Ages, Stages, and Milestones of Development

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Infancy Through Childhood

The average newborn weighs approximately 7.5 pounds. Although small, a newborn is not completely helpless because their reflexes and sensory capacities help them interact with the environment from the moment of birth. All healthy babies are born with newborn reflexes: inborn automatic responses to specific forms of stimulation. Reflexes help the newborn survive until they’re capable of more complex behaviours; these reflexes are crucial to survival. They are present in babies whose brains are developing normally and usually disappear around 4–5 months old.

Let’s Take a Look at Some of These Newborn Reflexes

The rooting reflex is the newborn’s response to anything that touches their cheek; when you stroke a baby’s cheek, they naturally turn their head in that direction and begin to suck. The sucking reflex is the automatic, unlearned, sucking motions that infants do with their mouths. You can observe the grasping reflex if you put your finger into a newborn’s hand, they automatically grasp anything that touches their palms.

The Moro reflex is the newborn’s response when a baby feels like they are falling. The baby spreads their arms, pulls them back in, and then (usually) cries. How do you think these reflexes promote survival in the first months of life?

Watch this video, created by the Inter-Tribal Council of Michigan, describing and showing newborn reflexes, to learn more.

Watch this video: Newborn Reflexes: The Power of Your Newborn (5 minutes)

“Newborn Reflexes: The Power of Your Newborn” video by Inter-Tribal Council of Michigan is licensed under the Standard YouTube Licence.

What Can Young Infants See, Hear, and Smell?

Newborn infants’ sensory abilities are significant, but their senses are not yet fully developed. Many of a newborn’s innate preferences facilitate interaction with caregivers and other humans. Although vision is their least developed sense, newborns already show a preference for faces. Babies who are just a few days old also prefer human voices; they will listen to voices longer than sounds that do not involve speech (Vouloumanos & Werker, 2004). They seem to prefer the voice of the parent in whose womb the baby developed over a stranger’s voice (Mills & Melhuish, 1974). 3-week-old babies were given pacifiers that played a recording of the pregnant parent’s voice and of a stranger’s voice. When the infants heard their parent’s voice, they sucked more strongly at the pacifier (Mills & Melhuish, 1974).

Newborns also have a strong sense of smell. Newborn babies can distinguish the smell of the parent who was pregnant from that of others. 1-week-old babies who were being breastfed were placed between two gauze pads. One gauze pad was from the bra of a nursing parent who was a stranger, and the other gauze pad was from the bra of the infant’s own nursing parent. More than two-thirds of the week-old babies turned toward the gauze pad with their own nursing parent’s scent (MacFarlane (1978).

Physical Development

During infancy, toddlerhood, and early childhood, the body’s physical development is rapid. On average, newborns weigh between 5 and 10 pounds. By the age of 2, this weight will have quadrupled, with most 2-year-olds weighing between 20 and 40 pounds (WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006). Growth slows between 4 and 6 years old. During this time children gain 5–7 pounds and grow about 2–3 inches per year.

The nervous system continues to grow and develop after birth; each neural pathway forms thousands of new connections during infancy and toddlerhood. This period of rapid neural growth is called blooming. The blooming period of neural growth is then followed by a period of pruning, where neural connections are reduced. It is thought that pruning allows the brain to function more efficiently, allowing for mastery of more complex skills (Hutchinson, 2011). Blooming occurs during the first few years of life, and pruning continues through childhood and into adolescence in various areas of the brain.

The size of our brains increases rapidly.

- The brain of a 2-year-old is 55% of its adult size, and by the age of 6 the brain is about 90% of its adult size (Tanner, 1978).

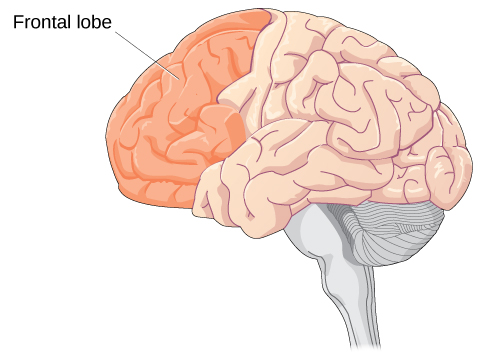

- During early childhood (ages 3–6), the frontal lobes grow rapidly. The frontal lobes are associated with planning, reasoning, memory, and impulse control.

- Through the elementary school years, the frontal, temporal, occipital, and parietal lobes all grow in size.

- The brain growth spurts experienced in childhood tend to follow Piaget’s sequence of cognitive development, so that significant changes in neural functioning are associated with cognitive advances (Kolb & Whishaw, 2009; Overman, Bachevalier, Turner, & Peuster, 1992).

Movement

Motor development occurs in an orderly sequence as infants move from reflexive reactions (e.g., sucking and rooting) to more advanced motor functioning.

