Learning activities

Use project-based learning activities and assignments that include collaboration and/or opportunities for exploring diverse perspectives (Krajcik & Blumenfeld, 2006).

Impact: Allows students to self-direct their learning. This provides opportunities to pursue individually and culturally relevant materials, helping students connect their learning to their own lives and backgrounds. In collaborative project-based learning, students can learn teamwork and cooperation by working with their peers and learning to support one another.

Example: Use project-based learning activities and assignments

In a Physics course focusing on gravitational waves, an instructor can use a group project-based learning assignment to highlight the collaborative nature of research and developments within the field. This might involve:

- First, dividing students into groups, each selecting a specialized discovery or theory on gravitational waves (e.g. Theory of Relativity, Rotating Black Holes, etc.). Second, instructing groups to research their assigned topic, focusing on the contributions of scientists from diverse cultural, ethnic, and geographic backgrounds and genders toward the topic and the dynamics of their collaboration, as well as the genealogy of ideas and research that influenced the discovery or theory chosen by the group.

- Finally, tasking each group with creating a presentation or report summarizing their findings that highlight their group’s collaboration experience, describes the dynamics of collaboration between scientists on the research topic, and critically examines the notion of individual attribution in scientific knowledge.

Explanation

Project-based learning encourages students to think critically, challenge assumptions, and ask questions in assignments and activities designed for exploration instead of finding the correct answer. Offering the element of choice permits students to seek opportunities to learn more on a subject, especially those that align with their passions, interests, and strengths. In the example provided, students can recognize the validity of different ways of approaching and thinking about a subject. Tracking the development and re-development of theories over time, including the mistakes, multiple tries, and revisions, helps to humanize the field of study by highlighting the social aspects of knowledge construction, like bias, conflict, and ego. The subject matter and nature of group work emphasize the necessity of learning to work with and understand others. Experimentation and reframing course content teach students to see the complexity of real-world issues and view topics from different perspectives, fostering a deeper understanding of the subject matter and the people around them.

Use problem-based learning activities and assignments, including case studies, that incorporate diverse cultural perspectives.

Impact: Encourages students to actively engage with different viewpoints and perspectives, promoting empathy, understanding, and respect for diversity. Focusing on real-world problems shows the practical application of course concepts to various social contexts and cultures, enabling students to see themselves represented in the learning material.

Use discussion-based learning activities that include questions to prompt an examination of a topic from varied perspectives, including providing students with a warm-up writing prompt on readings to prepare for in-class discussion.

Impact: Helps students reflect on the readings, gather their thoughts before engaging in a discussion, and feel more confident participating in class. Discussion-based activities can create a supportive environment where students share their unique perspectives and experiences. By learning to actively listen and engage with diverse viewpoints, students develop a broader understanding of their peers and build rapport with their fellow learners.

Assigning specific roles for students to guide generative class discussions and rotate these roles regularly, including students mapping interactions between speakers, noting points of confusion, tracking decisions and next actions (where applicable), and tracking emotions in discussion (where applicable; Gudjonsdottir & Óskarsdóttir, 2016).

Impact: Allows for active participation and engagement of all students, regardless of their r ability and level of comfort speaking in class. This creates multiple avenues for students to contribute to and shape class culture and learning.

Example: Have multiple roles for students during class discussions, including students mapping interactions between speakers, noting points of confusion, tracking decisions and next actions (where applicable), and tracking emotions in discussion (where applicable).

