Cultural appreciation and culturally relevant pedagogy

Inquiry cycle for culturally responsive and relevant pedagogy

Clarissa de Leon

On this page..

Introduction

Overview

Drawing on the work of Dr. Geneva Gay and Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings, this learning resource explores key concepts within Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and Culturally Relevant Pedagogy, demonstrating how they can be used in tandem to challenge dominant white narratives in higher education. Taking an inquiry approach, this learning resource will guide you through an examination of normative teaching practices within your disciplines (or institutions) and prompt you to consider how these practices may perpetuate racial hierarchies. Through a cyclical process of independent and group reflection, learning about key concepts, and practical application, you will build an understanding of how culturally responsive and relevant pedagogies can be used to disrupt and challenge power dynamics in educational spaces. Central questions participants will consider are: how can we affirm students’ cultural identities in our approaches to curriculum, classroom environment, and learning activities? How can we create accountable spaces that avoid microaggressions and tokenization? How can we encourage students to develop a socio-cultural critical consciousness?

Learning objectives

- Analyze how dominant white narratives contribute to normative teaching practices across disciplines

- Unpack points of connection and difference between Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and Culturally Relevant Pedagogy

- Identify culturally responsive and relevant pedagogies that can be used to challenge racial power hierarchies in higher education

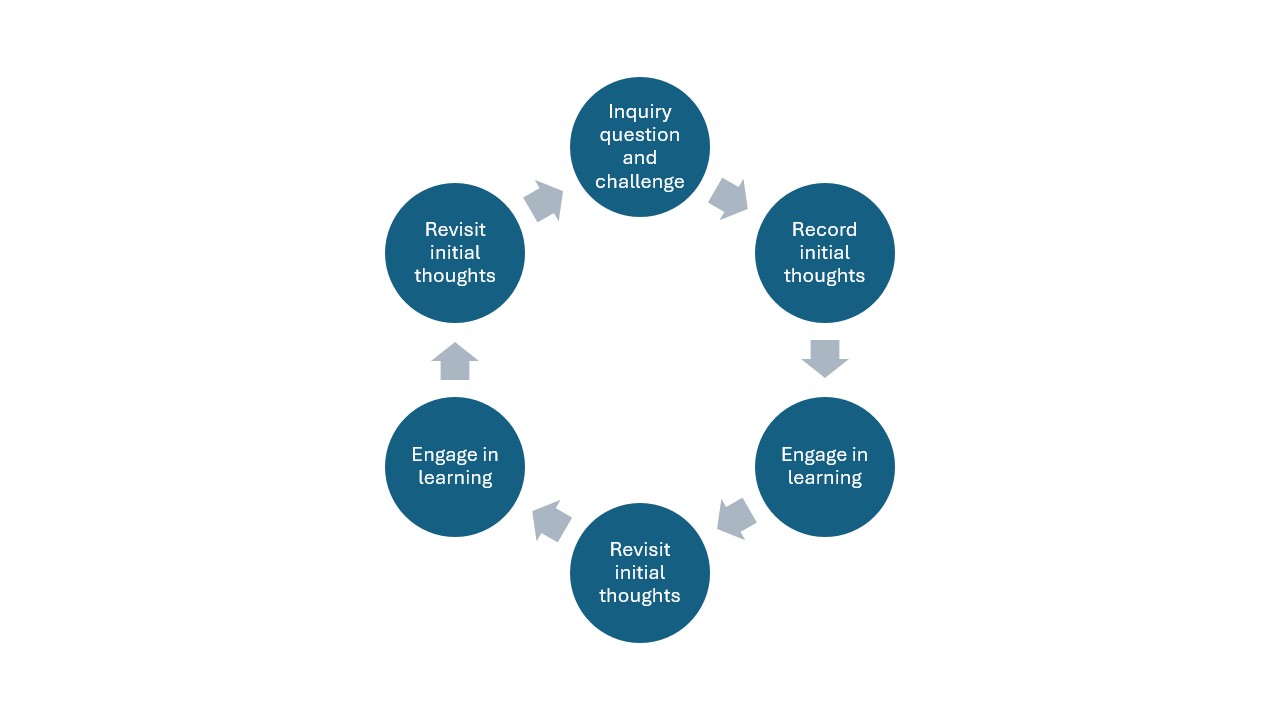

Inquiry cycle

This learning resource is structured around a cyclical inquiry approach developed by The Critical Inquiry Consortium.