Motor skills refer to our ability to move our bodies and manipulate objects. Fine motor skills focus on the muscles in our fingers, toes, and eyes, and enable coordination of small actions (e.g., grasping a toy, writing with a pencil, and using a spoon). Gross motor skills focus on large muscle groups that control our arms and legs and involve larger movements (e.g., balancing, running, and jumping). As motor skills develop, there are certain developmental milestones that young children typically achieve at certain age ranges (Table LD.5). An example of a developmental milestone is sitting. On average, most babies sit alone at 7 months old. Sitting involves both coordination and muscle strength, and 90 percent of babies achieve this milestone between 5 and 9 months old. Babies on average are able to hold up their head at 6 weeks old, and 90 percent of babies achieve this between 3 weeks and 4 months old.

Caregivers should be concerned about a child who is displaying delays on several milestones, since some developmental delays can be identified and addressed through early intervention.

| Age (years) | Physical | Personal/Social | Language | Cognitive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Kicks a ball; walks up and down stairs | Plays alongside other children; copies adults | Points to objects when named; puts 2–4 words together in a sentence | Sorts shapes and colours; follows 2-step instructions |

| 3 | Climbs and runs; pedals tricycle | Takes turns; expresses many emotions; dresses self | Names familiar things; uses pronouns | Plays make believe; works toys with parts (levers, handles) |

| 4 | Catches balls; uses scissors | Prefers social play to solo play; knows likes and interests | Knows songs and rhymes by memory | Names colours and numbers; begins writing letters |

| 5 | Hops and swings; uses fork and spoon | Distinguishes real from pretend; likes to please friends | Speaks clearly; uses full sentences | Counts to 10 or higher; prints some letters and copies basic shapes |

Cognitive Development

In addition to rapid physical growth, young children also exhibit significant development of their cognitive abilities. Piaget thought that a child’s ability to understand objects, such as learning that a rattle makes a noise when shaken, is a cognitive skill that develops slowly as a child matures and interacts with the environment.

Today, developmental psychologists think Piaget was incorrect about that. Researchers have found that even very young children understand physical properties of objects long before they have direct experience with those objects (Baillargeon, 1987; Baillargeon, Li, Gertner, & Wu, 2011). For example, children as young as 3 months old demonstrated knowledge of the properties of objects that they had only viewed and did not have prior experience with them.

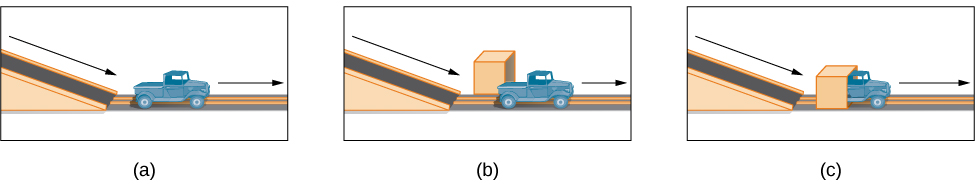

In one study, 3-month-old infants were shown a truck rolling down a track and behind a screen. The box, which appeared solid but was actually hollow, was placed next to the track. The truck rolled past the box as would be expected. Then the box was placed on the track to block the path of the truck. When the truck was rolled down the track this time, it continued unimpeded. The infants spent significantly more time looking at this impossible event (Figure LD.11). Baillargeon (1987) concluded that the infants knew that solid objects cannot pass through each other.

Baillargeon’s findings suggest that very young children have an understanding of objects and how they work, which Piaget (1954) would have said is beyond their cognitive abilities due to their limited experiences in the world.

Like physical milestones, there are also cognitive milestones children typically reach at certain ages. For example, infants shake their head “no” around 6–9 months, and they respond to verbal requests to do things like “wave bye-bye” or “blow a kiss” around 9–12 months. Remember Piaget’s ideas about object permanence? We can expect children to grasp the concept that objects continue to exist even when they are not in sight by around 8 months old. Because toddlers (i.e., 12–24 months old) have mastered object permanence, they enjoy games like hide and seek, and they realise that when someone leaves the room they will come back (Loop, 2013). Toddlers also point to pictures in books and look in appropriate places when you ask them to find objects.

Preschool-age children (i.e., 3–5 years old) also make steady progress in cognitive development. Not only can they count, name colours, and tell you their name and age, but they can also make some decisions on their own, such as choosing an outfit to wear. Preschool-age children understand basic time concepts and sequencing (e.g., before and after), and they can predict what will happen next in a story. They also begin to enjoy the use of humour in stories. Because they can think symbolically, they enjoy pretend play and inventing elaborate characters and scenarios. One of the most common examples of their cognitive growth is their blossoming curiosity. Preschool-age children love to ask “Why?”

