Focused Perspectives on Lifespan Development

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Doll Experiment

Mamie and Kenneth Clark’s doll experiment in the 1940s made a pivotal contribution to our understanding of lifespan development, particularly in the context of racial bias and its influence on self-perception from an early age. This experiment was designed to explore the psychological impact of segregation on African-American children by presenting them with two dolls, identical except for their skin and hair colour, and asking the children to choose based on preference and the attribution of positive traits. The majority of children — both Black and white — preferred the white doll, associating it with positive characteristics. This preference indicated an early internalisation (inner sense of self) of racial bias and a negative self-perception among Black children, influenced by societal norms of racial discrimination.

The findings from this experiment underscore the profound effect of societal factors, like discrimination, on a child’s self-esteem and self-image, illustrating how early experiences of bias can impact development and mental health throughout life. The Clarks’ work emphasised the importance of the early environment in shaping an individual’s development, highlighting the need for societal changes to address these biases.

Their study significantly influenced the Brown versus Board of Education Supreme Court case in 1954, which led to school desegregation in the US. It underscored the importance of inclusive environments for positive child development and influenced educational policies and environments for future generations.

The Clarks’ experiment revealed the impact of societal factors on self and others’ perception, informing interventions to support healthy development across the lifespan.

https://youtu.be/BceFXfC1aG4?si=D6W7YZ_R93wKkgBU

Vygotsky and the Sociocultural Construction of Cognition

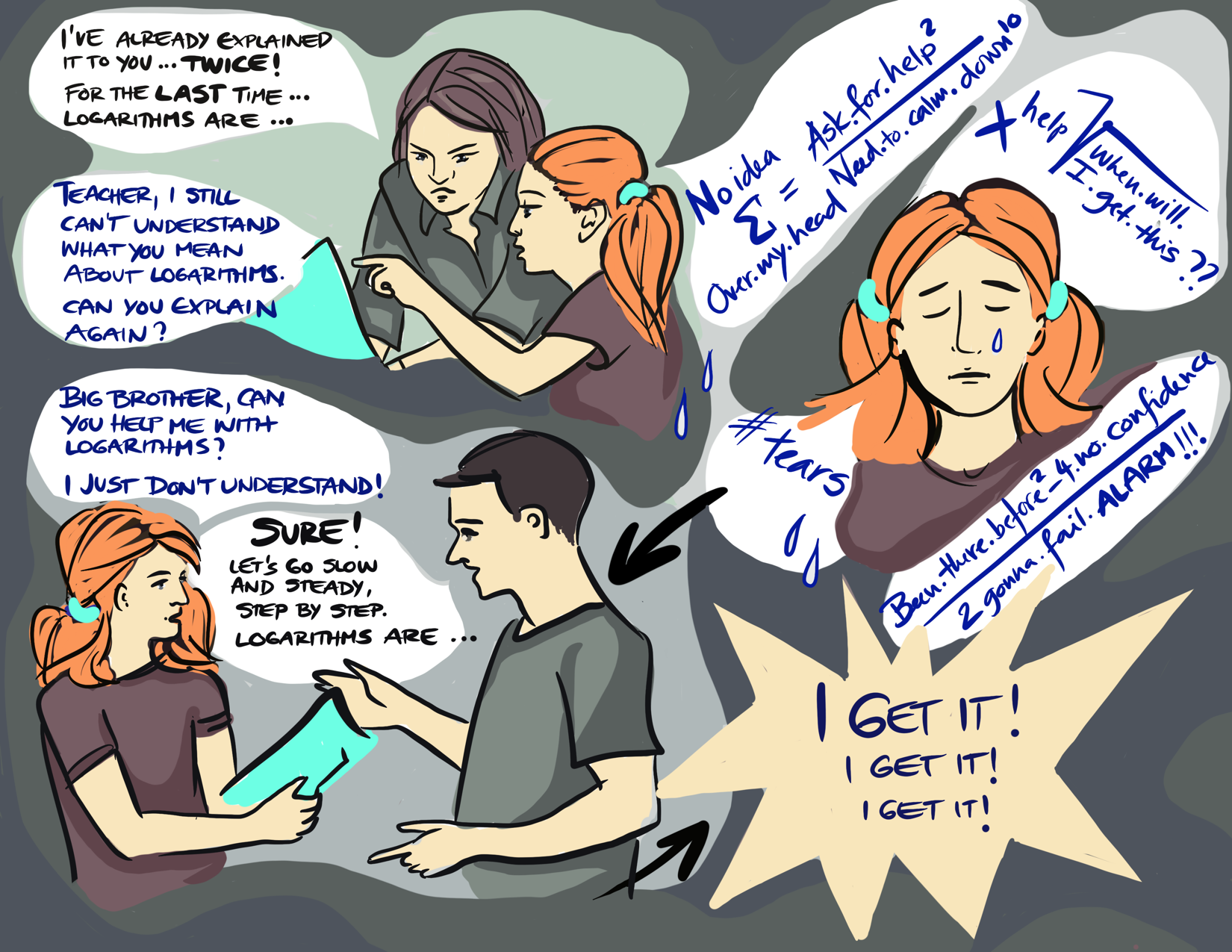

Lev Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of development emphasises the significant role of culture and social interactions in shaping cognitive development. Central to his theory are three distinct zones that describe the steps of learning and development, which can be simplified to: “What I Cannot Do Yet”, “What I Can Do With Help (Zone of Proximal Development)”, and “What I Can Do By Myself (Zone of Achieved Development)”. Let’s look at each step.

Prior to entering the Zone of Development (What I Cannot Do Yet) there are tasks and concepts that lie beyond an individual’s current capabilities and understanding. These represent areas of future learning and growth, highlighting the potential for development as foundational skills are strengthened and more complex tasks are approached.

Zone of Proximal Development (What I Can Do With Help) is the core of Vygotsky’s theory. This zone defines the difference between what a learner can achieve independently and what they can accomplish with guidance and encouragement from someone more knowledgeable, such as a teacher, parent, or peer. It’s in this zone that the concept of scaffolding plays a crucial role. Scaffolding involves step by step, customized support provided by the more knowledgeable other, which is gradually withdrawn as the learner gains independence. Tasks within the zone of proximal development are slightly beyond the learner’s current reach but are attainable with the appropriate support, facilitating significant learning and cognitive development.

