An Introduction to Biological Anthropology

Katie Nelson, Ph.D., Inver Hills Community College

Lara Braff, Ph.D., Grossmont College

Beth Shook, Ph.D., California State University, Chico

Kelsie Aguilera, M.A., University of Hawai‘i: Leeward Community College

This introduction is a section of a revision from “Chapter 1: Introduction to Biological Anthropology” by Katie Nelson, Lara Braff, Beth Shook, and Kelsie Aguilera. In Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology, first edition, edited by Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera, and Lara Braff, which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Introductory Statement

This preliminary section offers an overview of the discipline of Anthropology. Students who have previously completed an introductory course (such as ANTH 202 or its equivalent) will likely find the material familiar. Although reviewing this section is recommended, those confident in their understanding of Anthropology and its four subdisciplines may choose to proceed directly to Chapter 1. It is important to note that this textbook reflects an American approach to organizing the discipline; in other academic traditions, anthropological knowledge may be divided into different disciplinary frameworks.

Learning Objectives

- Describe anthropology and the four subdisciplines.

- Explain the main anthropological approaches.

- Define biological anthropology, describe its key questions, and identify major subfields

Diving in caves along the Caribbean coast of Mexico, archaeologist Octavio del Rio and his team spotted something unusual in the sand 26 feet below the ocean surface. As they swam closer, they suspected it could be a bone—and likely a very ancient one, as this cave system is inaccessible today without modern diving equipment. However, in the distant past, these caves were dry land formations high above the ocean. The divers ended up recovering not just one but many bones from the site. Eventually they were able to reconstruct an 80% complete human skeleton that they named “Eve of Naharon.” Dated to 13,600 years ago, she is (as of today) the oldest known North American skeleton (TANN 2018).

Who was Eve? What was her life like? How did she end up in the cave? What can we learn about her from the bones she left behind? Anthropologists have determined that Eve was 4.6 feet tall, had a broken back, and died in her early 20s. Although it is rare to find an ancient, nearly complete skeleton in the ocean depths, Eve is not the only such find. In underwater caves along Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, archaeologists have found eight well-preserved skeletons dated between 9,000 to 13,000 years old. With each new discovery—whether it is a skeleton in North America, fossil footprints in Tanzania, or a mandible with teeth in China—we come another step closer to understanding the evolution of our species.

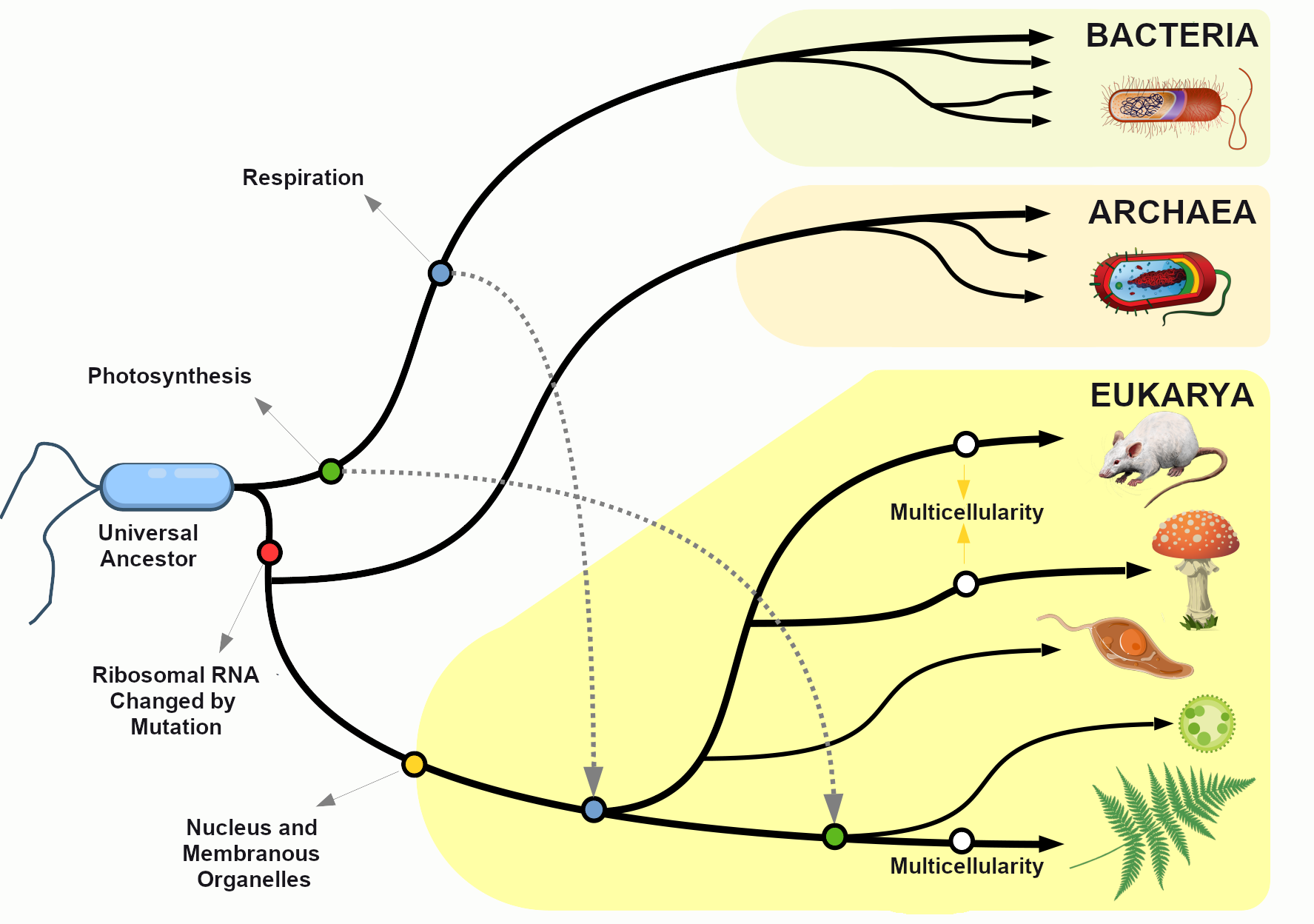

Biological anthropologists study when and how human beings evolved; their intriguing findings are the focus of this book. Biological anthropology is one of four subdisciplines within anthropology; the others are cultural anthropology, archaeology, and linguistic anthropology. All anthropological subdisciplines seek to better understand what it means to be human.

What is Anthropology?

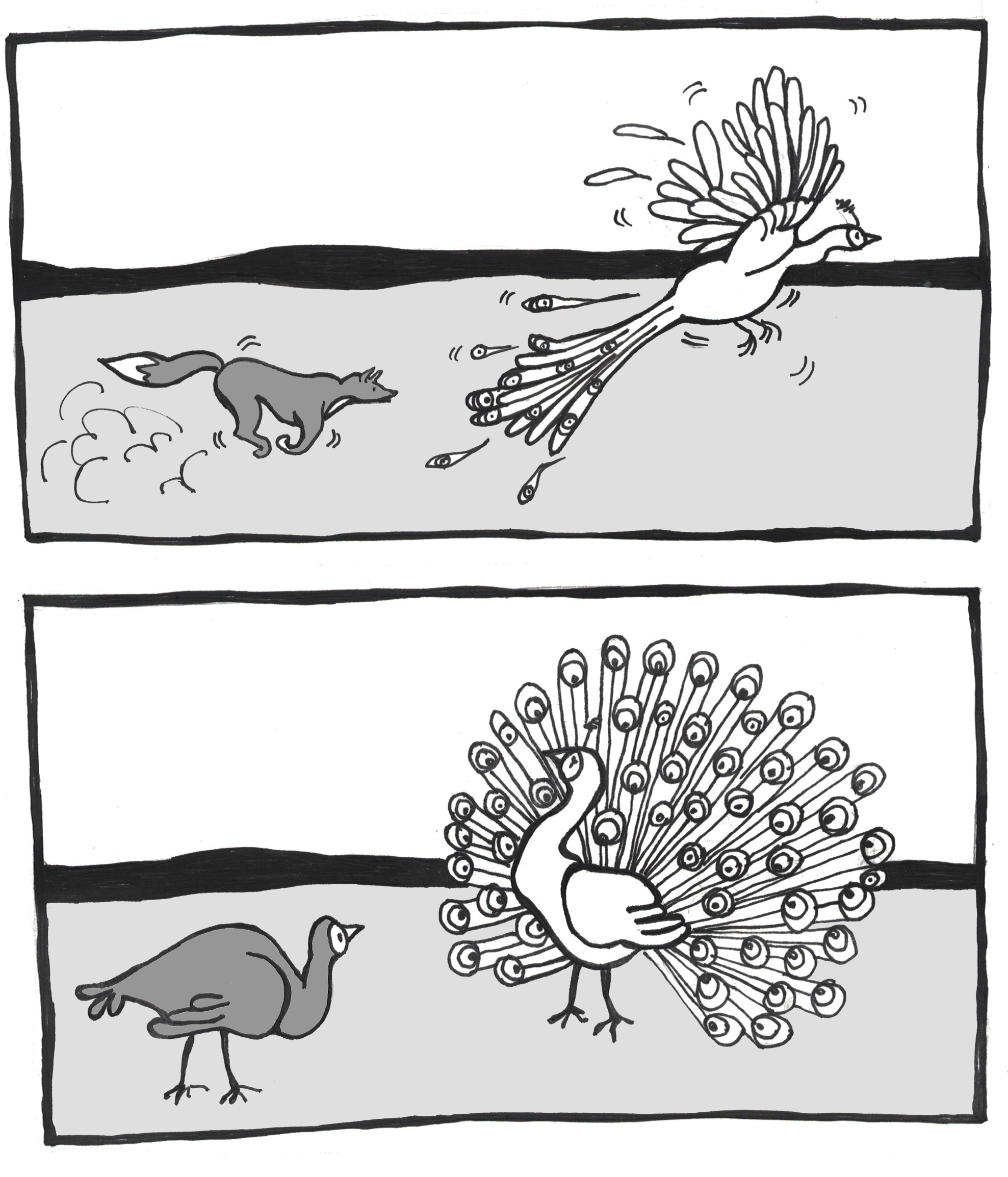

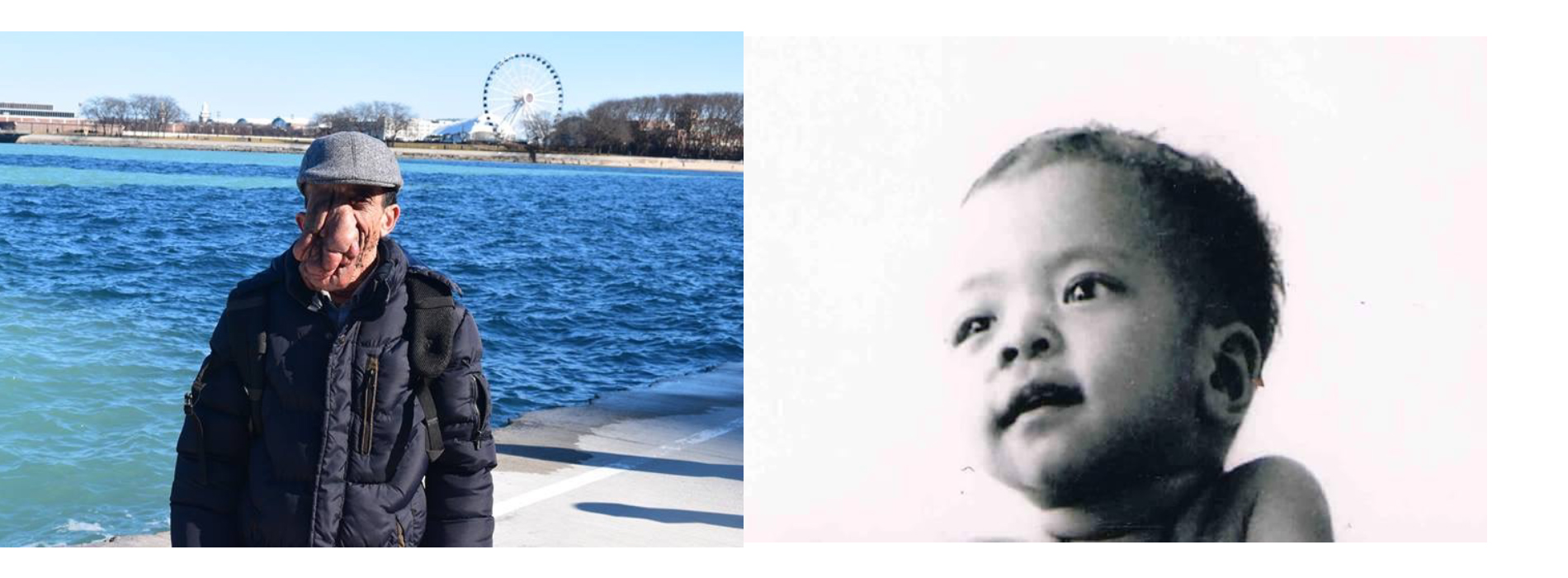

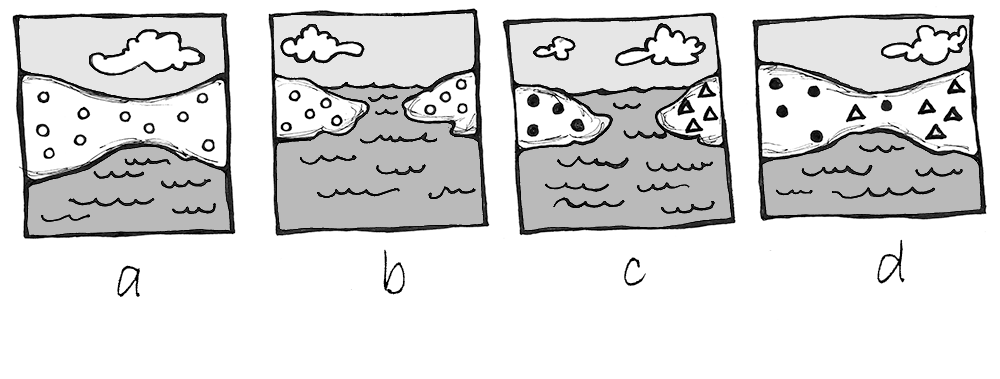

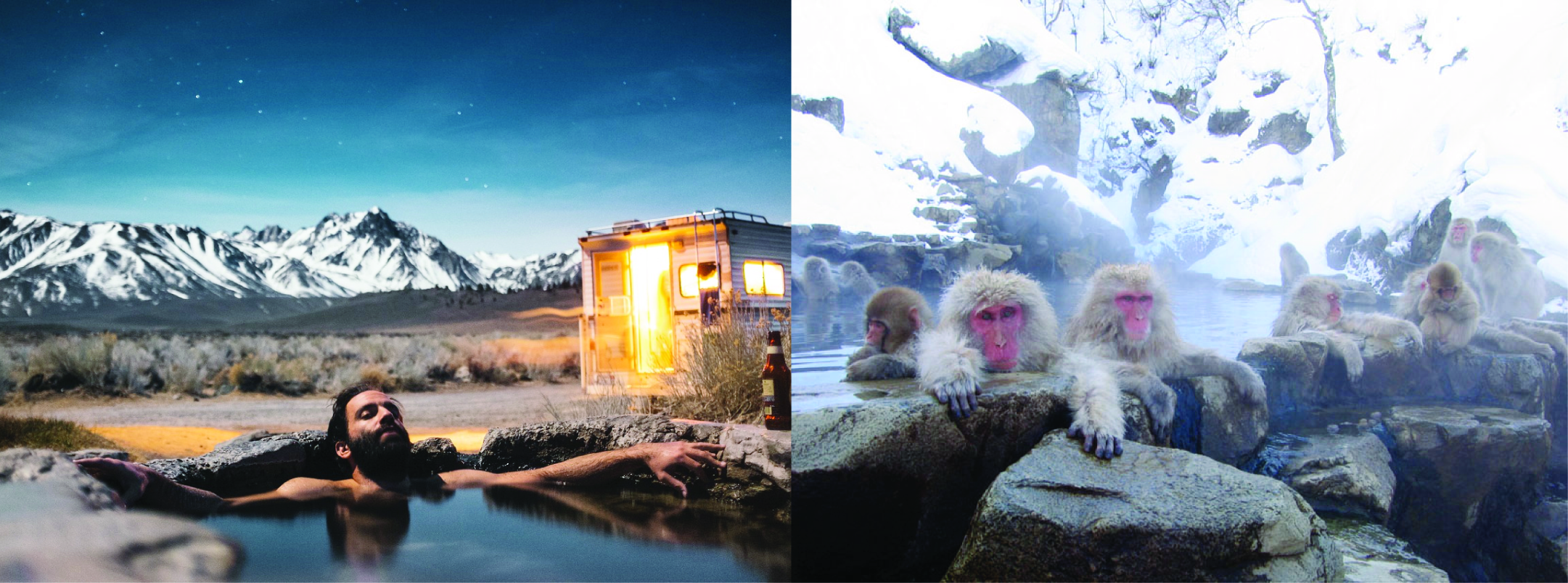

Why are people so diverse (Figure 1.1)? Some people live in the frigid Arctic tundra, others in the arid deserts of sub-Saharan Africa, and still others in the dense forests of Papua New Guinea. Human beings speak more than 6,000 distinct languages. Some people are barely five feet tall while others stoop to fit through a standard door frame. What makes people, around the world, look, speak, and behave differently from one another? And what do all humans share in common?

Anthropology is a discipline that explores human differences and similarities by investigating our biological and cultural complexity, past and present. Derived from Greek, the word –anthropos means “human” and –logy refers to the “study of.” Therefore, anthropology is, by definition, the study of humans. Anthropologists are not the only scholars to focus on the human condition; biologists, sociologists, psychologists, and others also examine human nature and societies. However, anthropology is a uniquely dynamic, multifaceted discipline that emerged from a deep-seated curiosity about who we are as a species.

The Subdisciplines

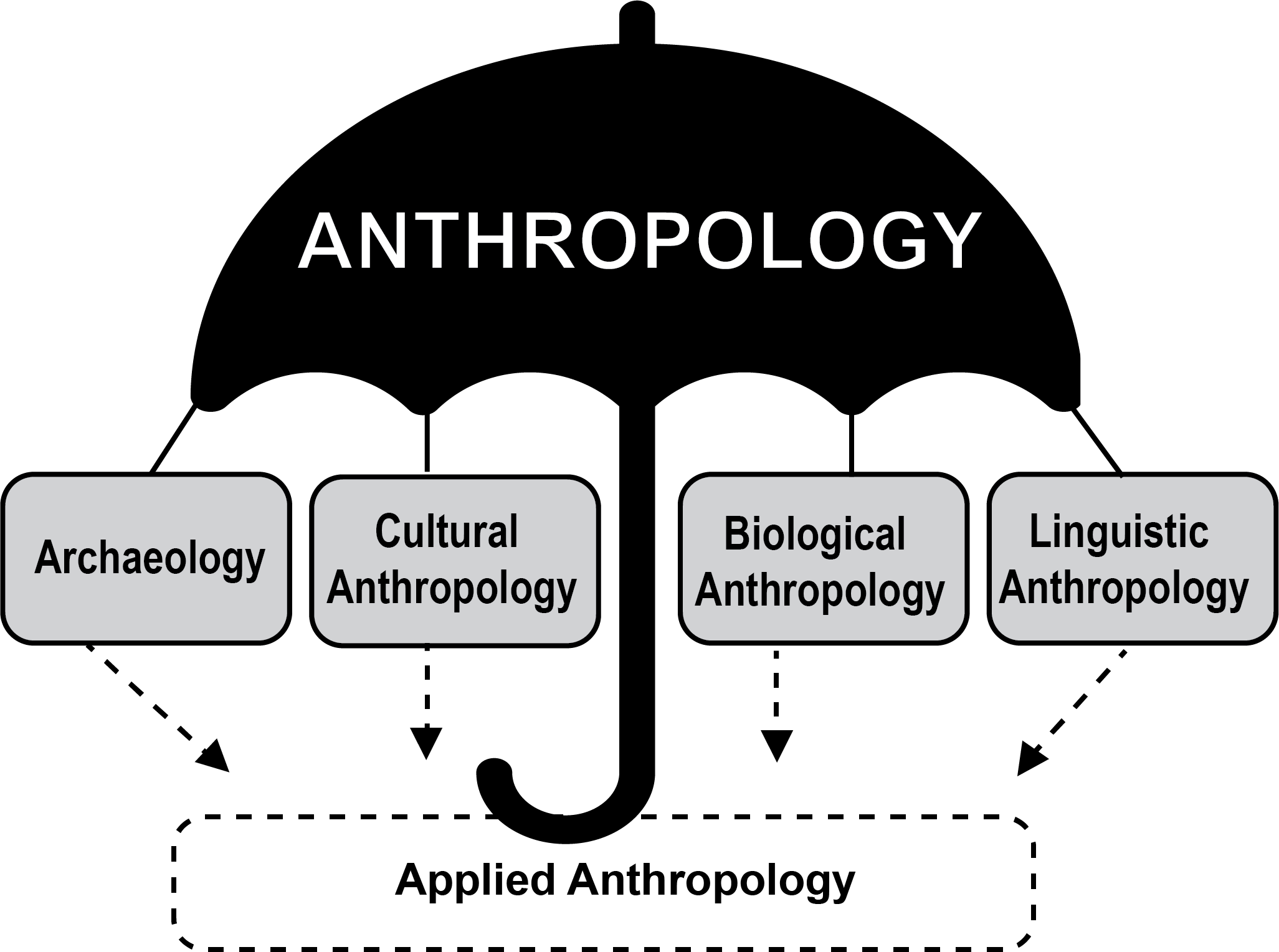

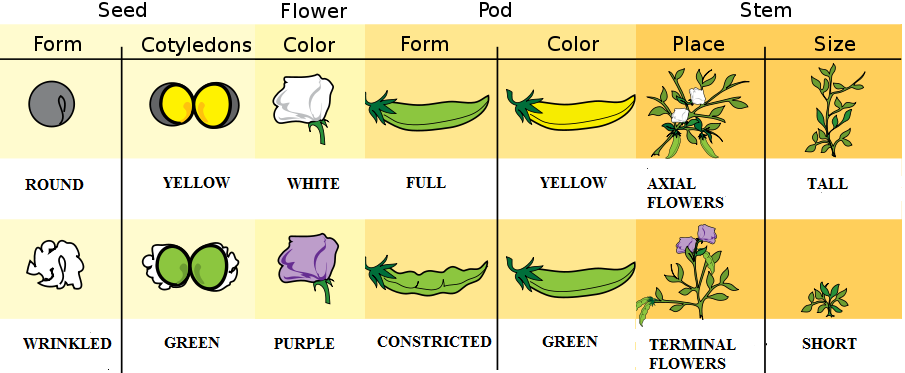

In the United States, the discipline of anthropology includes four subdisciplines: cultural anthropology, biological anthropology, archaeology, and linguistic anthropology. In addition, applied anthropology is sometimes called the fifth subdiscipline (Figure 1.2). Each of the subdisciplines provides a distinct perspective on the human experience. Some (like biological anthropology) use the scientific method to develop theories about human origins, evolution, material remains, or behaviors. Others (like cultural anthropology) use humanistic and interpretive approaches to understand human beliefs, languages, behaviors, cultures, and societies. Findings from all subdisciplines, together, contribute to a multifaceted appreciation of human biocultural experiences, past and present.

Cultural Anthropology

Cultural anthropologists focus on similarities and differences among living persons and societies. They suspend their sense of what is expected in their own culture in order to understand other perspectives without judging them (cultural relativism). They learn these perspectives through participant-observation fieldwork. Beyond describing another way of life, cultural anthropologists ask broader questions about humankind: Are human emotions universal or culturally distinct? Is maternal behavior learned or innate? How and why do groups migrate to new places? For cultural anthropologists, no aspect of human life is outside their purview: They study art, religion, medicine, migration, natural disasters, even video gaming. While many cultural anthropologists are intrigued by human diversity, they recognize that people around the world share much in common.

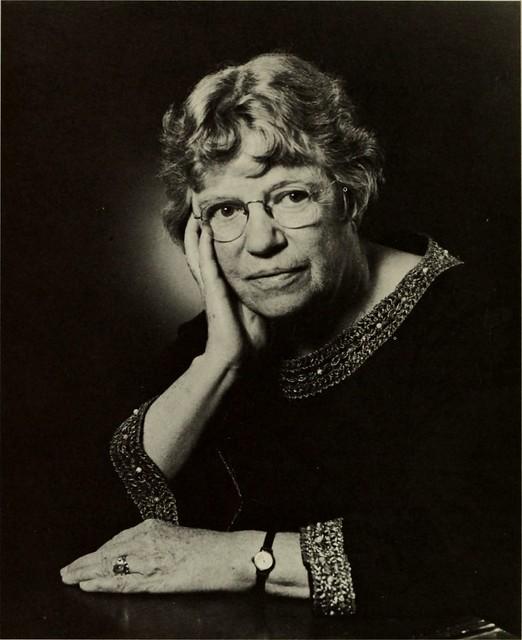

One famous U.S. cultural anthropologist, Margaret Mead (1901–1978, Figure 1.3), conducted cross-cultural studies of gender and socialization. In the early twentieth century, people in the U.S. wondered if the emotional turbulence exhibited by American adolescents was caused by the biology of puberty, and thus natural and universal. To find out, Mead went to the Samoan Islands, where she lived for several months getting to know Samoan teenagers. She learned that Samoan adolescence was relatively tranquil and happy. Based on her fieldwork, Mead wrote Coming of Age in Samoa, a best-selling book that was both sensational and scandalous (Mead 1928). In it, she critiqued U.S. parenting as restrictive in contrast to Samoan parenting, which allowed teenagers to freely explore their community and even their sexuality. Ultimately, she argued that nurture (i.e., socialization) more than nature (i.e., biology) shaped adolescent development. Despite her expressed relativism, she has been critiqued recently for exploiting the people she studied.

Cultural anthropologists do not always travel far to learn about human experiences. In the 1980s, American anthropologist Philippe Bourgois (1956–) asked how pockets of extreme poverty persist in the United States, a country widely perceived as wealthy with an overall high quality of life compared to other countries. To answer this question, he lived with Puerto Rican drug dealers in East Harlem, contextualizing their experiences both historically and presently, in terms of ongoing social marginalization and institutional racism. Rather than blame drug dealers for their choices, Bourgois argued that both individual choices and social inequality can trap people in the overlapping worlds of drugs and poverty (Bourgois 2003).

Linguistic Anthropology

The study of people is incomplete without attending to language, a defining trait of human beings. While other animals have communication systems, only humans have complex symbolic languages—and more than 6,000 of them! Human language makes it possible to teach and learn, plan and think abstractly, coordinate our efforts, and contemplate our own demise. Linguistic anthropologists ask questions like: How did language first emerge? How has it evolved and diversified over time? How has language helped our species? How can linguistic style convey social identity? How does language influence our worldview? Some linguistic anthropologists track the emergence and diversification of languages, while others focus on language use in social context. Still others explore how language is crucial to socialization: children learn their culture and identities through language and nonverbal forms of communication (Ochs and Schieffelin 2017; Figure 1.4).

One line of linguistic anthropological research focuses on the relationships among language, thought, and culture. For example, Benjamin Whorf (1897–1941) observed that whereas the English language has grammatical tenses to indicate past, present, and future, the Hopi language does not; instead, it indicates whether or not something has “manifested.” Whorf argued that this grammatical difference causes English and Hopi speakers to think about time in distinct ways: English speakers think about time in a linear way, while Hopi think about time in terms of a cycle of things or events that have manifested or are manifesting (Whorf 1956). Based on his research, Whorf developed a strong version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (also known as linguistic relativity), which states that language shapes thought. Some critics, like German American linguist Ekkehart Malotki (1938–), recognized that English and Hopi tenses differ but argued against Whorf by claiming that the Hopi language does, in fact, have linguistic terms for time and that a linear sense of time may be universal (Malotki 1983). Nevertheless, anthropological linguists tend to see human languages as a unique form of communication, linked to our ability to think and process our world.

Archaeology

Archaeologists focus on material remains—tools, pottery, rock art, shelters, seeds, bones, and other objects—to better understand people and societies. Archaeologists ask specific questions like: How did people in a particular area live? How did they utilize their environment? What happened to their society? They also ask general questions about humankind: When did our ancestors begin to walk on two legs? How and why did they leave Africa? Why did humans first develop agriculture? How did the first cities develop?

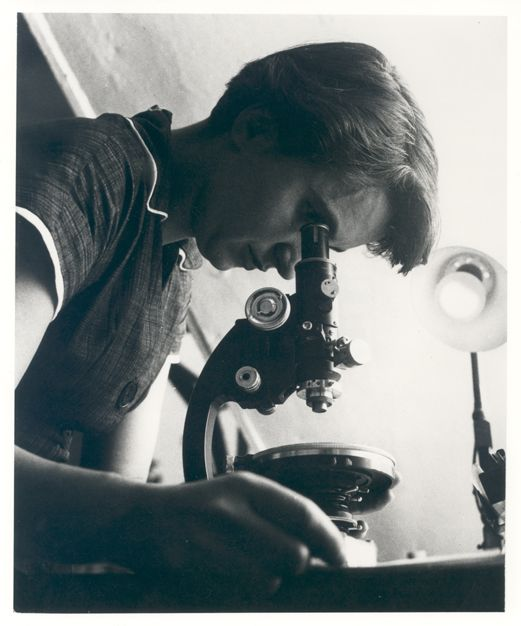

One critical method that archaeologists use to answer these questions is excavation, which involves carefully digging and removing sediment to uncover material remains while recording their context. Take the example of Kathleen Kenyon (1906–1978), a British archaeologist and one of few female archaeologists in the 1940s. While excavating at Jericho, which dates back to 10,000 BCE (Figure 1.5), she discovered city structures and cemeteries built during the Early Bronze Age (3,200 YBP in Europe). Based on her findings, she argued that Jericho is the oldest city continuously occupied by different groups of people for thousands of years (Kenyon 1979).

While most archaeologists study the past, some excavate at contemporary sites to gain new perspectives on present-day societies. For example, participants in the Garbage Project, which began in the 1970s in Tucson, Arizona, excavate modern landfills as if they were a conventional dig site. They have found that what people say they throw out differs from what is actually in the trash. The landfill holds large amounts of paper products (that people claim to recycle) as well as construction debris (Rathje and Murphy 1992). This finding indicates the need to create more environmentally conscious waste-disposal practices.

Biological Anthropology

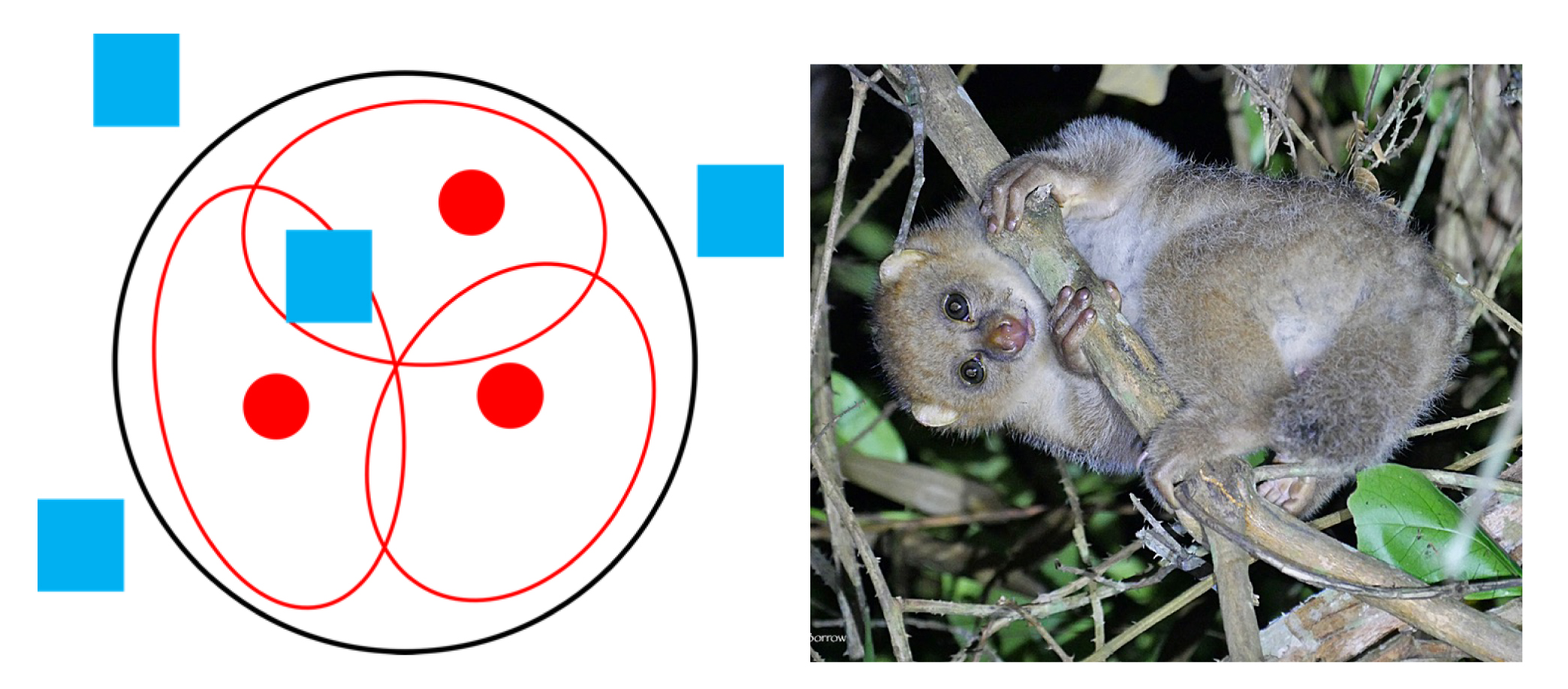

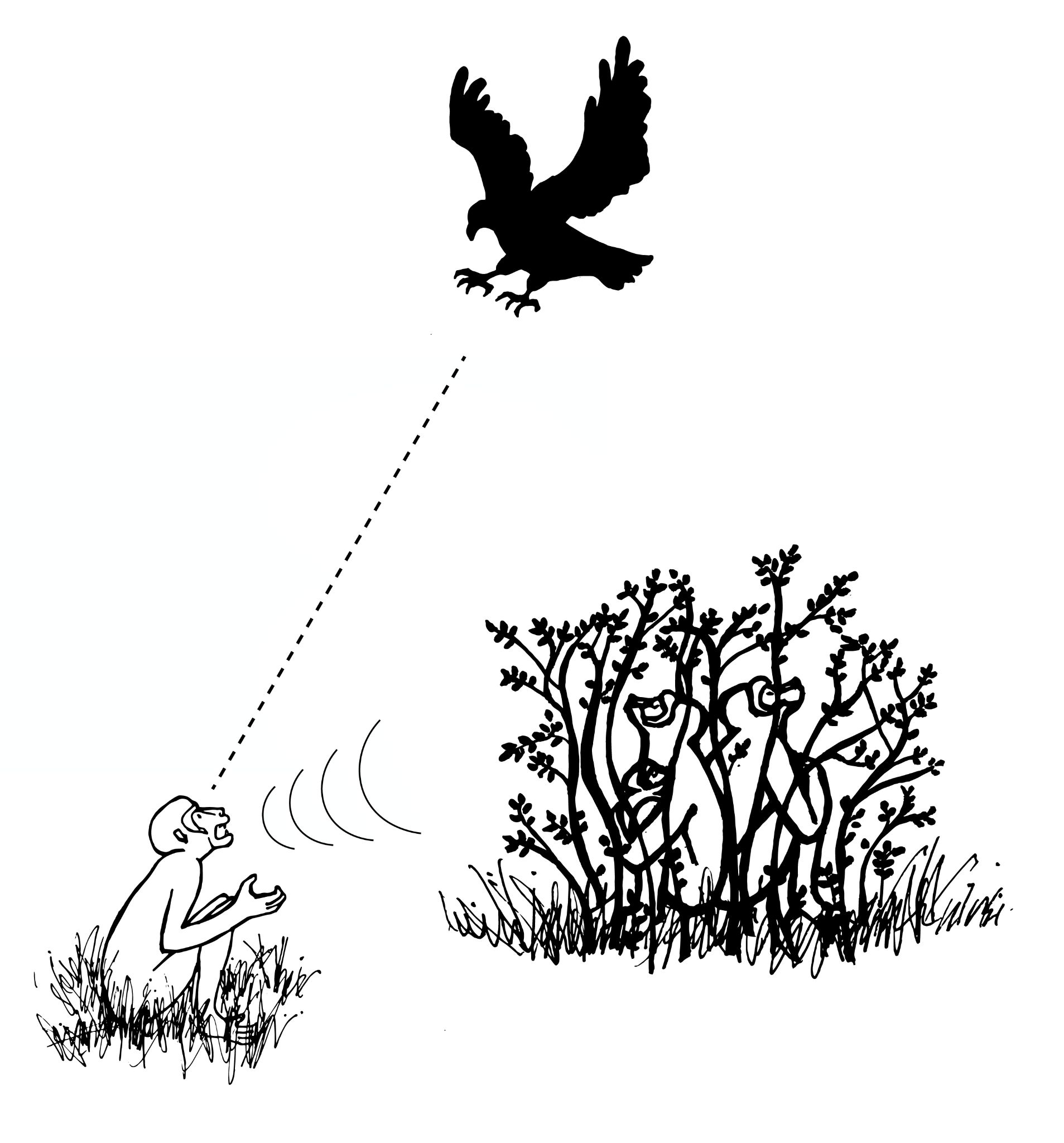

Biological anthropology—the focus of this book—is the study of human evolution and biological variation. Some biological anthropologists study our closest living relatives—monkeys and apes—to learn how nonhuman and human primates are alike and how they differ both biologically and behaviorally (Figure 1.6). Other biological anthropologists focus on extinct human species and subspecies, asking questions like: What did they look like? What did they eat? When did they start to speak? How did they adapt to new environments? Still other biological anthropologists focus on modern human diversity, asking questions about the evolution of traits, like lactose tolerance or skin color, that differ between populations. Throughout this book, we will learn about biological anthropological research that explores our nonhuman primate cousins, the origins of hominins (i.e. humans and fossil human relatives), how they adapted over time, and how we – modern humans – continue to change.

