Chapter Three

FEMALE LABOUR &

Prostitution in Paris

CONTENTS

Introduction

3.1

Framing the Female Figure: Debauchery and Decorum in 19th-Century Art

3.2

Avant-Garde Painters and the Subject of Prostitution

3.3

3.4

Anonymity, Identity and the Parisian Prostitute

3.5

Female Spectacle:

Photography, Theatre and the French Courtesan

3.6

3.7

3.8

3.9

The Travails and Tragedies of the Ordinary Prostitute

3.9

Covert Prostitution: Shopgirls and Serveuses

3.10

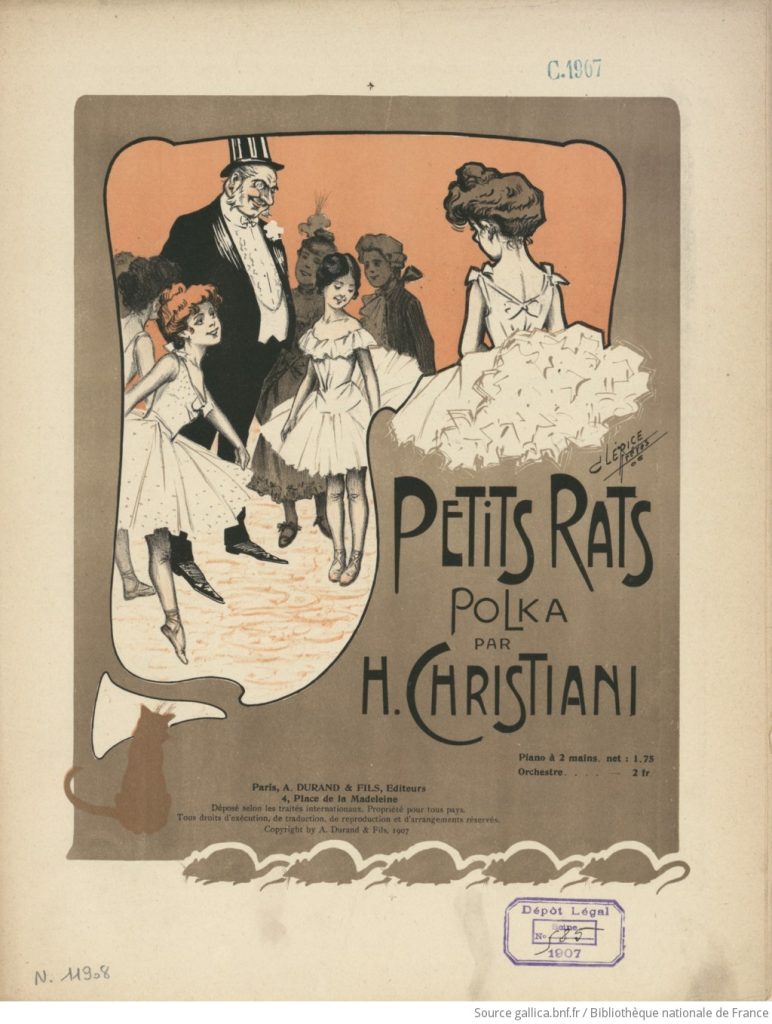

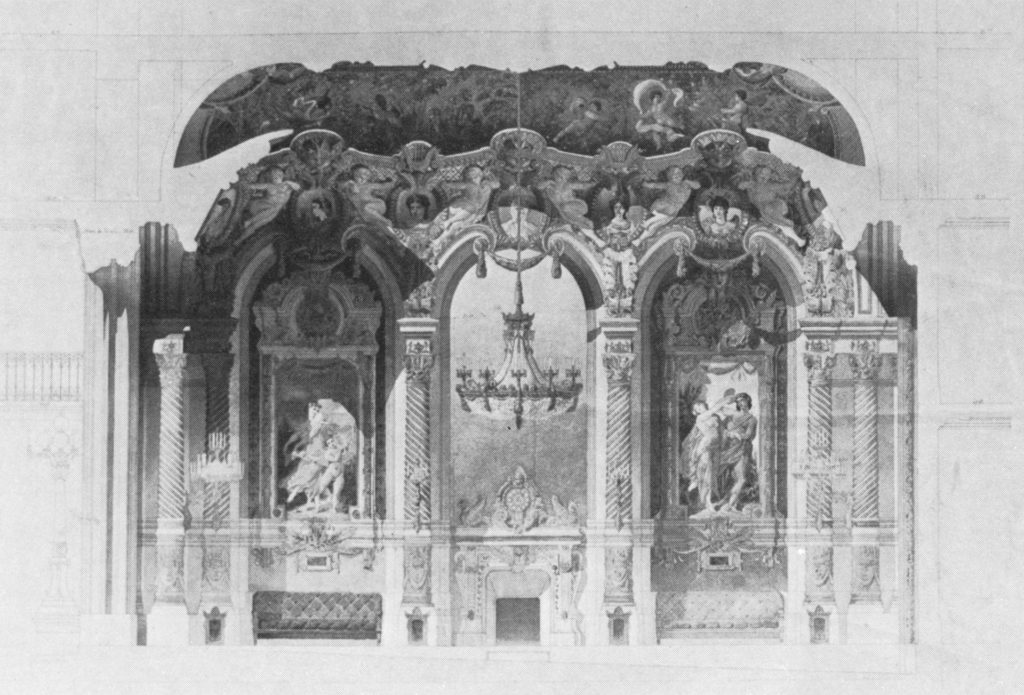

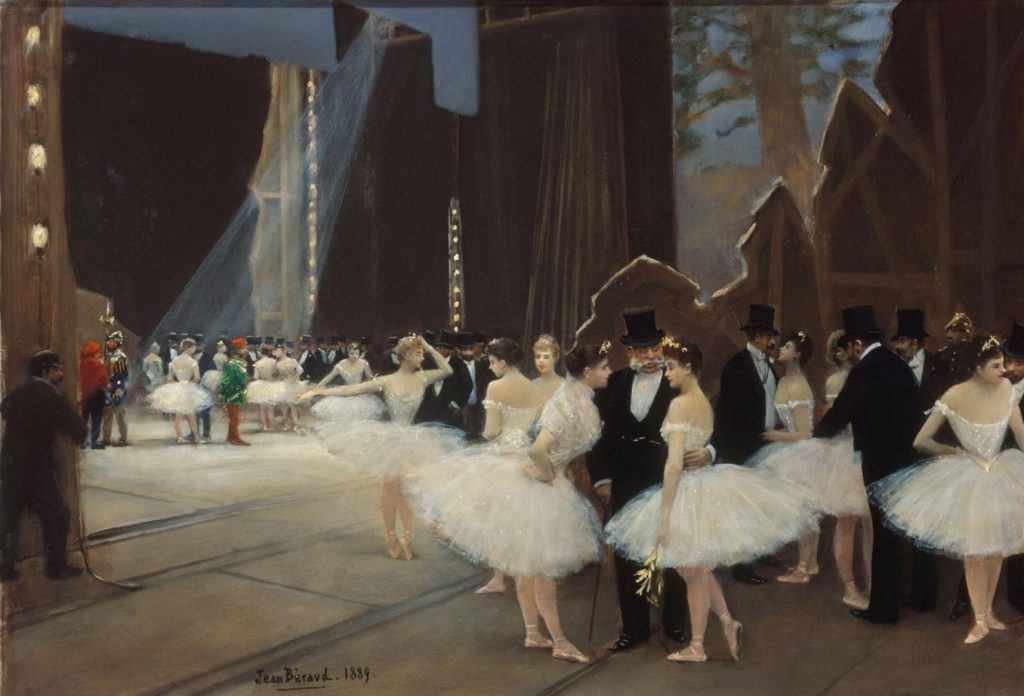

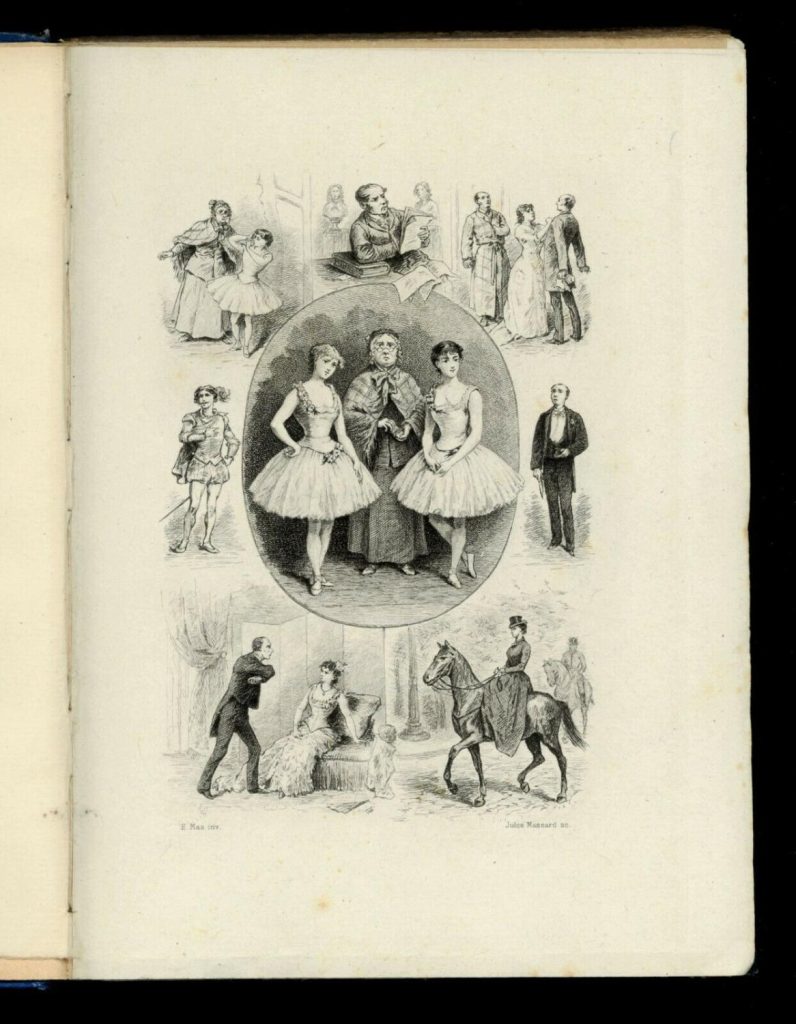

The Paris Opéra: “The Brothel of France”

INTRODUCTION

The painters of modernity were driven to find their subjects in the everyday world that surrounded them, exploring sites ranging from bourgeois leisure spaces to the brothels and bars of the city. Central to their artistic endeavor was the commitment to observe and depict their world without conventional filters. Given this approach, it is not surprising that female prostitutes, who were becoming increasingly visible in the social landscape of Paris during that period, featured prominently as subjects in their works. The avant-garde artists of the time sought to capture the raw and unfiltered aspects of contemporary urban life, and the presence of prostitutes became a poignant and often controversial element in their portrayals.

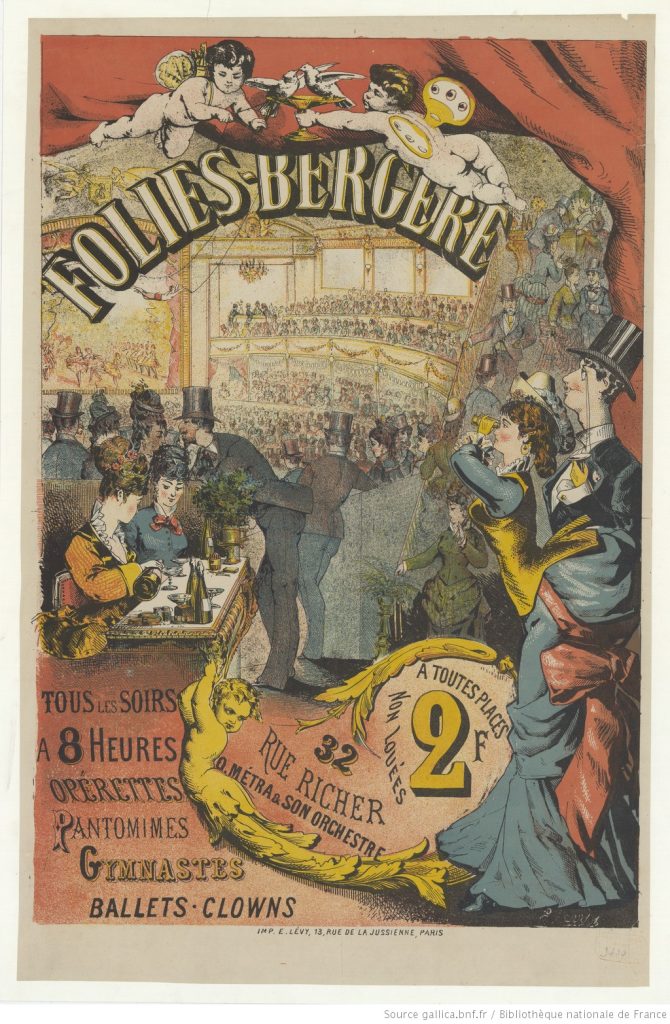

In the rebuilt Paris, spaces of bourgeois entertainment and social exchange created new opportunities for prostitutes, who quickly became a visible part of the everyday fabric of the city. They conducted business in cafés, concert halls, theatres, and brasseries, eventually becoming associated with the very idea of urban modernity.

Avant-garde representations of women in nineteenth-century French art and literature rapidly reflected this new social reality, and artists who were ambitious to express their era elevated courtesans to bonafide subjects in their works.

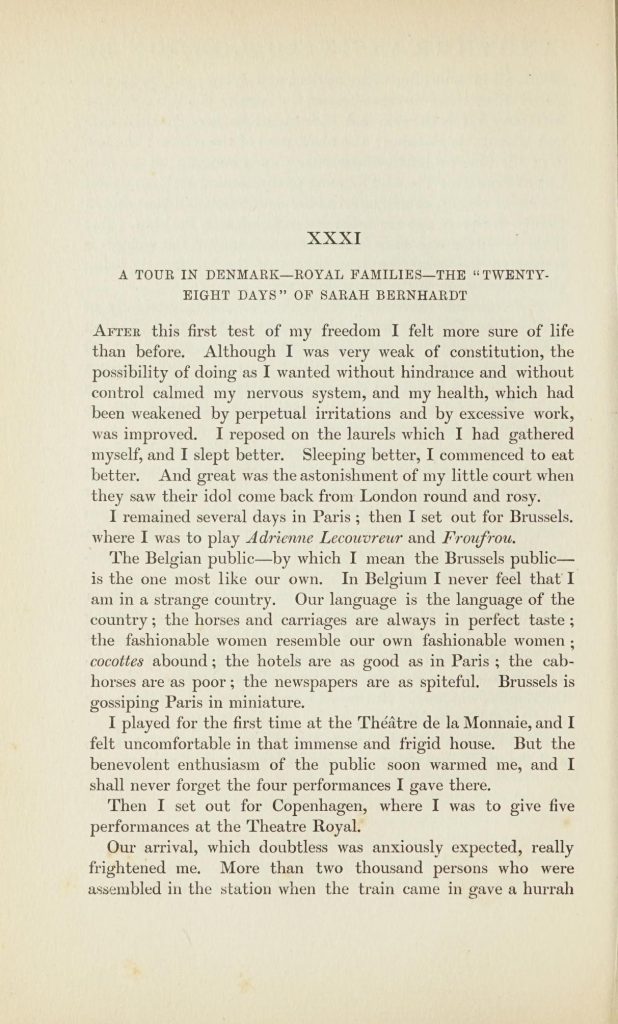

Richard Thomson Watson Gordon, curator of Splendor and Misery: Images of Prostitution 1850-1910 (Musée d’Orsay, 2015-2016), explains:

Every major [male] artist at the time tackled the subject of prostitution in one way or another…It was a subject that interested them. Why? The obvious answer is that they were men, but another reason was that prostitution was linked to the idea of modernity. People had moved to the city, which was in itself a new concept, where the moral strictures of the village had disappeared. The city was fluid, and this excited the artists.

Prostitutes ranged from filles en carte (registered prostitutes), filles insoumises, unregistered girls soliciting in public places, verseuses, women working as waitresses in brasseries à femmes, and courtesans, the kept mistresses of the wealthy elite. Although prostitution was considered morally wrong, it was tolerated as a societal necessity.

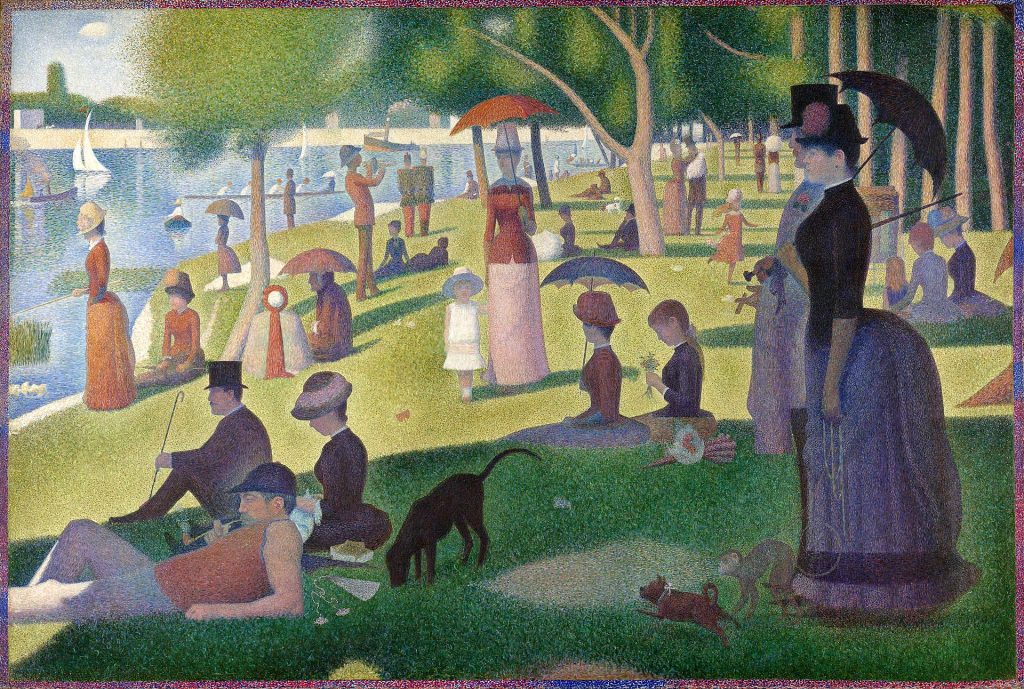

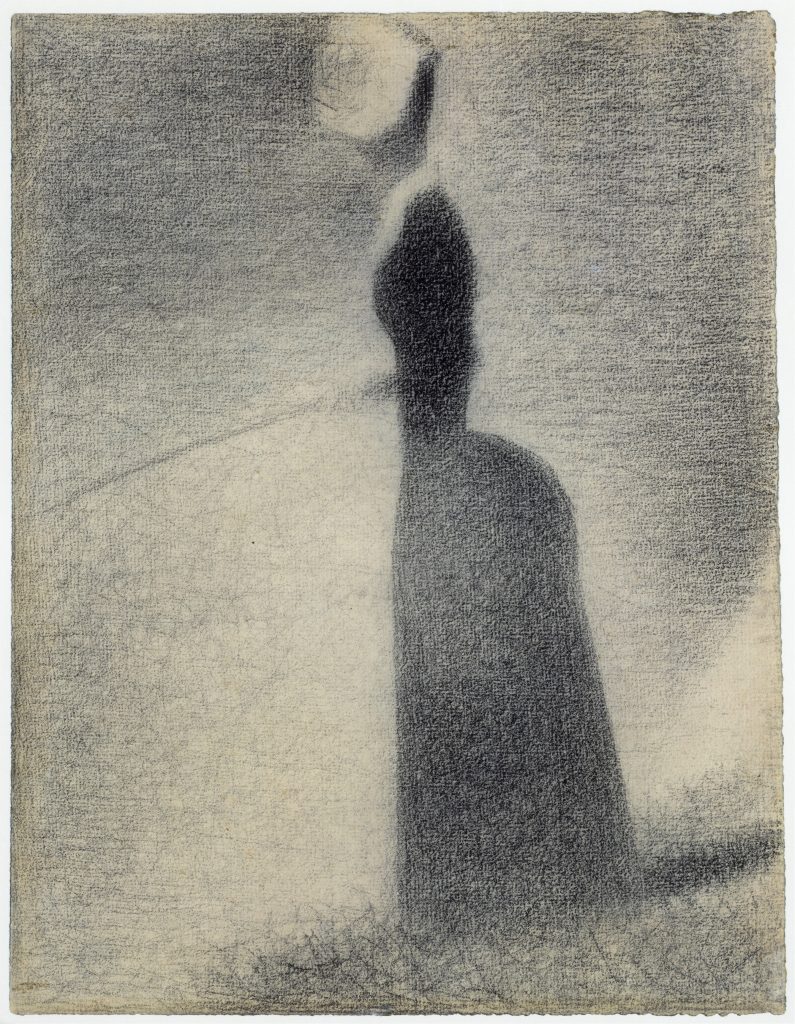

This chapter will explore the evolving depictions of the female prostitute by avant-garde artists, including Courbet, Manet, Degas, Cézanne, Toulouse-Lautrec, Tissot, and Seurat. It will analyze their diverse thematic and stylistic approaches, considering how the approach to the subject changed over time. The examination will provide contextual analysis from both a historical and art historical perspective, shedding light on the broader social, cultural, and artistic dynamics that influenced the representation of the female prostitute in the works of these influential avant-garde figures.

3.1

| Framing the Female Figure:

Debauchery and Decorum in 19th-Century Art

Gustave Courbet’s Young Ladies Beside the Seine portrays two young women lounging on the grass by the river. The foreground features a brunette who seems to be waking from a nap, wearing white clothing reminiscent of undergarments. She looks out at the viewer with a drowsy expression. In the background, a fashionably dressed blonde gazes into the distance, her head resting on her gloved left hand. This painting, with its overtly sexual undertones, was perceived as a challenge to contemporary sensibilities, prompting strong criticism and condemnation.

Champfleury, in particular, expressed his disapproval, suggesting that Courbet had lost his way as an artist: “As to the Young Women, horrible! Horrible! Certainly, Courbet knows nothing about women. You’ll think me embittered. I’ve always told you that since Burial our friend has gone astray. He has kept his finger too much on the pulse of public opinion” (Jack Lindsay, Gustave Courbet: His Life and Art, London: Harper and Row, 1973, 151). Champfleury’s critique reflects the controversy surrounding Courbet’s departure from conventional artistic norms and his willingness to confront societal taboos in his work.

