History of Psychology

Towards a Functional Psychology

Toward a Functional Psychology

While Titchener and his followers adhered to a structural psychology, others in America were pursuing different approaches. William James, G. Stanley Hall, and James McKeen Cattell were among a group that became identified with “.” Influenced by Darwin’s evolutionary theory, functionalists were interested in the activities of the mind—what the mind does. An interest in functionalism opened the way for the study of a wide range of approaches, including animal and comparative psychology (Benjamin, 2007[1]).

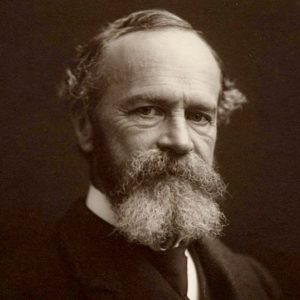

William James (1842–1910) is regarded as writing perhaps the most influential and important book in the field of psychology, Principles of Psychology, published in 1890. Opposed to the reductionist ideas of Titchener, James proposed that consciousness is ongoing and continuous; it cannot be isolated and reduced to elements. For James, consciousness helped us adapt to our environment in such ways as allowing us to make choices and have personal responsibility over those choices.

At Harvard, James occupied a position of authority and respect in psychology and philosophy. Through his teaching and writing, he influenced psychology for generations. One of his students, Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930), faced many of the challenges that confronted Margaret Floy Washburn and other women interested in pursuing graduate education in psychology. With much persistence, Calkins was able to study with James at Harvard. She eventually completed all the requirements for the doctoral degree, but Harvard refused to grant her a diploma because she was a woman. Despite these challenges, Calkins went on to become an accomplished researcher and the first woman elected president of the American Psychological Association in 1905 (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987[2]).

G. Stanley Hall (1844–1924) made substantial and lasting contributions to the establishment of psychology in the United States. At Johns Hopkins University, he founded the first psychological laboratory in America in 1883. In 1887, he created the first journal of psychology in America, American Journal of Psychology. In 1892, he founded the American Psychological Association (APA); in 1909, he invited and hosted Freud at Clark University (the only time Freud visited America). Influenced by evolutionary theory, Hall was interested in the process of adaptation and human development. Using surveys and questionnaires to study children, Hall wrote extensively on child development and education. While graduate education in psychology was restricted for women in Hall’s time, it was all but non-existent for African Americans. In another first, Hall mentored Francis Cecil Sumner (1895–1954) who, in 1920, became the first African American to earn a Ph.D. in psychology in America (Guthrie, 2003[3]).

James McKeen Cattell (1860–1944) received his Ph.D. with Wundt but quickly turned his interests to the assessment of . Influenced by the work of Darwin’s cousin, Frances Galton, Cattell believed that mental abilities such as intelligence were inherited and could be measured using mental tests. Like Galton, he believed society was better served by identifying those with superior intelligence and supported efforts to encourage them to reproduce. Such beliefs were associated with (the promotion of selective breeding) and fueled early debates about the contributions of heredity and environment in defining who we are. At Columbia University, Cattell developed a department of psychology that became world famous also promoting psychological science through advocacy and as a publisher of scientific journals and reference works (Fancher, 1987[4]; Sokal, 1980[5]).

- Benjamin, L. T. (2007). A brief history of modern psychology. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ↵

- Scarborough, E. & Furumoto, L. (1987). The untold lives: The first generation of American women psychologists. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ↵

- Guthrie, R. V. (2003). Even the rat was white: A historical view of psychology (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. ↵

- Fancher, R. E. (1987). The intelligence men: Makers of the IQ controversy. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company. ↵

- Sokal, M. M. (1980). Science and James McKeen Cattell. Science, 209, 43–52. ↵

A school of American psychology that focused on the utility of consciousness.

Ways in which people differ in terms of their behavior, emotion, cognition, and development.

The practice of selective breeding to promote desired traits.