Applied Anthropology

Sometimes considered the fifth subdiscipline, applied anthropology involves the practical application of anthropological theories, methods, and findings to solve real-world problems. Applied anthropologists span the subdisciplines. An applied archaeologist might work in cultural resource management to assess a potentially significant archaeological site unearthed during a construction project. An applied cultural anthropologist could work for a technology company that seeks to understand how people interact with their products in order to design them better. Applied anthropologists are employed outside of academic settings, in public and private sectors, including business firms, advertising companies, city government, law enforcement, hospitals, nongovernmental organizations, and even the military.

Trained as both a physician and anthropologist, Paul Farmer (1959–2022, Figure 1.7) demonstrated the potential of applied anthropology to improve lives. As a college student in North Carolina, Farmer became interested in the Haitian migrants working on nearby farms. This led him to visit Haiti, the most resource-poor country in the Western Hemisphere, where he was struck by the deprived state of its health care facilities. Years later, he would return to Haiti, as a physician, to treat diseases that had been largely eradicated in the United States, such as tuberculosis and cholera. Drawing on his anthropological training, he also did fieldwork and wrote books that contextualize the suffering of Haitians in relation to historical, social, and political conditions (Farmer 2006). Finally, as an applied anthropologist, he took action by co-founding Partners in Health, a nonprofit organization that establishes health clinics in resource-poor countries and trains local staff to administer care.

Anthropological Approaches

Each of the four main anthropological subdisciplines contributes to our understanding of humankind by exploring cultures, languages, material remains, and biological adaptations. To study these phenomena, anthropologists draw upon distinct research approaches, including holism, comparison, dynamism, and fieldwork.

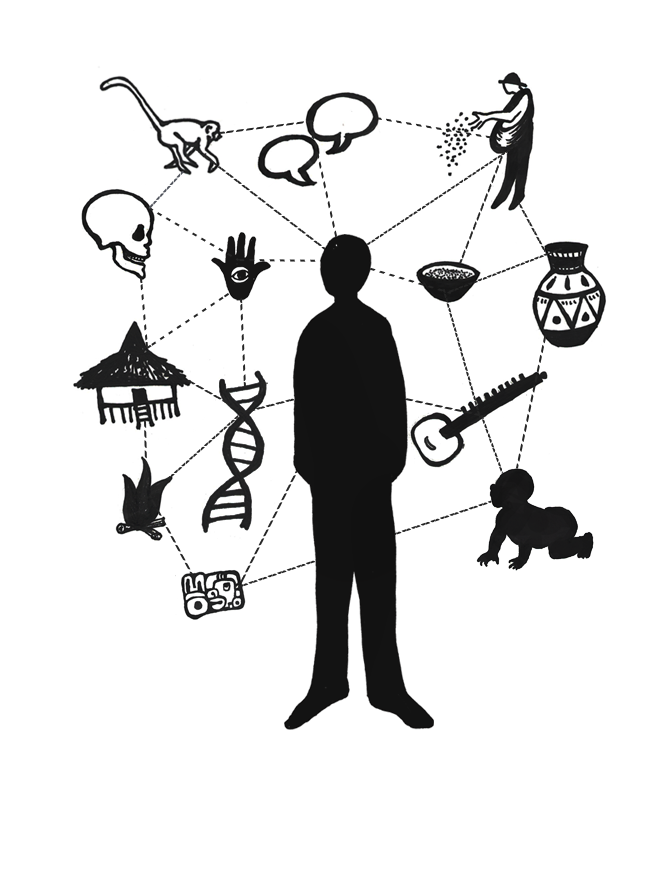

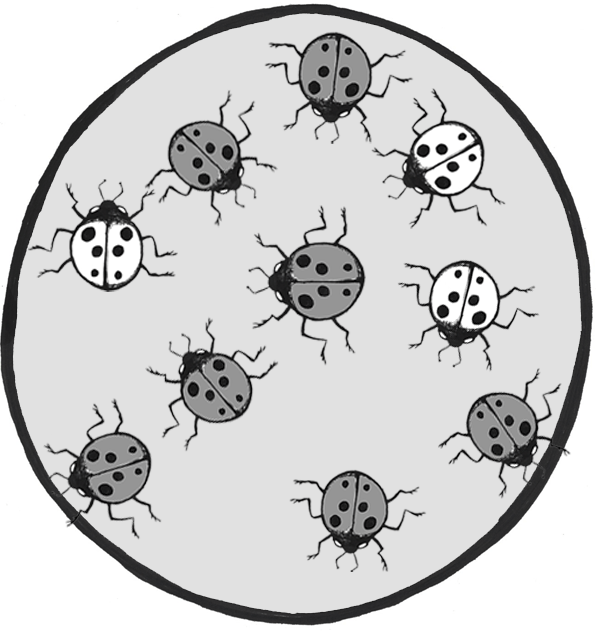

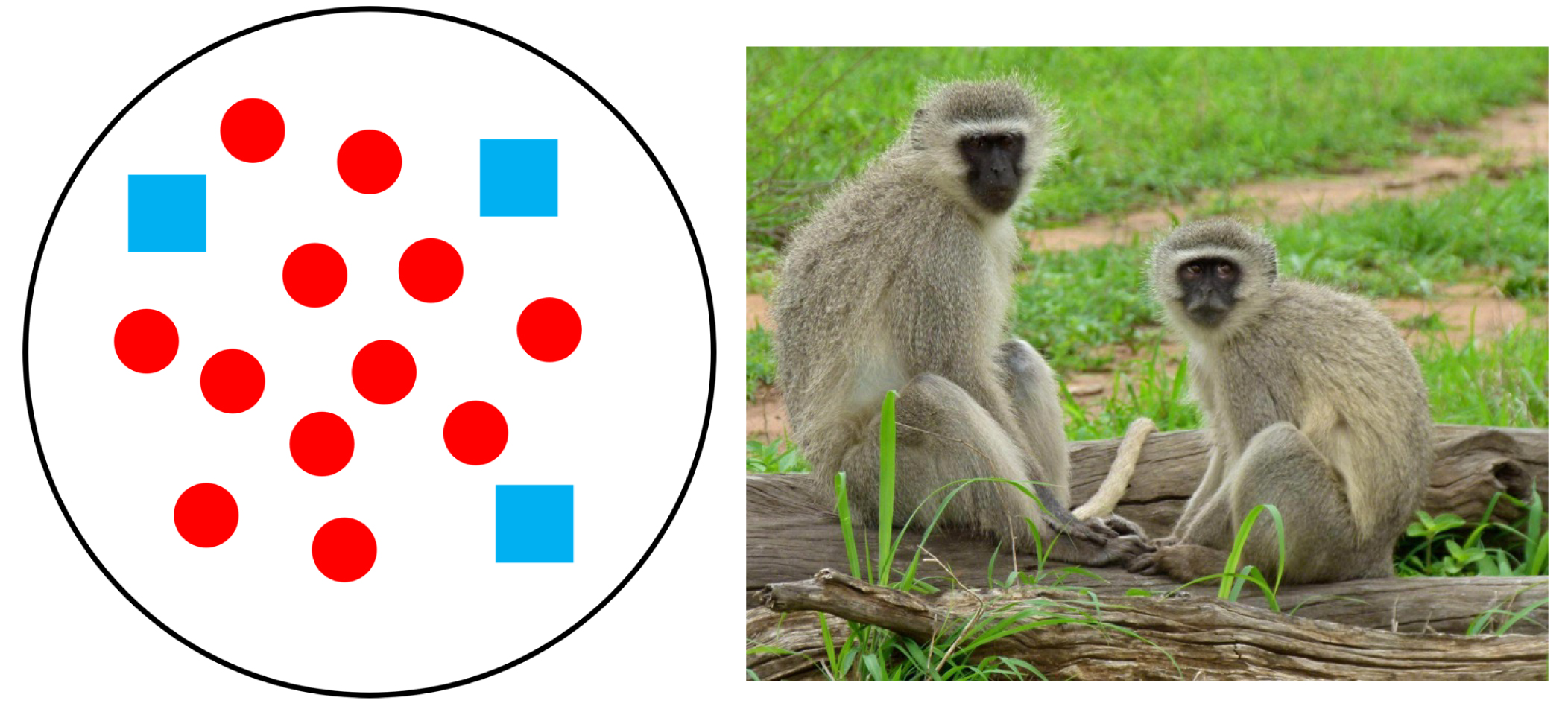

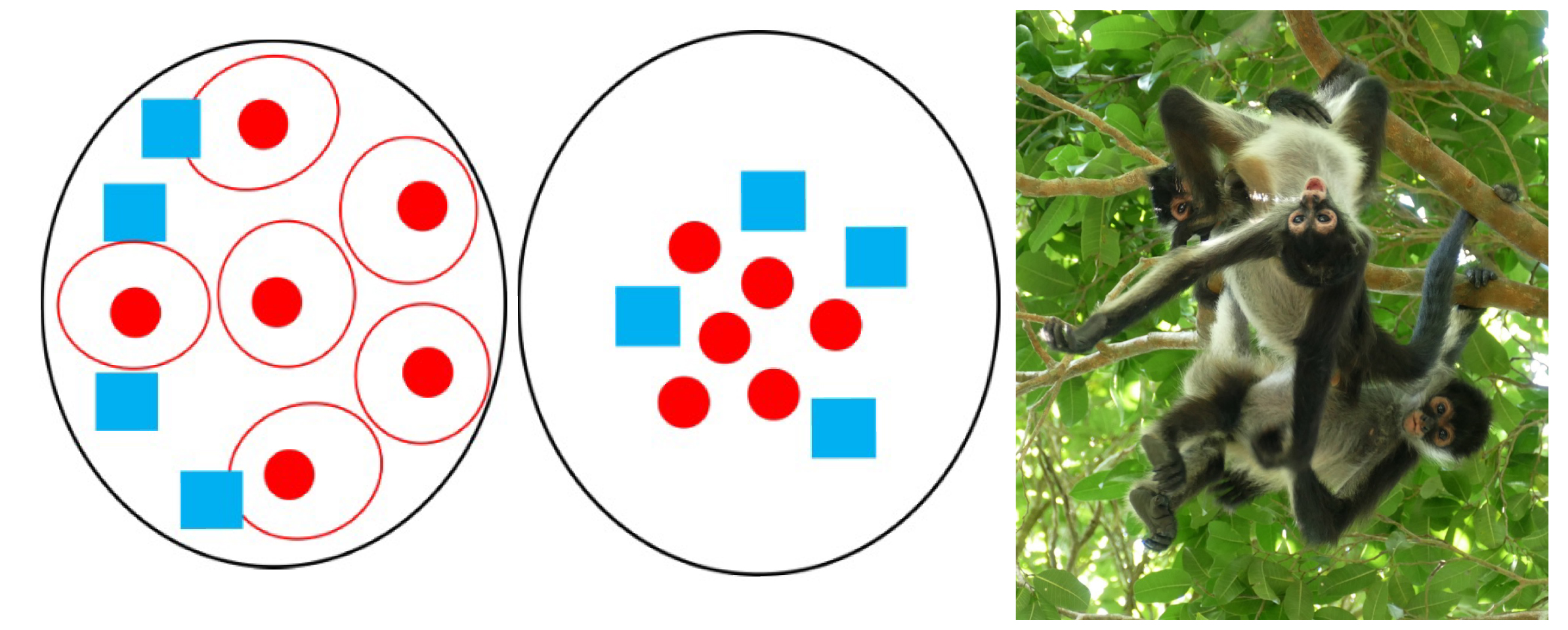

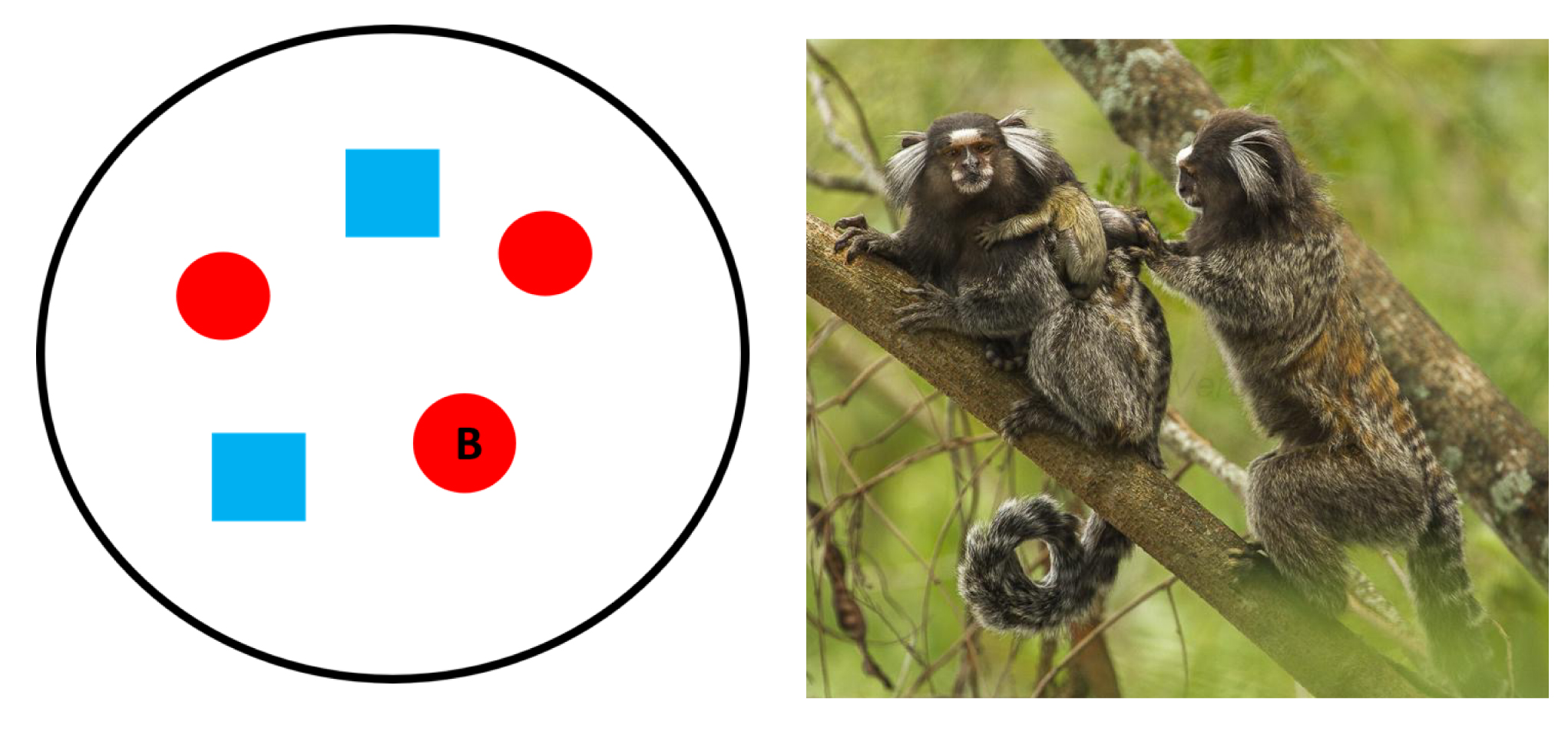

Holism

Anthropologists are interested in the whole of humanity. We look at the interactions among several aspects of our complex bodies or societies, rather than focusing on a singular aspect (Figure 1.8). For example, a biological anthropologist studying the social behaviors of a monkey species in South America may not only observe how they interact with one another, but also how physical adaptations, foraging patterns, ecological conditions, and habitat changes also affect their behaviors. By focusing on only one factor, the anthropologist would attain an incomplete understanding of the species’ social life. A cultural anthropologist studying marriage in a small village in India would not only consider local gender norms but also family networks, laws regarding marriage, religious rules, and economic factors. All of these aspects can influence marital practices in a given context. In both examples, the anthropologist is using a holistic approach by considering the multiple interrelated and intersecting factors that comprise a given phenomena.

Comparison

Anthropologists use comparative approaches to compare and contrast data from different populations, from groups within a population, or from the same group over time. For example: How do humans today differ from prior Homo sapiens populations? How does Egyptian society today compare to ancient Egyptian society? How do male and female behaviors differ within a given human society or a particular primate group? Comparative analyses help us understand commonalities and differences within or across species, groups, or time.

Dynamism

Comparative analysis is facilitated by the fact that humans are extremely dynamic. Our ability to change, both biologically and culturally, has enabled us to persist over millions of years and to thrive in different environments. Anthropologists ask about all kinds of changes: short-term and long-term, temporary and permanent, cultural and biological. For example, a cultural anthropologist might look at how people in a relatively isolated society are affected by globalization. A linguistic anthropologist might explore how a hybrid form of language, like Spanglish, emerged. An archaeologist might study how climate change influenced the emergence of agriculture. A biological anthropologist might consider how diseases affecting our ancestors led to physical changes that persist today. All of these examples highlight the dynamic nature of human bodies and societies.

Fieldwork

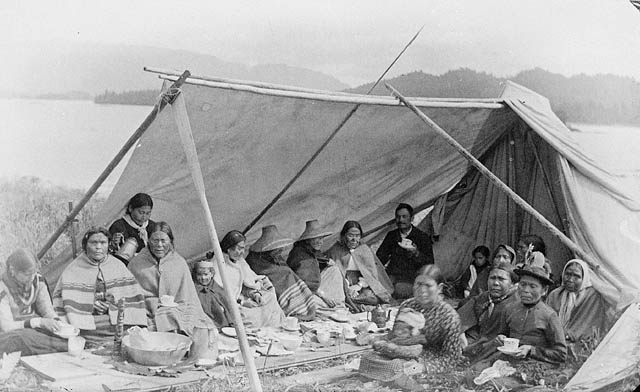

Throughout this book, you will read examples of anthropological research from around the world. Anthropologists do not only work in laboratories, libraries, or offices. To collect data, they travel to where their data lives, whether it is a city, village, cave, tropical forest, or desert. At their field sites, anthropologists collect data that, depending on subdiscipline, may include interviews with local peoples (Figure 1.9), examples of language in use, skeletal features, or cultural remains like stone tools. While anthropologists ask an array of questions and use diverse methods to answer their research questions, they share this commitment to conducting research in the field.

What is Biological Anthropology?

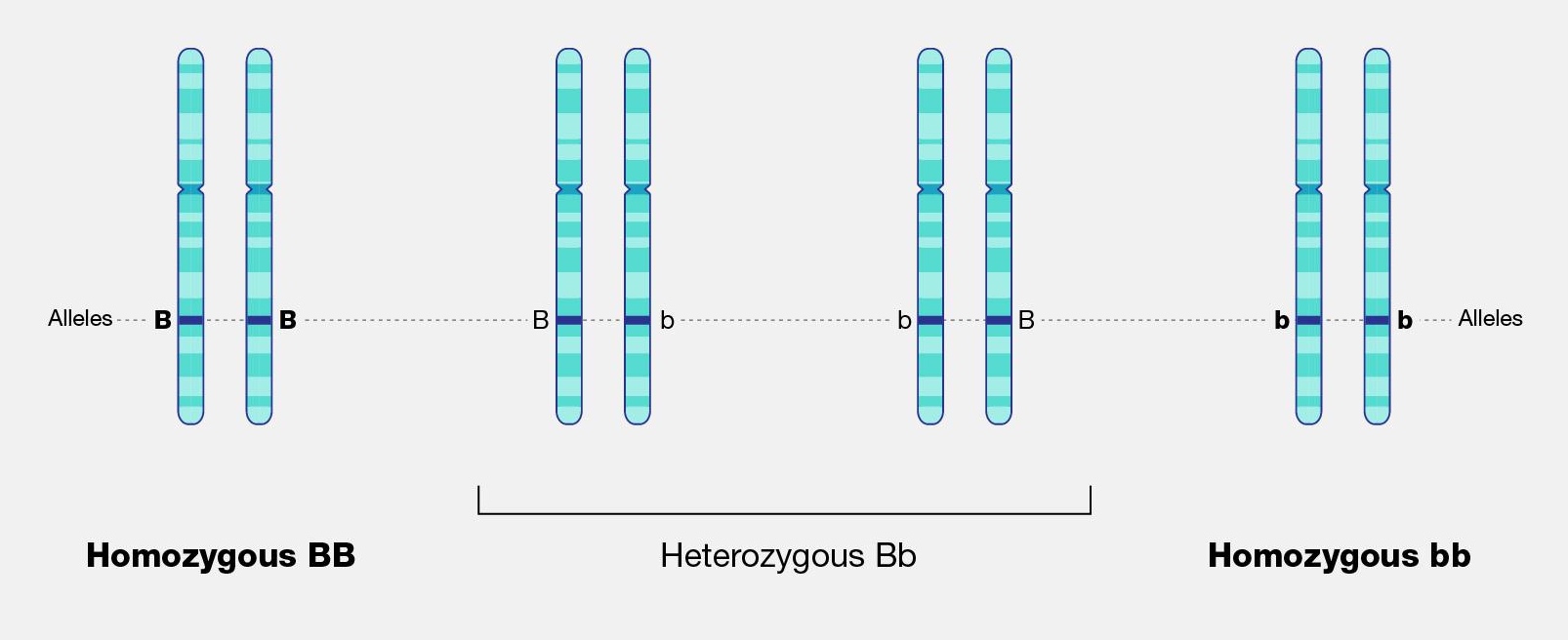

Biological anthropology uses a scientific and evolutionary approach to answer many of the same questions that all anthropologists are concerned with: What does it mean to be human? Where do we come from? Who are we today? Biological anthropologists are concerned with exploring how humans vary biologically, how humans adapt to their changing environments, and how humans have evolved over time and continue to evolve today. Some biological anthropologists also study what humans and nonhuman primates have in common and how we differ.

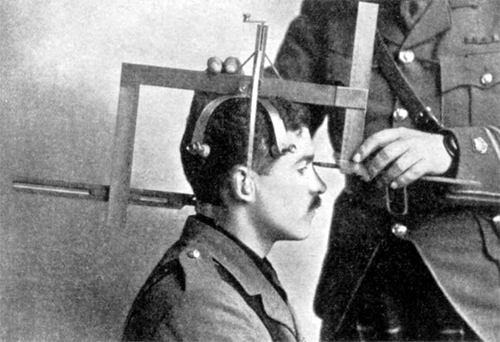

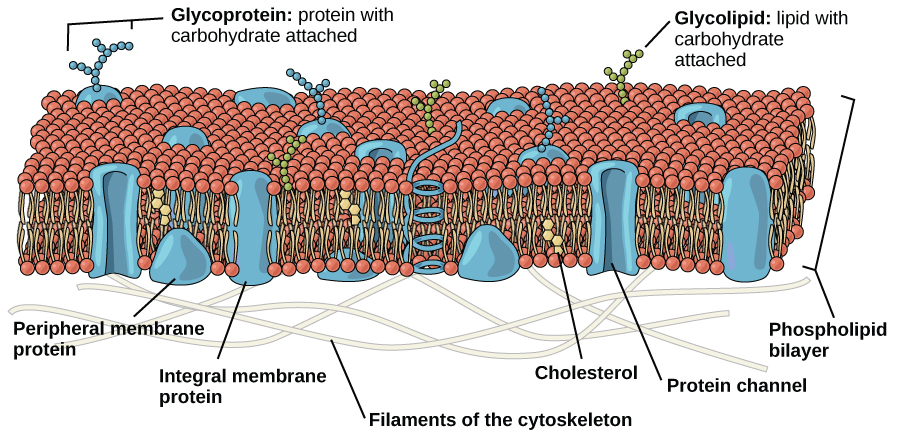

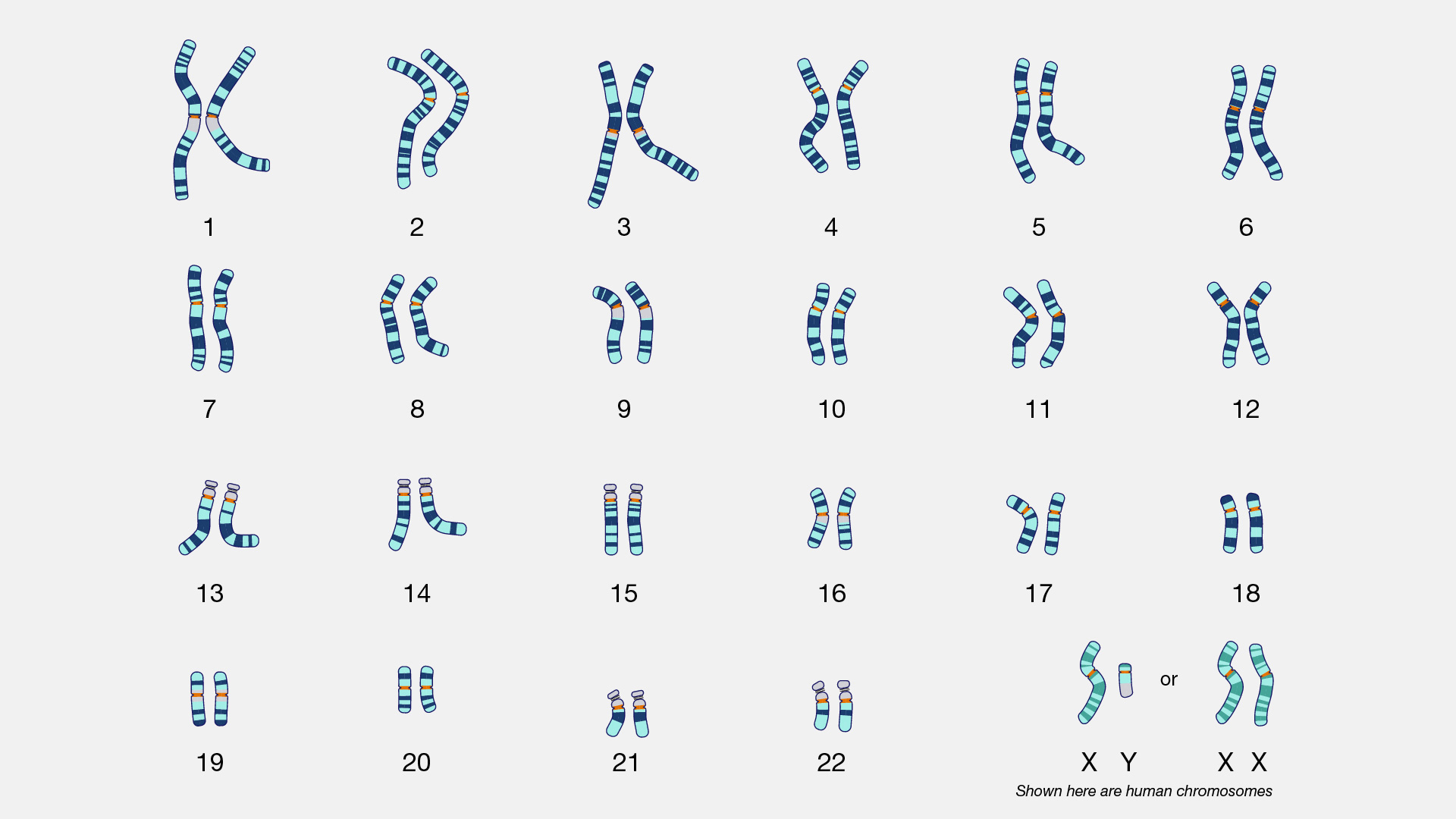

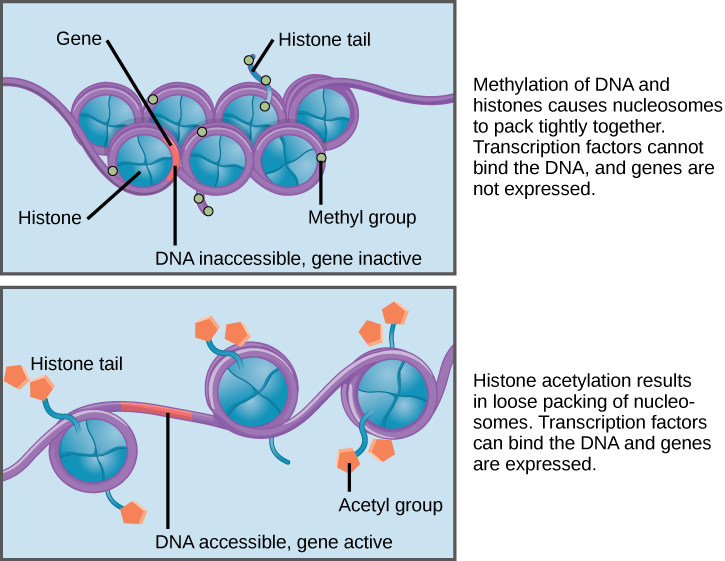

You may have heard biological anthropology referred to by another name—physical anthropology. Physical anthropology is a discipline that dates to as far back as the eighteenth century, when it focused mostly on physical variation among humans. Some early physical anthropologists were also physicians or anatomists interested in comparing and contrasting the human form. These researchers dedicated themselves to measuring bodies and skulls (anthropometry and craniometry) in great detail (Figure 1.10). Many also acted under the misguided racist belief that human biological races existed and that it was possible to differentiate between, or even rank, such races by measuring differences in human anatomy. Anthropologists today agree that there are no biological human races and that all humans alive today are members of the same species, Homo sapiens, and subspecies, Homo sapiens sapiens. We recognize that the differences we can see between peoples’ bodies are due to a wide variety of factors, including environment, diet, activities, and genetic makeup.

The subdiscipline has changed a great deal since these early years. Biological anthropologists no longer identify human differences in order to assign people to groups, like races. The focus is instead on understanding how and why human and primate variation developed through evolutionary processes. The name for the subdiscipline has transitioned in recent years (from physical anthropology to biological anthropology) to reflect these changes. Many believe the term biological anthropology better reflects the subdiscipline’s focus today, which includes genetic and molecular research.

The Scope of Biological Anthropology

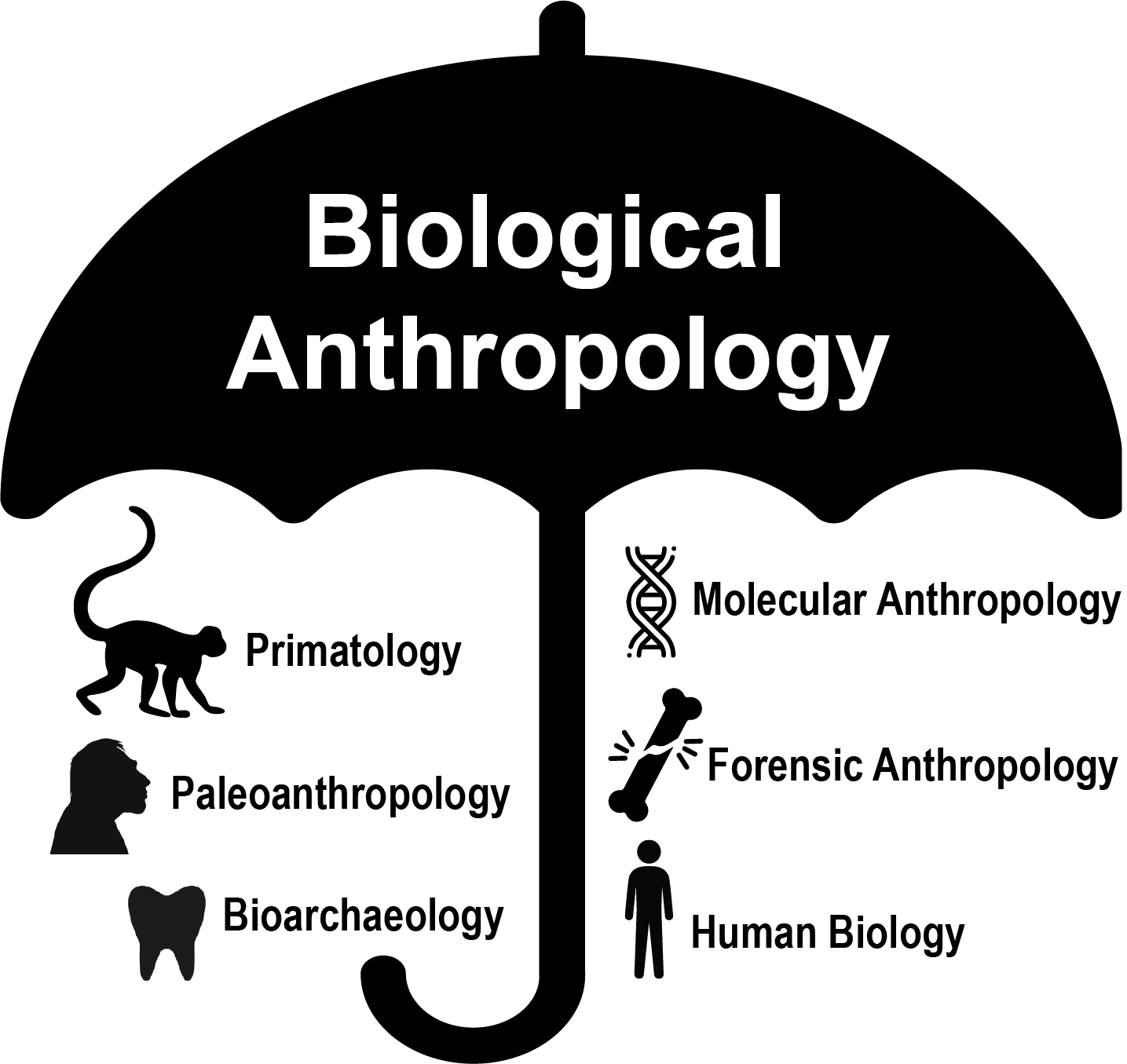

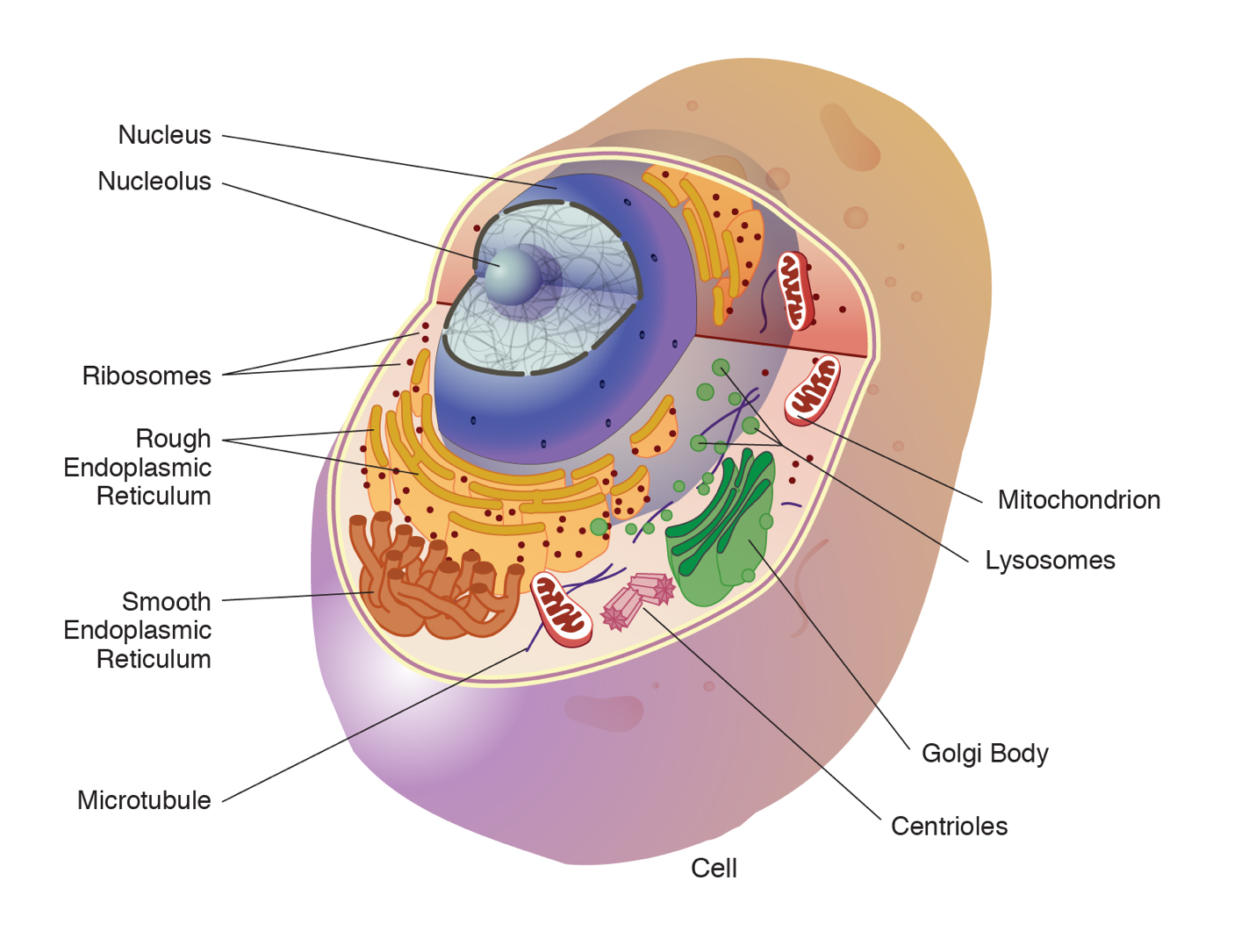

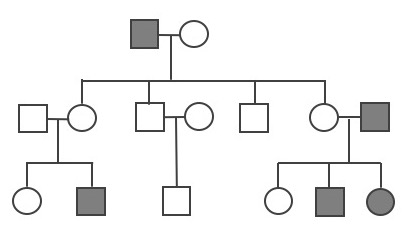

Just as anthropology as a discipline is wide ranging and holistic, so too is the subdiscipline of biological anthropology. There are at least six subfields within biological anthropology (Figure 1.11): primatology, paleoanthropology, molecular anthropology, bioarchaeology, forensic anthropology, and human biology. Each subfield focuses on a different dimension of what it means to be human from a biological perspective. Through their varied research in these subfields, biological anthropologists try to answer the following key questions:

- What is our place in nature? How are we related to other organisms? What makes us unique?

- What are our origins? What influenced our evolution?

- How and when did we move/migrate across the globe?

- How are humans around the world today different from and similar to each other? What influences these patterns of variation? What are the patterns of our recent evolution and how do we continue to evolve?

