Stress and Health

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

What is Stress?

Stress, a prevalent aspect of modern life, especially for university students grappling with academic pressures, financial burdens, and personal challenges, is a complex phenomenon influenced by both external situations and our internal responses. It encompasses a range of experiences from feeling overwhelmed by exams and deadlines to navigating societal pressures, all of which can significantly impact our mental and physical health. Broadly defined, stress can be viewed from two perspectives: specific external triggers or our physical and emotional reaction to these demands (Lyon, 2012), underscoring the intricate interplay between our environment and how we perceive and cope with challenges.

The term stress, as it relates to the human condition, first emerged in scientific literature in the 1930s, but it did not enter our everyday language until the 1970s (Lyon, 2012). Today, we often use the term loosely in describing a variety of unpleasant feeling states; for example, we often say we are stressed out when we feel frustrated, angry, conflicted, overwhelmed, or fatigued. Despite the widespread use of the term, stress is a fairly vague concept that is difficult to define with precision.

Researchers have struggled to agree on an acceptable definition of stress. Broadly, there are two primary ways of conceptualising stress: (1) the stimulus-based definition and (2) the response-based definition. The stimulus-based definition views stress as a result of specific external events or situations, such as a high-stress job or long commutes, which act as stimuli, triggering stress reactions. However, this approach has been critiqued for not accounting for individual differences in perception and reaction to these stimuli. On the other hand, the response-based definition focuses on the physical and emotional responses that occur when faced with demanding or threatening situations, like increased arousal. This perspective emphasises the physiological aspect of stress but can overlook the fact that such responses can also be triggered by positive or non-threatening events.

How to Cope with Stress

While there are many different ways to cope with stress, the coping strategies are usually grouped into two categories: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. Problem-focused coping puts an emphasis on finding a solution to the problem at hand (Folkman, 2013). You might look for information, ask for advice, or problem-solve. On the other hand, emotion-focused coping allows you to deal with the emotions that result from the stress. Some strategies include asking for support, using humor to make light of the situation, or daydreaming. Both kinds of coping have their pros and cons, depending on how they are used. When a situation can be controlled, problem-focused coping is more often used. For instance, if you are stressed about an exam, taking time to study in advance can help you cope with the stress. However, in a situation that cannot be influenced, such as the passing of a family member, it is better to accept and cope with the situation by using emotion-focused coping. People generally use a mix of these strategies and tend to switch between them depending on the situation (Folkman, 2013).

Stress: The Good and the Bad

Stress is often seen as something negative, but it can also be helpful. Stress can push us to do important things like study for exams, go to the doctor, exercise, and work hard. Selye, a scientist in 1974, said that stress isn’t always bad. He explained that stress can be a good thing that helps improve our lives. He called this good stress “eustress” (from a Greek word meaning “good”). Eustress is the kind of stress that makes you feel positive and can be good for your health and performance.

A moderate amount of stress can be beneficial in challenging situations. For example, athletes may be motivated and energised by pre-game stress, and students may experience similar beneficial stress before a major exam. Indeed, research shows that moderate stress can enhance both immediate and delayed recall of educational material. Male participants in one study who memorised a scientific text passage showed improved memory of the passage immediately after exposure to a mild stressor as well as one day following exposure to the stressor (Hupbach & Fieman, 2012).

But when stress exceeds this optimal level, it is no longer a positive force; it becomes excessive and debilitating, or what Selye termed distress (from the Latin dis = “bad”). People who reach this level of stress feel burned out; they are fatigued and exhausted, and their performance begins to decline. If the stress level remains excessive, health may begin to erode as well (Everly & Lating, 2002).

Stress and Performance

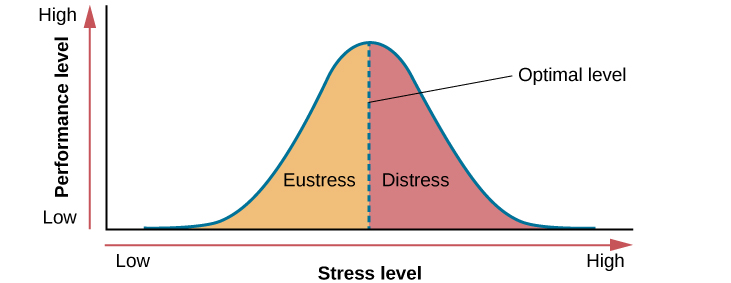

Figure WB.2 shows us that as stress increases, so does performance and well-being, up to a point. This is eustress. When stress reaches the best level (the highest point of a curve), performance is at its best. You feel fully energised and focused, and you work efficiently. But if stress goes beyond this best level, it becomes too much and harmful; this is distress. People with too much stress feel burned out and tired, and their performance drops. If the stress level stays too high, it can even harm health. For example, students who are very stressed about a test might find it hard to concentrate, which can affect their test scores.