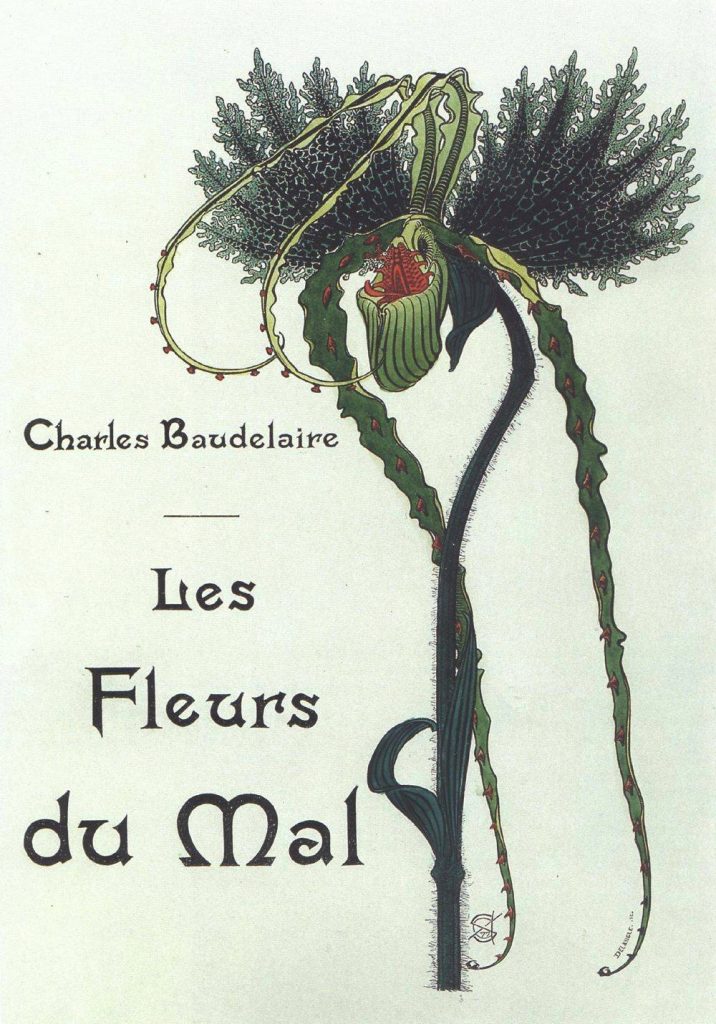

The dark-haired girl’s state of undress, the absence of a male subject, and the sexually provocative composition suggest a lesbian encounter. At the time, the term ‘lesbian’ was not specific to homosexuality. Females were called lesbian, tribade, gougnotte, lorette, sapphienne, petites soeurs, les deux amies, or la fleur du mal if they rejected socially inscribed roles of wives and mothers. Women who chose political or intellectual pursuits or participated in revolutionary social activities were considered lesbians. It was commonly believed that prostitutes were inclined to lesbianism.

The young women here, therefore, were easily read as lesbians and prostitutes. The drowsy closeness of the women lying side by side, the excessive display of garish garments and the enormous bouquet were the overt signs of lesbian eroticism, which shocked the public when the painting was first exhibited.

Linda Nochlin in “Courbet’s Real Allegory: Rereading the Painter’s Studio” (in Representing Women (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1999), 138) notes the symbolic intent of the shawl in Courbet’s The Young Ladies Beside the Seine:

Courbet’s representation of the white-clad fallen woman in the foreground of The Young Ladies on the Banks of the Seine…lends itself quite nicely to a pejorative reading within the codes defining nineteenth-century female decorum. Is it a mere coincidence that the gorgeously painted cashmere shawl in the foreground re-echoes the position and function – veiling yet calling attention to the sexual part of the body.

The shawl, Nochlin explains, signifies the immorality of the prostitute.

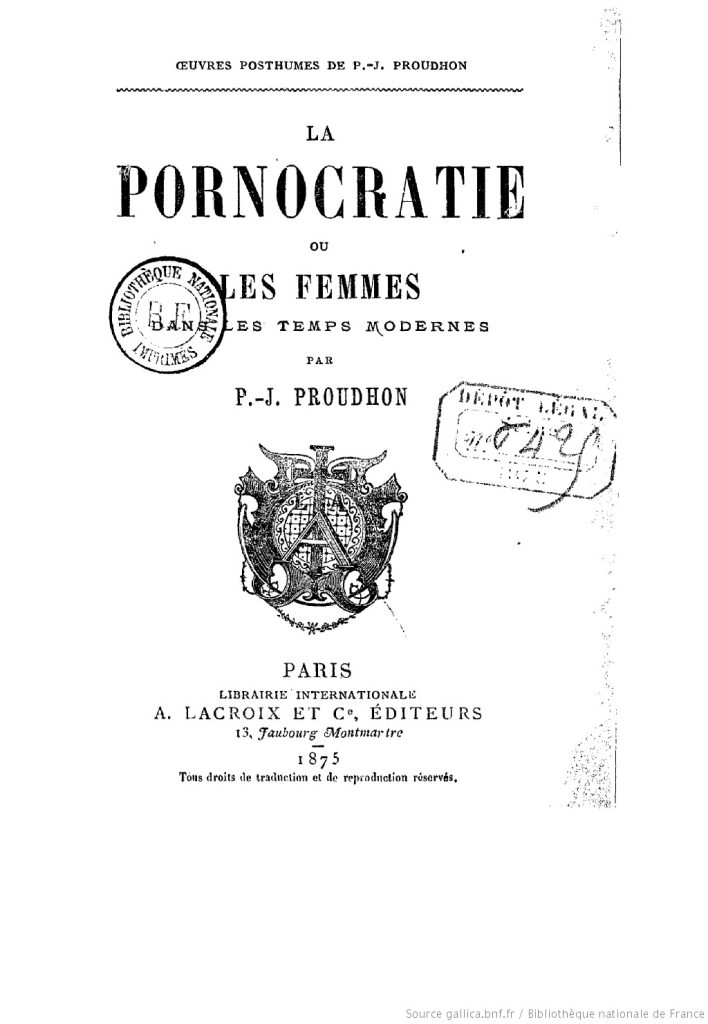

The diametric framing of the female figure as either virtuous or debauched was standard in writings of the era. Proudhon’s Pornocracy or Women in Modern Times (1875) extolled the virtues of the good woman, always a married female, but also claimed marriage as essential to the construct of social order. In essence, domestic virtue was equated with social goodness. Proudhon alleged that marriage supported moral behaviour and was the “mise-en-scène of social stability.” He argued that women who did not participate in the traditional marriage contract were morally bankrupt contributors to a debased society he termed a “pornocracy.” He believed immorality and corruption would follow if women were granted political involvement and social standing.

The separation of the male and female spheres — the woman caring for her children, the husband busy at work — is visually described in Alfred Stevens’ Family Scene or Domestic Happiness or All the Joys. The nurturing mother poses serenely, her head tilted lovingly towards the young child she holds on her lap. A flower in her hand symbolizes the purity and beauty of their natural bond. In the background, her husband is at his desk, surrounded by books, his back to the viewer. He is detached from the domestic scene, absorbed in his serious work.

3.2

| Avant-Garde Painters and the Subject of Prostitution

The allure of prostitution as a subject became widespread among avant-garde painters of modern life in the 1870s and 1880s, starting with Manet’s iconic work, “Olympia.” The prostitute, in the eyes of these artists, embodied the two antithetical qualities of modernity. On one hand, she represented the transient, ephemeral, and unstable aspects of contemporary life. On the other hand, she was seen as a fixed commodity, highlighting the commodification and objectification of women within the societal framework of the time. This dual nature of the prostitute as a subject served as a powerful metaphor for the complexities and contradictions inherent in the evolving modern urban landscape.

The phenomenon of the sexual marketplace, while intriguing, undoubtedly generated anxiety within the male population. This unease is hinted at in Paul Cézanne’s series of paintings created between 1870 and 1877, which, in part, served as a homage to Edouard Manet’s “Olympia” from 1863.

In Cézanne’s depiction, the nude figure is faceless and anonymous, positioned enthroned beneath a canopy. Surrounding her are a diverse crowd of men, including a painter, a bishop, and musicians, all seemingly paying homage to the female figure. This image is intended as a parody, mocking the veneration of sexualized womanhood and critiquing its societal consequences. Cézanne’s work reflects a commentary on the complexities and anxieties surrounding the portrayal and commodification of women in the evolving sexual landscape of the time.

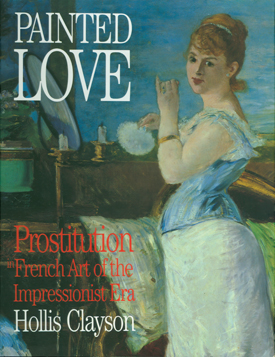

Hollis Clayson explains in Prostitution in the French Art of the Impressionist Era (Yale University Press, 1991, 44):

Although Cezanne’s quirky series seems to be an unusually transparent record of some of the doubts, worries, and fantasies of a bourgeois living through the changes in the sexual economy in the big city, it also introduces one of the trademarks of the avant-garde project as it took shape during this period: the effort to contain and order the anxieties provoked by the modern sexualized woman in general and by the contemporary prostitute in particular… Cezanne seems to have found the theme of the luxury prostitute (the woman of The Eternal Feminine fits that definition well) appropriate to his increasing pessimism (or even cynicism) about finding “real” eroticism in its old fantastic forms in the modern world.

A Modern Olympia was shown in the first Impressionist exhibition in the spring of 1874. “Critics found it to be a deeply disturbed and disturbing painting,” writes Clayson (17, 19).

The champion of naturalism, Jules Castagnary, for example, found that the picture was spoiled by fantasy and romanticism, both utterly personal in origin and therefore anathema to Castagnary: “From idealization to idealization, they will end up with a degree of romanticism that knows no stopping, where nature is nothing but a pretext for dreams, and where the imagination becomes unable to formulate anything other than personal, subjective fantasies, without trace of general reason, because they are without control and without the possibility of verification in reality.” Emile Cardon did not like Cezanne’s painting either, because he worried that the public might wrongly take the product of a disturbed artist as a seriously intentioned work: “One wonders if there is in this an immoral mystification of the public, or the result of mental alienation that one can do nothing but deplore.”

The critics supposed that Cezanne disclosed his own uneasiness with nudity and prostitutes. Eventually, his considerable discomfort with the imagery led him to set the subject aside.

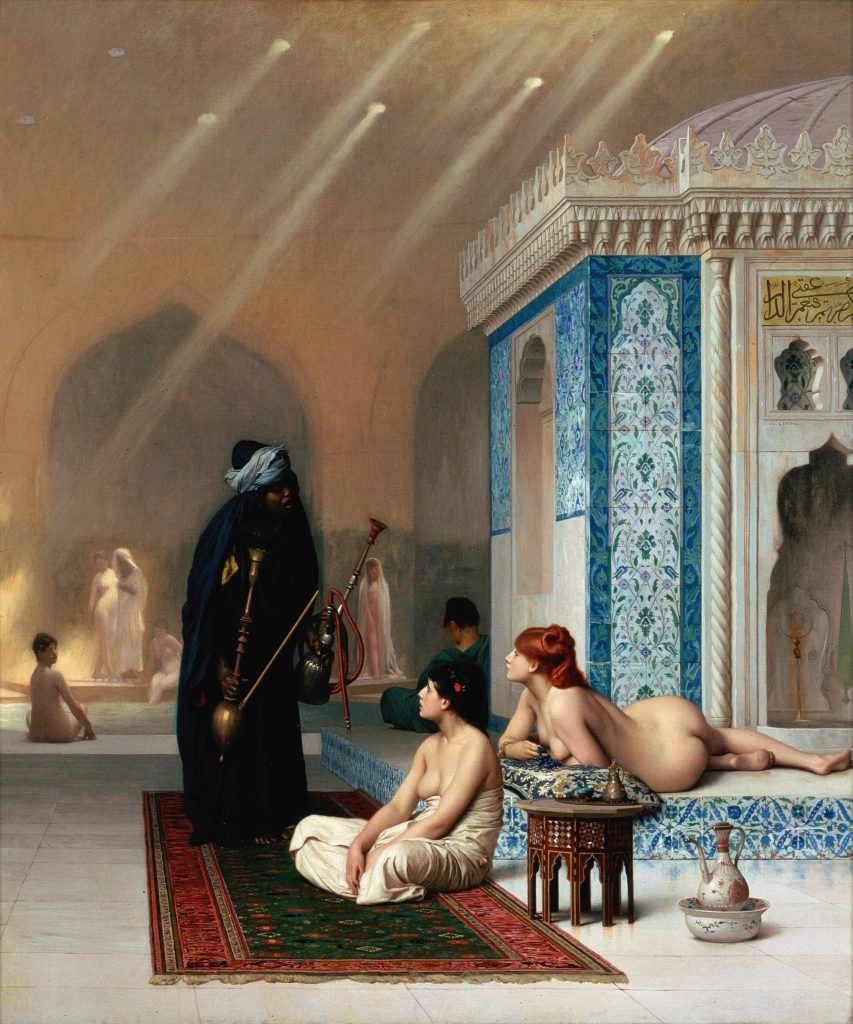

Academic nudes differed significantly from the treatment of the subject matter by artists of the avant-garde. Jules Lefebvre’s Odalisque provides a typical example of conventional nudes of the late 1870s. The painting is at once seductive and chaste. A perfectly painted nude in this context was, according to T.J. Clark, “a picture for men to look at, in which Woman is constructed as an object of somebody else’s desire.” (The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers, Princeton University Press, 1999, 131)

>Lefebvre’s title and the painted setting, which is replete with rich textiles, succulent fruits, and exotic objects, suggest that she is an enslaved woman or a concubine in a Turkish harem. This imagined place would have been in a separate part of a Muslim household reserved for a man’s wives, concubines, and female servants. The work appealed to the sexual and oriental fantasies of male visitors to the Salon. The model’s perfect body, and the seductive beauty of the scene, were meant to stimulate male passion while also providing painterly visual pleasure.

The scene presented is a harem, not a brothel, an exotic yet safe place of male privilege. A European invention, the harem was about the possession of prized objects. Placed in an oriental out-of-the-ordinary setting, the nude is at a remove, on display, passive and available, both to the unseen client and, by extension, the viewer.

3.3

| Fashion and the Courtesan

A distinct contrast in treatment and tone exists between the depictions of odalisques by artists like Lefebvre and the portrayal of prostitution as addressed by Manet and his circle. Notably, in Manet’s works, such as “Nana,” there is a departure from the traditional rendering of undressed or veiled women.

In “Nana,” for instance, the titular subject is not undressed, and she directly engages the viewer’s gaze. Clad in a white chemise, a blue corset, silk stockings, and high-heeled shoes, Nana looks calmly at the observer. Meanwhile, a top-hatted man sits off to the side on a burgundy velvet settee. Despite his presence, the seated man is partially hidden and relegated to a secondary role in the narrative. This departure from the conventional representation of odalisques reflects Manet’s and his contemporaries’ distinct approach to the portrayal of women and themes related to contemporary urban life.

Manet paid meticulous attention to the expression of the young woman in “Nana.” She gazes towards the spectator with a certain insouciance, embodying a blend of flirtatiousness and flippancy. Nana is fully aware of her desirability, and her beauty commands attention and assessment. Her demeanor suggests a self-awareness as she engages the viewer while seamlessly continuing her self-adornment.

The theatrical positioning of Nana’s hands emphasizes her skilled application of makeup: her right hand delicately holds a powder puff, while the left, with pinky extended, clasps her lipstick. This pose accentuates her affectedness and artifice. Nana’s plump, curvaceous body and the sway of her back convey an air of immodest ease. The bird depicted on the wall, resembling Nana’s posture, holds significance. It is a crane, known as “grue” in French, a slang term for a prostitute. This detail adds a layer of symbolism, connecting Nana to the world of prostitution through visual metaphor.

Manet’s Nana visually recalls Baudelaire’s writings in “The Painter and Modern Life” (1863). Jeanne Willette explores Baudelaire’s concept of modernity and artificiality in “Baudelaire and ‘The Painter of Modern Life’ ” (arthistoryunstuffed, Aug 27, 2010):

For Modernism, fashion is the leading indicator of the “ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent,” for nothing is more changeable than fashion. Fashion stands for the new consumerism, showcased in the arcades, where commodities were protected in passages of iron and glass.” The woman becomes the carrier of artificiality. There is a slippage in Baudelaire’s writings from “women” to “prostitutes,” as if, for the poet there is no divide. It is known that his only relationship was with a prostitute, but that kind of connection was not uncommon, in an age where marriage was often a financial alliance. Baudelaire seemed to have no interest in the so-called respectable woman, who reflected her husband’s position and the values of the bourgeois society. The prostitute is a free and liberated woman, from the poet’s perspective and thus wears modernity as cosmetics and fashion, proclaiming the artificial. Indeed, the poet compares the application of makeup to the creation of a work of art: “Maquillage has no need to hide itself or to shrink from being suspected. On the contrary, let it display itself, at least if it does so with frankness and honesty.”

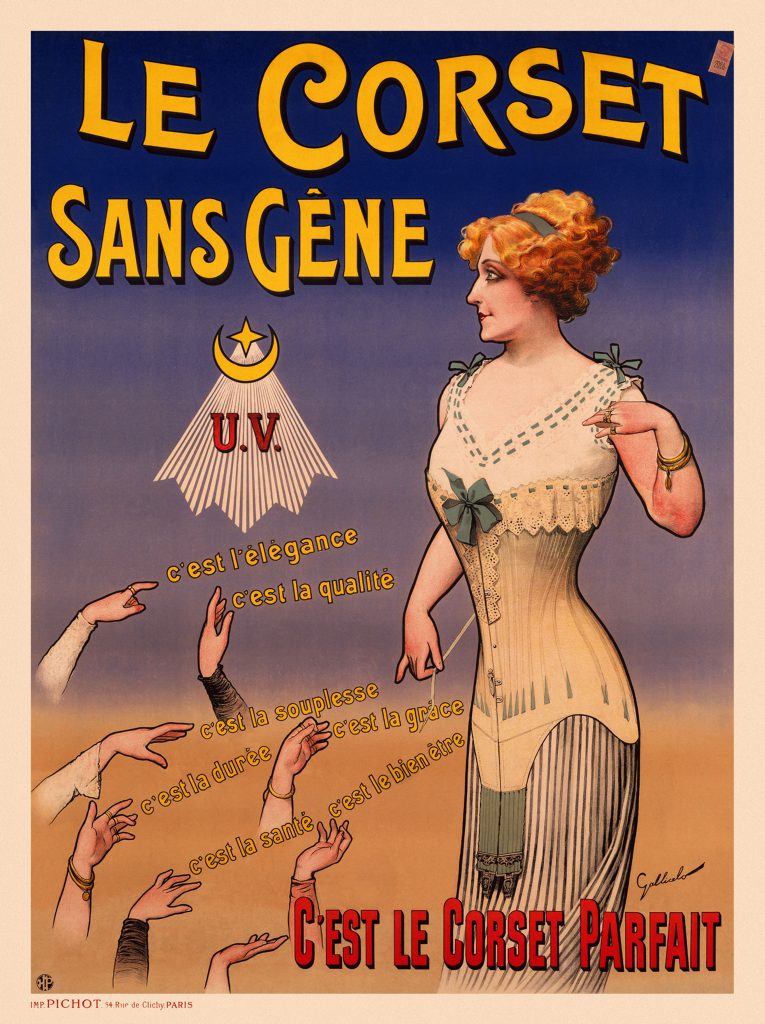

Manet’s Nana wears a satin blue corset, finely detailed in lace. Women of the era generally wore plain and neutral fabric corsets that were inexpensive. The elaborate, colourful corset eroticized by courtesans soon became the new fashion for the belles of French society, ranging from concubines to upper-class wives.

The fashions of famous courtesans were reproduced by designers and marketed to the bourgeois consumer. In this way, the sexualized garment trends of the courtesan were appropriated by respectable females. “Underneath layers of ‘respectable’ clothing, upper-class women had been infected by courtesan trends through their most intimate means of dress, their underwear.” (Holly G. L. Geary-Jones, “An Infectious Vessel: The Nineteenth-Century Prostitute Undressed,” Master’s thesis, University of Chester, 2017)

In all respects, Nana is symbolic of the female as a modern commodity; she is ‘for sale.’ The patiently waiting, formally dressed male client, by extension, stands for the buyer. While he is partially hidden, in all respects behind her, the equally anonymous viewer at whom Nana gazes is a customer as well.

“Nana” was a popular pseudonym in France for female prostitutes in the second half of the 19th century. The painting may reference Emile Zola’s Nana, a courtesan in his novel L’Assommoir (1877). Zola was interested in exploring deviant female sexuality, male sexual desire and extreme male discomfort. In the book, Nana is a pretty, poor, uneducated “jeune femme du peuple” (lower-class young girl). She is sensual to an unusual degree, and her early environment and alcoholism taint her. In time she becomes a monstrous courtesan.

Manet’s Nana was deemed indecent and was not accepted by the Salon of 1877. After its display in Giroux’s grand boulevard window in 1877, it was never shown again during Manet’s lifetime. In the few reviews of the painting that appeared in the press, commentators seized on Nana’s costume. Le Tintamarre published “Nana,” a four-stanza poem dedicated to Manet and signed “Un impressioniste.” Generally banal and moralizing, the poem describes it as Zola’s Nana, the second stanza reads: “More than nude, in her chemise, the fille shows off/Her feminine charms and the flesh that tempts./ There she is./ She has donned her satin corset and is getting dressed/ Calmly, near a man, who has come there to see her.” (Clayson, Painted Love, 76)

3.4

| Anonymity, Identity and the Parisian Prostitute

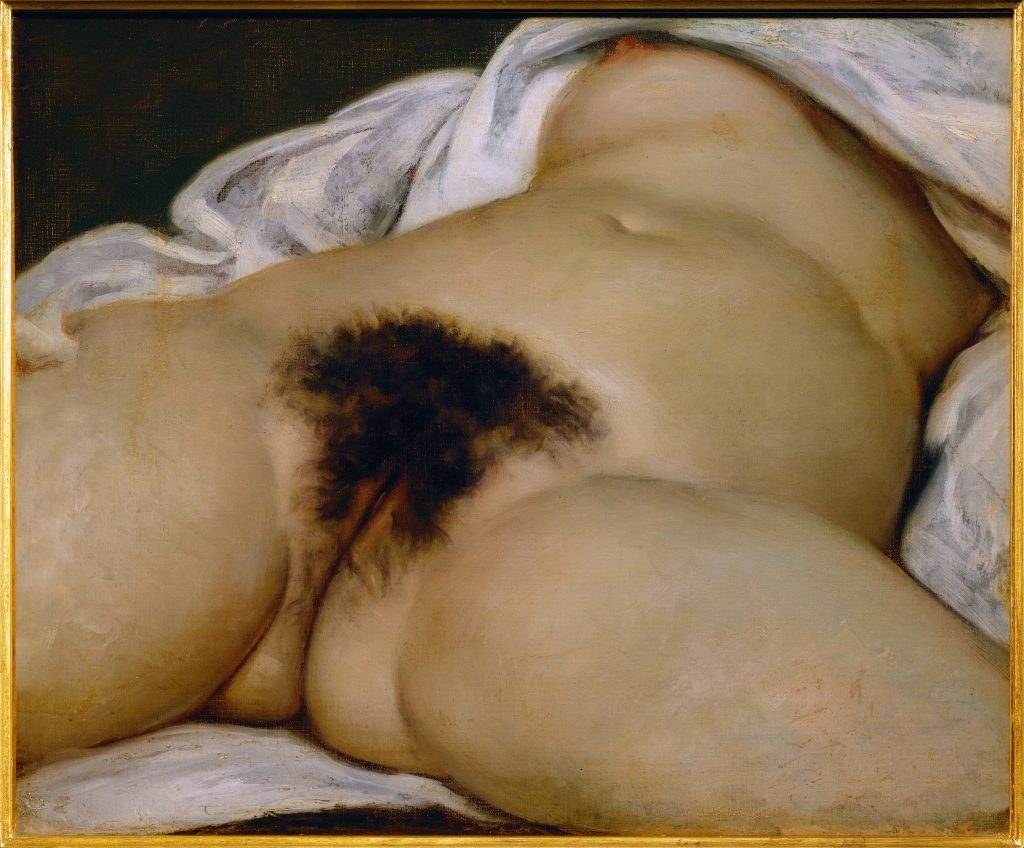

While the identity of the courtesan in Manet’s Nana remains unknown, the woman who posed for Courbet’s controversial The Origin of the World was identified in 2018. Before that, the painting was simply an anonymous portrayal of a female subject, more specifically, an image of the sex organ of the female, the site of male desire.