The terms subfield and subdiscipline are very similar and are often used interchangeably. In this book we use subdiscipline to refer to the four major areas of focus that make up the discipline of anthropology: biological anthropology, cultural anthropology, archaeological anthropology, and linguistic anthropology. When we use the term subfield we are referring to the different specializations within biological anthropology.

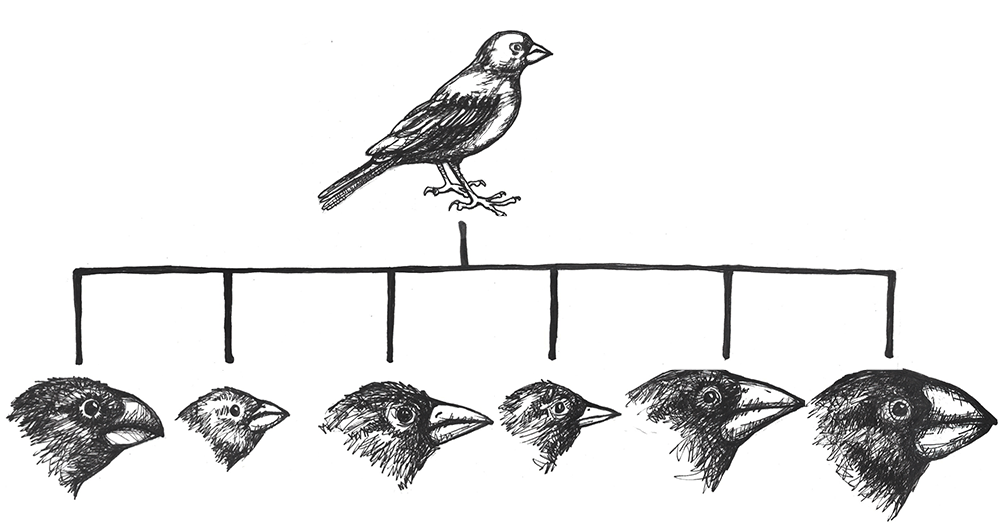

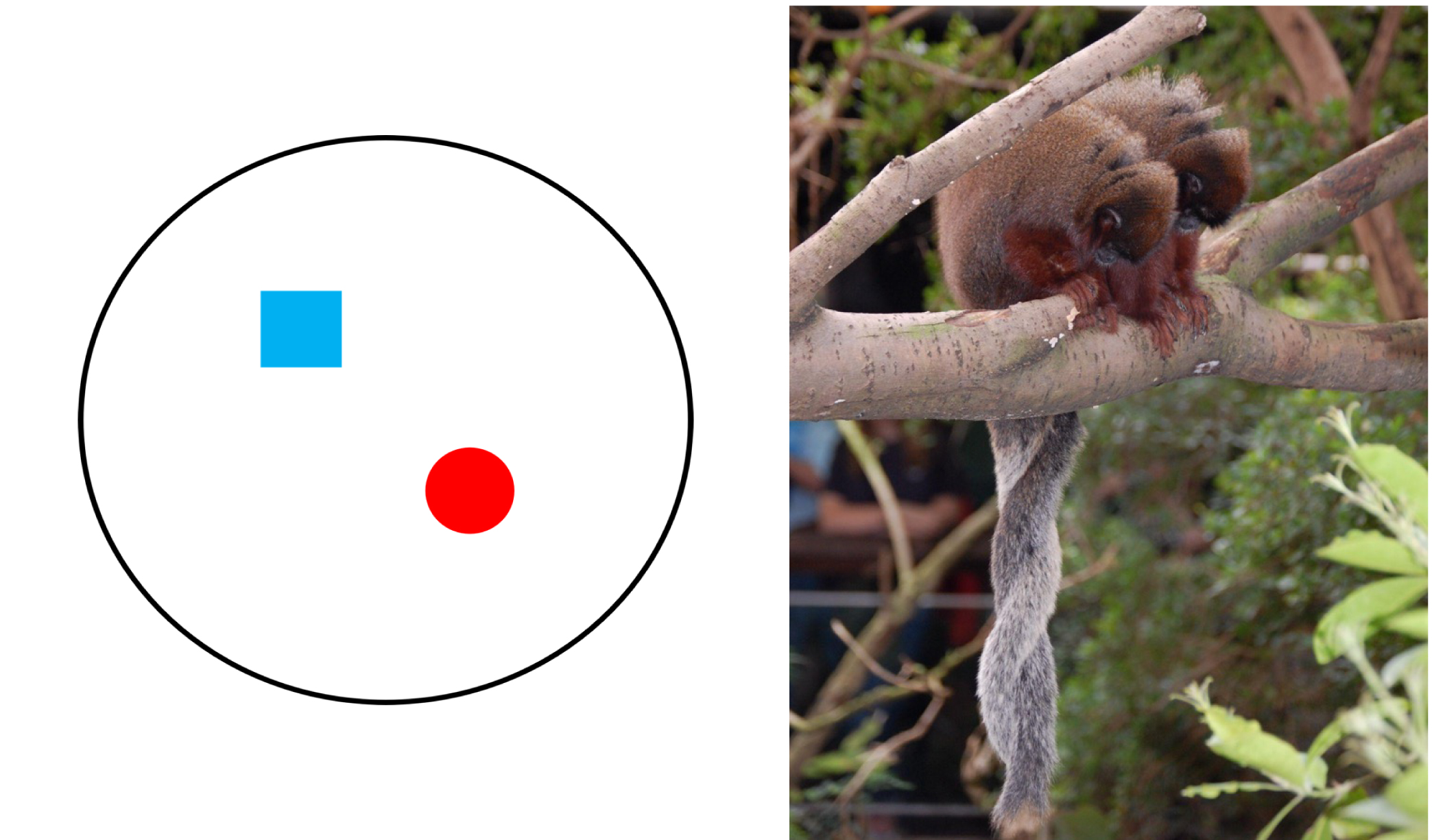

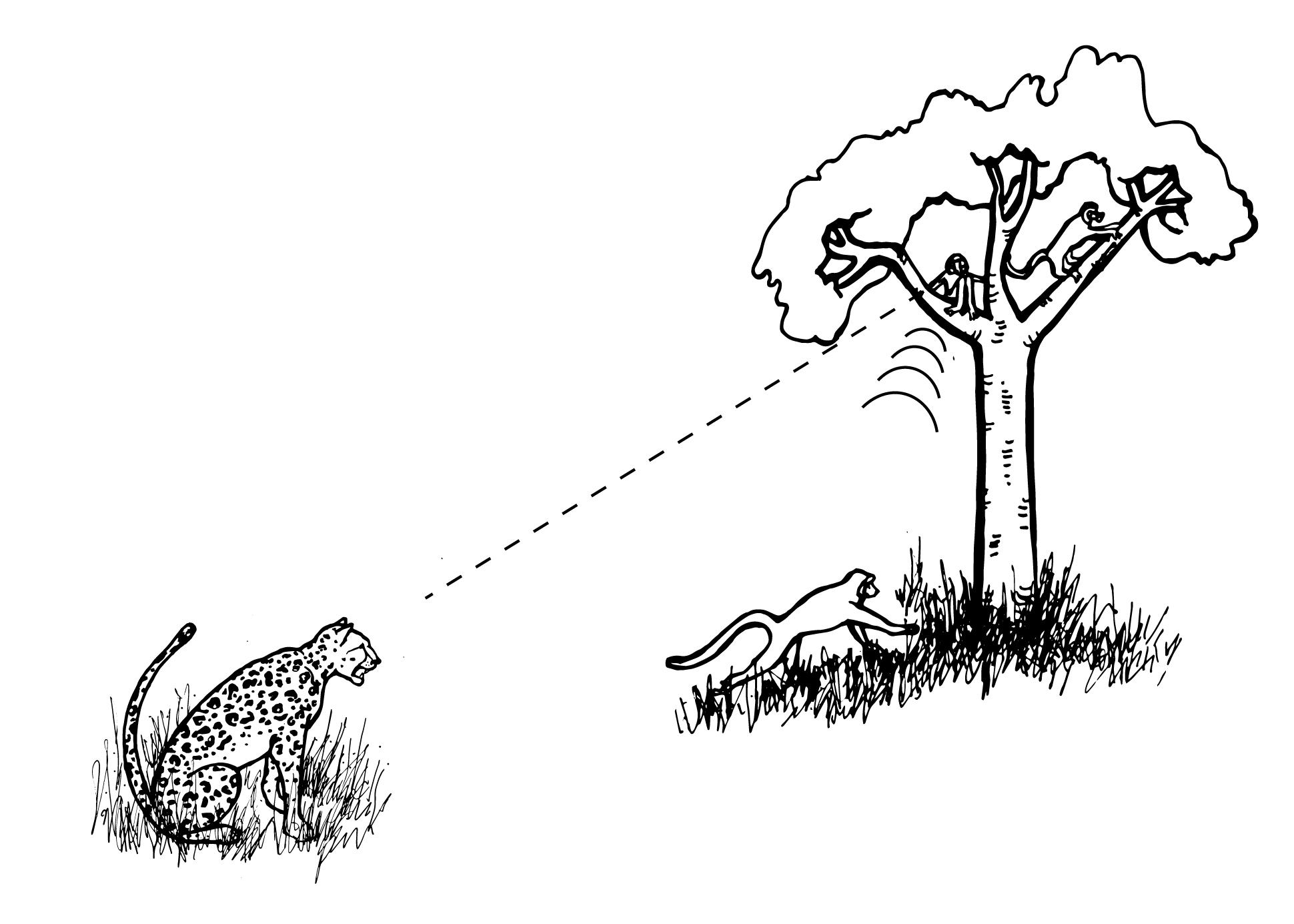

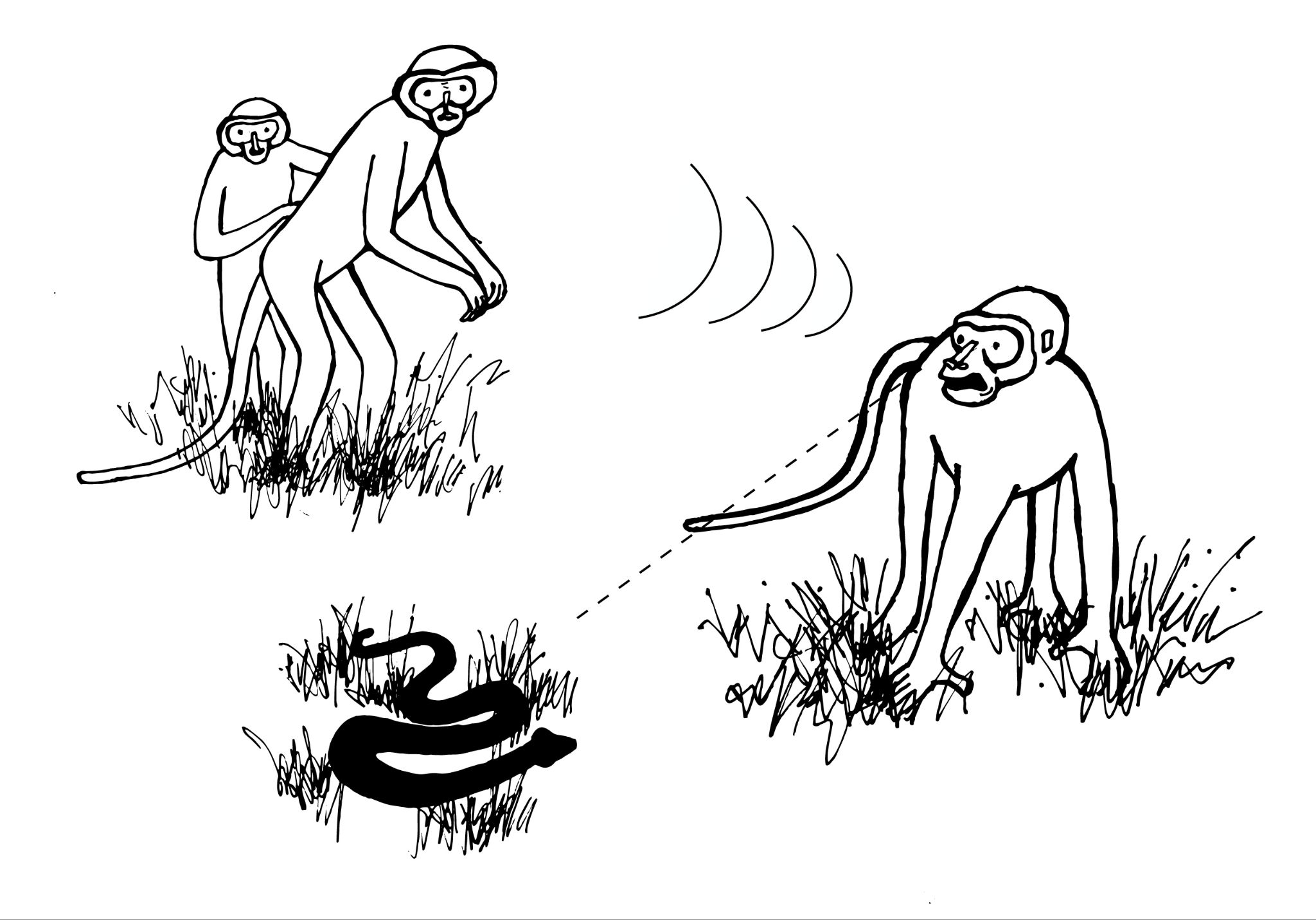

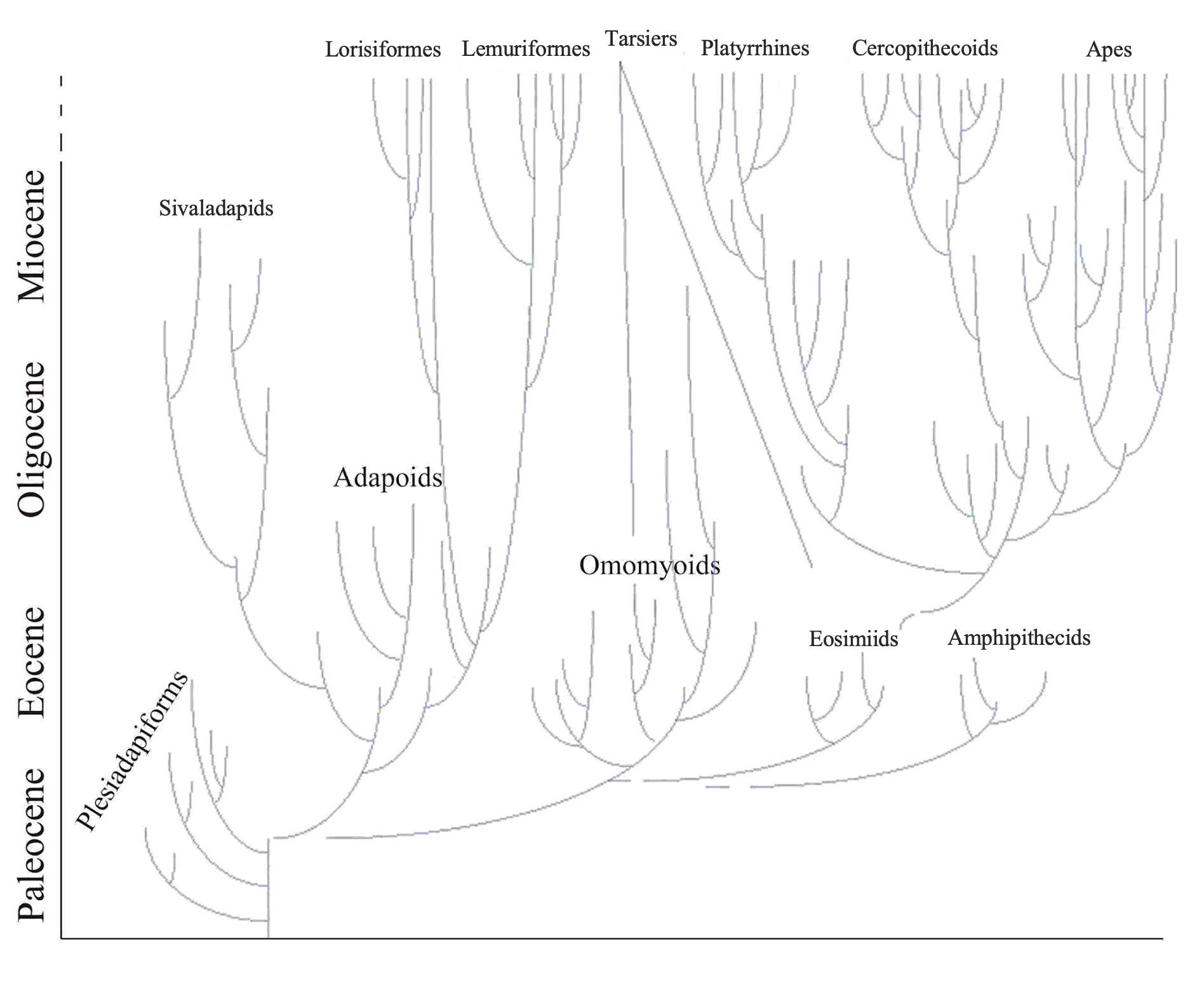

Primatology

Primatologists study the anatomy, behavior, ecology, and genetics of living and extinct nonhuman primates, including apes, monkeys, tarsiers, lemurs, and lorises. Primatology research gives us insights into how evolution has shaped our species, since nonhuman primates are our closest living biological relatives. Through such studies, we have learned that all primates share a suite of traits. Primates, for instance, have nails instead of claws, possess hands that can grasp and manipulate objects (Figure 1.12), invest great amounts of time and energy in raising a small number of offspring, and employ complex social behaviors. Behavioral studies, such as those by Jane Goodall of wild chimpanzees and others, reveal that great apes are like humans in that they have families and form strong maternal-infant relationships. Gorillas mourn the deaths of their group members, and they exhibit behaviors similar to humans such as playing and tickling. Importantly, the work of Goodall, Karen B. Strier (see Appendix B), and others focus on primate conservation: They have brought attention to the fact that 60% of primates are currently threatened with extinction (Estrada et al. 2017).

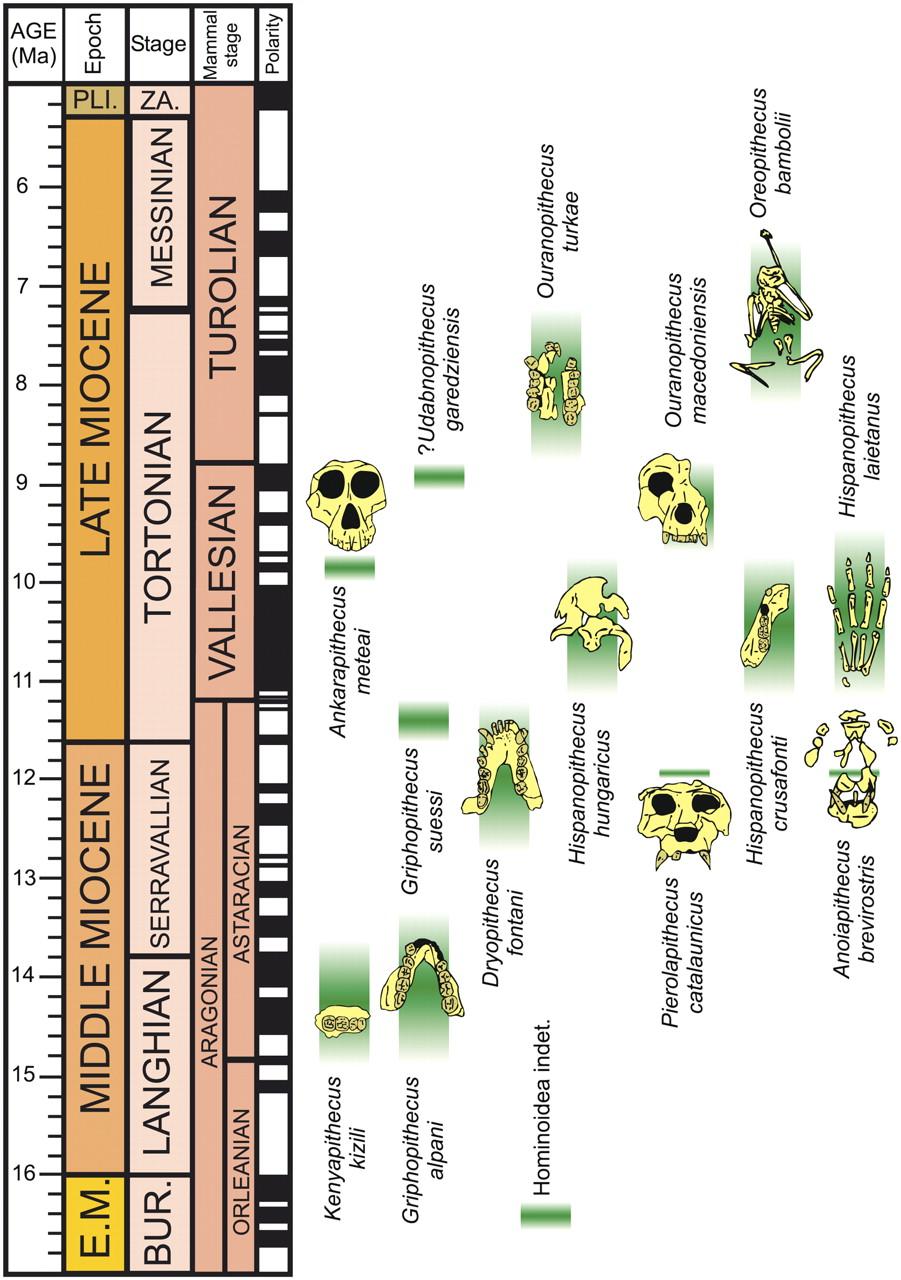

Paleoanthropology

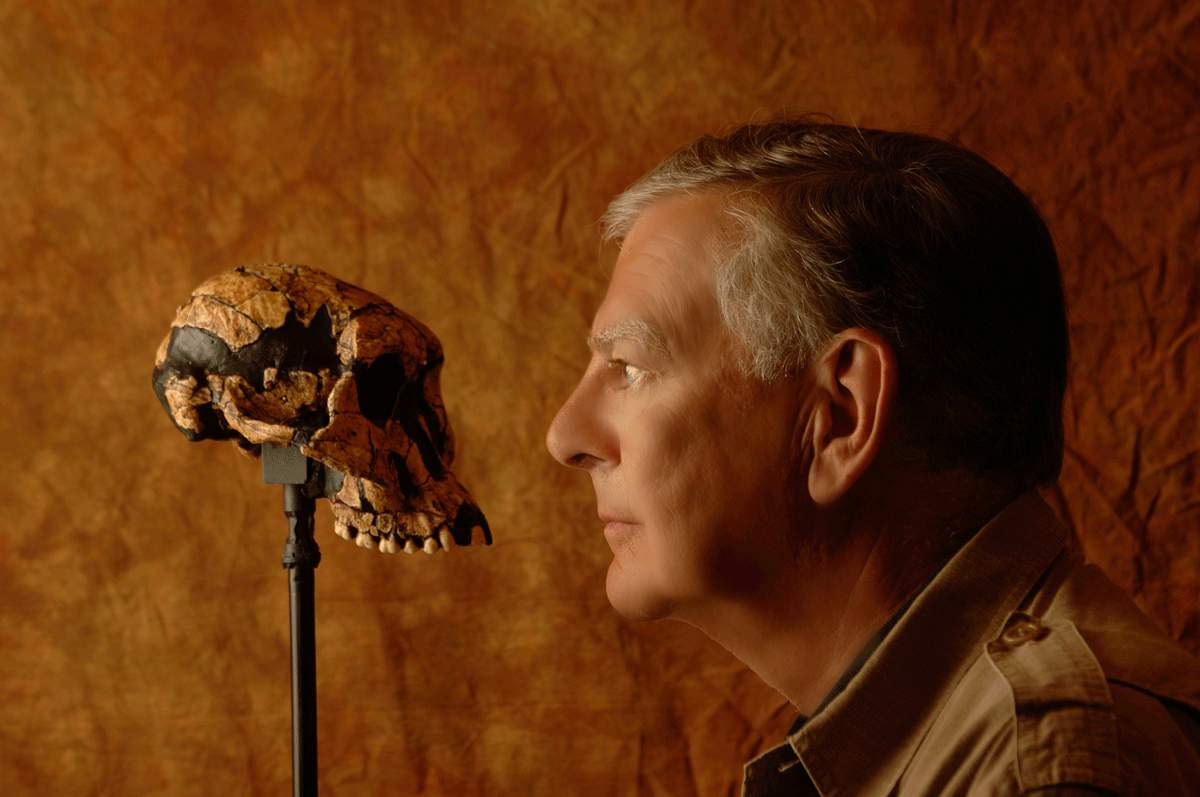

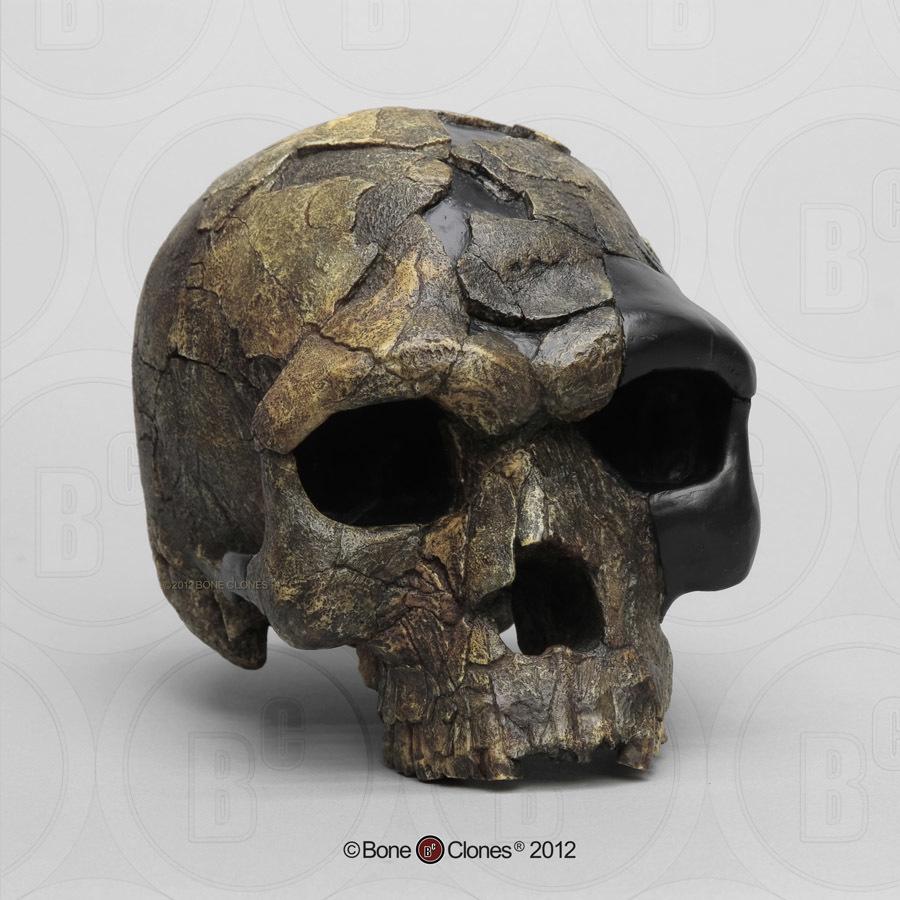

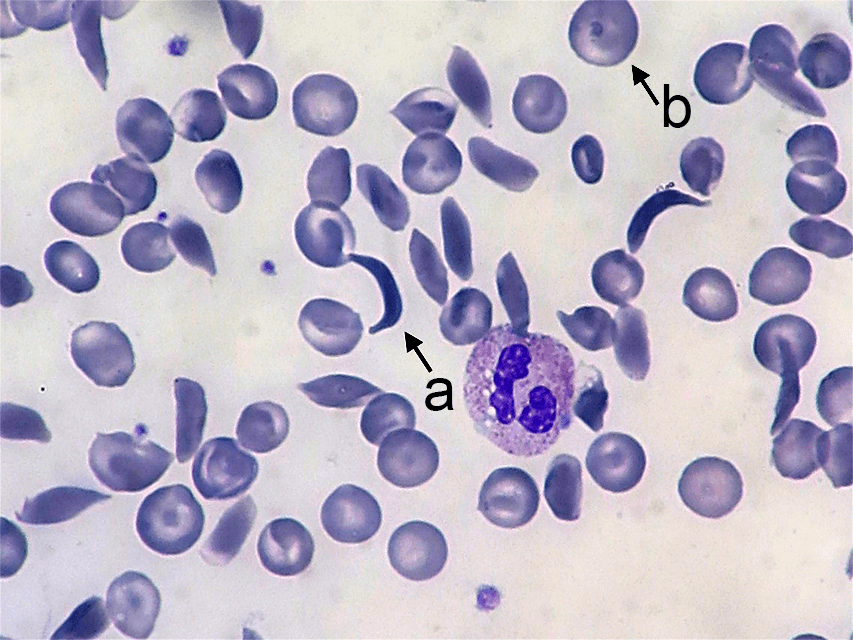

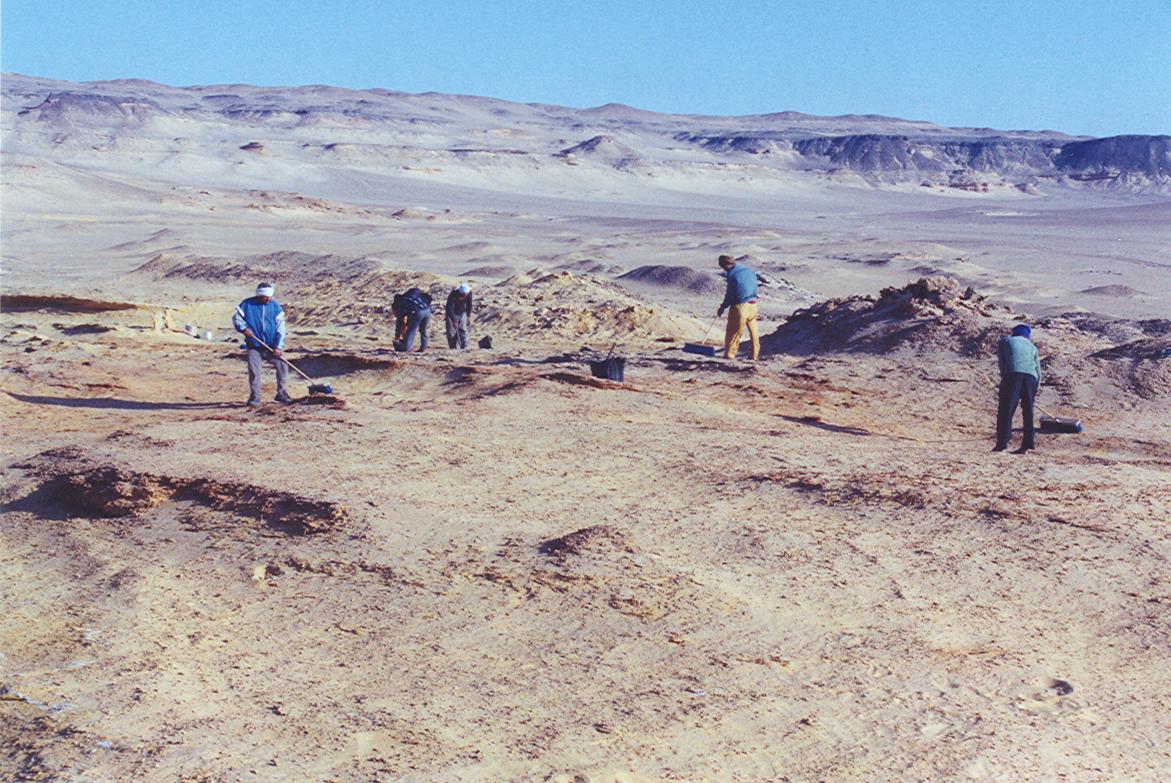

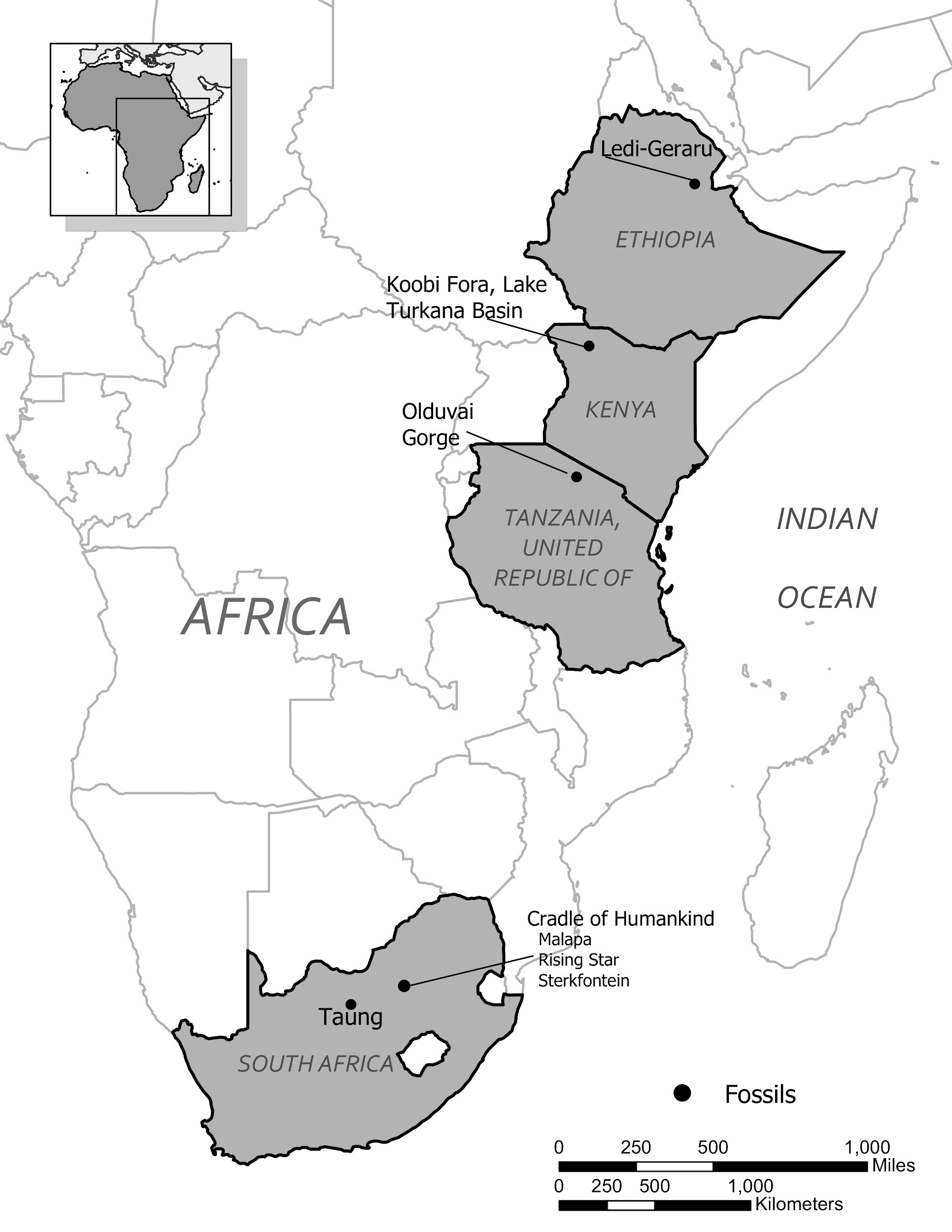

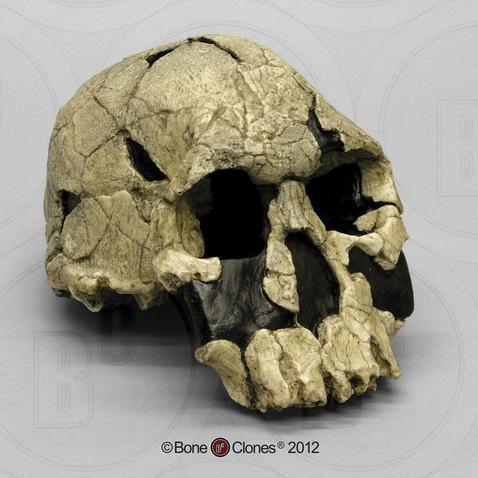

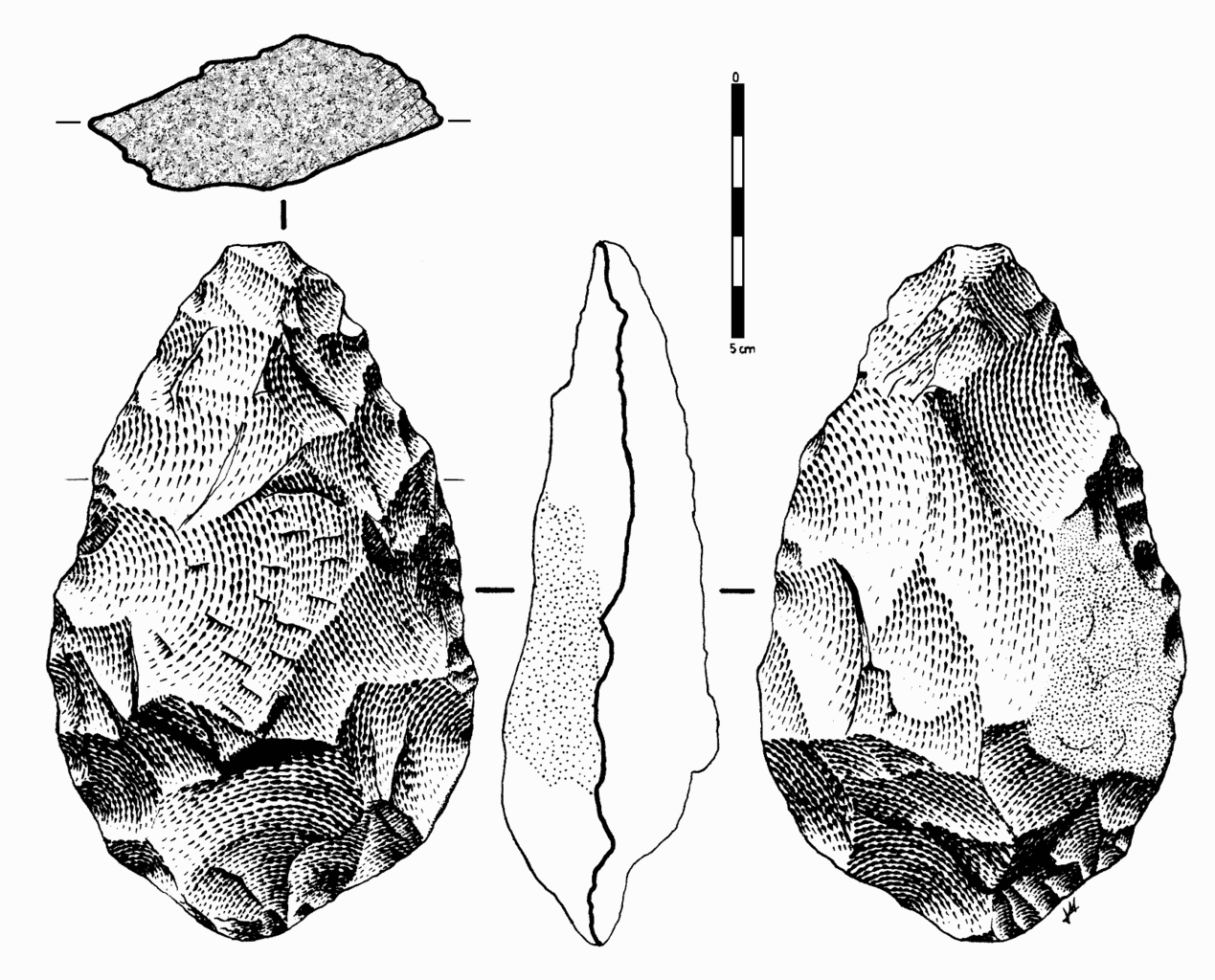

Paleoanthropologists study human ancestors from the distant past to learn how, why, and where they evolved. Because these ancestors lived before there were written records, paleoanthropologists have to rely on various types of physical evidence to come to their conclusions. This evidence includes fossilized remains (particularly fossilized bones; Figure 1.13), DNA, artifacts such as stone tools, and the contexts in which these items are found. In recent years, paleoanthropologists have made some monumental discoveries about hominin evolution.