An important cognitive change occurs in children this age. Recall that Piaget described 2–3 year olds as egocentric, meaning that they do not have an awareness of others’ points of view. Between 3 and 5 years old, children come to understand that people have thoughts, feelings, and beliefs that are different from their own. This is known as theory-of-mind (TOM). Children can use this skill to tease others, persuade their parents to purchase a candy bar, or understand why a sibling might be angry. When children develop TOM, they can recognise that others have false beliefs (Dennett, 1987; Callaghan et al., 2005).

Watch this video outlining the basics of Theory of Mind and showing young children engaging in a classic ‘false belief’ or ToM activity – the ‘Sally-Anne’ test.

Watch this video: Theory of Mind (4 minutes)

“Theory of Mind” video by BrainFacts.org is licensed under the Standard YouTube Licence.

Cognitive skills continue to expand in middle and late childhood (6–11 years old):

- The child’s thought processes become more logical and organised when dealing with concrete information.

- The child understands concepts such as the past, present, and future, giving them the ability to plan and work toward goals.

- The child can process complex ideas such as addition and subtraction and cause-and-effect relationships.

Language Development

One well-researched aspect of cognitive development is language acquisition. The order in which children learn language structures is consistent across children and cultures (Hatch, 1983).

- Starting before birth, babies begin to develop language and communication skills.

- At birth, babies apparently recognise the voice of their birth parent, and can discriminate between the language(s) spoken by their birth parent and foreign languages, and they show preferences for faces that are moving in synchrony with audible language (Blossom & Morgan, 2006; Pickens, 1994; Spelke & Cortelyou, 1981).

- Children communicate information through gesturing long before they speak, and there is some evidence that gesture usage predicts subsequent language development (Iverson & Goldin-Meadow, 2005).

- Babies begin to coo almost immediately. Cooing is a one-syllable combination of a consonant and a vowel sound (e.g., coo or ba).

- Babies replicate sounds from their own languages. A baby whose parents speak French will coo in a different tone than a baby whose parents speak Spanish or Urdu.

After cooing, the baby starts to babble. Babbling begins with repeating a syllable, such as ma-ma, da-da, or ba-ba.

- When a baby is about 12 months old, we expect them to say their first word for meaning, and to start combining words for meaning at about 18 months.

- At about 2 years old, a toddler uses between 50 and 200 words; by 3 years old they have a vocabulary of up to 1,000 words and can speak in sentences.

During the early childhood years, children’s vocabulary increases at a rapid pace. This is sometimes referred to as the “vocabulary spurt” and has been claimed to involve an expansion in vocabulary at a rate of 10–20 new words per week.

- Recent research may indicate that while some children experience these spurts, it is far from universal (as discussed in Ganger & Brent, 2004).

- 5-year-olds understand about 6,000 words, speak 2,000 words, and can define words and question their meanings. They can rhyme and name the days of the week.

- Seven-year-olds speak fluently and use slang and clichés (Stork & Widdowson, 1974).

You can read more about the development of language in the Intelligence and Language chapter.

Attachment

Psychosocial development happens as children build relationships, interact with others, and learn to handle their emotions. A key part of social and emotional growth is forming strong attachments, especially in infancy. Attachment refers to a deep emotional connection with others, typically between a child and their caregiver. This bond is crucial and forms more easily in the early years, indicating a sensitive period for emotional development. Developmental psychologists explore important questions about this process, such as: How do bonds between parents and infants develop? What impact does neglect have on these bonds? Why do children form different types of attachments?

Researchers John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth conducted studies designed to answer these questions. In the 1950s, Bowlby developed the concept of attachment theory. He defined attachment as the affectional bond that an infant forms with the parent who birthed them (Bowlby, 1969). An infant must form this bond with a primary caregiver in order to have normal social and emotional development. In addition, Bowlby proposed that this attachment bond is very powerful and continues throughout life. He used the concept of secure base to define a healthy attachment between parent and child (Bowlby, 1988). A secure base is a parental presence that gives the child a sense of safety as they explore their surroundings.

Bowlby said that two things are needed for a healthy attachment:

- The caregiver must be responsive to the child’s physical, social, and emotional needs.

- The caregiver and child must engage in mutually enjoyable interactions (Bowlby, 1969) (Figure LD.13).

While Bowlby thought attachment was an all-or-nothing process, Mary Ainsworth’s (1970) research showed otherwise. Ainsworth wanted to know if children differ in the ways they bond, and if so, why. To find the answers, she used the Strange Situation procedure to study attachment between parents and their infants (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970). In the Strange Situation, the primary caregiver and child (age 12-18 months) are placed in a room together. There are toys in the room, and the caregiver and child spend some time alone in the room. After the child has had time to explore their surroundings, a stranger enters the room. The caregiver then leaves the baby with the stranger. After a few minutes, the caregiver returns to comfort their child.

Based on how the infants/toddlers responded to the separation and reunion, Ainsworth identified three types of parent-child attachments: secure, avoidant, and ambivalent (aka. “resistant”) (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970). A fourth style, known as disorganised attachment, was later described (Main & Solomon, 1990).