In 1880, the politician Léon Gambetta told the author Ludovic Halévy about encountering Courbet and seeing The Origin of the World at the home of the notorious art collector and Turkish ambassador to St. Petersburg, Khalil Bey (also known as Halil Şerif Pasha). Bey had commissioned the painting for his erotica collection. Gambetta described the painting as “a nude woman, without feet and without a head. After dinner, there we were, looking…admiring…We finally ran out of enthusiastic comments…This lasted for ten minutes. Courbet never had enough of it.”

Another reference to the work came from French writer and photographer Maxime du Camp in his four-column denunciation of the Paris Commune, Les convulsions du Camp (1889), an article originally published in Revue des deux mondes. He wrote:

To please a Moslem who paid for his whims in gold…Courbet…painted a portrait of a woman which is difficult to describe. In the dressing room of this foreign personage, one sees a small picture hidden under a green veil. When one draws aside the veil one remains stupefied to perceive a woman, life-size, seen from the front, moved and convulsed, remarkably executed, reproduced con amore, as the Italians say, providing the last word in realism. But by some inconceivable forgetfulness of the artist who copied the model from nature, had neglected to represent the feet, the legs, the thighs, the stomach, the hips the chest, the hands, the arms, the shoulders, the neck and the head.

In 2018 the French literary scholar Claude Schopp explained his accidental discovery that the model was the Opéra ballet dancer Constance Quéniaux. He read a letter dated June 1871 from Alexandre Dumas fils — the son of The Three Musketeers author — to George Sand, a French novelist and journalist, at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF, National Library of France). The erroneous transcription into English caught his attention. It read, “One does not paint the most delicate and the most sonorous interview of Miss Queniault [sic] of the Opera.” Upon closer inspection, Schopp realized that the word “interview” was actually “interior.”

When the dancer/prostitute /courtesan, Quéniaux retired at age 34, she won Khalil Bey’s affection. Schopp surmised that the sitter’s identity was concealed when Quéniaux ascended to Paris’s elite social circles. With the fortune she accumulated as a courtesan Quéniaux was well-off in later life. A dedicated philanthropist, she supported the Orphelinat des Arts, an institution for orphaned and abandoned children of artists.

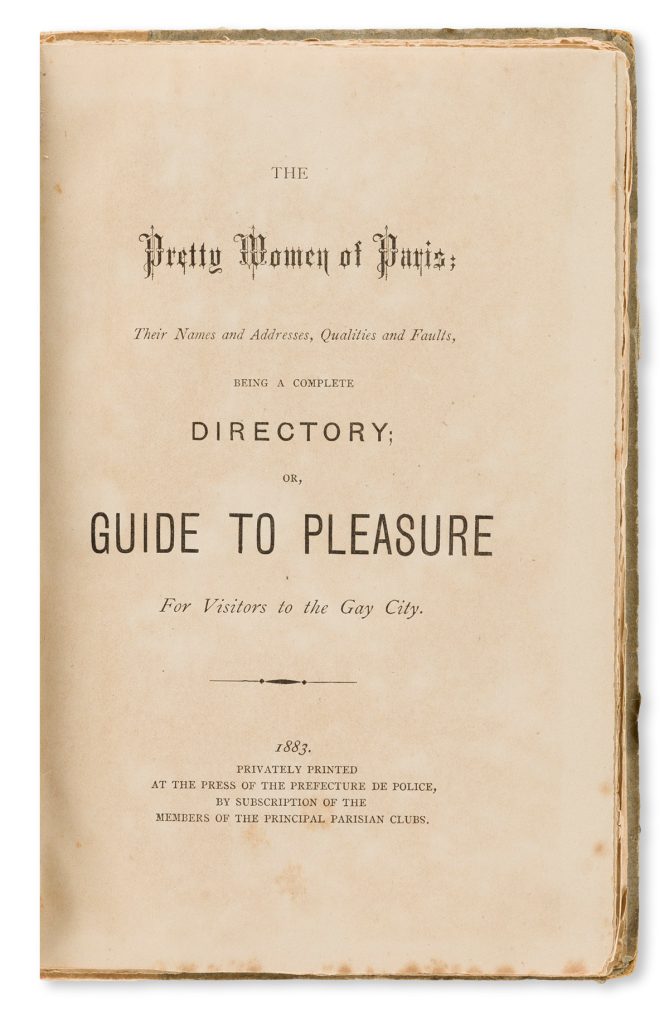

Written anonymously, probably by a wealthy British gentleman living in Paris, the purpose of The Pretty Women of Paris was to assist English men in locating prostitutes in the city. Only 169 copies of the 200-page “guide” were printed “for private distribution.” They included the names, addresses and photographs of the women; the following are a few examples:

Amélie Latour (pictured in 1870) was listed as living at 32 Avenue De L’Opera. She was praised as “one of the queens of Parisian prostitution when Napoleon the Third was on the throne.” Her “aristocratic fingers cling to the sceptre of mankind with a grip that tightens more than ever…”

Henriette de Barras (pictured in 1880) was “one of the daintiest little creatures in Paris, with a wasp-like waist that she contrives to make smaller still with tight lacing; a plump figure; small regular features and a most candid, innocent manner of speaking.”

Photographic portraits such as these allowed the demimondaines to show off expensive jewellery and opulent outfits and become trendsetters in matters of fashion.

Some of these women became top-class courtesans, occupying a tenuous position between high-class prostitute and mistress. Mainly from low-income families, les grandes cocottes became the lovers of wealthy financiers, politicians, and princes. A few, like Quéniaux, amassed vast personal fortunes.

3.5

| Female Spectacle:

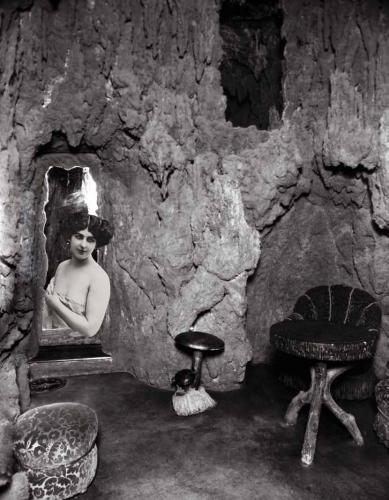

Photography, Theatre, and the French Courtesan

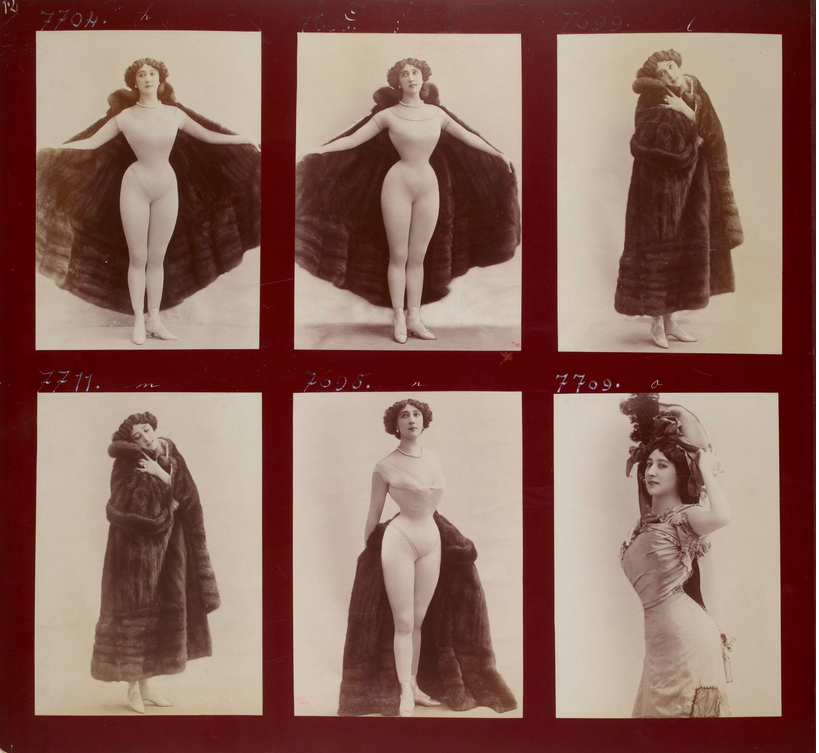

The birth of photography in 1839 heralded a new era in the depiction of the body and contributed to the rise of sexual consumerism. The daguerreotype process and the printing of images on albumen paper created highly defined photographs that perfectly reproduced skin’s texture and transparency and the nuances of gestures and facial expressions. These images were sold illicitly to male clients to stimulate sexual excitement.

In photographs that were discretely purchased by male buyers and in works of art produced by painters and exhibited at Salons, conventional codes of decency related to the nude female genre were subverted by sensual expressions, suggestive poses, and unconventional dress.

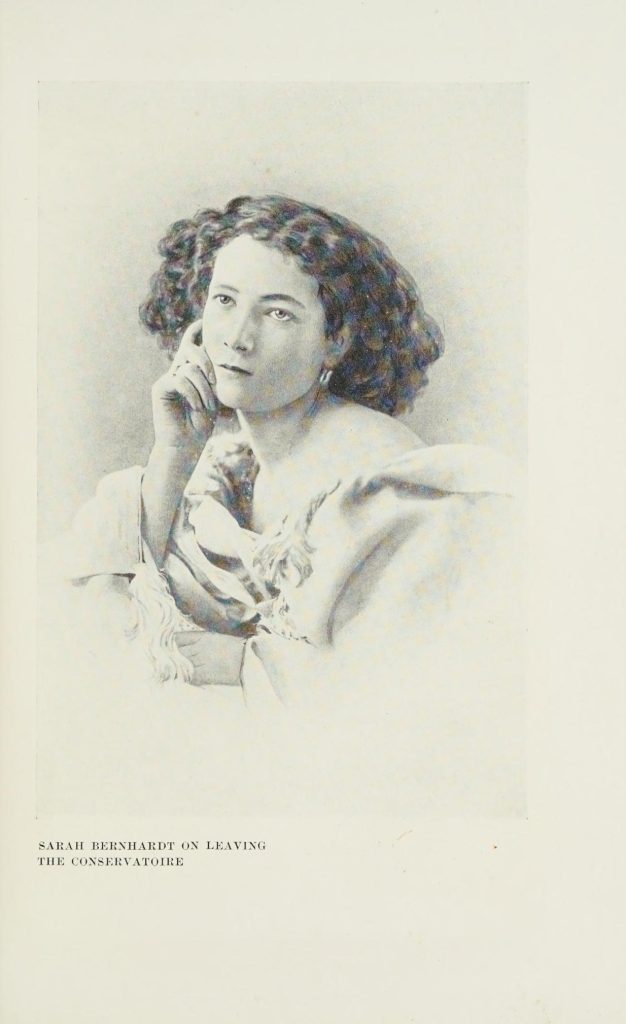

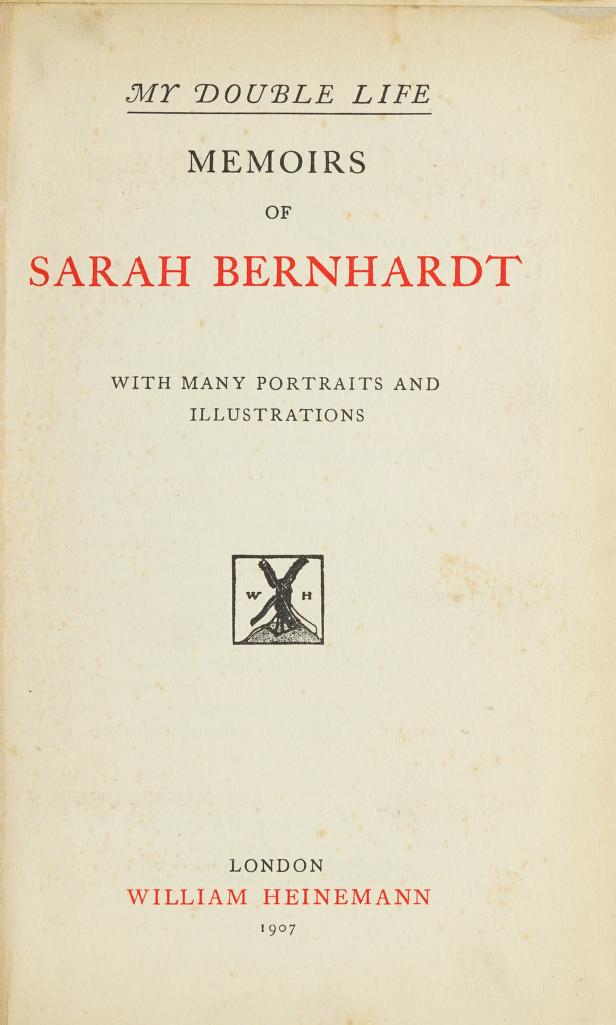

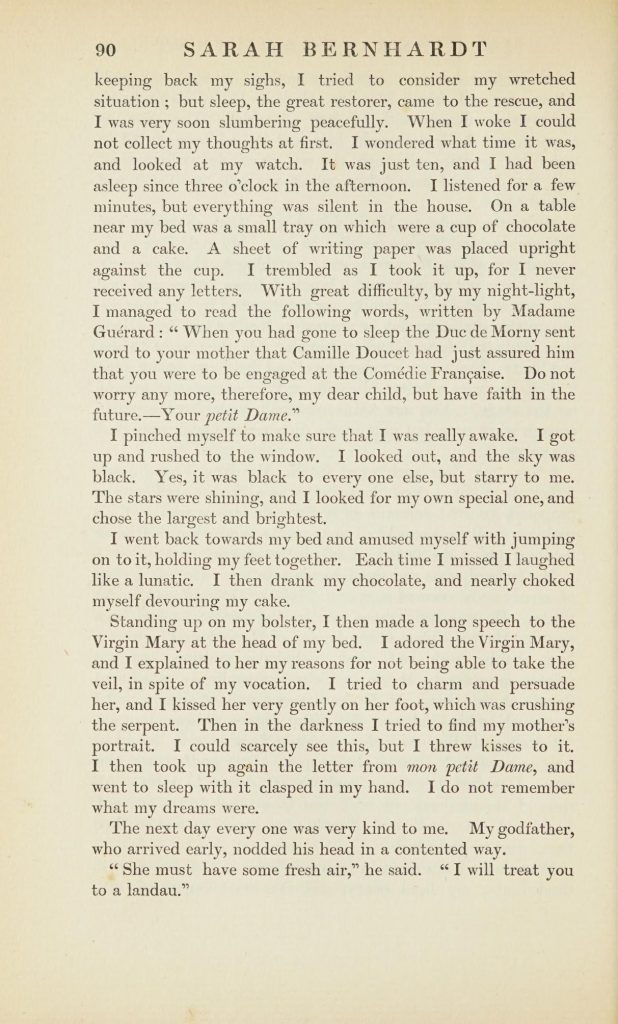

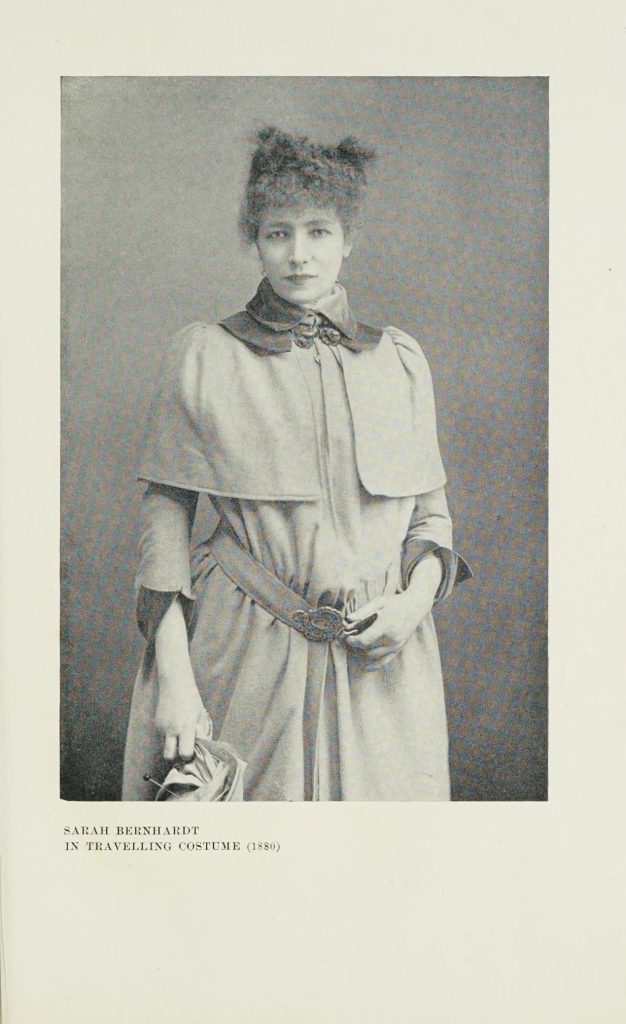

Whereas the female image had previously been defined by prescriptive sexual stereotyping, femininity could now be reimagined by women such as Sarah Bernhardt, whose role as an actress allowed her to flaunt traditional female dress and modes of behaviour. Bernhardt personally managed her self-image, collaborating with painters, sculptors, photographers and poster designers, who were charged with depicting her many personas.

Susan A. Glenn writes in Female Spectacle: The Theatrical Roots of Modern Feminism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000, 10): “Bernhardt symbolized the radical new possibilities that theatre presented for elaborating new forms of female identity.” Bernhardt was independent and strong-willed. She refused to conform to social norms. A feminist decades before that term became popular, she was a transitional figure who often played the binaries.

Georges Clairin’s portrait of Bernhardt was well received at the 1876 Salon exhibition. In his review of the exhibition, Théodore Véron stated: “The portrait of Madame Sarah Bernhardt is clearly one of the most fascinating works of the Salon for the originality of its composition and its splendid colors.” (Théodore Véron, Le salon de 1876: mémorial de l’art et des artistes de mon temps, 1876)

Bernhardt, at home in her Oriental apartment, looks seductively at the viewer, her alluringly curvaceous body emphasized by a long robe of shimmering white satin. She rests on a luxurious divan of pink satin (designed for use as a couch or bed) as she leans on a large cushion of gold satin. By her side, complementing her shapely form, is a yellow hound with long legs resting on a fur rug. A large Venetian mirror, purple velvet curtains and a tropical plan contribute to the exotica of the portrait.

Below is a brief review of Bernhardt’s professional life as an actress and artist; and her personal life as a courtesan.

Professional:

Sarah Bernhardt was the first international stage star. A versatile actress with an expressive voice and poetic gestures, she was lauded for performances as Phaedra in Racine’s Phaedra (1874), Victor Hugo’s Doña Maria in Ruy Blas (1872) and Doña Sol in Hernani (1877). Bernhardt founded the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt in 1899 and bought a series of French theatres in the 1880s and 90s, producing modern experimental plays while also touring Europe, the United States, Latin America, and Canada.

Bernhardt wrote, painted, and sculpted, exhibiting her work at the Paris Salon between 1874 and 1886. Exhibitions of the artist’s sculpture were also held in London, New York, and Philadelphia. Bernhardt participated in the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900. She excelled at sculptural modelling and shaping; most of her sculptures are portrait busts, though she also made smaller objets de vertu (objects of virtue). In addition, she painted, designed dresses, and supervised the sets and costumes for her productions.

Personal:

Sarah Bernhardt was born on October 23, 1844; her mother, Judith-Julie Bernhardt, was Jewish of Dutch origin. When Sarah was born, Judith was 23 years old and one of the beautiful young courtesans working in Paris. Sarah’s father was unknown, although it is likely that he was the Duke of Morny, a half-brother of Emperor Napoleon III. In 1853, at 9, she was admitted to the Colegio Grandchamp, where she was baptized, had her first communion, and performed her first theatrical performance. The mystical atmosphere of the school made her consider becoming a nun. After leaving Grandchamp at 15, her mother tried to introduce her to the courtesan world, but Sarah, influenced by her convent upbringing, flatly refused. Instead, through the influence of Morny, she enrolled in the Conservatoire de Musique et Déclamation, where she studied until 1862.

>After leaving the Conservatoire, she began her career with the prestigious Comédie-Française. In 1864, she met Charles-Joseph Lamoral, Prince de Ligne, one of her great loves, and became pregnant with her son Maurice but did not marry. For a brief time, she followed in her mother’s footsteps as a courtesan of the imperial court until she could financially support herself and her child as an actress.

