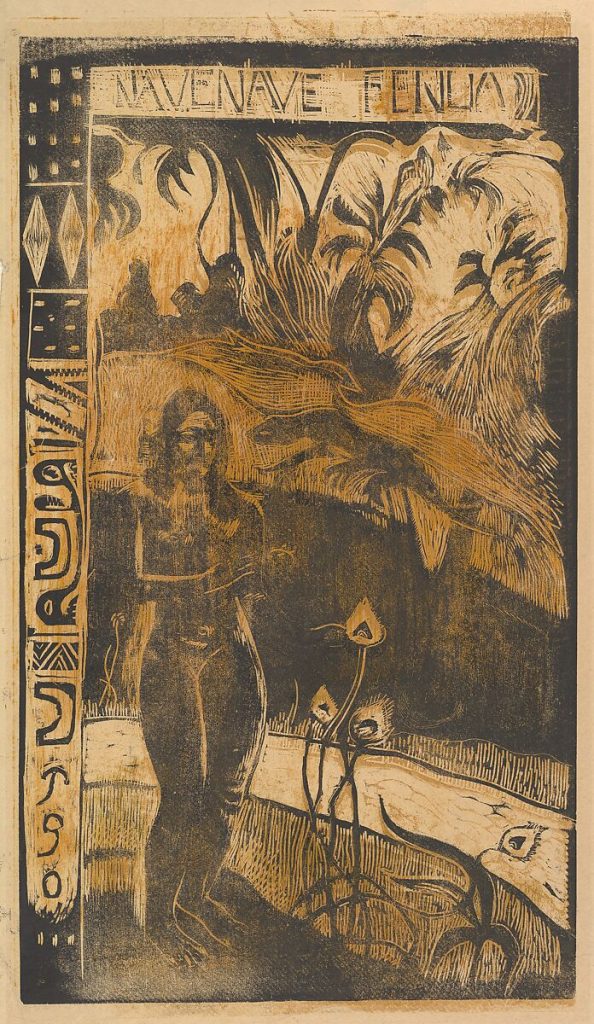

The Delightful Land is one of Gauguin’s most complex early Tahitian paintings. When he wrote about it in his Intimate Journals he quoted the art critic Achille Delaroche: “Fantastical orchard. Its seducing plants stimulate the sexual desire of Eve in the Garden of Eden. Her arm timidly extends, trying to pick an evil flower. The monster Chimera flutters its red wing to graze her temple.”

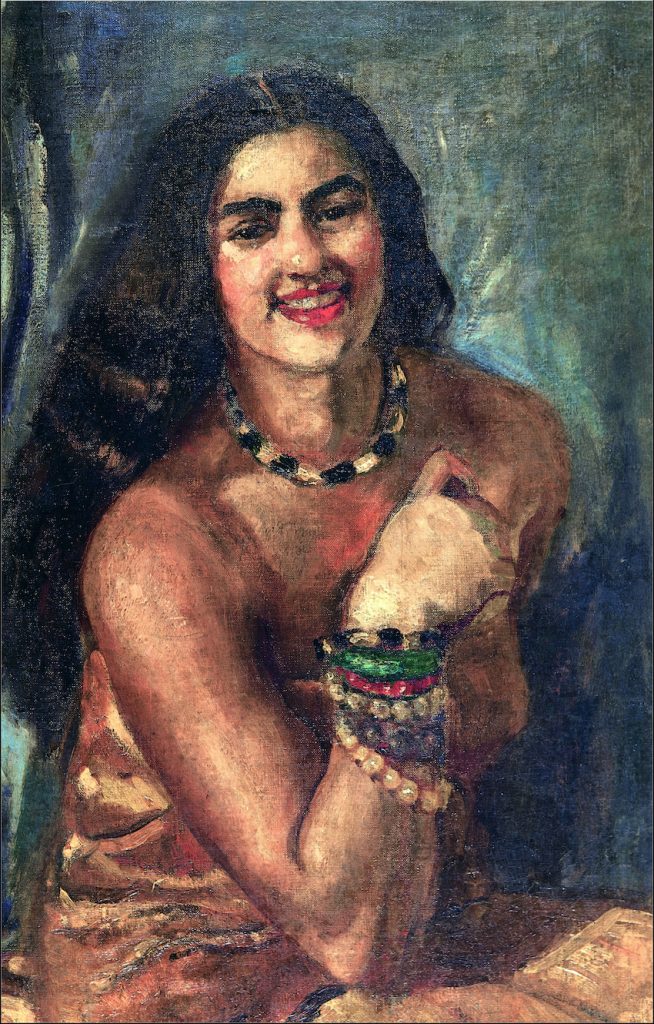

The Tahitian Eve pictured here is naive in her nudity. She is placed in an idyllic nature, harmonious and joyful but for the small demon that appears nearby. Strange peacock-like flowers and anthropomorphic plant life stand in for the original serpent and the apple of original sin. The girl’s naked body appears to sway in time to the rhythms of the unheard upa upa.For Gauguin, she was like Loti’s Rarahu, always “singing and loving.”The model was Teha’amana, Gauguin’s thirteen-year-old ‘native wife.’ French colonialists like Gauguin commonly took native wives, but such unions were not legally binding.

In The Delightful Land, Teha’amana is not shown as conventionally beautiful. She is depicted as heavy-set and compact, with broad shoulders, wide thighs, thick calves, and large hands and feet. She is dark-skinned and black-haired and is disfigured by a polydactyl foot, a feature which prompted a contemptible comparison to a simian with feet adapted for use as hands. Another critic judged her to be ‘lower’ on the scale of evolution.

In addition, her posture and anatomy emphasize boyishness, insinuating a different assault on the depictions of the female nude. Gauguin wrote in Noa Noa: “there is something virile in the (Tahitian) women and (something) feminine in the men.” And when his friend and literary collaborator Charles Morice described Teha’amana, he called her an “androgynous little girl.”

Teha’amana/Eve is the embodiment of European racist tropes. Her image contrasts, even clashes, with well-known conceptions of the Venus of western mythology. She represents but does not resolve the contradictions. This is echoed by Gauguin’s own words:

She was to all intent my little wife; I loved her truly. And yet there was a great gulf between us-a great gate forever shut. She was a little savage; between us two who were one flesh there was a radical difference of race and utter divergence of views on the first elements of things. If my ideas and conception were often impenetrably dark to her, so were hers to me…I remember what she had once said to me: “I am afraid lest the same god did not create us both. In truth we were the offspring of two types of nature absolutely apart and dissimilar and the union of our souls could only be brief, imperfect and stormy.”

Gauguin’s grasp of evolutionary ideas is crudely expressed in these thoughts: “The feet of a quadrumane! So be it! Like Eve the body is still an animal thing. But the head has progressed with evolution, the thinking has acquired subtlety, love has imprinted an ironic smile on the lips and naively she searches in her memory for the why of times past and present.”

Is she then a transformative figure synthesizing both European and non-Western mythology? In Polynesia, bruised heads and feet, the transformation of men and women into rooted trees and plants, and the dismemberment and dispersal of bodies were associated with Tahitian genesis mythology. Thus, she is an Eve born of the earth and a modern Tahitian born of a particular historical union. She is not merely a primitive product of nature but a complex creature of culture, her binarism highlighted by her foot with six toes.

Loti’s stereotypical Rarahu had become a foil by the time Gauguin departed from Tahiti in 1893, and the book was a representation of the bourgeois ideas of Polynesia that Gauguin had sought to overcome. Whereas Viaud described Rarahu as “a little creature,” Teha’amana is a veritable giantess, a fact clearly articulated by Gauguin, “This is not some little Rarahu, listening to a pretty ballad by Pierre Loti…She is Eve after the Fall, still able to go about unclothed without being immodest, still with as much animal beauty as on the first day.”

Strength, sexuality, confidence, not weakness, innocence and passivity were the traits Gauguin wished to depict in the representation of this and other Tahitian women. Whereas Rarahu’s “business in life,“ as written by Viaud, was “simple and mindless … to dream, to bathe- especially to bathe-to sing and to wander through the woods,” Tahitian Eve was far more complex.

Gauguin noted how the Tahitian body, naked, agile, powerful, and erotic was specifically adapted for a Pacific Island life and culture, which (he) supposed was ancient and slow to change.

