What is education for sustainability?

Many contemporary social and ecological crises, including climate change, the widening gap between the rich and poor, and a significant proportion of the global population suffering from malnutrition, are perpetuated by individuals holding post-secondary education (Orr, 1991; UNESCO, 2006; in Sipos et al., 2008).

Continuing with the same educational model that contributed to these issues is unsustainable. It’s imperative to break away from educating individuals who contribute to the degradation of the planet. Instead, we should explore unconventional approaches to education.

This means we need to rethink what we teach and how we teach it. We should focus on understanding how social, economic, and environmental issues are connected and on developing skills that promote lifelong learning.

In the words of David Orr, “it is not education that will save us, but education of a certain kind” (1991, p. 51).

On this page:

Rethink what we teach

When considering incorporating sustainability content in your teaching, you can explore various instructional objectives:

Discover what it means to be a change agent and how students can self-assess here.

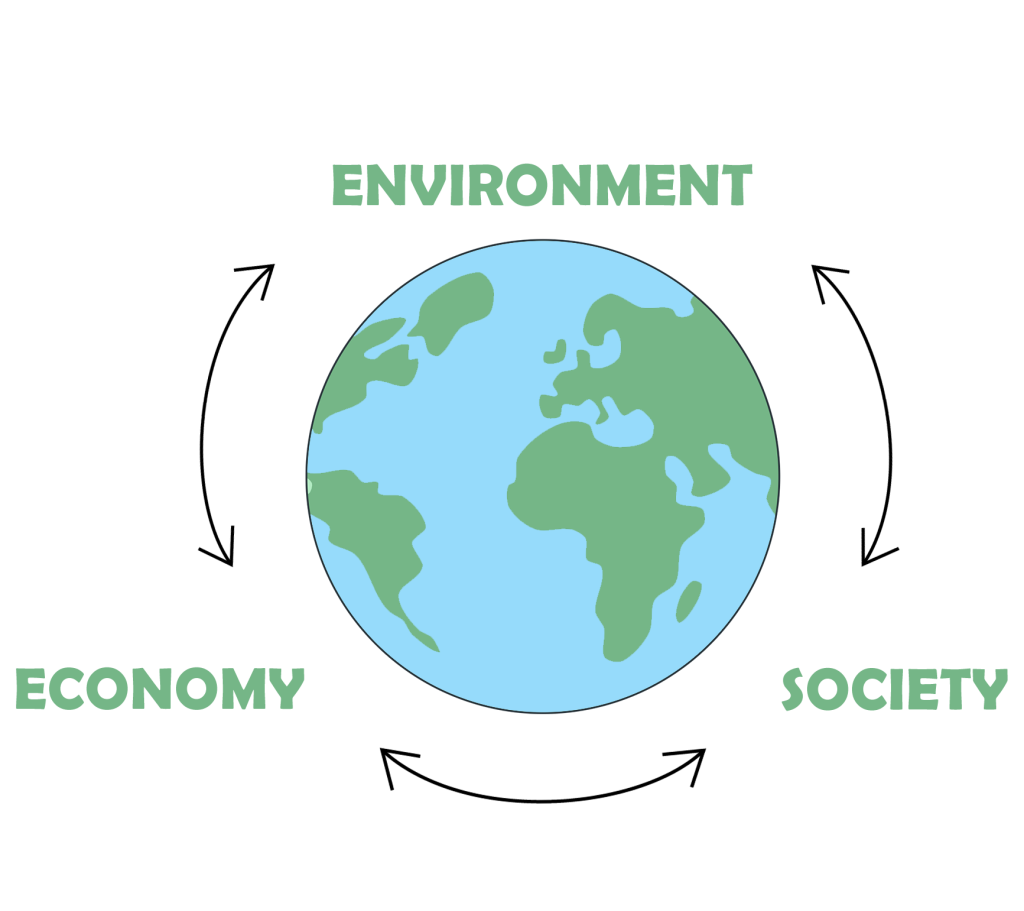

Emphasizing the Three Spheres (also known as Pillars) of sustainability – social, economic, and environmental aspects – is crucial when embedding a sustainability lens into course content. Understanding responsible resource usage is just the beginning; we must also address challenges like social justice and economic growth. Achieving a balanced approach across these pillars is essential for addressing the polycrisis that we face. In STEM fields, adding a fourth pillar, technology, is beneficial, considering its impact on sustainability.

This external webpage presents definitions and illustrations of each of the Three Pillars, along with potential actions that could be undertaken to achieve a more equitable utilization of each aspect.

These spheres are interconnected and interdependent dimensions of a larger system. Grasping this systemic view is vital, particularly for tackling issues like climate change. Students need to understand the complexity of sustainability and its holistic nature. Actions in one area can affect others, influenced by various mediating factors.

For example, technology impacts both the economy and the environment, as innovations can drive economic growth while also impacting ecosystems and natural resources. Laws and regulations can shape economic behaviour, protect environmental resources, and promote social equity. In media and communication channels, news coverage and social media campaigns may raise awareness about pressing sustainability issues, shaping public opinion, and influencing consumer behaviour.