The starting point for the inquiry cycle is an inquiry question and/or inquiry challenge.

Inquiry questions are ones that we grapple with over time. They resist binary thinking and singular answers and instead invite us to consider multiple perspectives on a topic. However, this does not mean that all responses to inquiry questions are equally valid or correct. An important component to inquiry questions is that responses to them can be evaluated and adapted as learners grow in their understanding of a topic and develop reasoning for their response to the inquiry question. Inquiry challenges are concrete tasks that respond to inquiry questions. They are designed to be completed within a set amount of time (e.g. a lesson, series of lessons, or in a course).

After being introduced to the inquiry question and/or inquiry challenge, learners record their initial thoughts in a thoughtbook.

Thoughtbooks

Thoughtbooks are spaces where thoughts are allowed to be messy. They are private, unstructured journals where learners can record their thinking and responses to an inquiry question and/or challenge. You are invited to use your thoughtbook whenever you like, but at key points of the inquiry cycle you will be directed to revisit it for reflective activities.

You are welcome (and encouraged) to use your thoughtbook to document your thinking in any way that feels most authentic to you including:

- Freewriting

- Bullet points

- Complete/incomplete thoughts

- Questions

- Drawings

- In any language

In this resource, steps involving the thoughtbook will be denoted by this icon:

Cycle one

Inquiry question and challenge

- Inquiry question: How may Culturally Responsive and Relevant Pedagogies help us thoughtfully and intentionally support racialized students?

- Inquiry challenge: Identify a strategy you can adapt and a strategy that you can adopt to be more culturally responsive and relevant in your practice

Record initial thoughts

Using your thoughtbook, record your initial thoughts about the inquiry question and challenge using the below table.

| What are my staple teaching practices? | What do I want to start doing? |

|

|

Engage in learning

In the “Engage in learning” portions of the inquiry cycle, you will be introduced to key concepts connected to the inquiry question and challenge. In this section you will explore ideas related to Critical Race Theory (CRT) and curricular violence. You will also be provided with resources to explore, and reflection prompts to consider independently and/or with others (e.g. colleagues).