These findings helped us learn that human evolution did not occur in a simple, straight line but, rather, branched out in many directions. Most branches were evolutionary “dead ends.” Humans are now the only living hominins left on planet Earth. Paleoanthropologists frequently work together with other scientists such as archaeologists, geologists, and paleontologists to interpret and understand the evidence they find. Paleoanthropology is a dynamic subfield of biological anthropology that contributes to our understanding of human origins and evolution.

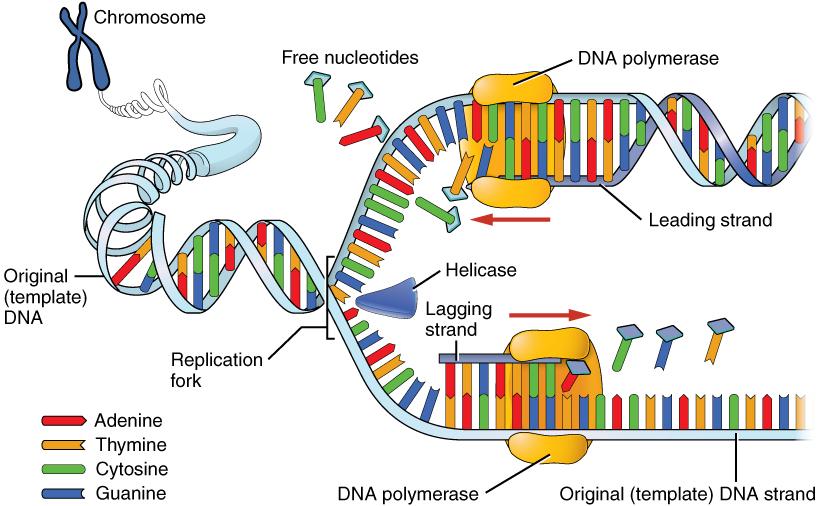

Molecular Anthropology

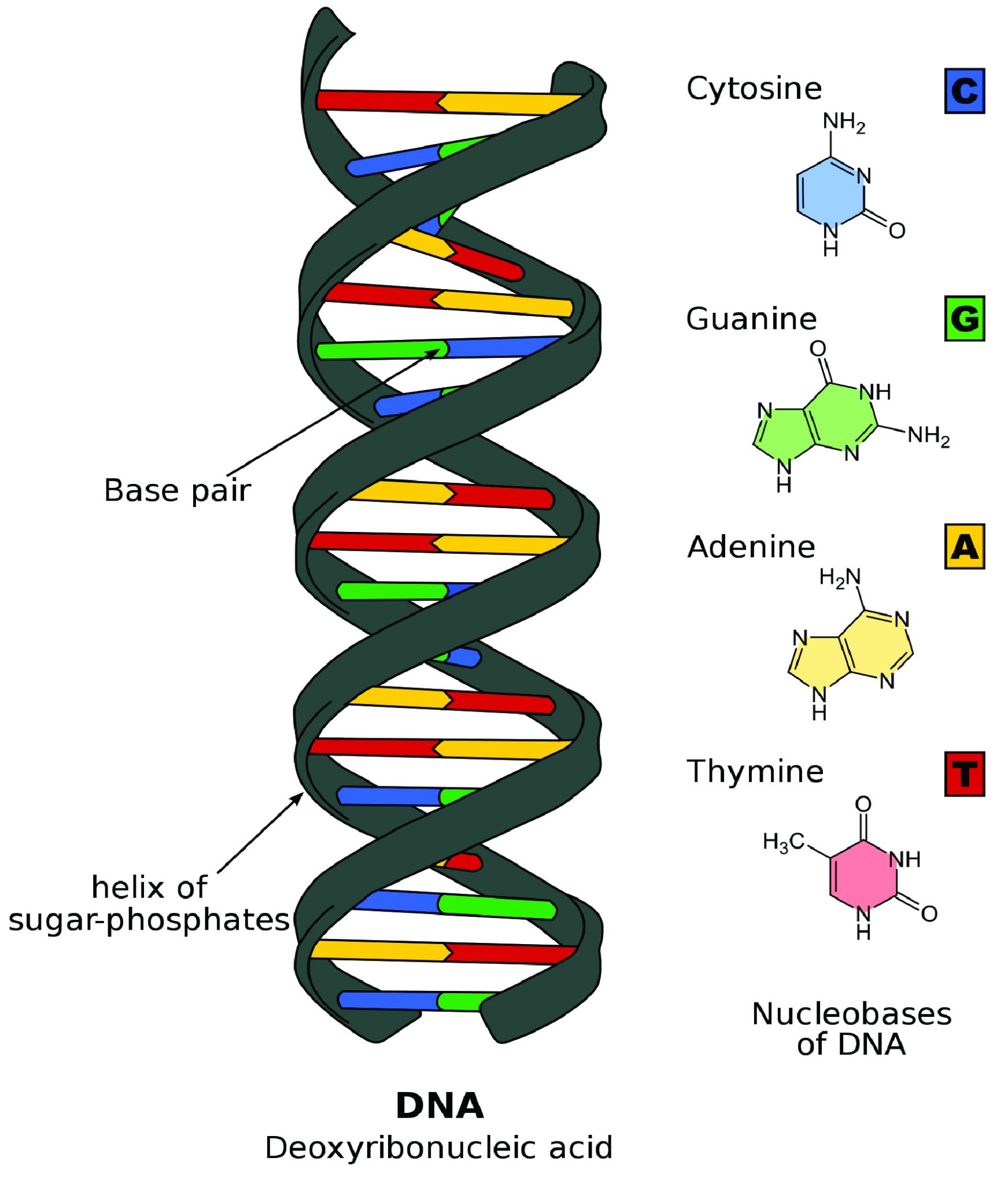

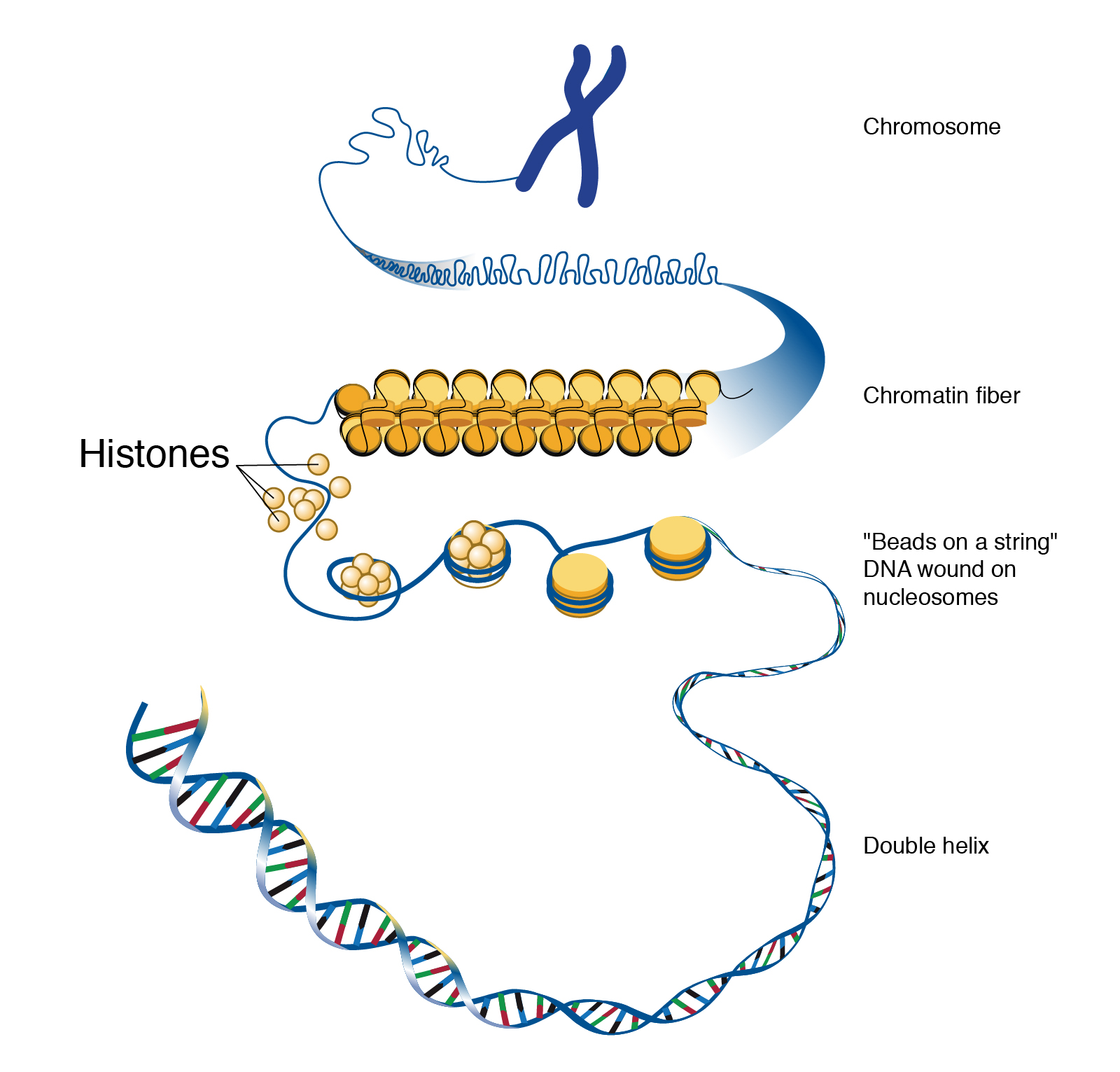

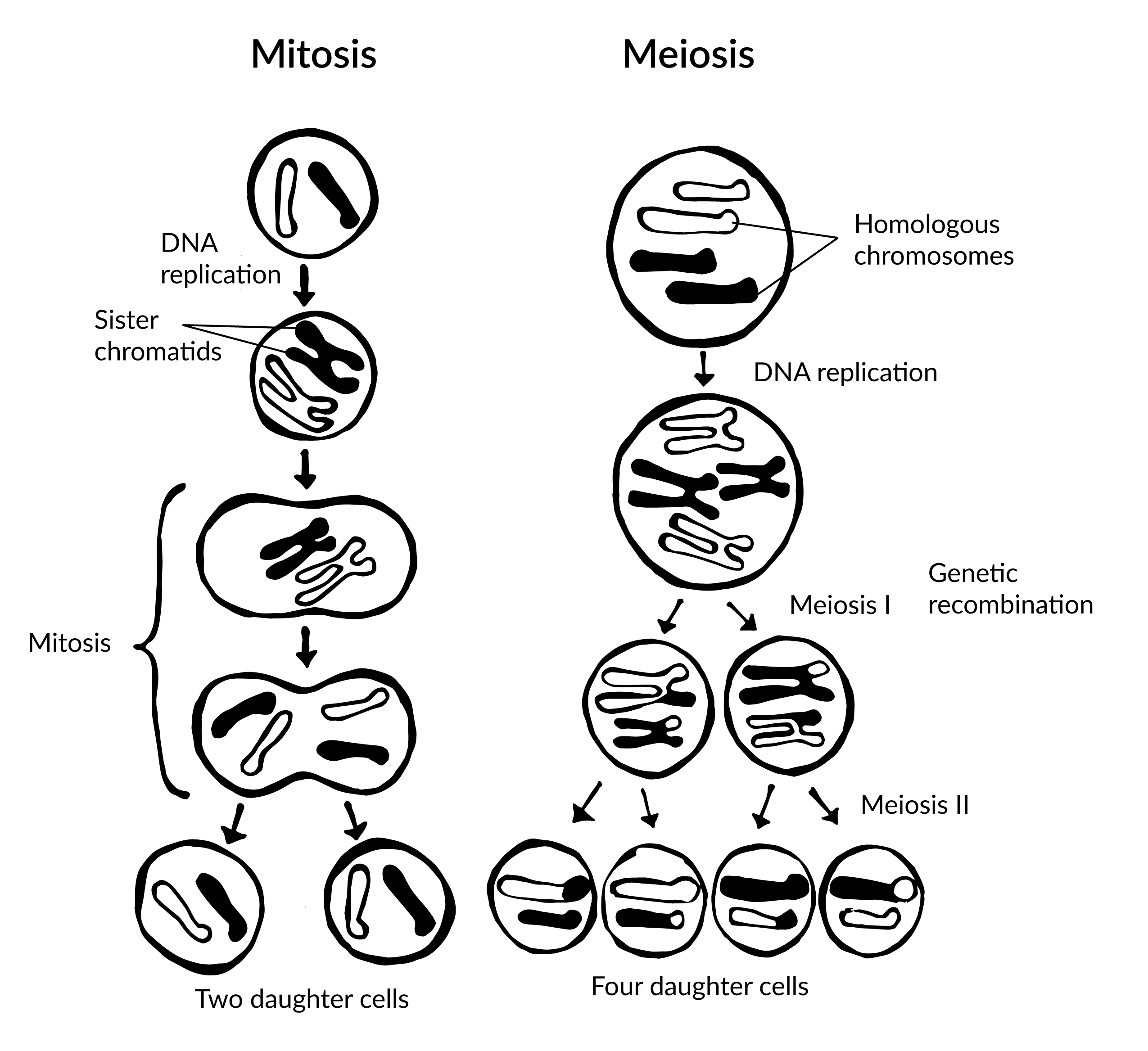

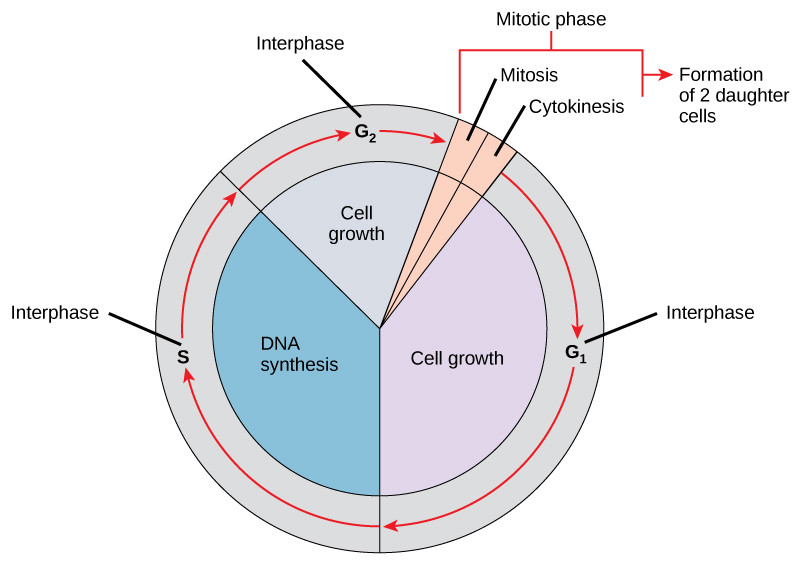

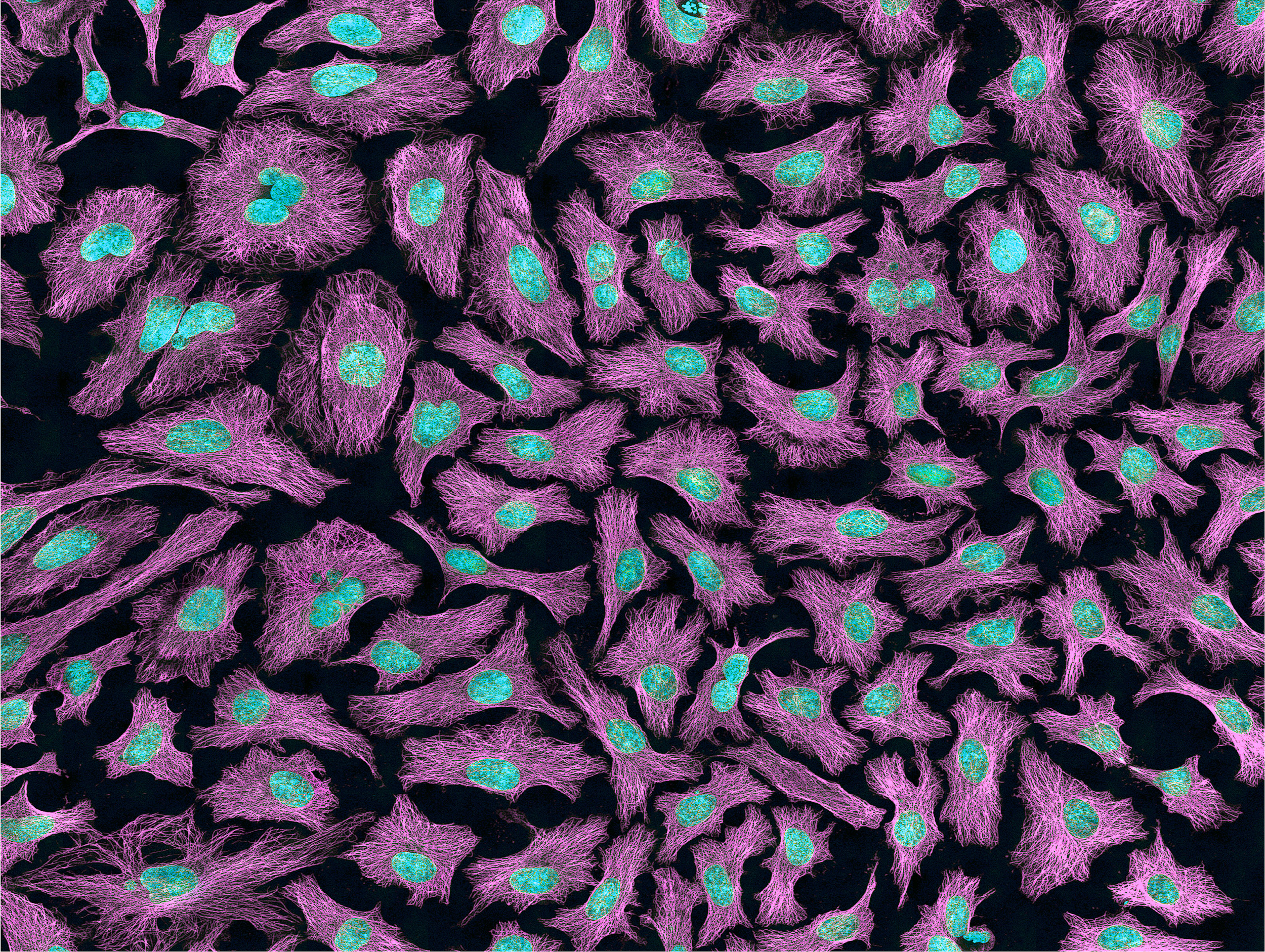

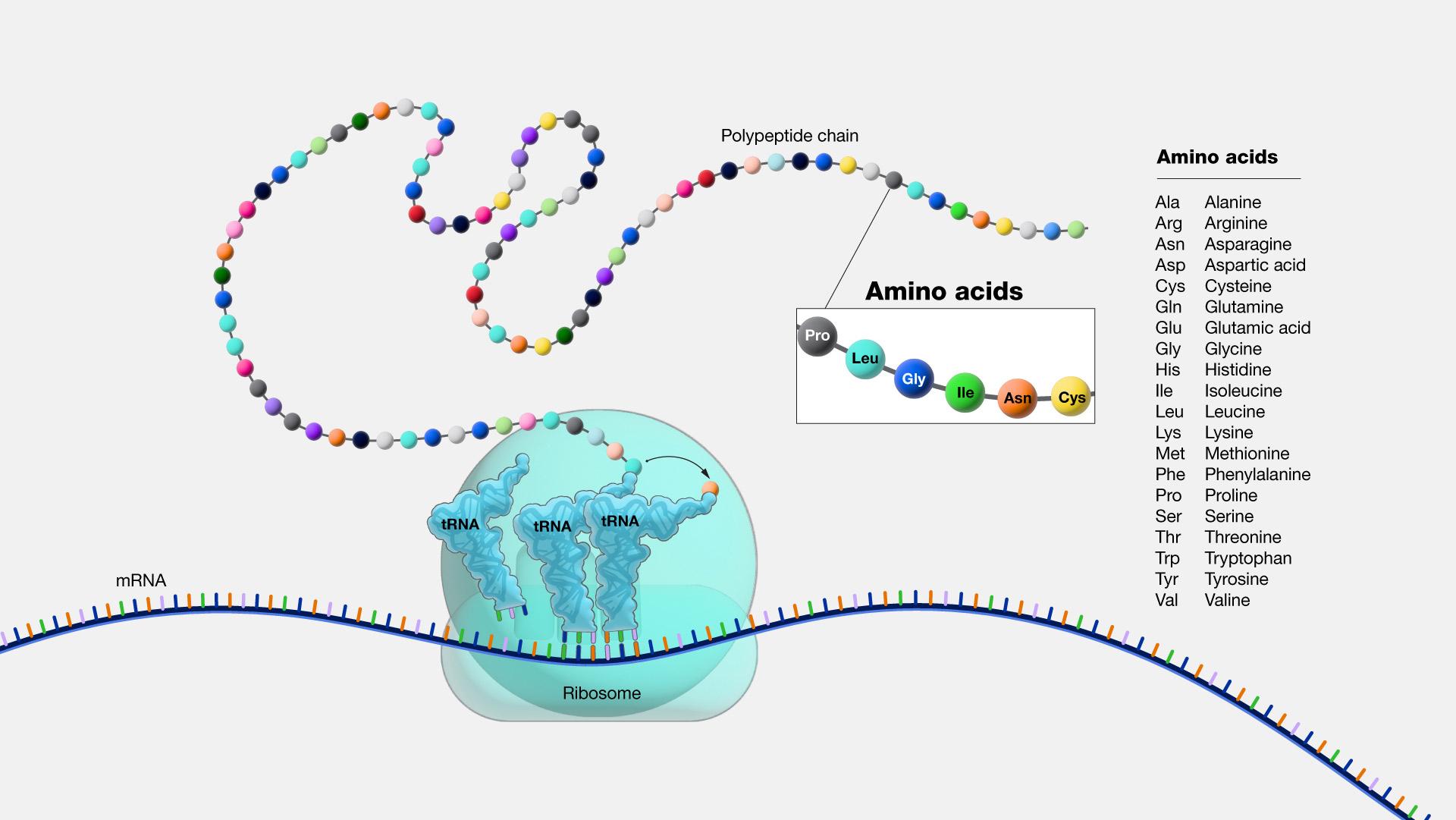

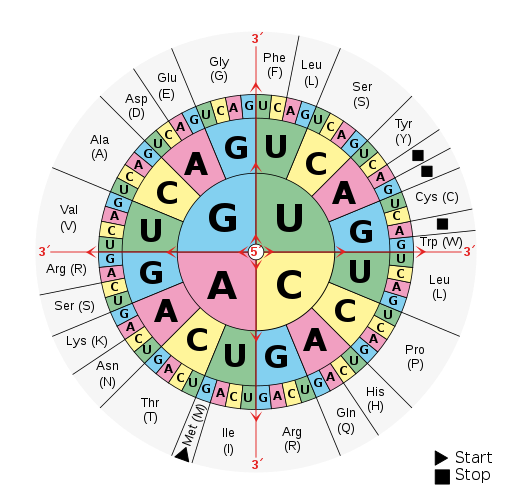

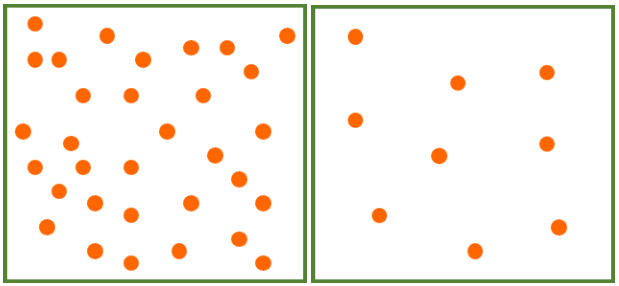

Molecular anthropologists use molecular techniques (primarily genetics) to compare ancient and modern populations as well as to study living populations of humans or nonhuman primates. By examining DNA sequences, molecular anthropologists can estimate how closely related two populations are, as well as identify population events, like a population decline, that explain the observed genetic patterns. This information helps scientists trace patterns of migration and identify how people have adapted to different environments over time.

Several molecular anthropologists have recently attracted international recognition for their groundbreaking work. For instance, in 2022, Svante Pääbo won the Nobel Prize in physiology (medicine) for his work extracting the DNA from 40,000-year-old Neanderthal bones and producing the first complete genome of Homo neanderthalensis. This was a challenging task because ancient DNA does not preserve well and older extraction techniques tended to become contaminated by the researcher’s and other environmental DNA. Pääbo and his team designed specialized clean rooms for handling ancient DNA and made advances in DNA sequencing. Their research helped scientists identify genetic differences between modern humans and Neanderthals and analyze how those differences influence how diseases, such as COVID-19, affect our bodies. Molecular anthropology is a quickly changing field as new techniques and discoveries shape our understanding of ourselves, our ancestors, and our nonhuman primate relatives.

Bioarchaeology

Bioarchaeologists study human skeletal remains along with the surrounding soils and other materials. They use the research methods of skeletal biology, mortuary studies, osteology, and archaeology to answer questions about the lifeways of past populations. Through studying the bones and burials of past peoples, bioarchaeologists search for answers to how people lived and died, including their health, nutrition, diseases, and/or injuries. Most bioarchaeologists study not just individuals but entire populations to reveal biological and cultural patterns.

People have always been intrigued by the remains of the dead, however historically, human bodies were often studied isolated from the ground and location where they were found. Bioarchaeologists emphasize the context in and around where the remains are found, using a biocultural approach that studies humans through an understanding of the interconnectedness of biology, culture, and environment.

Forensic Anthropology

Forensic anthropologists use many of the same techniques as bioarchaeologists to develop a biological profile for unidentified individuals, including estimating sex, age at death, height, ancestry, or other unique identifying features such as skeletal trauma or diseases. They may also go to a crime or accident scene to assist in the search and recovery of human remains, aiding law enforcement teams (Figure 1.14). The popular television show Bones told the fictional story of a forensic anthropologist, Dr. Temperance Brennan, who brilliantly interpreted clues from victims’ bones to help solve crimes. While the show includes forensic anthropology techniques and responsibilities, it also includes many inaccuracies. For example, forensic anthropologists do not collect trace evidence like hair or fibers, run DNA tests, carry weapons, or solve criminal cases.

Forensic anthropology is considered an applied area of biological anthropology, because it involves a practical application of anthropological theories, methods, and findings to solve real-world problems. While some forensic anthropologists are academics that work for colleges and universities, others are employed by public safety and law agencies.

Human Biology

Many biological anthropologists do work that falls under the label of “human biology.” This type of research explores how the human body is affected by different physical environments, cultural influences, and nutrition. These include studies of human variation or the physiological differences among humans around the world. Some of these anthropologists study human adaptations to extreme environments, which includes physiological responses and genetic advantages to help them survive. Others are interested in how nutrition and disease affect human growth and development. Biological anthropologists engage in a wide range of research that spans the breadth of human biological diversity.

The six subfields of biological anthropology—primatology, paleoanthropology, molecular anthropology, bioarchaeology, forensic anthropology, and human biology—all help us to understand what it means to be biologically human. From molecular analyses of our cells to studies of our changing skeleton, to research on our nonhuman primate cousins, biological anthropology assists in answering the central question of anthropology: What does it mean to be human? Despite their different foci, all biological anthropologists share a commitment to using a scientific approach to study how we became the complex, adaptable species we are today.

Key Terms

Belief: A firmly held opinion or conviction typically based on spiritual apprehension rather than empirical proof.

Cultural relativism: The anthropological practice of suspending judgment and seeking to understand another culture on its own terms sympathetically enough so that the culture appears to be a coherent and meaningful design for living.

Holism: The idea that the parts of a system interconnect and interact to make up the whole.

Hominins: Species that are regarded as human, directly ancestral to humans, or very closely related to humans.

Human adaptation: The ways in which human bodies, people, or cultures change, often in ways better suited to the environment or social context.

Human variation: The range of forms of any human characteristic, such as body shape or skin color.

Hypothesis: Explanation of observed facts; details how and why observed phenomena are the way they are. Scientific hypotheses rely on empirical evidence, are testable, and are able to be refuted.

Indigenous: Refers to people who are the original settlers of a given region and have deep ties to that place. Also known as First Peoples, Aboriginal Peoples, or Native Peoples, these populations are in contrast to other groups who have settled, occupied, or colonized the area more recently.

Law: A prediction about what will happen given certain conditions; typically mathematical.

Sapir-Whorf hypothesis: The principle that the language you speak allows you to think about some things and not other things. This is also known as the linguistic relativity hypothesis.

Subdisciplines: The four major areas that make up the discipline of anthropology: biological anthropology, cultural anthropology, archaeology, and linguistic anthropology. Applied anthropology is sometimes considered to be a fifth subdiscipline.

Subfield: In this textbook, subfield refers to the different specializations within biological anthropology, including primatology, paleoanthropology, molecular anthropology, bioarchaeology, forensic anthropology, and human biology.

For Further Exploration

American Anthropological Association website.

American Association of Biological Anthropologists website.

8, 2023

References

Binford, Leigh. 2016. The El Mozote Massacre: Human Rights and Global Implications. Revised and expanded edition. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Estrada, Alejandro, Paul A. Garber, Anthony B. Rylands, Christian Roos, Eduardo Fernandez-Duque, Anthony Di Fiore, K. Anne-Isola Nekaris, et al. 2017. “Impending Extinction Crisis of the World’s Primates: Why Primates Matter.” Science Advances 3(229): 1–16.

Farmer, Paul. 2006. AIDS and Accusation: Haiti and the Geography of Blame. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Farmer, Paul, Matthew Basilico, Vanessa Kerry, Madeleine Ballard, Anne Becker, Gene Bukhman, Ophelia Dahl, et al. 2013. “Global Health Priorities for the Early Twenty-first Century.” In Reimagining Global Health: An Introduction, edited by Paul Farmer, Jim Yong Kim, Arthur Kleinman, and Matthew Basilico, 302–339. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kenyon, Kathleen. 1979. Archaeology in the Holy Land. New York: W.W. Norton.

Malotki, Ekkehart. 1983. Hopi Time: A Linguistic Analysis of the Temporal Concepts in the Hopi Language. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Mead, Margaret. 1928. Coming of Age in Samoa. Oxford: Morrow.

Ochs, Elinor and Bambi Schieffelin. 2017. “Language Socialization: An Historical Overview.” In Encyclopedia of Language and Education, Volume 8, edited by Patricia Duff, 3-16. New York: Springer.

Rathje, William and Cullen Murphy. 1992. “Five Major Myths about Garbage, and Why They’re Wrong.” Smithsonian 23, no. 4: 113-122.

TANN. 2018. “Mexican Anthropologists Put Face on Nearly 14,000-Year-Old Woman.” Archaeology News Network, August 19, 2018. Accessed on November 16, 2022.

Whorf, Benjamin. 1956. Language, Thought, and Reality. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their many insightful comments and suggestions.

Keith Chan, Ph.D., Grossmont-Cuyamaca Community College District and MiraCosta College

This chapter is a revision from "Chapter 12: Modern Homo sapiens” by Keith Chan. In Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology, first edition, edited by Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera, and Lara Braff, which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Learning Objectives

- Identify the skeletal and behavioral traits that represent modern Homo sapiens.

- Critically evaluate different types of evidence for the origin of our species in Africa and our expansion around the world.

- Understand how the human lifestyle changed when people transitioned from foraging to agriculture.

- Hypothesize how human evolutionary trends may continue into the future.

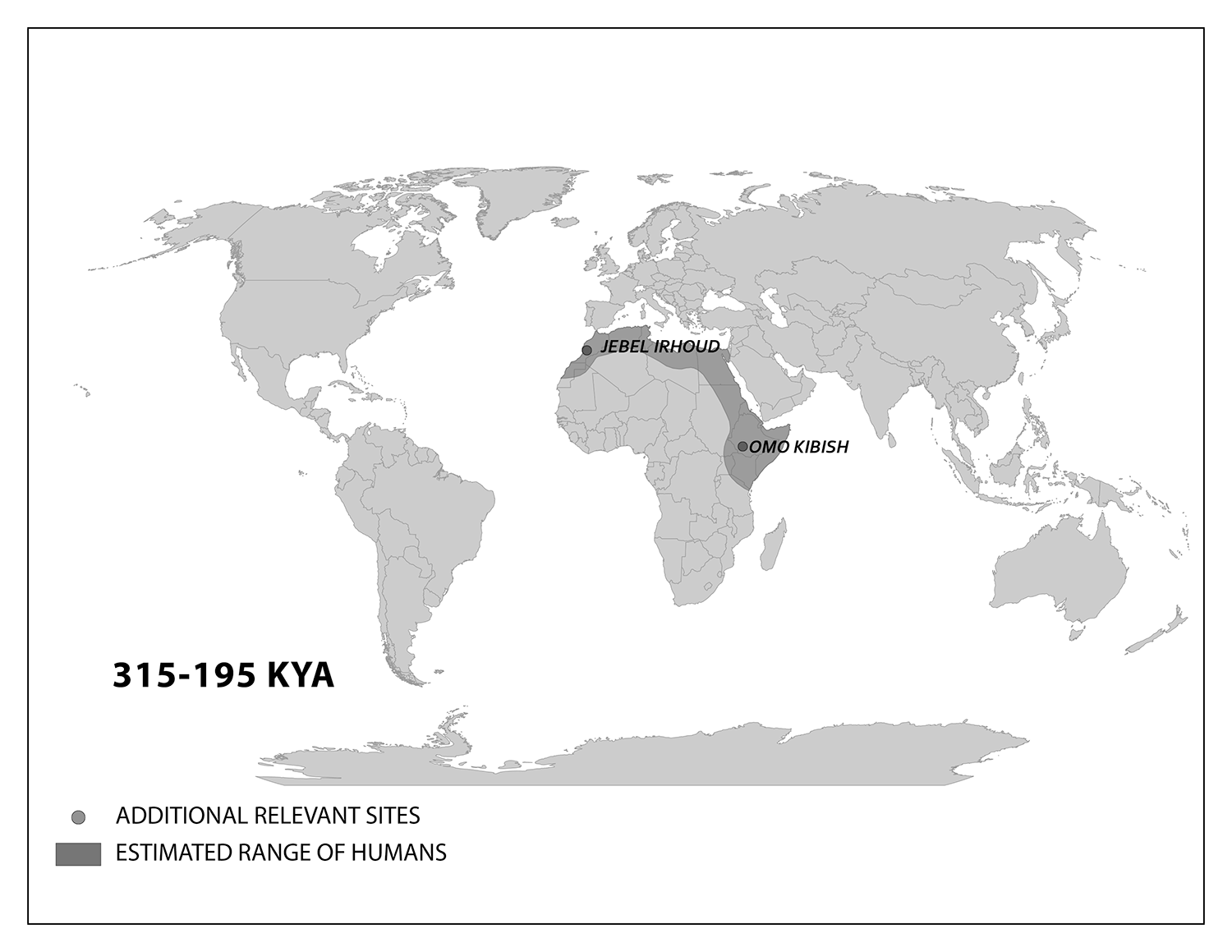

The walls of a pink limestone cave in the hillside of Jebel Irhoud jutted out of the otherwise barren landscape of the Moroccan desert (Figure 13.1). Miners had excavated the cave in the 1960s, revealing some fossils. In 2007, a re-excavation of the site became a momentous occasion for science. A fossil cranium unearthed by a team of researchers was barely visible to the untrained eye. Just the fossil’s robust brows were peering out of the rock. This research team from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology was the latest to explore the ancient human presence in this part of North Africa after a find by miners in 1960. Excavating near the first discovery, the researchers wanted to learn more about how Homo sapiens lived far from East Africa, where we thought our species originated.

The scientists were surprised when they analyzed the cranium, named Irhoud 10, and other fossils. Statistical comparisons with other human crania concluded that the Irhoud face shapes were typical of recent modern humans while the braincases matched ancient modern humans. Based on the findings of other scientists, the team expected these modern Homo sapiens fossils to be around 200,000 years old. Instead, dating revealed that the cranium had been buried for around 315,000 years.

Together, the modern-looking facial dimensions and the older date reshaped the interpretation of our species: modern Homo sapiens. Some key evolutionary changes from the archaic Homo sapiens (described in Chapter 11) to our species today happened 100,000 years earlier than we had thought and across the vast African continent rather than concentrated in its eastern region.