Secure attachment

- Most common type of attachment.

- Toddler prefers their parent (the attachment figure) over a stranger.

- Toddler uses the attachment figure as a secure base to explore the environment.

- Toddler seeks out parent in times of stress.

- Children are distressed when caregivers leave the room in the Strange Situation experiment but happy upon their return.

- Caregivers are sensitive and responsive to their needs.

Avoidant attachment

- Child is unresponsive to the parent.

- Child does not use the parent as a secure base.

- Child does not appear to care if the parent leaves.

- Child reacts to the parent the same way they react to a stranger.

- Child is slow to show a positive reaction when the parent returns.

Ambivalent (or Resistant) attachment

- Children show clingy behaviour but may reject attachment figure’s attempts to interact.

- Children do not explore the toys in the room due to fear.

- Children become extremely disturbed and angry with the parent during separation in the Strange Situation.

- Children are difficult to comfort when the parent returns.

Disorganised attachment

- Children behave oddly or inconsistently in the Strange Situation, such as freezing, running around erratically, or trying to run away when the caregiver returns.

- Is most often seen in children who have been abused – which disrupts a child’s ability to regulate their emotions (Main & Solomon, 1990).

While Ainsworth’s research has found support in subsequent studies, it has also met criticism. Some researchers have pointed out that a child’s temperament may have a strong influence on attachment (Gervai, 2009; Harris, 2009), and others have noted that attachment varies from culture to culture, a factor not accounted for in Ainsworth’s research (Rothbaum, Weisz, Pott, Miyake, & Morelli, 2000; van Ijzendoorn & Sagi-Schwartz, 2008).

The next video explains and shows the process involved with the strange situation test, originally developed by Ainsworth.

Watch this video: The Strange Situation | Mary Ainsworth, 1969 | Developmental Psychology (4.5 minutes)

“The Strange Situation | Mary Ainsworth, 1969 | Developmental Psychology” video by Psychology Unlocked is licensed under the Standard YouTube Licence.

Just as attachment is the main psychosocial milestone of infancy, the primary psychosocial milestone of childhood is the development of a positive sense of self. How does self-awareness develop? If you place a baby in front of a mirror, they will reach out to touch their image, thinking it is another baby. However, by about 18 months a toddler will recognise that the person in the mirror is them. How do we know this? In a well-known experiment, a researcher placed a red dot of paint on children’s noses before putting them in front of a mirror (Amsterdam, 1972). Commonly known as the mirror test, this behaviour is demonstrated by humans and a few other species and is considered evidence of self-recognition (Archer, 1992).

At 18 months old they would touch their own noses during the mirror test when they saw the paint, surprised to see a spot on their faces. By 24–36 months old children can name and/or point to themselves in pictures, clearly indicating self-recognition. Children from 2–4 years old display a great increase in social behaviour once they have established a self-concept. They enjoy playing with other children, but they have difficulty sharing their possessions. Through play children practice performing gender roles (Chick, Heilman-Houser, & Hunter, 2002). By 4 years old, children can cooperate with other children, share when asked, and separate from parents with little anxiety. Children at this age also exhibit autonomy, initiate tasks, and carry out plans. =When children experience success in these areas, it contributes to a positive sense of self.

Once children reach 6 years old, they can identify themselves in terms of group memberships: “I’m a first grader!”. School-age children compare themselves to their peers and discover that they are competent in some areas and less so in others (recall Erikson’s task of industry versus inferiority). At this age, children recognise their own personality traits as well as some other traits they would like to have.

Development of a positive self-concept is important to healthy development. Children with a positive self-concept tend to be, more confident, do better in school, act more independently, and are more willing to try new activities (Maccoby, 1980; Ferrer & Fugate, 2003). Formation of a positive self-concept begins in Erikson’s toddlerhood stage, when children establish autonomy and become confident in their abilities. Development of self-concept continues in elementary school, when children compare themselves to others. When the comparison is favourable, children feel a sense of competence and are motivated to work harder and accomplish more. Self-concept is re-evaluated in Erikson’s adolescence stage, as teens form an identity. They internalise the messages they have received regarding their strengths and weaknesses, keeping some messages and rejecting others. Adolescents who have achieved identity formation are capable of contributing positively to society (Erikson, 1968).

One behavioural aspect that contributes to children’s developing sense of self-identity is play. Children spend a significant portion of their day playing; preschoolers often spend most of the day engaged in some sort of play activity. Play is an important aspect of social and cognitive development, as it makes social learning something children desire to engage in. Play also provides the space for children to begin practicing social skills, such as humour, which has been found to influence peer acceptance and perceived social competence. It has even been argued that play is an essential element in the acquisition of language and concept meaning.