Teaching students to critically analyze these influences can foster a systemic understanding of sustainability. Curricula should also emphasize the need to rethink relationship flows between the spheres. The question of sustainability is to consider how these relationships can be changed.

A holistic or systemic understanding will ultimately empower students to become informed and proactive agents of change in their respective fields and communities, facilitating the development of integrated solutions. Incorporating systems thinking into sustainability education is increasingly emphasized in current literature and practices, featured as one of the sustainability key competencies.

This brief video from UCLA (2021) provides a basic explanation of sustainability, emphasizing the importance of recognizing interconnectedness (or systems thinking), possibly through the Three E’s framework, wherein the social sphere is now referred to as Equity. The Three Spheres concept is also known as the Triple Bottom-Line framework.

What is Sustainability? video Copyright UCLA.

Rethink how we teach

This other type of content implies using learner-centred pedagogies, empowering the learners to think, feel and do. In learner-centred pedagogies, student learning experiences emphasize active, critical and transformative learning instead of passively absorbing information.

Some pedagogical approaches common to teaching sustainability include:

| Critical reflection supporting transformative learning | Focuses on questioning assumptions and developing new perspectives. Increases understanding of sustainability’s complexities and encourages deep self-examination to foster profound personal growth. |

| Action-oriented pedagogy | Emphasizes hands-on experiences where students take action, make decisions, or solve problems in real or simulated contexts. Empowers students towards concrete measures and to consider the tangible consequences of such actions. |

| Experiential pedagogy | Encourages students to actively engage with sustainability issues and to reflect on their learning process. Activates learning through direct experience, reflection, and conceptualization. The Office of Experiential Learning has a multitude of resources to guide educators on how to embed experiential learning in courses. |

| Interactive pedagogy | Focuses on communication and collaboration between students and with the educator serving as a facilitator. Activates learning through knowledge sharing and interaction while enhancing understanding and retention. |

| Inter- and trans-disciplinary learning | Integrates knowledge across disciplines towards a more holistic understanding. Students incorporate frameworks and concepts from multiple disciplines to examine sustainability’s interconnectedness, while developing comprehensive problem-solving skills. |

| Problem-orientation approaches (e.g., problem-based learning) | Focuses on real-world problems to drive learning. Leads students to tackle sustainability challenges, developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills. If your issue focuses on the Greater Montreal Area, CityStudio can support you. |

| Participation, peer-learning, and collaboration | Emphasizes active involvement and teamwork. Students learn from peers, fostering diverse perspectives and collective action. For guidance on how to form groups, consult our Active Learning resources. |

| Place-based and Project-based learning | Connects learning to local contexts and real-life projects. Students address sustainability issues in their community through projects, promoting practical application. They engage in land-based activities to ignite their sense of place or love for it. You might consider consulting CityStudio to help connect you with community partners, or the Indigenous Decolonization Hub for resources on land-based pedagogy. |

According to Sipos et al. (2008), additional relevant pedagogies supportive of education for sustainability are:

| Critical emancipatory pedagogy | Empowers individuals to challenge oppression and dominant narratives, foster critical thinking, promote social justice and societal transformation. Enables students to examine root causes of environmental issues, such as social inequalities, promoting system thinking. |

| Environmental education | Increases awareness of the natural world and human-environment interconnections, fostering responsibility and sustainable behaviours. It cultivates empathy for nature and comprehension of interconnected systems, empowering students to make informed decisions and champion sustainability within their lives and communities. |

| Pedagogy for eco-justice and community | Expands environmental education to include social justice principles like environmental racism and community-driven activism, fostering student agency. Students develop a holistic sustainability approach, considering social equity and inclusivity, and learn to empower communities in advocating for their rights. |

| Traditional ecological knowledge | Provides holistic wisdom passed down by Indigenous communities through generations, encompassing deep understanding of ecosystems, sustainable practices, and cultural and spiritual beliefs. Students grasp a holistic understanding of interconnected environmental issues, fostering reciprocal respect and love for nature. |

Below are examples of common activities, pedagogical tools and resources that can initiate discussions relevant to various fields of study. For further examples and applications, please refer to the section on disciplinary perspectives.

- Simulation and role play, fishbowl exercises

- Forecasting and backcasting, utopian/dystopian storytelling

- Critical and reflective thinking through discussions or reflective journals

- Real-world case studies and collaborative projects

- Carbon footprint calculators or simulators (e.g., Enroads)

- Geographic information systems

Can also be referred to as ‘student-centred’ learning or pedagogy. This educational approach prioritizes the needs and interests of the learner and encourages them to take a more active role in the learning process through interactive, experiential and collaboration.

According to the Cambridge University Dictionary (2024), a polycrisis is a “a time of great disagreement, confusion, or suffering that is caused by many different problems happening at the same time so that they together have a very big effect”. Mark et al. (2023, p.1) define a polycrisis as a “state in which multiple, macroregional, ecologically embedded, and inexorably interconnected systems face high – and advancing – risk across socioeconomic, political, and other dimensions”.