Zone of Achieved Development (What I Can Do By Myself) encompasses the tasks and concepts an individual can perform or understand without any external assistance. This zone reflects the learner’s current level of independent competence, showcasing the skills and knowledge they have already mastered. It serves as the foundation for future learning, as the skills acquired independently become the basis for tackling more challenging tasks within the Zone of Proximal Development.

By identifying these three learning zones, Vygotsky highlights how important mentors, Elders, and knowledgeable peers are to our ability to learn and grow. Through this framework, Vygotsky provides a comprehensive model for understanding how individuals progress from potential development to actualised skills and knowledge.

Psychosocial Development: Erikson

Erik Erikson’s (1902–1994) psychosocial development theory emphasises the social nature of our development. Erikson (1963) proposed that we are motivated by a need to achieve competence in certain areas of our lives. According to psychosocial theory, we experience eight stages of development over our lifespan, from infancy through late adulthood. At each stage, there is a conflict, or task, that we need to resolve. Successful completion of each developmental task results in a sense of competence and a healthy personality. Failure to master these tasks leads to feelings of inadequacy. Let’s look at Erikson’s eight stages of psychosocial development:

- Infancy (birth to 12 months): Trust versus mistrust is the core conflict, where responsive care fosters trust in infants while neglect leads to mistrust. Infants are dependent upon their caregivers, so caregivers who are responsive and sensitive to their infant’s needs help their baby to develop a sense of trust; their baby will see the world as a safe, predictable place. Unresponsive caregivers who do not meet their baby’s needs can engender feelings of anxiety, fear, and mistrust; their baby may see the world as unpredictable.

- Toddlerhood (1–3 years): The stage of autonomy versus shame and doubt, where toddlers learn independence through choices, enhancing autonomy; over-restriction fosters doubt. This is the “I do it” stage.

- Preschool (3–6 years): Initiative versus guilt, where children develop self-confidence and purpose through initiating activities; excessive criticism leads to guilt. Those who do will develop self-confidence and feel a sense of purpose.

- Elementary School (7–11 years): Industry versus inferiority, where children build pride and accomplishment through skills and activities; failure to match peers can cause feelings of inferiority. They either develop a sense of pride and accomplishment in their schoolwork, sports, social activities, and family life, or they feel inferior and inadequate when they don’t measure up.