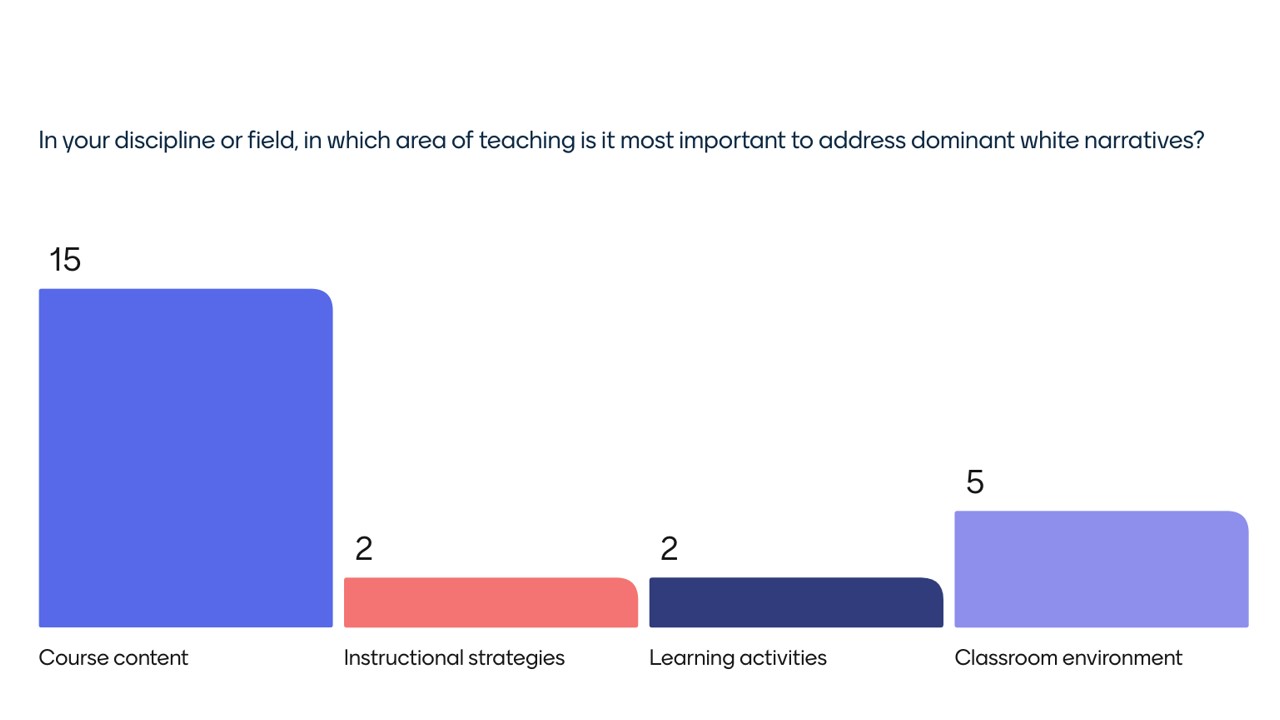

Consider: In which areas of your discipline or program is it most important to address dominant white narratives through your teaching?

- Course content

- Instructional strategies

- Learning activities

- Classroom environment

Here is what attendees at the Contemplative Summit had to say:

How do these responses align with your answer? Do the results surprise you? Why may others have the same or a different response to you?

All the above options can be considered a valid selection depending on your specific context. This is because dominant white narratives can be present in all aspects of teaching across all disciplines due to systemic racism. Critical Race Theory (CRT) can help us better understand the systemic nature of racism.

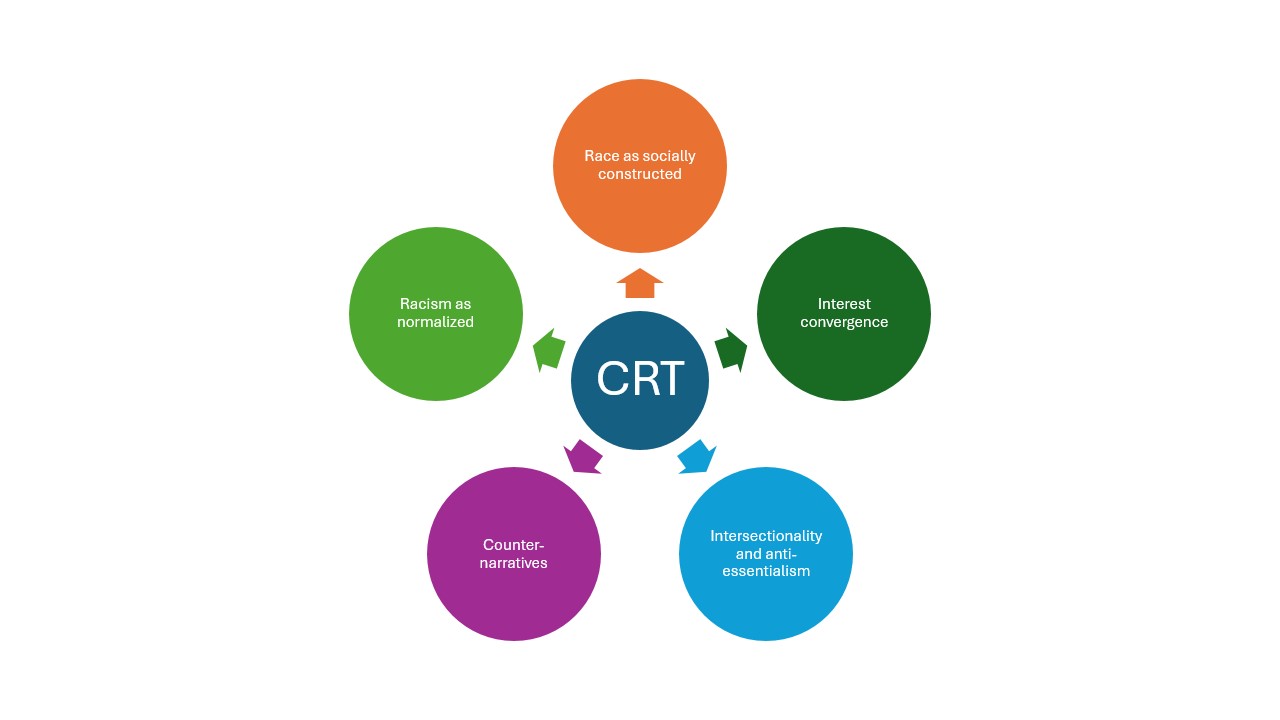

The origin of CRT is in critical legal studies. CRT is a theoretical framework that argues that race is socially and legally constructed to advance the interests of white people at the expense of Black, Indigenous, and people of colour. As such, race and racialization are embedded in structures within and across institutions such as the legal system, education, health services, and housing. While there is some variation amongst CRT scholars on how they discuss or theorize about systemic racism, there are a set of generally agreed upon tenets of CRT:

