Happiness & Positive Psychology

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

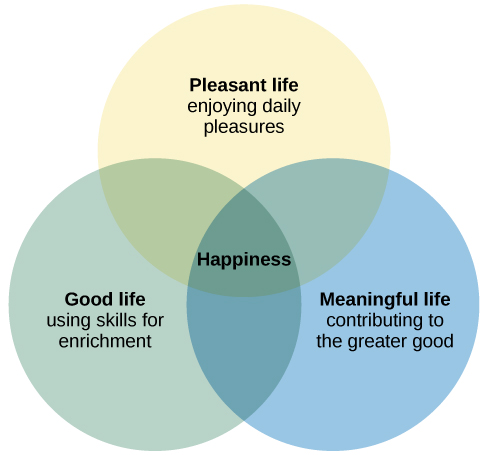

Elements of Happiness

Psychologists say happiness has three parts: the pleasant life, the good life, and the meaningful life (Seligman, 2002; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005). The pleasant life is about enjoying everyday pleasures that bring fun and excitement, like beach walks or a satisfying love life. The good life happens when we use our unique skills and get really into our work or hobbies. The meaningful life comes from using our talents for a greater cause, like helping others or improving the world. Generally, the happiest people focus on all three parts (Seligman et al., 2005).

To put it simply, happiness is a lasting feeling of joy, contentment, and the sense that your life is valuable (Lyubomirsky, 2001). It’s more than just feeling good temporarily; it’s about feeling good in the long run, known as subjective well-being.

Can We Make Ourselves Get Happier?

Some studies show that we can actually change our happiness levels for the better. For example, well-designed happiness programs can help people feel happier for a long time, not just for a moment. These programs can work for individuals, groups, or whole societies (Diener et al., 2006). One study found that simple activities like writing down three good things each day made people happier for over six months (Seligman et al., 2005).

If we measure happiness across societies, it can tell policy makers whether or not people are happy, and why. Research shows that a country’s average level of happiness is linked to six things: the country’s wealth (GDP), support from others, choices in how to live one’s life, a long, healthy life, government and businesses that people trust, and personal generosity (Helliwell et al., 2025). Understanding why people are happy or not can help governments create programs to make their societies happier (Diener et al., 2006). Decisions about important issues like poverty, taxes, healthcare, housing, clean environment, and income differences should consider how they will affect people’s happiness.

It’s important to know that we’re not always great at predicting our future emotions, a concept called affective forecasting (Wilson & Gilbert, 2003). For instance, most newlyweds think they’ll stay as happy as they are or become even happier, but a study found that their happiness actually went down over four years (Lavner, Karner, & Bradbury, 2013). We also often guess wrong about how big life events will change our happiness. For example, we might think winning the lottery or dating a famous person would make us forever happy, or that we’d be forever sad if we had a bad accident or a breakup.

But, just as our senses adjust to new situations (like our eyes getting used to bright light after exiting from a dark movie theatre), our emotions adjust to big changes in our lives (Brickman & Campbell, 1971; Helson, 1964). Initially, something good or bad can make us feel very happy or very sad. But over time, we get used to these changes, and our happiness level often goes back to what it was before. So, even exciting events like winning the lottery or your favourite team winning a big game eventually become normal (Brickman, Coats, & Janoff-Bulman, 1978). This is called hedonic adaptation. Those who are more resilient are able to bounce back and feel positive emotions even as they are experiencing stress (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004).

Positive Psychology

Positive psychology, pioneered by Seligman in 1998, represents a significant shift in the focus of psychological research and practice. Unlike traditional psychology, which often centres on addressing mental illness and emotional difficulties, positive psychology aims to enhance the well-being and flourishing of individuals by understanding and promoting enduring aspects of human experience that contribute to a fulfilling life (Compton, 2005). This field explores valuable experiences like well-being, contentment and happiness. Positive Psychology also examines positive traits, such as the ability to love, have courage, be creative, develop wisdom, be kind, forgive, show positive emotions, improve immune system health, develop character virtues and enjoy life. (Compton, 2005).