- Adolescence (12–18 years): Identity versus role confusion, focusing on developing a strong sense of self; failure results in confusion about identity and future roles. Adolescents struggle with questions such as “Who am I?” and “What do I want to do with my life?” Along the way, most adolescents try on many different selves to see which ones fit. Adolescents who are successful at this stage have a strong sense of identity and are able to remain true to their beliefs and values in the face of problems and other people’s perspectives. Others might feel unsure of their identity and confused about the future.

- Early Adulthood (20s to early 40s): Intimacy versus isolation, where forming intimate relationships is key; failure leads to isolation. After we have developed a sense of self in adolescence, we are ready to share our life with others. Erikson said that we must have a strong sense of self before developing intimate relationships with others.

- Middle Adulthood (40s to mid-60s): Generativity versus stagnation, involving contributing to others’ development; failure results in a sense of stagnation. Generativity involves finding your life’s work and contributing to the development of others, through activities such as volunteering, mentoring, and raising children.

- Late Adulthood (mid-60s onward): Integrity versus despair, where reflecting on life achievements can lead to satisfaction; failure may result in regret and despair. People in late adulthood reflect on their lives and feel either a sense of satisfaction or a sense of failure. People who feel proud of their accomplishments have a sense of integrity, and they can look back on their lives with few regrets. However, people who are not successful at this stage may feel as if their lives have been wasted.

| Stage | Age (years) | Developmental Task | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0–1 | Trust versus mistrust | Develop trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met. |

| 2 | 1–3 | Autonomy versus shame/doubt | Develop a sense of independence in many tasks. |

| 3 | 3–6 | Initiative versus guilt | Take initiative on some activities; may develop guilt when unsuccessful or boundaries overstepped. |

| 4 | 7–11 | Industry versus inferiority | Develop self-confidence in abilities when competent or sense of inferiority when not. |

| 5 | 12–18 | Identity versus confusion | Experiment with and develop identity and roles. |

| 6 | 19–29 | Intimacy versus isolation | Establish intimacy and relationships with others. |

| 7 | 30–64 | Generativity versus stagnation | Contribute to society and be part of a family. |

| 8 | 65– | Integrity versus despair | Assess and make sense of life and meaning of contributions. |

Table Source: Erikson, E. H. (1950). Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. In Childhood and society (pp. 247-274). W. W. Norton & Company.

Stages of Cognitive Development: Piaget

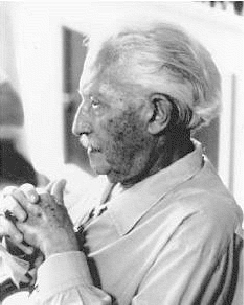

Jean Piaget (1896–1980) is another stage theorist who studied childhood development (Figure LD.7). Instead of approaching development from a psychosocial perspective, Piaget focused on children’s cognitive growth. He believed that thinking is a central aspect of development and that children are naturally inquisitive. However, he said that children do not think and reason like adults (Piaget, 1930, 1932). His theory of cognitive development suggests that our cognitive abilities develop through specific stages, which is an example of the discontinuity of development, i.e., as we progress to a new stage, there is a distinct and irreversible shift in how we think and reason.

Piaget said that children develop schemata to help them understand the world. Schemata are concepts (mental models) that are used to help us categorise and interpret information. By the time children have reached adulthood, they have created schemata for almost everything. When children learn new information, they adjust their schemata through two processes: assimilation and accommodation. First, they assimilate new information or experiences in terms of their current schemata: assimilation is when they take in information that is comparable to what they already know; accommodation describes when they change their schemata based on new information. This process continues as children interact with their environment.

For example, 2-year-old Majd learned the schema for dogs because his family has a Labrador Retriever. When Majd sees other dogs in his picture books, he says to his parents, “Dog!” So Majd has assimilated them into his schema for dogs. One day, Majd sees a sheep for the first time and says to his parent, “Dog!” Having a basic schema that a dog is an animal with four legs and fur, Majd thinks all furry, four-legged creatures are dogs. When Majd’s parent tells him that the animal he sees is a sheep, not a dog, Majd must accommodate his schema for dogs to include more information based on his new experiences. Majd’s schema for dog was too broad, since not all furry, four-legged creatures are dogs. He now modifies his schema for dogs and forms a new one for sheep.