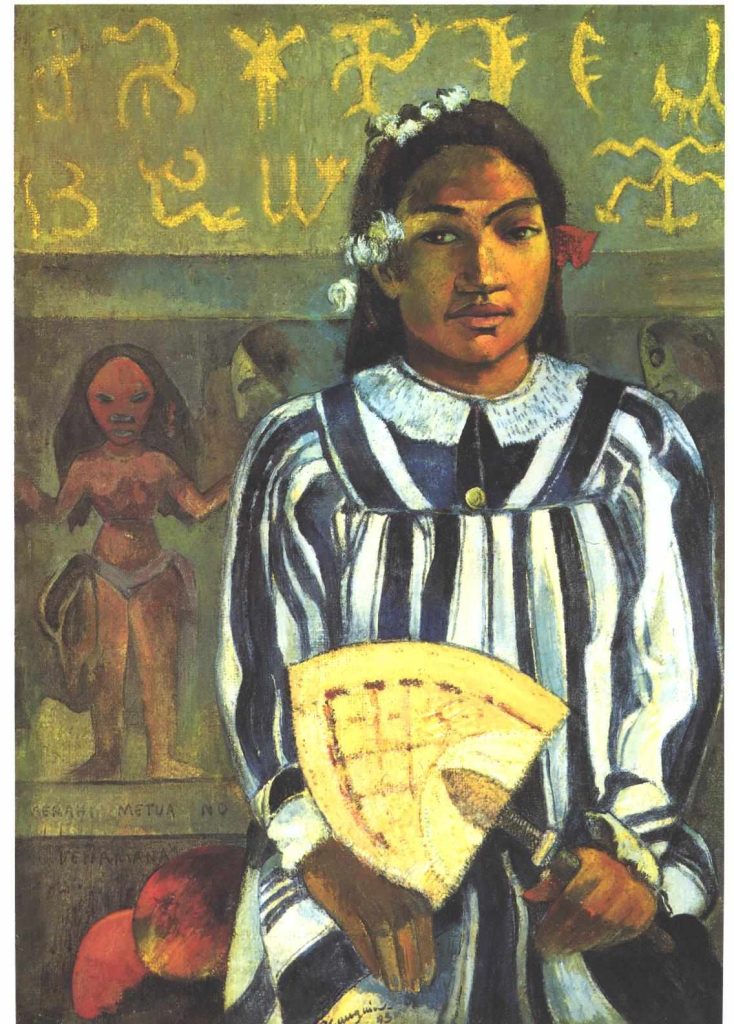

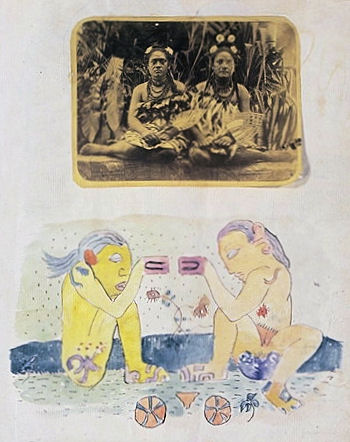

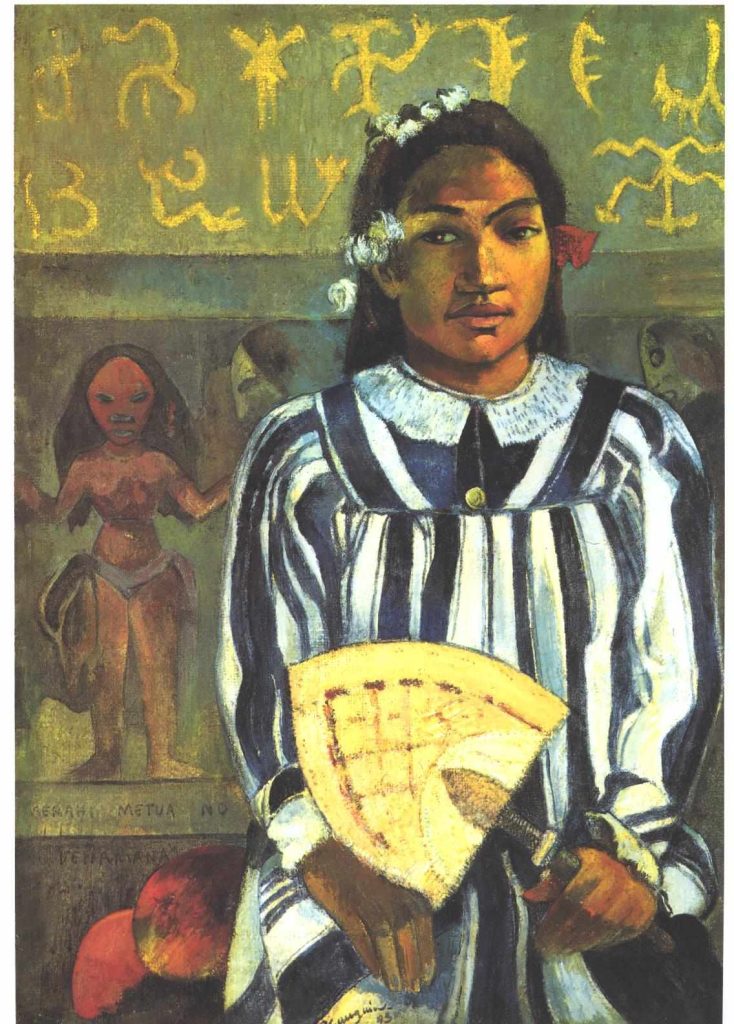

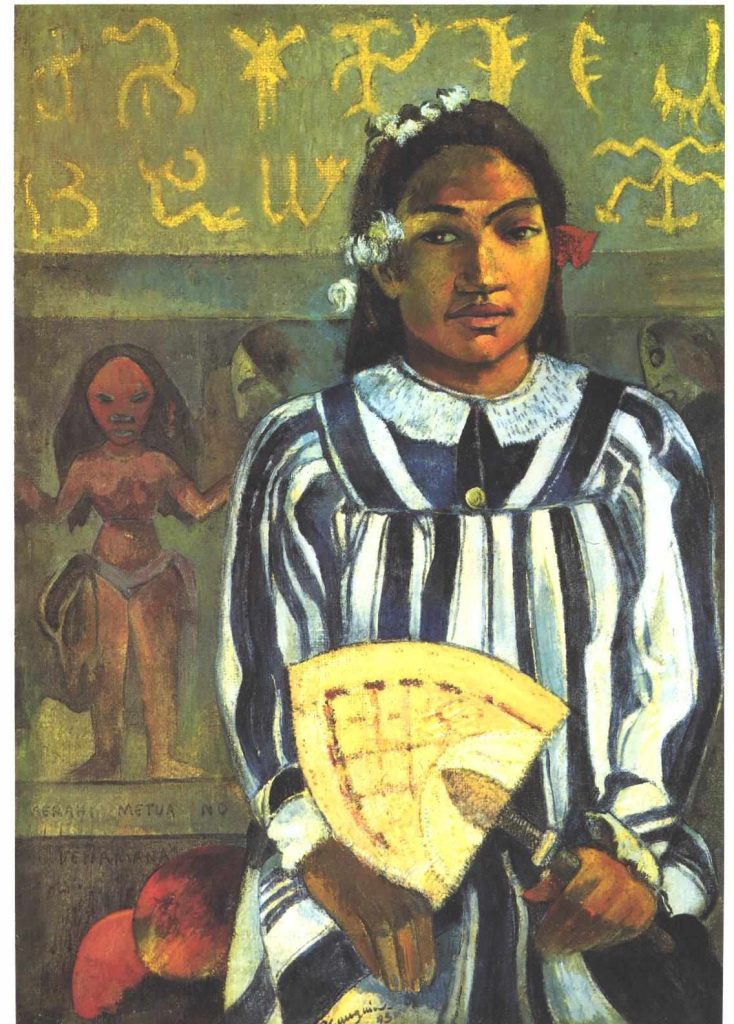

Painted near the end of Gauguin’s first Tahitian trip, Tehamana Has Many Parents, or The Ancestors of Tehamana, depicts his teenage lover again. The title references the rich ancestral past of Tahiti, where adoption and foster parentage were common. Here Teha’amana is surrounded by ancient and new symbols: the island’s ripe mangoes, an inscription plucked from a tablet on Easter Island, and a background frieze depicting dancers whose forms echo the glyphs above. The open-armed female figure to the right of Teha’amana is in native costume while she is clothed in western dress, perhaps a comment on the modernizing of the island.

The complexities of colonial influence, evidenced by the fashionably hybrid attire, may also be seen in this photographic group portrait of women in missionary dress.