Given the integral role of play in children’s lives, it becomes evident that activities such as play are not merely for entertainment but are pivotal in the development of self-concept, motivation, learning, and the establishment of secure relationships. Through play, children not only engage in essential social and cognitive development but also explore and affirm their identities, preferences, and abilities. This exploration is crucial for fostering a positive self-concept, which in turn supports confidence, independence, and a willingness to embrace new experiences. As children navigate through various stages of development, from recognising themselves in mirrors to identifying with group memberships and evaluating their competencies, play serves as a constant, enriching backdrop that enhances their understanding of themselves and their place in the world.

Parent-Child Relationship

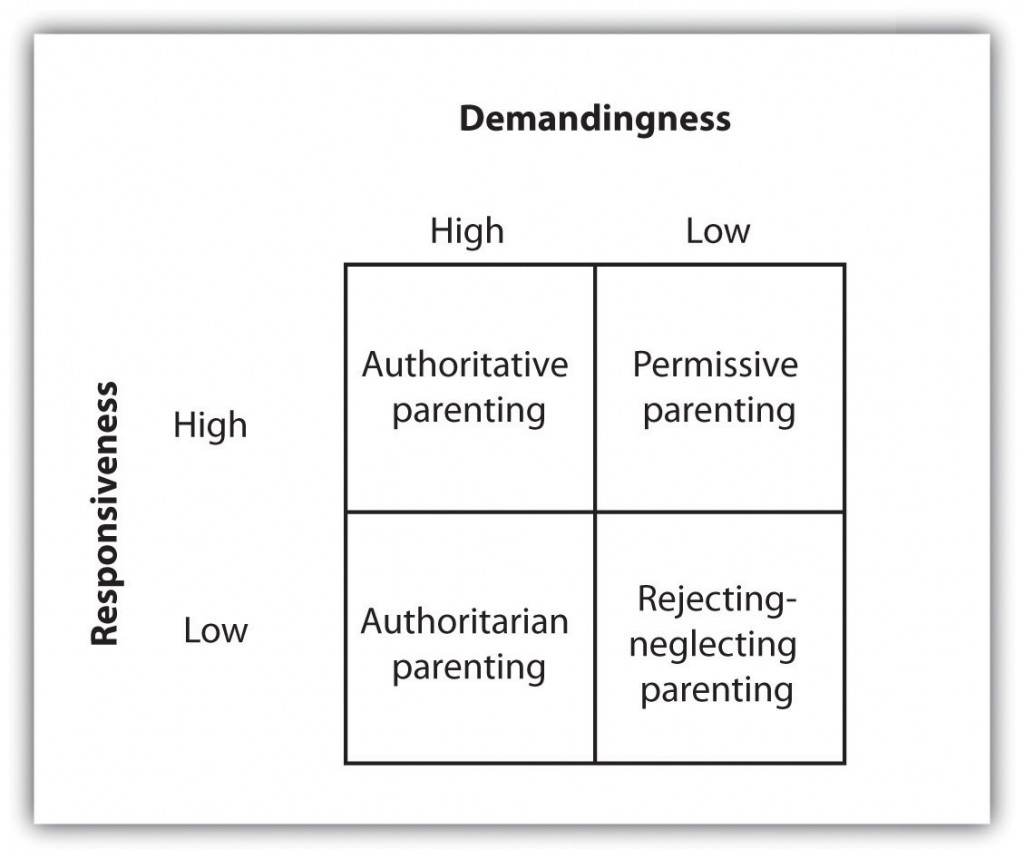

As the child grows, parents take on one of four types of parenting styles — parental behaviours that determine the nature of parent-child interactions and that guide their interaction with the child. These styles depend on whether the parent is more or less demanding and more or less responsive to the child. Authoritarian parents are demanding but not responsive. They impose rules and expect obedience, tending to give orders (“Eat your food!”) and enforcing their commands with rewards and punishment, without providing any explanation of where the rules came from except “Because I said so!” Permissive parents, on the other hand, tend to make few demands and give little punishment, but they are responsive in the sense that they generally allow their children to make their own rules. Authoritative parents are demanding (“You must be home by curfew”), but they are also responsive to the needs and opinions of the child (“Let’s discuss what an appropriate curfew might be”). They set rules and enforce them, but they also explain and discuss the reasons behind the rules. Finally, rejecting-neglecting parents are undemanding and unresponsive overall.

Parenting styles can be divided into four types, based on the combination of demandingness and responsiveness. The authoritative style, characterized by both responsiveness and also demandingness, is the most effective.

Many studies of children and their parents, using different methods, measures, and samples, have reached the same conclusion — namely, that authoritative parenting, in comparison to the other three styles, is associated with a wide range of psychological and social advantages for children. Parents who use the authoritative style, with its combination of demands on the children as well as responsiveness to the children’s needs, have kids who show better psychological adjustment, school performance, and psychosocial maturity compared with the kids of parents who use the other styles (Baumrind, 1996; Grolnick & Ryan, 1989).