Like Erikson, Piaget thought that development unfolds in a series of stages approximately associated with age ranges. He proposed a theory of cognitive development that unfolds in four stages: sensorimotor, pre-operational, concrete operational, and formal operational (Table LD.2).

| Age (years) | Stage | Description | Developmental issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2 | Sensorimotor | World experienced through senses and actions. | Object permanence; Stranger anxiety |

| 2–6 | Preoperational | Use words and images to represent things, but lack logical reasoning. | Pretend play; Egocentrism; Language development |

| 7–11 | Concrete operational | Understand concrete events and analogies logically; perform arithmetical operations | Conservation; Mathematical transformations |

| 12– | Formal operational | Formal operations; Utilise abstract reasoning |

Abstract logic; Moral reasoning |

Table source: Piaget, J. (2001). Piaget’s stages of cognitive development. In B. Inhelder, H. H. Chipman, & C. Zwingmann (Eds.), The essential Piaget (pp. 241-246). Basic Books.

Stage 1 – Sensorimotor Stage

The first stage is the sensorimotor stage, which lasts from birth to about 2 years old.

- During this stage, children learn about the world through their senses and motor behaviour.

- Young children put objects in their mouths to see if the items are edible, and once they can grasp objects, they may shake or bang them to see if they make sounds.

- Between 5 and 8 months old, the child develops object permanence, which is the understanding that even if something is out of sight, it still exists (Bogartz, Shinskey, & Schilling, 2000). According to Piaget, young infants do not remember an object after it has been removed from sight. Piaget studied infants’ reactions when a toy was first shown to an infant and then hidden under a blanket. Infants who had already developed object permanence would reach for the hidden toy, indicating that they knew it still existed, whereas infants who had not developed object permanence would appear confused.

In Piaget’s view, around the same time children develop object permanence, they also begin to exhibit stranger anxiety, which is a fear of unfamiliar people. Babies may demonstrate this by crying and turning away from a stranger, by clinging to a caregiver, or by attempting to reach their arms toward familiar faces such as parents. Stranger anxiety results when a child is unable to assimilate the stranger into an existing schema; therefore, the child can’t predict what their experience with that stranger will be like, which results in a fear response.

Stage 2 – Preoperational Stage

Piaget’s second stage is the preoperational stage, which is from approximately 2 to 7 years old. In this stage, children can:

- Use symbols to represent words, images, and ideas, which is why children in this stage engage in pretend play.

- Use language in the preoperational stage, but they cannot understand adult logic or mentally manipulate information (the term operational refers to logical manipulation of information, so children at this stage are considered to be preoperational). Children’s logic is based on their own personal knowledge of the world so far, rather than on conventional knowledge.

- Cannot perform mental operations because they have not developed an understanding of conservation, which is the idea that even if you change the appearance of something, it is still equal in size as long as nothing has been removed or added.

Stage 3 – Concrete Operational Stage

Piaget’s third stage is the concrete operational stage, which occurs from about 7 to 11 years old. In this stage, children can:

- Think logically about real (concrete) events; they have a firm grasp on the use of numbers and start to employ memory strategies;

- Perform mathematical operations and understand transformations, such as the fact that addition is the opposite of subtraction, and multiplication is the opposite of division; and

- Master the concept of conservation: even if something changes shape, its mass, volume, and number stay the same.

Children in the concrete operational stage also understand the principle of reversibility, which means that objects can be changed and then returned back to their original form or condition. Take, for example, water that you poured into the short, wide glass; you can pour that same volume of water from the short, wide glass into a new thin, tall glass and still have the same amount (minus a couple of drops).

Stage 4 – Formal Operational Stage

The fourth, and last, stage in Piaget’s theory is the formal operational stage, which is from about age 11 to adulthood. Children in the formal operational stage can:

- Deal with abstract ideas and hypothetical situations; this is because they tend to think more flexibly and creatively;

- Use abstract thinking to problem-solve, look at alternative solutions, and test these solutions.

Stage 5 – Beyond Formal Operational Thought

As with other major contributors of theories of development, several of Piaget’s ideas have come under criticism; several contemporary studies support a model of development that is more continuous than Piaget’s discrete stages (Courage & Howe, 2002; Siegler, 2005, 2006). Many others suggest that children reach cognitive milestones earlier than Piaget describes (Baillargeon, 2004; de Hevia & Spelke, 2010).