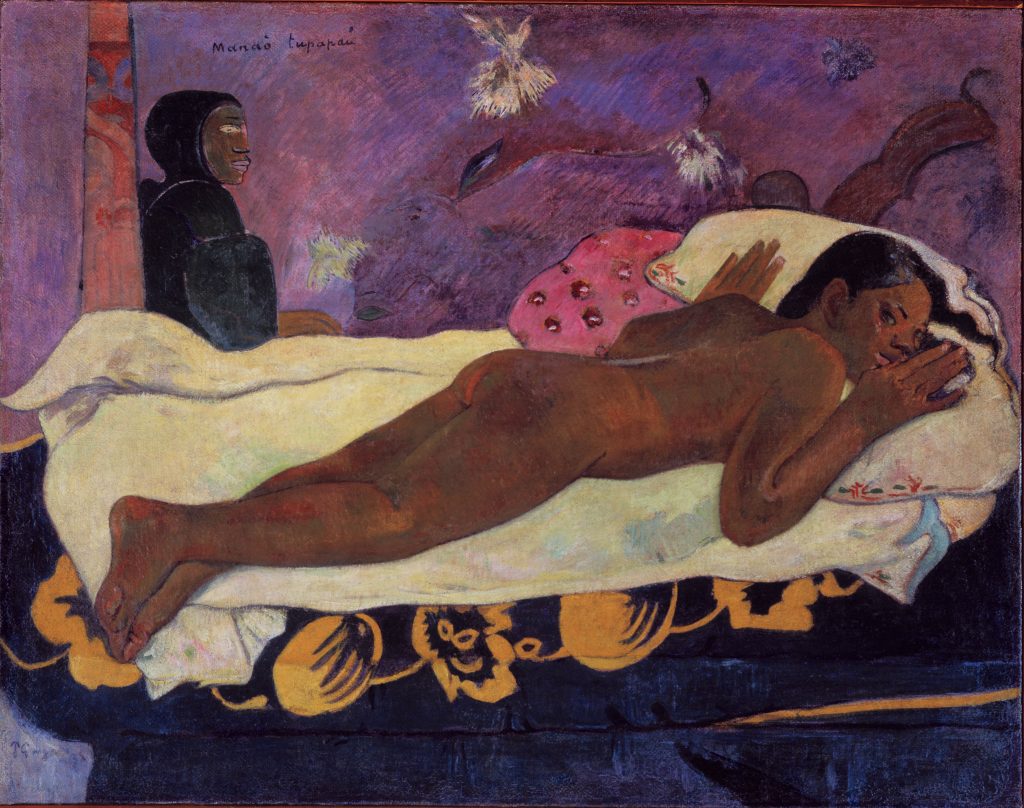

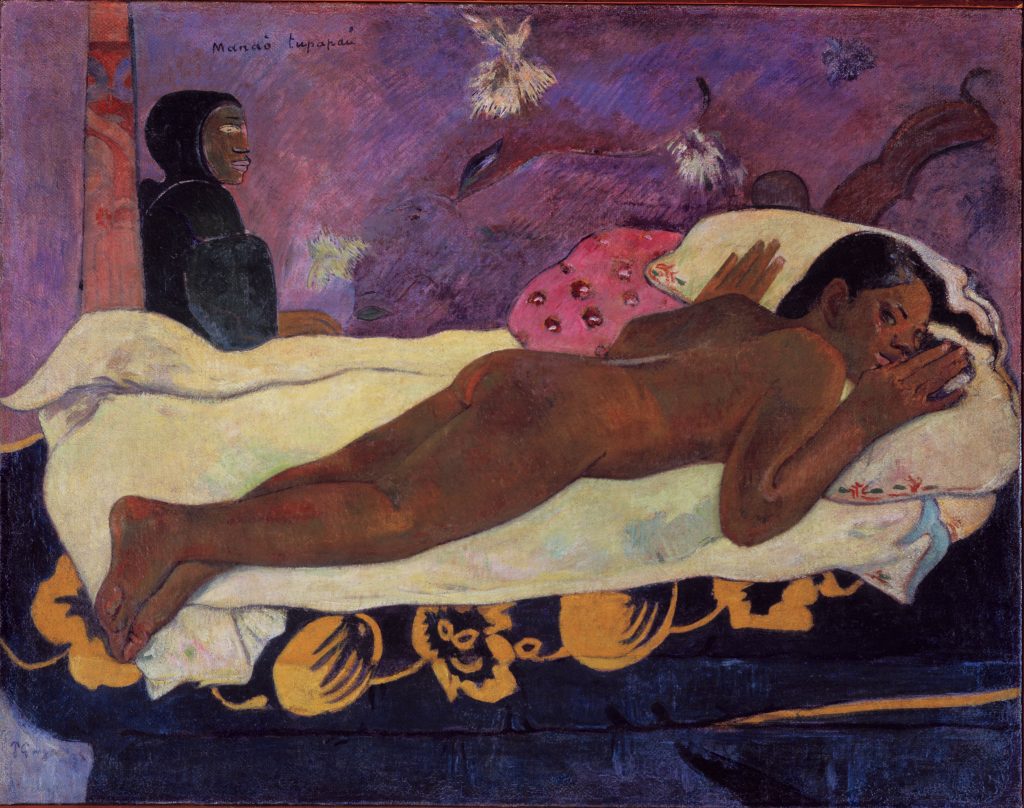

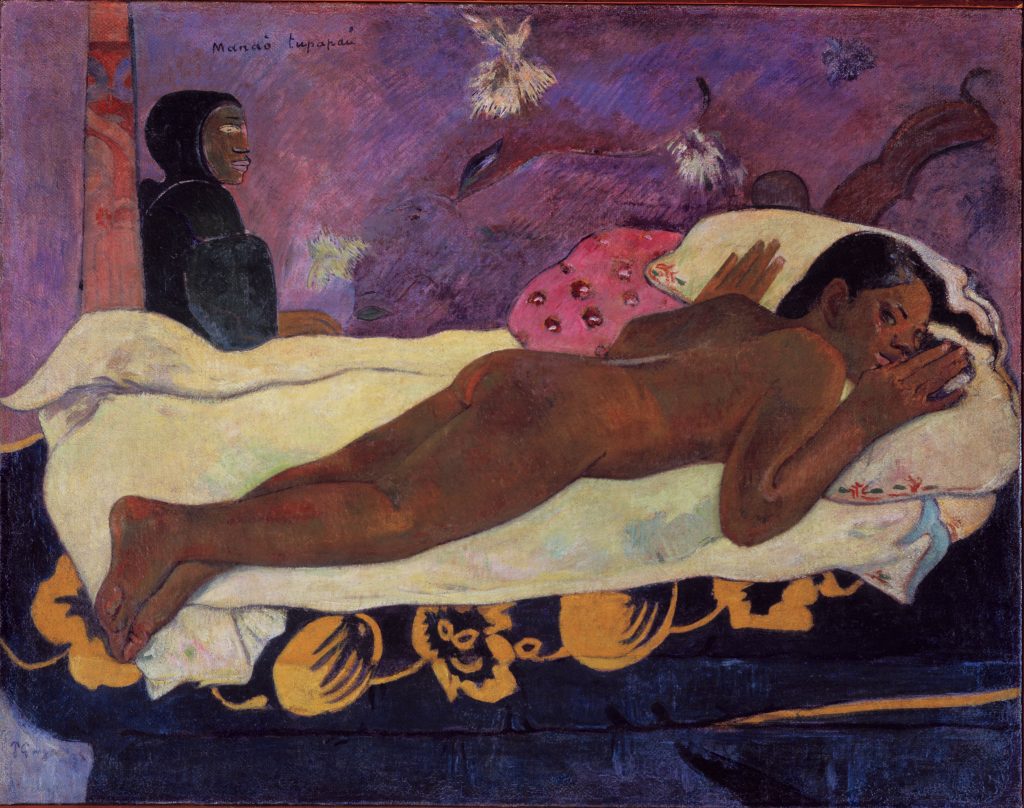

Teha’amana was the model for a third painting by Gauguin entitled Spirit of the Dead Watching. This time the imagery is overtly sexualized. Yet, while the pose is highly suggestive, the face shows apprehension. The image was deemed scandalous from the time of its exhibition in Paris in 1894 and continues to elicit criticism amongst contemporary art historians today. At the time of the painting’s exhibition, Gauguin wrote to his wife Mette in Paris to prepare her for the controversy ahead, arming her with a different narrative, that of a woman transfixed by the fear of a Maohi (phantom).

I have painted a young girl in the nude. In this position a trifle more, and she becomes indecent. However I want it this way as the lines and movement interest me. So I make her look a little frightened. This fright must be excused if not explained in the character of a person, a Maohi. These people have by tradition a great fear of the dead. One of our young girls would be startled if surprised in such a posture. Not so a woman here … Here endeth the little sermon, which will arm you against the critics when they bombard you with their malicious questions.

The young girl’s fearful expression is directed at the viewer, gazing upon her recumbent nude body. It highlights that Gauguin’s alternative narrative was spurious, reducing ancestor worship’s complexities to mere superstition.

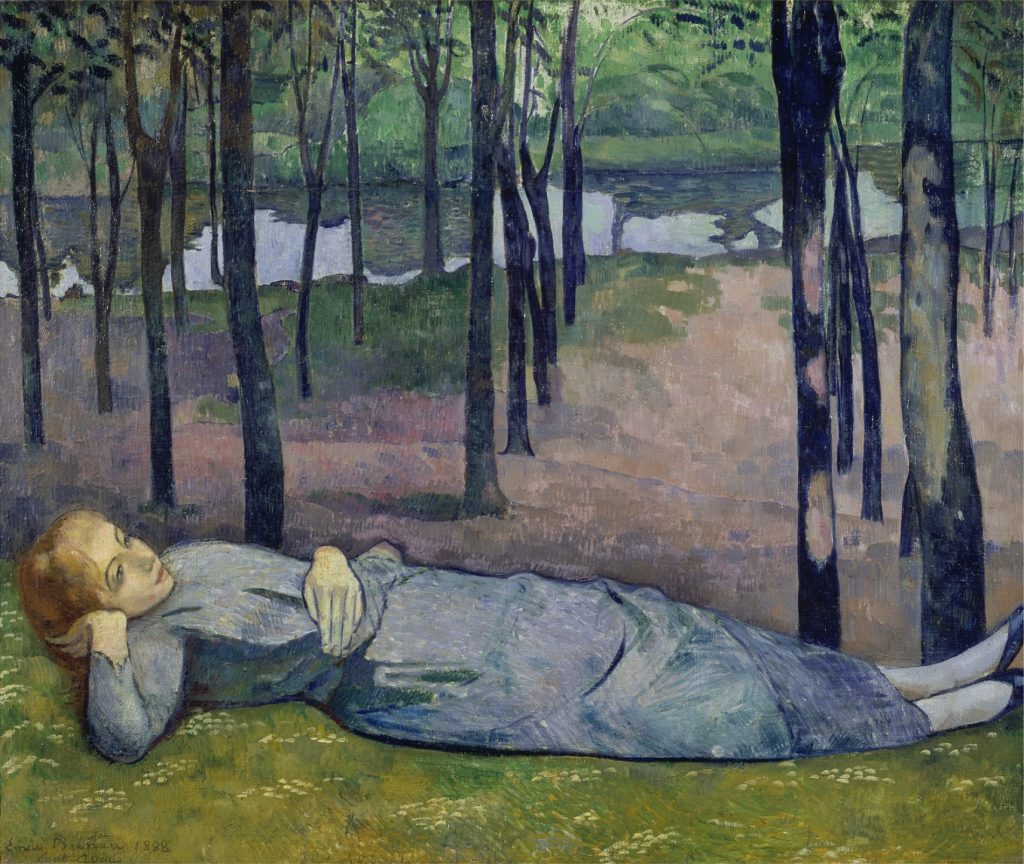

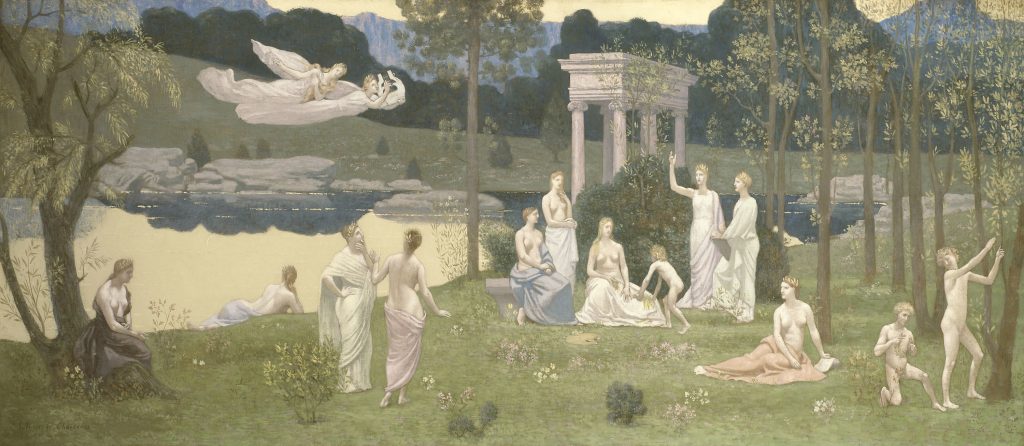

Despite its allusions to primitivism, the suggestive nature of the image was familiar, not uncommon, transcending cultural contexts. Gauguin had exoticized the erotic. Among the French precedents that exist are Puvis de Chauvannes’s The Dream (1883), Bernard’s Madeleine au Bois d’Amour (1888), Gauguin’s The Loss of Virginity (1890-91) and, of course, Manet’s Olympia.