This revelation in the study of modern Homo sapiens is just one of the latest in this continually advancing area of biological anthropology. Researchers today are still discovering amazing fossils and ingenious ways to collect data and test hypotheses about our past. Through the collective work of many scientists, we are building an overall theory of modern human origins.

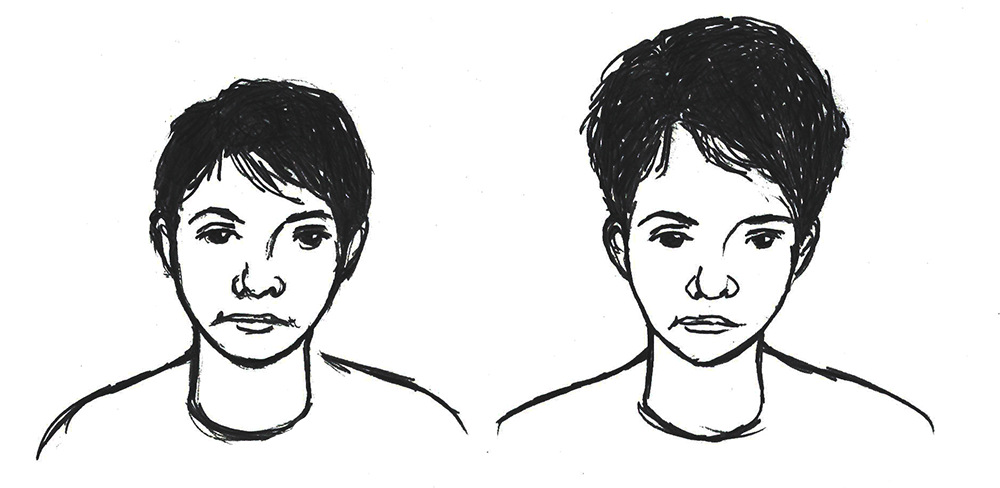

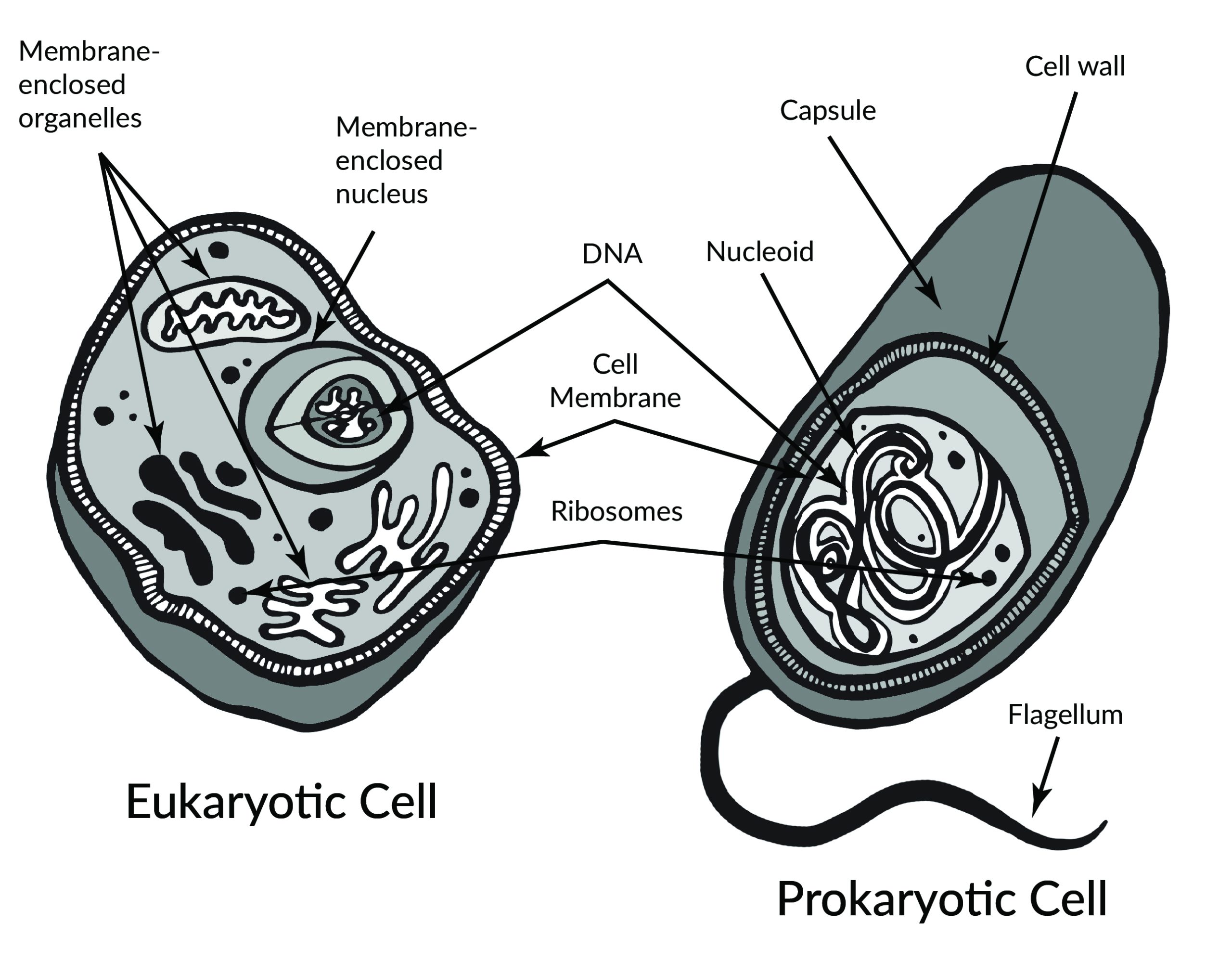

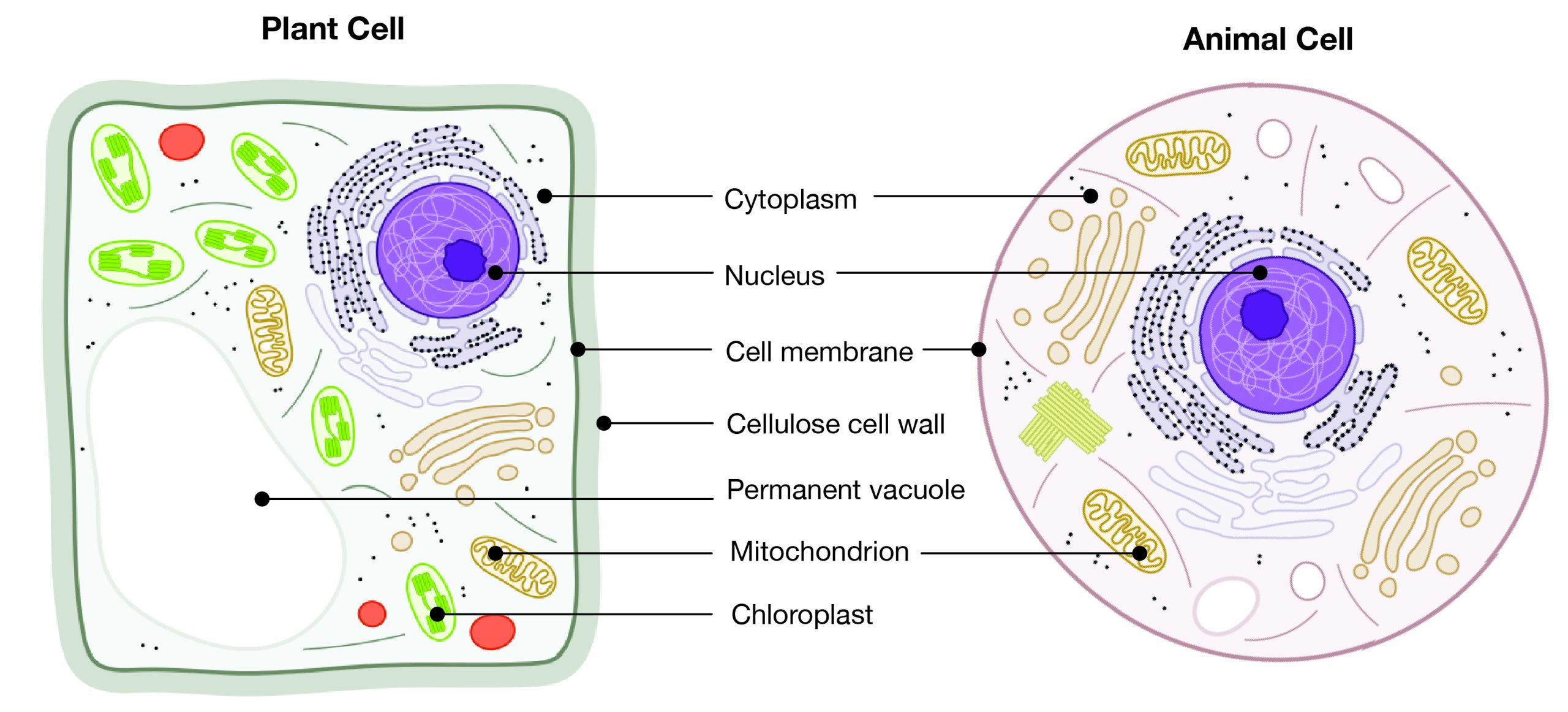

Defining Modernity

What defines modern Homo sapiens when compared to archaic Homo sapiens? Modern humans, like you and me, have a set of derived traits that are not seen in archaic humans or any other hominin. As with other transitions in hominin evolution, such as increasing brain size and bipedal ability, modern traits do not appear fully formed or all at once. In other words, the first modern Homo sapiens was not just born one day from archaic parents. The traits common to modern Homo sapiens appeared in a mosaic manner: gradually and out of sync with one another. There are two areas to consider when tracking the complex evolution of modern human traits. One is the physical change in the skeleton. The other is behavior inferred from the size and shape of the cranium and material culture evidence.

Skeletal Traits

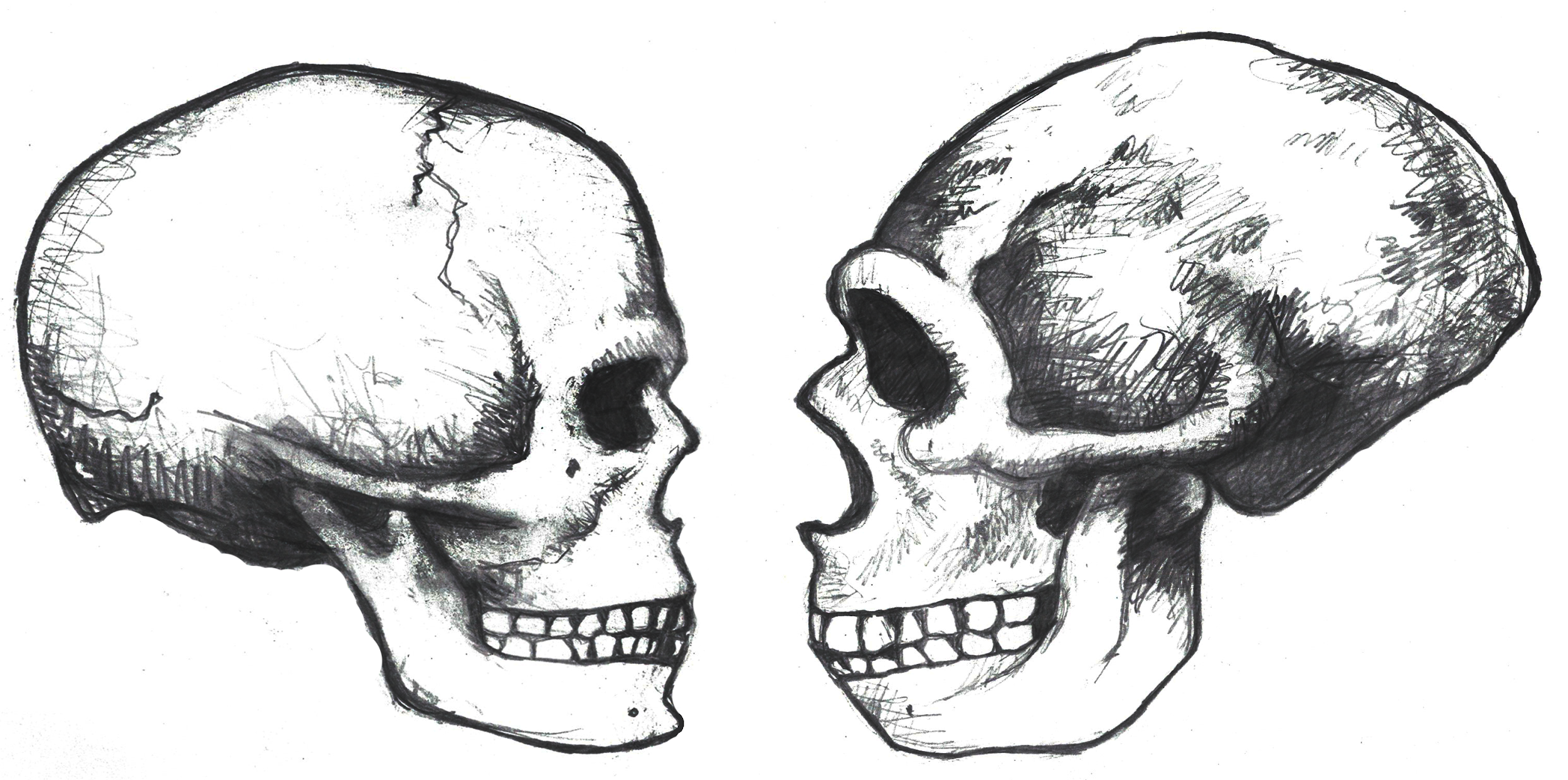

The skeleton of modern Homo sapiens is less robust than that of archaic Homo sapiens. In other words, the modern skeleton is gracile, meaning that the structures are thinner and smoother. Differences related to gracility in the cranium are seen in the braincase, the face, and the mandible. There are also broad differences in the rest of the skeleton.

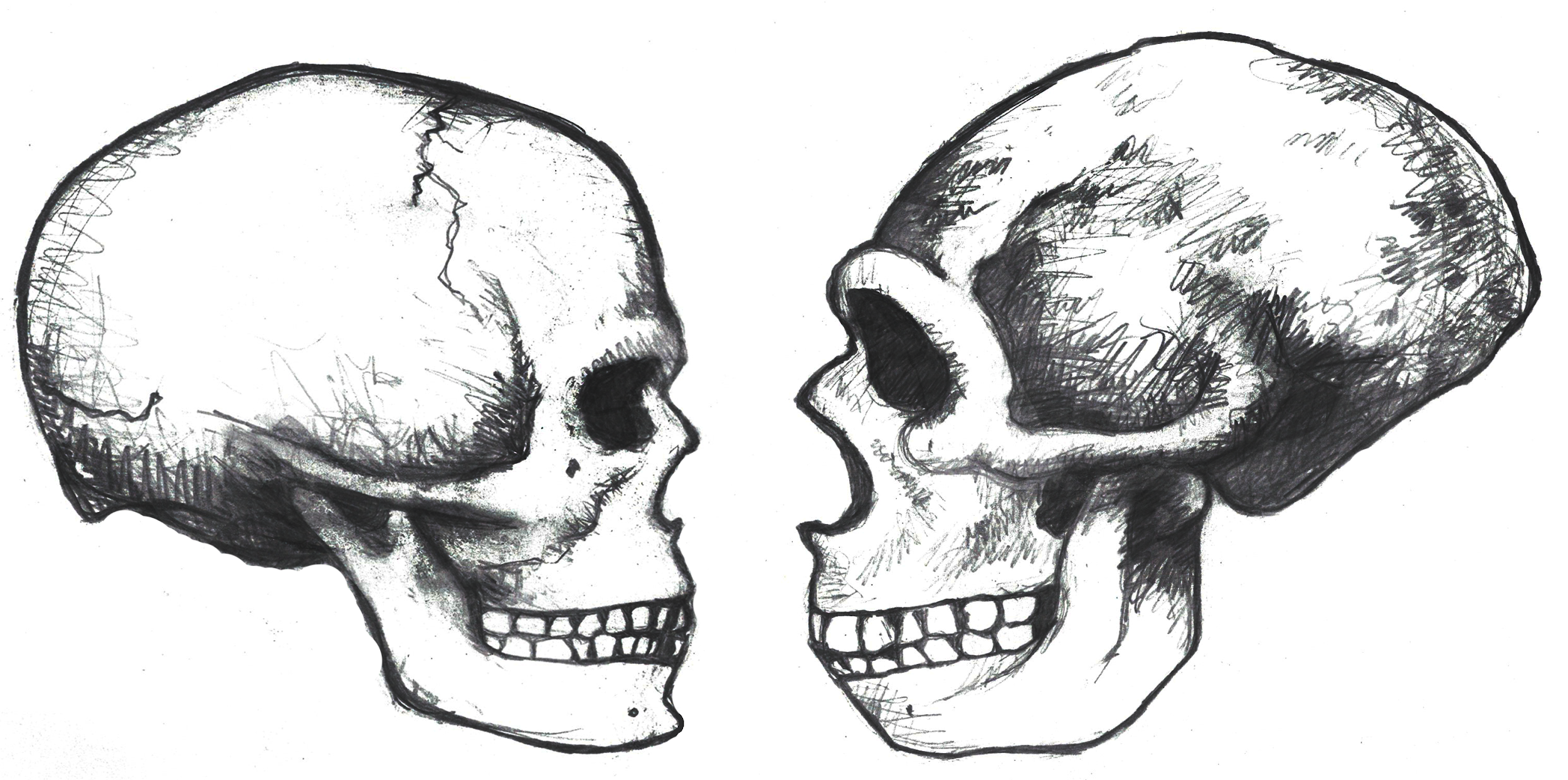

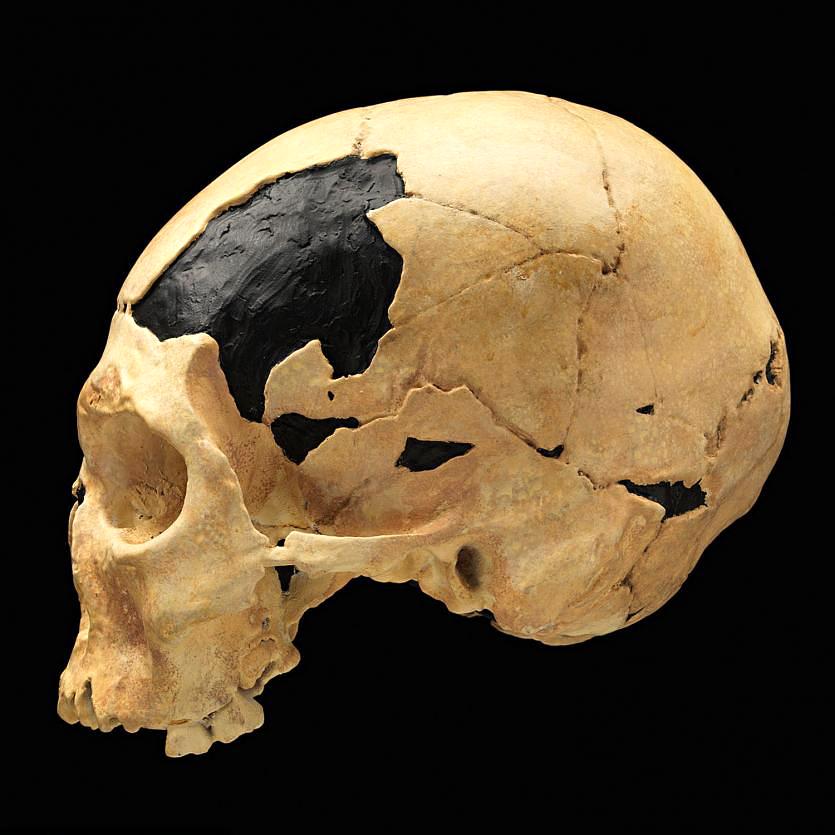

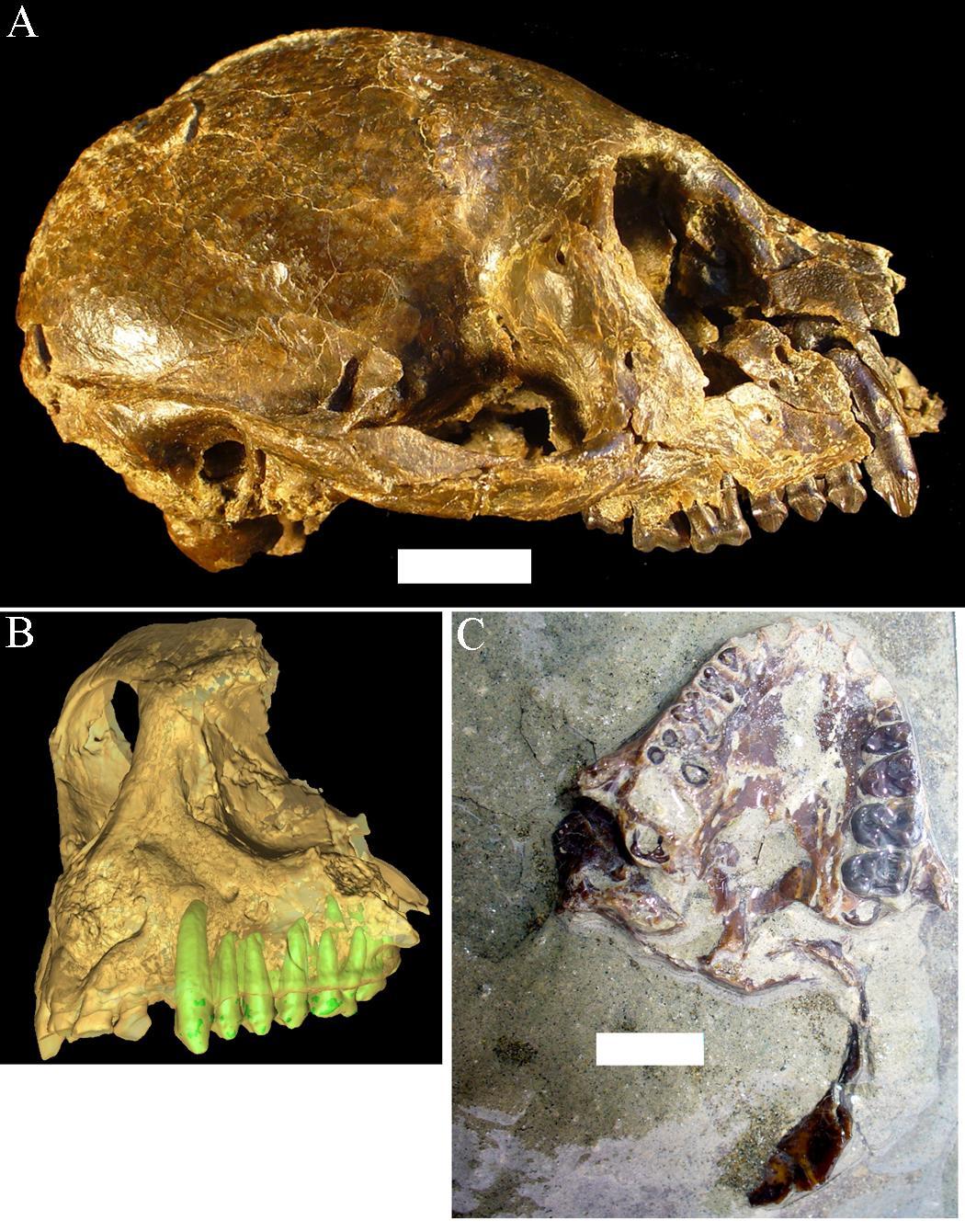

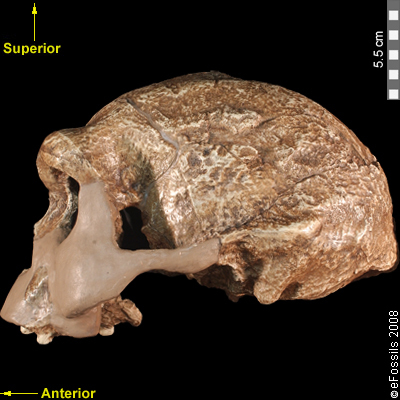

Cranial Traits

Several elements of the braincase differ between modern and archaic Homo sapiens. Overall, the shape is much rounder, or more globular, on a modern skull (Lieberman, McBratney, and Krovitz 2002; Neubauer, Hublin, and Gunz 2018; Pearson 2008; Figure 13.2). You can feel the globularity of your own modern human skull. Feel the height of your forehead with the palm of your hand. Viewed from the side, the tall vertical forehead of a modern Homo sapiens stands out when compared to the sloping archaic version. This is because the frontal lobe of the modern human brain is larger than the one in archaic humans, and the skull has to accommodate the expansion. The vertical forehead reduces a trait that is common to all other hominins: the brow ridge or supraorbital torus. The parietal lobes of the brain and the matching parietal bones on either side of the skull both bulge outward more in modern humans. At the back of the skull, the archaic occipital bun is no longer present. Instead, the occipital region of the modern human cranium has a derived tall and smooth curve, again reflecting the globular brain inside.

The trend of shrinking face size across hominins reaches its extreme with our species as well. The facial bones of a modern Homo sapiens are extremely gracile compared to all other hominins (Lieberman, McBratney, and Krovitz 2002). Continuing a trend in hominin evolution, technological innovations kept reducing the importance of teeth in reproductive success (Lucas 2007). As natural selection favored smaller and smaller teeth, the surrounding bone holding these teeth also shrank.

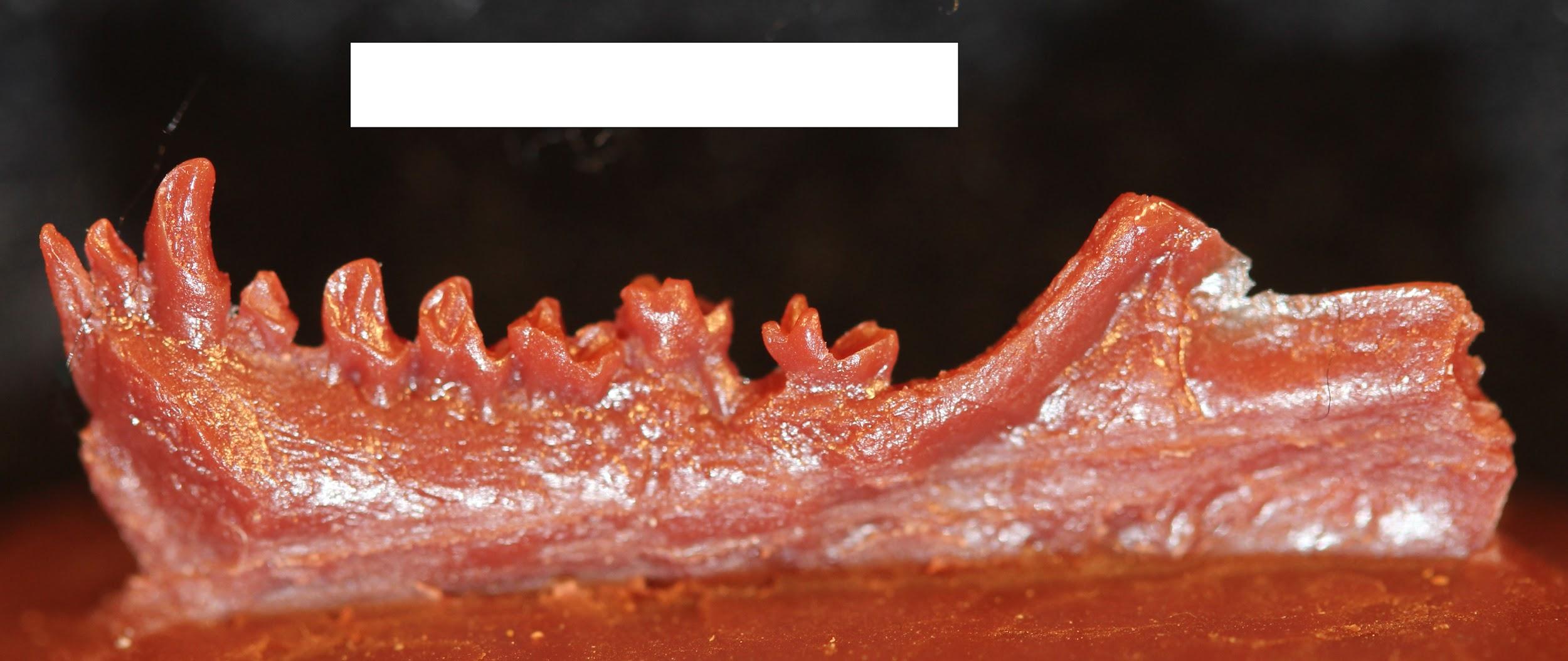

Related to smaller teeth, the mandible is also gracile in modern humans when compared to archaic humans and other hominins. Interestingly, our mandibles have pulled back so far from the prognathism of earlier hominins that we gained an extra structure at the most anterior point, called the mental eminence. You know this structure as the chin. At the skeletal level, it resembles an upside-down “T” at the centerline of the mandible (Pearson 2008). Looking back at archaic humans, you will see that they all lack a chin. Instead, their mandibles curve straight back without a forward point. What is the chin for and how did it develop? Flora Gröning and colleagues (2011) found evidence of the chin’s importance by simulating physical forces on computer models of different mandible shapes. Their results showed that the chin acts as structural support to withstand strain on the otherwise gracile mandible.

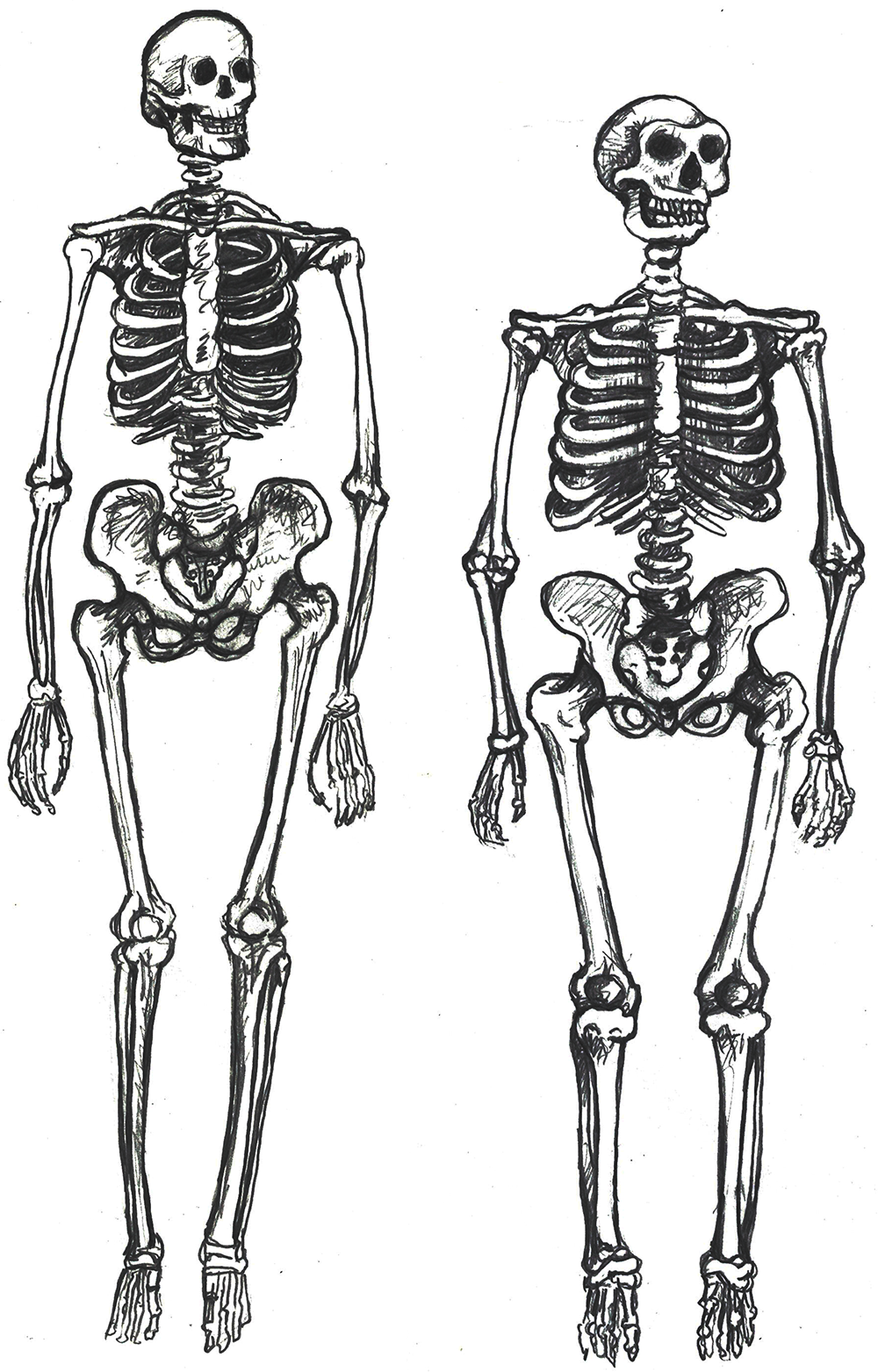

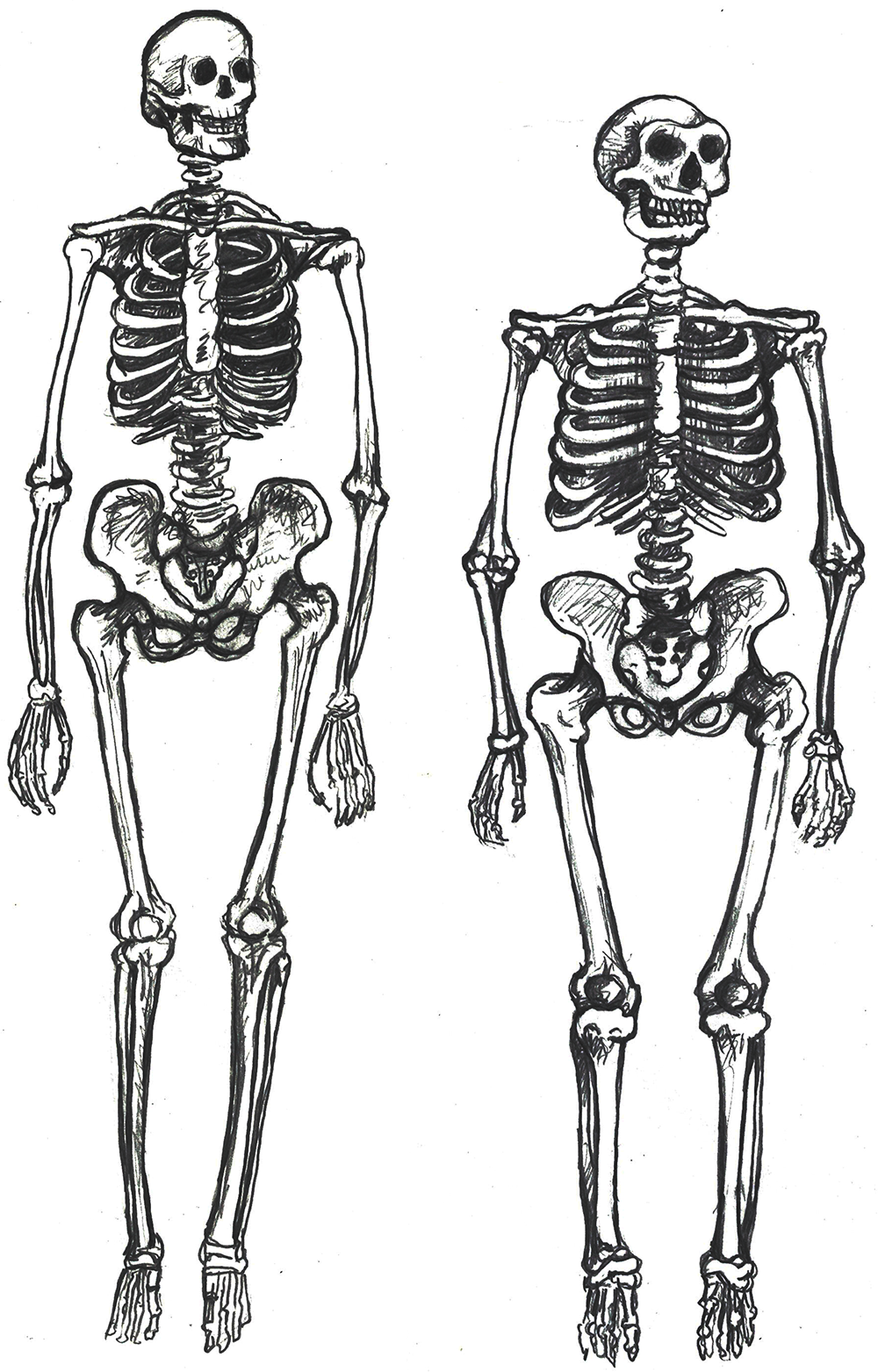

Postcranial Gracility

The rest of the modern human skeleton is also more gracile than its archaic counterpart. The differences are clear when comparing a modern Homo sapiens with a cold-adapted Neanderthal (Sawyer and Maley 2005), but the trends are still present when comparing modern and archaic humans within Africa (Pearson 2000). Overall, a modern Homo sapiens postcranial skeleton has thinner cortical bone, smoother features, and more slender shapes when compared to archaic Homo sapiens (Figure 13.3). Comparing whole skeletons, modern humans have longer limb proportions relative to the length and width of the torso, giving us lankier outlines.

Why is our skeleton so gracile compared to those of other hominins? Natural selection can drive the gracilization of skeletons in several ways (Lieberman 2015). A slender frame is believed to be adapted for the efficient long-distance running ability that started with Homo erectus. Furthermore, it is argued that slenderness is a genetic adaptation for cooling an active body in hotter climates, which aligns with the ample evidence that Africa was the home continent of our species.

Behavioral Modernity

Aside from physical differences in the skeleton, researchers have also uncovered evidence of behavioral changes associated with increased cultural complexity from archaic to modern humans. How did cultural complexity develop? Two investigations into this question are archaeology and the analysis of reconstructed brains.