Adolescence

Brain Development

The adolescent brain also remains under development. Up until puberty, brain cells continue to bloom in the frontal region. Adolescents engage in increased risk-taking behaviours and emotional outbursts, possibly because the frontal lobes of their brains are still developing (Figure LD.14). Recall that this area is responsible for judgment, impulse control, and planning, and it is still maturing into early adulthood (Casey, Tottenham, Liston, & Durston, 2005).

Watch this video: Tricky Topics: Myelination of the Prefrontal Cortex (4 minutes)

“Tricky Topics: Myelination of the Prefrontal Cortex” video by FirstYearPsych Dalhousie is licensed under the Standard YouTube Licence.

Cognitive Development

More complex thinking abilities emerge during adolescence. Some researchers suggest that this is due to increases in processing speed and efficiency rather than as the result of an increase in mental capacity; in other words, due to improvements in existing skills rather than development of new ones (Bjorkland, 1987; Case, 1985). During adolescence, teenagers move beyond concrete thinking and become capable of abstract thought. Recall that Piaget refers to this stage as formal operational thought. Teen thinking is also characterised by the ability to consider multiple points of view, imagine hypothetical situations, debate ideas and opinions (e.g., politics, religion, and justice), and form new ideas (Figure LD.16). In addition, it’s not uncommon for adolescents to question authority or challenge established societal norms.

Cognitive empathy, also known as theory-of-mind (which we discussed earlier with regard to egocentrism), relates to the ability to take the perspective of others and feel concern for others (Shamay-Tsoory, Tomer, & Aharon-Peretz, 2005). Cognitive empathy begins to increase in adolescence and is an important component of social problem-solving and conflict avoidance.

Psychosocial Development

Adolescents continue to refine their sense of self as they relate to others. Erikson referred to the task of the adolescent as one of identity versus role confusion. Thus, in Erikson’s view, an adolescent’s main questions are “Who am I?” and “Who do I want to be?” Some adolescents adopt the values and roles that their parents expect of them. Other teens develop identities that are in opposition to their parents but align with a peer group. This is common as peer relationships become a central focus in adolescents’ lives.

As adolescents work to form their identities, they pull away from their parents, and the peer group becomes very important (Shanahan, McHale, Osgood, & Crouter, 2007). Despite spending less time with their parents, most teens report positive feelings toward them (Moore, Guzman, Hair, Lippman, & Garrett, 2004). Warm and healthy parent-child relationships have been associated with positive child outcomes, such as better grades and fewer school behaviour problems, in the United States as well as in other countries (Hair et al., 2005). It appears that most teens don’t experience adolescent storm and stress to the degree once famously suggested by G. Stanley Hall, a pioneer in the study of adolescent development. Only small numbers of teens have major conflicts with their parents (Steinberg & Morris, 2001), and most disagreements are minor. For example, in a study of over 1,800 parents of adolescents from various cultural and ethnic groups, Barber (1994) found that conflicts occurred over day-to-day issues such as homework, money, curfews, clothing, chores, and friends. These types of arguments tend to decrease as teens develop (Galambos & Almeida, 1992).

There is emerging research on the adolescent brain. Galvan, Hare, Voss, Glover, and Casey (2007) examined its role in risk-taking behaviour. They used fMRI to assess the readings’ relationship to risk-taking, risk perception, and impulsivity. The researchers found that there was no correlation between brain activity in the neural reward centre and impulsivity or risk perception. However, activity in that part of the brain was correlated with taking risks. In other words, risk-taking adolescents experienced brain activity in the reward centre. The idea, however, that adolescents are more impulsive than other demographics was challenged in their research, which included children and adults.

Emerging Adult (Ages 18 to 29)

Let’s now consider the relatively new-to-psychology concept of “emerging adulthood”. This developmental stage covers psychological, social, and spiritual development between ages 18 and 29. Jeffrey Arnett, a psychology researcher, proposed this distinct phase in human development (Arnett, 2000). The emergence of this developmental stage can be attributed to various societal shifts, such as later ages of marriage and parenthood and extended periods spent in higher education (Arnett, 2000). Our understanding of emerging adulthood and its impact on later life stages is still developing.

This Emerging Adult stage acts as a developmental crucible where patterns are formed that can shape a person’s entire life path. It acts as a developmental crucible where patterns are formed that can shape a person’s entire life trajectory (Arnett, 2000). Behaviours, values, relationships, and more are moulded during this time.

There are five primary characteristics that define this developmental stage: identity exploration, instability, self-focus, feeling ‘in-between’, and possibilities. Identity exploration stands at the centre, with the other four elements extending from it. This exploration stage involves emerging adults navigating new identities around love, work, and worldview, influencing their long-term life directions and commitments (Arnett, 2000).