Compositionally, the similarities between Olympia and Mano Tupapau are striking. The massive bed across the plane of the painting, a naked body served up on a sheet of dazzling white linen and set off by a patterned background, the expressive hand gestures. Both compositions contrast a recumbent nude and a clothed upright figure. One significant difference is that in Gauguin’s painting, the maid figure is now the spirit of death.

The story behind Mano Tupapau is repeated in Gauguin’s Noa Noa manuscript:

One day I had gone to Papeete. I had promised to come back that same evening. On the way back, the carriage broke down halfway: I had to do the rest on foot. It was one in the morning when I got home. Having at the moment very little oil in the house – my stock was due to be replenished – the lamp had gone out, and the room was darkness when I went in…. Tehura (Teha’amana) lay motionless, naked, belly down on the bed: she stared up at me, her eyes wide with fear and she seemed not to know who I was. For a moment I felt a strange uncertainty. Tehura’s dread was contagious; it seemed to me that a phosphorescent light poured from her staring eyes. I had never seen her so lovely; above all, I had never seen her beauty so moving… Perhaps she took me, with my anguished face, for one of those legendary demons or spectres, the tupapaus that filled the sleepless nights of her people.

Gauguin insisted that the work was merely a representation of Tahitian superstition. Without its superstitious aspect, it was simply a nude. He continued:

According to Tahitian beliefs, the title has a double meaning… either she thinks of the ghost or the ghost thinks of her. To recapitulate: musical part-undulating horizontal lines-harmonies in orange and blue linked by yellows and violets from which they derive. The light and greenish sparks. Literary part-the spirit of a living girl linked with the spirit of death. Night and day. This aforementioned genesis is written for those who always have to know the whys and whereafter. Otherwise, the picture is simply a study of a Polynesian nude.

Gauguin also rationalized his choice of risky imagery, penning the following:

A young native woman lies flat on her face. Her terror-stricken features are only partially visible … I am attracted by a form and movement and paint them with no other intention (than a nude) … In this particular state, the study is a little indecent. But I want to do a chaste picture and above all render the native mentality and traditional character … What can a nude Kanaka girl be doing quite naked on her bed in a rather risky pose as this? She can be preparing herself of course for lovemaking. This is an interpretation which answers well to her character but is an indecent idea which I dislike. If on the other hand she is asleep the inference is that she has had intercourse which also suggests something indecent. The only conceivable mood is one of fear. But what sort of fear possessed her? Certainly not the fear shown by Susannah when she was surprised by some old men. There is no such fear in the South Seas. No, it is of course the tupapau. The Kanakas are always afraid and leave a lamp light at night… As soon as this idea of a tupapau occurred to me I concentrate on it and make it the theme of my picture, the nude thus becomes subordinate.

That the subject of this painting was Gauguin’s thirteen-year-old “wife,” extends its controversial aspects. These relationships between European men and Tahitian women, formalized on the Island and meaningless elsewhere, were predicated upon the wielding of the power of men, regardless of culture. The racist structures which empowered western men to destroy the kinship system of other cultures may be seen as a racialized extension of the phenomenon. Western narratives such as Marriage de Loti reflect this. While Teha’amana’s self-perception was that of a young wife, from a European perspective, she was inconsequential, a prostitute.

The image and the artist’s written account speak of colonialism, racism, and misogyny. The young woman is “terrified out of her mind” by a spectre suggests that she is ruled by emotion and mysticism, incapable of rational thought.

7.8

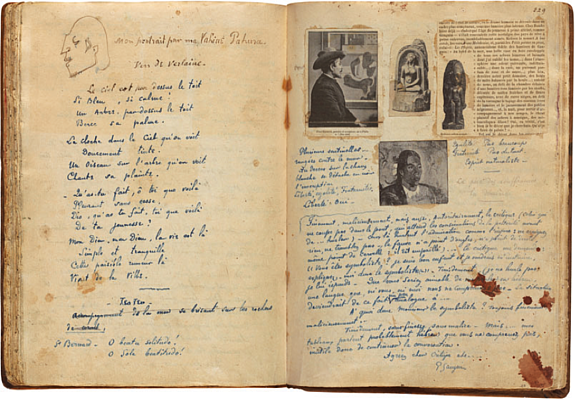

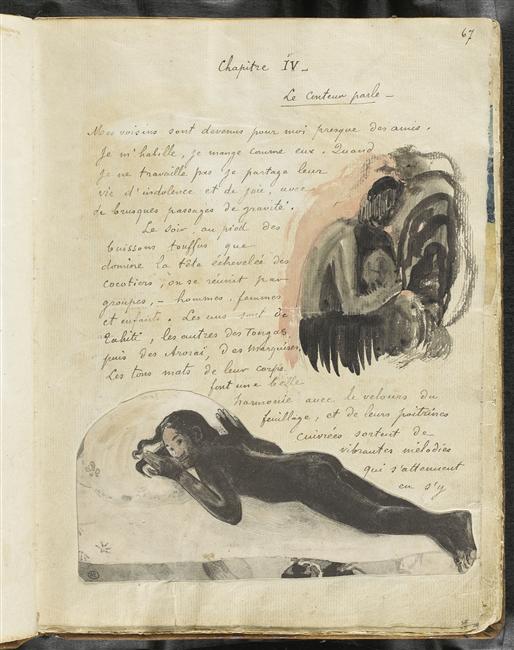

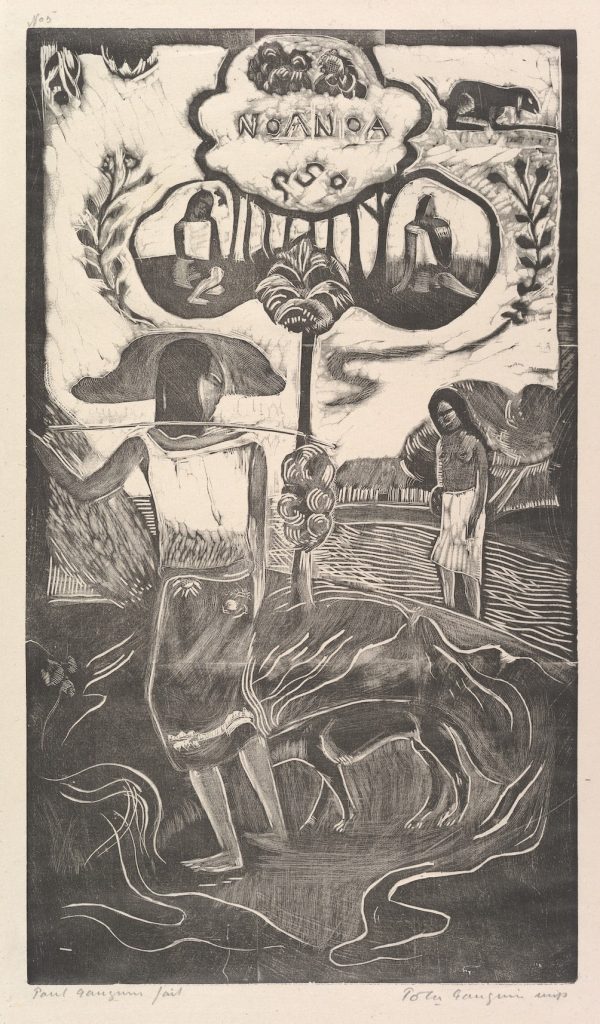

| Noa Noa

In her book review of “Savage Tales: The Writings of Paul Gauguin by Linda Goddard” (Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 2 (Autumn 2020), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2020.19.2.9), Mary Morton outlines the author’s focus on Gauguin’s literary career as a whole:

Paul Gauguin and the extraordinary range of his creative output—paintings and drawings, wood and ceramic sculpture, prints, and prose—pose one of the stickier challenges for historians of nineteenth-century art. … His visual art was intended to provoke and shock, and his prolific textual output was riddled with statements that were racist, sexist, anti-French, anti-colonial, and frequently untruthful and contradictory. He was a contrarian, an inveterate liar, and one of the most inventive and compelling artists of the later nineteenth-century.

… (Goddard) also critiques the dismissal of Gauguin’s writings as amateurish and narrowly self-serving, and secondary to his larger artistic project. This reputation was reinforced by Gauguin himself … aligning a fragmentary, non-linear, and apparently simple style with his “savage” identity. Goddard makes the point that his primitivist self-fashioning against academic conventions extended to his literary work.