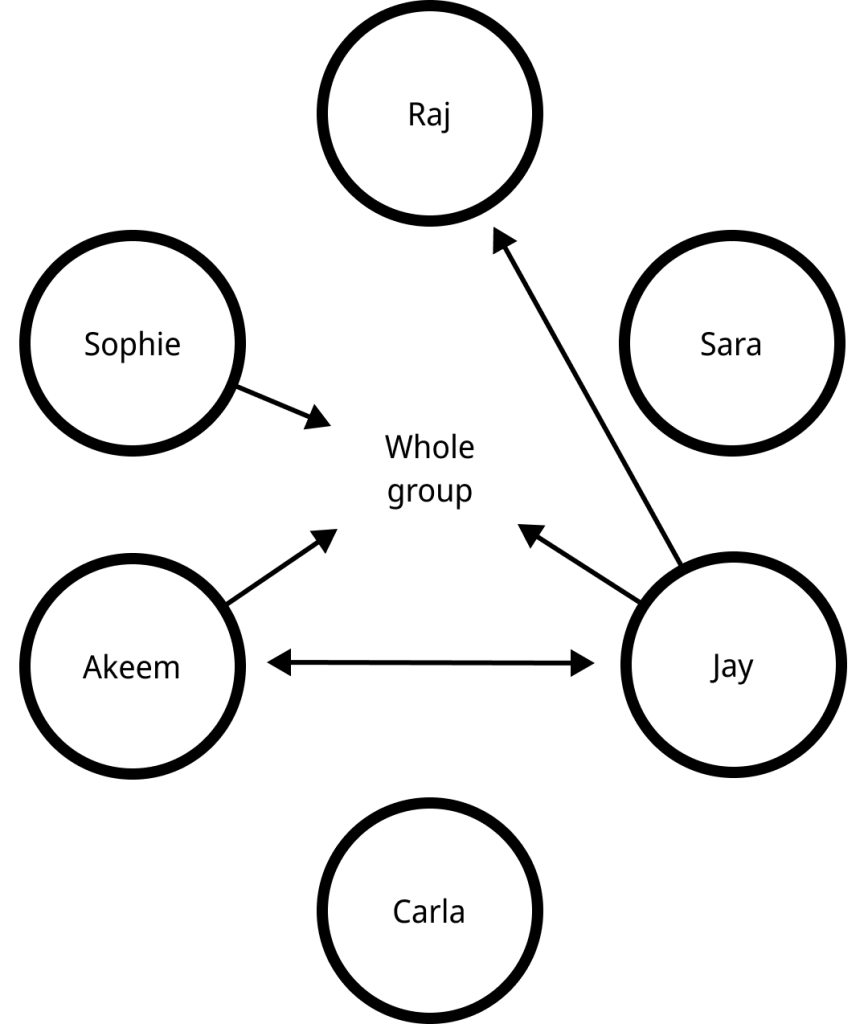

A 15-minute class discussion on The Republic of Plato (1945) can be organized to include the following roles for students.

- Six student speakers were tasked with sharing their thoughts and opinions on the assigned reading.

- One student to track the interactions between the student speakers.

- One student to track the points of confusion present over the course of the discussion.

Explanation

Tracking aspects of discussion, like exchanges of ideas, helps students recognize and reflect on how they listen to and engage with others. This can help support intentional student interactions that encourage respect and understanding between peers and build on one another’s ideas. In Figure 1, the visual representation of the discussion displays a balance between addressing the whole group of speakers and exchanging ideas between individual students. As we can see, not every student is speaking in the discussion.