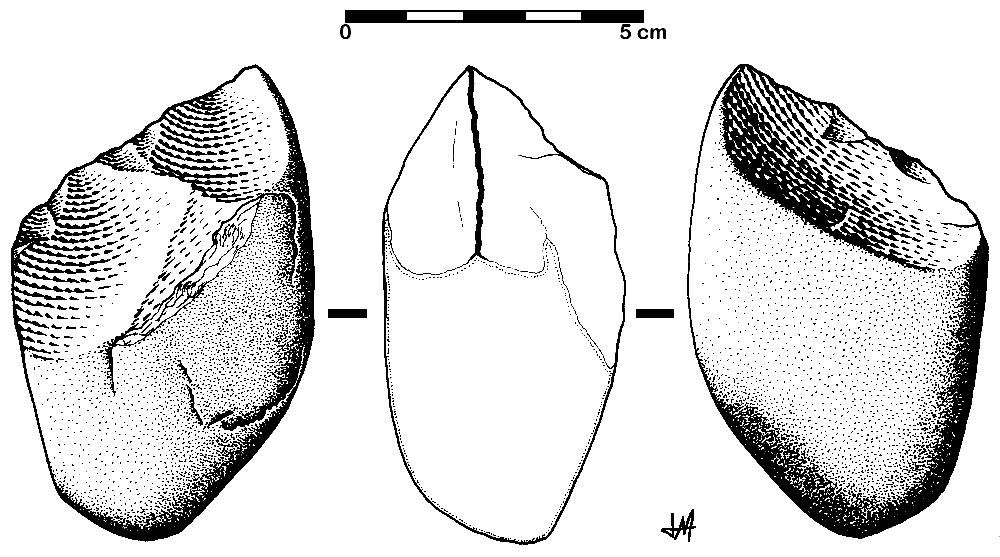

Archaeology tells us much about the behavioral complexity of past humans by interpreting the significance of material culture. In terms of advanced culture, items created with an artistic flair, or as decoration, speak of abstract thought processes (Figure 13.4). The demonstration of difficult artistic techniques and technological complexity hints at social learning and cooperation as well. According to paleoanthropologist John Shea (2011), one way to track the complexity of past behavior through artifacts is by measuring the variety of tools found together. The more types of tools constructed with different techniques and for different purposes, the more modern the behavior. Researchers are still working on an archaeological way to measure cultural complexity that is useful across time and place.

The interpretation of brain anatomy is another promising approach to studying the evolution of human behavior. When looking at investigations on this topic in modern Homo sapiens brains, researchers found a weak association between brain size and test-measured intelligence (Pietschnig et al. 2015). Additionally, they found no association between intelligence and biological sex. These findings mean that there are more significant factors that affect tested intelligence than just brain size. Since the sheer size of the brain is not useful for weighing intelligence within a species, paleoanthropologists are instead investigating the differences in certain brain structures. The differences in organization between modern Homo sapiens brains and archaic Homo sapiens brains may reflect different cognitive priorities that account for modern human culture. As with the archaeological approach, new discoveries will refine what we know about the human brain and apply that knowledge to studying the distant past.

Taken together, the cognitive abilities in modern humans may have translated into an adept use of tools to enhance survival. Researchers Patrick Roberts and Brian A. Stewart (2018) call this concept the generalist-specialist niche: our species is an expert at living in a wide array of environments, with populations culturally specializing in their own particular surroundings. The next section tracks how far around the world these skeletal and behavioral traits have taken us.

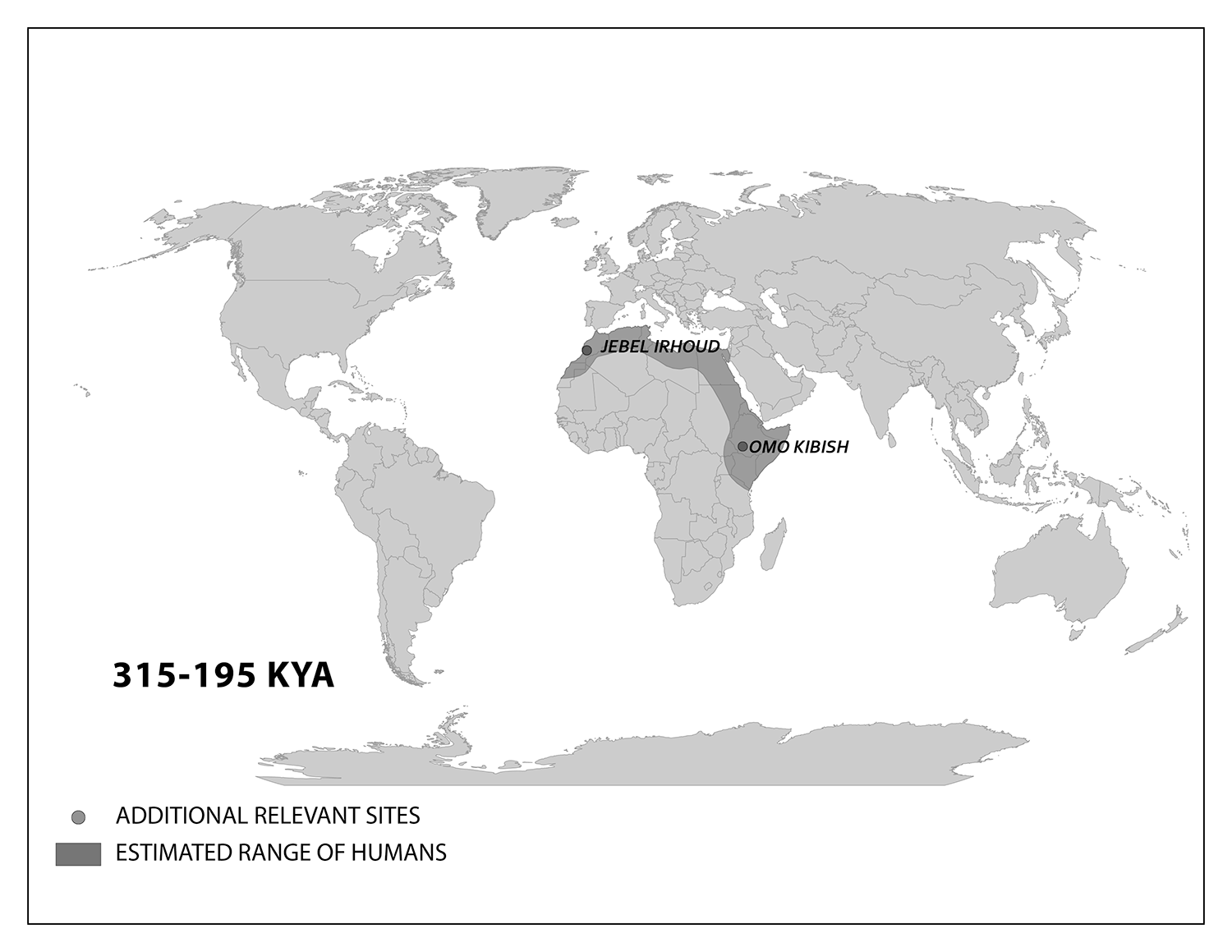

First Africa, Then the World

What enabled modern Homo sapiens to expand its range further in 300,000 years than Homo erectus did in 1.5 million years? The key is the set of derived biological traits from the last section. It is theorized that the gracile frame and neurological anatomy allowed modern humans to survive and even flourish in the vastly different environments they encountered. Based on multiple types of evidence, the source of all of these modern humans was Africa. Instead of originating from just one location, evidence shows that modern Homo sapiens evolution occurred in a complex gene flow network across Africa, a concept called African multiregionalism (Scerri et al. 2018).

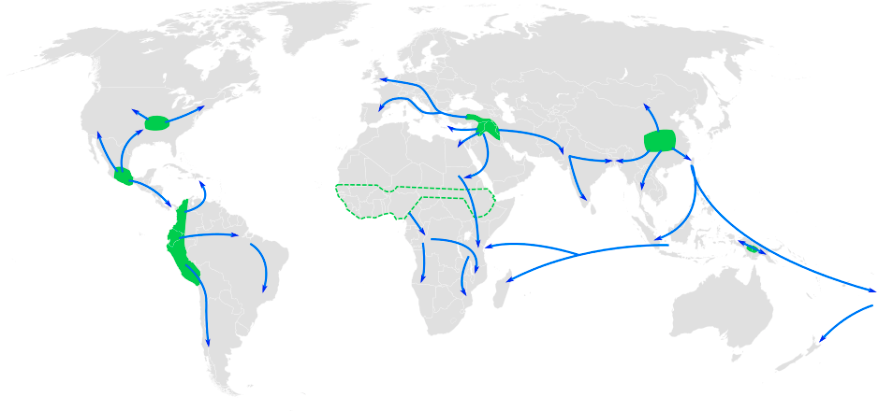

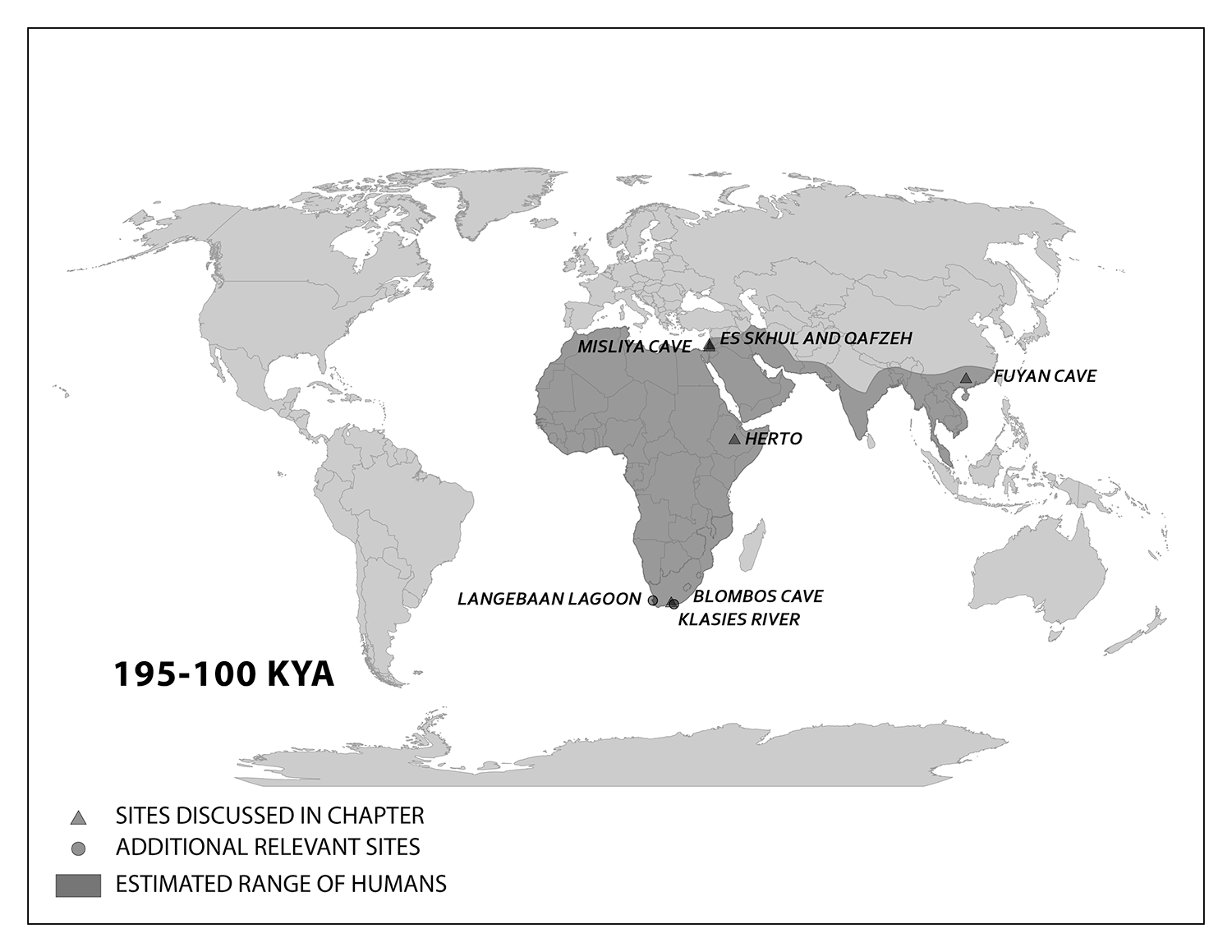

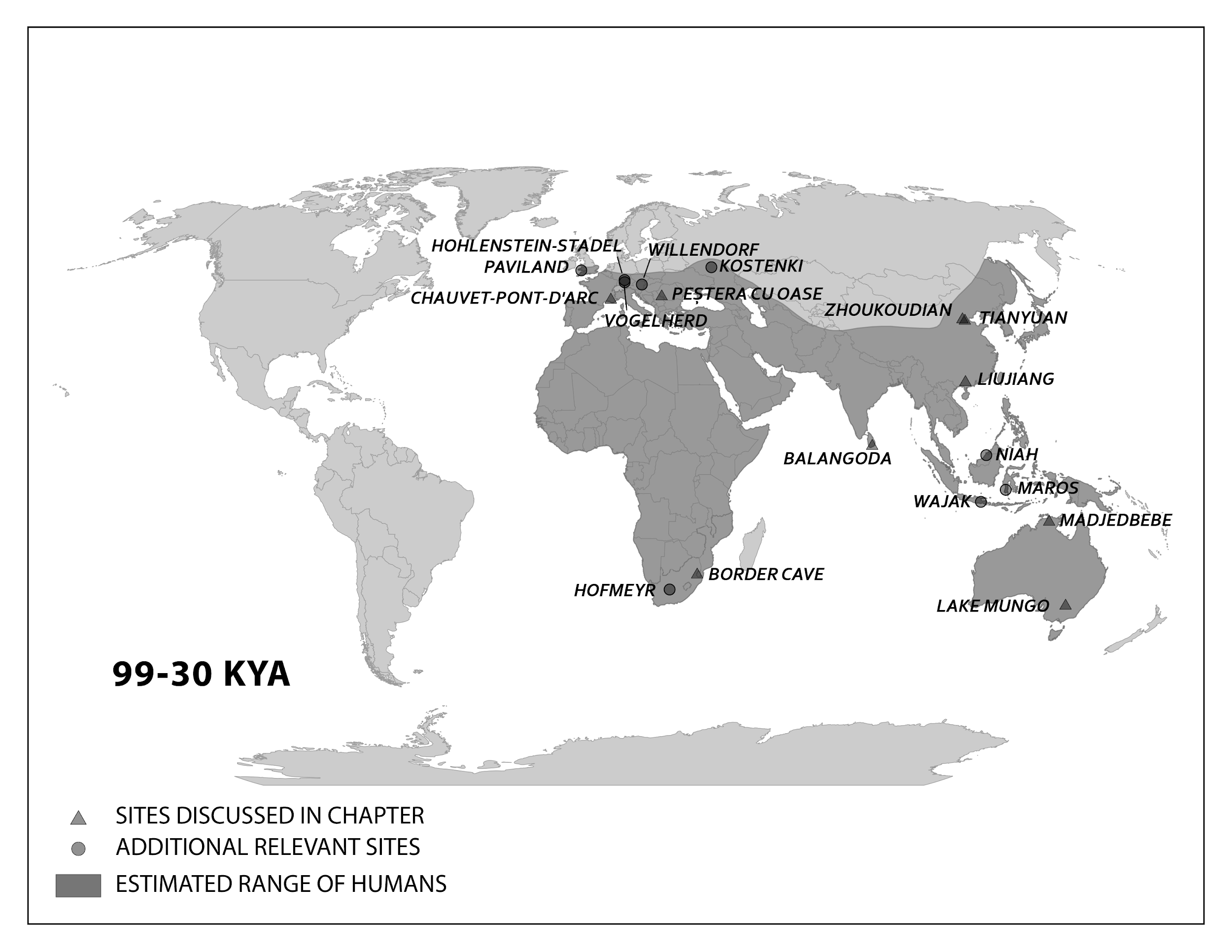

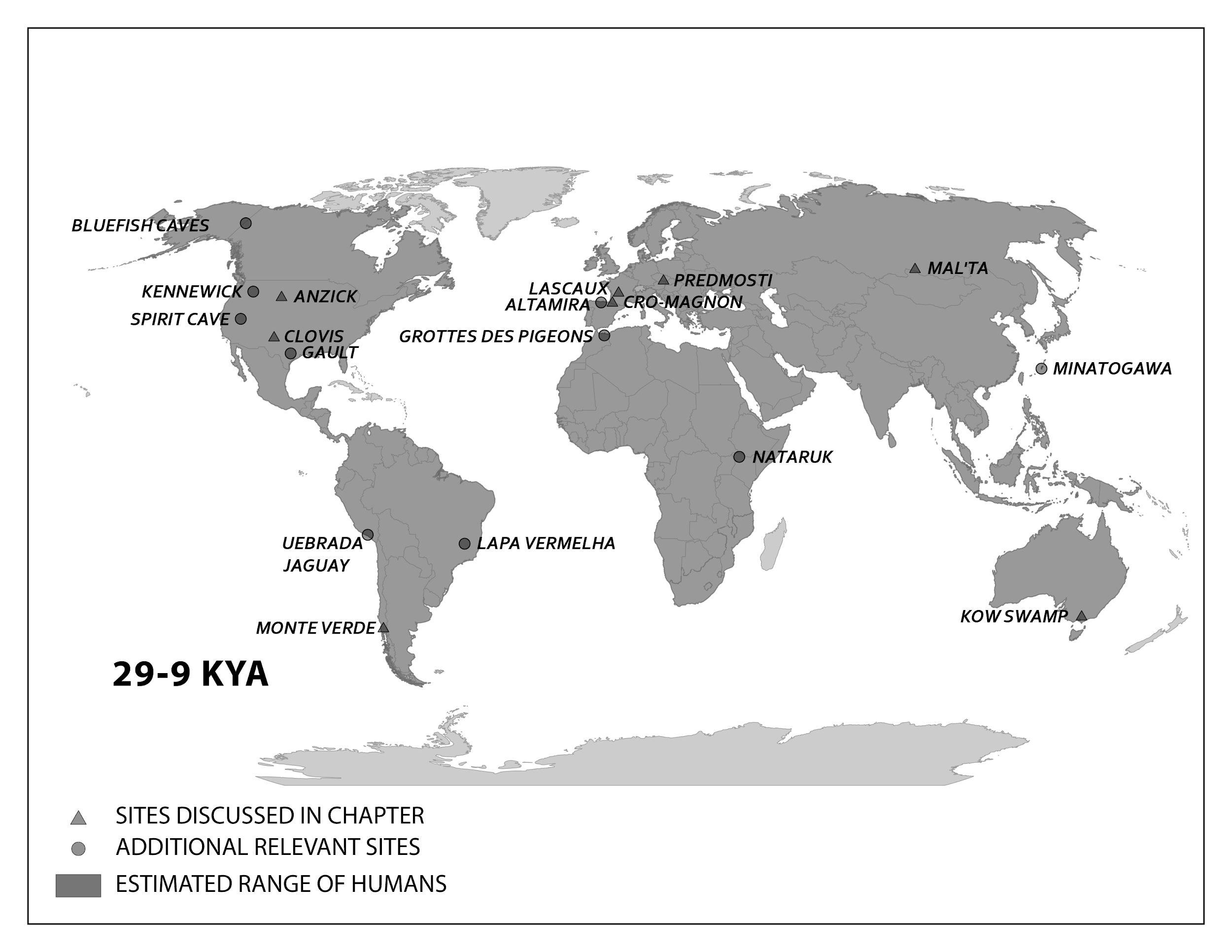

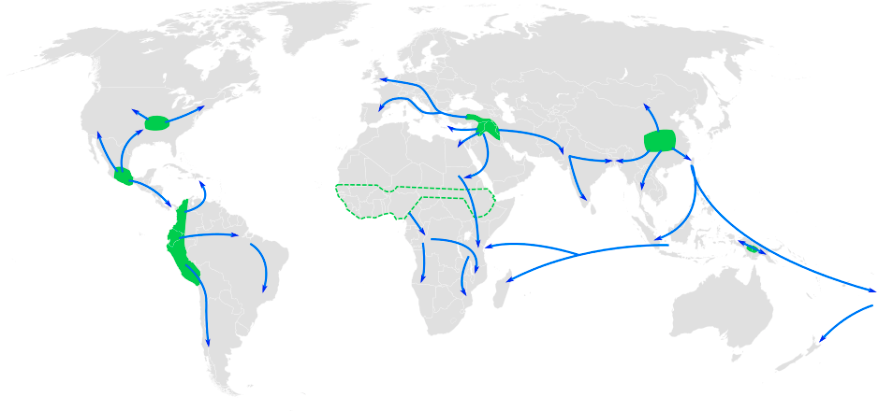

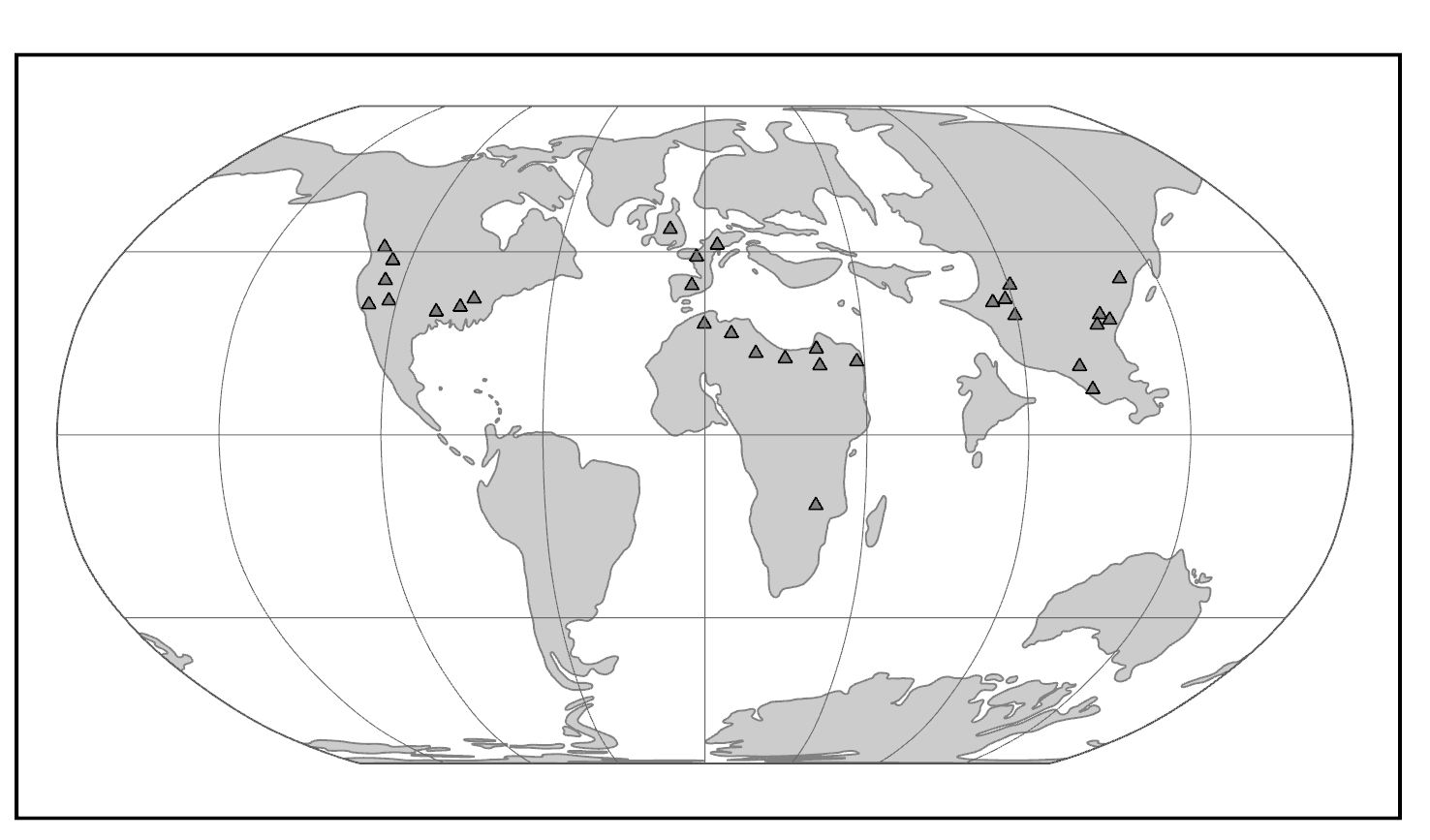

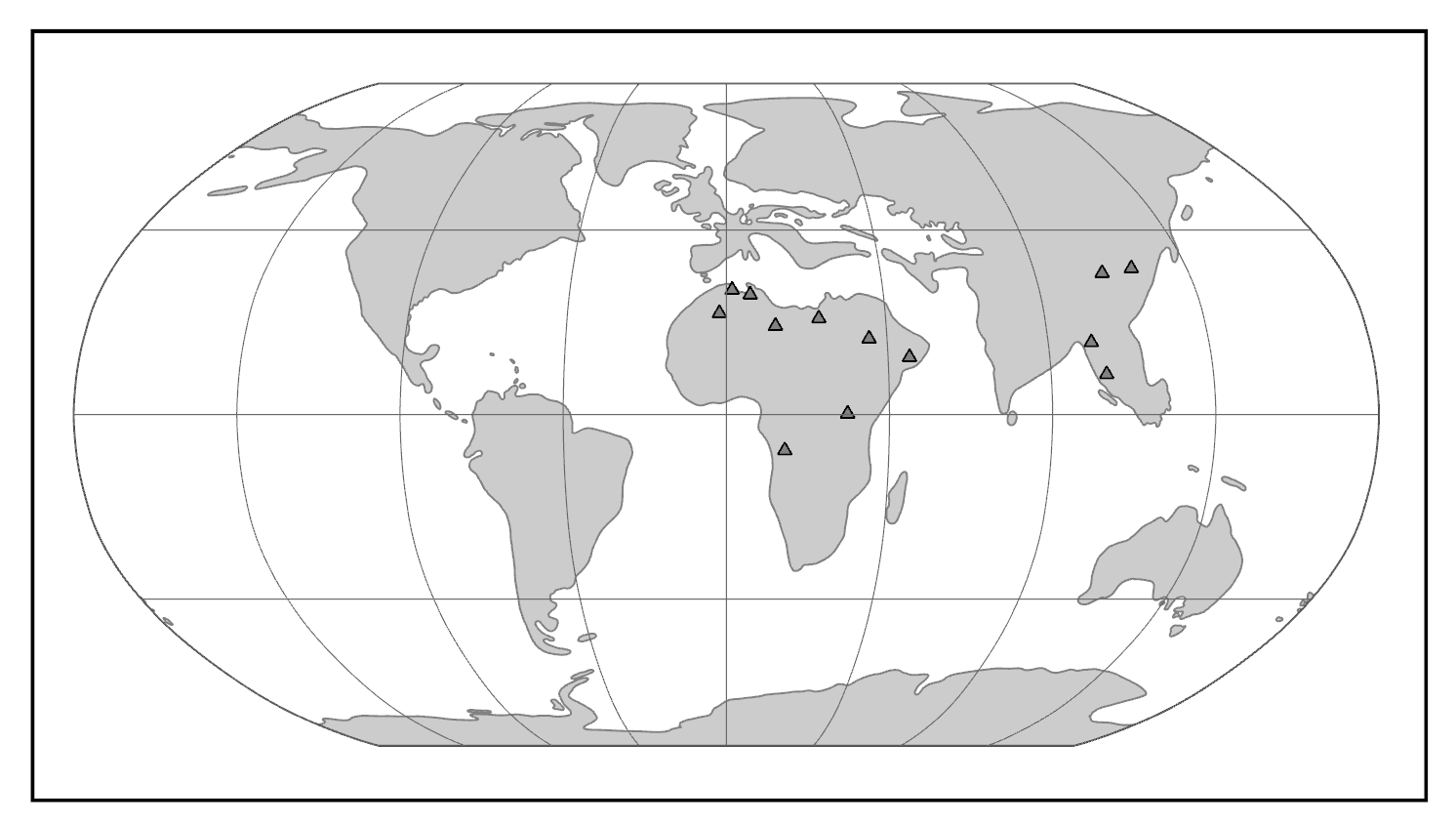

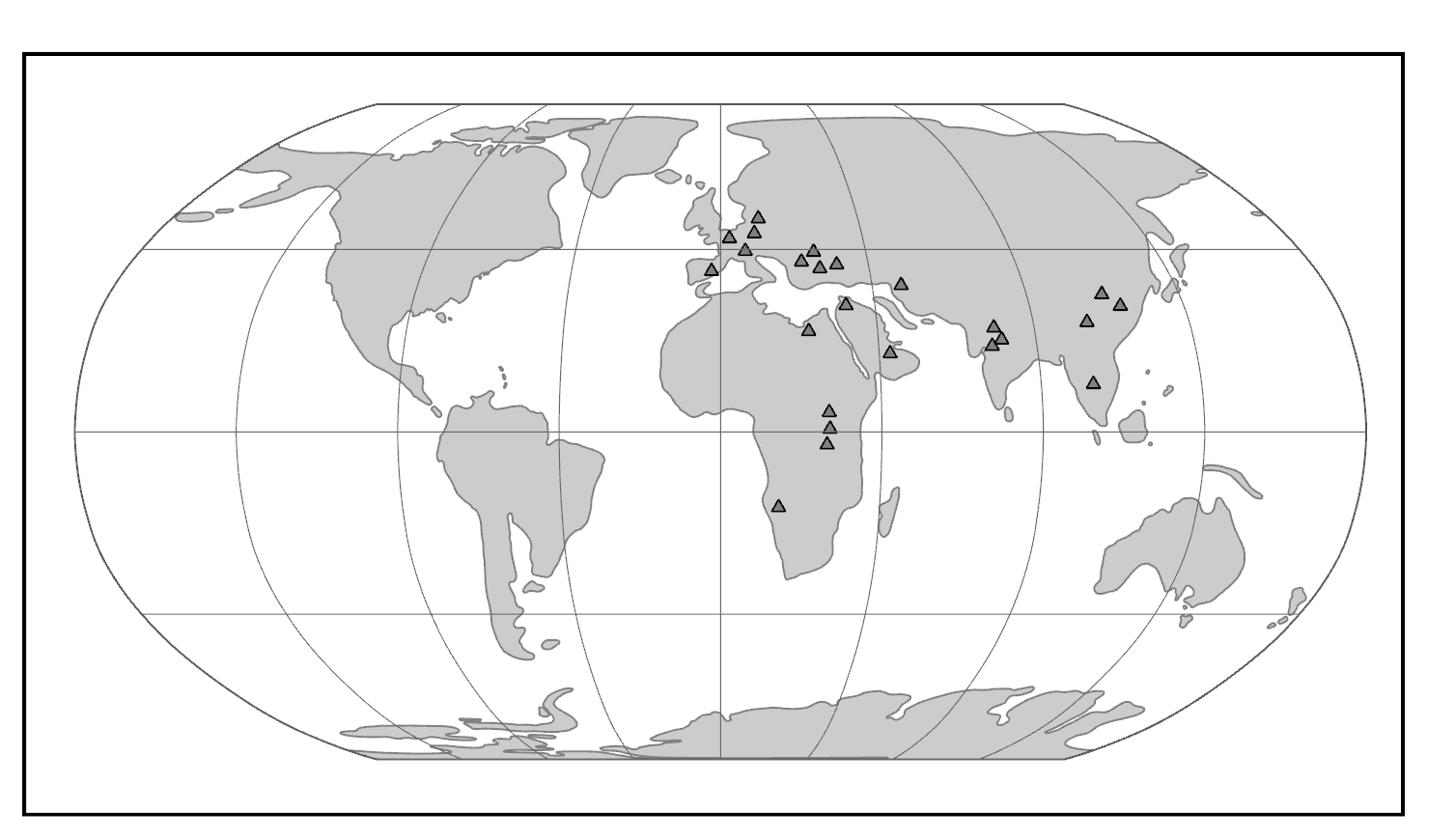

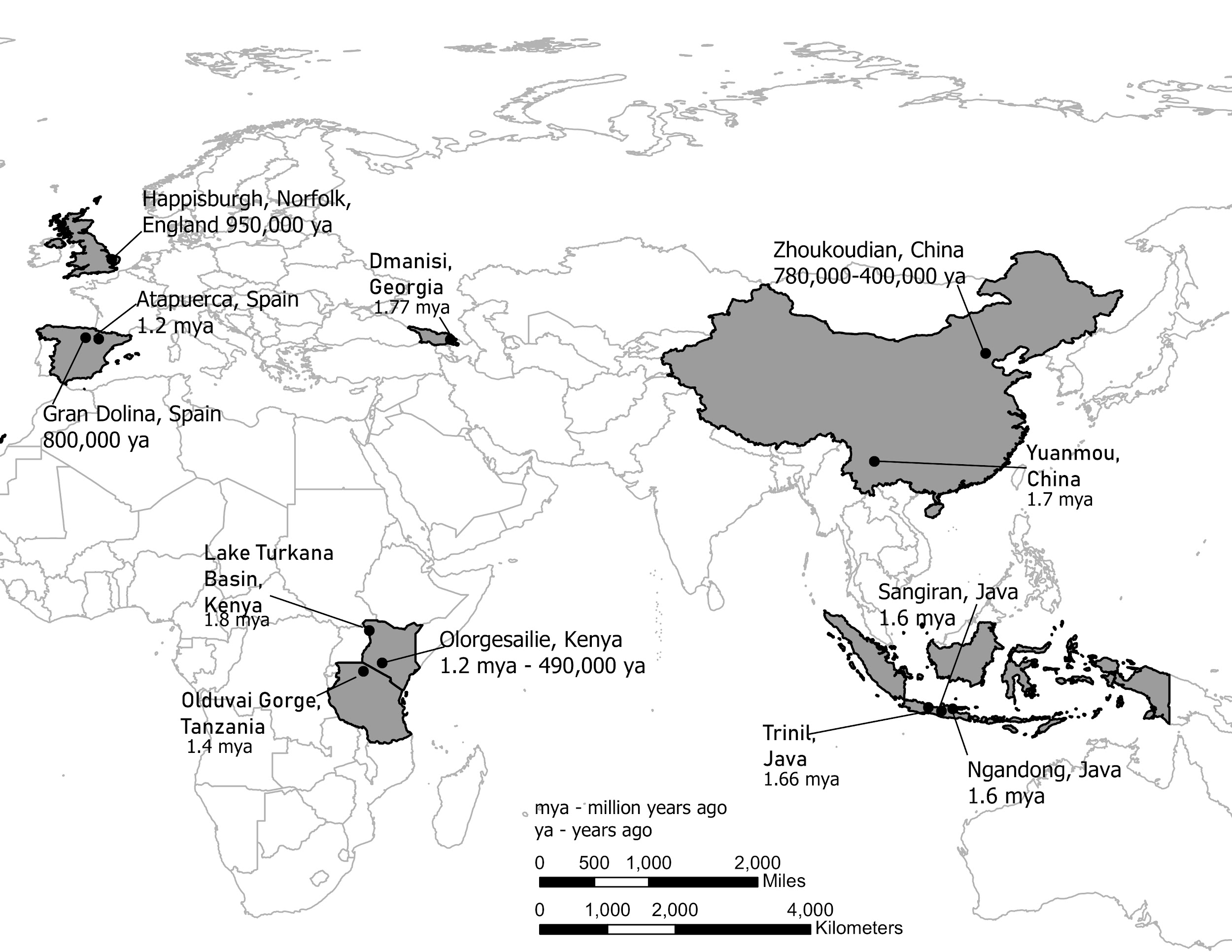

This section traces the origin of modern Homo sapiens and the massive expansion of our species across all of the continents (except Antarctica) by 12,000 years ago. While modern Homo sapiens first shared geography with archaic humans, modern humans eventually spread into lands where no human had gone before. Figure 13.5 shows the broad routes that our species took expanding around the world. I encourage you to make your own timeline with the dates in this part to see the overall trends.

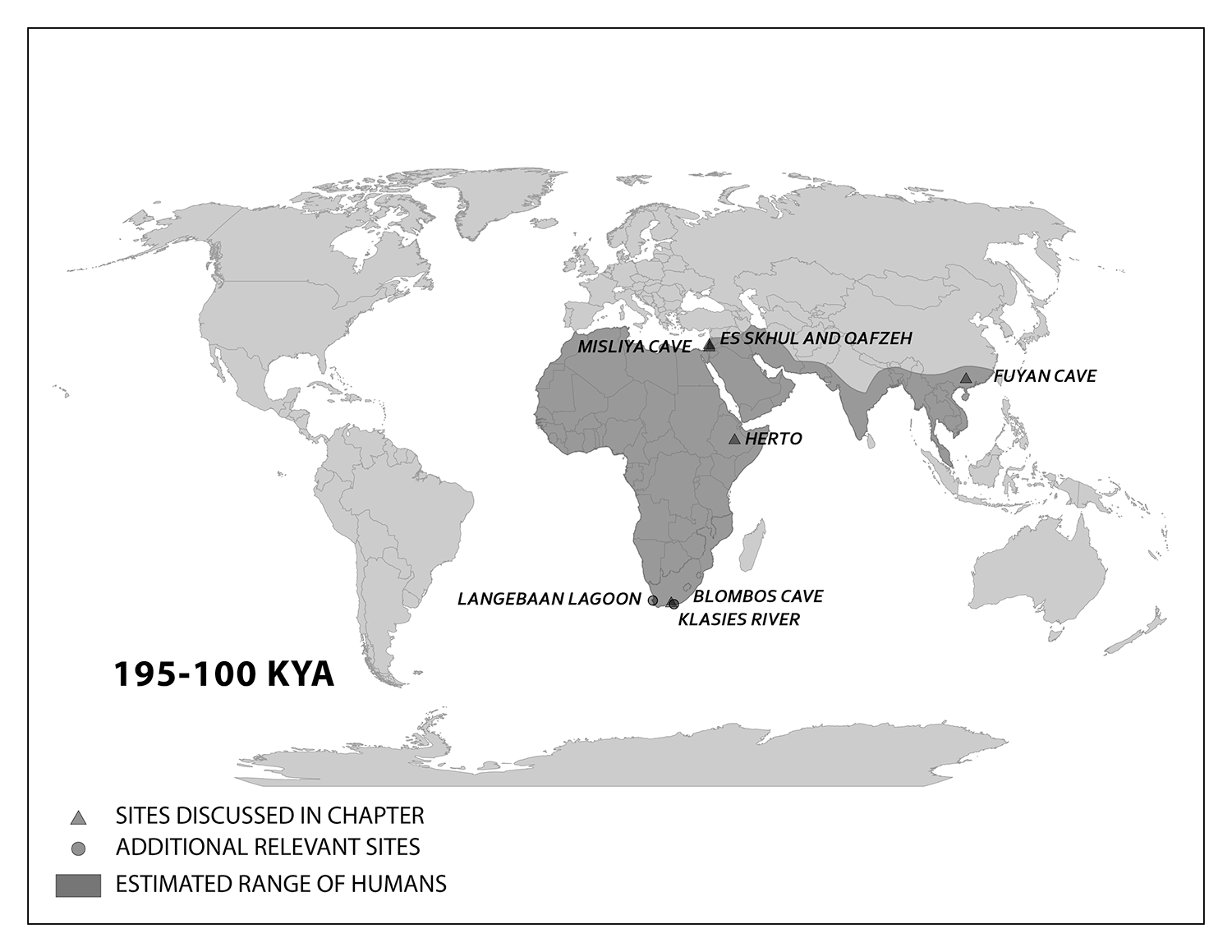

Modern Homo sapiens Biology and Culture in Africa

We start with the ample fossil evidence supporting the theory that modern humans originated in Africa during the Middle Pleistocene, having evolved from African archaic Homo sapiens. The earliest dated fossils considered to be modern actually have a mosaic of archaic and modern traits, showing the complex changes from one type to the other. Experts have various names for these transitional fossils, such as Early Modern Homo sapiens or Early Anatomically Modern Humans. However they are labeled, the presence of some modern traits means that they illustrate the origin of the modern type. Three particularly informative sites with fossils of the earliest modern Homo sapiens are Jebel Irhoud, Omo, and Herto.