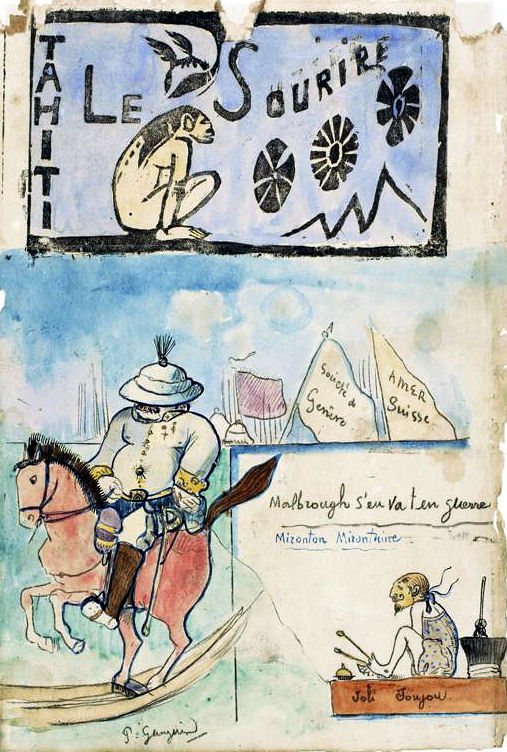

From Ancien Culte Mahorie, Cahier pour Aline, and Noa, all of 1893, to the satirical broadsheet he produced in his final years in the Marquesas titled Le Sourire, Goddard’s study peels back this maneuvering to define a distinct authorial practice worthy of serious literary attention.

When Gauguin returned to Paris in 1893, he began writing his semi-fictionalized Noa Noa, maybe to accompany the Durand-Ruel exhibition of his Tahitian paintings in Paris that same year. While he wrote the preliminary draft himself, he invited collaborators, such as the poet Charles Morice, to elaborate and edit. Back in Tahiti, he continued to add material, including a section titled Diverses Choses. Alastair Wright explains in Paradise Lost (Artforum 49, no. 1 (September 2010):

Diverses Choses (Various Things, 1896–98), a sprawling manuscript the artist penned in Tahiti, opens with a description of its own form: “Scattered notes, without order like Dreams, made up of fragments, like life. And because of the fact that several collaborate here; the love of beautiful things glimpsed in one’s neighbor’s house.” The first sentence aptly characterizes Gauguin’s aphoristic and disjointedly anecdotal writing; the second makes explicit that the pages to follow will be constructed not only from the artist’s own thoughts but also from the words of others, textual fragments that caught the artist’s eye and that he harvested from a dizzyingly wide array of sources. That this is stated openly requires us to think differently about Gauguin: not as a plagiarist, but as someone who allows us to sense that he worked always with the already written. His images may make the same point.

Noa Noa resembled an artist’s book, a livre d’artiste, more than a conventional book. It contained original drawings, watercolours and prints, Morice’s poems, and “more or less original texts in which Gauguin pens a fictional ‘memoir’ of his life in Tahiti.” Goddard goes on to identify “strains of imperialist ideology and romantic travel writing, as well as a darker shift in which the “familiar trope of a land of plenty, characterized by leisure and sexual liberty, whose beauty was embodied by the compliant and youthful Tahitian woman, became tainted by the fatalistic narrative of extinction.” Morton continues,

While Noa draws heavily on travel-writing tropes, its most compelling dynamic is in Gauguin’s complex self-presentation as both primitivized and irredeemably European … The description of his discomfort, alienation, and loneliness belies the fantasy of a seamless immersion in this exotic paradise. Goddard notes passages born of self-awareness and social insecurity in which he challenges the boundaries of colonial, sexual, and gender identity, such as his embarrassment at being stood up by the villagers for a communal event, or his recognition of Tehamana’s confident serenity relative to his own sense of fearful hesitancy (84–5). He does not, then, feed conventional notions of primitivism as having to do with some essential element of Polynesia, but rather acknowledges it as an ideological construction inextricably bound up with the conditions of colonialism and capitalist modernity.

Perhaps Goddard’s greatest contribution in Savage Tales is her restoration of the sense of material complexity to Noa Noa and Gauguin’s other ambitious manuscripts… The collage aesthetic and the brilliant symbiosis of word and image is conveyed through beautiful reproductions of carefully selected album pages. She argues for the aesthetic coherence linking the artist’s visual oeuvre to his literary work, involving the “bricolage” of motifs, and the process of appropriation, reiteration, fragmentation, and repetition.

Gauguin returned to Paris in September 1893 and exhibited his ‘savage’ Polynesian paintings, including Spirit of the Dead Watching (Manao Tupapau), which he considered the most significant among them. The works were not much-admired. Self-Portrait with Hat, within which Manao Tupapau is inserted as a mirror image, is a rebellious response to his lukewarm welcome home.

7.9

| Gauguin’s Existential Manifesto:

Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going?

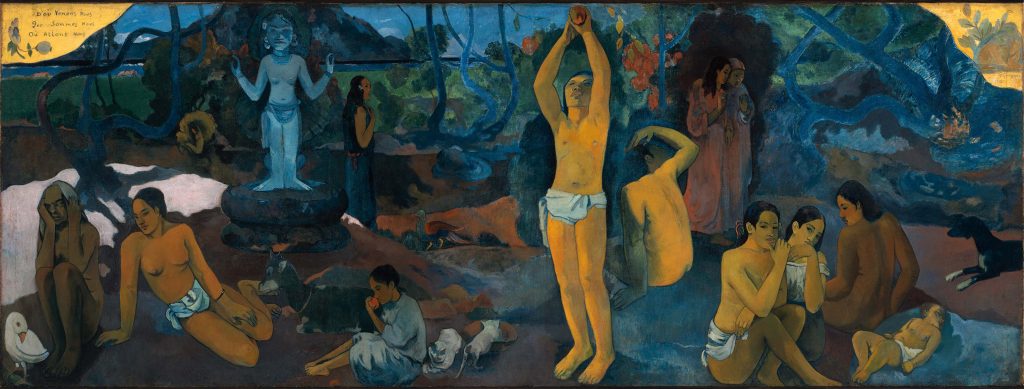

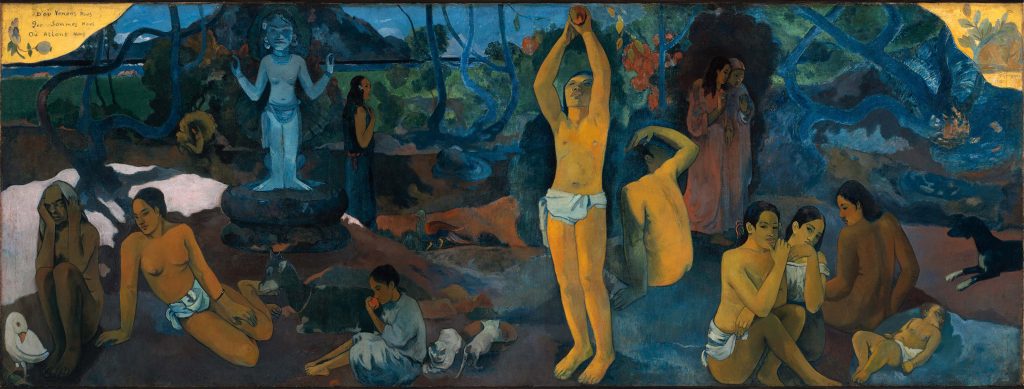

Gauguin returned to Polynesia in 1895. Two years later, he created a massive painting that stands as his chef-d’oeuvre. “I believe that this canvas not only surpasses all my preceding ones, but [also] that I shall never do anything better, or even like it,” he wrote to his dealer, Daniel de Monfried, in Paris.

The enormous painting is Gauguin’s existential manifesto, in his words, “a philosophical work on a theme comparable to that of the gospel.”

Writing about it in 1898, he begins with his attempted suicide, suggesting that the painting came from a confrontation with the abyss of death.

I went into the mountains, where my body would have been devoured by ants. I had no revolver, but I had arsenic … Whether the dose was too strong or whether vomiting counteracted the action of the poison I don’t know, but after a night of terrible suffering I returned home.

…

But before I died, I wished to paint a large canvas that I had in mind and worked day and night that whole month in an incredible fever.

The suggestion is that the painting was ignited by an imaginary confrontation with death’s abyss. In describing the work, he emphasizes its archaistic fresco-like quality and the magical landscape setting. He enumerates its diverse dramatis personae: children, gossips, “figures (genderless), old women, farm animals, totemic and allegorical creatures and an idol.” Gauguin continues:

It is a canvas four meters fifty in width, by one meter seventy in height. The two upper corners are chrome yellow, with an inscription on the left and my name on the right, like a fresco whose corners are spoiled with age and which is appliqued upon a golden wall. To the right at the lower end a sleeping child and three crouching women. Two figures dressed in purple confide their thoughts to one another. An enormous crouching figure, out of all proportion and intentionally so, raises its arms and stares in astonishment upon these two who dare to think their destiny. A figure in the center is picking fruit. Two carats near a child. A white goat. An idol, its arms mysteriously raise in a sort of rhythm, seems to indicate the beyond. Then lastly an old woman near in death appears to accept anything. To resign herself to her thoughts. She completes the story. At her feet a strange white bird, holding a lizard in its claws, represents the futility of words. It is all on the bank of a river in the woods. In the background the ocean, then the mountains of a neighbouring island. Despite changes of tone, the colouring of the landscape is constant, either blue or Veronese green. The naked figures stand out on it in bold orange. If anyone should tell Beaux-Arts pupils for the Rome competitions: “The picture you must paint is to represent Where do we come from? Where are we? Where are we going? what would they do? So I have finished a philosophical work on a theme comparable to that of the gospel.

In essence, Gauguin was mythologizing the life cycle. In a letter to the Symbolist poet Charles Morice in 1901 Gauguin scribbled out his ideas and imagery

Where Are We Going?

An old woman near death

A strange bird to conclude

Who Are We?

Daily existence.

The man of instincts asks himself what all this means.

The Source.

A Child.

The beginning of Life.

The bird concludes the poem [through] a comparison between the inferior being and the intelligent one in this large ensemble announced by the title. Behind a tree, two sinister figures, dressed in sadly colored clothes, converse near the tree of science, their dolorous aspect caused by this science itself, in comparison to [the feelings of] simple beings in a virgin nature that could be a human concept of paradise [if] they abandoned themselves to the happiness of living.