(see Additional resources section to learn more about CRT)

Of the abovementioned CRT tenets, racism as normalized is of particular importance to consider when endeavoring to address dominant white narratives in teaching. The normalization of racism helps explain the ways whiteness can be centered in both what and how we teach. A concept that can help illustrate this point is curriculum violence (Jones, 2020). According to Jones, “curriculum violence occurs when educators and curriculum writers have constructed a set of lessons that damage or otherwise adversely affect students intellectually and emotionally” (para. 7).

The adverse effects curriculum violence can have on students can be felt from various aspects of lessons and teaching. CRT explains that curriculum violence often goes unnoticed because practices that center and privilege whiteness are conveyed as normative or “just the ways things are.”

Consider: What status quo educational practices in your discipline perpetuate curriculum violence? You are encouraged to discuss this question with a colleague in your field or discipline. Remember, curriculum violence can manifest in different ways including:

- Course content: What ideas are implicitly and explicitly reinforced?

- Instructional strategies: Whose perspectives and knowledges are centered?

- Learning activities: In what ways and how are students engaged in their learning? How are students assessed?

- Classroom environment: How do students share space? Whose needs are prioritized?

Return to your thoughtbook

Revisit your thoughtbook and re-read your initial thoughts from the beginning of the inquiry cycle. What do you think now? Feel free to add or remove ideas, ask further questions, build on initial thoughts, or anything else you wish to record.

Revisit your thoughtbook and re-read your initial thoughts from the beginning of the inquiry cycle. What do you think now? Feel free to add or remove ideas, ask further questions, build on initial thoughts, or anything else you wish to record.