Recall from the start of the chapter that the most recent finds at Jebel Irhoud are now the oldest dated fossils that exhibit some facial traits of modern Homo sapiens. Besides Irhoud 10, the cranium that was dated to 315,000 years ago (Hublin et al. 2017; Richter et al. 2017), there were other fossils found in the same deposit that we now know are from the same time period. In total there are at least five individuals, representing life stages from childhood to adulthood. These fossils form an image of high variation in skeletal traits. For example, the skull named Irhoud 1 has a primitive brow ridge, while Irhoud 2 and Irhoud 10 do not (Figure 13.6). The braincases are lower than what is seen in the modern humans of today but higher than in archaic Homo sapiens. The teeth also have a mix of archaic and modern traits that defy clear categorization into either group.

Research separated by nearly four decades uncovered fossils and artifacts from the Kibish Formation in the Lower Omo Valley in Ethiopia. These Omo Kibish hominins were represented by braincases and fragmented postcranial bones of three individuals found kilometers apart, dating back to around 233,000 years ago (Day 1969; McDougall, Brown, and Fleagle 2005; Vidal et al. 2022). One interesting finding was the variation in braincase size between the two more-complete specimens: while the individual named Omo I had a more globular dome, Omo II had an archaic-style long and low cranium.

Also in Ethiopia, a team led by Tim White (2003) excavated numerous fossils at Herto. There were fossilized crania of two adults and a child, along with fragments of more individuals. The dates ranged between 160,000 and 154,000 years ago. The skeletal traits and stone-tool assemblage were both intermediate between the archaic and modern types. Features reminiscent of modern humans included a tall braincase and thinner zygomatic (cheek) bones than those of archaic humans (Figure 13.7). Still, some archaic traits persisted in the Herto fossils, such as the supraorbital tori. Statistical analysis by other research teams concluded that at least some cranial measurements fit just within the modern human range (McCarthy and Lucas 2014), favoring categorization with our own species.

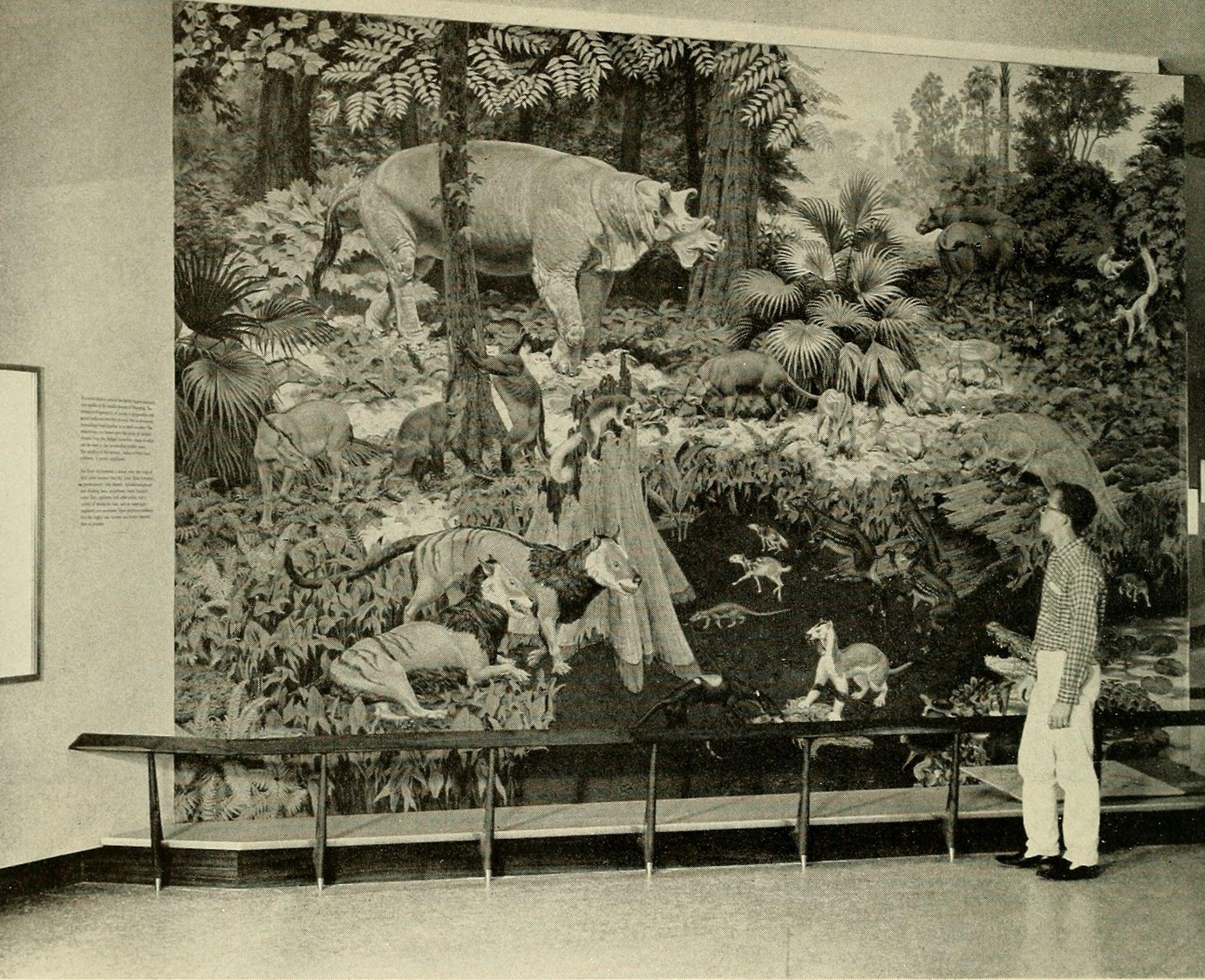

The timeline of material culture suggests a long period of relying on similar tools before a noticeable diversification of artifacts types. Researchers label the time of stable technology shared with archaic types the Middle Stone Age, while the subsequent time of diversification in material culture is called the Later Stone Age.

In the Middle Stone Age, the sites of Jebel Irhoud, Omo, and Herto all bore tools of the same flaked style as archaic assemblages, even though they were separated by almost 150,000 years. The consistency in technology may be evidence that behavioral modernity was not so developed. No clear signs of art dating back this far have been found either. Other hypotheses not related to behavioral modernity could explain these observations. The tool set may have been suitable for thriving in Africa without further innovation. Maybe works of art from that time were made with media that deteriorated or perhaps such art was removed by later humans.

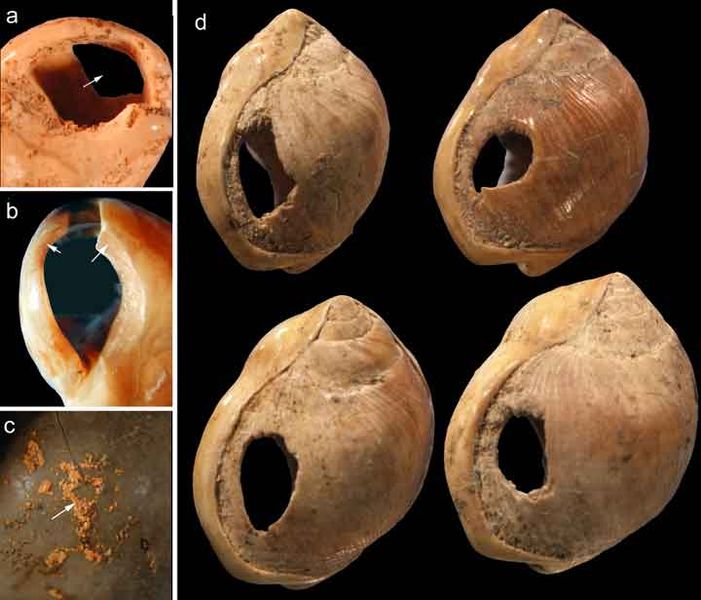

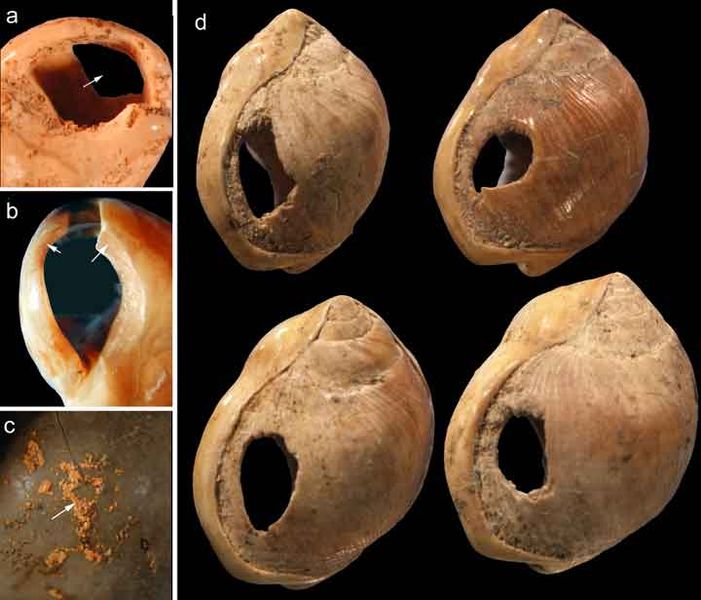

Evidence of what Homo sapiens did in Africa from the end of the Middle Stone Age to the Later Stone Age is concentrated in South African cave sites that reveal the complexity of human behavior at the time. For example, Blombos Cave, located along the present shore of the Cape of Africa facing the Indian Ocean, is notable for having a wide variety of artifacts. The material culture shows that toolmaking and artistry were more complex than previously thought for the Middle Stone Age. In a layer dated to 100,000 years ago, researchers found two intact ochre-processing kits made of abalone shells and grinding stones (Henshilwood et al. 2011). Marine snail shell beads from 75,000 years ago were also excavated (Figure 13.8; d’Errico et al. 2005). Together, the evidence shows that the Middle Stone Age occupation at Blombos Cave incorporated resources from a variety of local environments into their culture, from caves (ochre), open land (animal bones and fat), and the sea (abalone and snail shells). This complexity shows a deep knowledge of the region’s resources and their use—not just for survival but also for symbolic purposes.

On the eastern coast of South Africa, Border Cave shows new African cultural developments at the start of the Later Stone Age. Paola Villa and colleagues (2012) identified several changes in technology around 43,000 years ago. Stone-tool production transitioned from a slower process to one that was faster and made many microliths, small and precise stone tools. Changes in decorations were also found across the Later Stone Age transition. Beads were made from a new resource: fragments of ostrich eggs shaped into circular forms resembling present-day breakfast cereal O’s (d’Errico et al. 2012). These beads show a higher level of altering one’s own surroundings and a move from the natural to the abstract in terms of design.

Expansion into the Middle East and Asia

While modern Homo sapiens lived across Africa, some members eventually left the continent. These pioneers could have used two connections to the Middle East or West Asia. From North Africa, they could have crossed the Sinai Peninsula and moved north to the Levant, or eastern Mediterranean. Finds in that region show an early modern human presence. Other finds support the Southern Dispersal model, with a crossing from East Africa to the southern Arabian Peninsula through the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb. It is tempting to think of one momentous event in which people stepped off Africa and into the Middle East, never to look back. In reality, there were likely multiple waves of movement producing gene flow back and forth across these regions as the overall range pushed east. The expanding modern human population could have thrived by using resources along the southern coast of the Arabian Peninsula to South Asia, with side routes moving north along rivers. The maximum range of the species then grew across Asia.

Modern Homo sapiens in the Middle East

Geographically, the Middle East is the ideal place for the African modern Homo sapiens population to inhabit upon expanding out of their home continent. In the Eastern Mediterranean coast of the Levant, there is a wealth of skeletal and material culture linked to modern Homo sapiens. Recent discoveries from Saudi Arabia further add to our view of human life just beyond Africa.

The Caves of Mount Carmel in present-day Israel have preserved skeletal remains and artifacts of modern Homo sapiens, the first-known group living outside Africa. The skeletal presence at Misliya Cave is represented by just part of the left upper jaw of one individual, but it is notable for being dated to a very early time, between 194,000 and 177,000 years ago (Hershkovitz et al. 2018). Later, from 120,000 to 90,000 years ago, fossils of multiple individuals across life stages were found in the caves of Es-Skhul and Qafzeh (Shea and Bar-Yosef 2005). The skeletons had many modern Homo sapiens traits, such as globular crania and more gracile postcranial bones when compared to Neanderthals. Still, there were some archaic traits. For example, the adult male Skhul V also possessed what researchers Daniel Lieberman, Osbjorn Pearson, and Kenneth Mowbray (2000) called marked or clear occipital bunning. Also, compared to later modern humans, the Mount Carmel people were more robust. Skhul V had a particularly impressive brow ridge that was short in height but sharply jutted forward above the eyes (Figure 13.9). The high level of preservation is due to the intentional burial of some of these people. Besides skeletal material, there are signs of artistic or symbolic behavior. For example, the adult male Skhul V had a boar’s jaw on his chest. Similarly, Qafzeh 11, a juvenile with healed cranial trauma, had an impressive deer antler rack placed over his torso (Figure 13.10; Coqueugniot et al. 2014). Perforated seashells colored with ochre, mineral-based pigment, were also found in Qafzeh (Bar-Yosef Mayer, Vandermeersch, and Bar-Yosef 2009).

One remaining question is, what happened to the modern humans of the Levant after 90,000 years ago? Another site attributed to our species did not appear in the region until 47,000 years ago. Competition with Neanderthals may have accounted for the disappearance of modern human occupation since the Neanderthal presence in the Levant lasted longer than the dates of the early modern Homo sapiens. John Shea and Ofer Bar-Yosef (2005) hypothesized that the Mount Carmel modern humans were an initial expansion from Africa that failed. Perhaps they could not succeed due to competition with the Neanderthals who had been there longer and had both cultural and biological adaptations to that environment.

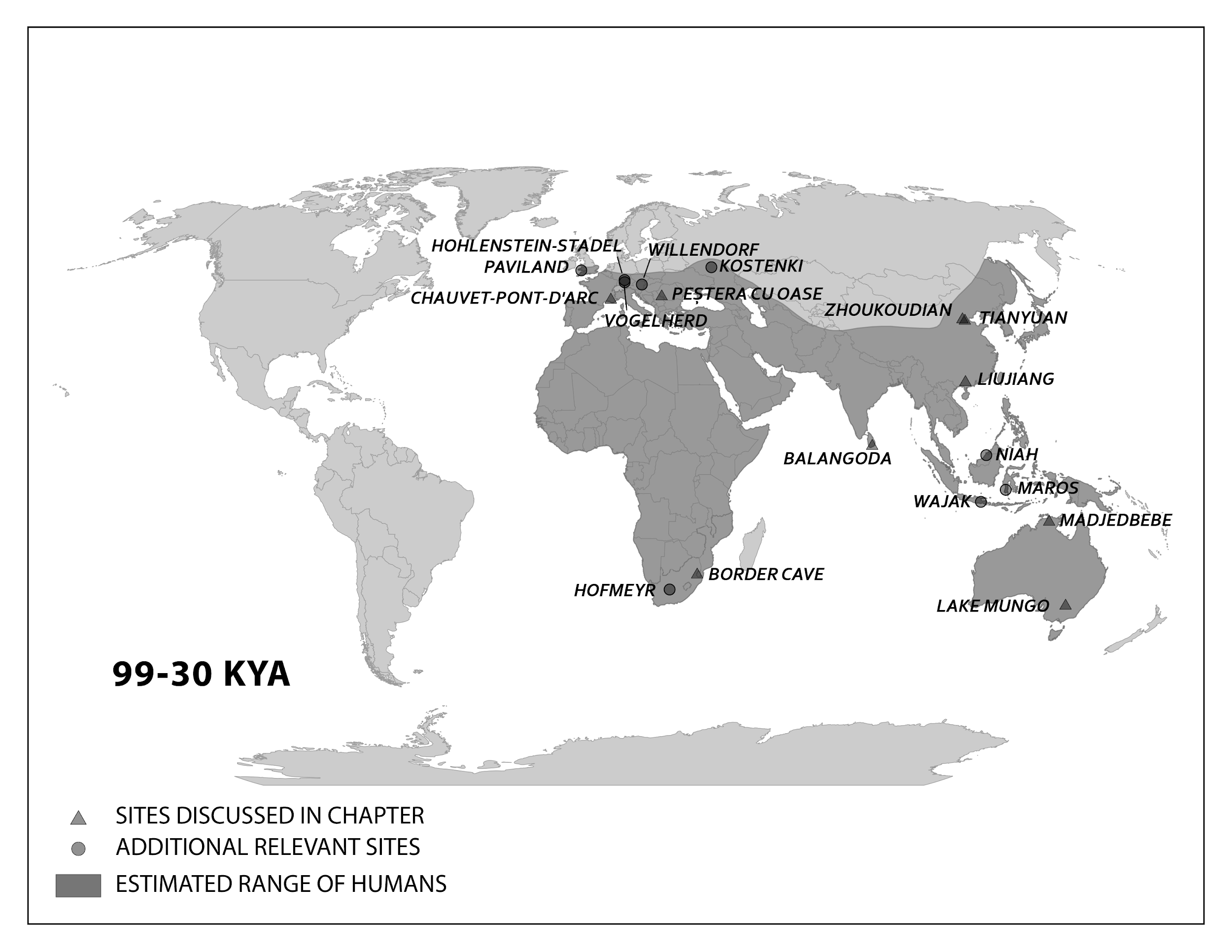

Modern Homo sapiens of China

A long history of paleoanthropology in China has found ample evidence of modern human presence. Four notable sites are the caves at Fuyan, Liujiang, Tianyuan, and Zhoukoudian. In the distant past, these caves would have been at least seasonal shelters that unintentionally preserved evidence of human presence for modern researchers to discover.

At Fuyan Cave in Southern China, paleoanthropologists found 47 adult teeth associated with cave formations dated to between 120,000 and 80,000 years ago (Liu et al. 2015). It is currently the oldest-known modern human site in China, though other researchers question the validity of the date range (Michel et al. 2016). The teeth have the small size and gracile features of modern Homo sapiens dentition.

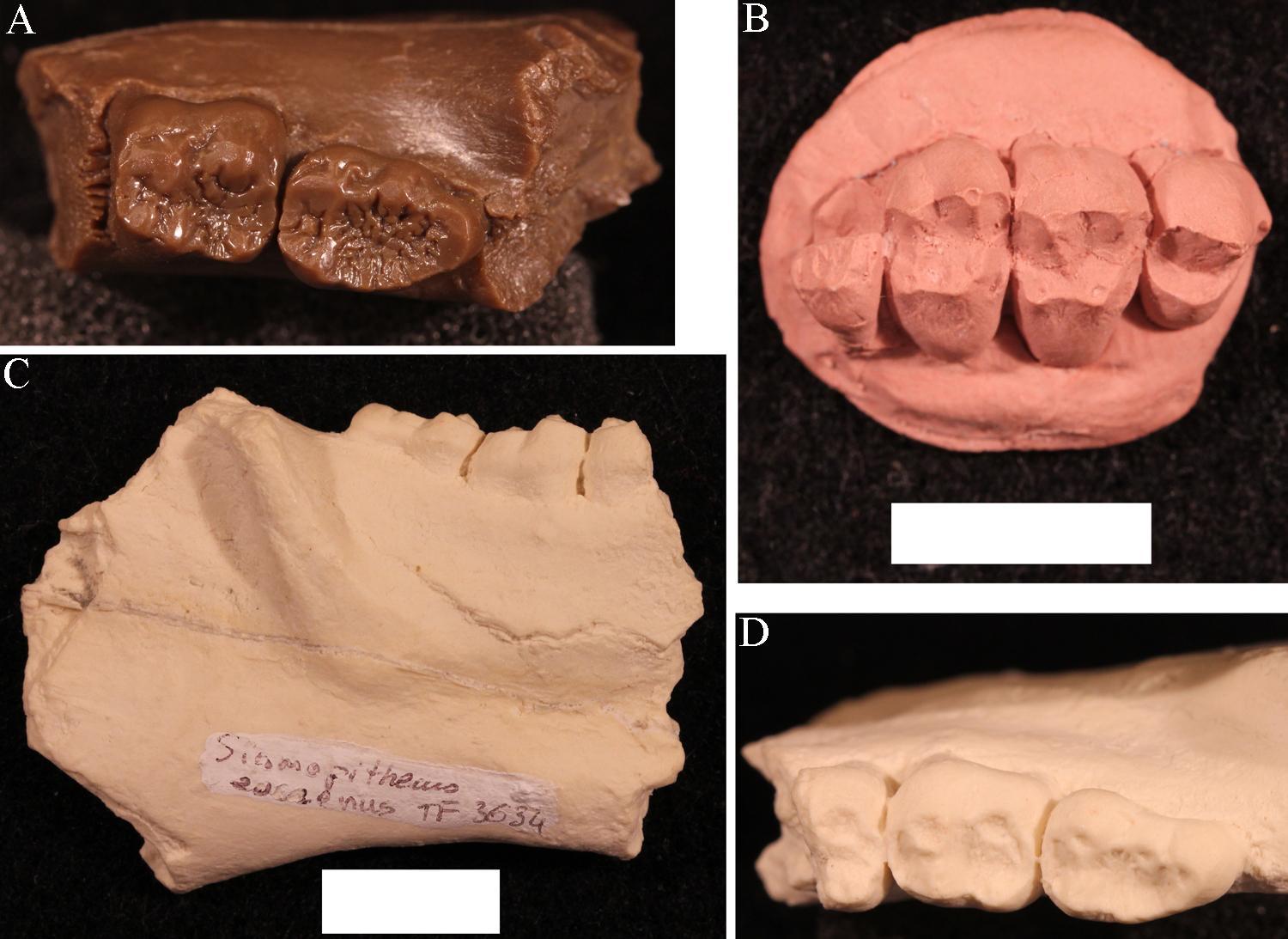

The fossil Liujiang (or Liukiang) hominin (67,000 years ago) has derived traits that classified it as a modern Homo sapiens, though primitive archaic traits were also present. In the skull, which was found nearly complete, the Liujiang hominin had a taller forehead than archaic Homo sapiens but also had an enlarged occipital region (Figure 13.11; Brown 1999; Wu et al. 2008). Other parts of the skeleton also had a mix of modern and archaic traits: for example, the femur fragments suggested a slender length but with thick bone walls (Woo 1959).

Another Chinese site to describe here is the one that has been studied the longest. In the Zhoukoudian Cave system (Figure 13.12), where Homo erectus and archaic Homo sapiens have also been found, there were three crania of modern Homo sapiens. These crania, which date to between 34,000 and 10,000 years ago, were all more globular than those of archaic humans but still lower and longer than those of later modern humans (Brown 1999; Harvati 2009). When compared to one another, the crania showed significant differences from one another. Comparison of cranial measurements to other populations past and present found no connection with modern East Asians, again showing that human variation was very different from what we see today.

Crossing to Australia

Expansion of the first modern human Asians, still following the coast, eventually entered an area that researchers call Sunda before continuing on to modern Australia. Sunda was a landmass made up of the modern-day Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Java, and Borneo. Lowered sea levels connected these places with land bridges, making them easier to traverse. Proceeding past Sunda meant navigating Wallacea, the archipelago that includes the Indonesian islands east of Borneo. In the distant past, there were many megafauna, large animals that migrating humans would have used for food and materials (such as utilizing animals’ hides and bones). Further southeast was another landmass called Sahul, which included New Guinea and Australia as one contiguous continent. Based on fossil evidence, this land had never seen hominins or any other primates before modern Homo sapiens arrived. Sites along this path offer clues about how our species handled the new environment to live successfully as foragers.

The skeletal remains at Lake Mungo, land traditionally owned by Mutthi Mutthi, Ngiampaa, and Paakantji peoples, are the oldest known in the continent. The now-dry lake was one of a series located along the southern coast of Australia in New South Wales, far from where the first people entered from the north (Barbetti and Allen 1972; Bowler et al. 1970). Two individuals dating to around 40,000 years ago show signs of artistic and symbolic behavior, including intentional burial. The bones of Lake Mungo 1 (LM1), an adult female, were crushed repeatedly, colored with red ochre, and cremated (Bowler et al. 1970). Lake Mungo 3 (LM3), a tall, older male with a gracile cranium but robust postcranial bones, had his fingers interlocked over his pelvic region (Brown 2000).

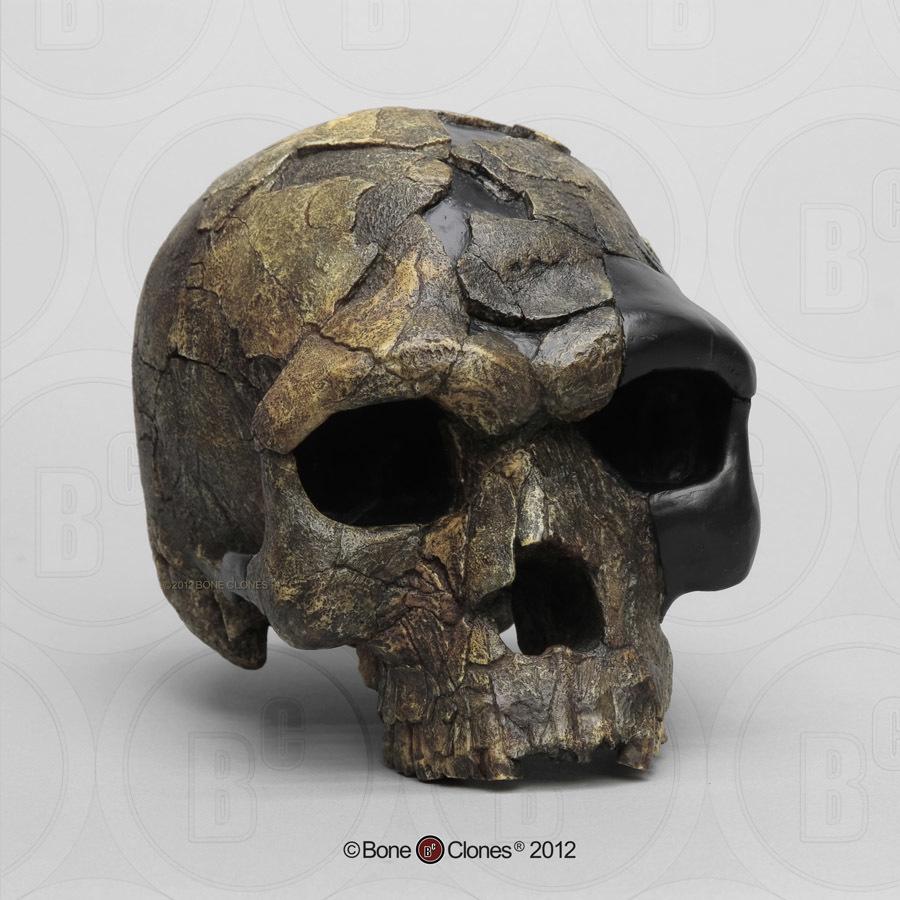

Kow Swamp, within traditional Yorta Yorta land also in southern Australia, contained human crania that looked distinctly different from the ones at Lake Mungo (Durband 2014; Thorne and Macumber 1972). The crania, dated between 9,000 and 20,000 years ago, had extremely robust brow ridges and thick bone walls, but these were paired with globular features on the braincase (Figure 13.13).

While no fossil humans have been found at the Madjedbebe rock shelter in the North Territory of Australia, more than 10,000 artifacts found there show both behavioral modernity and variability (Clarkson et al. 2017). They include a diverse array of stone tools and different shades of ochre for rock art, including mica-based reflective pigment (similar to glitter). These impressive artifacts are as far back as 56,000 years old, providing the date for the earliest-known presence of humans in Australia.

From the Levant to Europe

The first modern human expansion into Europe occurred after other members of our species settled in East Asia and Australia. As the evidence from the Levant suggests, modern human movement to Europe may have been hampered by the presence of Neanderthals. It is suggested that another obstacle was the colder climate, which was incompatible with the biology of modern Homo sapiens from Africa, as they were adapted to high temperatures and ultraviolet radiation. Still, by 40,000 years ago, modern Homo sapiens had a detectable presence. This time was also the start of the Later Stone Age or Upper Paleolithic, when there was an expansion in cultural complexity. There is a wealth of evidence from this region due to a Western bias in research, the proximity of these findings to Western scientific institutions, and the desire of Western scientists to explore their own past.

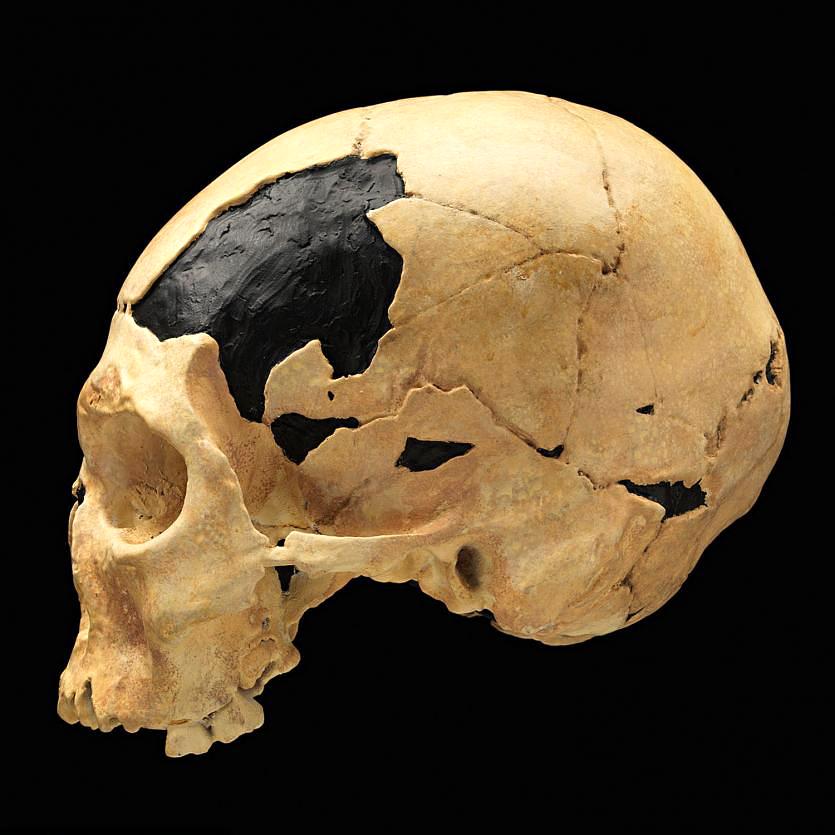

In Romania, the site of Peștera cu Oase (Cave of Bones) had the oldest-known remains of modern Homo sapiens in Europe, dated to around 40,000 years ago (Trinkaus et al. 2003a). Among the bones and teeth of many animals were the fragmented cranium of one person and the mandible of another (the two bones did not fit each other). Both bones have modern human traits similar to the fossils from the Middle East, but they also had Neanderthal traits. Oase 1, the mandible, had a mental eminence but also extremely large molars (Trinkaus et al. 2003b). This mandible has yielded DNA that surprisingly is equally similar to DNA from present-day Europeans and Asians (Fu et al. 2015). This means that Oase 1 was not the direct ancestor of modern Europeans. The Oase 2 cranium has the derived traits of reduced brow ridges along with archaic wide zygomatic cheekbones and an occipital bun (Figure 13.14; Rougier et al. 2007).

Dating to around 26,000 years ago, Předmostí near Přerov in the Czech Republic was a site where people buried over 30 individuals along with many artifacts. Eighteen individuals were found in one mass burial area, a few covered by the scapulae of woolly mammoths (Germonpré, Lázničková-Galetová, and Sablin 2012). The Předmostí crania were more globular than those of archaic humans but tended to be longer and lower than in later modern humans (Figure 13.15; Velemínská et al. 2008). The height of the face was in line with modern residents of Central Europe. There was also skeletal evidence of dog domestication, such as the presence of dog skulls with shorter snouts than in wild wolves (Germonpré, Lázničková-Galetová, and Sablin et al. 2012). In total, Předmostí could have been a settlement dependent on mammoths for subsistence and the artificial selection of early domesticated dogs.

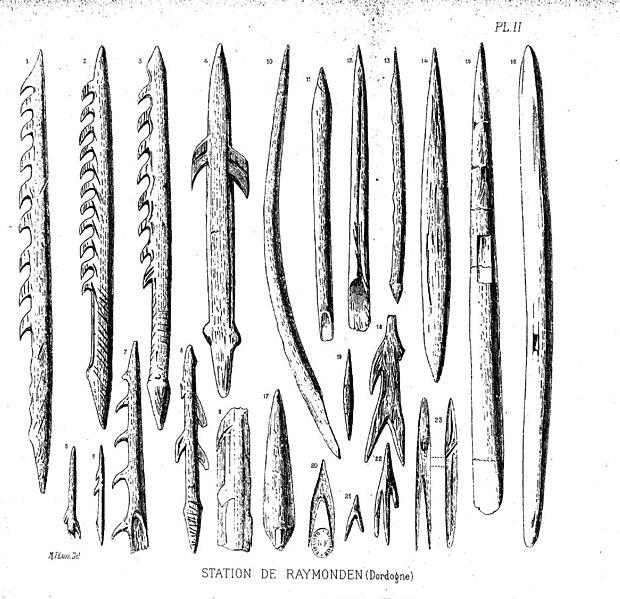

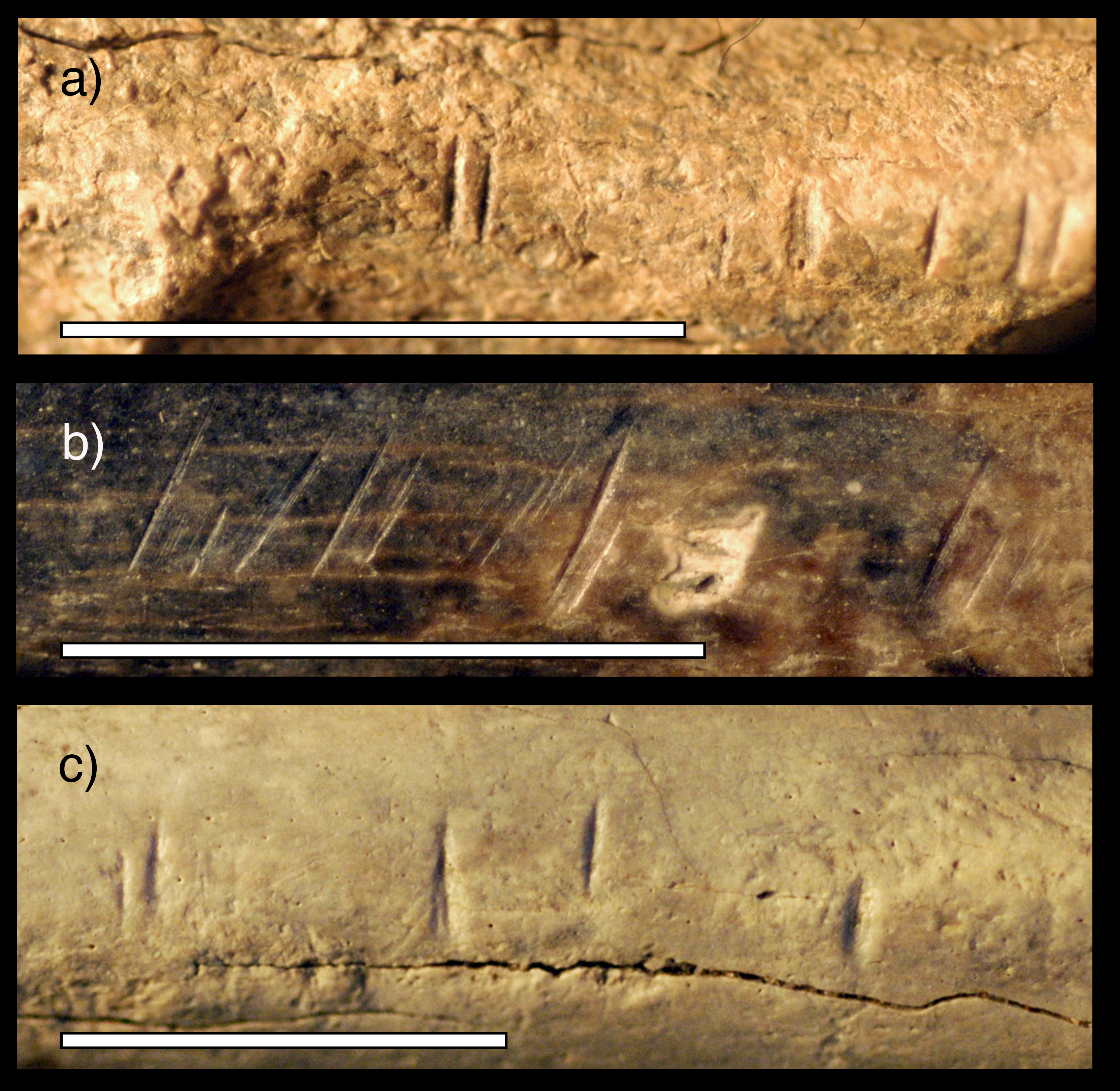

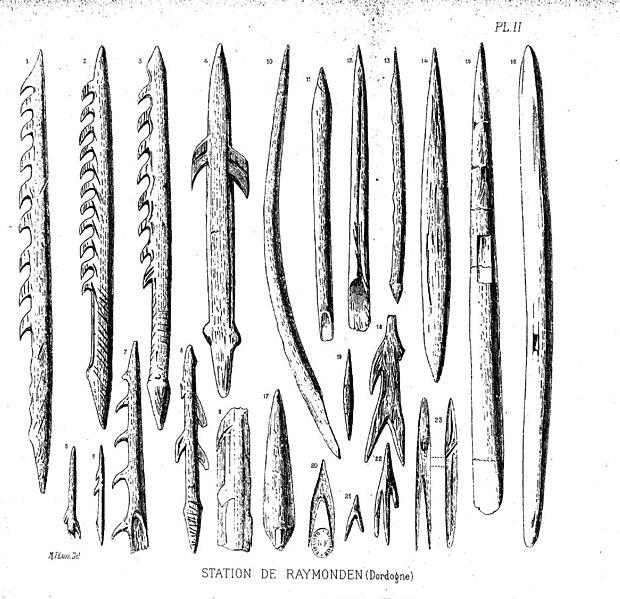

The sequence of modern Homo sapiens technological change in the Later Stone Age has been thoroughly dated and labeled by researchers working in Europe. Among them, the Gravettian tradition of 33,000 years to 21,000 years ago is associated with most of the known curvy female figurines, often assumed to be “Venus” figures. Hunting technology also advanced in this time with the first known boomerang, atlatl (spear thrower), and archery. The Magdalenian tradition spread from 17,000 to 12,000 years ago. This culture further expanded on fine bone tool work, including barbed spearheads and fishhooks (Figure 13.16).