- Identity Exploration: This is when young adults explore different aspects of who they are, trying out various roles, beliefs, and career paths to find what fits them best. It’s a time of questioning and discovering oneself in areas like love, work, and personal beliefs.

- Instability: This refers to the changes and uncertainties in life during emerging adulthood, such as moving frequently, changing jobs, or experiencing shifts in relationships. It’s a period marked by transitions and a lack of permanence in various aspects of life.

- Self-focus: During this stage, individuals focus more on themselves as they make decisions that will shape their future. It’s a time of independence, where there’s less concern about others’ expectations and more emphasis on personal growth and self-discovery.

- Feeling ‘In-Between’: This is the sensation of being caught between adolescence and full-fledged adulthood. Emerging adults often feel they are no longer teenagers but not yet fully adults, navigating a middle ground as they work towards adult responsibilities and independence.

- Possibilities: This characteristic highlights the optimism and sense of opportunity prevalent in emerging adulthood. It’s a time when individuals feel that many paths are open to them, and they can envision numerous potential futures, filled with hope for achieving their dreams.

In conclusion, emerging adulthood is a relatively modern societal phenomenon in response to delaying parenthood and extended years in higher education. Arnett argues that emerging adulthood is an integral and unique phase in human development. It is a period where lifelong patterns are set, identities are explored, and significant transitions are made, ultimately shaping an individual’s future life trajectory (Arnett, 2000). While the emerging adult stage is useful, it is problematic that it is built upon young adults living in the gap before having a family (individualistic and exclusionary of people who raise children in their early 20s) and the requirement of staying in higher education (elitist and expensive) for a longer period.

Technology’s Impact on the Development of Children and Youth

The impact of technology on the development of children and youth is significant, touching on various aspects of their lives. This summary provides a general overview of how television, cell phones, social media, and video games affect young people.

Television

Television has both positive and negative effects on children. Educational programs, like “Sesame Street”, can promote learning and improve academic skills (Linebarger & Walker, 2005). However, watching too much TV can cut into reading time, which leads to lower reading scores and attention problems in children (Williams, 1986). This means that when children spend a lot of time watching TV, they might not do as well in school or might have trouble focusing. Also, watching violent TV shows is linked to an increase in aggressive behaviours under some circumstances (Anderson et al., 2001).

Cell Phones

Cell Phones are everywhere and are used by children and teenagers for talking, texting, and going online. They can be useful for staying in touch with friends and family and for learning. But, using cell phones too much can distract users from homework and lead to stress (Lepp et al., 2015). For young people who feel left out or different, cell phones can offer support through social networks. However, since cell phones are a major way that children and youth access social media, these devices can also be a way for people who bully to target young phone users (Hinduja & Patchin, 2010).

Social Media

Social Media platforms like Instagram and Snapchat allow children and teenagers to express themselves, share photos, and connect with friends. These platforms can be especially important for young people who feel marginalised, giving them a space to find others with similar experiences (Craig & McInroy, 2014). But, spending a lot of time on social media is linked to feeling anxious, depressed, and lonely (Twenge et al., 2018). This is because constant comparison with others online can make young people feel bad about themselves.

Video Games

Video Games can be fun and can also teach problem-solving skills. However, games with violent content might make children more likely to act aggressively (Anderson et al., 2010). The world of video games often lacks diversity, which means that not all children see themselves represented in the games they play. This can make some feel left out or stereotyped (Williams et al., 2009). Games that include different kinds of characters and stories can help make gaming a more positive experience for everyone.

In summary, technology can help children learn and stay connected, but it also has downsides like distraction, stress, and exposure to harmful content. It’s important for children to have a balanced approach to using technology. This means enjoying the benefits of technology while also being aware of the risks and knowing how to manage them. Parents, teachers, and caregivers can help by setting limits on screen time, talking about what children are watching or playing, and encouraging them to spend time offline too.

When Harm Impacts Healthy Development: The Impact of the Indian Residential School System

Content Disclosure: This section contains discussions on the psychological and physiological impacts of stress, with a focus on the historical trauma experienced by Indigenous communities, particularly related to Indian Residential Schools. It includes descriptions of trauma, cultural genocide, and abuse, which may be distressing or triggering for some readers. The content is presented with a trauma-informed approach and includes both scientific terminology and plain language explanations. Please consider your comfort level with these topics before reading.

Childhood and adolescence are life stages pivotal to a person’s developmental maturation (Cabral & Patel, 2020; Cassidy & Shaver, 2018; White et al., 2017). Experiences such as adversity, loss, trauma, and/or maltreatment have been linked to feelings of anxiety and depression (Hovens et al., 2015; Jurena et al., 2020) as well as issues with attachment in older adult relationships (Cohen et al., 2012; Lo et al., 2017), issues in development (Sege et al., 2017), and other health problems (Asselmann et al., 2018; Nelson et al., 2020; Rojo-Wissar et al., 2021).