A graph features a bell curve that has a line going through the middle labeled “Optimal level.” The curve is labelled “eustress” on the left side and “distress” on the right side. The x-axis is labeled “Stress level” and moves from low to high, and the y-axis is labeled “Performance level” and moves from low to high.” The graph shows that stress levels increase with performance levels and that once stress levels reach optimal level, they move from eustress to distress.

Stress in Our Lives

Stress is a common experience. We all deal with it in different ways. It can feel like a heavy load, like when you have to drive in a blizzard, wake up late for an important job interview, run out of money, or aren’t ready for a big test. Stress is an experience that can include symptoms like a faster heart rate, headaches, gastrointestinal problems, and difficulty concentrating or making decisions. We may react to stress in unhealthy ways by drinking alcohol, smoking, or engaging in other dubious behaviours we hope will reduce the stress. While stress can sometimes be good, it can also lead to health problems, contributing to illnesses and diseases. Stress can cause physical reactions like a fast heartbeat or headaches, make it hard to think or decide, and lead to behaviours like drinking or smoking.

Health Psychology and Stress

The scientific study of how stress and other psychological factors impact health is part of health psychology. Health psychology is a subfield of psychology that focuses on understanding the importance of psychological influences on health and illness, and how people respond when they become ill (Taylor, 1999). Health psychology emerged as a discipline in the 1970s, a time of increasing awareness of the role behavioural and lifestyle factors play in the development of illnesses and diseases (Straub, 2007). In addition to studying the connection between stress and illness, health psychologists investigate issues such as the reasons people make certain lifestyle choices, e.g., smoking or eating unhealthy food, despite knowing the potential adverse health implications of such behaviours.

Health psychologists also work on creating and testing ways to help people change unhealthy behaviours. A key part of their job is to figure out which groups of people are more likely to have health problems because of the way they think or act. For instance, they might study how stress affects different age groups, like young adults versus older adults. By understanding who gets more stressed and how it changes over time, health psychologists can identify which age group might be more at risk for health issues like high blood pressure or anxiety disorders.

Watch this video: The Upside of Stress (4.5 minutes)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sZtEwEIUIOc

“The Upside of Stress” video by BrainCraft is licensed under the Standard YouTube Licence.

Cannon and the Fight-or-Flight Response

Stress, a universal experience, has intrigued scientists for nearly a century. A key figure in this exploration is Walter Cannon, an American physiologist whose groundbreaking work in the early 20th century has significantly shaped our understanding of how the body reacts to stress. Cannon’s insights into the fight-or-flight response have provided a foundational understanding of the body’s physiological mechanisms when confronted with stress.

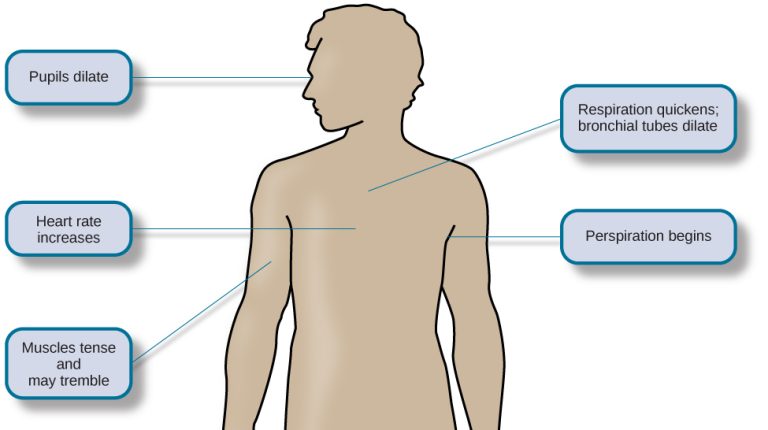

To illustrate Cannon’s fight-or-flight model, imagine you are back again, hiking in a forest when suddenly a large, barking dog appears. The dog, emerging from behind a stand of trees, stops about 50 yards from you. It notices you, barks louder, and starts moving in your direction. You think, “This is definitely not good,” and experience a series of physical reactions:

- Your pupils dilate.

- Your heart races and speeds up.

- You start breathing heavily and sweating.

- You feel butterflies in your stomach.

- Your muscles tense up, readying you to take action.

Cannon proposed that this reaction, termed the fight-or-flight response, occurs when a person experiences intense emotions, especially those associated with a perceived threat (Cannon, 1932). During the fight-or-flight response, the body is rapidly aroused by the activation of both the sympathetic nervous system and the endocrine system (Figure WB.5). This arousal prepares the person to either confront or escape the perceived threat.