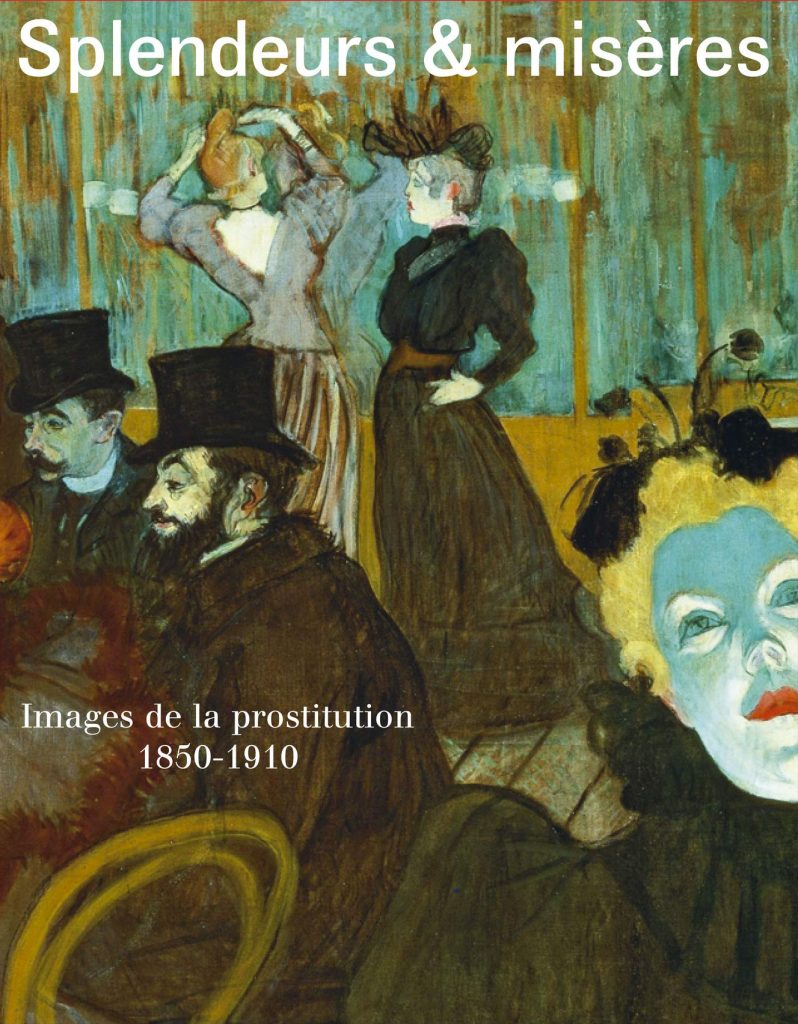

Bernhardt’s autobiography My Double Life: Memoirs of Sarah Bernhardt chronicles her strategic celebrity. First published sixteen years before her death, it begins with childhood reminiscences of her mother in 1844 and concludes with her tour of North America in 1880, while providing glimpses into her private life.

See these two examples of text and image:

In My Double Life, Bernhardt described wearing her sculptor’s outfit as follows:

My aunt Betsy had come from Holland, her native country, in order to spend a few days in Paris. She was staying with my mother. I invited her to lunch in my new unfinished habitation. Five of my painter friends were working, some in one room, some in another, and everywhere lofty scaffoldings were erected. In order to be able to climb the ladders more easily I was wearing my sculptor’s costume. My aunt, seeing me thus arrayed, was horribly shocked, and told me so. But I was preparing yet another surprise for her. She thought these young workers were ordinary house-painters, and considered I was too familiar with them…. When the song was finished I went into my bedroom and made myself into a belle dame for lunch. My aunt had followed me. “But, my dear,” said she, “you are mad to think I am going to eat with all these workmen. Certainly in all Paris there is no one but yourself who would do such a thing.” “No, no, Aunt; it is all right.”

And I dragged her off, when I was dressed, to the dining-room, which was the most habitable room of the house. Five young men solemnly bowed to my aunt, who did not recognise them at first, for they had changed their working clothes and looked like five nice young society swells… Suddenly in the middle of lunch my aunt cried out, “But these are the workmen!” The five young men rose and bowed low. Then my poor aunt understood her mistake and excused herself in every possible manner, so confused was she.

3.6

| The Brothel as Modern Subject

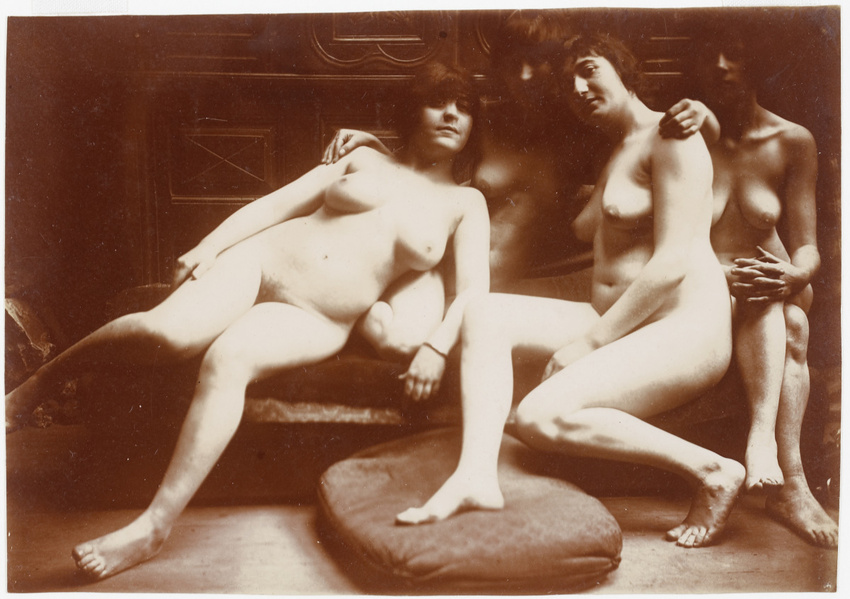

Brothels became a laboratory for artists looking for modern subjects and new approaches to render the female nude.

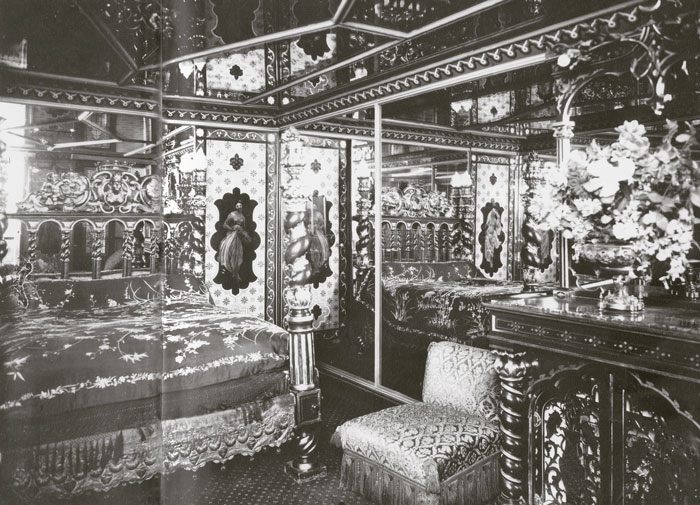

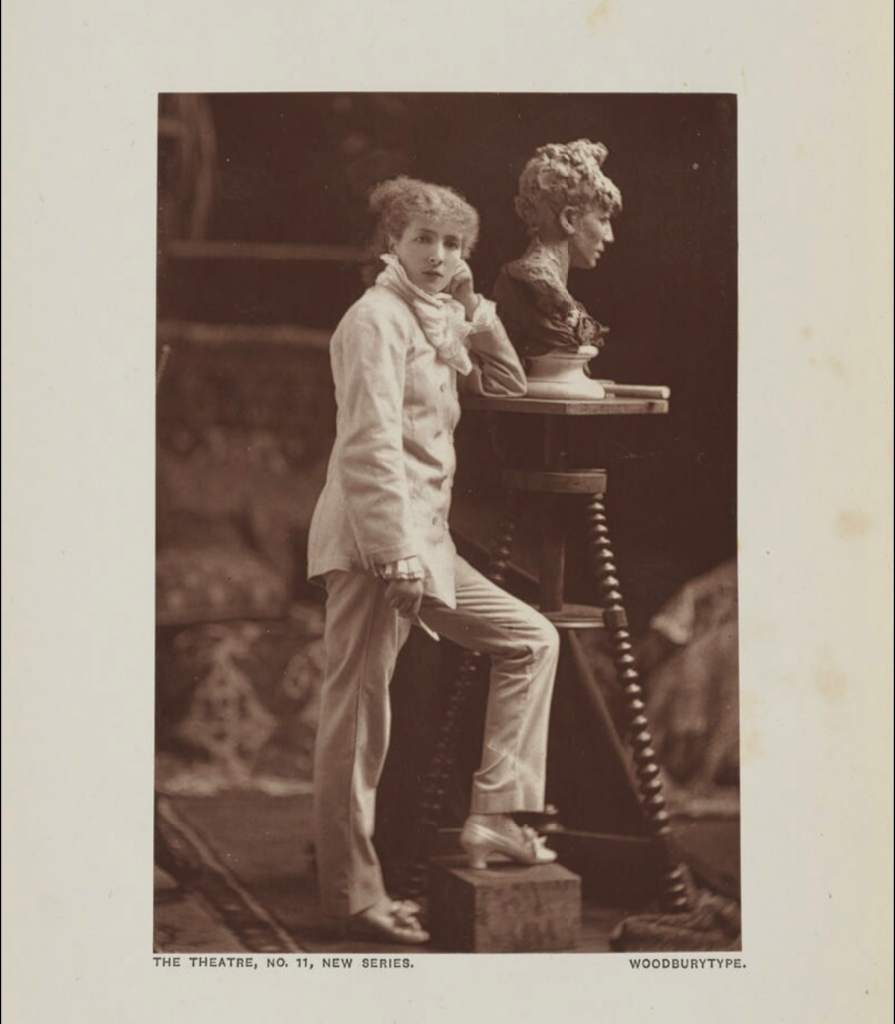

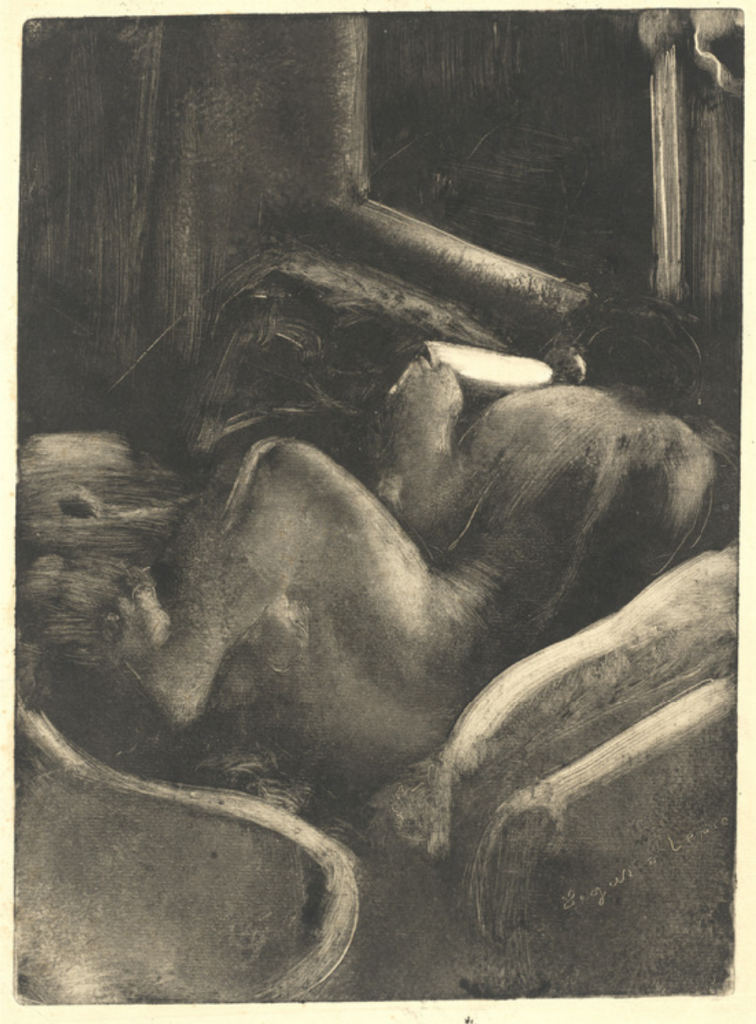

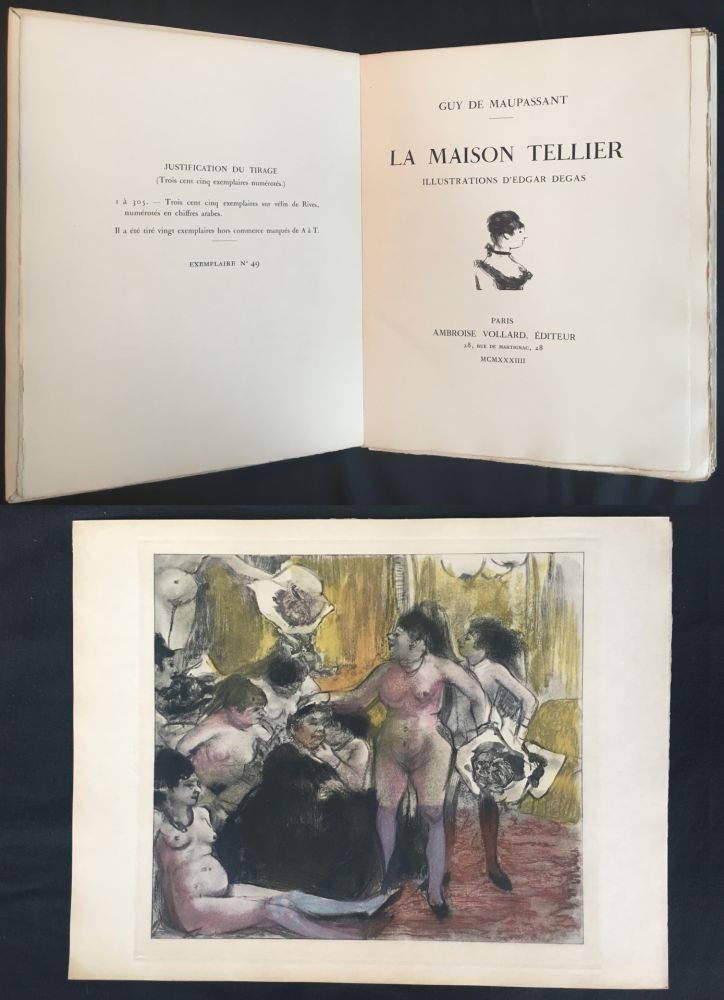

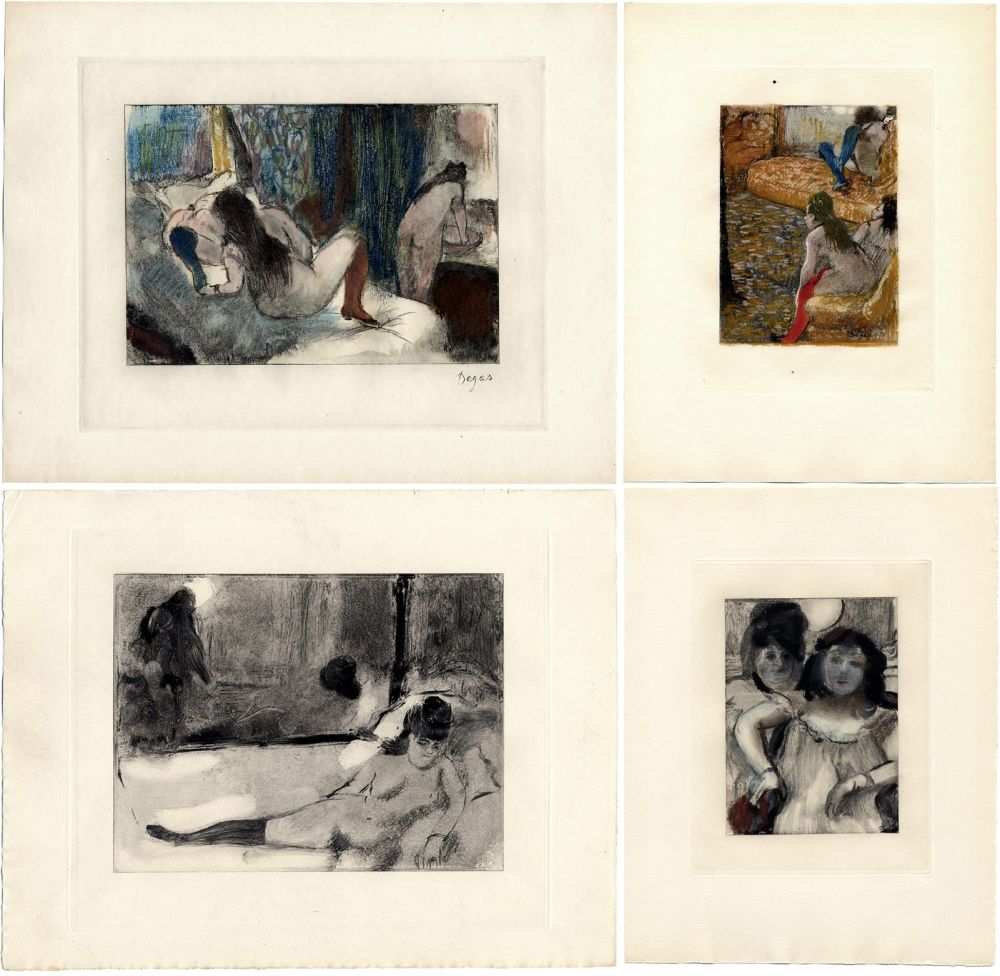

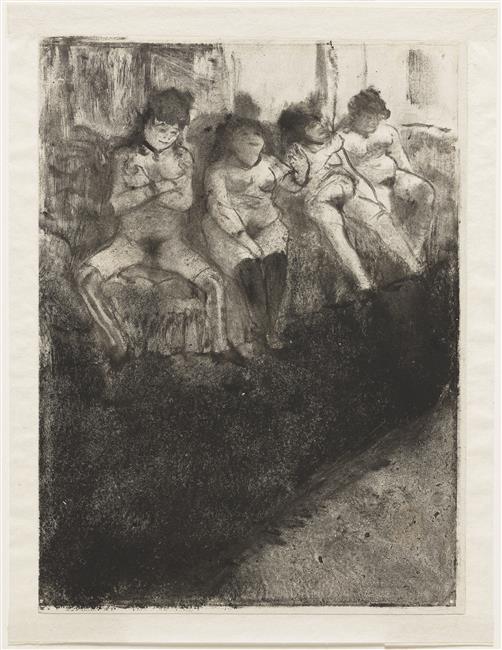

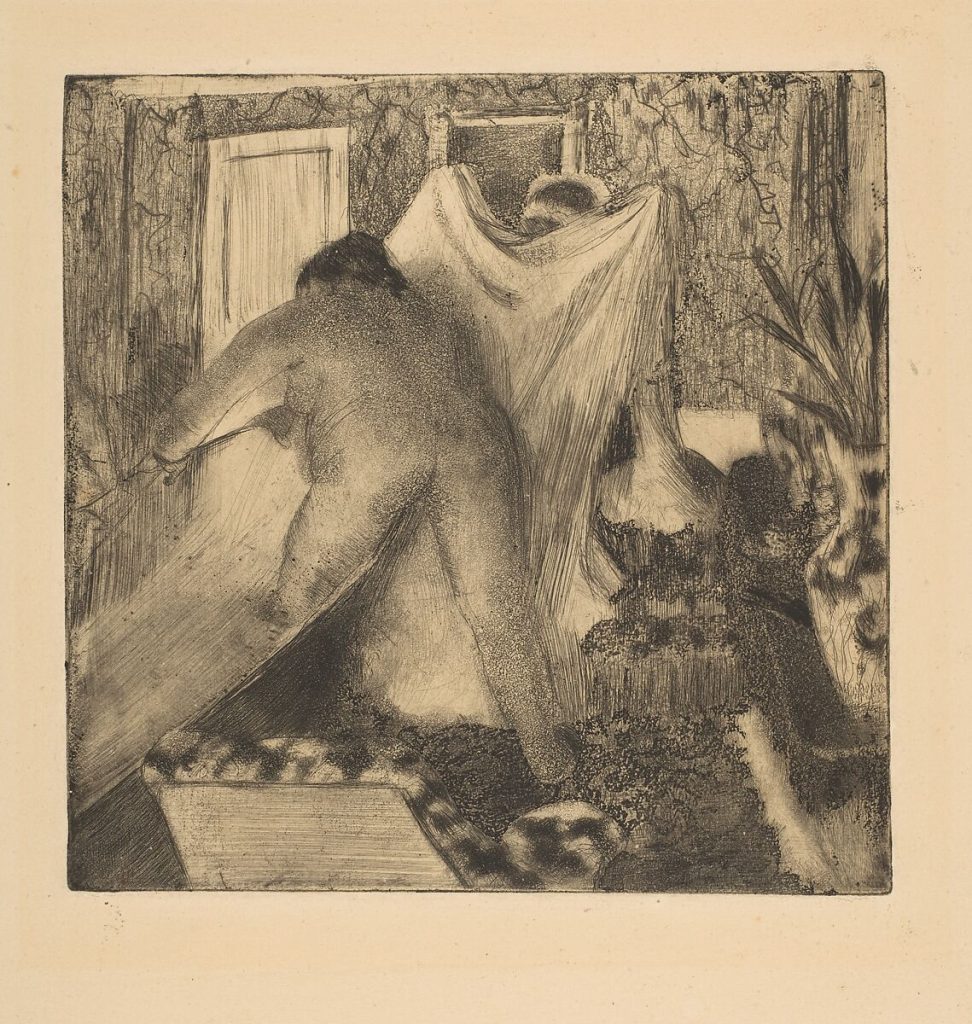

Edgar Degas produced more than fifty small monotype prints of brothel interiors in the late 1870s. These deluxe brothels were decorated with stuffed sofas and chairs, chandeliers, and mirrors in carved frames.The artist’s aims were twofold: to create formally experimental and innovative prints and to record a provocative contemporary practice. His images are direct, daringly shorthand, and dispassionate.

The Client candidly illustrates the selection process that occurs at a brothel. Clayson (Painted Love, 39) describes the customer as a “fragmentary” figure:

He wears a hat and he smokes, underscoring his already considerable physical distance from and social disregard for the pair of naked prostitutes. The thickset woman at the center, shoulders stiff and arms pulled into her side, looks done up like a package of flesh, ready to be taken. As usual, Degas varies the scene by contrasting the positions and actions of adjacent figures. The near woman rests a bent arm jauntily on her upper thigh and flexes her legs; the tilt of her head and the set of her mouth appear conversational, yet there is not a trace of coquetry. The two women carry out this stage of their unrelentingly physical work without recourse to elegant maneuvers or to any of the bodily conventions of romantic intimacy.