Since confederation (1867), the Canadian federal government has continued to forcefully attempt total assimilation of Indigenous Peoples into “Euro-Canadian culture and society” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission [TRC], 2015). One of the ways in which the government attempted to do this was through the Indian Residential School (IRS) system (TRC, 2015). The IRS system in Canada has often been referred to as a series of concentration camps (TRC, 2015) or “boarding schools”used to house Indigenous children. Unlawful and immoral acts perpetuated in the IRSs have been termed “cultural genocide” at the international level (TRC, 2015; United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [UNDRIP], 2007).

Impact on Attachment

From 1876 to 1996, the Canadian government took hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children, some as young as 4, from their families and placed them in residential schools (IRSs) (TRC, 2015). If Indigenous parents or family members tried to stop the police from taking their children, they could be jailed or even killed (Bombay et al., 2014ab; Facing History and Ourselves, 2021; TRC, 2015). At these schools, children were often forced to change their appearance drastically and were not allowed to use their names or speak their native languages. Instead, they were given numbers and punished if they spoke their own language, which for many was the only language they knew (TRC, 2015). Being separated from family under such stressful conditions can cause long-term health issues. Research shows that short-term separations can harm health later in life (Räikkönen et al., 2011), and longer separations increase the risk of depression (Bohman et al., 2017; Coffino, 2009) and anxiety (Bryant et al., 2017; Lähdepuro et al., 2019).

Intergenerational Impacts

Federal, institutional and academic inquiries into the IRS system continue to highlight various atrocities that many IRS Survivors experienced, such as spiritual, verbal, emotional, physical and sexual assault, abuse and violence (TRC, 2015). Trauma of this magnitude continues to impact not only the Survivors, but their children, grandchildren, and other relatives (Bombay et al., 2014ab; Bombay et al., 2014ab; Lehrner & Yehuda, 2018). For example, Indigenous children of IRS Survivors are more likely to have poor psychological health because of the IRS impacts on their parents’ psychosocial functioning and health (Bombay et al., 2011; 2014ab; 2018; Elias et al., 2012).

Biopsychosocial Framework

The Biopsychosocial Framework shows how our health is influenced by a mix of biological, psychological, and social factors. It’s a tool that helps health professionals understand why certain physical or mental health problems happen (Karunamuni et al., 2020). This approach reveals that the education provided by many residential schools was substandard, with poor teaching, inadequate resources, and a high level of racism (Barnes & Josefowitz, 2019; TRC, 2015). As a result, many survivors left school without the necessary academic skills, such as language proficiency, and were often unprepared for work as adults (Miller, 1996; TRC, 2015; Barnes et al., 2006). The deep trauma from their experiences at these schools has led many survivors to face challenges with their mental and physical health, their ability to connect with Indigenous cultural practices and communities, and their overall well-being (Barnes & Josefowitz, 2019; Ogle et al., 2013; Miller, 1996; TRC, 2015; Vachon et al., 2015).

You can read more about the effects of trauma and stress in the chapter on Well-being.

Cultural Resilience

While Indigenous Peoples in Canada continue to face premeditated colonial assimilation tactics, such as the child welfare crisis or “modern day IRS system” (Ma et al., 2019; McMillan, 2021; Mitchell, 2019), resilience among Indigenous populations in Canada continues to be researched (Bombay et al., 2010; 2011; Paul et al., 2022). To date, various facets of cultural identity among Indigenous populations in Canada, such as the sense of belonging to a cultural community, provide protection against the negative effects of colonization (Bombay et al., 2014ab; First Nations Health Authority, 2019; Paul et al., 2022). While it has been suggested that Indigenous culture helps to improve and maintain good health and happiness for Indigenous individuals, continued research is needed to better understand precisely how these cultural wisdoms and practices can be used in care models that are most suitable for and respectful of Indigenous People.

Summary

In our exploration of “Ages, Stages, and Milestones of Development”, we have studied human growth from the earliest moments of conception to the phase of emerging adulthood. This section has highlighted the biological, cognitive, and psychosocial transformations that occur, each stage building upon the last to shape the complex individuals we become. By examining attachment, self-concept, and the unique challenges of adolescence, we’ve gained a holistic understanding of the developmental process. It is also important to be mindful of how technologies such as TV, cell phones, social media, and video games can benefit and interfere with healthy development.

The profound impact of the Indian Residential School system on Indigenous communities underscores the importance of understanding how adverse experiences shape developmental pathways. Childhood and adolescence are critical stages for building healthy attachments and self-concepts, but trauma and loss can significantly hinder this process.

Our lifespan involves many developmental pathways, from prenatal factors to societal impacts, that contribute to our physical, emotional, mental, social, and spiritual growth. Rather than being solely negative influences in our lives, developmental challenges and setbacks can inspire us to look for solutions, build resilience, and open us up to new learning experiences, enriching our journey through life’s varied stages and seasons.