In conclusion, Cannon’s concept of the fight-or-flight response has been instrumental in advancing our understanding of stress physiology. By identifying the body’s innate mechanism for maintaining homeostasis in the face of threats, Cannon’s work has laid the groundwork for further research into how we respond to stress. This response, crucial for survival, highlights the body’s remarkable ability to adapt to and manage challenging situations, a testament to the complex and dynamic nature of human physiology.

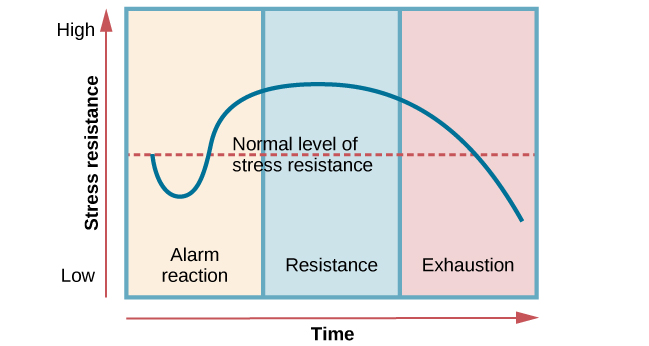

Having explored Cannon’s pivotal work on the immediate, fight-or-flight response to stress, we now turn to another seminal figure in stress research, Hans Selye. While Cannon focused on the body’s acute reaction to stress, Selye’s work delves into the prolonged effects of stress on the body. His concept of the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) offers a broader perspective, examining how our bodies cope with sustained stress over time. This shift from the immediate to the enduring effects of stress marks a significant development in our understanding of how stress impacts us.

Selye and the General Adaptation Syndrome

Content Disclosure: This section discusses historical research methods involving animal testing that are now considered unethical. These studies by Hans Selye were pivotal in stress research but raise important ethical concerns.

Selye initially focused on sex hormones in rats, but he incidentally discovered that prolonged exposure to stressors — such as extreme cold, surgical injury, and excessive muscular exercise — led to adrenal enlargement, thymus and lymph node shrinkage, and stomach ulceration in the rats. Selye realised that these health issues were part of a set of body reactions that occur over time under stress, regardless of the stressor’s nature. He termed this the general adaptation syndrome, a universal response of the body to stress.

It is important to note that Selye’s experiments, while groundbreaking, involved methods that would not meet current ethical standards. The distress and harm inflicted on the rats in his labs raises significant ethical concerns. Additionally, the extrapolation of these findings to human populations should be approached with caution.

In summary, Selye’s general adaptation syndrome model illustrates how our bodies may respond to stress in stages: initially with a burst of energy, then adapting, and finally, potentially breaking down if the stress continues for too long.

Life Changes as Stressors

Life changes, whether perceived as positive or negative, can act as significant stressors. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS), developed by Holmes and Rahe in 1967, highlights how events like marriage, divorce, job loss, or moving to a new home require an individual to make substantial adjustments, thereby inducing stress. These life changes are assigned “life change units” (LCUs) to quantify their potential impact on a person’s health. Interestingly, the scale suggests that not only negative events but also positive ones, such as promotions or the birth of a child, can produce stress due to the changes they bring to one’s life.

| Life event | Life change units |

|---|---|

| Death of a close family member | 63 |

| Personal injury or illness | 53 |

| Dismissal from work | 47 |

| Change in financial state | 38 |

| Change to different line of work | 36 |

| Outstanding personal achievement | 28 |

| Beginning or ending school | 26 |

| Change in living conditions | 25 |

| Change in working hours or conditions | 20 |

| Change in residence | 20 |

| Change in schools | 20 |

| Change in social activities | 18 |

| Change in sleeping habits | 16 |

| Change in eating habits | 15 |

| Minor violation of the law | 11 |

Table adapted from Holmes and Rahe (1967). The higher the number the more stressful the event.

The Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) provides researchers a simple, easy-to-administer way of assessing the amount of stress in people’s lives, and it has been used in hundreds of studies (Thoits, 2010). Despite its widespread use, the scale has been subject to criticism.

Understanding that life changes can be stressful regardless of their nature underscores the importance of developing coping mechanisms and support systems. It also highlights the subjective nature of stress, as individuals may perceive and react to the same event differently based on their personal resources, past experiences, and social support networks. Recognising and addressing the stress associated with life changes is crucial for maintaining mental health and well-being. This awareness can empower individuals to seek help when needed and to approach life’s transitions with strategies that promote resilience and adaptation.