Engage in learning

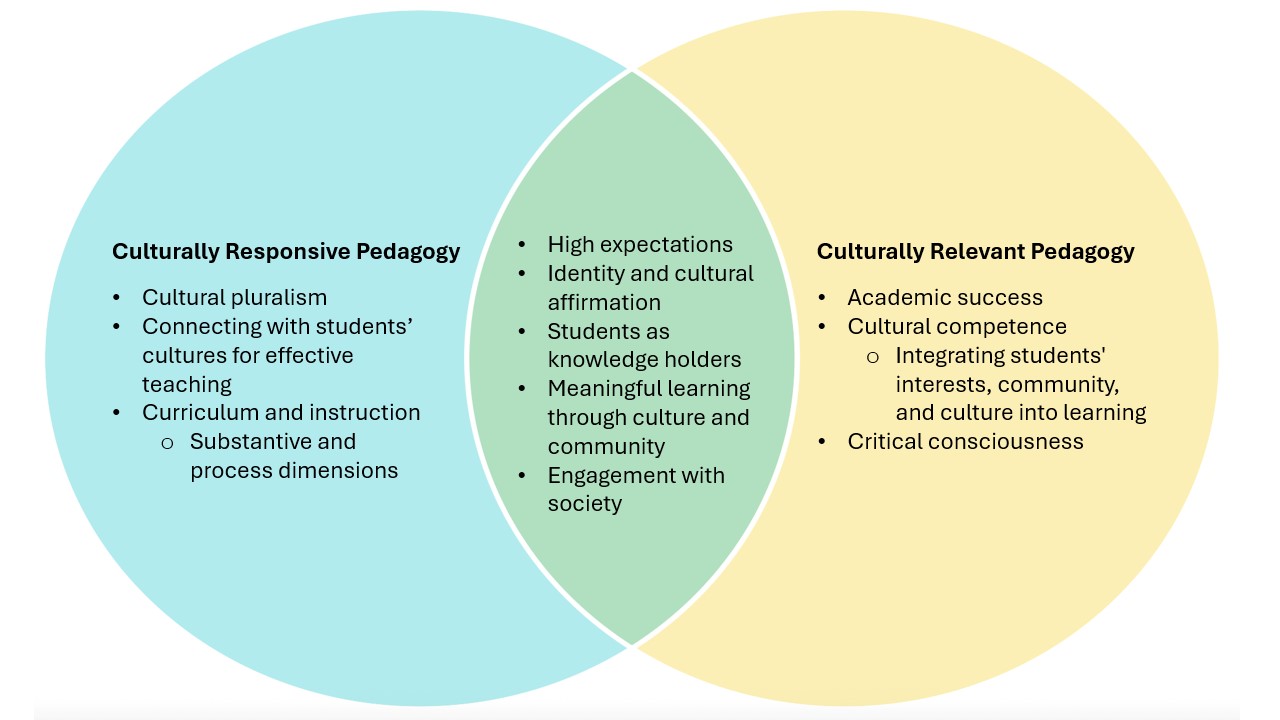

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and Culturally Relevant Pedagogy are two approaches to education that can help educators address and decenter white narratives in teaching and learning. Though sometimes used interchangeably, Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and Culturally Relevant Pedagogy are two distinct frameworks and offer different perspectives on supporting racialized students.

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy emerged out of research on multicultural education and was developed by Dr. Geneva Gay. In Culturally Responsive Pedagogy, educators aim to more effectively teach diverse student populations by drawing upon their heritages, experiences, and perspectives. According to Gay (2018):

Culturally responsive teaching corrects this misconception and exclusion by making explicit how and why mainstream educational policies and practices are shaped by and reflective of the Eurocentric culture, perspectives, and experiences of the powerful, privileged, and demographically dominant ethnic group. In other words, what is commonly thought of as cultureless mainstream U.S. schooling is, in reality, Eurocentric culturally responsive education.” (p. 86-87)

Key characteristics of Culturally Responsive Pedagogy include constructivism, building on prior knowledge, educators developing a deep knowledge of students, and teachers growing their own awareness of diversity in their classroom and larger social contexts. See Additional resources section to learn more about Culturally Responsive Pedagogy.

Culturally Relevant Pedagogy emerged out of research on Culturally Responsive Pedagogy as well as Critical Race Theory. In Culturally Relevant Pedagogy, educators focus on helping students achieve academic success while also affirming their cultural identities and encouraging them to question and challenge social inequities. According to Ladson-Billings (2024),

The genesis for this inquiry came from my observation that, although teachers had access to increasingly diverse curriculum materials such as textbooks, trade books, curriculum units, classroom posters, and decorations, the students from marginalized racial and ethnic groups were continuing to struggle to achieve academic success. These materials were not changing the ways teachers approached teaching.” (p. 99)

The key tenets of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy are academic success, cultural competence, and critical consciousness. (see Additional resources section to learn more about Culturally Relevant Pedagogy).

Consider:

- How may culturally responsive teaching and culturally relevant teaching be similar? How may they be different? How can normative practices in your discipline be re-molded to have a more culturally responsive and relevant approach? You are encouraged to discuss these questions with a colleague from your discipline. Together, identify examples specific to teaching in your field. Use the Venn diagram below to guide your thinking.

- Both Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and Culturally Relevant Pedagogy have their origins in kindergarten to grade 12 education. However, the ideas and core concepts in both frameworks can transfer to higher education. To expand your thinking about culturally responsive and relevant teaching approaches, read Culturally Relevant and Responsive Pedagogy in the Early Years: It’s Never Too Early! (McAuley, 2018).

Return to your thoughtbook

Revisit your thoughtbook and re-read your entries. What do you think now? Feel free to add or remove ideas, ask further questions, build on initial thoughts, or anything else you wish to record.

Revisit your thoughtbook and re-read your entries. What do you think now? Feel free to add or remove ideas, ask further questions, build on initial thoughts, or anything else you wish to record.

Cycle two

Inquiry question and challenge

Reground yourself in our inquiry question and challenge:

- Inquiry question: How may Culturally Responsive and Relevant Pedagogies help us thoughtfully and intentionally support racialized students?