While the work demands to be read like a book, there is no underlying narrative to anchor it. Therein lies its obscurity, its ambiguity. There is neither conceptual clarity nor is there formal cohesion. The individuals and groupings are isolated from one another, and the landscape elements, trees, streams, caves, breaking waves, and distant mountains, appear stand-alone, sometimes in conflict.

The painting was shipped to Paris in July 1898 along with eight others, and in November, the Tahitian group of works was shown at the gallery of Ambroise Vollard. Where do we Come from? What are we? Where are we going? was the centrepiece of the exhibition.

Despite careful planning, advance promotion, and publicity, the show was a critical and financial failure. Gustave Geoffroy described it as a “too strongly held belief in artifice …but a very charming taste for nature.”

In 1901, explaining how his work differed from that of Puvis, Gauguin wrote, “Puvis explains his idea, yes, but he does not paint it. He is Greek, whereas I am a savage, a wolf in the woods without a collar. Puvis will call a picture Purity, and to explain it will paint a young virgin with a lily in her hand-a hackneyed symbol, but which is understood by all. Gauguin under the title Purity, will paint a landscape with limpid streams; no taint of civilized man, perhaps an individual.”

Gauguin’s criticism of Puvis was essentially his rejection of western art. Paradoxically, by dismissing the work, he denies Puvis’ allegorical approach, while his own large paintings invoke the extra pictorial albeit through a medley of appropriated and invented sources.

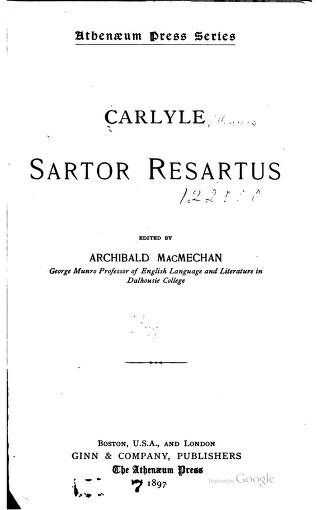

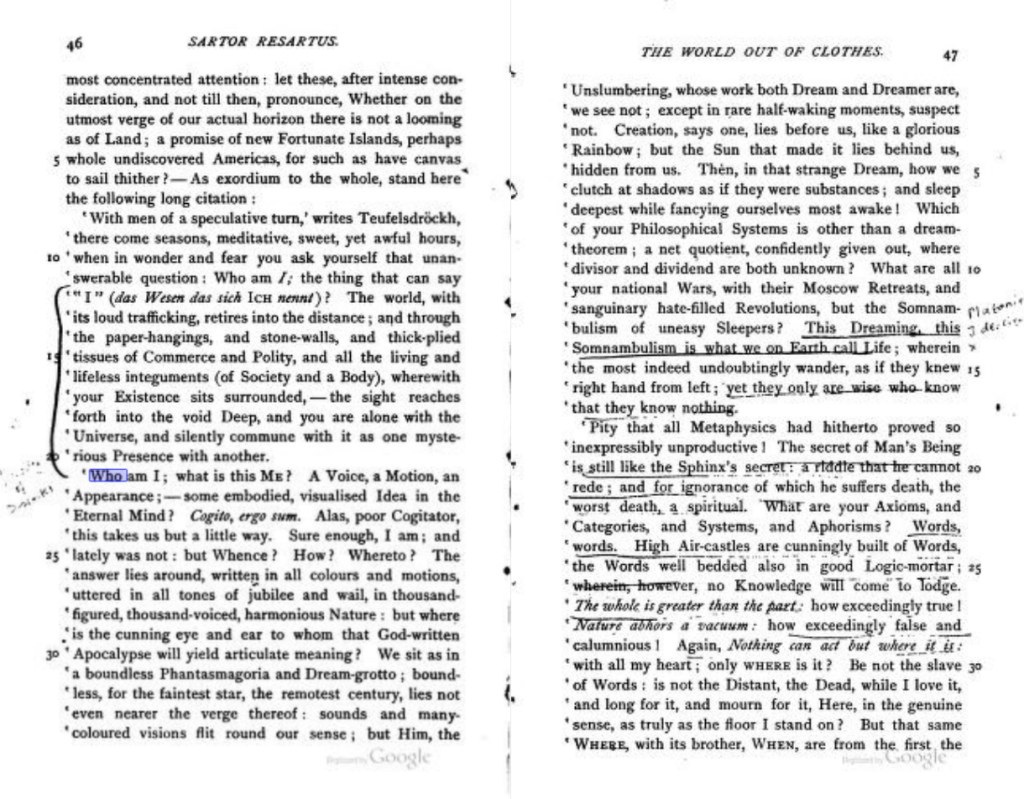

Gauguin’s medley of sources included literary references such as Sartor Resartus by Thomas Carlyle, which Gauguin owned. In chapter eight, “The World Without Clothes,” the philosopher questions the validity of a modern system of thought and imagines an undiscovered America in which new philosophical questions can be posed. He asks, “Who am I; what is this Me? A Voice, a Motion, an Appearance;—some embodied, visualized Idea in the Eternal Mind? Cogito, ergo sum … The answer lies around, written in all colours and motions, uttered in all tones of jubilee and wail, in thousand-figured, thousand-voiced, harmonious Nature… We sit as in a boundless Phantasmagoria and Dream-grotto… the Canvas (the warp and woof thereof) whereon our Dreams and Life vision are painted.”

Gauguin’s Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going? appears to visualize these questions in many colours and painted on coarse sackcloth. But his subject is also rooted in biblical and Polynesian creation narratives. The figure at the near center reaching for the fruit from the Biblical tree of knowledge is an androgyne. They possess spiritual purity. Tahitian culture has long included an established place and role for a third gender, the feminine male, and this figure may be interpreted as māhū. Mario Vargas Llosa describes the māhū in “The Men-Women of the Pacific Paul Gauguin II ” ( Tate Etc. no 20 (Autumn 2010)

( https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-20-autumn-2010/men-women-pacific):

When Gauguin arrived in Tahiti for the first time, in June 1891, he had his hair down to his shoulders, wore a cockade with red fur, and his clothes were flamboyant and provocative. He had dressed like this ever since he had given up his career on the Stock Exchange in Paris. The indigenous people of Papeete were surprised at his appearance and believed he was a mahu, a rare species among the Europeans in Polynesia. The colonists explained to the painter that, in the Maori tongue, the mahu was a man-woman, a type that had existed from time immemorial in the cultures of the Pacific, but which had been demonized and banned by common consent by both Catholic and Protestant missionaries, engaged in a fierce battle to indoctrinate the native peoples, during the intense period of colonization in the mid-nineteenth century.

However, it was proved well-nigh impossible to root out the mahu from indigenous society. Concealed in urban settlements, the mahu survived in the villages and even in the cities, and re-emerged when official hostility and persecution abated. Proof of this fact can be found in Gauguin’s paintings in the nine years that he spent in Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands, which are full of human beings of uncertain gender who share equally masculine and feminine attributes with a naturalness and openness that is similar to the way in which his characters display their nakedness, merge with natural order or indulge in leisure.

…

It is risky to translate mahu as homosexual because, even in the most permissive societies of our age, homosexuality is still surrounded by prejudice and discrimination. Such prejudices did not exist among the Polynesians before the emissaries of Christian Europe censored a practice that, before their arrival, was recognized and universally accepted as a legitimate variant of human diversity. The extraordinary sexual freedom of the Maoris of the islands has been subject to countless studies, testimonies and caricatures ever since the first European ships reached these islands of paradisiacal beauty. Only now that western society has gradually made sufficient advances to allow similar sexual freedom and tolerance to that enjoyed by Polynesian cultures can we realize how civilized and lucid these small Pacific Maori communities were, at a time when the powerful West was still mired in the savagery of prejudice and intolerance. It was not just a question of sexual freedom; there was also the widespread practice among native communities of adopting orphaned or abandoned children, a custom that is still maintained. (Mr Tetuani of Mataiea, where Gauguin lived for several months, had 25 adopted children.)

The mahu might be a practicing homosexual or remain chaste, like a girl making a vow of chastity. What defines them is not how or with whom they make love, but that, having been born with the sexual organs of a man, they have opted for femininity, usually from childhood, and that, helped by their family and community, they have become women, in their way of dressing, walking, talking, singing, working and often, but clearly not necessarily, of making love.

The blue idol is said to represent the goddess Hina who Gauguin mistakenly assumed had great significance in Tahitian cosmogony.

7.10

| Exoticism, Eroticism, and Spirituality

Cardinal argues that Gauguin searched for deeper meaning by engaging with mysterious signs and icons in his paintings. In Tehamana Has Many Parents, for example, he inserts a cryptic band of lettering on the wall behind Tehamana, an inscription in rongorongo writing from Easter Island, which Gauguin had copied and kept. What bearing it has on the painting itself is still being determined. However, seen in tandem with other markings and the title, Cardinal suggests that Gauguin was striving to convey the essence of Maori culture,

…he had gained access to a pan-Pacific native culture and could begin to see himself engaged in serious ethnographic research… He had a genuine curiosity about Oceania and the Maori people at large, studying their accomplished artefacts during a brief stay in Auckland and reading up on their legends and ancient customs. His own totemic carvings may be pastiches of Maori models, yet they reflect a serious commitment and have a dignity and presence of their own. What Gauguin seems to be arguing is that there exists in the Pacific a tradition of spiritual involvement in the natural world, and that this links its inhabitants to a past and present system of tacit meanings.

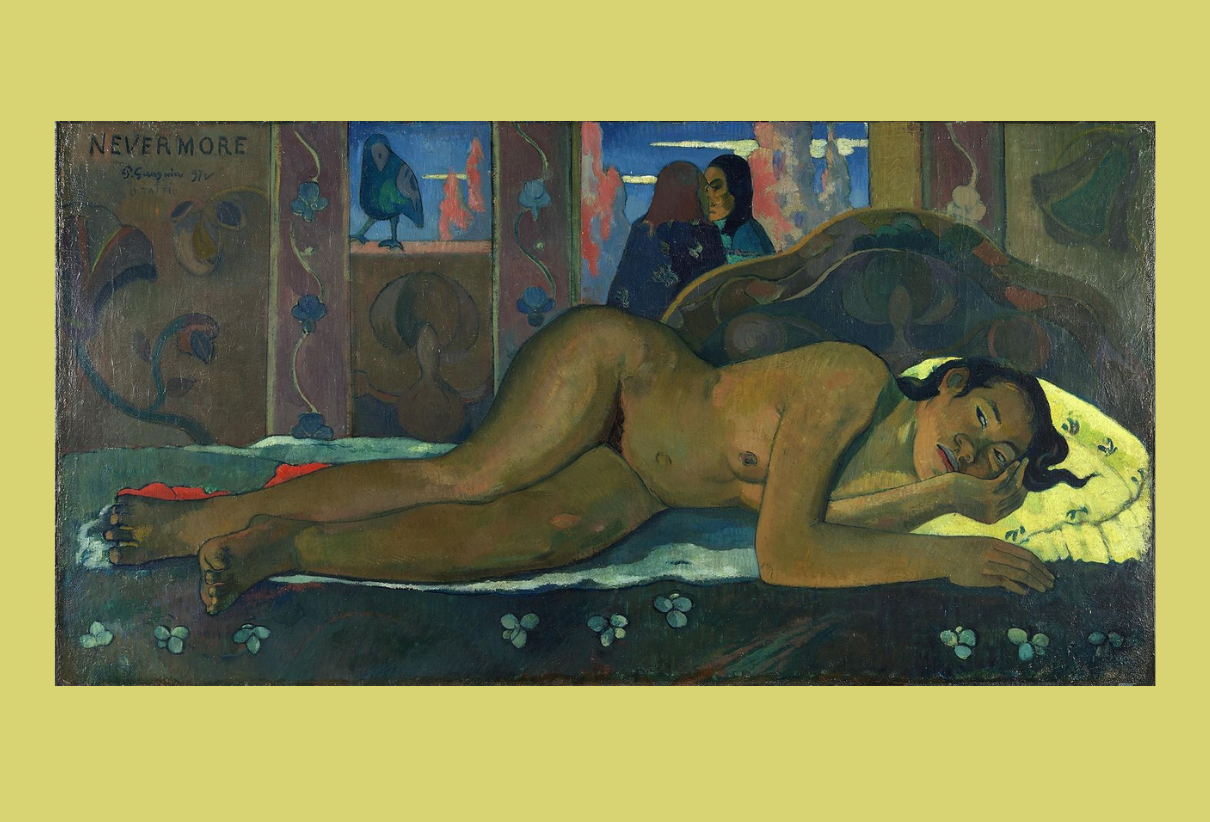

Gauguin’s preoccupation with the spirituality of Tahitian culture can be seen in his frequent inclusion of supernatural beings in his works, as in Spirit of the Dead Watching or Nevermore.

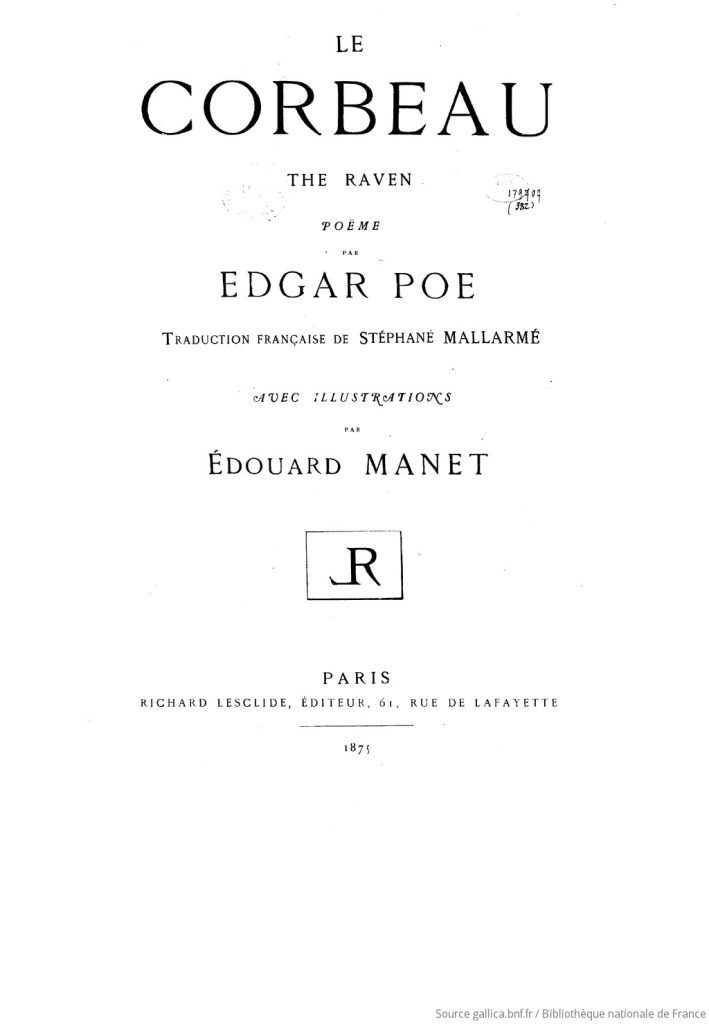

Nevermore may depict the reclining nude image of Gauguin’s fifteen-year-old mistress Pahura. A sense of unease permeates the scene. The darkness of the interior, in contrast to the bright skies seen through the windows in the background, reinforces the occult mood. A large raven which perches on a sill staring inwards is an allusion to Poe’s Gothic poem The Raven, which Gauguin knew from Stephane Mallarmé’s translation. Its presence suggests Gauguin’s deliberate attempt to incorporate a western touchstone and engage with a European audience through “cross-cultural citation.”

Vojtěck Jirat-Wasiutyńsi writes in “Paul Gauguin and Edgar Allan Poe’s “Philosophy of Composition” (RACAR : Revue d’art canadienne /Canadian Art Review 1 no. 1 (1974): 61-62):

In emphasizing the freedom of the creative artist vis-à-vis nature and the calculated, rational aspect of the creative process, Gauguin used the example of Poe’s Raven. He was echoing Poe’s own explanation of the composition of the poem given in “The Philosophy of Composition” … Gauguin alluded to the raven as a literary parallel in order to emphasize the artist’s choice and his calculation of effects on the basis of pictorial appropriateness and probability.

But he was also surely attracted to the Raven in connection with the discussion of shadows because of Manet illustration of the passage, “And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor/Shall be lifted — nevermore !” came to mind; here the shadow was used with calculated “strangeness’. Gauguin may have been familiar with the Manet illustrations which were published in 1875 and again in 1888 and 1889.” (Poe chose the raven image in his poem because in many cultures the raven is associated with death. The bird’s quote, “nevermore,” refers to the fact that the narrator will never again see or forget the dead Lenore).