In the Salon is a more complex composition of nine prostitutes, sprawled all over the room, and the mistress of the house. The male client is edged to the side, half visible and top-hatted. He and the madame compositionally bracket the half-dressed female workers. They stand stiffly, fully dressed, in contrast to the seeming state of abandon of the filles. Clayson:

In spite of the transgressiveness of the way their bodies are figured, the women of the monotypes do not appear rude in their disregard of the etiquette of intimacy — both prostitutional and bourgeois, venal and romantic — or particularly bad-mannered in their occasional self-absorption. The point is that their childlike, bete, good-natured otherness does not conflict with the obligations and circumstances of their work as Degas has defined it in the monotypes. Their particular, tenacious physicality seems intended to embed them in a world of the sheerly material, where the subjective self has been suspended, cancelled, or long since overridden. Degas’s prostitutes lead an existence in which the self and the body have become the same and the women’s sexuality has been lost to the world of exchange. (Clayson, Painted Love, 59)

Degas’s brothel prints have been interpreted variously over time. Charles Bernheimer investigates his medium and technique in “Degas’s Brothels: Voyeurism and Ideology” (Representations 20 (Autumn 1987): 158-186). Bernheimer argues that Degas’s brothel monotypes “destabilize the male viewer’s gaze and confront him with the ideological assumptions underlying his voyeuristic position.” He disagrees with writers who suggest Degas’s voyeurism was misogynist because of his humiliation of the women he observes. The images are not destabilizing because they objectify women but because they speak of a capitalist ideology that defines and confines a woman’s value. “Degas exposes the material effects of this repression. As against the misogynist identification of woman with her inherent mutilation, the horror that must be disregarded, he sets a sympathetic identification of woman with her social and historical commodification.”

Bernheimer recognizes that in Degas’s monotypes, “the medium is most certainly a good part of message …” A technique with both painterly and drawing qualities, the monotype can be created by markings on a plate covered with thick, greasy printer’s ink which is then wiped off (the so-called “dark-field” manner) or through the direct application of printer’s ink on a clean plate (the “light-field” manner). Once the design is completed, it is transferred to dampened paper and run through a rolling press. It is an imprecise process with unpredictable outcomes, but its physical immediacy and sensuous tactility rendered it attractive to Degas.

He achieved his desired effects using rags, brushes, stiff bristles, sponges, pins, and direct applications. The prints are smudged, his forms scribbly, giving the impression of a rapid sketch. The laying out of broad tonal areas without reliance on lines, the basis of dark field monotypes, allowed Degas to explore the formal problems of a black-and-white composition. The act of wiping ink from the plate was a process that enabled him to experiment with imagery without using a pencil or paintbrush. In these prints, Degas’s aesthetic practice differed from the other Impressionists who expressed the effects of light in the language of colour.

It is interesting to note that Degas’s monotypes were never exhibited during his lifetime. While he may have shown them privately, there are no accounts of them being on public display until 1934, when the art dealer Ambroise Vollard reproduced a selection in his 1934 edition of Guy de Maupassant’s La Maison Tellier and his 1935 edition of Mimes de courtisanes by Pierre Louys.

The women in these scenes display themselves without artifice or pretence but as they are, slouching, slumped bodies, their faces marked by expressions of weariness, fatigue or boredom.

Clayson argues that Degas constructed female bodies that broke with the canons of decorous nudity institutionalized by Salon paintings. This departure from convention involved rendering a different type of nakedness: bloated bodies, sagging breasts and tired faces, which contrasted drastically with the smooth perfection and flawlessness of academic figures. Beyond appearances, it was also a matter of connotation. Degas’ monotypes portrayed a female physicality that rejected the erotic codification of the Salon nude and showed the stark reality of an unrefined sexual market instead. The coarse faces of the sex workers were stereotypical, in many cases simian-like or bearing similarity to the physiognomic facial codes assigned to criminals.

3.7

| Deviance, Racism and the Other

Through the 1870s and 1880s, the prostitute was increasingly seen as a deviant figure, a catalyst for society’s fears and obsessions.

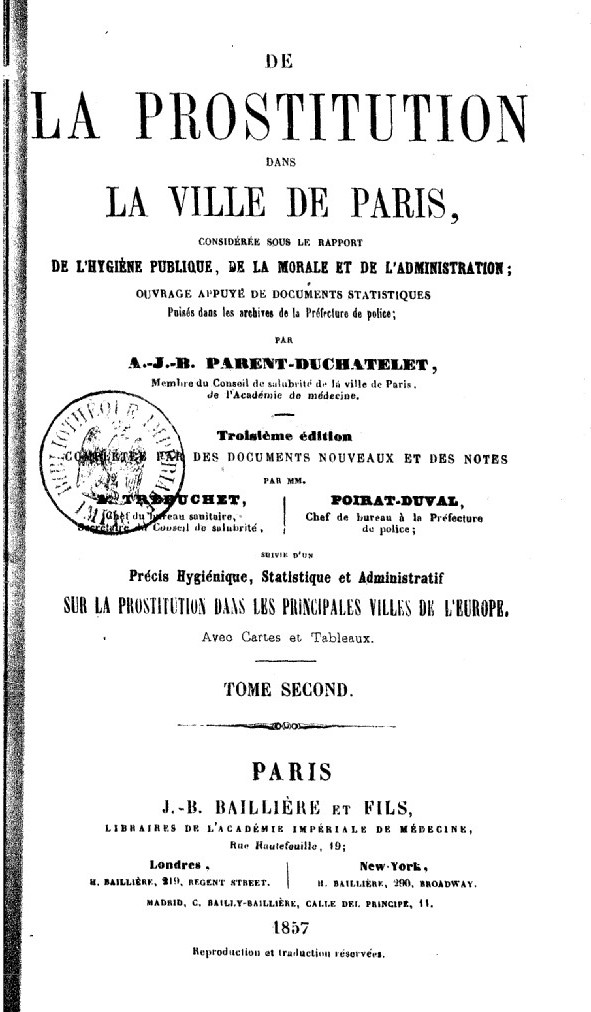

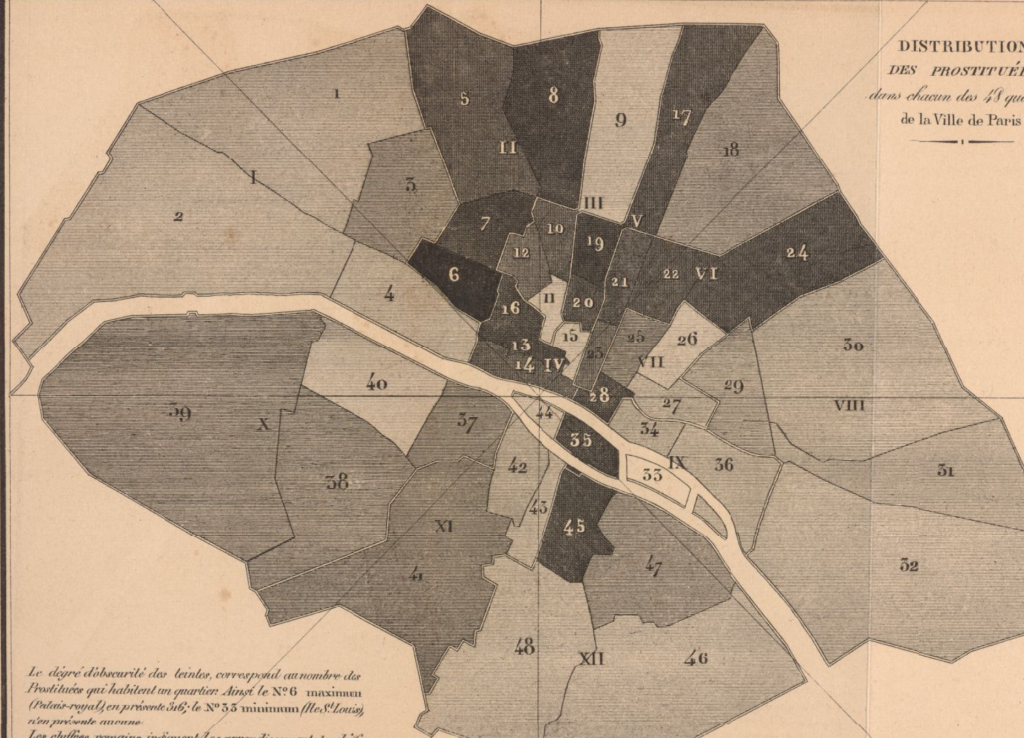

In the 1830s, Alexandre Jean-Baptiste Parent-Duchâtelet a French physician and one of the most eminent hygienists of the nineteenth century who had been working on decomposing corpses, directed his attention to prostitution, which he saw as another site of biological decomposition and morbid decay. Parent-Duchâtelet attempted a comprehensive classification of registered prostitutes in Paris to explain their deviant characteristics. His findings determined that prostitutes were immature, unstable, disorderly, plump, crude in language and behaviour, and sensually excessive, leading him to conclude that they were highly susceptible to lesbianism.

Lesbianism was immoral, frequently reiterated as such in the records of physicians like Parent-Duchâtelet, and in police investigations, as well as in the literary works of Balzac, Zola, Maupassant and Baudelaire, where lesbianism symbolized evil, moral or social decay, and was a harbinger of pain and death.

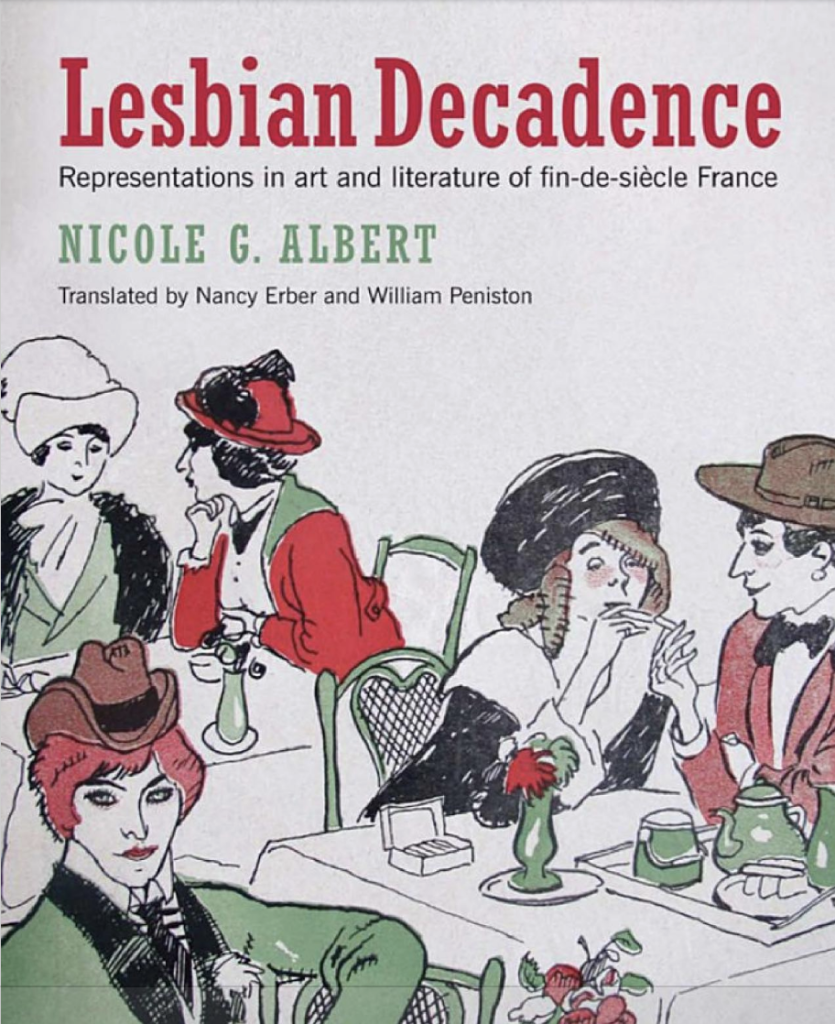

Nicole G. Albert in Lesbian Decadence explains that it was Napoleon’s implementation of civil and criminal codes that prevented lesbianism and consensual same-sex activity from being defined as criminal behaviour in France. Still, lesbians, who were not visible in art and literature until the late nineteenth century, were considered a sign of social malaise and moral vice.

Baudelaire’s volume of French poetry Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil, first published in 1857) contained six poems with lesbian content. Deemed immoral, the French court censored the poems which remained unpublished until 1949. Still, in the second half of the nineteenth-century straight French men wrote about lesbians and depicted them in art, often to titillate other straight French men. At the same time, doctors and pioneering psychologists who read Alexandre Parent du Châtelet’s De la Prostitution dans la ville de Paris and publications from elsewhere began the task of categorizing lesbians more precisely and even medicalizing them in an attempt to “cure” them.

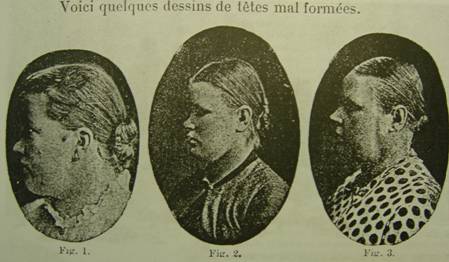

In 1889, Pauline Tarnowsky, a female Russian physician expanded upon this common viewpoint in Étude anthropométrique sur les prostituées et les voleuses (Anthropological Study of Prostitutes and Female Thieves). This was a significant work of nineteenth-century anthropology, pathology and public health, which became central to discussions on the nature of the prostitute. Tarnowsky analyzed the physiognomy of the Russian prostitutes under observation, including their excessive weight, skull size, hair, ears and eyes, as well as their family background and signs of degeneracy. The finding of facial abnormalities, including asymmetries of the face and nose, overdevelopment of the parietal region of the skull, and the so-called Darwin’s ear, were seen as indicators of the primitivism of a prostitute’s physiognomy, flaws that only a scientist could see. Their “strong jaws and cheek-bones and their masculine aspect…hidden by adipose tissue emerge, salient angles stand out, and the faces grow virile, uglier than a man’s.” For Tarnowsky and others, the appearance of the prostitute and her sexual identity were preestablished in her heredity, with physiognomy and genitalia changing over time, the latter becoming more diseased as the prostitute aged.

In contrast, Courbet’s The Sleepers does not connote this negative stereotype. First acquired by a relative of Napoleon, the painting was found to be “unsuitable”(“peu convenable”) by the man’s wife and returned, only to be purchased for a second time by Khalil Bey, the Turkish collector who had commissioned Courbet’s The Origin of the World.

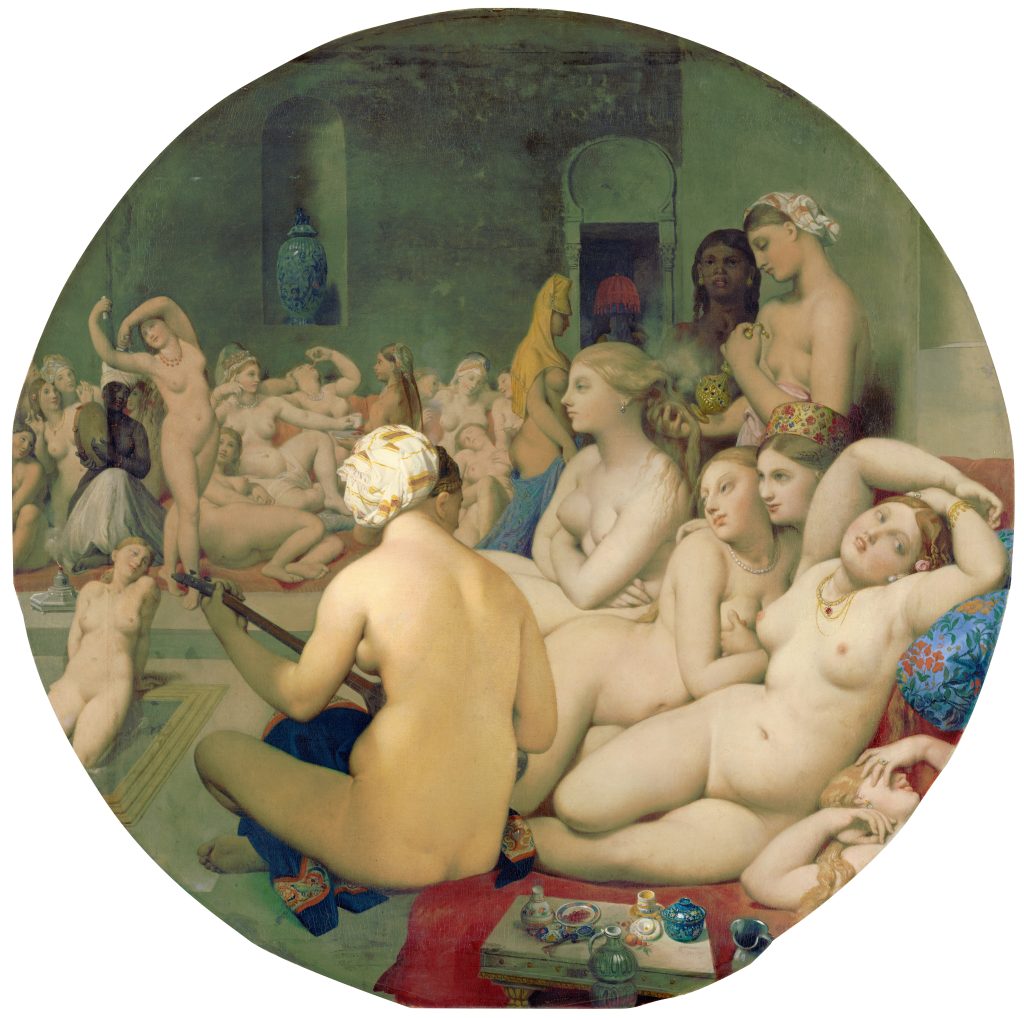

The work has been described as Courbet’s personal fantasy, a product of male imagination. The subject’s appeal was partly the absence of male figures whose presence would curb a lesbian reading and the enjoyment of the (male) observer/viewer/voyeur. Male voyeurism, the practice of gaining sexual pleasure from watching others when they are naked or engaged in sexual activity, was stimulated as well by the Orientalist harem subjects of Jean-Léon Gérôme,

and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, to name a few, which were popular throughout the nineteenth century.

In Ingres’s Turkish Bath, the effect of a “keyhole” view may have influenced his decision to cut his square canvas into a circle, allowing the voyeur the illusion of a more discrete violation of privacy. Anna Secor writes in “Orientalism, Gender and Class in Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s Turkish Embassy Letters: to persons of distinction, men of letters and c’” (Cultural Geographies (formerly Ecumene) 6, no. 4 (1999): 375-398):

From the feminization and sexualization of the Orient in Western accounts arose a fascination with the sexual female spaces of the women’s baths and the harem. In the Western imagination, it became the Oriental woman herself sensual, muted and subjugated – who apotheosized all that was understood to be Oriental. George Sandys, who began his travels in the Ottoman empire in 1610 and whose work Montagu cites in her letters, viewed the hammams, or public baths, as the site of homoeroticism between women: “Much unnatural and filthy lust is said to be committed daily in the remote closets of these darksome Bannias,” he writes, “yea, women with women; a thing incredible, if former times had not given thereunto both detection and punishment.” Similarly, Baudier wrote that lesbianism was so widespread that “whenever a Turk wishes to marry a Turkish woman, he begins by finding out whether she is in the thrall of some other women.”

The published letters that Lady Mary Wortley Montagu wrote in 1717, when she accompanied her husband on his ambassadorial mission to the Ottoman court, negated the idea that this feminine space was in any way improper. Lady Montagu emphasized “the modesty and good breeding of the women she encounters there, portraying the bath as a communal space where the markings of rank are stripped off and where women are able to consort.”

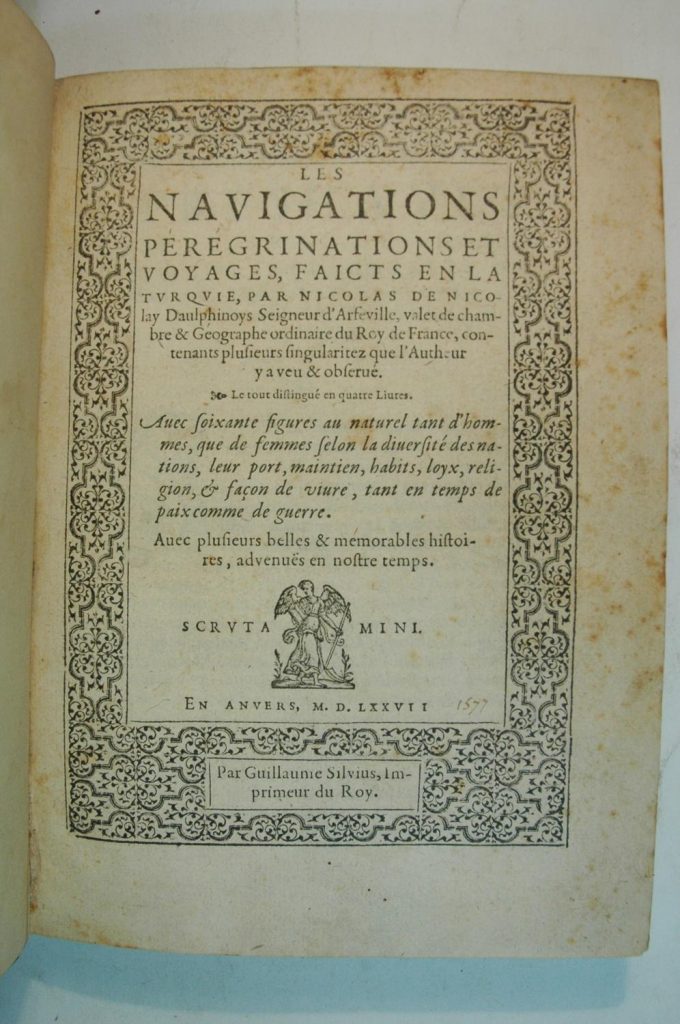

Ingres had read Lady Montagu’s letters. The atmosphere of The Turkish Bath, however, bears little resemblance to her record. Instead, he based the image on his reading of Les navigations, peregrinations et voyages, faicts en la Turquie by the sixteenth-century French traveller Nicolas de Nicolay. This text associated the women’s baths with homoerotic pleasure:

Amongst the women of Levant, there is very amity proceeding only through the frequentation & resort to the bathes: yea & sometimes become so fervently in love the one of the other as if were with men, in such sort that perceiving some maiden or woman of excellent beauty they will not cease until they have found means to bath with them, & to handle & grope them everywhere at their pleasure, so full they are of luxuriousness and feminine wantonness: Even as in times past were the Tribades, of the number whereof was Sapho the Lesbian. (Nicolay 1585: 60; see Efterpi Mitsi, “The Turkish Bath in Women’s Travel Writing Private Rituals and Public Selves,” in Gómez Reus, Teresa and Aránzazu Usandizaga, eds., Inside Out: Women Negotiating, Subverting, Appropriating Public and Private Space. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2008, 47-63).

Ingres felt comfortable representing the Orient as a deviant paradise full of naked or semi-naked female bodies because harem scenes and the presence of lesbian love could successfully conjure the erotic ideal of forbidden pleasure. This connection between lesbianism and an imagined Orient, what Ruth Bernard Yeazell called Harems of the Mind (Yale University Press, 2013) persisted throughout the nineteenth century.