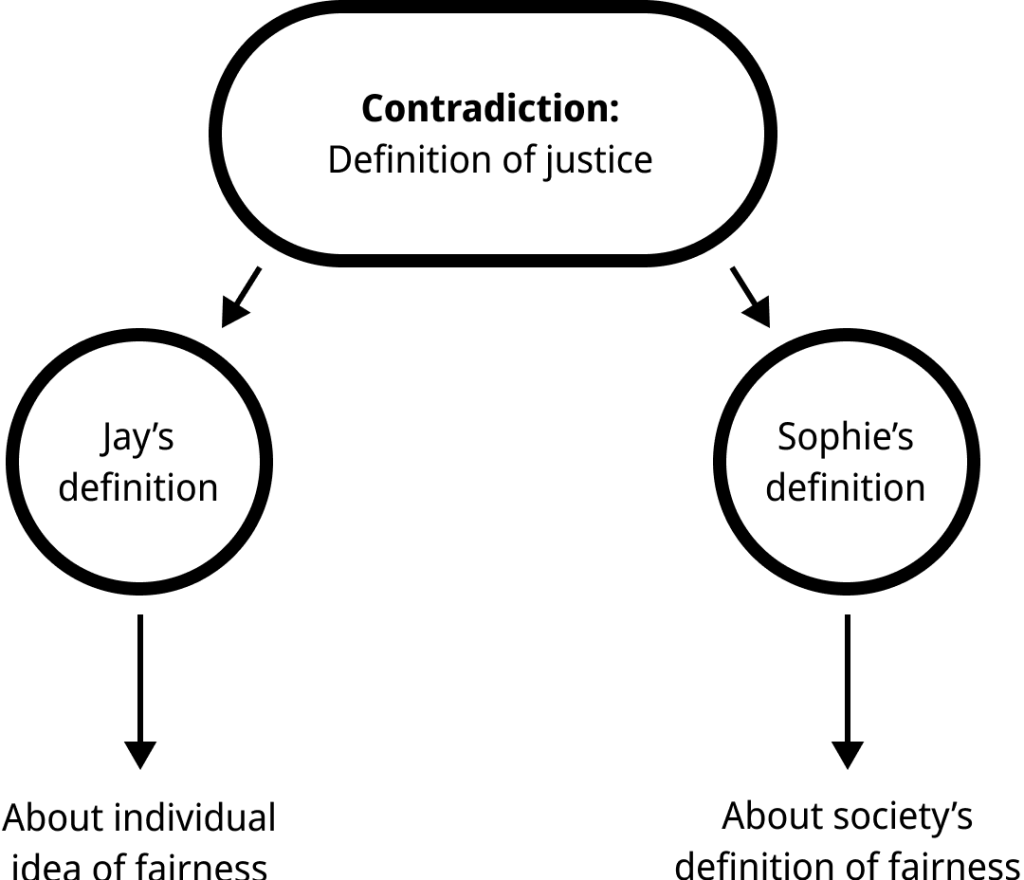

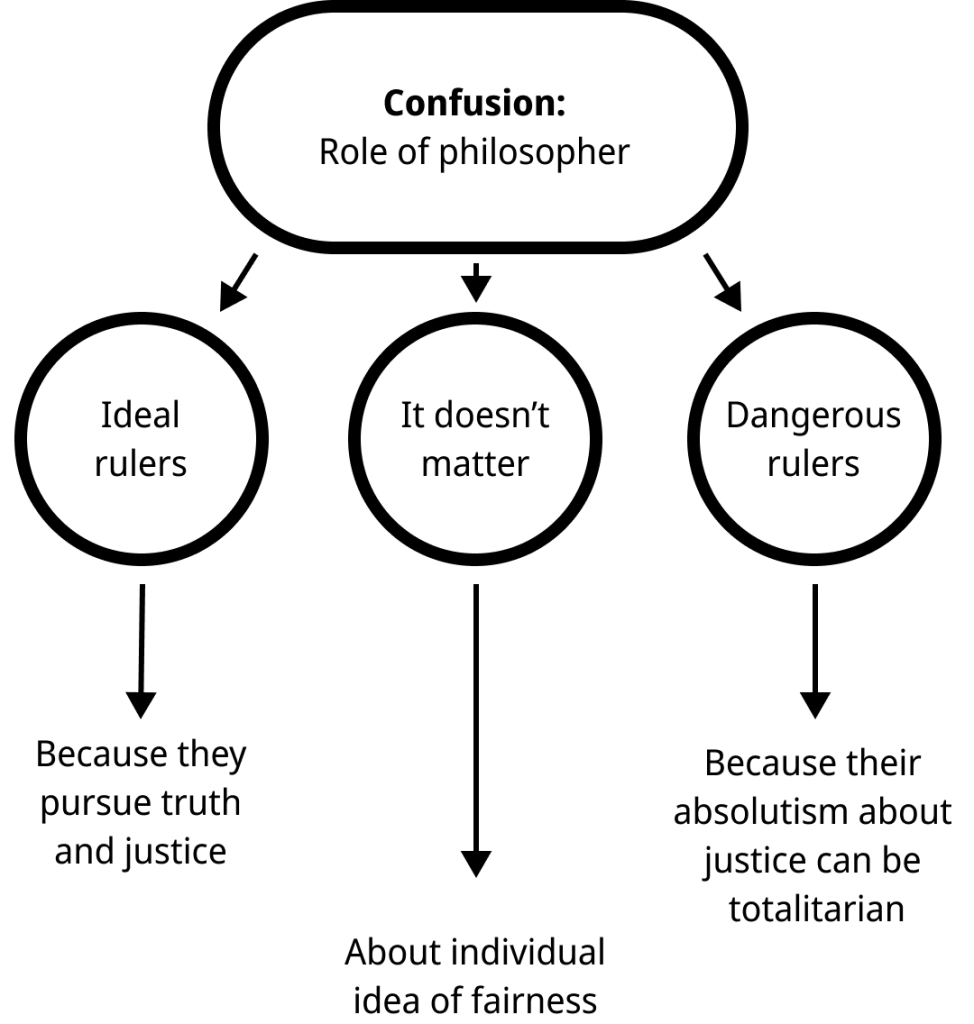

Tracking aspects like confusion highlights the role of confusion in learning while also creating a space where students’ ideas are acknowledged and supported. In Figure 2, the discussion contains contradicting ideas and questions around the comprehension of course concepts expressed. There appears to be a division in the definition of justice that leads to further confusion about the role of philosophers in Figure 3.

All of this information can be used to not only engage students but for instructors to identify struggles with course content, disengagement, and overall classroom atmosphere. Activities like these enable instructors to adjust teaching strategies to better meet the student’s needs.

Offer varied participation options, including written responses to readings and class lectures, small group discussions, and video blogs (Hogan & Sathy, 2022).

IMPACT: Provides options for students with different learning preferences and abilities, allowing students to choose the method that best suits their strengths and interests. This will enable students to build confidence and learn from each other’s perspectives by framing course content differently and engagingly. Introducing opportunities for students to select what works best for them also indicates to students that their unique backgrounds and experiences will be valued and supported.

References

Guðjónsdóttir, H., & Óskarsdóttir, E. (2016). Inclusive education, pedagogy and practice. Science education towards inclusion, 7–22.

Hogan, K. A., & Sathy, V. (2022). Inclusive teaching: Strategies for promoting equity in the college classroom. West Virginia University Press.

Krajcik, J.S. & Blumenfeld, P. (2006). Project-based learning. In Sawyer, R. K. (Ed.), the Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences. New York: Cambridge.

Plato, & Cornford, F. M. (1945). The republic of plato. Oxford University Press.