The scope of positive psychology includes research areas like altruism (being of service to others), empathy, creativity, and the impact of positive emotions on immune system functioning, as well as how savouring life’s moments and developing virtues contribute to authentic happiness. Positive Psychology also focuses on how to resolve conflict and foster peace and well-being at the community and global level (Cohrs, Christie, White, & Das, 2013).

PERMA Model + Flow

Seligman’s PERMA model is a way to understand what makes life most fulfilling and happy. “PERMA” stands for Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment. These five aspects plus Flow (when you’re really into something you’re doing, so much that you forget about time and everything else around you) are key ingredients for a good life, according to positive psychology, a branch of psychology that focuses on what makes life worth living.

- Positive Emotions: Feeling good and experiencing joy, gratitude, optimism, and other positive feelings that uplift us.

- Engagement: Being deeply involved and absorbed in activities that challenge and utilize our skills and interests.

- Relationships: Building strong, supportive connections with others that bring love, belonging, and social support.

- Meaning: Finding a sense of purpose and understanding that we are part of something bigger than ourselves.

- Accomplishment: Pursuing goals, overcoming challenges, and achieving success that contributes to a sense of fulfillment and pride.

Both flow and engagement help us feel more connected to what we are doing and give us a sense of satisfaction. They are crucial for our well-being because they make us feel alive and part of something bigger. When we experience flow and engagement, we are using our strengths and abilities to their fullest, which is a key part of being happy and fulfilled.

Rewiring for Happiness: Overcoming the Brain’s Negativity Bias

Understanding how to rewire our brains for happiness involves recognising a concept known as the negativity bias. This term refers to our brain’s tendency to give more attention and weight to negative experiences than to positive ones (Hanson & Mendius, 2009; Rozin & Royzman, 2001). This bias isn’t merely a result of our genetic makeup; it’s also shaped by our experiences throughout life. It manifests in various ways, including our stronger reactions to negative events and our tendency to recall unpleasant experiences more vividly than pleasant ones (Monterrubio, Andriotis, & Rodríguez-Muñoz, 2020; Everly Jr. & Lating, 2019).

While our negativity bias has roots in our evolutionary past — serving as a survival mechanism by making us more alert to potential threats — its usefulness extends into modern life. Our negativity bias can prompt us to evaluate risks carefully and make decisions that protect us from harm. This cautious approach can be beneficial in complex social situations and professional environments, where anticipating challenges and preparing for possible mistakes or complications can lead to better outcomes.

However, the harms caused by our negativity bias are significant and can affect various aspects of our lives. Overemphasis on negative experiences can cause us to experience chronic stress, anxiety, and depression. It can distort our perceptions, making us more likely to see threats where none exist and undervalue positive aspects of our lives. This skewed perspective can hinder our personal growth, strain our relationships, and reduce our overall life satisfaction. Furthermore, in professional settings, a strong negativity bias might stifle creativity and innovation, as the fear of failure or criticism can prevent us from taking the necessary creative risks.

It’s crucial for us to balance our in born negativity bias with a conscious effort to acknowledge and savour positive experiences. By doing so, we can lessen the impact of negativity bias on our mental health and overall well-being. Developing a more balanced perspective allows us to enjoy a fuller, more satisfying life in which we’re not focused just on avoiding the bad but also embracing the good. By actively working to balance our perspective, we can mitigate these negative effects. This involves practices such as mindfulness, gratitude journaling, and positive reframing, which help us to notice and appreciate the positive aspects of our experiences. Over time, these practices can help rewire our brains to become more attuned to positivity, fostering a healthier, more resilient mindset.

The “Pursuit” of Happiness?

The term “pursuit of happiness” describes how some people with individualistic values think about happiness. They can often believe that happiness is something they need to chase after or work hard to get. They think being free, showing who they really are, and achieving their goals will make them happy. But this idea also means that happiness is something you have to chase, and you might not always catch it.

In other parts of the world, like Asia, Africa, and Latin America, and in Indigenous cultures, people see happiness differently. For these collectivistic cultures, happiness isn’t really about chasing after things. Instead, it’s about how people feel about their life as it is. They find happiness in living in the moment and being part of their community. It’s not about doing specific things to be happy; it’s more about feeling content with where you are and who you’re with.