According to Piaget, the highest level of cognitive development is formal operational thought, which develops between 11 and 20 years old. However, many developmental psychologists disagree with Piaget, suggesting a fifth stage of cognitive development, known as the postformal stage (Basseches, 1984; Commons & Bresette, 2006; Sinnott, 1998).

In postformal thinking, decisions are made based on situations and circumstances, and logic is integrated with emotion as adults develop principles that depend on contexts. One way that we can see the difference between an adult in postformal thought and an adolescent in formal operations is in terms of how they handle emotionally charged issues.

Watch this video: Tricky Topics: Piaget’s Developmental Stages (9 minutes)

“Tricky Topics: Piaget’s Developmental Stages” video by FirstYearPsych Dalhousie is licensed under the Standard YouTube Licence.

Moral Development: Kohlberg and Gilligan

Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

A major task, beginning in childhood and continuing into adolescence, is distinguishing right from wrong. Lawrence Kohlberg (1927–1987) attempted to extend Piaget’s ideas about stages of cognitive development to moral development, suggesting that morality, too, was developed over a series of stages throughout life. To develop this theory, Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas to people of all ages and placed them in particular stages based upon analysis of their answers.

Kohlberg divided moral development into three main levels: pre-conventional, conventional, and post-conventional, each reflecting a different way of thinking about morals and ethics.

Watch this video: Kohlberg’s 6 Stages of Moral Development (7 minutes)

“Kohlberg’s 6 Stages of Moral Development” video by Sprouts is licensed under the Standard YouTube Licence.

Pre-conventional level

At the pre-conventional level, there is an understanding of morality based on consequences and personal benefits. This is the initial stage of moral development, primarily seen in children.

- Stage 1: Obedience and punishment orientation (“Do right to avoid trouble”). At this stage, children see rules as fixed and absolute. They obey rules not because they understand them, but because they fear punishment. For example, a child may refrain from stealing a toy because they fear being reprimanded or punished.

- Stage 2: Individualism and exchange (“What’s in it for me?”). Here, children realise that different individuals have different viewpoints. They start to consider what’s in it for them. Rules are followed if they align with their immediate personal interest. For instance, a child might do a chore in exchange for a reward.

Conventional level

At the conventional level, moral decisions are based on societal norms (staying within social and cultural conventions) and the desire to maintain order and good relationships. This level is typical in adolescence and adulthood.

- Stage 3: Good interpersonal relationships (“Be a good person”). At this stage, people strive for social approval and good relationships. They try to be “good” by living up to social expectations and roles. For example, a worker might go the extra mile on a task not because they think it’s right, but because they want to be seen as a good employee.

- Stage 4: Maintaining the social order (“Law and order”). People start to consider society as a whole. They recognise the importance of obeying laws and respect authority for maintaining social order. An example is a citizen paying taxes not just because it’s the law, but because they understand the role of taxes in societal functioning.

Post-conventional level

At the post-conventional level, there is a questioning of authority and societal norms (going beyond social and cultural conventions) and decisions based on personal principles of justice and human rights.

- Stage 5: Social contract and individual rights (“Questioning authority”). Here, people understand that while rules and laws exist for the good of the majority, there are times when those laws can work against the rights of some individuals. They begin to account for different values, opinions, and beliefs. For instance, someone may support civil disobedience to challenge laws they see as unjust.

- Stage 6: Universal principles (“Moral compass”). At this stage, people have developed their own set of moral guidelines which may or may not align with societal laws. These principles are abstract and ethical, not concrete rules. They’re upheld regardless of official rules and laws and applied universally. An example might be a person who believes in and practices non-violence, even when it’s legally permissible or advantageous to be violent.