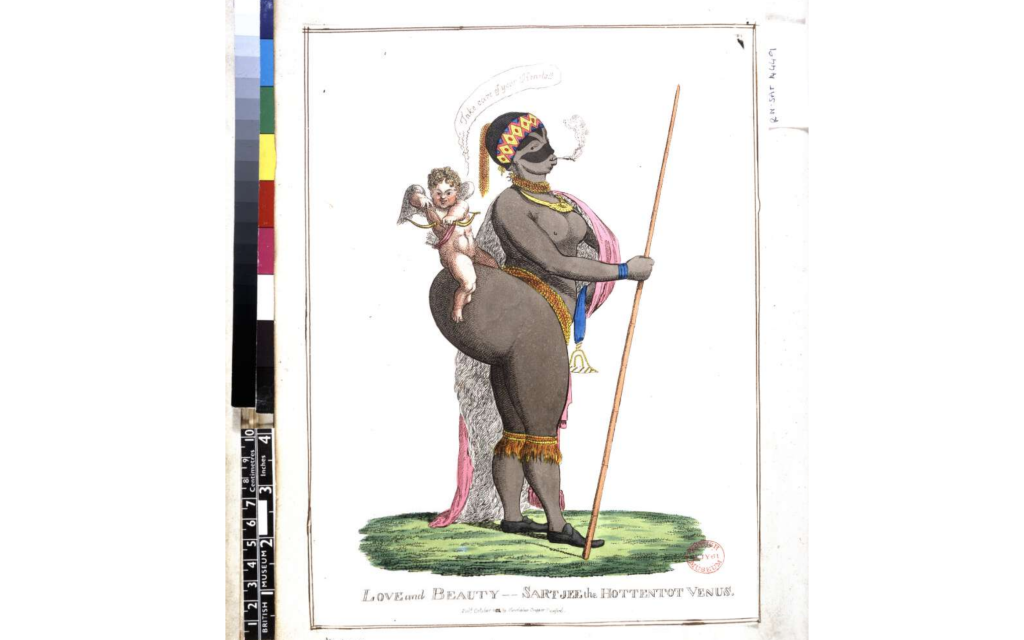

For Degas, lesbianism was the outward manifestation of deviance and primitivism. Two Women (Scene from a Brothel) makes this allusion through the emphasis on curves and buttocks, reflecting the pictorial conceptualizations of deviance in France at the time. The protruding buttock of the black woman seen here is visually echoed by a murky blackness that envelops her body, creating an association with what was deemed primitive, subhuman and hypersexual.

An interest in the physiognomy of the black female, from skin colour to body shape, first surfaced in London in 1810 through the vulgar public parading of a woman called Saartje (Sarah) Baartman, a South African from a southwestern region of Africa. She was displayed to European audiences to show the anomaly of her buttocks: her steatopygia, a characteristic of protruding buttocks, that early travellers to Africa had discovered. To the audiences who came to see her, she was no more or less than a collection of sexual parts.

In France, her body was analyzed by so-called scientists for sub-human, animalistic traits. Her buttocks and genitalia were thought to be evidence of her sexual and intellectual primitivism, comparable to an orangutan. Destitute and penniless, Sarah turned to prostitution in Paris and died in 1815 at the age of twenty-six.

3.8

| Degas’s Bathers

In the 1870s, when nudes depicted as bathers first appeared in Degas’s monotypes, the images were uncompromisingly descriptive, the figures clambering in and out of carefully detailed bathtubs, dressing or undressing in gaudy bedrooms, or vying for the attention of top-hatted men. The figures were often physically exaggerated, comical, mundane, or grotesque.

As an image, bathing was connected to the cleansing rituals of prostitutes and therefore to prostitution. Even though bathing was not a common occurrence in mid-nineteenth century France (French scientists and doctors did not advise taking more than monthly baths), prostitutes were required to do so. Therefore, images of bathtubs were not regarded as a reflection of everyday life, but were emblematic of the lived experience of prostitutes.

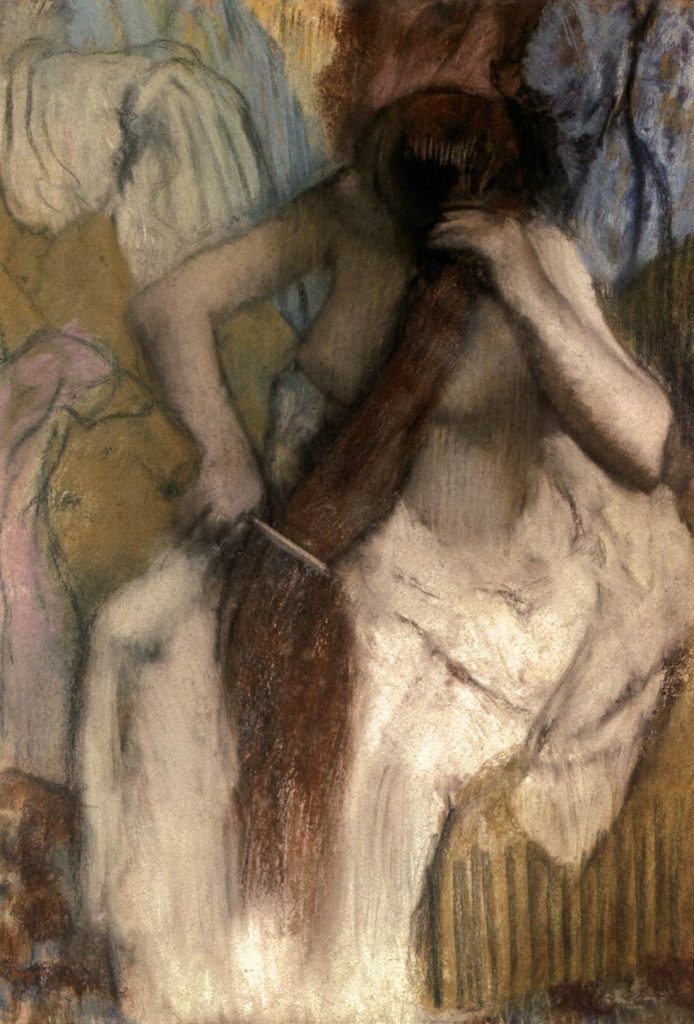

Degas’ pastels of women’s bathing rituals became more fluid and less graphic over time. Increasingly, the women were portrayed as self-absorbed, and an interiority permeated the images that impacted the viewing experience.

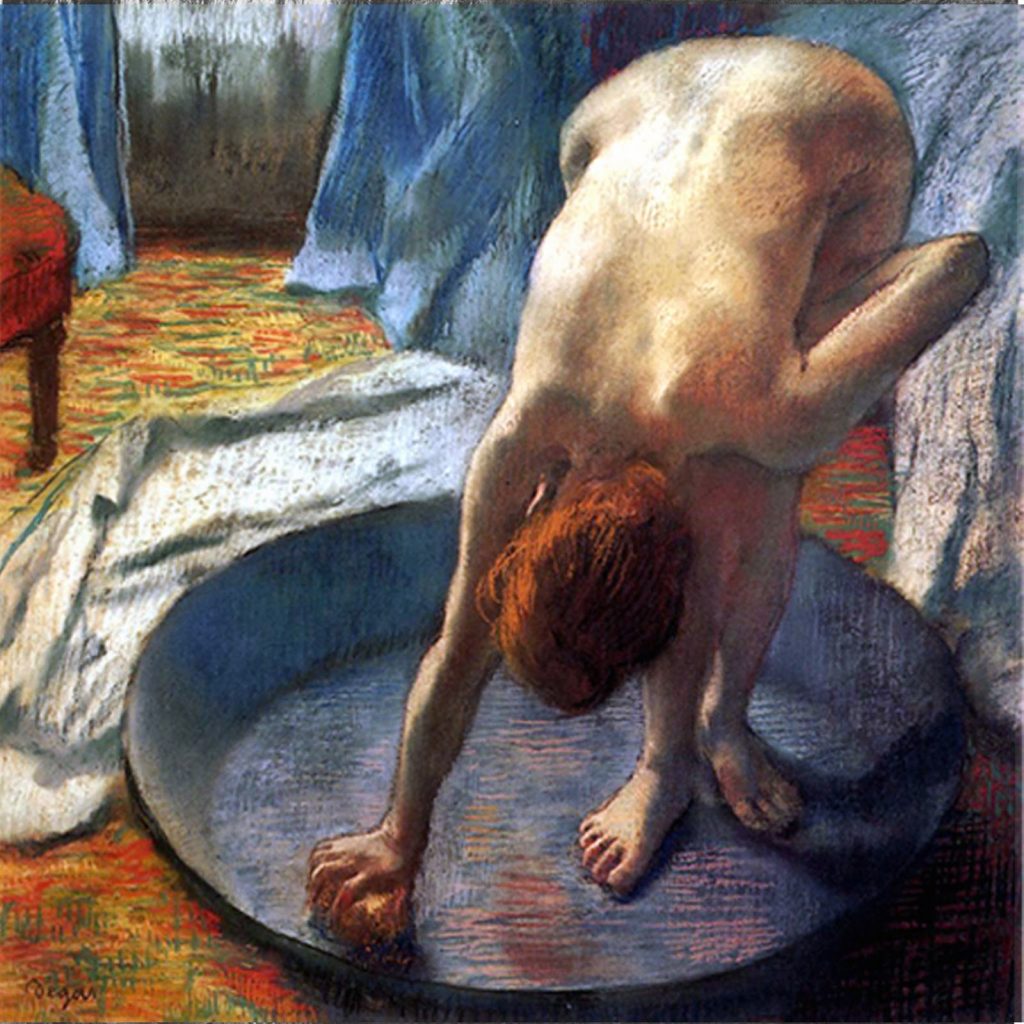

Women in a Tub exemplifies this shift in pictorial nuance. It forms part of a series of pastels of women at their toilette from the mid-1880s, works that were included in the eighth and last exhibition of Impressionist works held in Paris in 1886. While art historians have written admiringly about these images, art critics at the time were offended by the models’ relaxed, ungainly and unattractive nakedness.

Charles-Marie-Georges Huysmans, novelist and art critic, wrote scathingly that “Degas brought to his study of nudes a careful cruelty, a patient hate…He must have wished to take revenge to hurl the most flagrant insult at his century by demolishing its most constantly shrined idol, woman whom he debases by showing her in her tub in the humiliating positions of her intimate ablutions…He gives to her a special accent of scorn and hate.”

Another art critic Félix Fénéon agreed, stating “…crouching gourd-like women fill the bathtubs…One with her chin on her breast is scratching the nape of her neck; another, her arm struck to her back and twisted a half circle is rubbing her behind with a dripping sponge…Hair falling down over her shoulders, breasts over her hips, belly over her thighs, limbs over their joints, all of this makes this ugly woman-seen from above lying on her bed with her hands pressed to her hams-look like a series of rather swollen cylinders joined together.”

The aggressive tone taken to criticize the intimate subject matter is not surprising. Terminology such as “ugly,” “hateful,” “humiliating,” and “cruel” shows how shocking the imagery would have been. The critics may have also reacted to the changing iconography of women’s sexuality and class. A consequence of modernity was the confounding of stereotypical identities and the muddled application and reading, of codes of conduct.

Another of Degas’ suite of pastels, Woman Bathing in a Shallow Tub, makes no allusions to brothels, customers, or the symbolic paraphernalia of prostitutes’ dress, stockings, ribbons and so forth. The viewer is left to invent a narrative. Without contextual props, the figures could be ordinary women, wives, or mothers, not clandestine subjects.

There is a sense of enclosure in Degas’s images which is heightened here by the tilting of the floor towards the picture plane and the figure’s centred body which looms large in the composition. The female is focused completely on the activity of bathing, just as all of Degas’s late nudes are absorbed in rituals of self-grooming — brushing or combing their hair, stepping in or out of a tub, or stretching their limbs as they reach for a sponge or towel. The absence of eye contact reinforces the discreet nature of the scene. They are believable in their normal movement, which is eloquently captured by Degas’s energetic application of pastels.

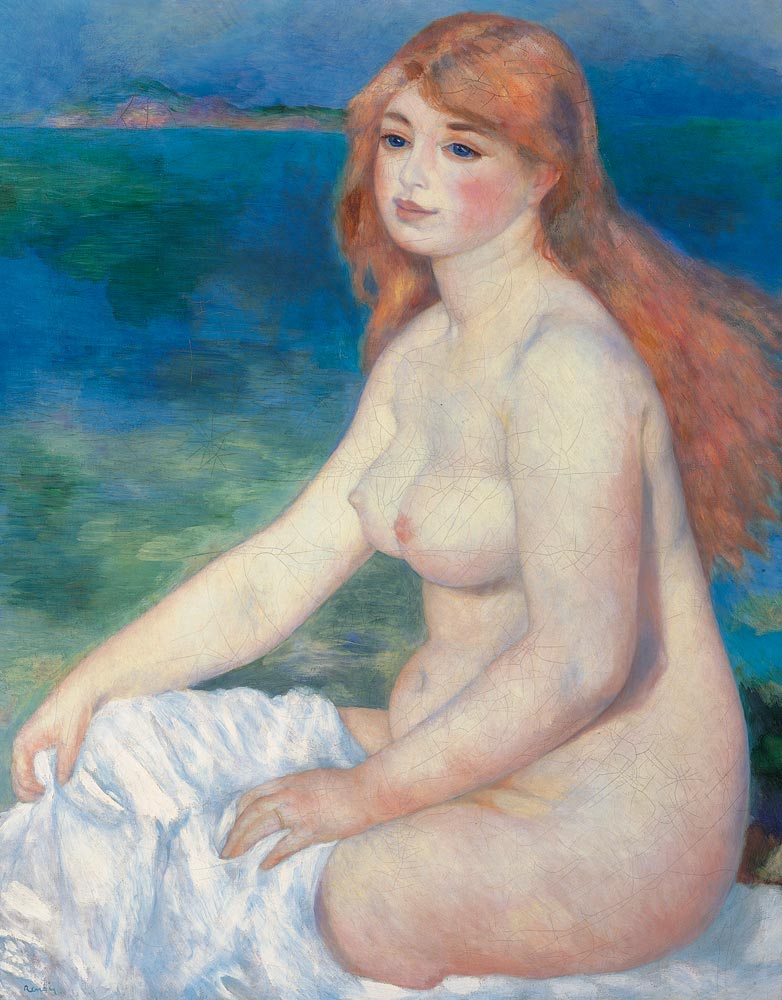

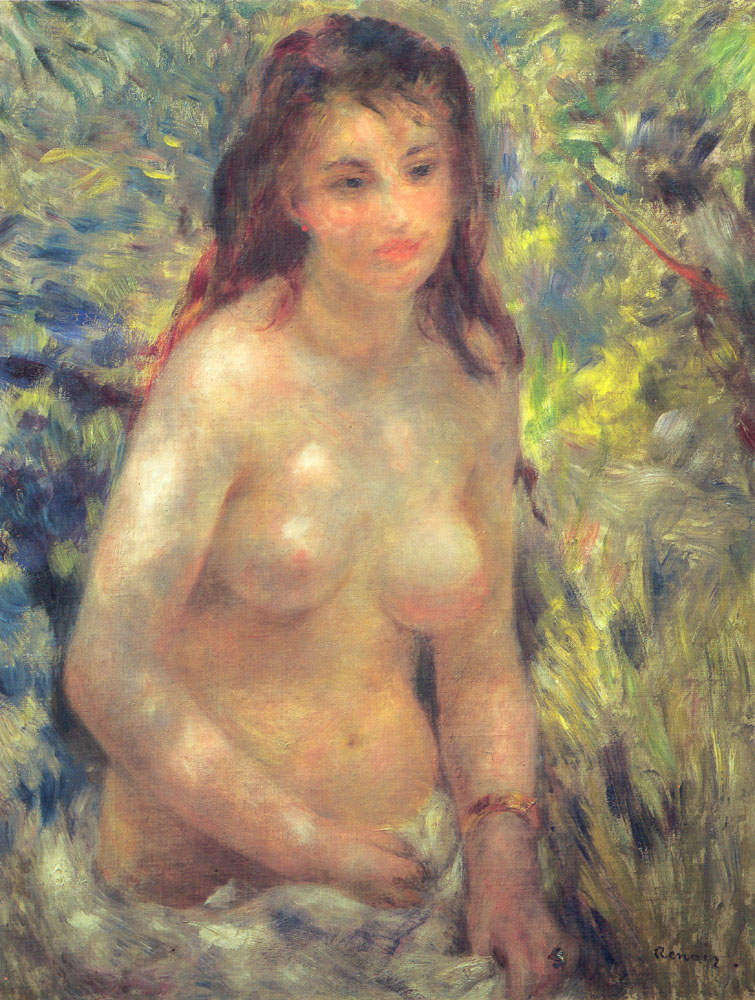

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s paintings of nudes stand in stark contrast to the interiority of Degas’s images. By the mid-1880s, Renoir had ceased to depict images of everyday life, preferring to paint monumental and idealized female forms, of which Blonde Bather is an example. The painting was created during Renoir’s trip to Italy in 1881. The model is believed to have been Aline Charigot, whom he later married. Aline had begun to pose for Renoir in 1880 and had accompanied him on part of this Italian trip.

John House writes about Blonde Bather in Nineteenth-century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine (Clark Art Institute, 2012, 672):

The form that the figure assumed was a direct result of Renoir’s artistic experiences on his Italian trip. In conversation with Jacques-Émile Blanche, Renoir pinpointed Raphael’s frescoes in the Villa Farnesina in Rome as the paintings that had the most significant impact on him: “Raphael broke with the schools of his time, dedicated himself to the antique, to grandeur and eternal beauty.” He wrote from Naples in November 1881 about the “simplicity and grandeur” that he found in Raphael’s frescoes and enlarged on this in a letter to Madame Charpentier early in 1882, shortly after his return to France, explaining what he had learned from Raphael: “Raphael who did not work out of doors had still studied sunlight, for his frescoes are full of it. So, by studying out of doors I have ended up by seeing only the broad harmonies without any longer preoccupying myself with the small details that dim the sunlight rather than illuminating it.” In addition, he expressed his admiration for the “simplicity” that he found in the wall paintings from Pompeii and Herculaneum that he saw in the Naples Archaeological Museum.

Renoir’s depictions of nude female subjects, such as Study Torso Sunlight Effect, resemble the popularized 19th-century genre that cast women as extensions of the natural world, meant to behold, caress, and consume. The naked female body was not just a metaphoric incarnation of Beauty, Truth, and Purity, but an element of nature, the rendering of her flesh in paint expressing an organic will to form.

Degas’s bathers, in contrast to Renoir’s nudes, crouch and hide themselves, their breasts and thighs hidden in shadows, their backs towards the viewer. His images are uncompromising in their focus on challenging poses. His facility with portraying such poses was the result of dedicated studies, a process of repeated observation which allowed the final product to retain the look of “naive and spontaneous movement.” Despite Degas’s transgression of visual codes, his representations are truthful renditions of the natural world, “even suffering and ridicule were an antidote to the unbearable confections of salon nudes.” (Heather Dawkins, The Nude in French Art and Culture, 1870-1910. London: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Kathryn Brown, in the Introduction of Perspectives on Degas (Ashgate, 2016), examines some of the key critical literature that has contributed to diverse re-interpretations of Degas’s brothel and bather images:

The charge of voyeurism that attached to Degas’s bather images assumed a prominent place in critical literature about the artist until well into the twentieth century. In 1889 Huysmans famously discussed the ‘attentive cruelty’, ‘spite’, and ‘patient hatred’ that, in his view, characterized Degas’s supposedly ‘truthful’ renderings of female intimacy. For Daniel Halévy, the depictions of nudes found in Degas’s studio after his death (‘cette oeuvre cachée’) amounted to a ‘defamation’ of the female body that –although devoid of misogyny – awakened simultaneous horror and admiration in the viewer. Even attempts by Rivière and Ambroise Vollard to ‘defend’ Degas against a charge of disliking women pitted examples of the artist’s courtesy in social relationships against allegations of pictorial ‘cruelty’ towards his female subjects, thereby mixing the personal and the fictional.

In a ground-breaking article published in the Art Bulletin in 1977, Norma Broude challenged the absorption of such views into twentieth-century scholarly interpretations of Degas. She proposed a rereading of his works that dispensed with a ‘preconception of misogynistic motivation’, pointing out the circularity of the evidence for this charge and showing how such an approach biased interpretations of the pictorial content of the works themselves.

From the 1970s onwards, the critical re-evaluation of Degas’s female nudes and brothel images continued to gain impetus. In her elaboration of female agency in Degas’s bather and brothel images, Eunice Lipton focused on the idea that many of these works depict women experiencing ‘intense physical pleasure’; she interpreted the charge of misogyny as a ‘displacement onto Degas of his male audience’s rage towards the depicted women and – by extension – towards changing contemporary definitions of women, sexuality, and class.’

While Carol Armstrong identified intricate structural features of the bather scenes that trouble the very possibility of a prurient gaze, contributors to the essay collection edited by Richard Kendall and Griselda Pollock (Dealing With Degas: Representations of Women and the Politics of Vision, Universe,1992) investigated multiple approaches to Degas’s portrayal of women. These included ways in which his works addressed broader social issues ranging from nineteenth-century scientific discourses, social power structures, and models of the family to the reinterpretation of such topoi from the perspective of feminist art history in the twentieth century.