Among the many European sites dating to the Later Stone Age, the famous cave art sites deserve mention. Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave in southern France dates to separate Aurignacian occupations 31,000 years ago and 26,000 years ago. Over a hundred art pieces representing 13 animal species are preserved, from commonly depicted deer and horses to rarer rhinos and owls. Another French cave with art is Lascaux, which is several thousand years younger at 17,000 years ago in the Magdalenian period. At this site, there are over 6,000 painted figures on the walls and ceiling (Figure 13.17). Scaffolding and lighting must have been used to make the paintings on the walls and ceiling deep in the cave. Overall, visiting Lascaux as a contemporary must have been an awesome experience: trekking deeper in the cave lit only by torches giving glimpses of animals all around as mysterious sounds echoed through the galleries.

Special Topic: Cannibalism and Culture - Mortuary Practices in Modern Homo sapiens

Within a 2017 publication in the Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, Saladié and Rodríguez-Hidalgo bring light to traces of early cannibalism in western Eurasia, arguing that context-specific cannibalistic practices were present throughout the Pleistocene and increased notably from the end of the Upper Palaeolithic and onward (Saladié & Rodriguez-Hidalgo, 2017). While early hominins and Neandertals are recognized in this research, the authors highlight the presence of these mortuary practices in a cluster of Homo sapien sites. More recent research uncovers similar findings that back these claims as well, where human bones in Herto Ethiopia, Maszycka Cave Poland, and Gough’s Cave in the United Kingdom show anthropogenic defleshing and other modifications which have been interpreted as cannibalism (Pobiner, Et al. 2023). These findings suggest that cannibalistic behaviours formed a recurring aspect of modern human behaviour in certain ecological and cultural contexts.

A significant example comes from the Neolithic levels of Fontbrégua Cave in southeastern France, where Paola Villa and colleagues compared clusters of human bones with the remains of wild and domestic animals from the same sediments. The study found that human bodies were butchered, processed, and most likely eaten in a way that parallels animal carcass treatment, including the placement and timing of cut marks, dismemberment sequences, and perimortem fractures to open marrow cavities (Villa, Et al. 1986). As the assemblage comes from a primary depositional context with pristine preservation and careful excavation, the authors suggest that cannibalism is the only satisfactory explanation for the pattern of cut marks and breakage seen on the human bones.

More recent work has furthered this hypothesis for Late Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens, especially in Magdalenian contexts. In a 2023 study, researchers combined archeological and genetic evidence from fifty-nine Magdalenian sites, concluding that this specific culture shows an unusually high frequency of cannibalistic cases compared to earlier and later hominin groups; so much so that they identify “primary burial and cannibalism” as the two main mortuary expressions (Marsh & Bello, 2023). Additionally, new analyses from Maszycka Cave in Poland have described cut and broken human bones in patterns consistent with human consumption, reinforcing this cannibalism hypothesis (Marginedas & Saladié, 2025). Together, these studies suggest that for some Magdalenian groups, mortuary cannibalism was a habitual way of disposing of the dead, not just a one-off crisis response. At the same time, researchers emphasize that not every modified skeleton indicates blatant consumption of the dead and that ritual or symbolic perspectives must also be considered. Previously noted in chapter eleven, Ullrich’s survey of European mortuary practices presents frequent manipulations of corpses from the Palaeolithic through the Hallstatt period. Said manipulations include cut marks, dismemberment, skull fracturing, and marrow extraction (Ullrich, 2005, p. 258), which Ullrich interprets as cannibalistic rites embedded in cult ceremonies rather than everyday subsistence. In the author’s view, some Palaeolithic groups may have believed that consuming members of their community allowed them to take on the strengths,

abilities, or even mental aspects of their dead member; the act of cannibalism may have functioned as a form of appropriating physical and mental powers rather than simply obtaining calories. With that, Neolithic assemblages show how careful taphonomic work can distinguish cuts linked to interpersonal violence from those associated with systemic butchery (Marginedas & Saladié, 2025). The findings seek to highlight that some Homo sapiens populations combined ritual, mortuary, and nutritional motives when processing human remains.

These past and contemporary findings are significant for future anthropology students as they shed light on biological anthropology methodology and interpretation. Archaeologists are able to distinguish between occasions when humans were handled like any other carcass and times when they were handled in more symbolic ways thanks to factors like cut mark orientation, the timing of bone breakage, and direct comparison with animal remains. Readers interested in exploring this topic further should investigate the context-specific motivations for cannibalism, like nutritional stress, warfare, funerary sites, or ritual power appropriation.

Similar archeological techniques have been used to explore behaviours of cannibalism among Indigenous Huron-Wendat populations in 1651 Canada, where human bones exhibit cutmarks, perimortem fractures, and thermal modifications (Spence & Jackson, 2014). These shared taphonomic signatures across continents reveal recurring practices under ecological stress, bridging prehistoric Europe to North American contexts. Engaging with such analytical techniques opens up new ways that archeologists and anthropologists can investigate the variability in human behaviour, from nutritional crises to mortuary rituals.

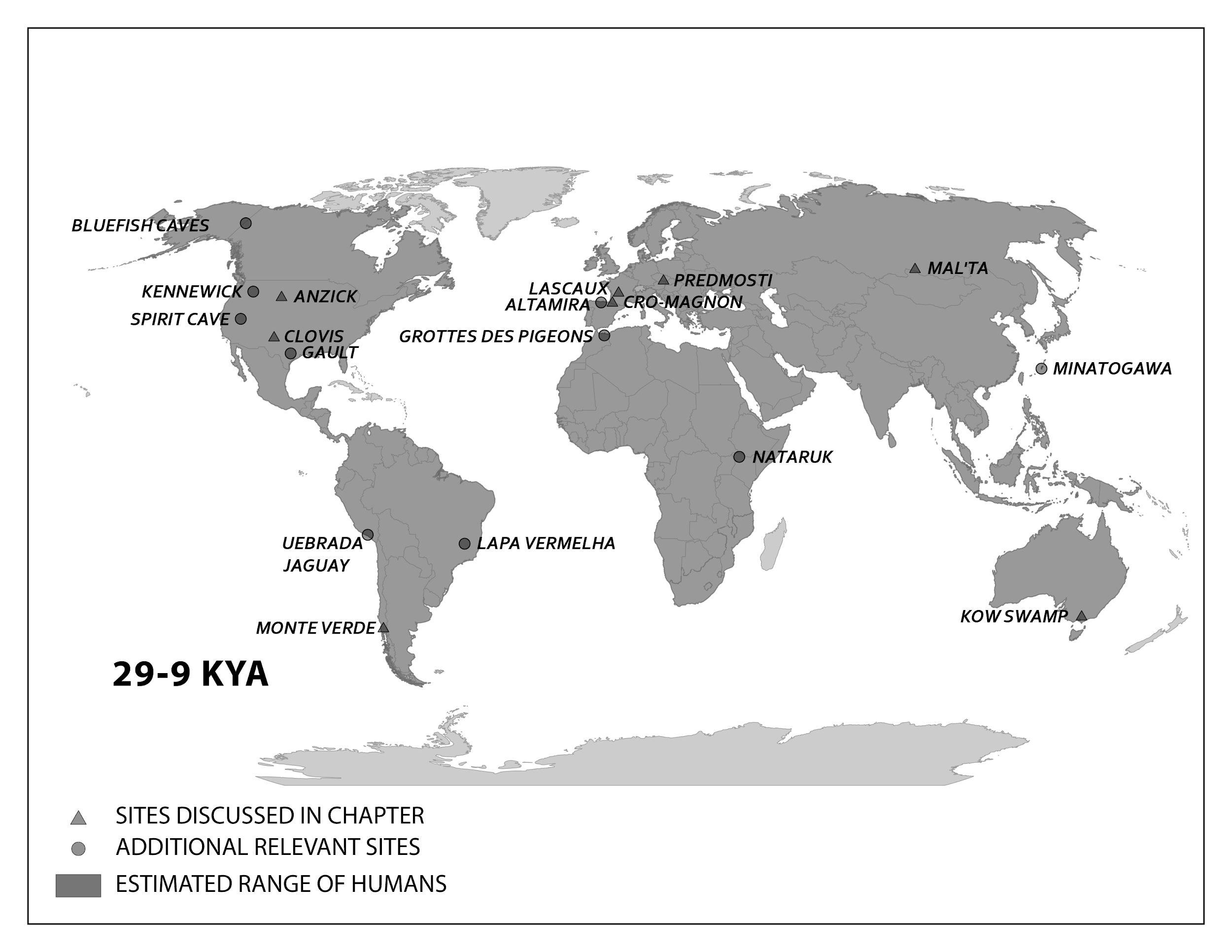

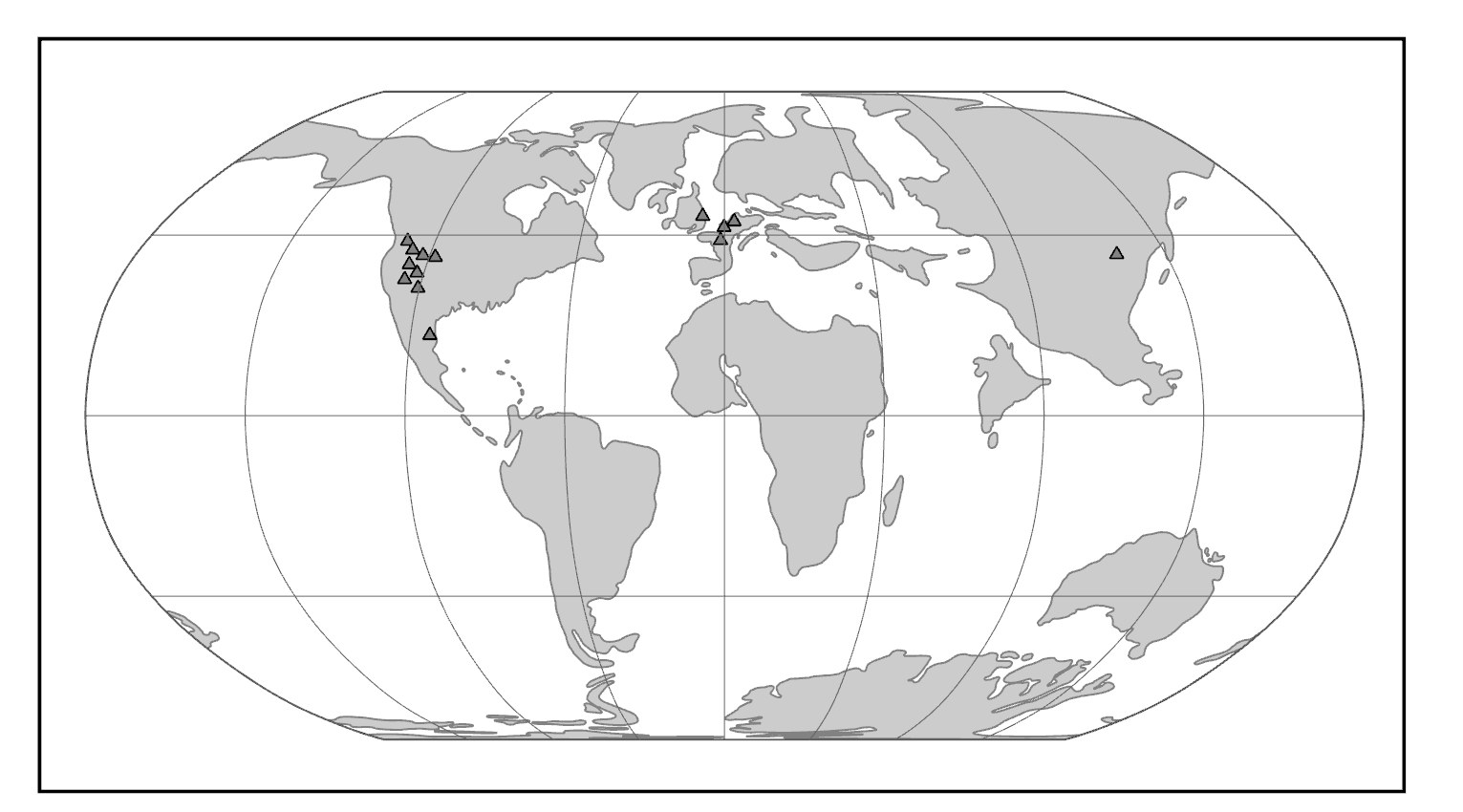

Peopling of the Americas

By 25,000 years ago, our species was the only member of Homo left on Earth. Gone were the Neanderthals, Denisovans, Homo naledi, and Homo floresiensis. The range of modern Homo sapiens kept expanding eastward into—using the name given to this area by Europeans much later—the Western Hemisphere. This section will address what we know about the peopling of the Americas, from the first entry to these continents to the rapid spread of Indigenous Americans across its varied environments.

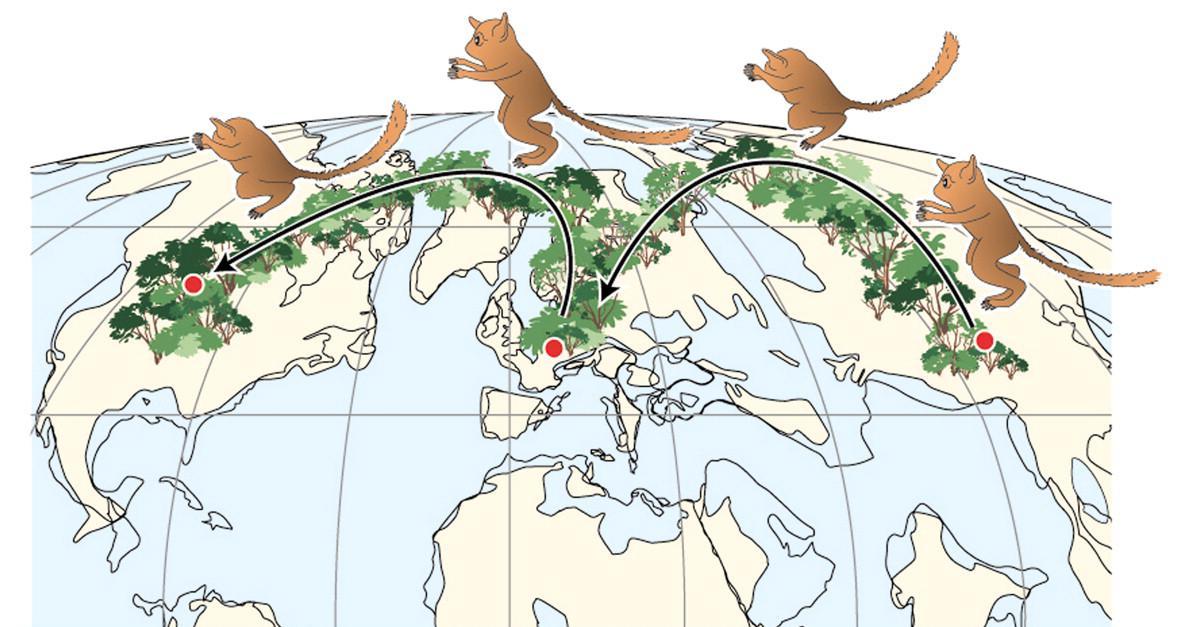

While evidence points to an ancient land bridge called Beringia that allowed people to cross from what is now northeastern Siberia into modern-day Alaska, what people did to cross this land bridge is still being investigated. For most of the 20th century, the accepted theory was the Ice-Free Corridor model. It stated that northeast Asians (East Asians and Siberians) first expanded across Beringia inland through a passage between glaciers that opened into the western Great Plains of the United States, just east of the Rocky Mountains, around 13,000 years ago (Swisher et al. 2013). While life up north in the cold environment would have been harsh, migrating birds and an emerging forest might have provided sustenance as generations expanded through this land (Potter et al. 2018).

However, in recent decades, researchers have accumulated evidence against the Ice-Free Corridor model. Archaeologist K. R. Fladmark (1979) brought the alternate Coastal Route model into the archaeological spotlight; researcher Jon M. Erlandson has been at the forefront of compiling support for this theory (Erlandson et al. 2015). The new focus is the southern edge of the land bridge instead of its center: About 16,000 years ago, members of our species expanded along the coastline from northeast Asia, east through Beringia, and south down the Pacific Coast of North America while the inland was still sealed off by ice. The coast would have been free of ice at least part of the year, and many resources would have been found there, such as fish (e.g., salmon), mammals (e.g., whales, seals, and otters), and plants (e.g., seaweed).

South through the Americas

When the first modern Homo sapiens reached the Western Hemisphere, the spread through the Americas was rapid. Multiple migration waves crossed from North to South America (Posth et al. 2018). Our species took advantage of the lack of hominin competition and the bountiful resources both along the coasts and inland. The Americas had their own wide array of megafauna, which included woolly mammoths (Figure 13.20), mastodons, camels, horses, ground sloths, giant tortoises, and—a favorite of researchers—a two-meter-tall beaver. The reason we cannot see these amazing animals today may be that resources gained from these fauna were crucial to the survival for people over 12,000 years ago (Araujo et al. 2017). Several sites are notable for what they add to our understanding of the distant past in the Americas, including interactions with megafauna and other elements of the environment.

A 2019 discovery may allow researchers to improve theories about the peopling of the Americas. In White Sands National Park, New Mexico, 60 human footprints have been astonishingly dated to around 22,000 years ago (Bennett et al. 2021). This date and location do not match either the Ice-Free Corridor or Coastal Route models. Researchers are now working to verify the find and adjust previous models to account for the new evidence. This groundbreaking find is sparking new theories; it is another example of the fast pace of research performed on our past.

Monte Verde is a landmark site that shows that the human population had expanded down the whole vertical stretch of the Americas to Chile by 14,600 years ago. The site has been excavated by archaeologist Tom D. Dillehay and his team (2015). The remains of nine distinct edible species of seaweed at the site shows familiarity with coastal resources and relates to the Coastal Route model by showing a connection between the inland people and the sea.

Named after the town in New Mexico, the Clovis stone-tool style is the first example of a widespread culture across much of North America, between 13,400 and 12,700 years ago (Miller, Holliday, and Bright 2013). Clovis points were fluted with two small projections, one on each end of the base, facing away from the head (Figure 13.21). The stone points found at this site match those found as far as the Canadian border and northern Mexico, and from the west coast to the east coast of the United States. Fourteen Clovis sites also contained the remains of mammoths or mastodons, suggesting that hunting megafauna with these points was an important part of life for the Clovis people. After the spread of the Clovis style, it diversified into several regional styles, keeping some of the Clovis form but also developing their own unique touches.

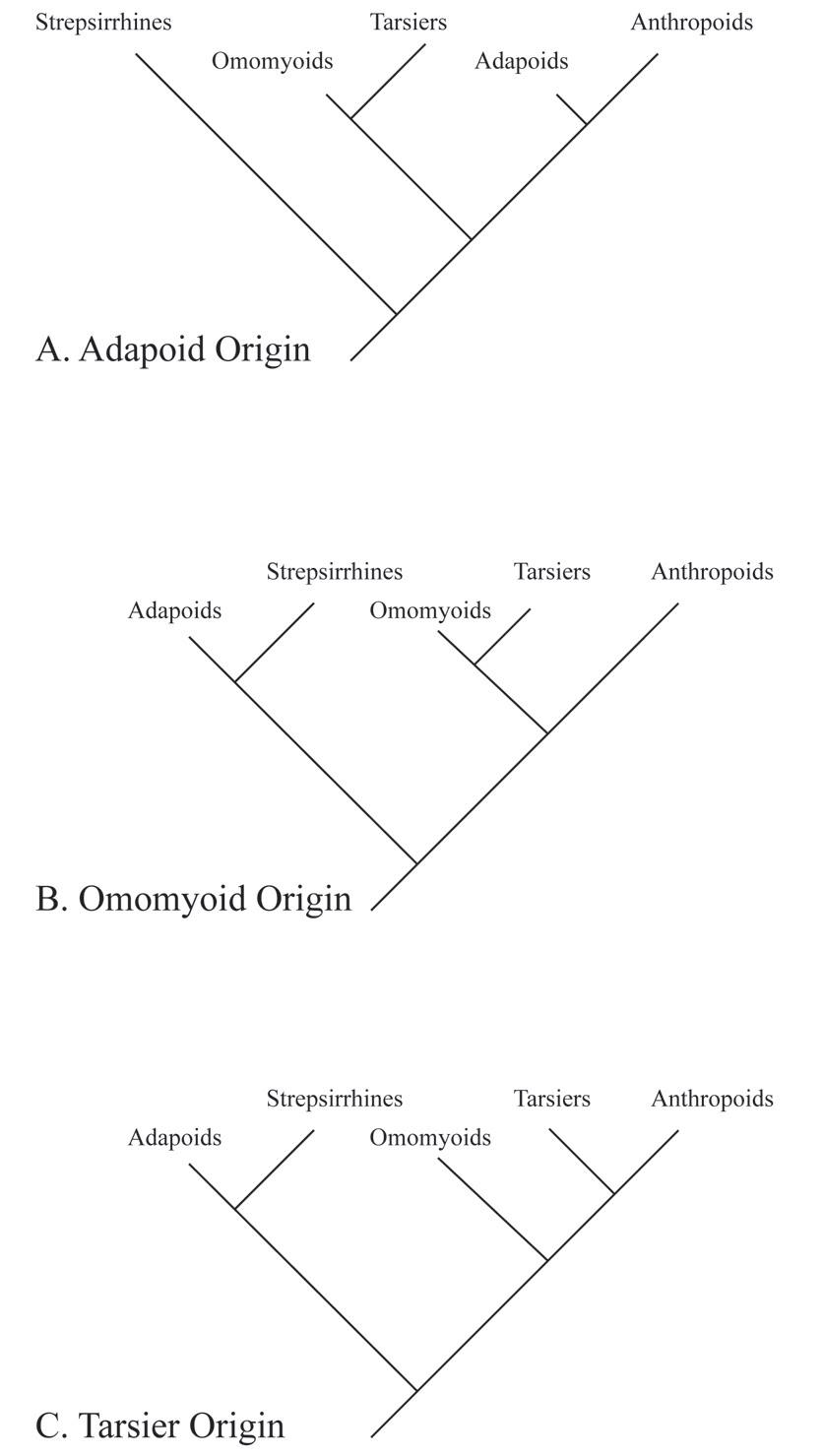

The Big Picture: The Assimilation Hypothesis

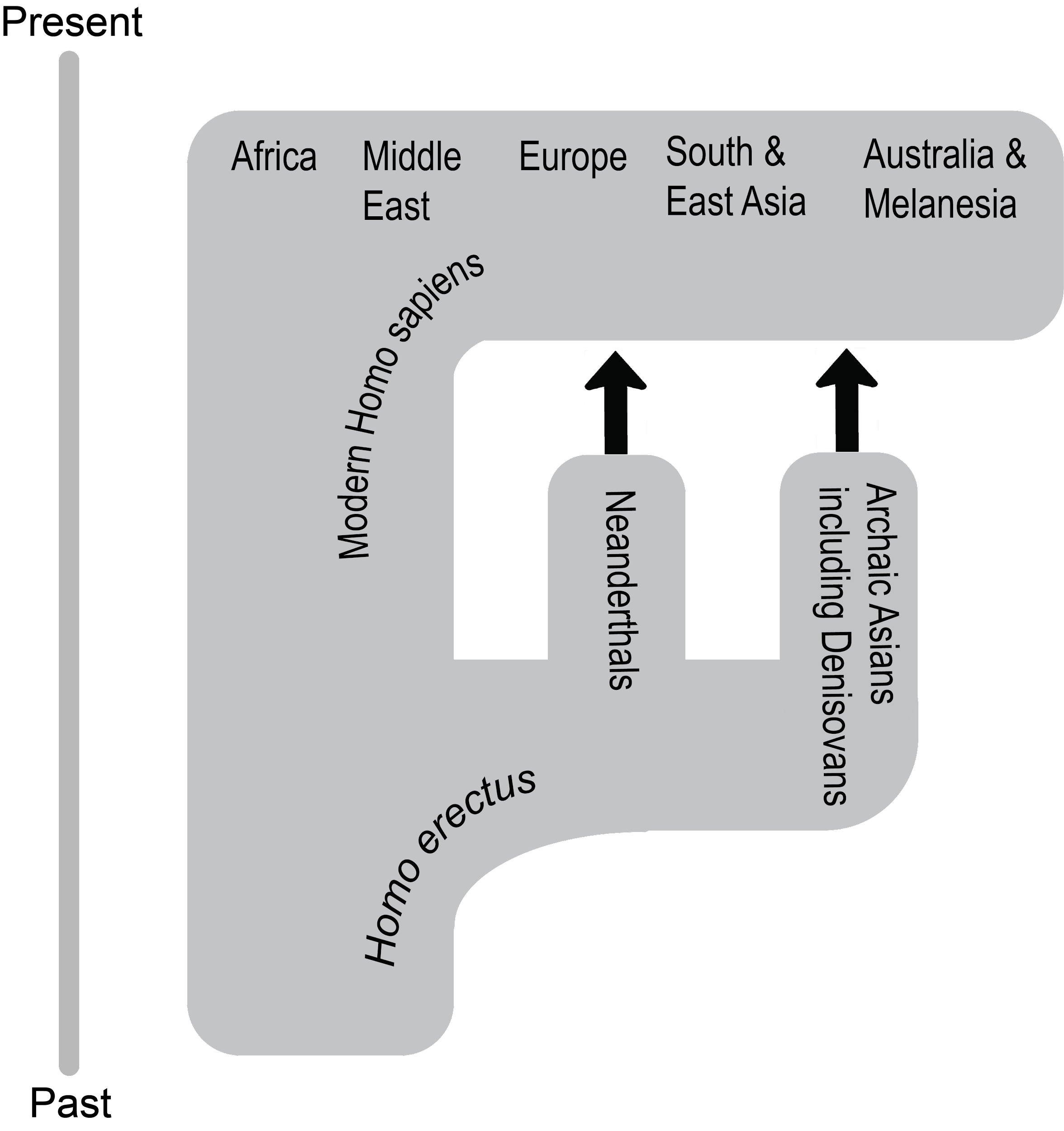

How do researchers make sense of all of these modern Homo sapiens discoveries that cover over 300,000 years of time and stretch across every continent except Antarctica? How was modern Homo sapiens related to archaic Homo sapiens?

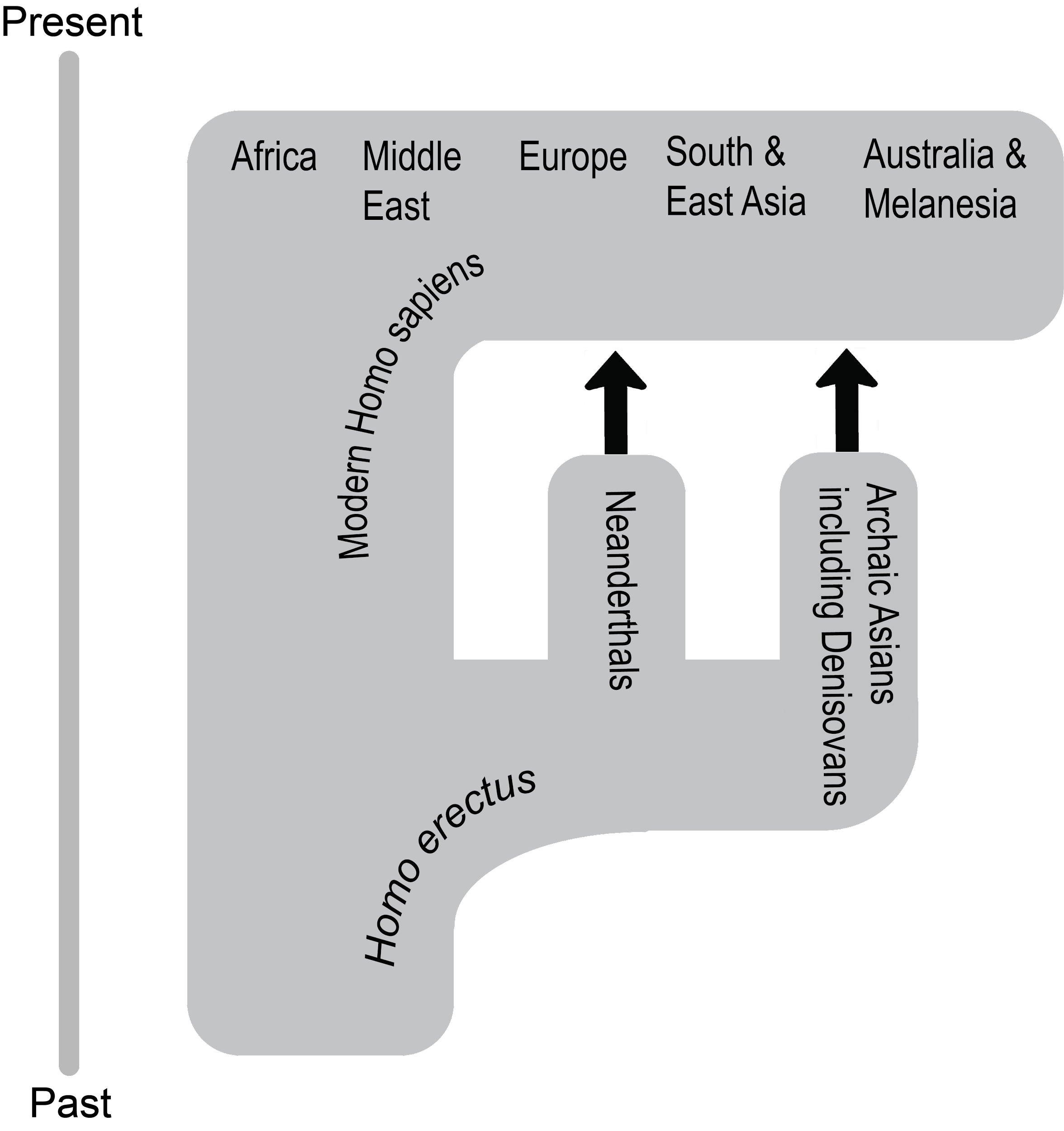

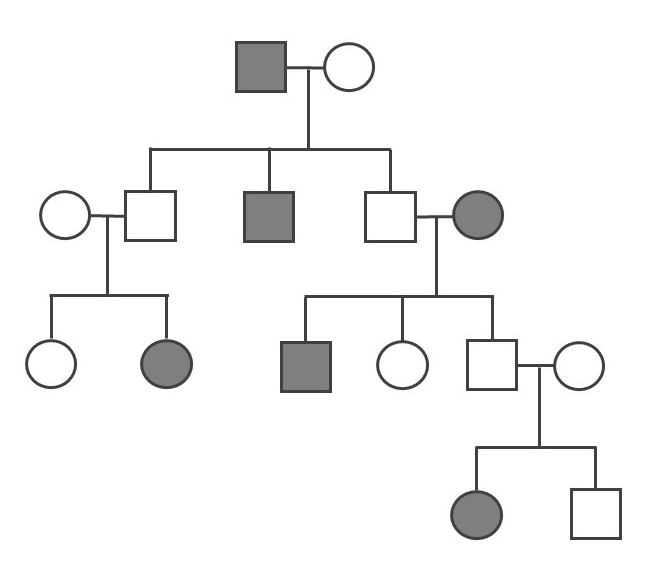

The Assimilation hypothesis proposes that modern Homo sapiens evolved in Africa first and expanded out but also interbred with the archaic Homo sapiens they encountered outside Africa (Figure 13.22). This hypothesis is powerful since it explains why Africa has the oldest modern human fossils, why early modern humans found in Europe and Asia bear a resemblance to the regional archaics, and why traces of archaic DNA can be found in our genomes today (Dannemann and Racimo 2018; Reich et al. 2010; Reich et al. 2011; Slatkin and Racimo 2016; Smith et al. 2017; Wall and Yoshihara Caldeira Brandt 2016).

While researchers have produced a model that satisfies the data, there are still a lot of questions for paleoanthropologists to answer regarding our origins. What were the patterns of migration in each part of the world? Why did the archaic humans go extinct? In what ways did archaic and modern humans interact? The definitive explanation of how our species started and what our ancestors did is still out there to be found. You are now in a great place to welcome the next discovery about our distant past—maybe you’ll even contribute to our understanding as well.

The Chain Reaction of Agriculture

While it may be hard to imagine today, for most of our species’ existence we were nomadic: moving through the landscape without a singular home. Instead of a refrigerator or pantry stocked with food, we procured nutrition and other resources as needed based on what was available in the environment. This section gives an overview of how the foraging lifestyle enabled the expansion of our species and how the invention of a new way of life caused a chain reaction of cultural change.

The Foraging Tradition

There are a variety of possible subsistence strategies, or methods of finding sustenance and resources. To understand our species is to understand the subsistence strategy of foraging, or the search for resources in the environment. While most (but not all) humans today live in cultures that practice agriculture (whereby we greatly shape the environment to mass produce what we need), we have spent far more time as nomadic foragers than as settled agriculturalists. As such, it has been suggested that our traits have evolved to be primarily geared toward foraging. For instance, our efficient bipedalism allows persistence-hunting across long distances as well as movement from resource to resource.

How does human foraging, also known as hunting and gathering, work? Anthropologists have used all four fields to answer this question (see Ember n.d.). Typically, people formed bands, or kin-based groups of around 50 people or less (rarely over 100). A band’s organization would be egalitarian, with a flexible hierarchy based on an individual’s age, level of experience, and relationship with others. Everyone would have a general knowledge of the skills assigned to their gender roles, rather than specializing in different occupations. A band would be able to move from place to place in the environment, using knowledge of the area to forage (Figure 13.23). In varied environments—from savannas to tropical forests, deserts, coasts, and the Arctic circle—people found sustenance needed for survival.

Humans made extensive use of the foraging subsistence strategy, but this lifestyle did have limitations. The ease of foraging depended on the richness of the environment. Due to the lack of storage, resources had to be dependably found when needed. While a bountiful environment would require just a few hours of foraging a day and could lead to a focus on one location, the level and duration of labor increased greatly in poor or unreliable environments. Labor was also needed to process the acquired resources, which contributed to the foragers’ daily schedule (Crittenden and Schnorr 2017).

The adaptations to foraging found in modern Homo sapiens may explain why our species became so successful both within Africa and in the rapid expansion around the world. Overcoming the limitations, each generation at the edge of our species’s range would have found it beneficial to expand a little further, keeping contact with other bands but moving into unexplored territory where resources were more plentiful. The cumulative effect would have been the spread of modern Homo sapiens across continents and hemispheres.

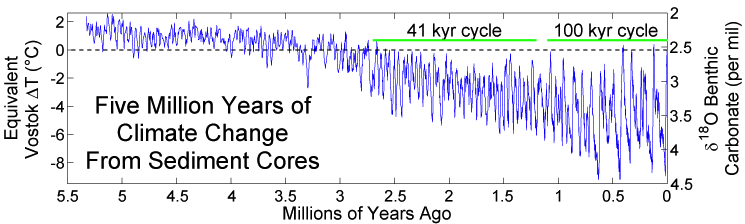

Why Agriculture?

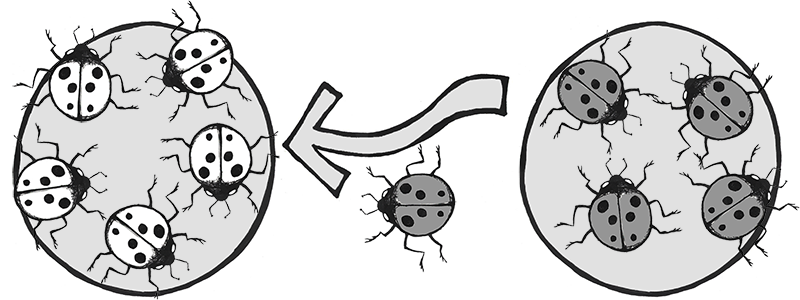

After hundreds of thousands of years of foraging, some groups of people around 12,000 years ago started to practice agriculture. This transition, called the Neolithic Revolution, occurred at the start of the Holocene epoch. While the reasons for this global change are still being investigated, two likely co-occurring causes are a growing human population and natural global climate change.