- Inquiry challenge: Identify a strategy you can adapt and a strategy that you can adopt to be more culturally responsive and relevant in your practice

Return to your thoughtbook

Re-read the entirety of your thoughtbook. After re-reading, circle one strategy from each column of your table:

| What are my staple teaching practices? | What do I want to start doing? |

|

|

How culturally responsive and relevant are your two selected pedagogical strategies? Based on what you have learned, how might you adopt and adapt them as methods for disrupting dominant white narratives in your teaching?

Engage in learning

Try your selected strategies relatively soon (within the next two weeks if possible). If you are not currently in a teaching role, consider organizing an opportunity for you to teach to a group of colleagues or peers (e.g. microteaching). If it is helpful, use the below guide to plan when and how you will implement these strategies, as well as your reflection immediately after using the strategies.

| Topic | Plan |

|

|

|

| Materials | |

|

|

|

| Reflection | |

| What did you notice about how students responded to their learning? What did you notice about how you responded to their learning?

|

|

You may also consider having a colleague observe you teach.

Return to your thoughtbook

Revisit your thoughtbook and re-read your entries. What do you think now? Feel free to add or remove ideas, ask further questions, build on initial thoughts, or anything else you wish to record.

Revisit your thoughtbook and re-read your entries. What do you think now? Feel free to add or remove ideas, ask further questions, build on initial thoughts, or anything else you wish to record.

Engage in learning

Further investigate the culturally responsive and relevant strategies you implemented in your teaching. What research has been done on these strategies? What do scholars in your field say about teaching and learning in your discipline? How has Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and Culturally Relevant Pedagogy been incorporated in disciplines outside of your own? You may consider using the below graphic organizer to help organize your research.

| Research on Culturally Responsive and Relevant Pedagogy | Research on teaching and learning in your discipline |

Topic

|

Topic

|

Topic

|

Topic

|

Return to your thoughtbook

Revisit your thoughtbook and re-read your entries. What do you think now? Feel free to add or remove ideas, ask further questions, build on initial thoughts, or anything else you wish to record.

Revisit your thoughtbook and re-read your entries. What do you think now? Feel free to add or remove ideas, ask further questions, build on initial thoughts, or anything else you wish to record.

Carrying the cycle forward

Now that you have completed two cycles of the iterative inquiry process, you can continue the process with the same inquiry question and challenge, or you can take this opportunity to develop a new inquiry question and challenge based on your emerging interests and observations. You may consider:

- What needs have you observed from your students?

- What challenges or resistance could you encounter when taking a culturally responsive and relevant approach?

- What is the culture of your institution? Of your discipline? How may that affect the teaching strategies you use?

- What are your personal areas of growth in relation to anti-racist learning?

Additional resources

Critical Race Theory

Beecham, M. (2022, November 15). Critical race theory 101: The 5 basic ideas you need to know (No. 5) [Audio podcast episode].

Delgado, R., Stefancic, J., & Harris, A. (2012). Critical race theory: An introduction (Second). NYU Press.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2013). Critical race theory—What it is not! In M. Lynn & A. D. Dixson (Eds.), Handbook of critical race theory in education (1st ed., pp. 34–47). Routledge.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2024). How pedagogy makes the difference in U.S. schools. Daedalus, 153(4), 96–110. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_02106

Ray, V. (2023). On critical race theory: Why it matters & why you should care. Random House.

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

EHE Distance Education and Learning Design (Director). (2015, October 8). Dr. Geneva Gay and Dr. Valerie Kinloch interview [YouTube Video].

Gay, G. (2015). The what, why, and how of culturally responsive teaching: International mandates, challenges, and opportunities. Multicultural Education Review, 7(3), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615X.2015.1072079

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. In Teachers College Press. Teachers College Press. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED581130

Culturally Relevant Pedagogy

Ladson‐Billings, G. (1995). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Into Practice, 34(3), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849509543675

Ladson-Billings, G. (2024). How pedagogy makes the difference in U.S. schools. Daedalus,153(4), 96–110. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_02106

Valdelièvre, M. (2021, August 11). Culturally relevant pedagogy can save a bad curriculum: In conversation with Gloria Ladson-Billings [Audio podcast episode].

References

Click to expand reference list

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. In Teachers College Press. Teachers College Press.

Jones, S. P. (2020). Ending curriculum violence.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2024). How pedagogy makes the difference in U.S. schools. Daedalus, 153(4), 96–110. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_02106

a theory of learning that believes learning happens through active engagement in experiences and interactions.