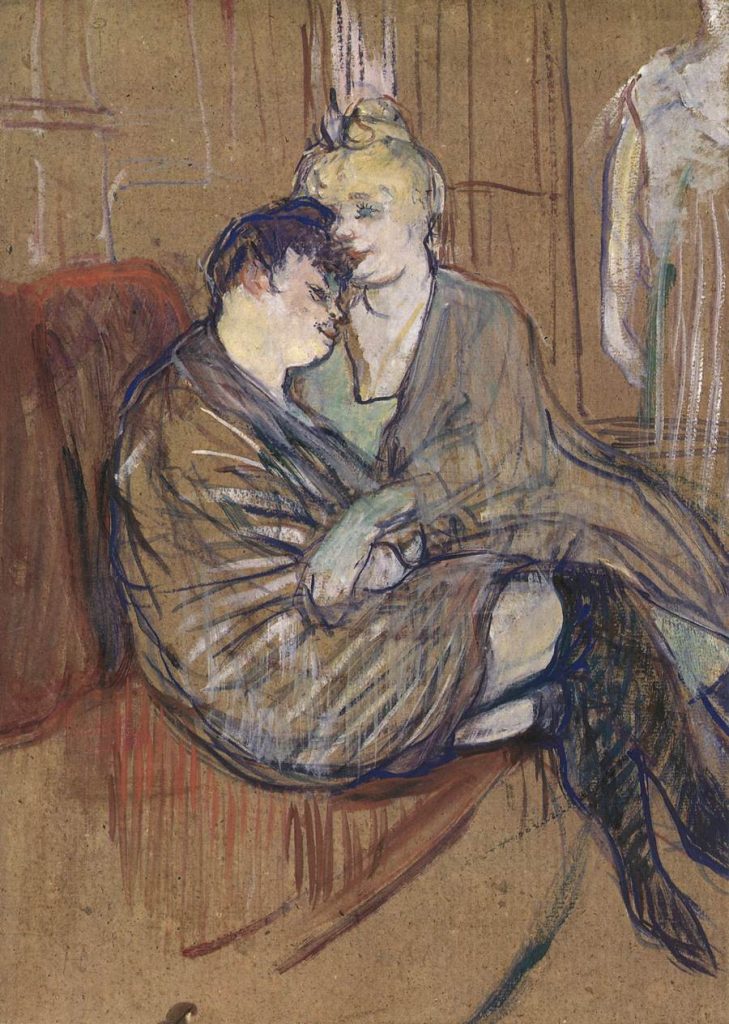

3.9

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: The Travails and Tragedies of the Ordinary Prostitute

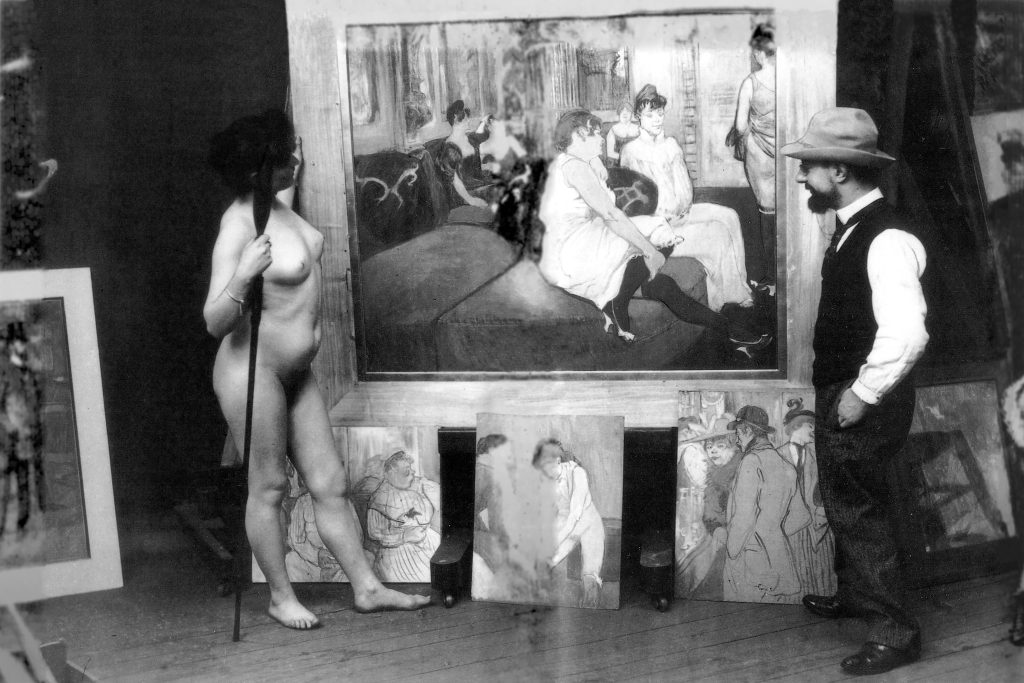

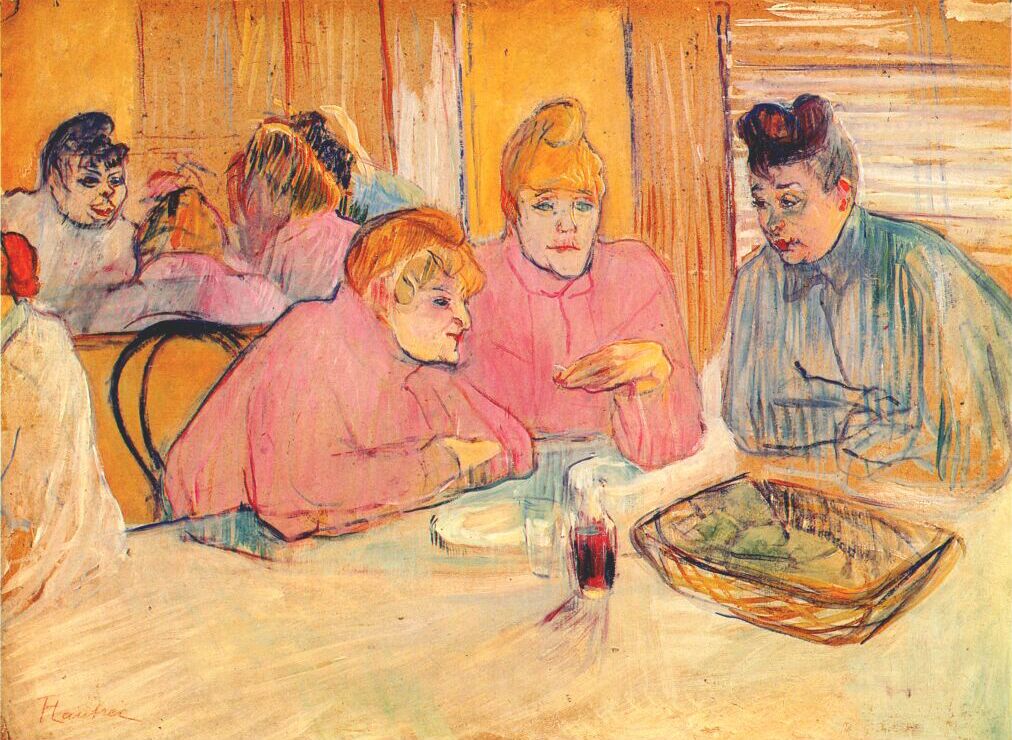

Toulouse-Lautrec’s focus on brothels as subject matter offers an approach that is different from Degas’s images of prostitution. Lautrec’s interest was in capturing the individuality of the women’s faces. He portrayed them as ordinary people going about their daily activities. Lautrec’s perspective was shaped by the fact that between 1892 and 1894 he rented a room in an upscale brothel. His sympathetic regard for the women working in that establishment was a result of this insider status.

In the early 1890s Lautrec produced roughly forty sketches, prints and paintings depicting the everyday lives of prostitutes, including the striking oil Rue des Moulins.

Lautrec’s pictures have often been discussed as reflections of a mundane, melancholy life, summed up as the artistic innovations of an aristocrat and disabled man suffering from syphilis, alcoholism and a congenital illness called pycnodysostosis, a disease characterized by skeletal malformations.

Mary Hunter in “The Waiting Time of Prostitution: Gynaecology and Temporality in Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s ‘Rue des Moulins,’” 1894 (Art History 1 (2019): 68-93), counters these interpretations with an approach that considers the painter’s imagination and engagement with artistic precedents. But unlike the brothel scenes in Edgar Degas’s monotypes from the 1870s, clients are rarely present in Lautrec’s works, and women are seldom shown soliciting men. Rather, prostitutes are portrayed as lethargic and bored, unproductive and unalluring. While a handful of the maison close pictures portray more tantalizing and intimate lesbian moments, the majority highlight the banality of brothel life; the waiting around.

Lautrec’s depiction of lesbians does not denigrate or fetishize female sexual intimacy. Instead, the artist sought to capture the tender moments in the lives of lesbian women which he conveyed truthfully and with compassion .

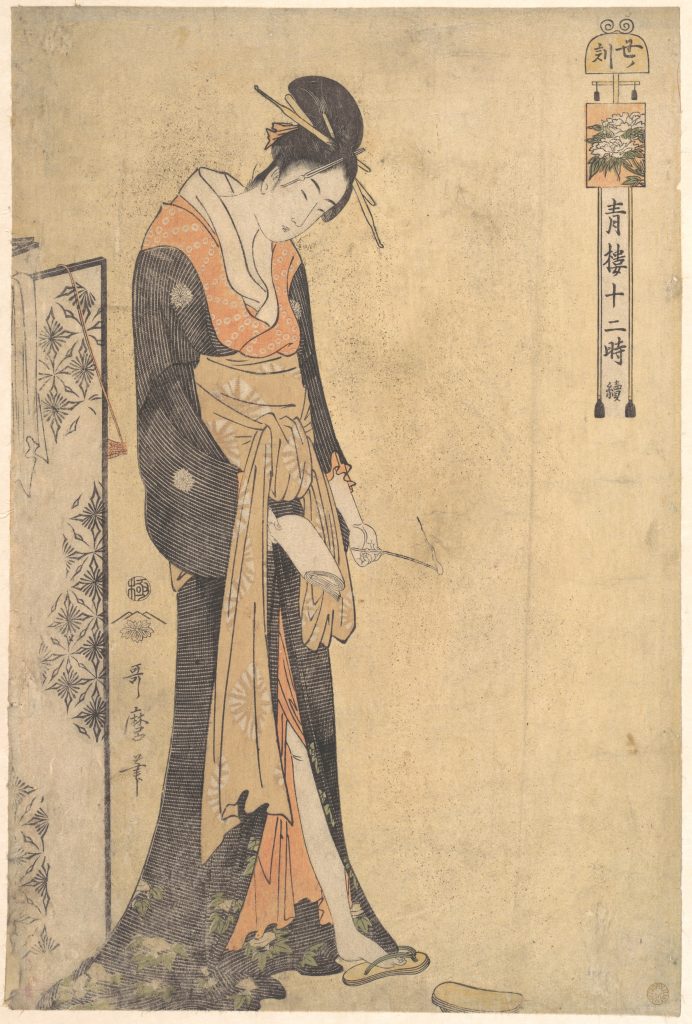

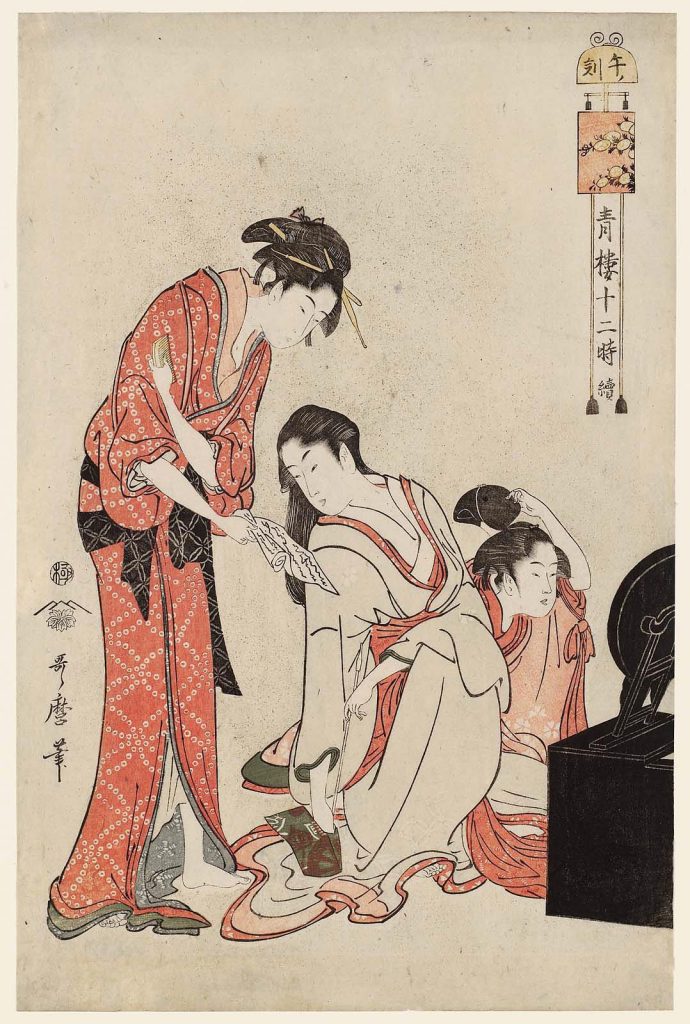

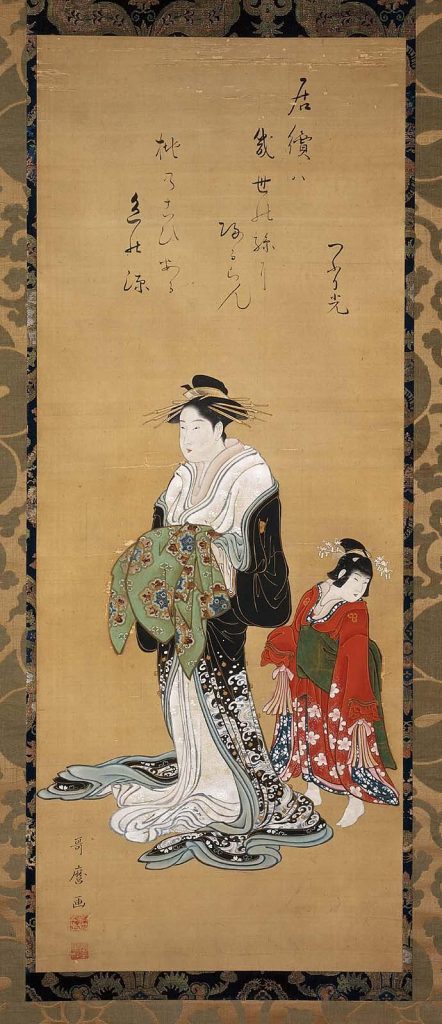

Lautrec’s pictorial depictions of the waiting-around moments of brothel-workers recall aspects of 18th century Japanese prints of sex workers that illustrated their lived realities.

Lautrec, like others of his era, was inspired by Japanese ukiyo-e erotic (shunga) prints by Kitagawa Utamaro, especially the 1794 publication entitled “Twelve Hours in Yoshiwara” containing images of courtesans in the Yoshiwara pleasure district as observed over the course of twelve hours.

The practice of selling daughters into prostitution was widely accepted in Japan. During the Edo period, the Yoshiwara district was the only place where prostitution was sanctioned. Young girls from impoverished families were sold into brothels at seven or eight, where they remained for at least a decade. The first three or four years were spent learning household chores and tending to their “sister” courtesans. During their stay, they learned etiquette, art and other skills, such as the composition of manipulative love letters and seductive conversation to attract clientele.

The formal elements of Utamaro’s prints that Lautrec attempted to assimilate were according to Hunter “the low viewpoints, outlined forms, large figures in the foreground that expand beyond the picture plane, and the erotic potential of sheer material draped over bodies while revealing limbs and flesh.” But unlike Utamaro’s courtesans who adorn themselves or otherwise prepare themselves for wealthy male clients, Lautrec’s sex workers simply wait.

As mentioned, sex workers officially registered in Paris were required to undergo routine medical inspections by the dispensaire de salubrité. As Mike McKiernan has emphasized in “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Medical Examination, Rue des Moulins (1894)” (Occupational Medicine 59 (2009): 366–368), the compulsory medical examination of brothel workers took root in France in 1810 as a tool to protect the bourgeoisie from the ravages of venereal disease. The prostitutes themselves did not benefit as their clients were never examined.

Once registered with the police des moeurs, prostitutes were either inspected by visiting physicians every eight days if they worked in the high-end maisons closes, or if they were streetwalkers, they were made to go to a neighbourhood dispensary every eleven to fourteen days. The procedures consisted of a vaginal examination using a speculum, and an inspection of a woman’s skin, hands, face, back and orifices.

>Lautrec’s Rue des Moulins, 1894, captures the ordeal of two women workers at the maisons closes as they stand in line in lifted chemises and black knee-length stockings for their turn to be examined.

Hunter:

Rendered in thin layers of oil paint on cardboard, the work shows an older blonde woman looking down blankly, her pink chemise bundled in her arms; her hunched shoulders, tired expression and sagging chin and buttocks show how time spent waiting is felt and endured. In contrast, a red-headed woman with a firm rump glares out at the viewer through the corner of her blue-hooded eye. Her scrunched-up face encrusted with built-up pink, blood orange and violet pigment, and her unnaturally bright coral-coloured ear and scalp, hint at a syphilitic state. Lautrec’s depiction of syphilis – the most widespread disease and cause of death amongst prostitutes – recalls nineteenth-century French dermatologist Henri Feulard’s description of syphilitic skin as ‘a motley mixture of colours’ consisting of ‘purplish spots’ and ‘plaques of a bright red colour, but lacking in definition of outlines.’ The prostitute’s sickly surface attracted medical and artistic gazes, and was recorded for diagnostic and aesthetic purposes. Rue des Moulins portrays a transient site – simultaneously brothel and medical waiting room – where the women’s bodies hover between the body-as-self and the worker’s and patient’s body-as-object. The instability of the scene is emphasized by the depiction of a threshold space: the central window, framed with heavy curtains, and the small light that shines through the flimsy netting, point to the outside world, while the flattened perspective and fiery red tones of the carpet, curtains and body hair present the brothel as a sensuous, enveloping interior bordering on the claustrophobic. Next to the window, the madame of the brothel’s solid, kimono-like garb contributes to this sense of enclosure, while her turned back suggests her interaction with the outside world – particularly with the clients, physicians and police who visited regularly. Private and public spheres collapse in this work as the intimate medical lives of filles publiques are put on display.

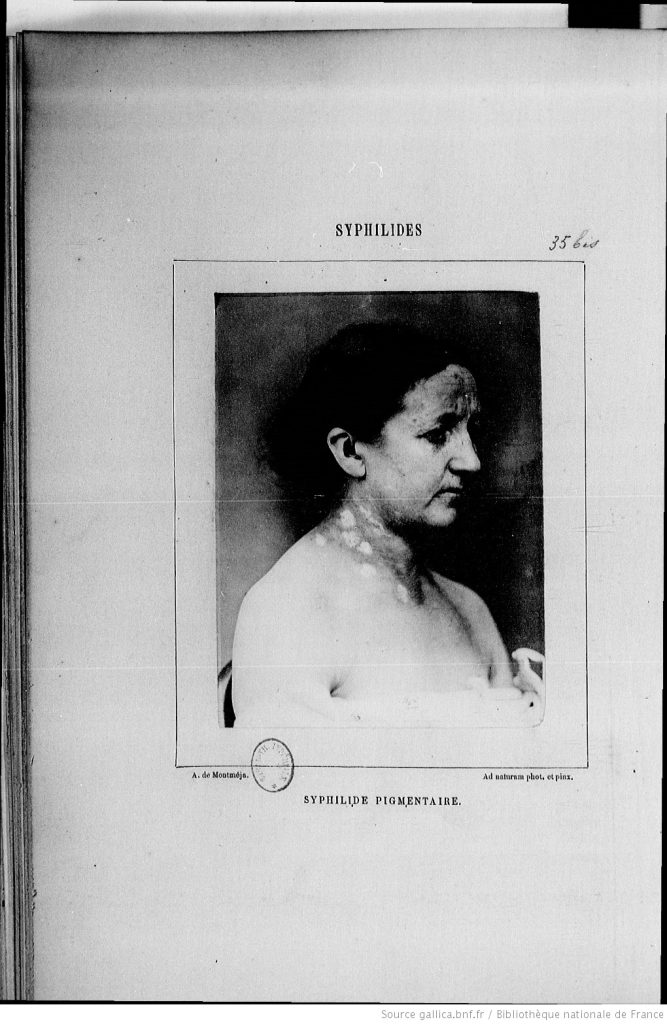

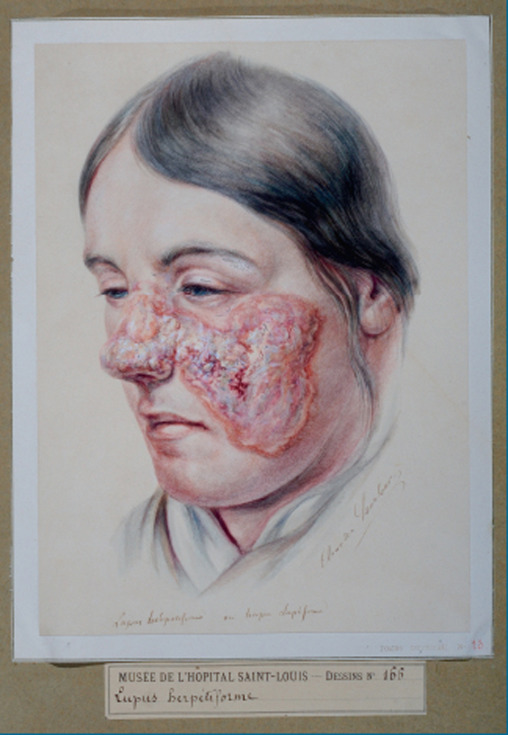

The uneven colouration of the prostitutes’ bodies in Lautrec’s image, recalls the tonal washes of early medical photo-lithographs depicting syphilis-infected patients and wax models from the Hôpital Saint-Louis, which the artist had visited with his cousin. As photographs could only be reproduced in black and white, pastel washes, white paint and spots of red were added to sepia photographs to show the stages of venereal disease to physicians and students. In Paris, syphilitic patients were often photographed upon admission to the hospital in order to record and track their illnesses over time.

In Alfred Hardy and A. de Montméja’s 1868 medical atlas Clinique photographique de l’hôpital Saint-Louis, syphilitic women exhibit poses and expressions that resemble those found in Lautrec’s paintings. The photographic headshots in the atlas seem to mimic mug-shots, thus visually documenting syphilitic women as infected, deviant and criminal. They also suggest the disease’s association with perversions and sexual anomalies in nineteenth-century medicine.

Lautrec carefully articulated the prostitutes’ profiles in Rue des Moulins, particularly the depictions of their ears, shown as large, misshapen and brightly coloured in pink and coral tones. Ears, like other orifices, indicate infection and the medical collection at the Hôpital Saint-Louis was filled with wax models of mutilated and discoloured syphilitic ears and diseased tongues, limbs and genitalia.

In 1866, Alphonse Devergie created a permanent exhibition of teaching images of skin diseases at the Hôpital Saint-Louis. In 1891 the initiative was made concrete by the inauguration of a building housing a museum, a medical library and rooms for outpatients. Enriched by the works of dermatologists, moulageurs — mainly Jules Baretta — painters and photographers, the museum became renowned worldwide for owning the most extensive wax moulages collection in the world.

Cherry Chapman describes the ravages of syphilis and how the wax models represented the stages of the disease in “A Psychotherapist in Paris: Two Very Unusual Medical Museums in Paris.” (https://www.cherrychapman.com/2014/09/22/two-very-unusual-medical-museums-in-paris/)

Each wax moulding was moulded from real patients, both adult and pediatric, who displayed skin lesions, tumors, facial and limb disfigurements, caused by the multitudes of skin afflictions. There are representations of the various stages of different diseases, from beginning to end stage. The vast majority of them were made by Jules Baretta, starting in 1867, whose artistry is breathtaking in realism. After moulding the wax to patients, he would then take notes to the exact colours noted and he faithfully reproduced exactly how they looked by painting.