7.11

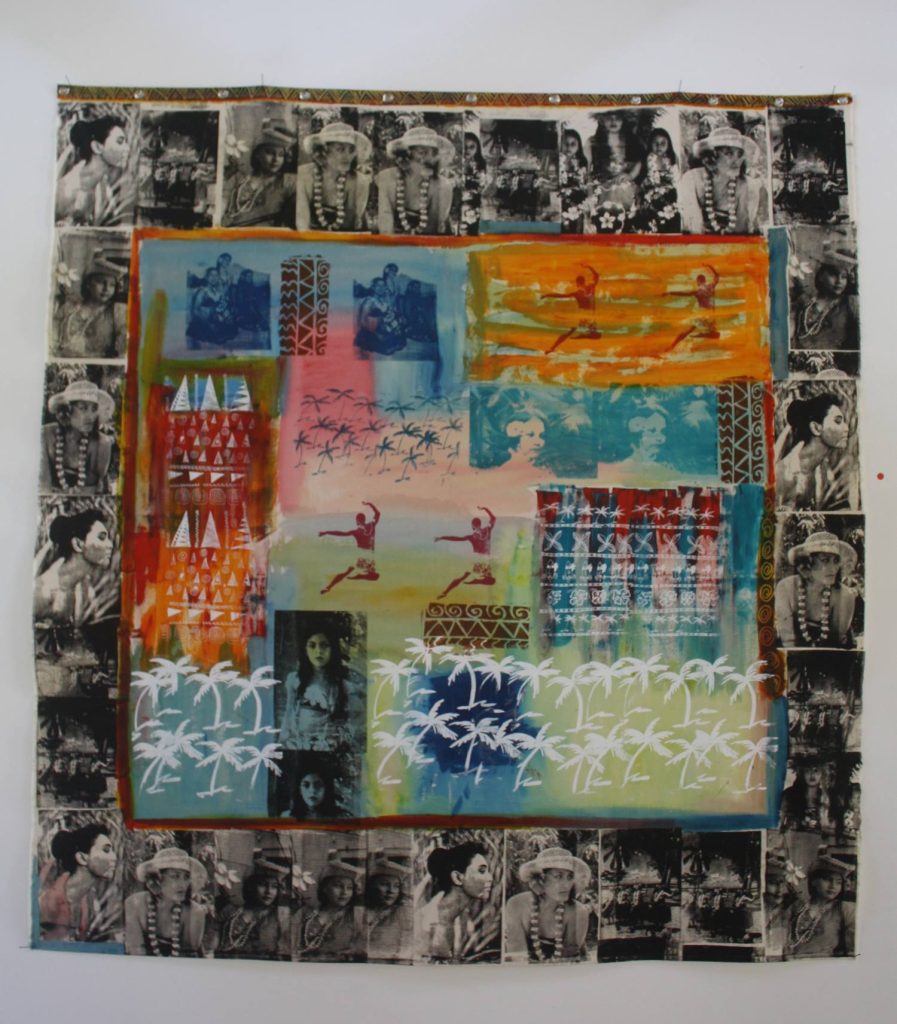

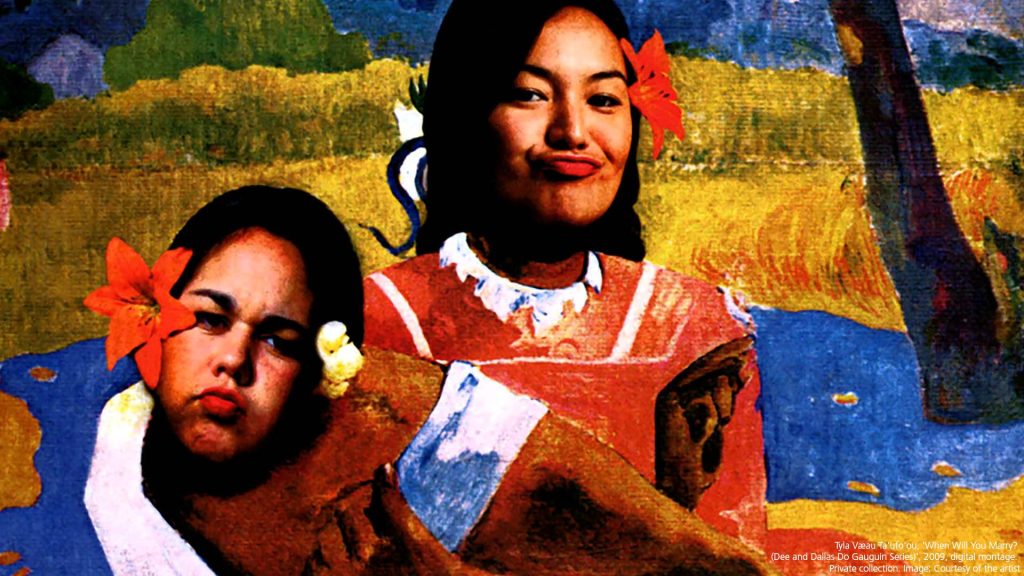

| Critical Conversations

Norma Broude, a feminist scholar of 19th-century European art, has addressed the divergence of opinion that inevitably accompanies Gauguin’s work in the twenty-first century. As quoted in Meredith Mendelsohn “Why is the Art World Divided over Gauguin’s Legacy?” (Artsy August 3, 2017, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-art-divided-gauguins-legacy) on the one hand, Broude says, is Gauguin’s “perennial popularity in the art world, fueled by aesthetically focused exhibitions that appear with regularity in major museums worldwide,” and on the other is the “mistrust and even abhorrence with which a segment of the academic world, unable to move beyond earlier feminist and post-colonialist critiques, continues to regard him and his oeuvre.”

To enlarge upon the multiple issues arising from a redressing of Gauguin’s life and oeuvre, we look to excerpts from Norma Broude’s introductory essays to Gauguin’s Challenge: New Perspectives After Postmodernism (https://www.bloomsburycollections.com/book/gauguins-challenge-new-perspectives-after-postmodernism/introduction-gauguin-after-postmodernism?from=search)

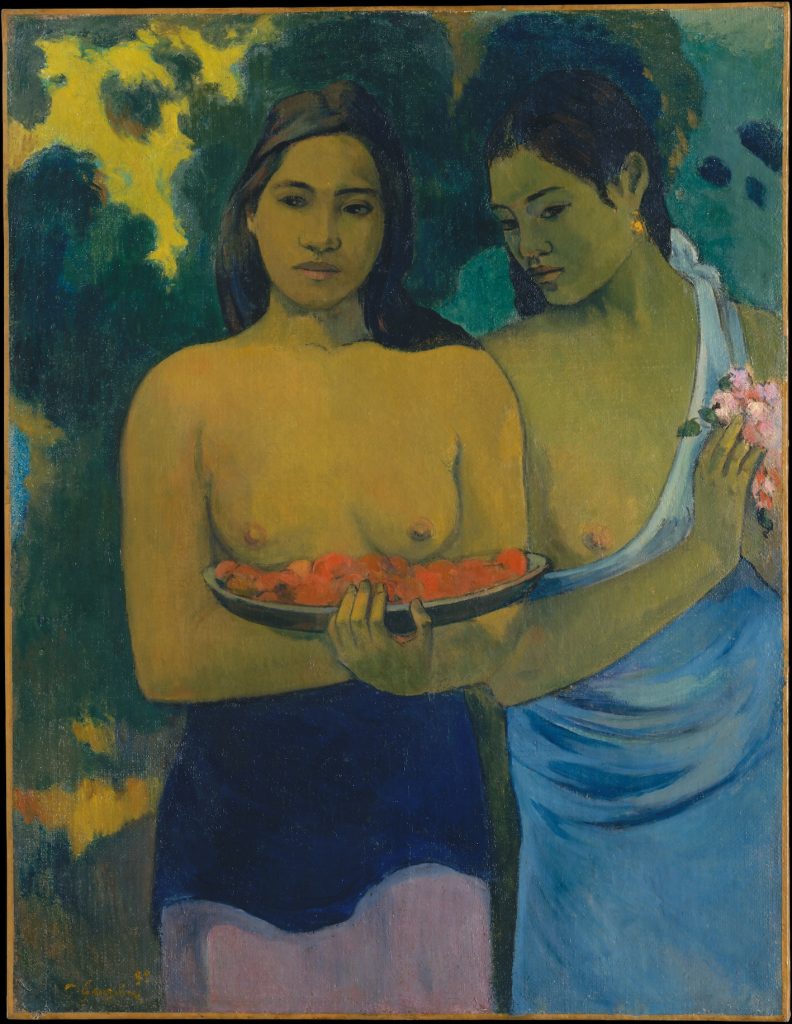

As Broude states in her introduction, in the late twentieth century, Paul Gauguin became “an artist whom feminist art historians loved to hate.” The salvo was spurred by Linda Nochlin’s analysis of the artist’s Two Tahitian Women in 1972, where the two women “offer their breasts to the viewer along with the platters of ripe mangoes that they hold.”

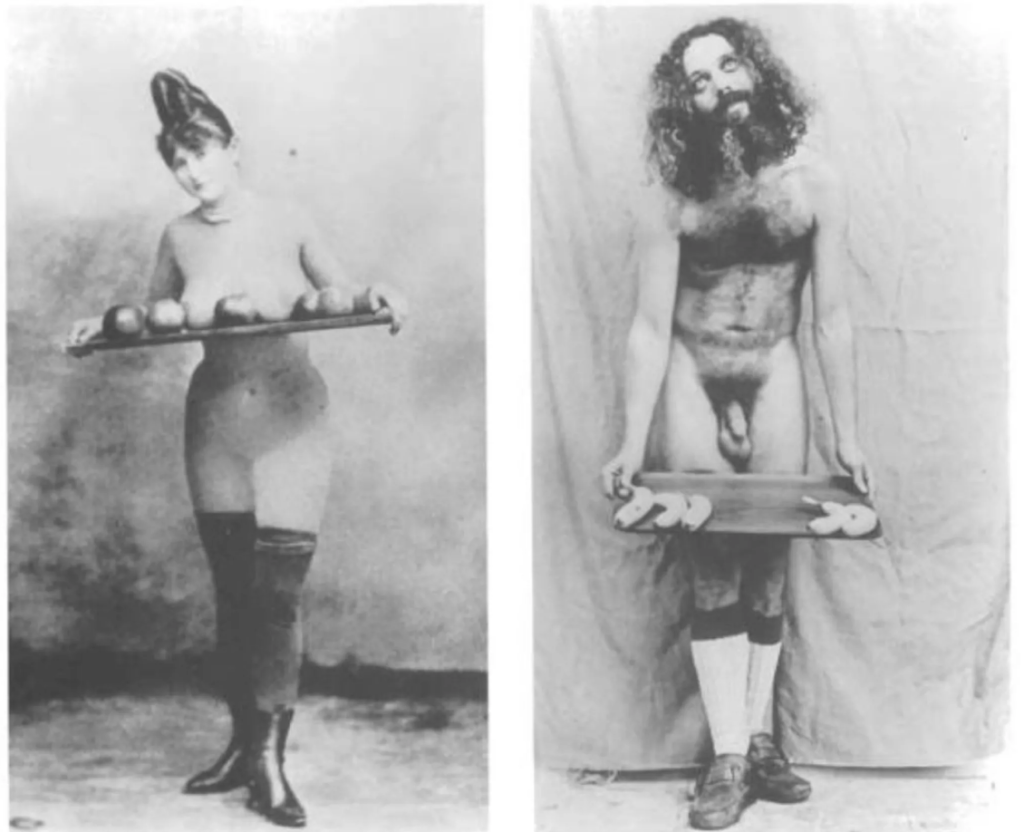

Nochlin famously juxtaposed this painting with her own mock-pornographic photograph of a nude male model, posing with a platter of bananas beneath his genitals and exhorting the viewer, through the caption, to “buy my bananas.” Using sexual reversal, a powerful weapon of early feminist analysis, Nochlin’s visual joke exposed the gendered operations of the gaze in “high art,” and it was a wake-up call for emerging feminist art historians in the early 1970s. It was also a turning of the lens that told us perhaps as much about ourselves as it did about Gauguin: about the extent to which women as well as men in the twentieth century had come to accept the sexualized and possessive gaze of the male upon the body of the female as integral to the patriarchy’s definition of high art and universal cultural greatness.

This awakening, however, and the subsequent revelations it engendered did little to alter Gauguin’s place in the mainstream canon, if judged by the steady stream of major exhibitions that have continued to appear down to the present day. But it did lead at the time to a vehement rejection and repositioning of Gauguin in the feminist art-historical literature, where he soon came to be castigated, as much for his life as his art, in terms of late-twentieth-century standards and moralities in general and in terms of feminist and postcolonial ones in particular.