It’s important to note that Kohlberg believed individuals could only progress through these stages in the order listed, and that moral understanding is linked to cognitive development. However, not everyone reaches the post-conventional level; some people stop at earlier stages and spend their whole lives there. Critics have argued that Kohlberg’s stages are overly focused on justice and don’t sufficiently incorporate other important moral values, such as compassion and care.

| Level | Stage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Conventional | 1: Obedience and Punishment Orientation | Children see rules as fixed and absolute, obeying to avoid punishment. |

| Pre-Conventional | 2: Individualism and Exchange | Children start to see that different individuals have different viewpoints, following rules if it aligns with their interests. |

| Conventional | 3: Good Interpersonal Relationships | People strive for social approval and good relationships, trying to be ‘good’ by living up to expectations. |

| Conventional | 4: Maintaining the Social Order | People consider society as a whole, recognising the importance of laws and authority for social order. |

| Post-Conventional | 5: Social Contract and Individual Rights | People understand that laws exist for the majority’s good, but can challenge them if they infringe on individual rights. |

| Post-Conventional | 6: Universal Principles | People follow their own set of moral guidelines, which may not align with societal laws, based on universal principles. |

Carol Gilligan and the Ethic of Care

Using this framework, Kohlberg erroneously claimed that more males than females reach higher stages and that females seem to be deficient in their moral reasoning abilities (1969). Carol Gilligan, who worked with Kohlberg, challenged his framework (Gilligan, 1982). Kohlberg studied predominantly upper-middle class, white males and Gilligan pointed out the obvious bias inherent in basing a theory on such a narrowly defined group of people. Using female participants, she redefined Kohlberg’s stages to allow moral problems to be considered from different perspectives.

Although an improvement over Kohlberg’s theories, the dilemma-based tasks used by Gilligan assessed moral reasoning, which is different from moral behaviour. Sometimes what we say we’d do in a situation (“talk the talk”) is not what we actually do (“walk the walk”). So, how exactly does one define moral behaviour? The definition of what makes a “good person” has long been the subject of philosophical debate and is unlikely to reach consensus anytime soon. As a tool for measuring moral development, neither Kohlberg’s nor Gilligan’s dilemmas are feasible in young children, who do not have the language comprehension required for these tests. In fact, Kohlberg lumped all children under the age of 10 in the same level of moral development.

A more evidence-based approach is to measure specific components of morality which are easier to define, like prosocial behaviour, defined as any behaviour done with the intention of benefiting someone else. This includes acts such as helping, consoling, and sharing, and can be assessed using simple behavioural tests. For example, participants can be asked to allocate resources to themselves and others under different conditions. Research using these simpler tasks has revealed that helping behaviour and sharing are evident in children as young as 2 years old, and that the nature of these prosocial behaviours changes over the course of development (Warneken & Tomasello, 2006; Williams et al., 2014).

One 2019 study compared rates at which infants demonstrated prosocial behaviours (i.e., caring for others) across a range of three different ages: 16-, 19-, and 24-months-old. To do this, infants were placed in a situation where a researcher, using verbal communication and body language, indicated that they needed help with a basic task, such as finding a hidden toy. They then recorded the infants’ prosocial behaviour according to three different categories: instrumental helping (such as offering the researcher a different object), comforting (such as hugging the upset researcher), and indirect helping (such as asking another adult in the room for help). The study found that the 24-month old children were significantly more likely to demonstrate prosocial behaviours than the 16- and 19-month-olds, particularly when it came to comforting. This suggests that the second year of life is an extremely important period in the development of this important component of morality (Holvoet, et al. 2019).

This approach remedies some of the problems with Kohlberg’s studies, in that he didn’t define specific “good” or “bad” behaviours. Rather he assumed that his own ideas about good versus bad behaviour were true, and incorporated these assumptions into the design of his studies. Therefore, the outcomes of Kohlberg’s studies were strongly influenced by his culturally-informed ideas about morality. Instead focusing on one aspect of morality, like prosocial behaviour (described above), it allows researchers to assess developmental changes without judging this aspect as morally good or bad. This approach also ensures that judgements about what constitutes “good” behaviour doesn’t colour the scientific data being collected or the design of the studies being done.

Conclusion

In concluding our look at “Focused Perspectives on Lifespan Development,” we’ve examined a range of theories and concepts that enhance our understanding of human development. We’ve discussed intersectionality, power, and diverse viewpoints, along with Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory and the impact of technology on young people. This section highlighted various factors that shape development.

Each topic has shown how individuals interact with their surroundings, emphasising the role of context, culture, and social dynamics in development. Through various analyses, we’ve observed how both challenges and opportunities enrich human development across the lifespan.

Moving forward, we recognise development as a multifaceted process, shaped by social, cultural, and psychological factors. This section has provided the tools to critically understand and appreciate human development’s complexity, promoting a comprehensive and inclusive view of the developmental journey from infancy to adulthood.