Without a doubt, the most repulsive and hideous of disfigurements were caused by syphilis, seen above. Mainly caught and spread by sexual contact, or congenitally, there were recurring outbreaks starting around 1495.

3.10

| Covert Prostitution: Shopgirls and Serveuses

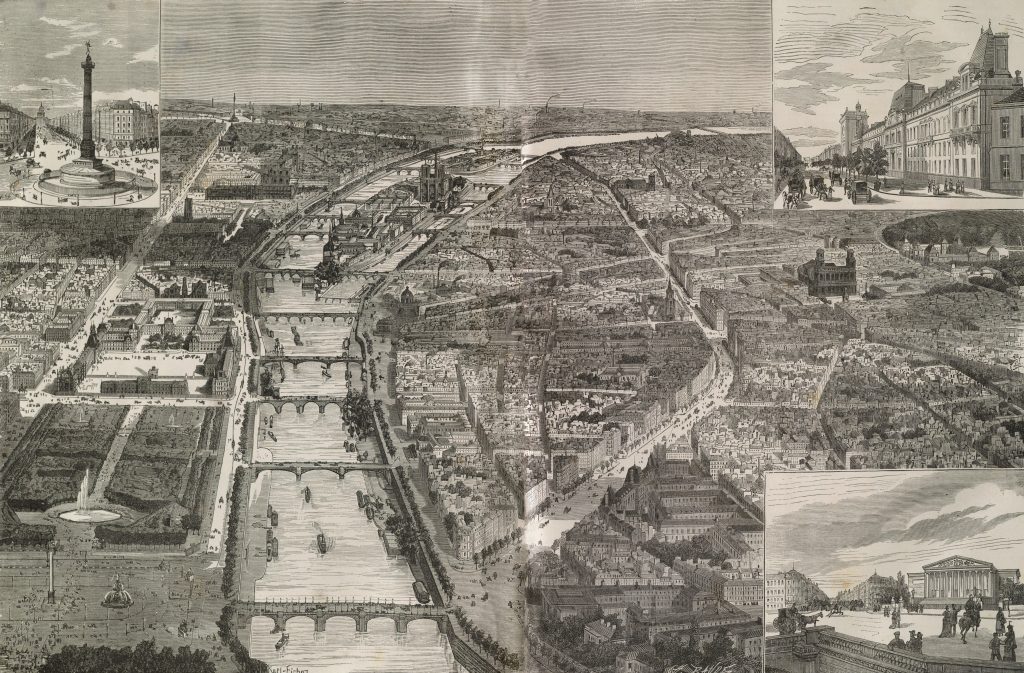

During the late 19th century Paris underwent major social changes. Under the direction of the Prefect of the Seine, Baron Haussmann, the old city buildings had been torn down and replaced by broad thoroughfares that facilitated the movement of merchandise and people. Hausmann’s public works, completed by 1870, transformed Paris into a modern city with wide boulevards, parks and squares. For example, the Rue du Jardinet on the Left Bank was demolished by Haussmann to make room for the Boulevard Saint Germain.

Renoir’s Pont Neuf, Paris captures the bright, open liveliness of the new Paris, a city of crowds and consumers. By 1877, the Bon Marché, a popular department store, employed over 3,500 staff and served 16,000 clients daily. People frequented the Paris Salons in masses; in 1884, for example, attendance was recorded at 200,000 visitors over the course of 55 days.

Nancy Forgione explains the cultural impact in “Everyday Life in Motion: The Art of Walking in Late-Nineteenth-Century Paris” (Art Bulletin 87, no. 4 (2005): 664–87):

As Paris underwent its transition to modernity, the impact of Haussmann’s changes had to be absorbed by the body as well as the eye and mind. Ingrained corporeal impulses to follow accustomed pathways had to give way to new habits and patterns of movement. To depict walking was to thematize motion. To step forth into the streets of the city was to submit oneself, willingly or unwillingly, to the urgent tempo of a distinctly urban version of lived experience. As a motif in painting, the walk offered one way of expressing the quality of that immersion.

Renoir’s Pont Neuf, Paris offers a panoramic view of midday pursuits in the busy urban centre. The city is sun-drenched, the pedestrians moving about beneath the artist’s vantage point are an eclectic group. No single incident focuses the viewer’s attention; rather, the painting offers an overall perception of the daily rhythms of a modern city in motion.

Forgione continues:

It is worth noting that a physical act of walking contributed to the making of the picture: the painter sent his brother Edmond out into the space being depicted, to stroll about and engage the passersby in conversation on the pretense of asking directions or the time, in order to slow their progress so that Renoir could sketch them more fully. Although that strategy is not apparent in the finished painting except in the fact that his brother, identifiable by his straw hat and walking stick, appears twice in the scene, such vicarious bodily activation of the visual field, in addition to its practical aim, indicates Renoir’s conception of it as a place articulated by discursive human movement.

Renoir’s painting, however, represents a privileged layer of Parisian life. Unseen is the gritty reality of industrial life and the underprivileged populace that kept it running. The urban slums of Paris were plagued by poverty at the time, a situation worsened by the flooding in of rural peasants in search of employment.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, most French women in the labour force were young, single and underprivileged. These lower-class women were stigmatized for working outside the home, regardless of their occupations. The French ideal of family life projected a clear separation between household responsibilities and the husband’s employment. By extension, the woman’s role in life was to nurture her family, literally and figuratively. The separation of spheres of activity for men and women was understood in moral, psychological and practical terms.

Female poverty was an enormous and ignored social issue in France. The journalist, Julie-Victoire Daubié, France’s first woman baccalaureate in 1861, set out to attack the socio-economic system that privileged men at women’s expense, working through her writings to promote equality between men and women in education and in the labour force.

In her book Les Femmes pauvres au XIX siècle, first published in 1866, Daubié discussed the causes of female poverty, citing three significant categories: lack of proper schooling, lack of career options, and outdated laws pertaining to the institution of marriage.

…the inadequacy of wages and the natural burden of childcare give us twice as many female beggars as male, but the women are not given as much public assistance as the men. Less numerous in hospitals, there are barely a quarter as many women as men in hospices where admittance is gained only after several years of waiting and with influential recommendations… Vagrancy, theft, vice and crime become the only means of subsistence of a large number of women and there is nothing surprising about the fact that since 1830 the number of incarcerated female mendicants has more than tripled. Over one twenty-year period, 132,000 women, among whom were a large number of sixteen-year-old girls, were also jailed for rural and forest vagrancy.

Daubié emphasized the harsh working conditions female labourers faced, a factor that led many to prostitution and strenuously criticized a system structured to “protect” privileged, decent women at the expense of the poor, whose livelihood depended on prostitution.

She went so far as to send a petition to the French Senate in June 1869, urging for the abolition of regulated prostitution and the right of women to bring paternity suits against the men who had abandoned them. Unsurprisingly the petition was dismissed.

Following the suppression of the Commune in 1871, concerns about the continuing expansion of covert prostitution flared up. Municipal systems of regulation were losing the ability to control the profession.

Almost half of the French female population was in the workforce by the end of the 19th century. While only 25 percent of them had worked outside the home in 1866, by 1896, that figure had doubled. Daughters sent out to work to supplement their family’s income often faced severe financial problems, particularly if they were obliged to work, and live, away from home. Inadequate wages and unstable conditions in the garment industry, and in domestic service led many women to engage in prostitution. Of the unregistered prostitutes arrested by the police, 39 percent reported being domestic servants, and 30 percent were sewists.

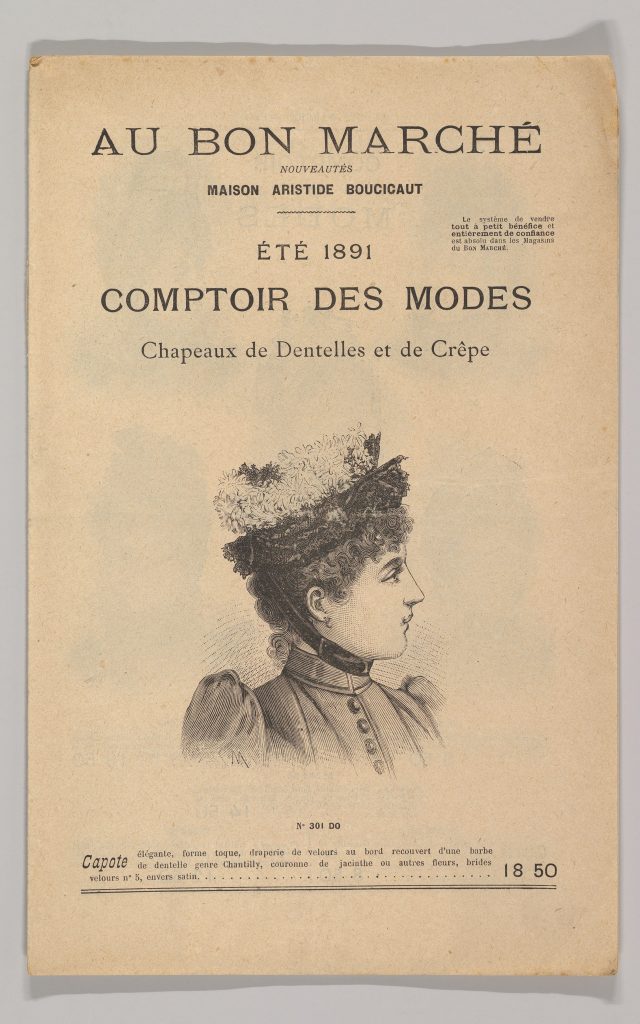

To avant-garde artists, milliners and millinery shops were an attractive subject, offering a backstory based on a significant aspect of modern life (prostitution), recognizable physical appearances and protocols, and an urban workplace. The milliner became the ideal trope of modernity, an icon of the commodified lower-class woman: a working female who made and sold objects of adornment for a living, who is also on sale herself.

Millinery was an important industry, employing about 1,000 milliners in Paris. Le Bon Marché, founded in 1838 and nearly completely reconstructed by Aristide Boucicaut in 1852, was the first modern department store and supplied Parisian women with all manner of hats essential to fashionable female attire. By the 1880s, half the employees at Le Bon Marché were women, the unmarried ones living in dormitories on the upper floors of the store.

Women’s chapeaux were a fashion statement and an indicator of status and wealth. High-end millinery shops abounded with stock which varied in price and quality. The celebrity of up-market milliners and the expense of the hats masked the workers’ low wages, particularly the appreteuse (finisher) and the petite garnisseuse (junior trimmer), who often worked 12-hour days in their ateliers. The night shift, or veillée when women would work from dusk to dawn, was a contentious issue in the garment industry, unregulated until the early 1890s.

James Tissot’s The Shop Girl depicts the interior of a millinery shop on a busy street. The door is open, and hats and accessories are seen strewn over the display tables. A young, nicely-dressed shopgirl is arranging boxes on a shelf, her stretching figure causing the bodice of her dress to cling to her frame. A middle-aged man peers in through the window. The display of goods is clearly not his interest. Although her face is unseen, the shop girl appears to engage with the man’s gaze. Tissot utilizes the cutoff composition to capture the fleeting interaction, a technique meant to show a snapshot of a modern-day scene.

When Tissot’s The Young Lady of the Shop was first shown in 1886 at the Arthur Tooth Gallery in London, the painting was described in the exhibition catalogue as follows:

It is on the boulevard; as one can see, full of life and movement is passing out of doors and our young lady with her engaging smile is holding open the door till her customer takes the pile of purchases from her and passes to the carriage. She knows her business and has learned the first lesson of all, that her duty is to be polite, winning and pleasant. Whether she meant what she says, so much of what her looks express is not the question; enough if she has a smile and an appropriate answer for everybody. (Henri Zernet, James Jacques Joseph Tissot, entry 39, in Elizabeth Pusey, “James Tissot’s and Emile Zola’s Shopgirl: The Working Girl as La Parisienne” (Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2016)

The last line implies that the shopgirl is knowing and manipulative. The surreptitious meaning is that she gets on well with the female clientele and is available to male “shoppers” as well.

Pusey:

On the shop floor, a pink ribbon can be seen haphazardly forming the shape of a heart. Tissot’s placement of the heart on the floor incites notions of a debased, perhaps degraded, love or desire….Placement of the heart and the overtly sexual gaze from the male consumer implies that like the ribbons, the shop girl is a commodity which can be illicitly purchased. The very creation and trade of clothing was viewed as morally infectious towards ‘respectable’ women, due to frequent associations of prostitution with seamstresses and shop girls. In particular, shop girls were being viewed as purchasable commodities.

There is a marked difference between Tissot’s treatment of this sexualized subject and Renoir’s At the Millinery Shop. Clayson (Painted Love, 126) provides an analysis:

… the narrative of Renoir’s painting is ambiguous and inconclusive, and the conventional identifying signs of a magasin-pretexte have been all but siphoned away. This combination of fluidity and imprecision is markedly different from Tissot’s vivid, precise, and frozen image….. It seems that Renoir was attracted to and eventually chose the motif of the millinery shop because he found social qualities in it that met his criteria for a suitably interesting subject; the appeal of female sexuality in an ambiguous, secret, and somewhat conspiratorial form, set within a public but intimate marketplace for women’s clothing.

Renoir obviously found this combination of features appealingly modern — as did Tissot. This strong appeal probably accounts for Renoir’s choice of the subject, but the way he painted it reveals his rejection of Tissot’s style of grabbing hold of and organizing the motif into something lucid, clear, and un-equivocal. Renoir’s wispy paint strokes and vibrant color interactions show him to have faced the subject — or his idea of the subject — intent on the primacy of painting, concentrating on the abstract artistic issues of translating the interaction of light and color into oil paint, of enriching black with gray, violet, and crimson, of building a composition to contain the things seen, but without forcing them into a pat and falsely legible hierarchy. It seems that Renoir’s attraction to the popular masculine eroticization of the hat shop helped to shape this picture.

That the dubious reputation of the millinery shop endowed it with a sexually tantalizing aura of ambiguity and contingency made such a place an appealing subject for a modern painting, and those equalities were carried over into the formal means of the picture. One can see Renoir converting social ambiguity into formal ambiguity. Tissot’s more definite interpretation of the motif corresponds, in turn, to his more precise way of depicting it.

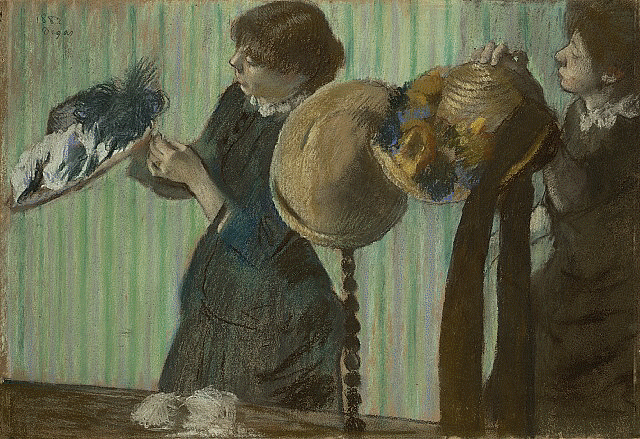

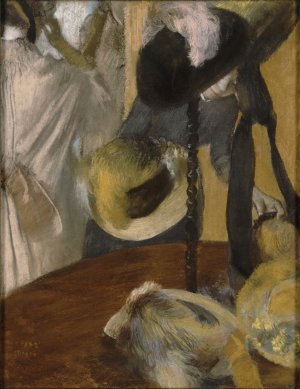

Degas’s The Little Milliners provides a further comparison. In this pastel, Degas focuses on two shopgirls; there are no customers in sight. The young women are bathed in warm tones, and the artist has used a familiar pattern of overlap and fragmentation to persuade us of the documentary accuracy of his observation. The woman on the right is not fully visible, cut off by the edge of the picture. She appears older, her features less delicate, and her observation of the other suggests she is a supervisor.

The play of relationships is purposely ambiguous; there are no erotic overtones. The possibility of a sexualized reading stems from the lore of the milliner-prostitute, the common knowledge that such shops were often sites of commercialized sex.

Degas produced twenty-seven images of millinery subjects.

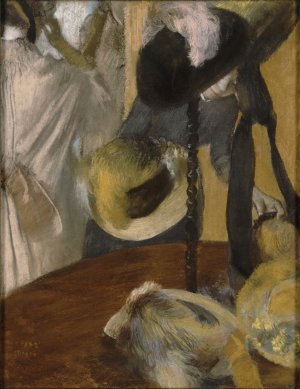

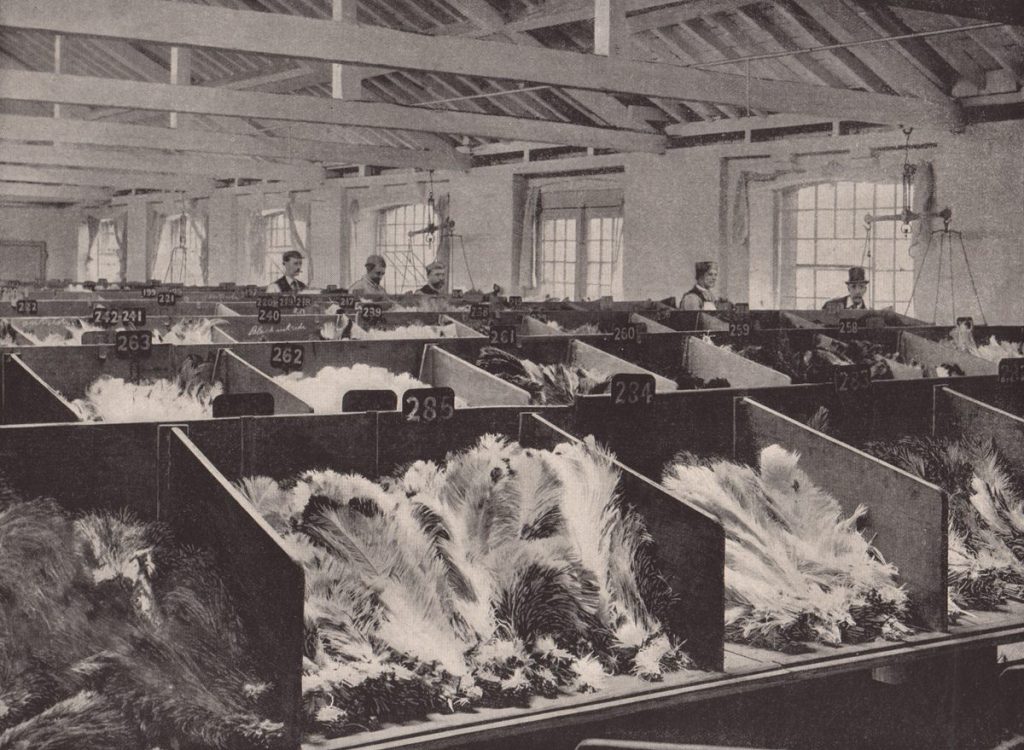

Degas’s millinery images engage with women’s labour within the context of covert prostitution and its relationship to fashion, commodity, and consumption. Simon Kelly in “‘Plume Mania’ Degas, Feathers, and the Global Millinery Trade (A Companion to Impressionism, edited by André Dombrowski (WILEY Blackwell, 2021), 425-435) provides a new perspective on Degas’s engagement with an iconography of plumage. At the Milliner’s, he writes, is “a work that is among his most innovative treatments of a millinery subject and that has been viewed as emblematic of a new Parisian culture of commodity fetishism.” In his critical analysis of the work, Kelly considers the formal and technical qualities of Degas’s image, the conditions that involved the exploitation of labourers in Paris and internationally, and the killing of millions of birds to supply the plumes for the millinery trade.

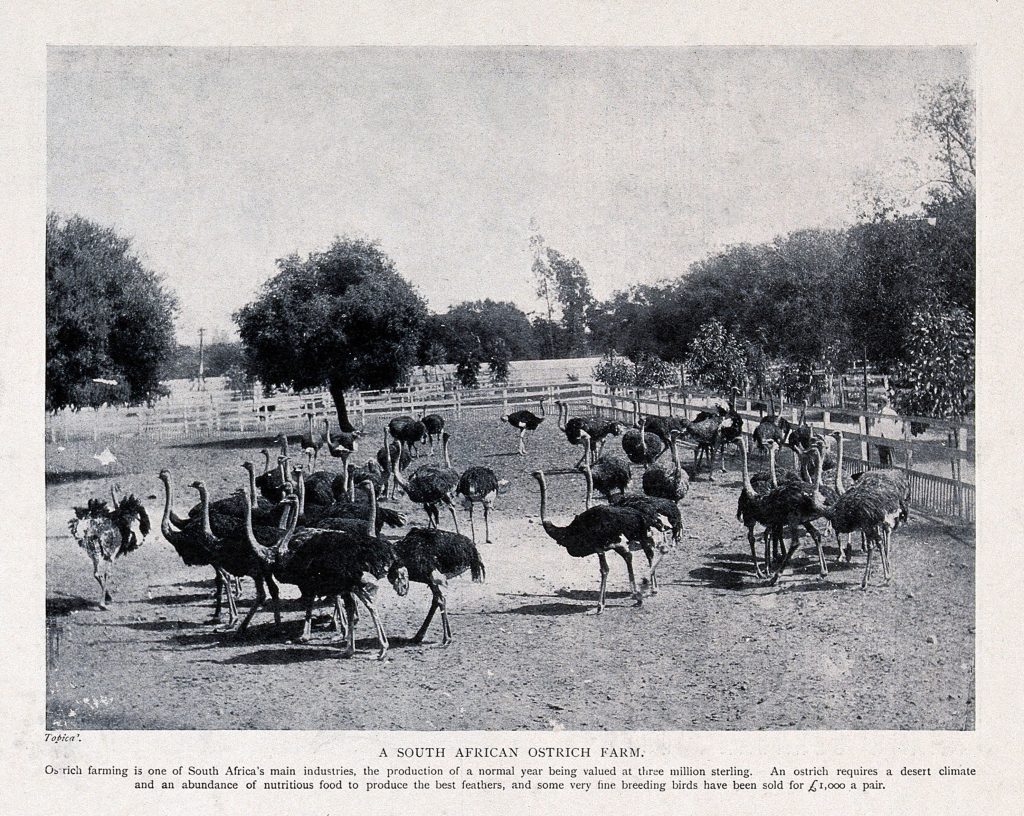

It is known that Degas painted hats in all styles and trimmings, but he was particularly drawn to ostrich plumes. In At the Milliners, the human forms are abstracted, disappearing into the overall background scheme. The artist has tilted his perspective to focus on six hats decorated in lush ostrich plumes. The hats are made of felt and straw, the colours of the plumes magnificently striking. Almost a still-life, the image is rare within the overall body of Degas’s work. The shop was likely on the Rue de la Paix, the centre for the millinery trade in Paris and a street that Degas regularly frequented.

Kelly: