8 Primate Evolution

Beth Shook; Ph.D.; Lara Braff; Katie Nelson; Kelsie Aguilera; and M.A.

Jonathan M. G. Perry, Ph.D., Western University of Health Sciences

Stephanie L. Canington, Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania

This chapter is a revision from “Chapter 8: Primate Evolution” by Jonathan M. G. Perry and Stephanie L. Canington. In Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology, first edition, edited by Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera, and Lara Braff, which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the major trends in primate evolution from the origin of primates to the origin of our own species.

- Learn about primate adaptations and how they characterize major primate groups.

- Discuss the kinds of evidence that anthropologists use to find out how extinct primates are related to each other and to living primates.

- Recognize how the changing geography and climate of Earth have influenced where and when primates have thrived or gone extinct.

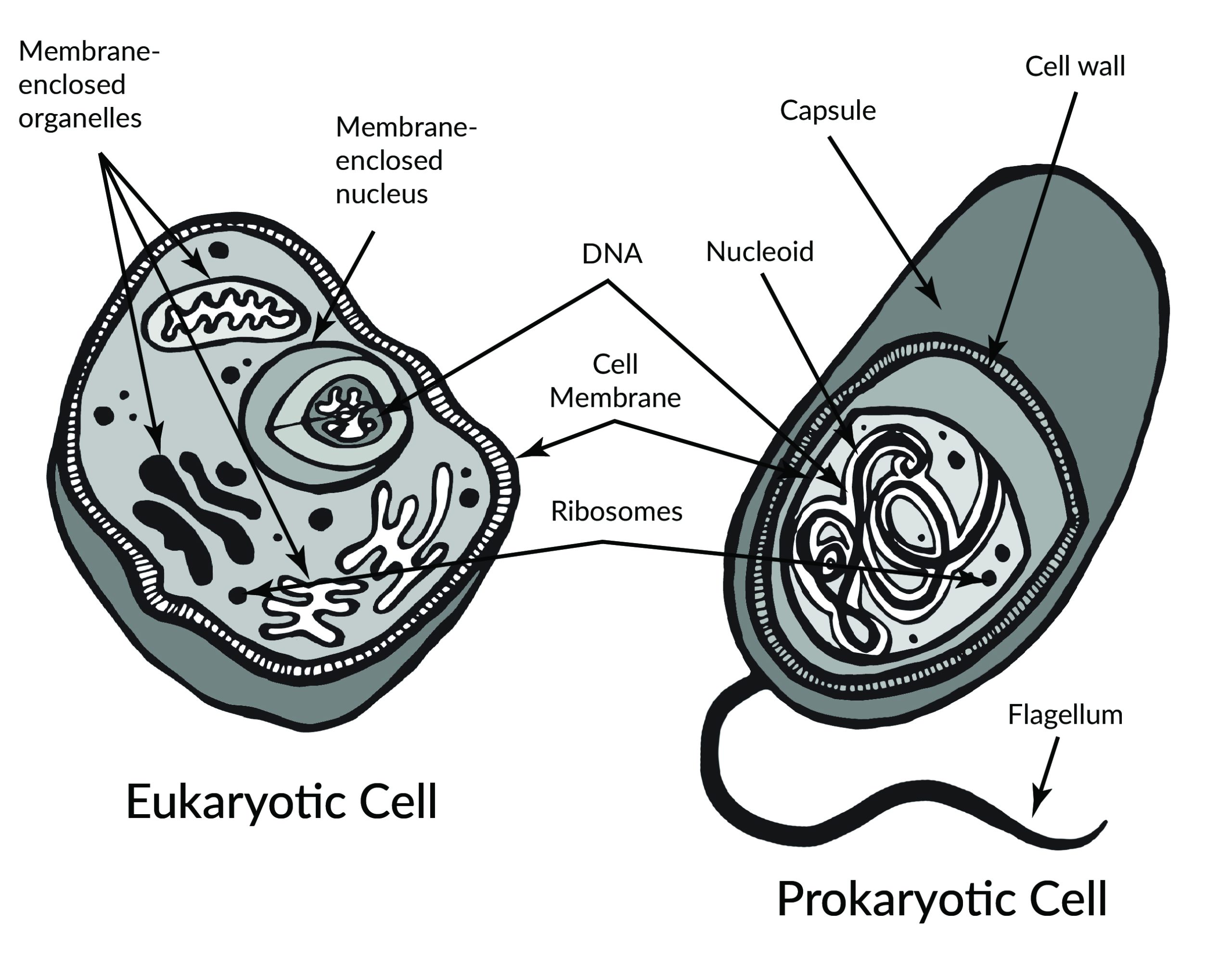

The first fifty million years of primate evolution was a series of adaptive radiations leading to the diversification of the earliest lemurs, monkeys, and apes. The primate story begins in the canopy and understory of conifer-dominated forests, with our small, furtive ancestors subsisting at night, beneath the notice of day-active dinosaurs.

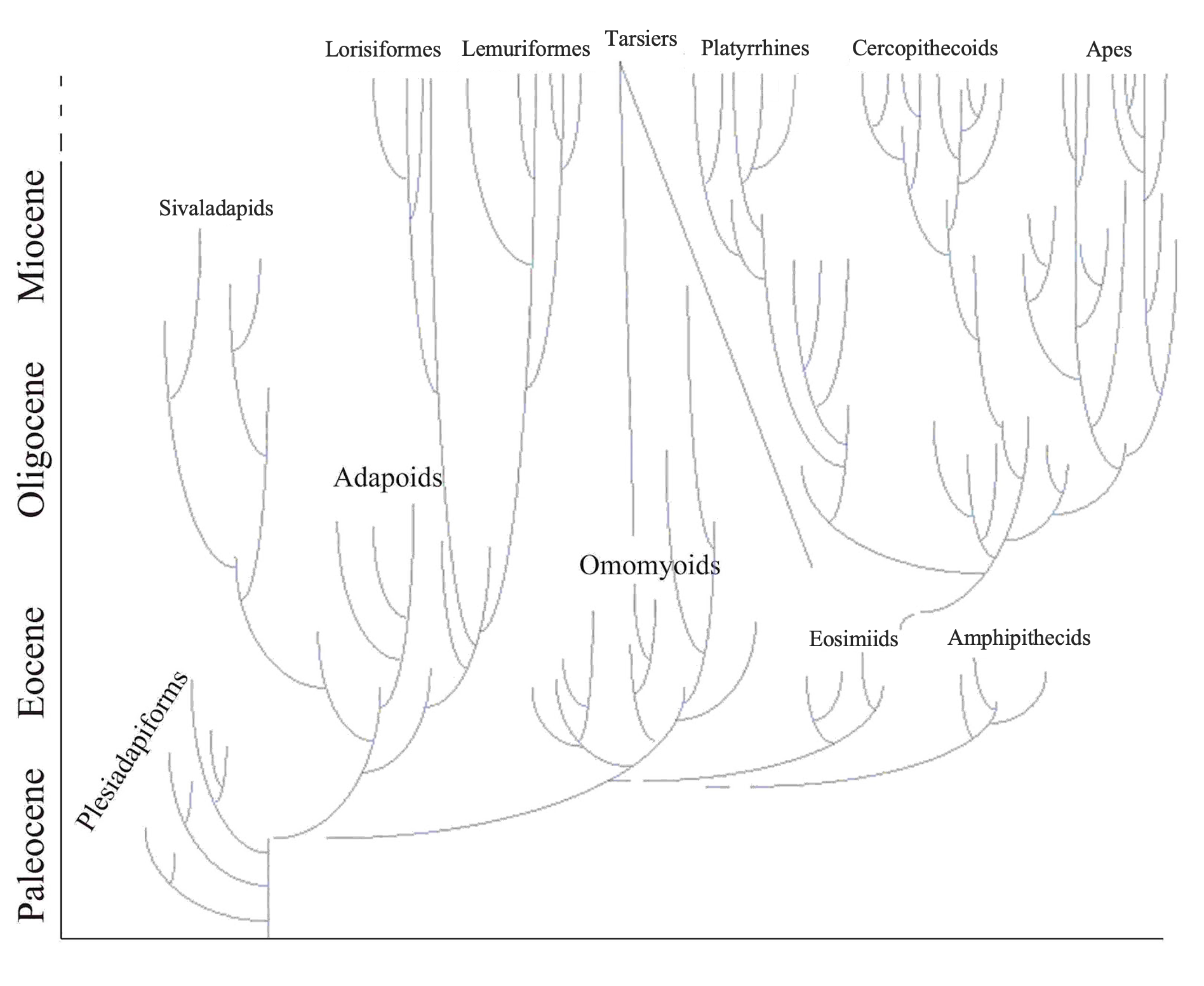

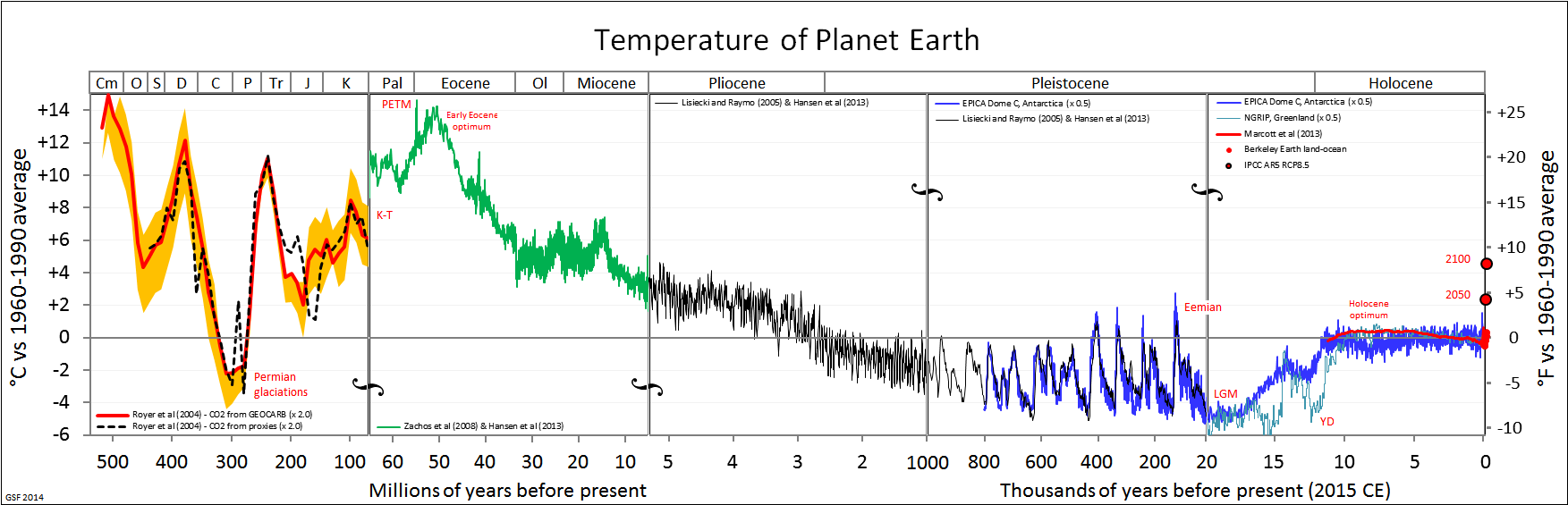

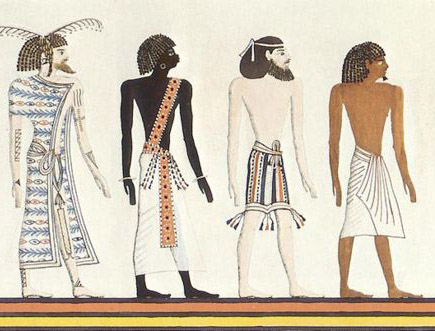

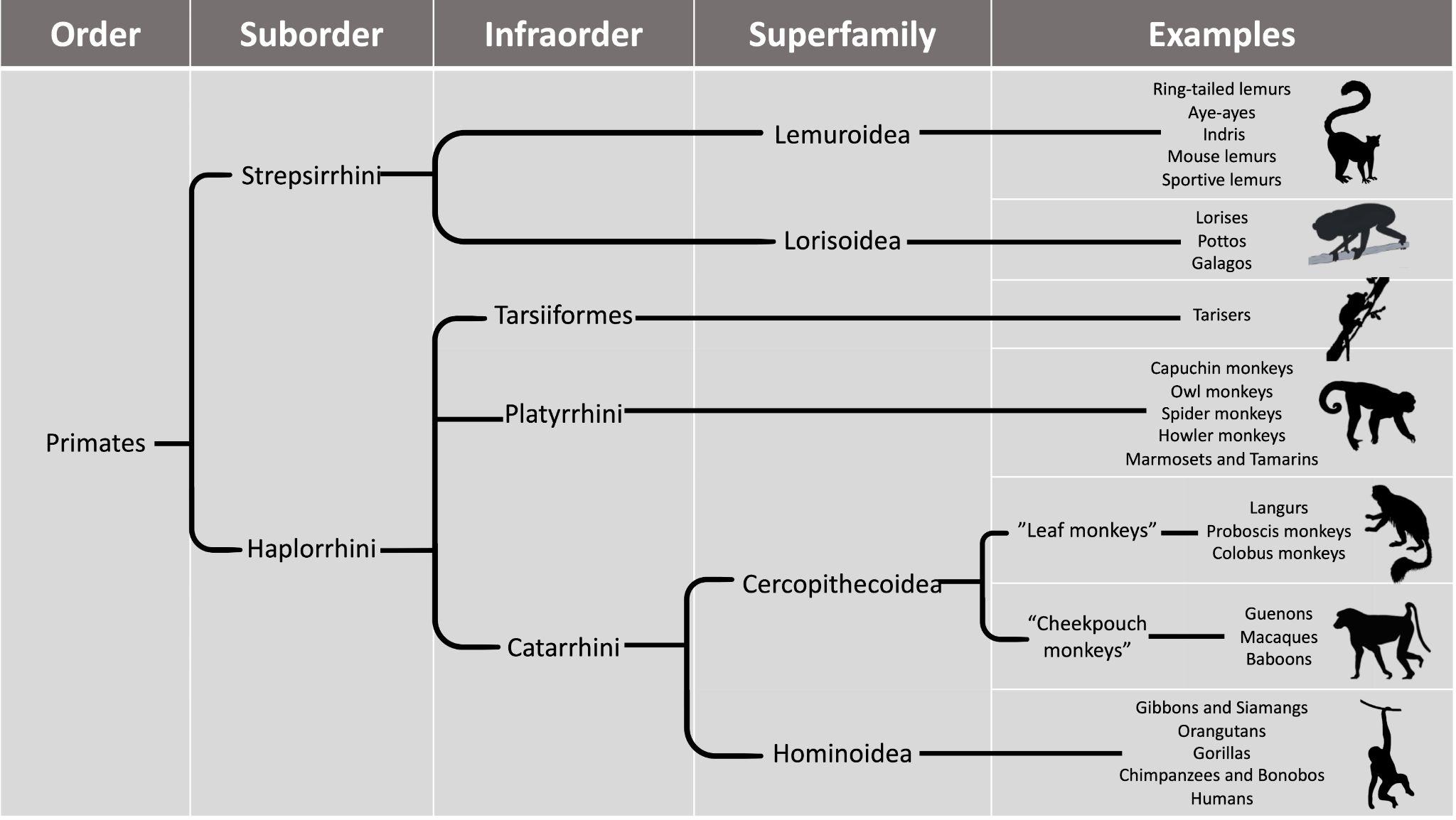

From the ancient plesiadapiforms (archaic primates) to the earliest groups of true primates (euprimates) (Bloch and Boyer 2002), the origin of our own order is characterized by the struggle for new food sources and microhabitats in the arboreal setting. Climate change forced major extinctions as the northern continents became increasingly dry, cold, and seasonal and as tropical rainforests gave way to deciduous forests, woodlands, and eventually grasslands. Lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers—once diverse groups containing many species—became rare, except for lemurs in Madagascar, where there were no anthropoid competitors and perhaps few predators. Meanwhile, anthropoids (monkeys and apes) likely emerged in Asia and then dispersed across parts of the northern hemisphere, Africa, and ultimately South America. The movement of continents, shifting sea levels, and changing patterns of rainfall and vegetation contributed to the developing landscape of primate biogeography, morphology, and behavior. Today’s primates provide modest reminders of the past diversity and remarkable adaptations of their extinct relatives. This chapter explores the major trends in primate evolution from the origin of the Order Primates to the beginnings of our own lineage, providing a window into these stories from our ancient past.

Major Hypotheses About Primate Origins

For many groups of mammals, there is a key feature that led to their success. A good example is powered flight in bats. Primates lack a feature like this (see Chapter 5). Instead, if there is something unique about primates, it is probably a group of features rather than one single thing. Because of this, anthropologists and paleontologists struggle to describe an ecological scenario that could explain the rise and success of our own order. Three major hypotheses have been advanced to consider the origin of primates and to explain what makes our order distinct among mammals (Figure 8.1); these are described below.

Arboreal Hypothesis

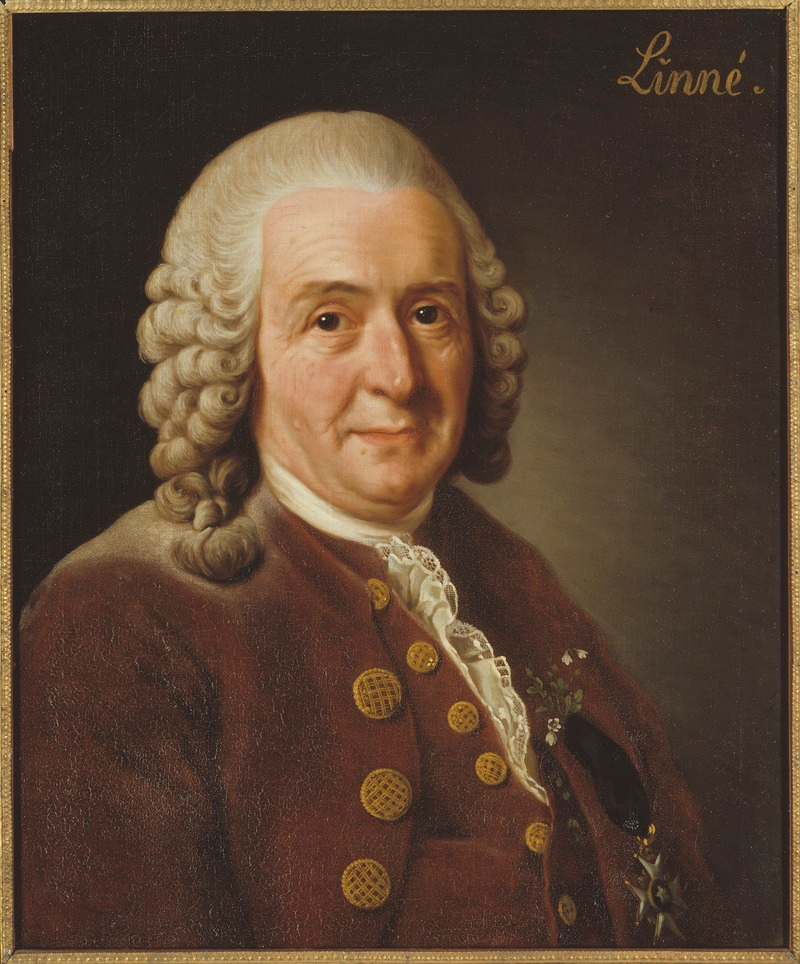

In the 1800s, many anthropologists viewed all animals in relation to humans. That is, animals that were more like humans were considered to be more “advanced” and those lacking humanlike features were considered more “primitive.” This way of thinking was particularly obvious in studies of primates. A more modern way of referring to members of a group that lack certain evolutionary innovations seen in other members is to call them plesiomorphic (literally “anciently shaped”). The state of their morphological features is sometimes referred to as ancestral traits.

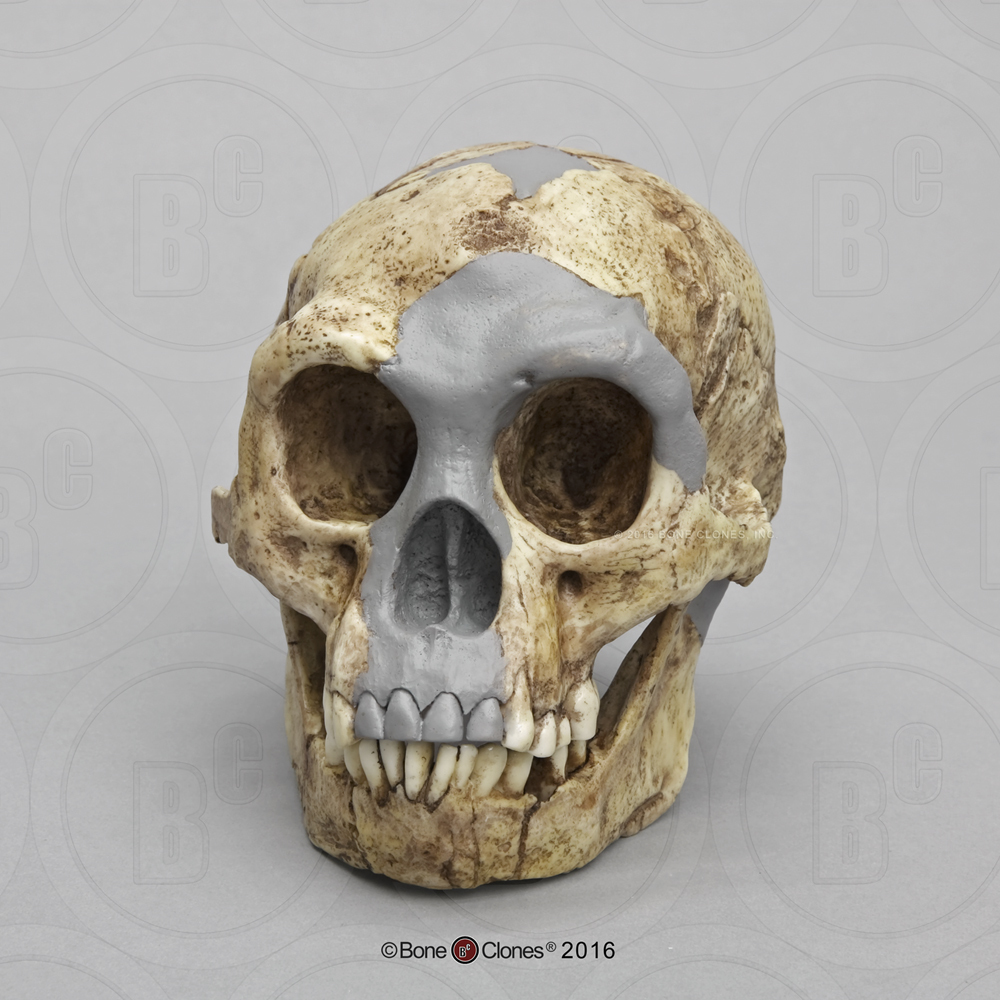

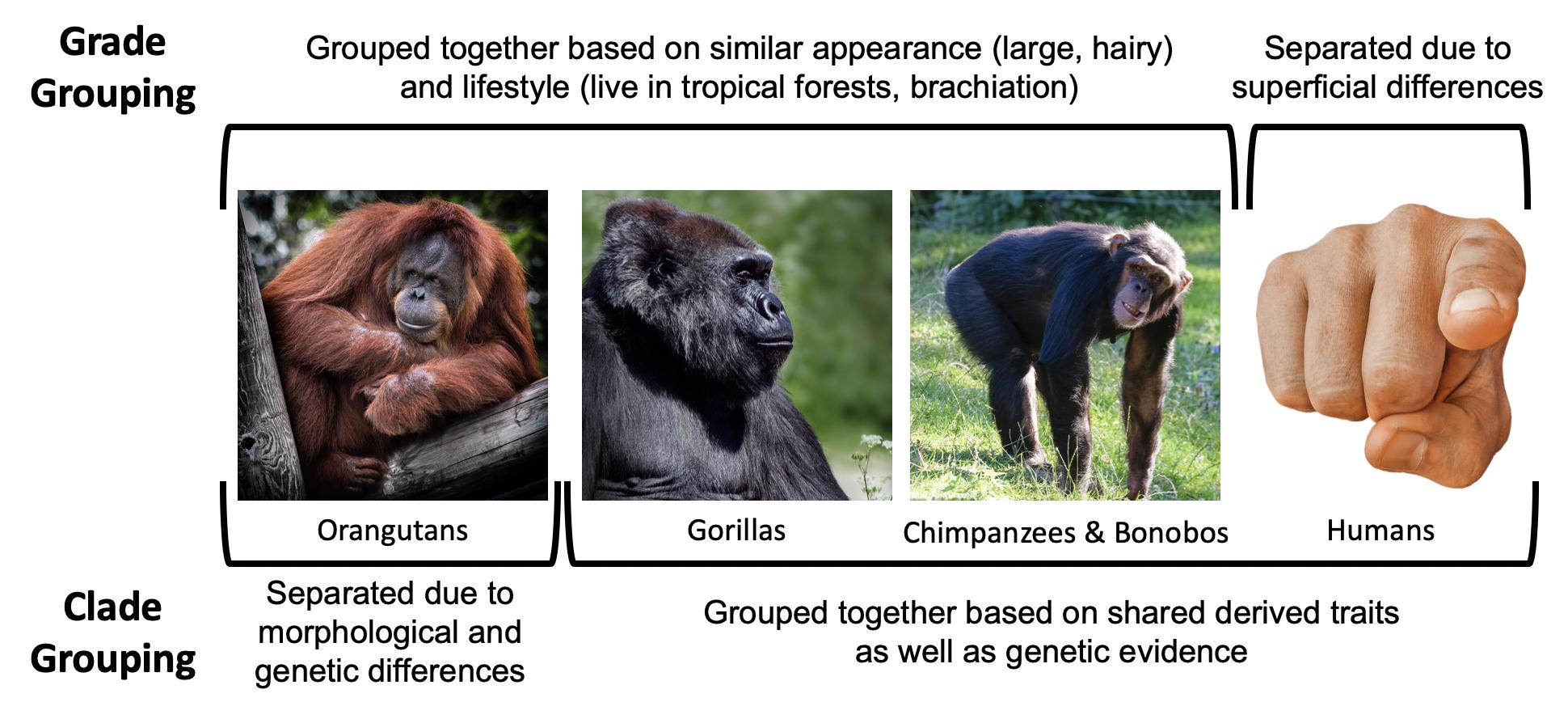

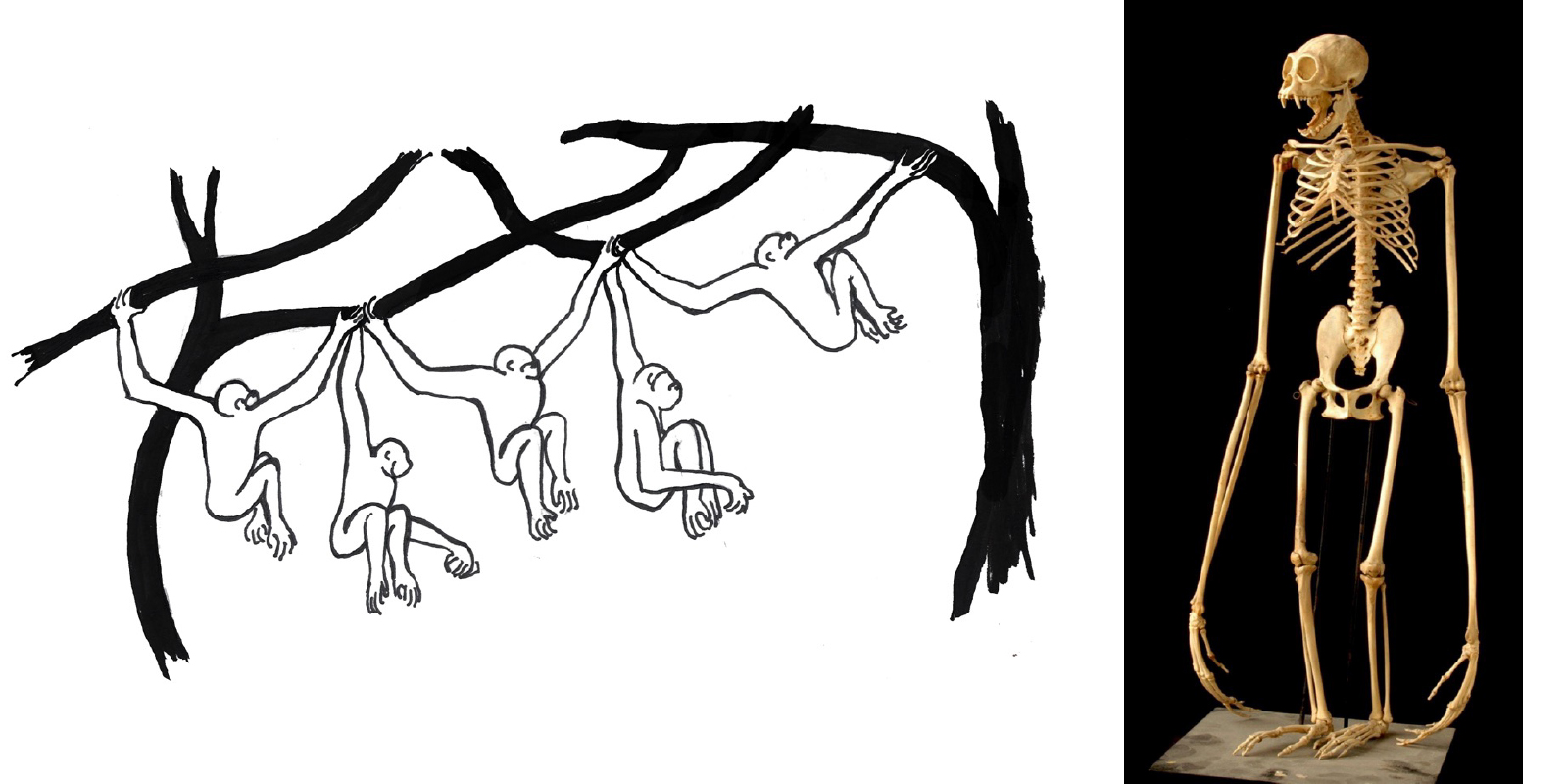

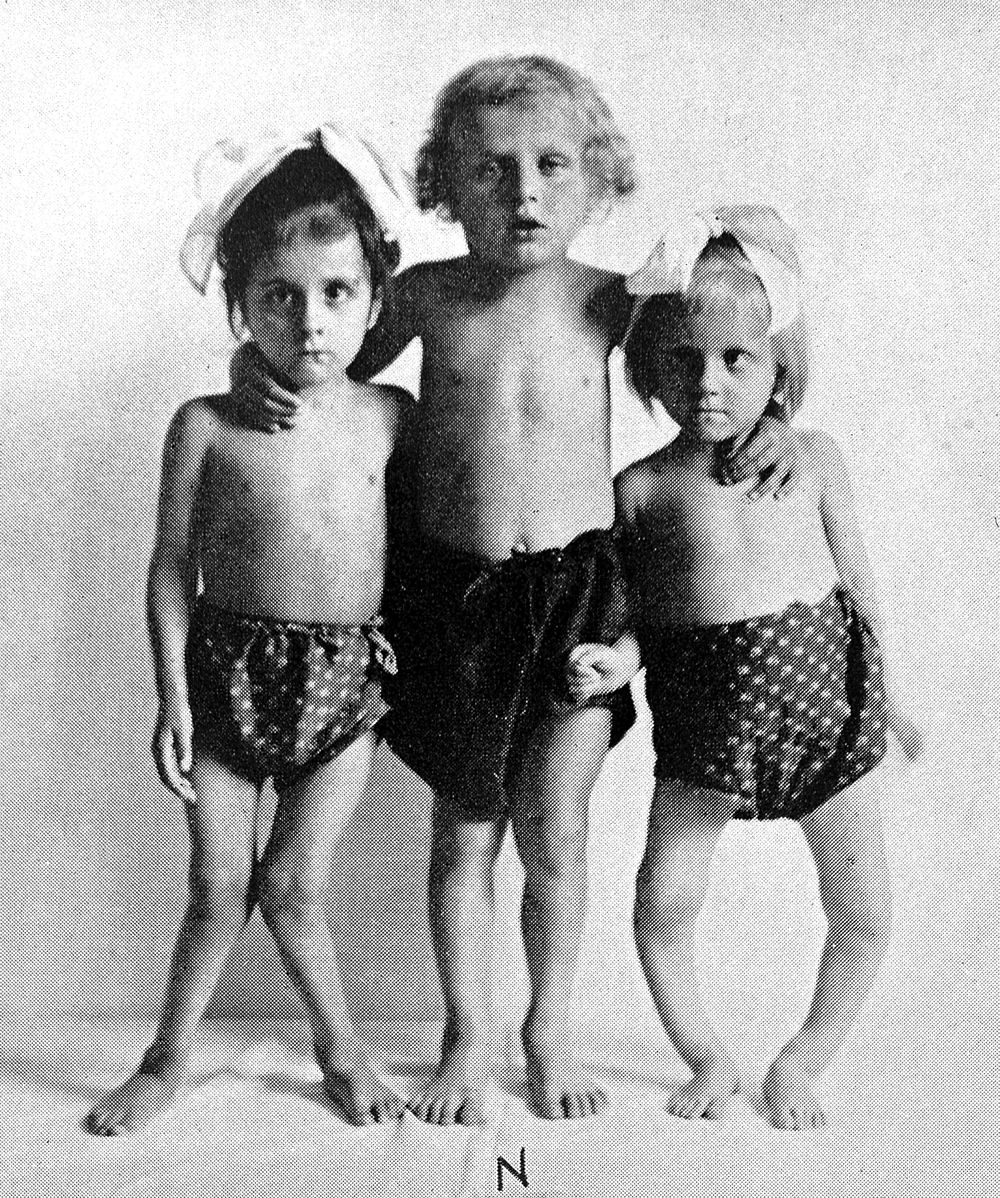

Thus, when anthropologists sought features that separate primates from other mammals, they focused on features that were least developed in lemurs and lorises, more developed in monkeys, and most developed in apes (Figure 8.2). Frederic Wood Jones, one of the leading anatomist-anthropologists of the early 1900s, is usually credited with the Arboreal Hypothesis of primate origins (Jones 1916). This hypothesis holds that many of the features of primates evolved to improve locomotion in the trees; this way of getting around is referred to as arboreal. For example, the grasping hands and feet of primates are well suited to gripping tree branches of various sizes and our flexible joints are good for reorienting the extremities in many different ways. A mentor of Jones, Grafton Elliot Smith, had suggested that the reduced olfactory system, acute vision, and forward-facing eyes of primates are adaptations for making accurate leaps and bounds through a complex, three-dimensional canopy (Smith 1912). The forward orientation of the eyes in primates causes the visual fields to overlap, enhancing depth perception, especially at close range. Evidence to support this hypothesis includes the facts that many extant primates are arboreal, and the plesiomorphic members of most primate groups are dedicated arborealists. The Arboreal Hypothesis was well accepted by most anthropologists at the time and for decades afterward.

Visual Predation Hypothesis

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Matt Cartmill studied and tested the idea that the characteristic features of primates evolved in the context of arboreal locomotion. Cartmill noted that squirrels climb trees (and even vertical walls) very effectively, even though they lack some of the key adaptations of primates. As members of the Order Rodentia, squirrels also lack the hand and foot anatomy of primates. They have claws instead of flattened nails and their eyes face more laterally than those of primates. Cartmill reasoned that there must be some other explanation for the unique traits of primates. He noted that some nonarboreal animals share at least some of these traits with primates; for example, cats and predatory birds have forward-facing eyes that enable visual field overlap. Cartmill suggested that the unique suite of features in primates is an adaptation to detecting insect prey and guiding the hands (or feet) to catch insects (Cartmill 1972). His hypothesis emphasizes the primary role of vision in prey detection and capture; it is explicitly comparative, relying on form-function relationships in other mammals and nonmammalian vertebrates. According to Cartmill, many of the key features of primates evolved for preying on insects in this special manner (Cartmill 1974).

Angiosperm-Primate Coevolution Hypothesis

The visual predation hypothesis was unpopular with some anthropologists. One reason for this is that many primates today are not especially predatory. Another is that, whereas primates do seem well adapted to moving around in the smallest, terminal branches of trees, insects are not necessarily easier to find there. A counterargument to the visual predation hypothesis is the angiosperm-primate coevolution hypothesis. Primate ecologist Robert Sussman (Sussman 1991) argued that the few primates that eat mostly insects often catch their prey on the ground rather than in tree branches. Furthermore, predatory primates often use their ears more than their eyes to detect prey. Finally, most early primate fossils show signs of having been omnivorous rather than insectivorous. Instead, he argued, the earliest primates were probably seeking fruit. Fruit (and flowers) of angiosperms (flowering plants) often develop in the terminal branches. Therefore, any mammal trying to access those fruits must possess anatomical traits that allow them to maintain their hold on thin branches and avoid falling while reaching for the fruits. Primates likely evolved their distinctive visual traits and extremities in the Paleocene (approximately 65 million to 54 million years ago) and Eocene (approximately 54 million to 34 million years ago) epochs, just when angiosperms were going through a revolution of their own—the evolution of large, fleshy fruit that would have been attractive to a small arboreal mammal. Sussman argued that, just as primates were evolving anatomical traits that made them more efficient fruit foragers, angiosperms were also evolving fruit that would be more attractive to primates to promote better seed dispersal. This mutually beneficial relationship between the angiosperms and the primates was termed coevolution or more specifically diffuse coevolution.

At about the same time, D. Tab Rasmussen noted several parallel traits in primates and the South American woolly opossum, Caluromys. He argued that early primates were probably foraging on both fruits and insects (Rasmussen 1990). As is true of Caluromys today, early primates probably foraged for fruits in the terminal branches of angiosperms, and they probably used their visual sense to aid in catching insects. Insects are also attracted to fruit (and flowers), so these insects represent a convenient opportunity for a primarily fruit-eating primate to gather protein. This solution is a compromise between the visual predation hypothesis and the angiosperm-primate coevolution hypothesis. It is worth noting that other models of primate origins have been proposed, and these include the possibility that no single ecological scenario can account for the origin of primates.

The Origins of Primates

Paleocene: Mammals in the Wake of Dinosaur Extinctions

Placental mammals, including primates, originated in the Mesozoic Era (approximately 251 million to 65.5 million years ago), the Age of Dinosaurs. During this time, most placental mammals were small, probably nocturnal, and probably avoided predators via camouflage and slow, quiet movement. It has been suggested that the success and diversity of the dinosaurs constituted a kind of ecological barrier to Mesozoic mammals. The extinction of the dinosaurs (and many other organisms) at the end of the Cretaceous Period (approximately 145.5–65.5 million years ago) might have opened up these ecological niches, leading to the increased diversity and disparity in mammals of the Tertiary Period (approximately 65.5–2.5 million years ago).

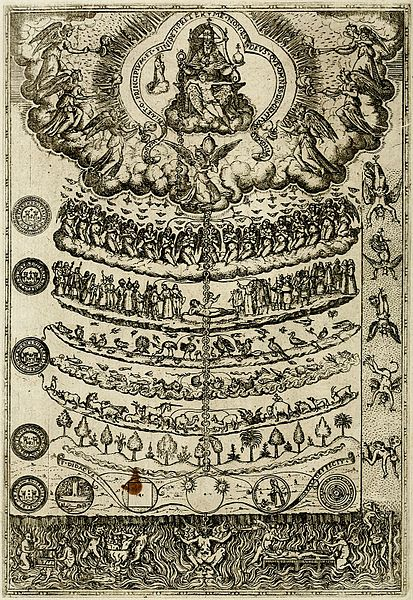

The Paleocene was the first epoch in the Age of Mammals. Soon after the Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) extinction event, new groups of placental mammals appear in the fossil record. Many of these groups achieved a broad range of sizes and lifestyles as well as a great number of species before declining sometime in the Eocene (or soon thereafter). These groups were ultimately replaced by the modern orders of placental mammals (Figure 8.3). It is unknown whether these replacements occurred gradually, for example by competitive exclusion, or rapidly, perhaps by sudden geographic dispersals with replacement. In some senses, the Paleocene might have been a time of recovery from the extinction event; it was cooler and more seasonal globally than the subsequent Eocene.

Plesiadapiforms, the Archaic Primates

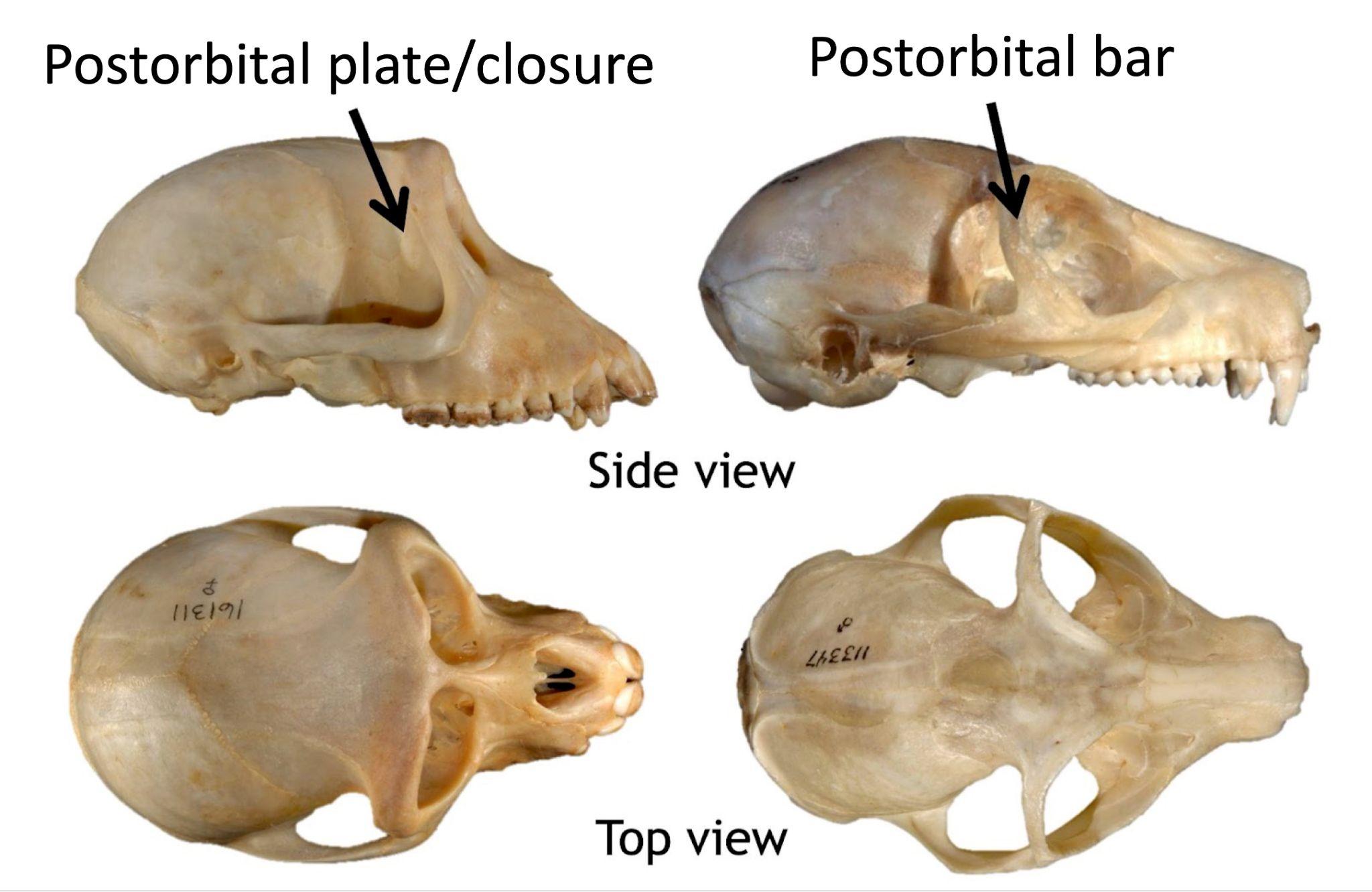

The Paleocene epoch saw the emergence of several families of mammals that have been implicated in the origin of primates. These are the plesiadapiforms, which are archaic primates, meaning they possessed some primate features and lacked others. The word plesiadapiform means “almost adapiform,” a reference to some similarities between some plesiadapiforms and some adapiforms (or adapoids; later-appearing true primates)—mainly in the molar teeth. Because enamel fossilizes better than other parts of the body, the molar teeth are the parts most often found and first discovered for any new species. Thus, dental similarities were often the first to be noticed by early mammalian paleontologists, partly explaining why plesiadapiforms were thought to be primates. Major morphological differences between plesidapiforms and euprimates (true primates) were observed later when more parts of plesiadapiform skeletons were discovered. Many plesiadapiforms have unusual anterior teeth and most have digits possessing claws rather than nails. So far, no plesiadapiform ever discovered has a postorbital bar (seen in extant strepsirrhines) or septum (as seen in haplorhines), and whether or not the auditory bulla was formed by the petrosal bone remains unclear for many plesiadapiform specimens. Nevertheless, there are compelling reasons (partly from new skeletal material) for including plesiadapiforms within the Order Primates.

Geographic and Temporal Distribution

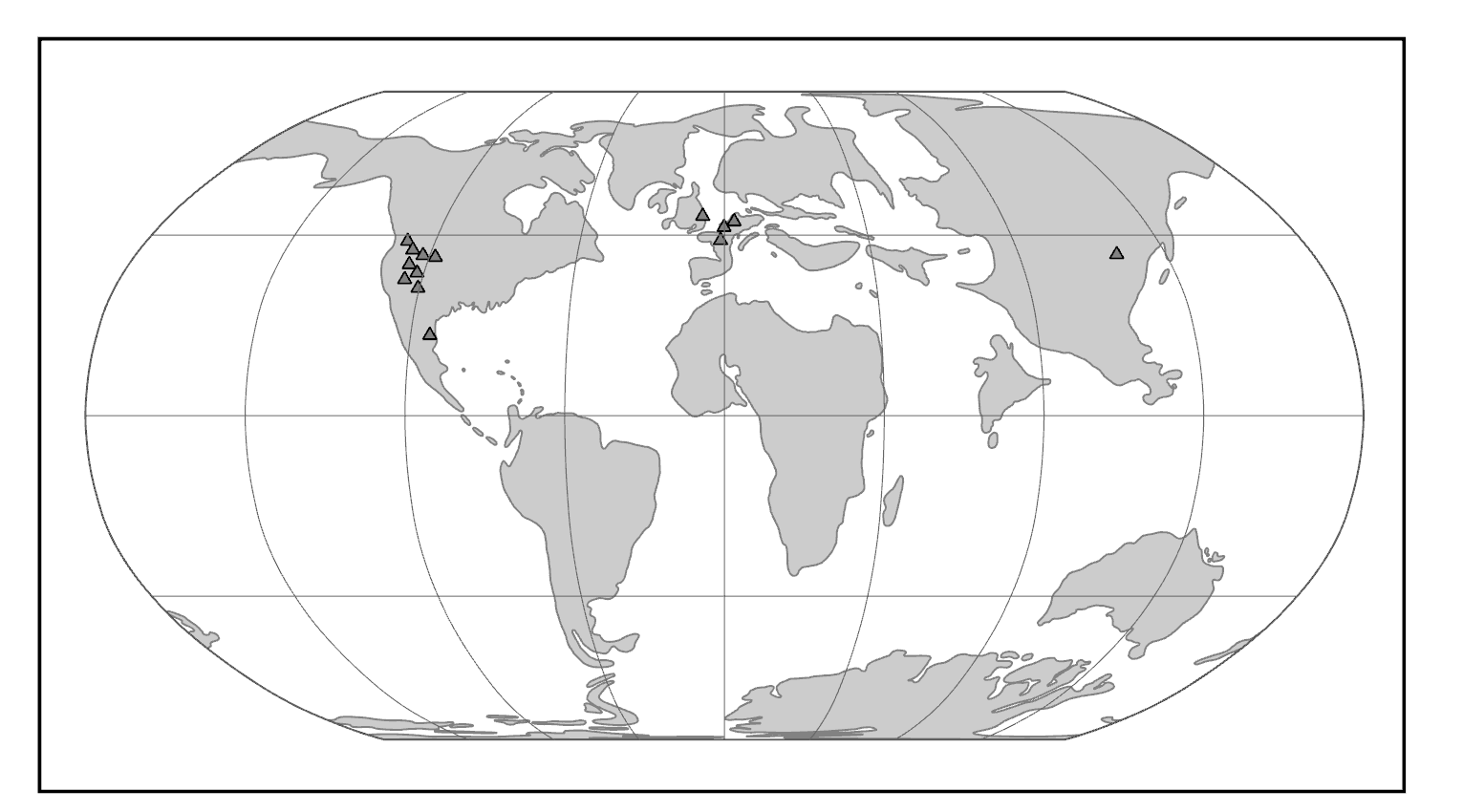

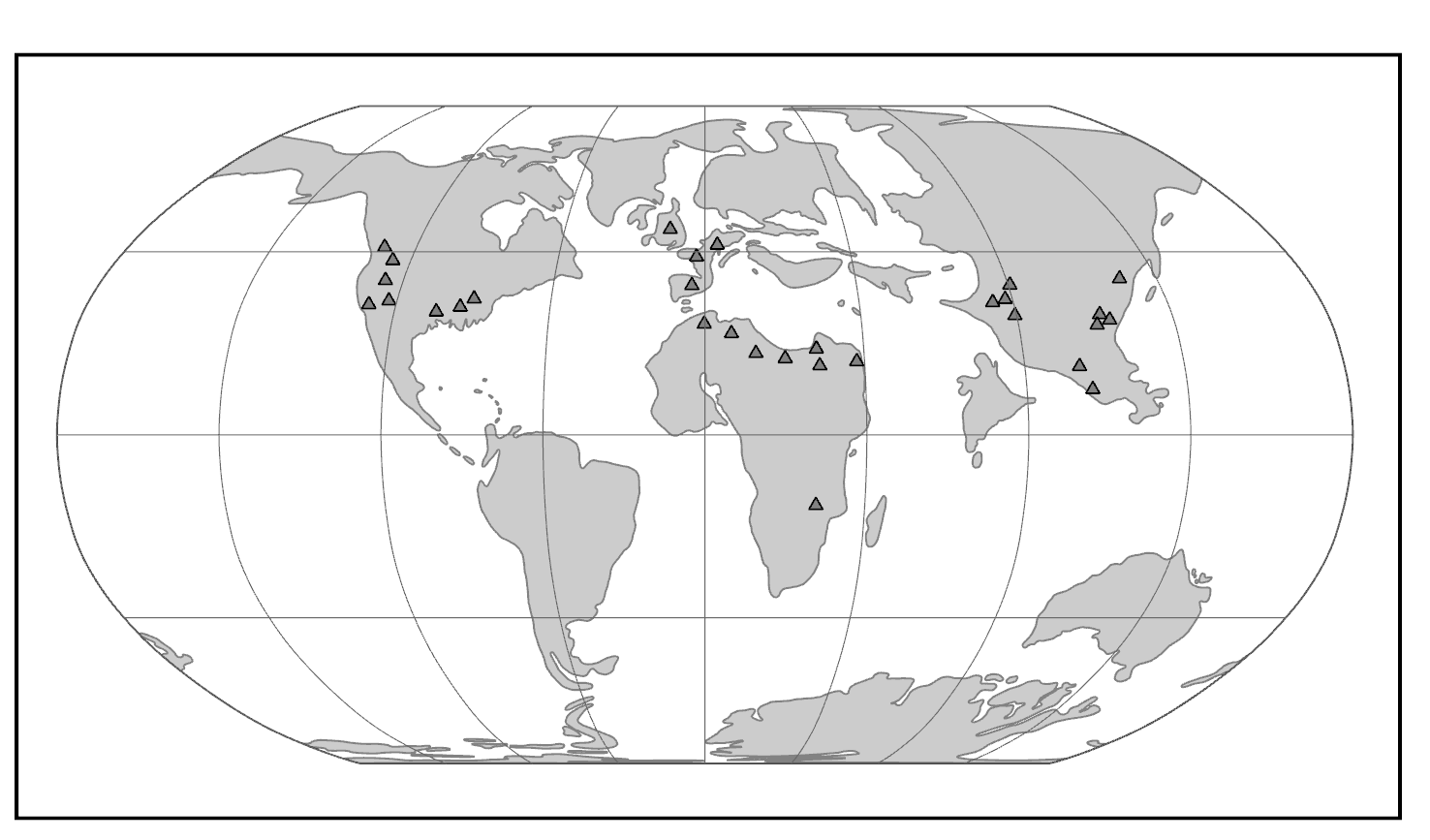

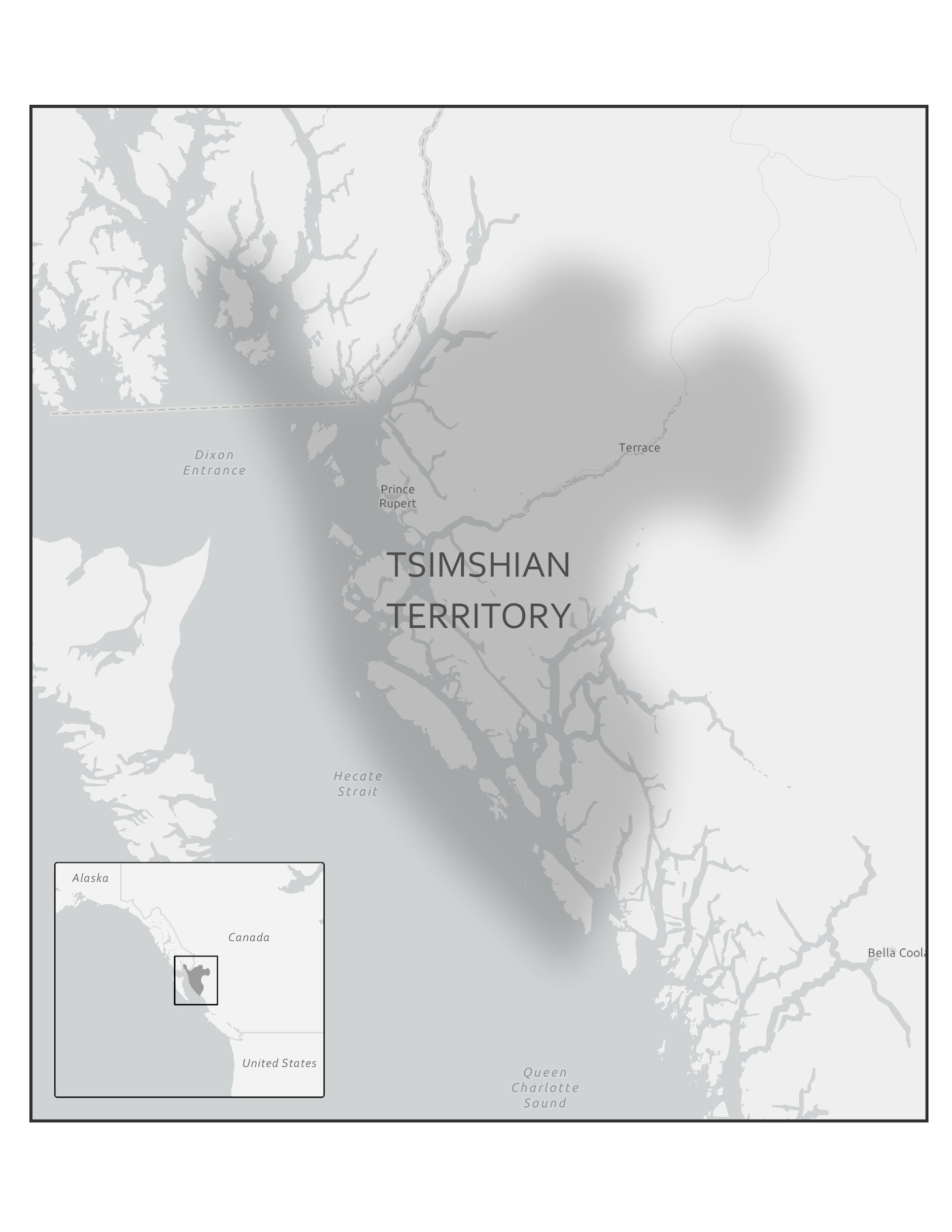

Purgatorius is generally considered to be the earliest primate. This Paleocene mammal is known from teeth that are very plesiomorphic for a primate. It has some characteristics that suggest it is a basal plesiadapiform, but there is very little to link it specifically with euprimates (see Clemens 2004). Its ankle bones suggest a high degree of mobility, signaling an arboreal lifestyle (Chester et al. 2015). Purgatorius is plesiomorphic enough to have given rise to all primates, including the plesiadapiforms. However, new finds suggest that this genus was more diverse and had more differing tooth morphologies than previously appreciated (Wilson Mantilla et al. 2021). Plesiadapiform families were numerous and diverse during parts of the Paleocene in western North America and western Europe, with some genera (e.g., Plesiadapis; see Figure 8.4) living on both continents (Figure 8.5). Thus, there were probably corridors for plesiadapiform dispersal between the two continents, and it stands to reason that these mammals were living all across North America, including in the eastern half of the continent and at high latitudes. A few plesiadapiforms have been described from Asia (e.g., Carpocristes), but the affinities of these remain uncertain.

|

Family

|

Genera

|

Morphology

|

Location

|

Age1

|

|

Paromomyidae |

Ignacius |

Long, dagger-like, lower incisor. |

North America and Europe |

Early Paleocene to Late Eocene |

|

Carpolestidae |

Carpolestes |

Plagiaulacoid dentition. Limb adaptations to terminal branch feeding. Grasping big toe. |

North America, Europe, and Asia |

Middle Paleocene to Early Eocene |

|

Plesiadapidae |

Plesiadapis |

Mitten-like upper incisor. Diastema. Large body size for group. |

North America and Europe |

Middle Paleocene to Early Eocene |

|

1 Derived from Fleagle 2013. |

|

|||

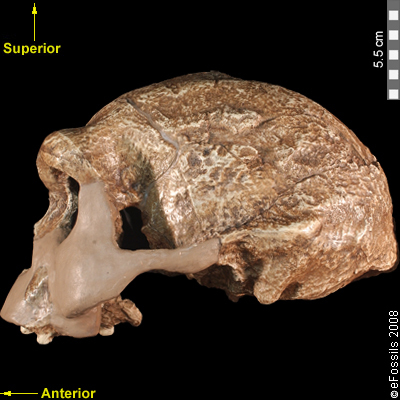

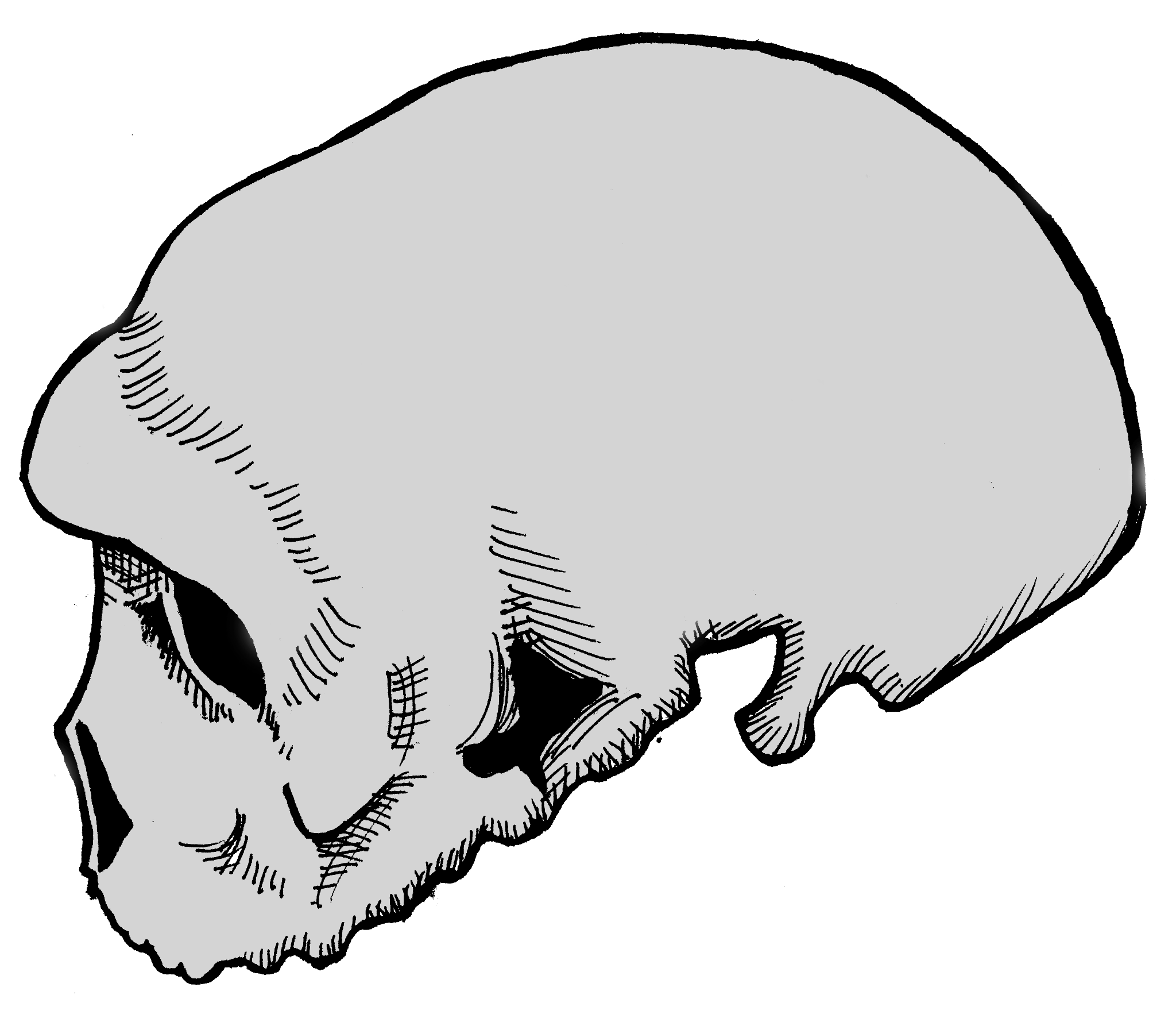

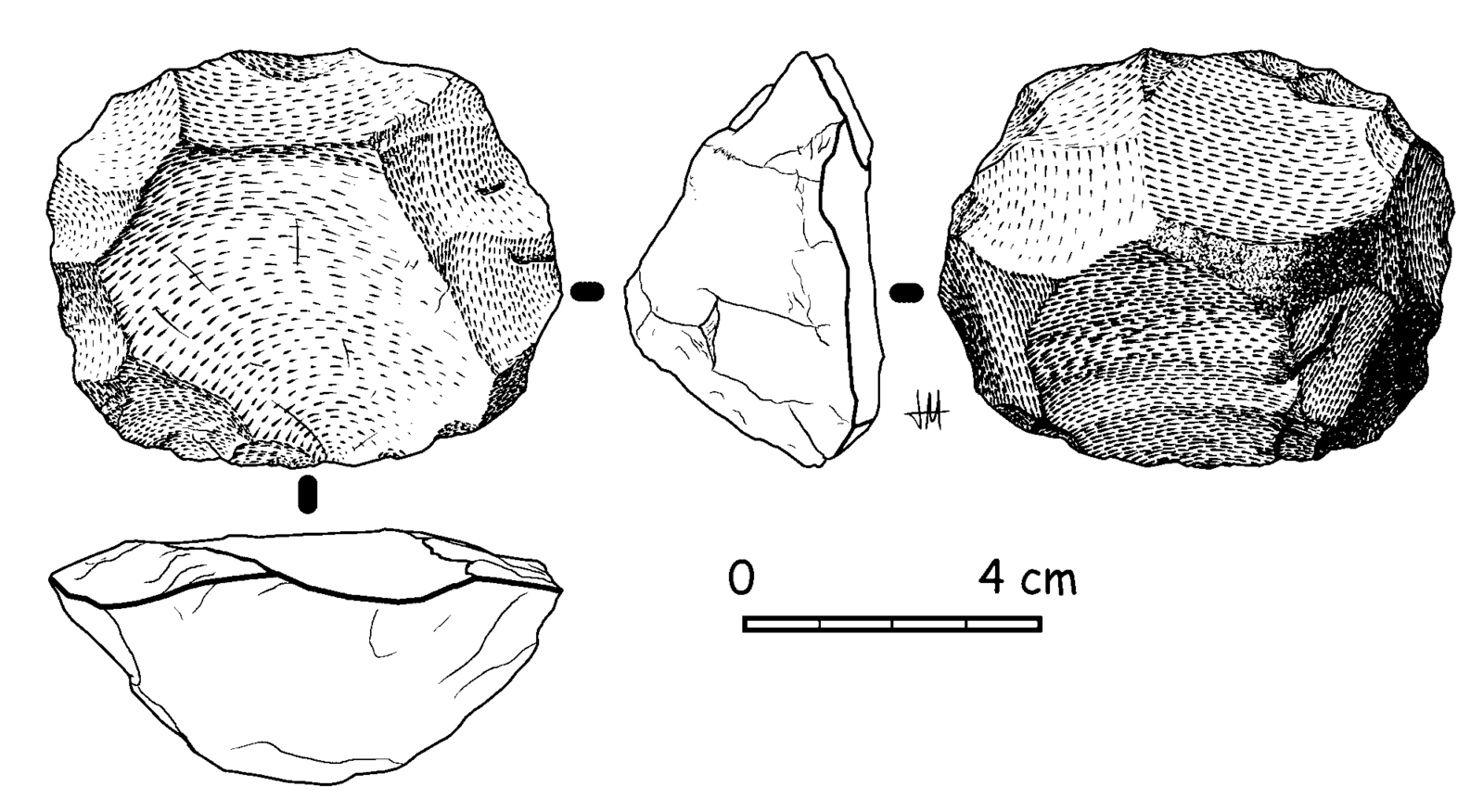

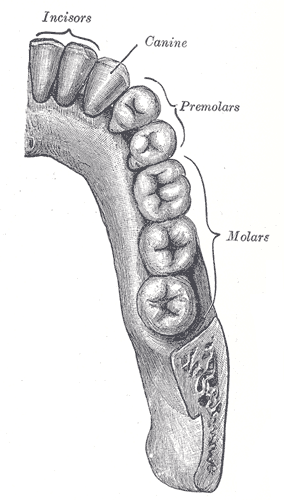

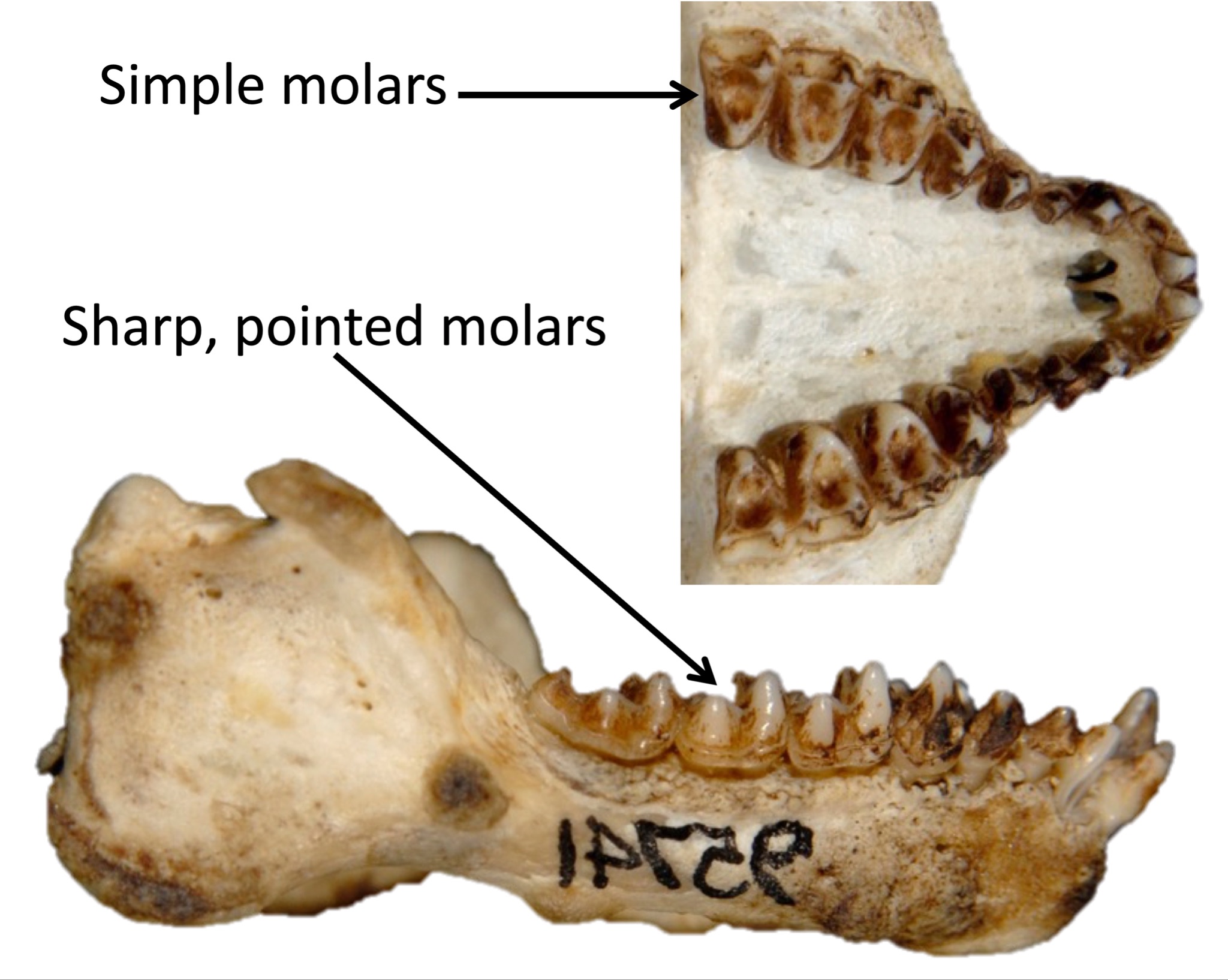

General Morphological Features

Although there is much morphological variation among the families of plesiadapiforms, some common features unite the group. Most plesiadapiforms were small, the largest being about three kilograms (approximately 7 lbs.; Plesiadapis cookei). They had small brains and fairly large snouts, with eyes that faced more laterally than in euprimates. Many species show reduction and/or loss of the canine and anterior premolars, with the resulting formation of a rodent-like diastema (a pronounced gap between the premolars and the incisors, with loss of at least the canine); this probably implies a herbivorous diet. Some families appear to have had very specialized diets, as suggested by unusual tooth and jaw shapes.

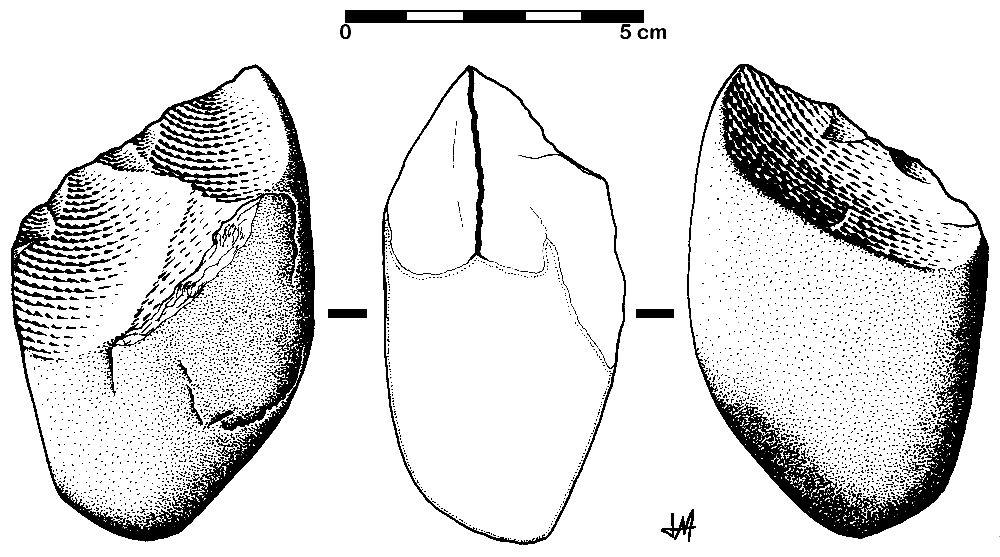

Arguably the most interesting and unusual family of plesiadapiforms is the Carpolestidae. They are almost exclusively from North America (with a couple of possible members from Asia), and mainly from the Middle and Late Paleocene. Their molars are not very remarkable, being quite similar to those of some other plesiadapiforms (e.g., Plesiadapidae). However, their lower posterior premolars (p4) are laterally compressed and blade-like with vertical serrations topped by tiny cuspules. This unusual dental morphology is termed plagiaulacoid (Simpson 1933). The upper premolar occlusal surfaces are broad and are covered with many small cuspules; the blade-like lower premolar might have cut across these cuspules, between them, or both.

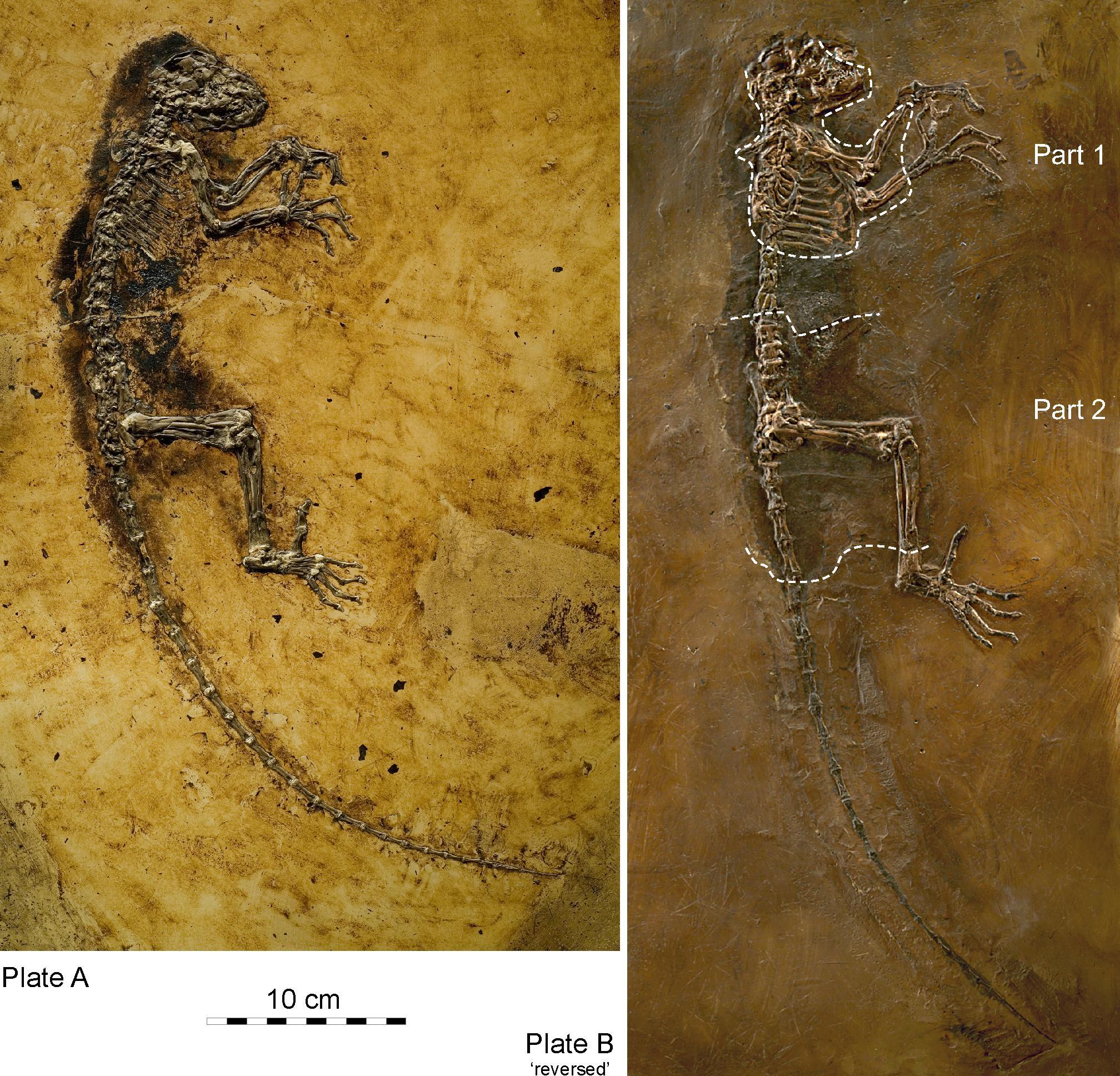

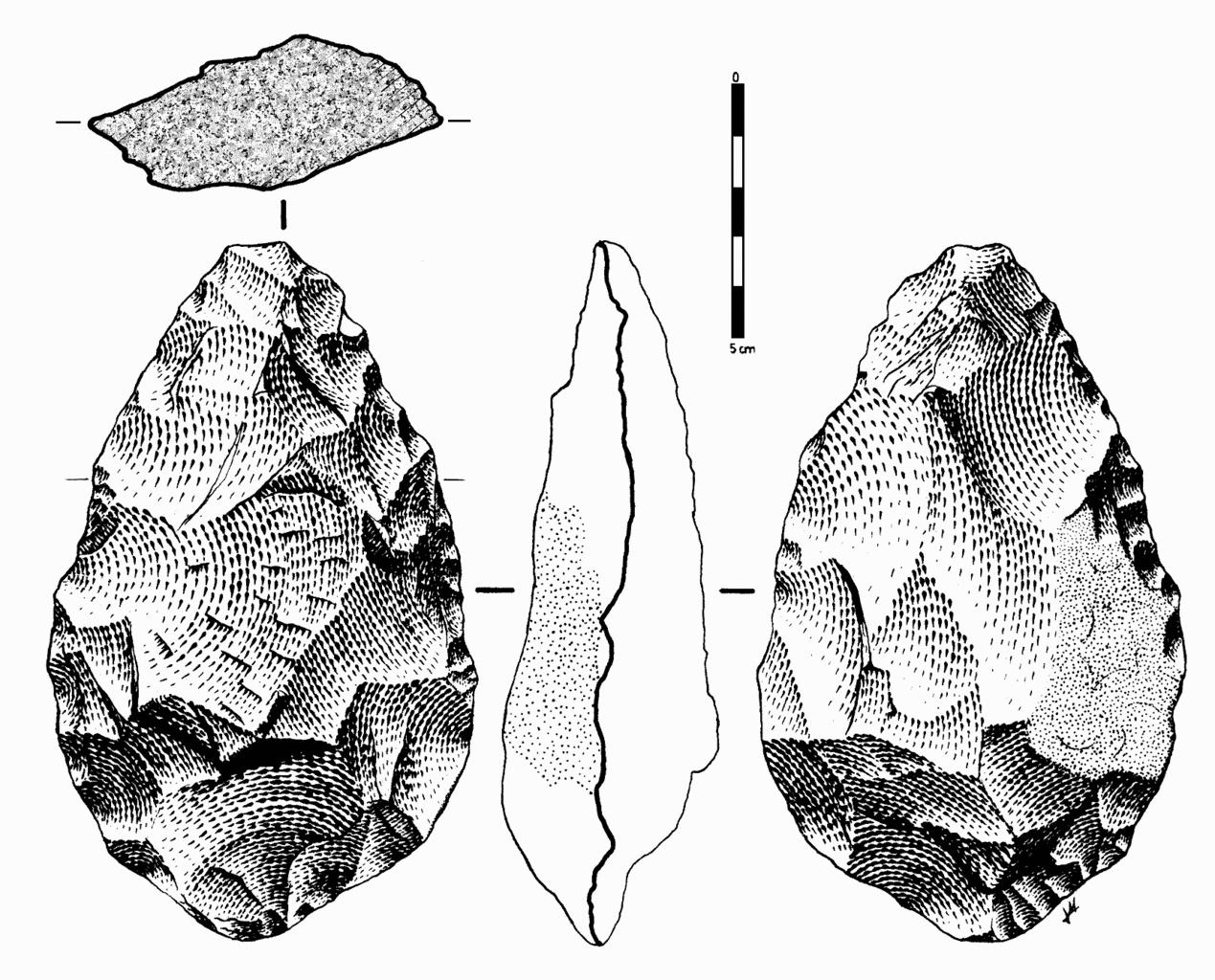

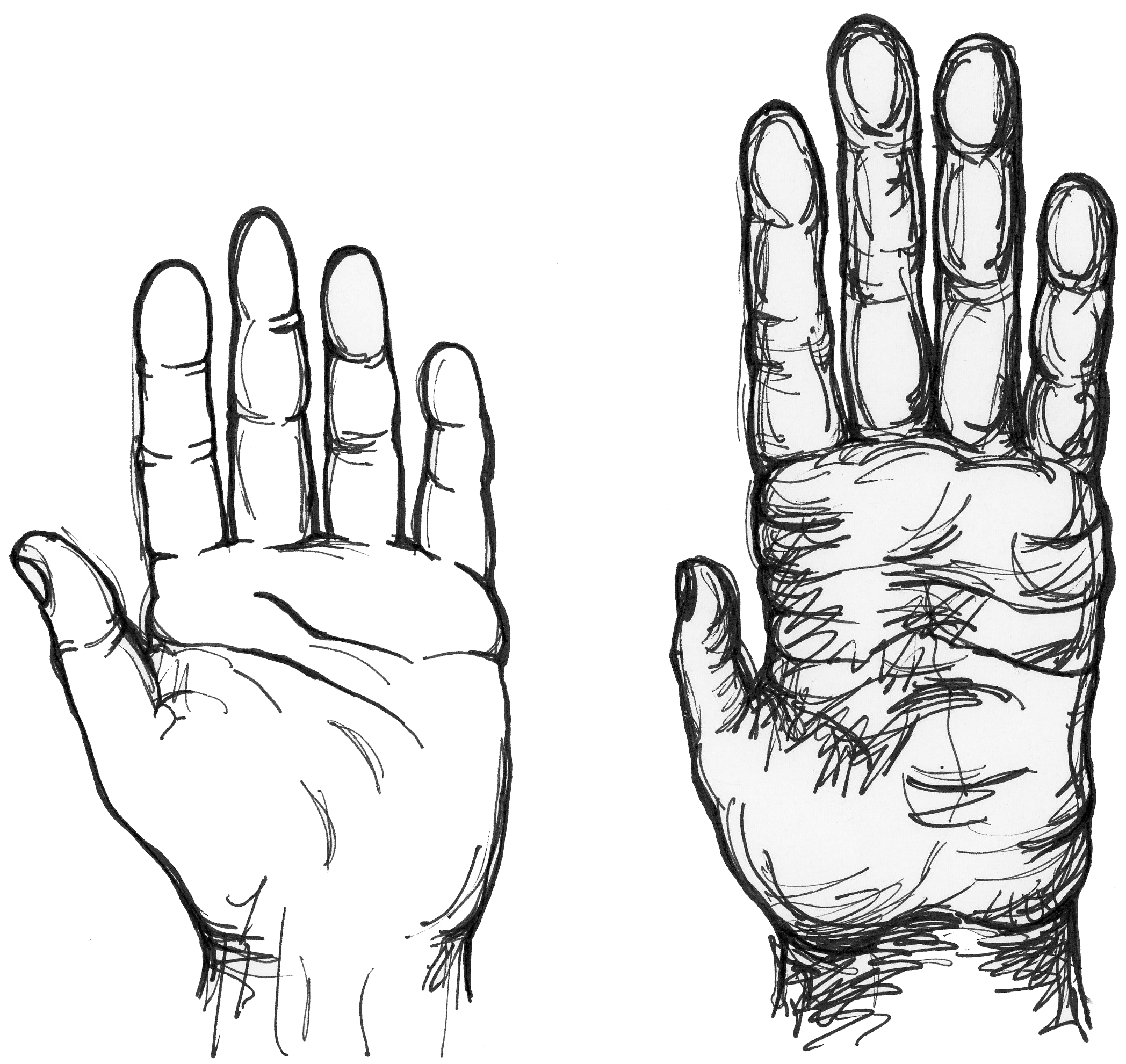

Many plesiadapiforms have robust limb bones with hallmarks of arboreality. Instead of having nails, most taxa had sharp claws on most or all of the digits. The extremities show grasping abilities comparable to those of primates and some arboreal marsupials. Nearly complete skeletons have yielded a tremendous wealth of information on locomotor and foraging habits. Many plesiadapiforms appear to have been able to cling to vertical substrates (like a broad tree trunk) using their sharp claws, propelling themselves upward using powerful hindlimbs, bounding along horizontal supports, grasping smaller branches, and moving head-first down tree trunks. In carpolestids in particular, the skeleton appears to have been especially well adapted to moving slowly and carefully in small terminal branches (Figure 8.6).

Debate: Relationship of Plesiadapiforms to True Primates (Transform to dig deeper /special topic)

In the middle of the twentieth century, treeshrews (Order Scandentia) were often considered part of the Order Primates, based on anatomical similarities between some treeshrews and primates. For many people, plesiadapiforms represented intermediates between primates and treeshrews, so plesiadapiforms were included in Primates as well.

Studies of reproduction and brain anatomy in treeshrews and lemurs suggested that treeshrews are not primates (e.g., Martin 1968). This was soon followed by the suggestion to also expel plesiadapiforms (Martin 1972) from the Order Primates. Like treeshrews, plesiadapiforms lack a postorbital bar, nails, and details of the ear region that characterize true primates. Many paleoanthropologists were reluctant to accept this move to banish plesiadapiforms (e.g., F. S. Szalay, P. D. Gingerich).

Later, K. Christopher Beard (1990) found that in some ways, the digits of paromomyid plesiadapiforms are actually more similar to those of dermopterans (Order Dermoptera), the closest living relatives of primates, than they are to those of primates themselves (but see Krause 1991). At the same time, Richard Kay and colleagues (1990) found that cranial circulation patterns and auditory bulla morphology in the paromomyid, Ignacius (see Figure 8.4), are more like those of dermopterans than of primates.

For many anthropologists, this one-two punch effectively removed plesiadapiforms from the Order Primates. In the last two decades, the tide of opinion has turned again, with many researchers reinstating plesiadapiforms as members of the Order Primates. New and more complete specimens demonstrate that the postcranial skeletons of plesiadapiforms, including the hands and feet, were primate-like, not dermorpteran-like (Bloch and Boyer 2002, 2007). New fine-grained CT scans of relatively complete plesiadapiform skulls revealed that they share some key traits with primates to the exclusion of other placental mammals (Bloch and Silcox 2006). Most significant was the suggestion that Carpolestes simpsoni possessed an auditory bulla formed by the petrosal bone, like in all living primates.

The debate about the status of plesiadapiforms continues, owing to a persistent lack of key bones in some species and owing to genuine complexity of the anatomical traits involved. Maybe plesiadapiforms were the ancestral stock from which all primates arose, with some plesiadapiforms (e.g., carpolestids) nearer to the primate stem than others.

Adapoids and Omomyoids, the First True Primates

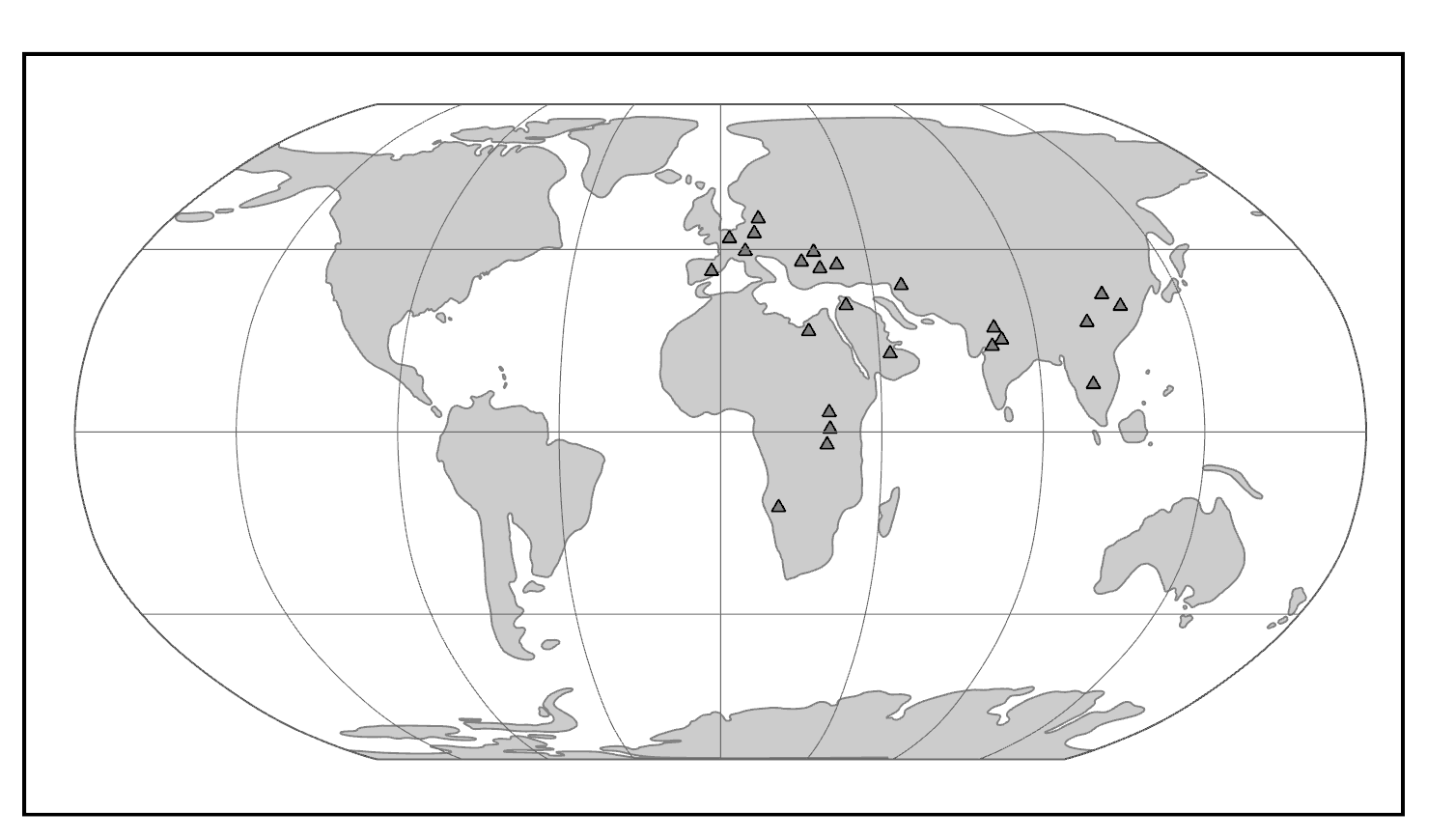

Geographic and Temporal Distribution

The first universally accepted fossil primates are the adapoids (Superfamily Adapoidea) and the omomyoids (Superfamily Omomyoidea). These groups become quite distinct over evolutionary time, filling mutually exclusive niches for the most part. However, the earliest adapoids are very similar to the earliest omomyoids.

The adapoids were mainly diurnal and herbivorous, with some achieving larger sizes than any plesiadapiforms (10 kg; 22 lbs.). By contrast, the omomyoids were mainly nocturnal, insectivorous and frugivorous, and small.

Both groups appear suddenly at the start of the Eocene, where they are present in western North America, western Europe, and India (Figure 8.7). This wide dispersal of early primates was probably due to the presence of rainforest corridors extending far into northern latitudes.

In North America and Europe, both groups achieved considerable diversity in the Middle Eocene, then mostly died out at the end of that epoch (Figure 8.8). In some Eocene rock formations in the western United States, adapoids and omomyoids make up a major part of the mammalian fauna. The Eocene of India has yielded a modest diversity of euprimates, some of which are so plesiomorphic that it is difficult to know whether they are adapoids or omomyoids (or even early anthropoids).

|

Family

|

Genera

|

Morphology

|

Location

|

Age1

|

|

Cercamoniidae |

Donrussellia |

Variable in tooth number and jaw shape. |

Europe and Asia |

Early to Late Eocene |

|

Asiadapidae2 |

Asiadapis |

Plesiomorphic teeth and jaw resemble early Omomyids. |

Asia |

Early Eocene |

|

Caenopithecidae3 |

Darwinius |

Robust jaws with crested molars. Fewer premolars. |

Europe, Africa, North America, and Asia |

Middle to Late Eocene |

|

Adapidae |

Adapis |

Fused mandible. Long molar crests. Large size and large chewing muscles. |

Europe |

Late Eocene to Early Oligocene |

|

Sivaladapidae |

Sivaladapis |

Some large with robust jaws. |

Asia |

Middle Eocene to Late Miocene |

|

Notharctidae4 |

Notharctus |

Canine sexual dimorphism. Lemur-like skull. Clinging and leaping adaptations. |

North America and Europe |

Early to Middle Eocene |

|

Omomyidae5 |

Teilhardina |

Small, nocturnal, frugivorous or insectivorous. Tarsier-like skull in some. |

North America, Europe, and Asia |

Early Eocene to Early Miocene |

|

Microchoeridae6 |

Necrolemur |

Long bony ear tubes. Tarsier-like lower limb adaptations for leaping. |

Europe and Asia |

Early Eocene to Early Oligocene |

|

1 Derived from Fleagle 2013. 2 See Dunn et al. 2016 and Rose et al. 2018. 3 See Kirk and Williams 2011 and Seiffert et al. 2009. 4 See Gregory 1920. 5 See Beard and MacPhee 1994 and Strait 2001. 6 See Schmid 1979. |

|

|||

Adapoids and omomyoids barely survived the Eocene-Oligocene extinctions, when colder temperatures, increased seasonality, and the retreat of rainforests to lower latitudes led to changes in mammalian biogeography. In North America, one genus (originally considered an omomyoid but recently reclassified as Adapoidea) persisted until the Miocene: Ekgmowechashala (Rose and Rensberger 1983). This taxon has highly unusual teeth and might have been a late immigrant to North America from Asia. In Asia, one family of adapoids, the Sivaladapidae, retained considerable diversity as late as the Late Miocene.

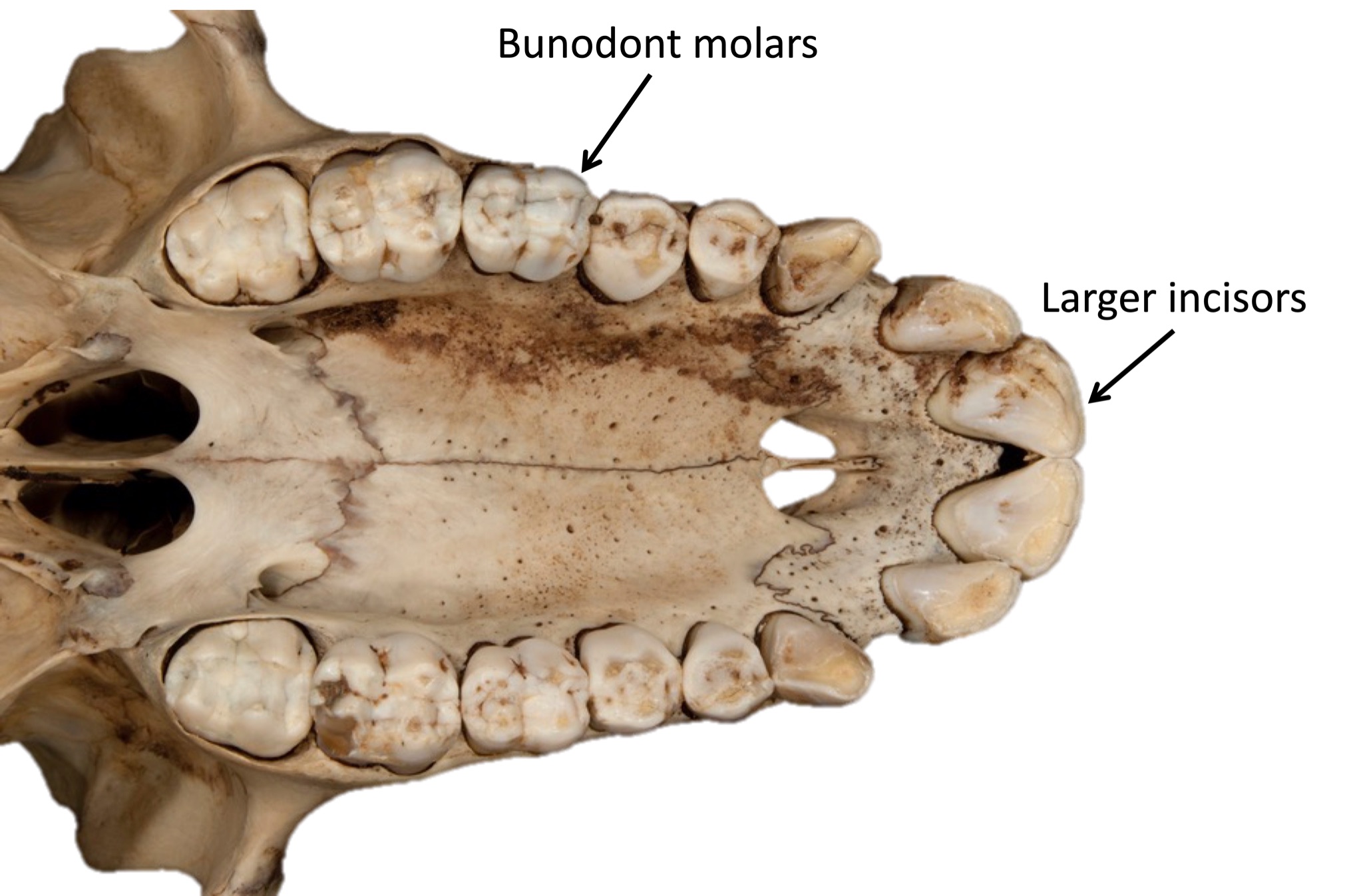

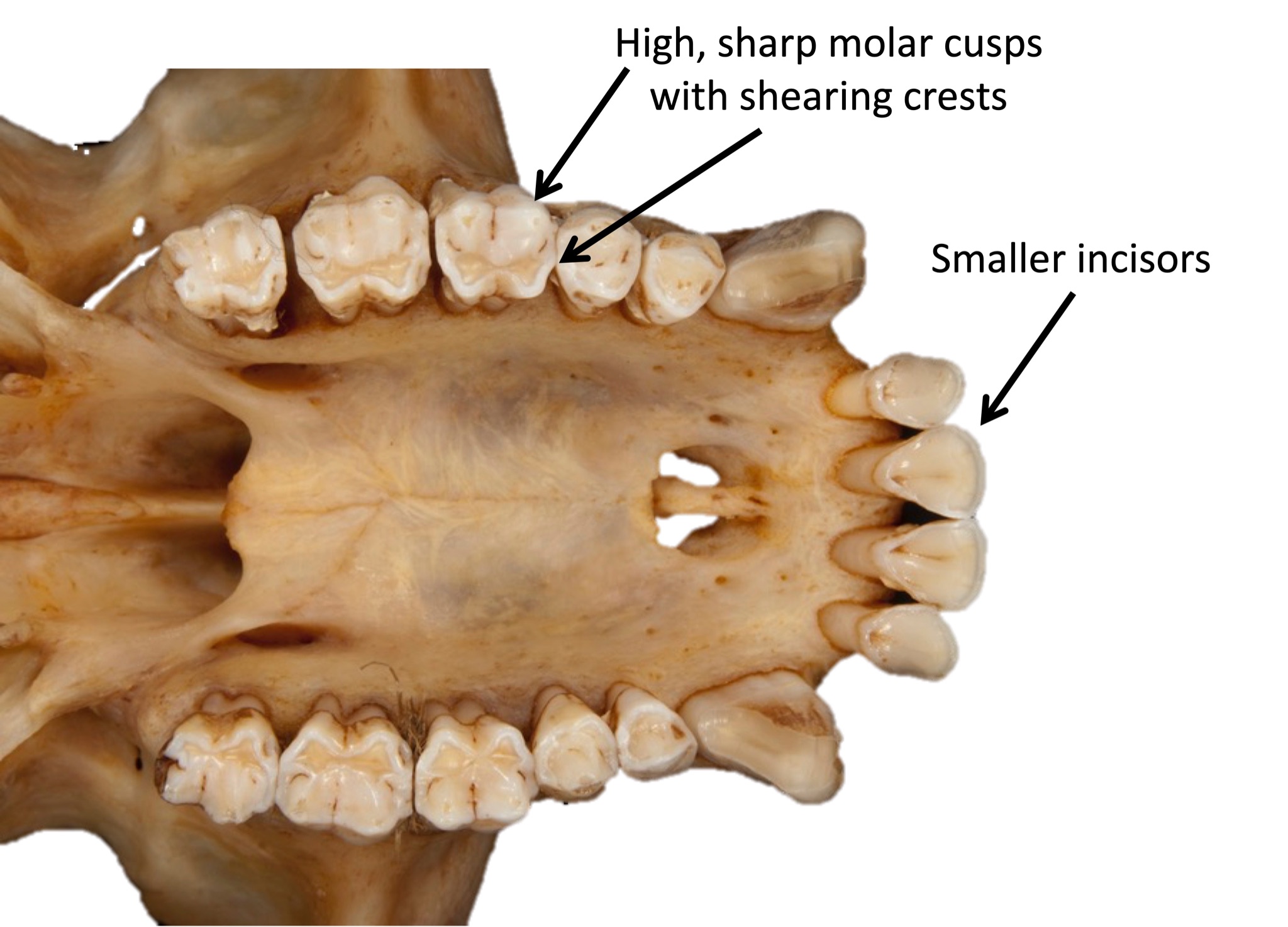

Adapoid Diversity

Adapoids were very diverse, particularly in the Eocene of North America and Europe. They can be divided into six families, with a few species of uncertain familial relationship. As a group, adapoids have some features in common, although much of what they share is plesiomorphic. Important features include the hallmarks of euprimates: postorbital bar, flattened nails, grasping extremities, and a petrosal bulla (Figures 8.9 and 8.10). In addition, some adapoids retain the ancestral dental formula of 2.1.4.3; that is, in each quadrant of the mouth, there are two incisors, one canine, four premolars, and three molars. In general, the incisors are small compared to the molars, but the canines are relatively large, with sexual dimorphism in some species. Cutting crests on the molars are well developed in some species, and the two halves of the mandible were fused at the midline in some species. Some adapoids were quite small (Anchomomys at a little over 100 g), and some were quite large (Magnadapis at 10 kg; 22 lbs.). Furthermore, the spaces and attachment features for the chewing muscles were truly enormous in some species, suggesting that these muscles were very large and powerful. Taken together, this suggests an overall adaptive profile of diurnal herbivory. The canine sexual dimorphism in some species suggests a possible mating pattern of polygyny, as males in polygynous primate species often compete with each other for mates and have especially large canine teeth.

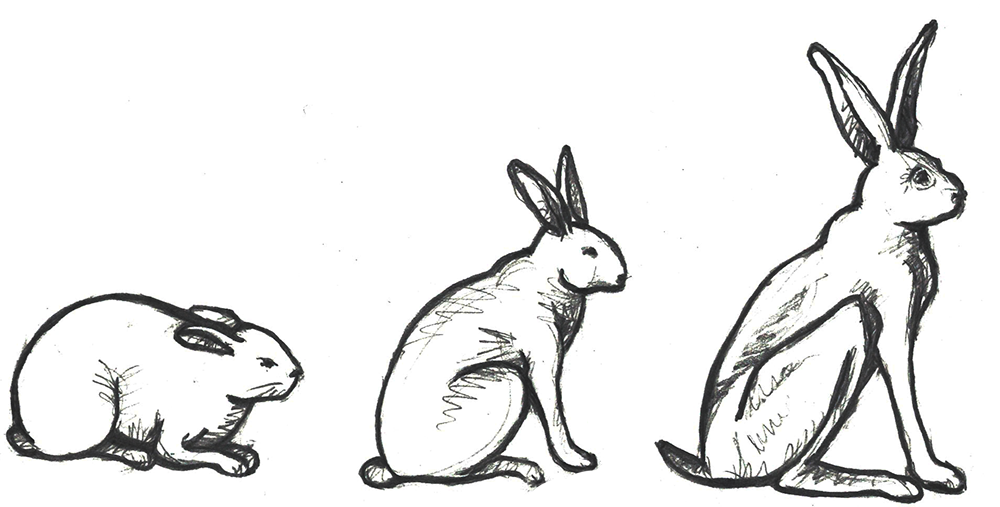

Omomyoid Diversity

Like adapoids, omomyoids appeared suddenly at the start of the Eocene and then became very diverse with most species dying out before the Oligocene. Omomyoids are known from thousands of jaws with teeth, relatively complete skulls for about a half-dozen species, and very little postcranial material. Omomyoids were relatively small primates, with the largest being less than three kilograms (approximately 7 lbs.; Macrotarsius montanus). All known crania possess a postorbital bar, which in some has been described as “incipient closure.” Some—but not all—known crania have an elongated bony ear tube extending lateral to the location of the eardrum, a feature seen in living tarsiers and catarrhines. The anterior teeth tend to be large, with canines that are usually not much larger than the incisors. Often it is difficult to distinguish closely related species using molar morphology, but the premolars tend to be distinct from one species to another. The postcranial skeleton of most omomyoids shows hallmarks of leaping behavior reminiscent of that of tarsiers. In North America, omomyoids became very diverse and abundant. In fact, omomyoids from Wyoming are sufficiently abundant and from such stratigraphically controlled conditions that they have served as strong evidence for the gradual evolution of anatomical traits over time (Rose and Bown 1984).

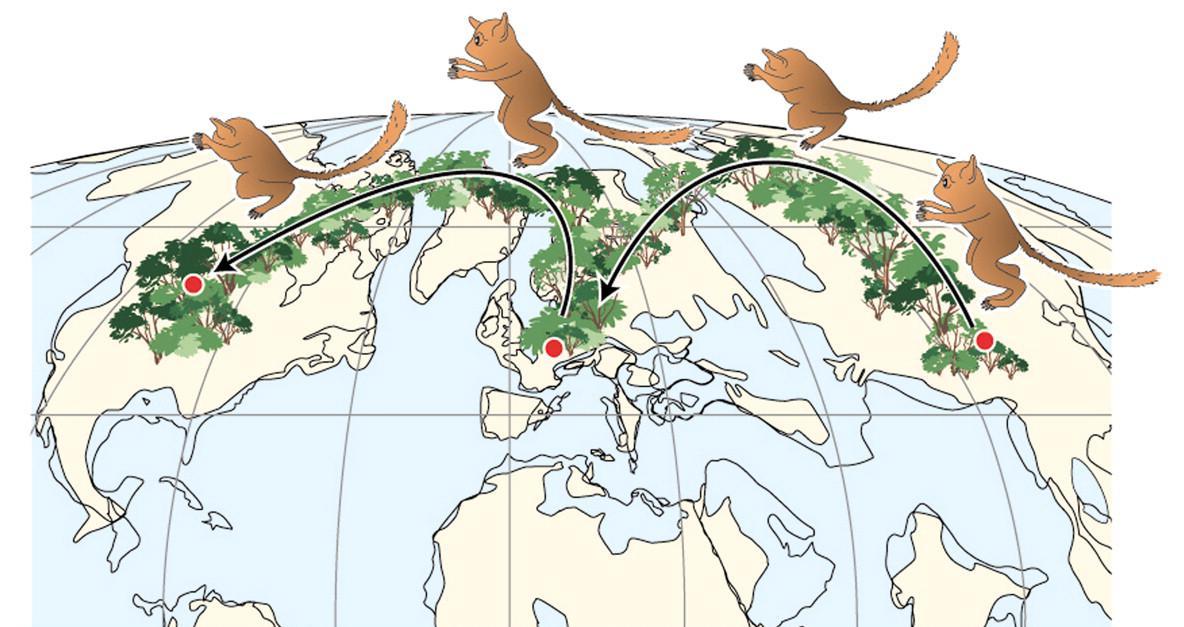

Teilhardina (Figure 8.11; see Figure 8.2) is one of the earliest and arguably the most plesiomorphic of omomyoids. Teilhardina has several species, most of which are from North America, with one from Europe (T. belgica) and one from Asia (T. asiatica). The species of this genus are anatomically similar and the deposits from which they are derived are roughly contemporaneous. Thus, this small primate likely dispersed across the northern continents very rapidly (Smith et al. 2006).

The Emergence of Modern Primate Groups

Origins of Crown Strepsirrhines

Until the turn of this century, very little was known about the origins of the crown (living) strepsirrhines. The Quaternary record of Madagascar contains many amazing forms of lemurs, including giant sloth-like lemurs, lemurs with perhaps monkey-like habits, lemurs with koala-like habits, and even a giant aye-aye (Godfrey and Jungers 2002). However, in Madagascar, early Tertiary continental sediments are lacking, and there is no record of lemur fossils before the Pleistocene.

The fossil record of galagos is slightly more informative. Namely, there are Miocene African fossils that are very likely progenitors of lorisids (Simpson 1967). However, these are much like modern galagos and do not reveal anything about the relationship between crown strepsirrhines and Eocene fossil primates (but see below regarding Propotto). A similar situation exists for lorises in Asia: there are Miocene representatives, but these are substantially like modern lorises. The discovery of the first definite toothcomb canine (a hallmark of stresirrhines) in 2003 provided the “smoking gun” for the origin of crown strepsirrhines (Seiffert et al. 2003). Recently, several other African primates have been recognized as having strepsirrhine affinities (Marivaux et al. 2013; Seiffert 2012). The enigmatic Fayum primate Plesiopithecus is known from a skull that has been compared to aye-ayes and to lorises (Godinot 2006; Simons and Rasmussen 1994a).

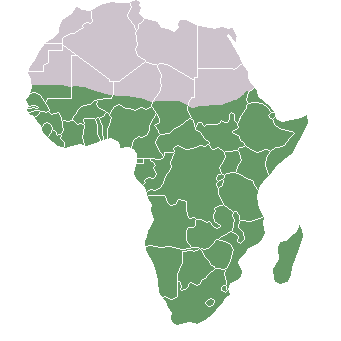

The now-recognized diversity of stem strepsirrhines from the Eocene and Oligocene of Afro-Arabia is strong evidence to suggest that strepsirrhines originated in that geographic area. This implies that lorises dispersed to Asia subsequent to an African origin. It is unknown what the first strepsirrhines in Madagascar were like. However, it seems likely that the lemuriform-lorisiform split occurred in continental Africa, followed by dispersal of lemuriform stock to Madagascar. Recent evidence suggests that Propotto, a Miocene primate from Kenya originally described as a potto antecedent, actually forms a clade with Plesiopithecus and the aye-aye; this might suggest that strepsirrhines dispersed to Madagascar from continental Africa more than once (Gunnell et al. 2018).

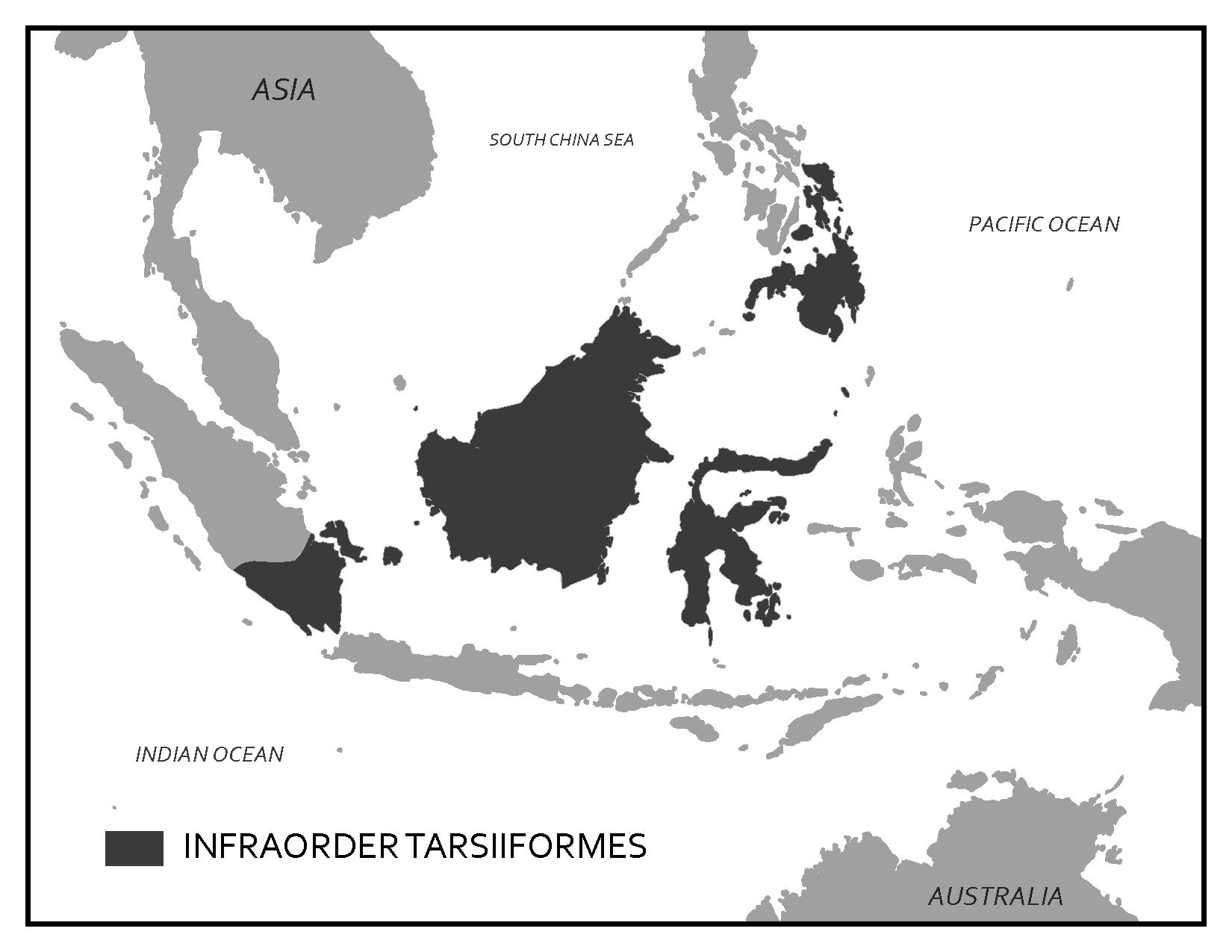

The Fossil Record of Tarsiers

Tarsiers are so unusual that they fuel major debates about primate taxonomy. Tarsiers today are moderately diverse but geographically limited and not very different in their ecological habits—especially considering that the split between them and their nearest living relative probably occurred over 50 million years ago. If omomyoids are excluded, then the fossil record of tarsiers is very limited. Two fossil species from the Miocene of Thailand have been placed in the genus Tarsius, as has an Eocene fossil from China (Beard et al. 1994). These, and Xanthorhysis from the Eocene of China, are all very tarsier-like. In fact, it is striking that Tarsius eocaenus from China was already so tarsier-like as early as the Eocene. This suggests that tarsiers achieved their current morphology very early in their evolution and have remained more or less the same while other primates changed dramatically. Two additional genera, Afrotarsius from the Oligocene of Egypt and Libya and Afrasia from the Eocene of Myanmar, have also been implicated in tarsier origins, though the relationship between them and tarsiers is unclear (Chaimanee et al. 2012). More recently, a partial skeleton of a small Eocene primate from China, Archicebus achilles (dated to approximately 55.8 million to 54.8 million years ago), was described as the most basal tarsiiform (Ni et al. 2013). This primate is reconstructed as a diurnal insectivore and an arboreal quadruped that did some leaping—but not to the specialized degree seen in living tarsiers. The anatomy of the eye in living tarsiers suggests that their lineage passed through a diurnal stage, so Archicebus (and diurnal omomyoids) might represent such a stage.

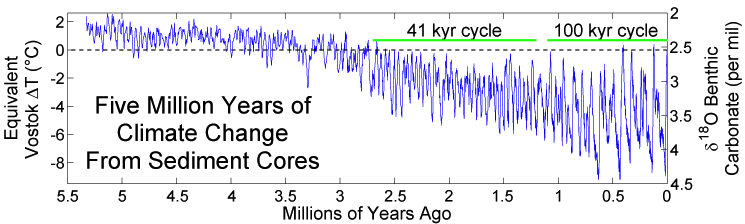

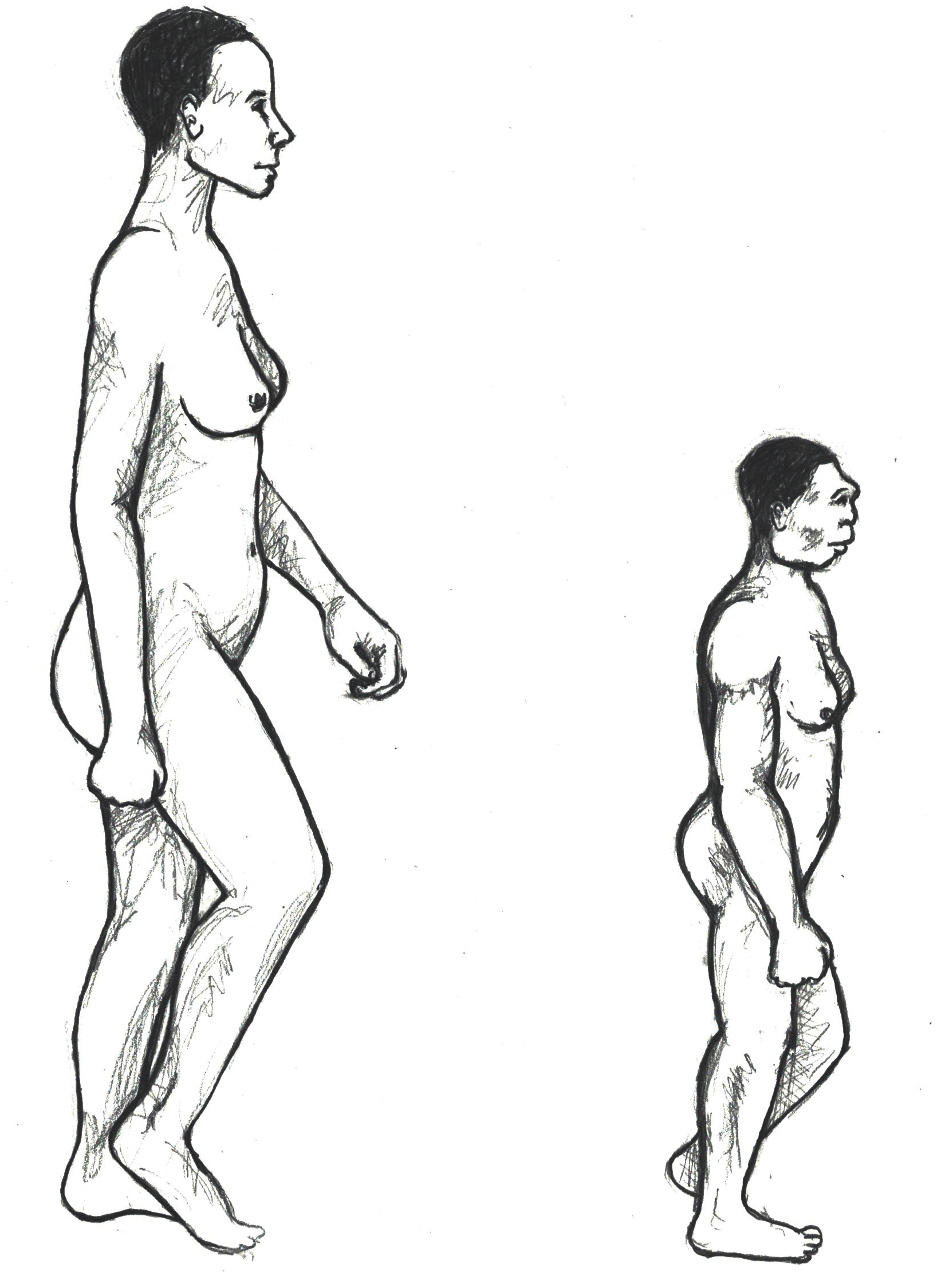

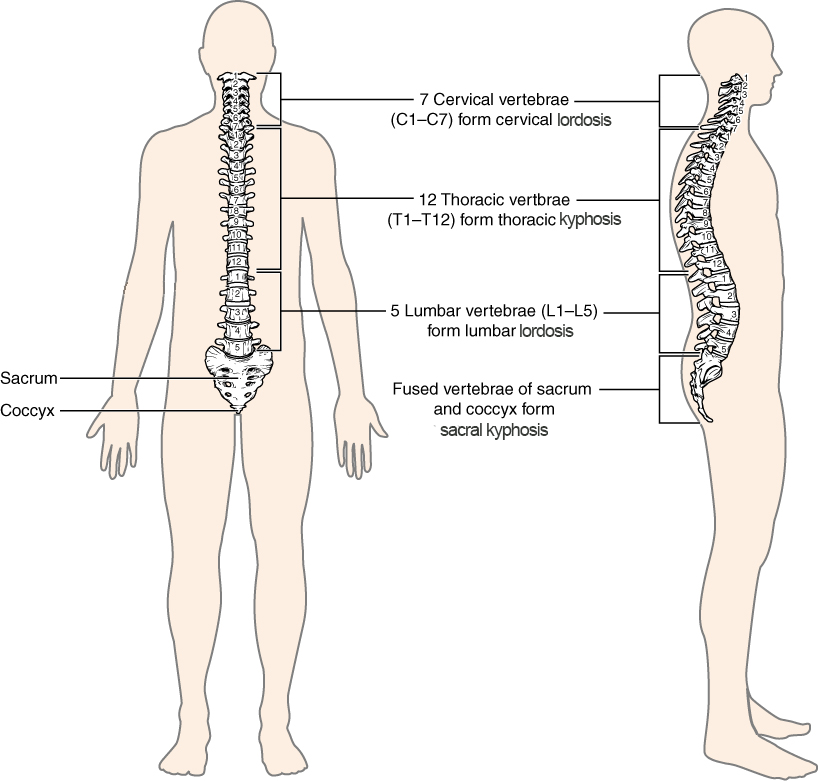

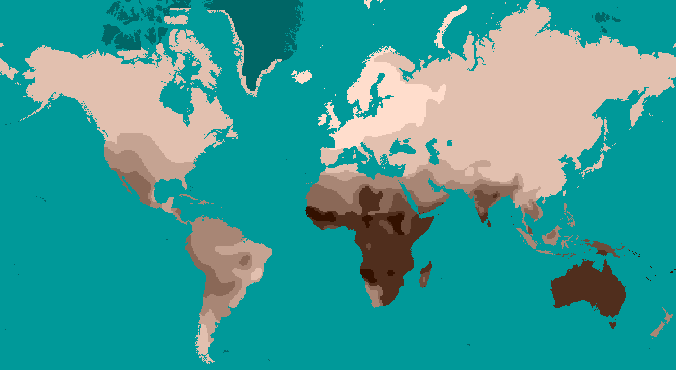

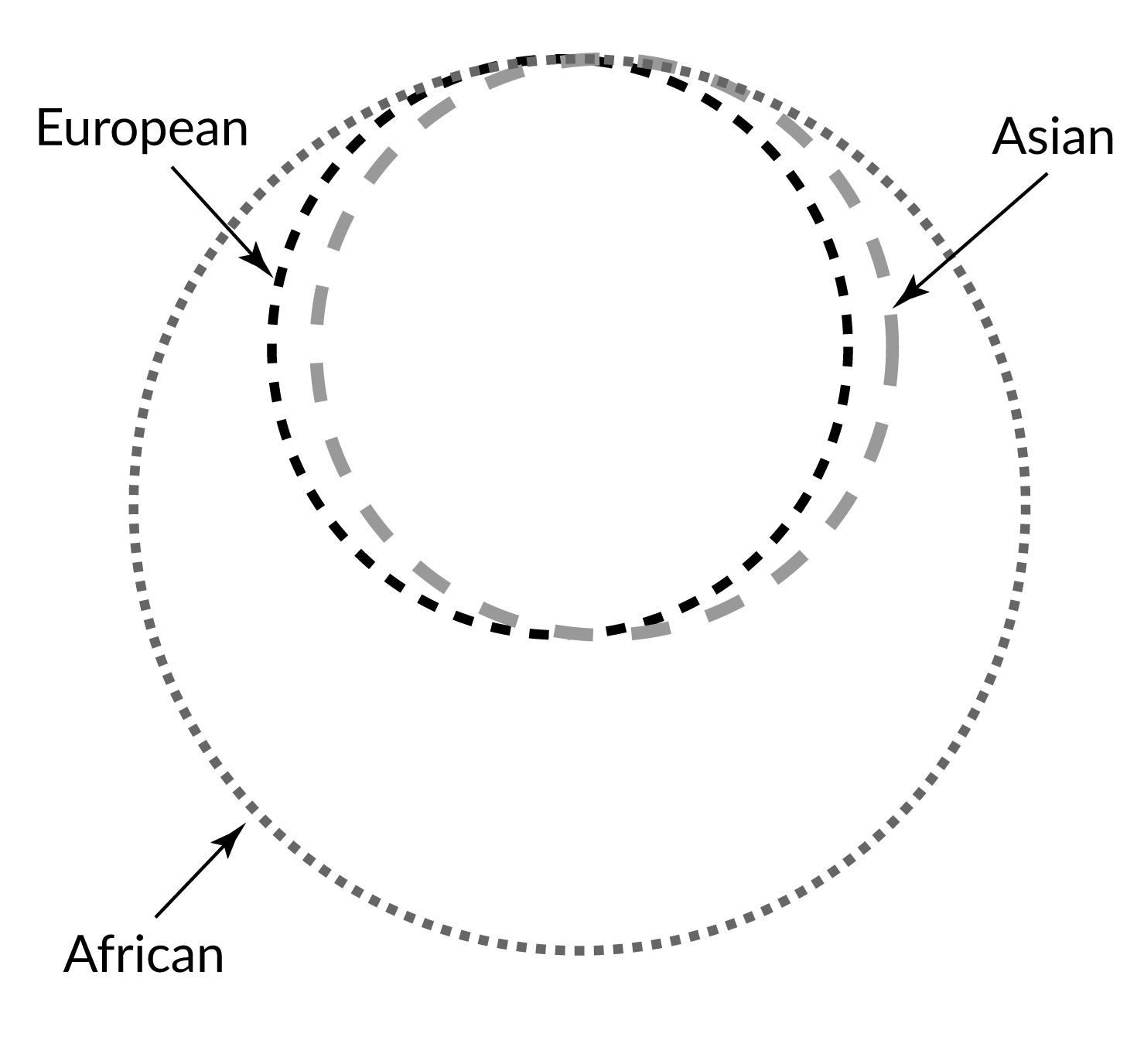

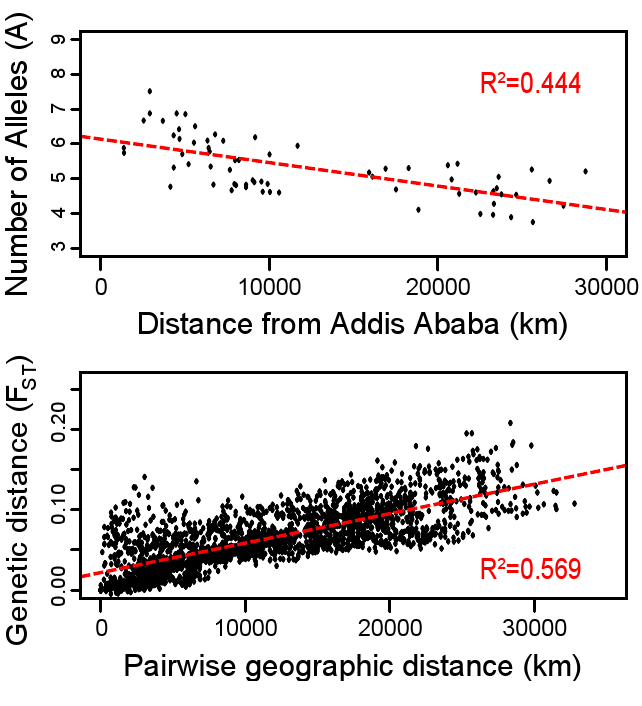

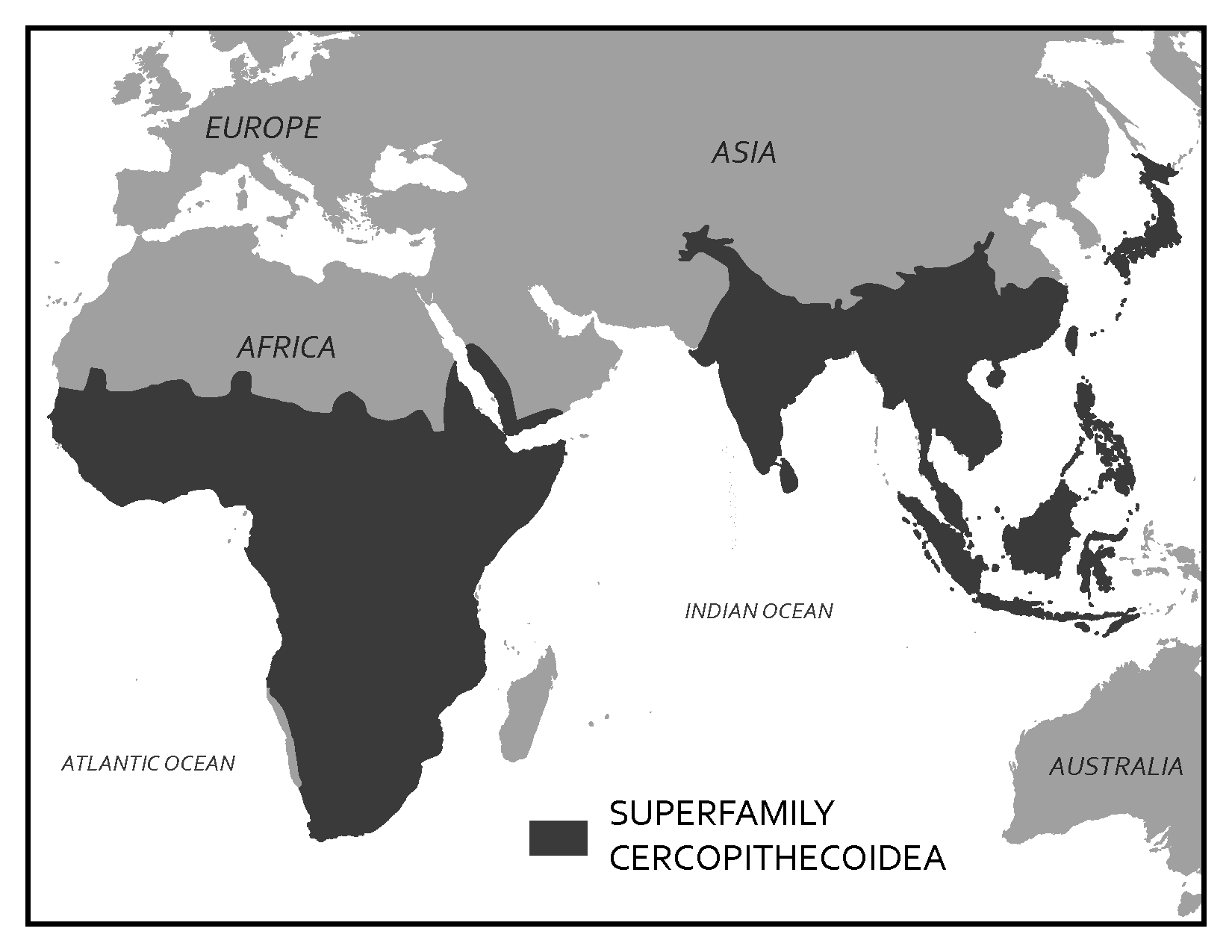

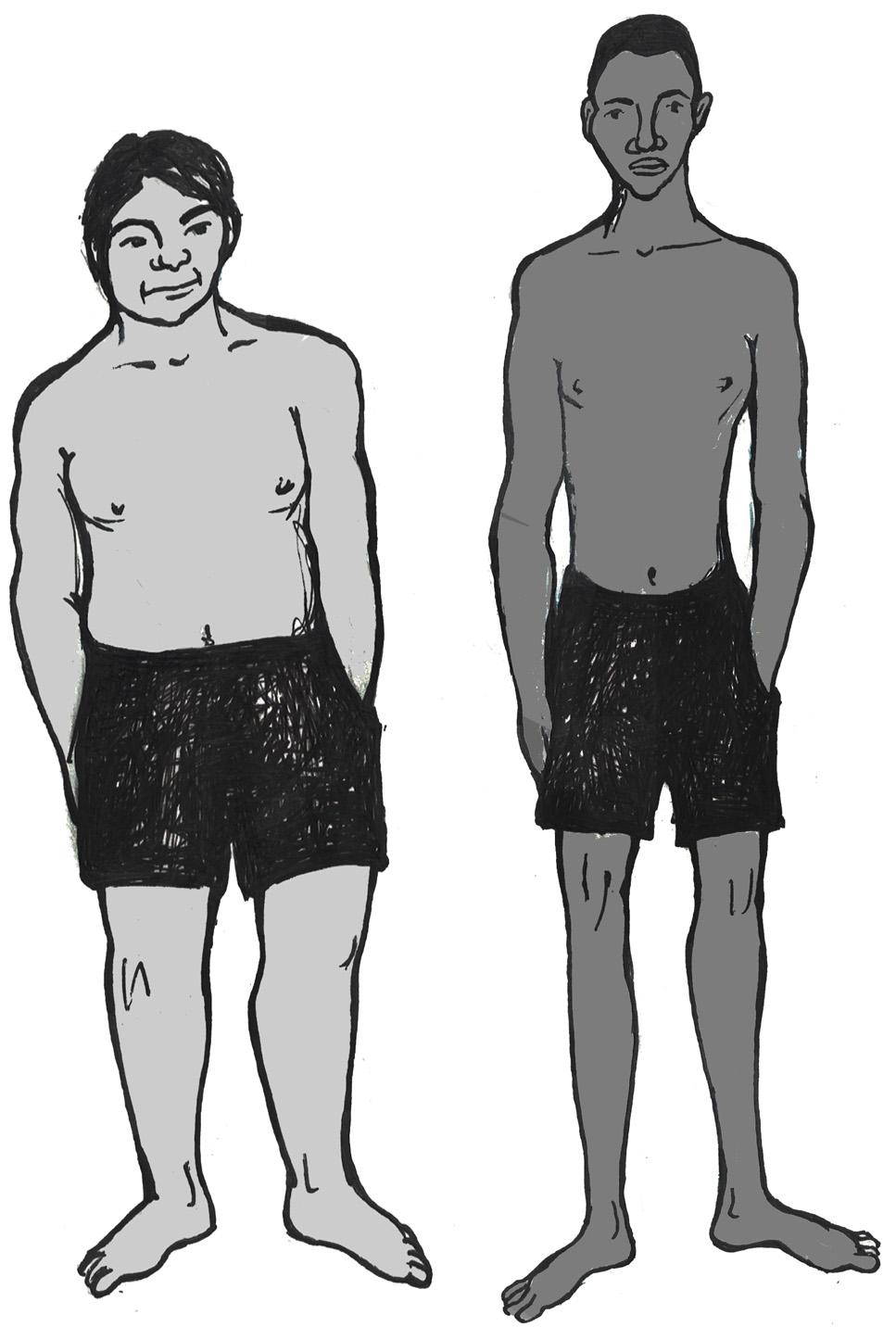

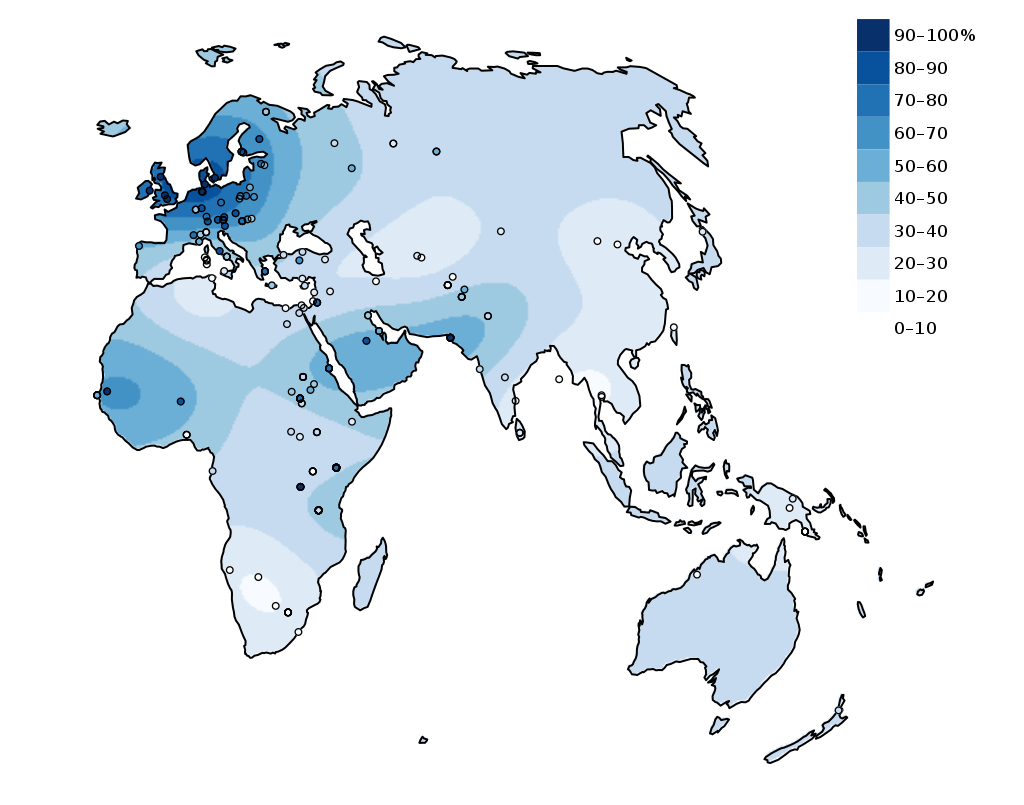

Climate Change and the Paleogeography of Modern Primate Origins

Changing global climate has had profound effects on primate dispersal patterns and ecological habits over evolutionary time. Primates today are strongly tied to patches of trees and particular plant parts such as fruits, seeds, and immature leaves. It is no surprise, then, that the distribution of primates mirrors the distribution of forests. Today, primates are most diverse in the tropics, especially in tropical rainforests. Global temperature trends across the Tertiary have affected primate ranges. Following the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event, cooler temperatures and greater seasonality characterized the Paleocene. In the Eocene, temperatures (and probably rainfall) increased globally and rainforests likely extended to very high latitudes. During this time, euprimates became diverse. With cooling and increased aridity at the end of the Eocene, many primate extinctions occurred in the northern continents and the surviving primates were confined to lower latitudes in South America, Afro-Arabia, Asia, and southern Europe. Among these survivors are the progenitors of the living groups of primates: lemurs and lorises, tarsiers, platyrrhines (monkeys of the Americas), and catarrhines (monkeys and apes of Africa and Asia) (Figure 8.12).

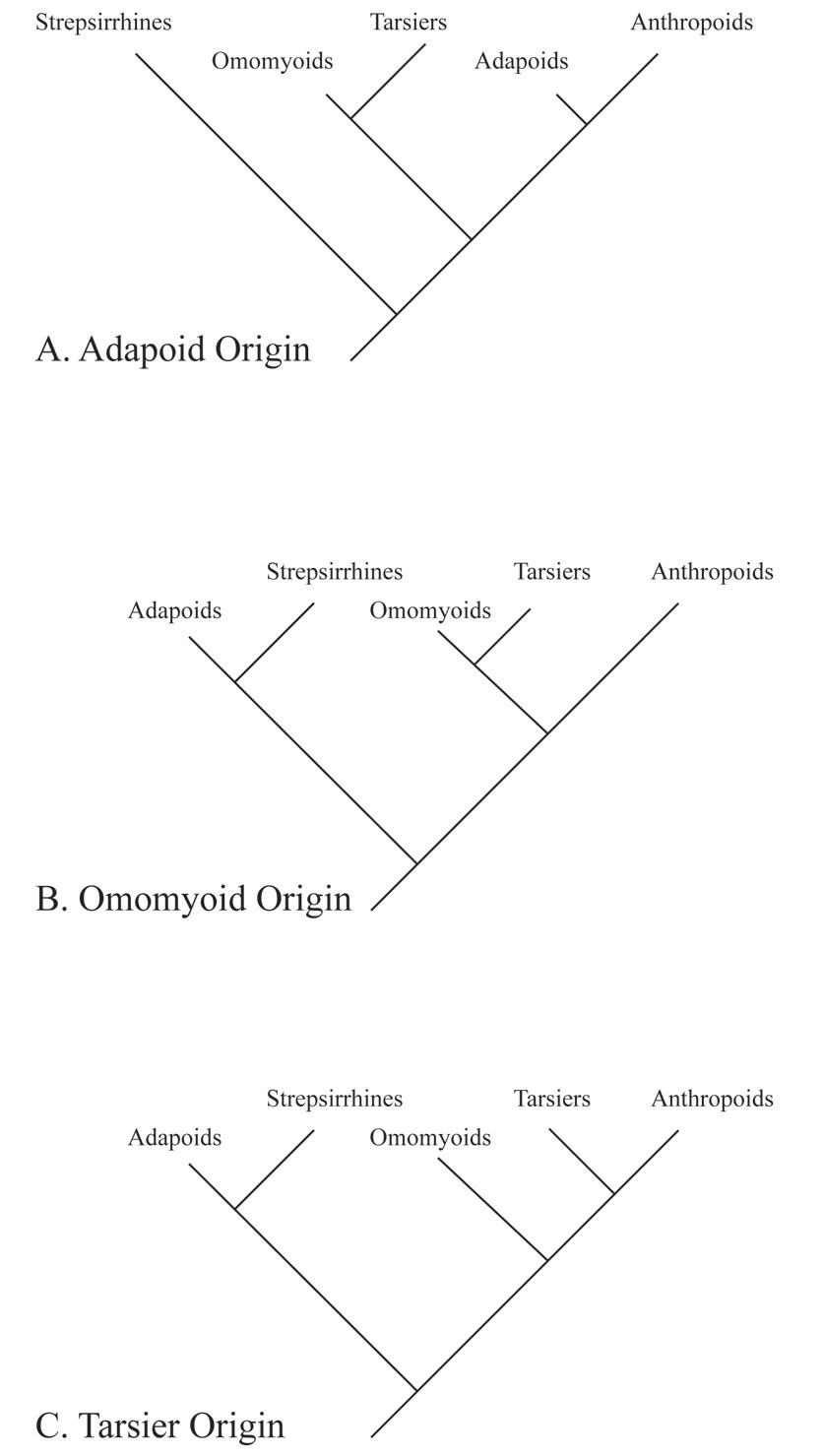

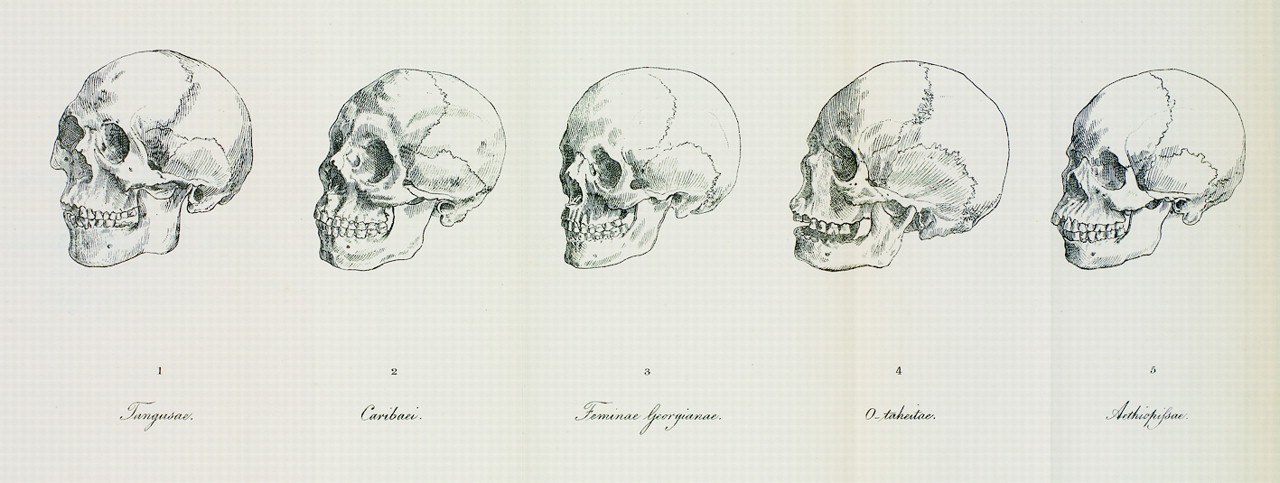

Competing Hypotheses for the Origin of Anthropoids

There is considerable debate among paleoanthropologists as to the geographic origins of anthropoids. In addition, there is debate regarding the source group for anthropoids. Three different hypotheses have been articulated in the literature. These are the adapoid origin hypothesis, the omomyoid origin hypothesis, and the tarsier origin hypothesis (Figure 8.13).

Adapoid Origin Hypothesis

Resemblances between some adapoids and some extant anthropoids include fusion of the mandibular symphysis, overall robusticity of the chewing system, overall large body size, features that signal a diurnal lifestyle (like relatively small eye sockets), and ankle bone morphology. Another feature in common is canine sexual dimorphism, which is present in some species of adapoids (probably) and in several species of anthropoids.

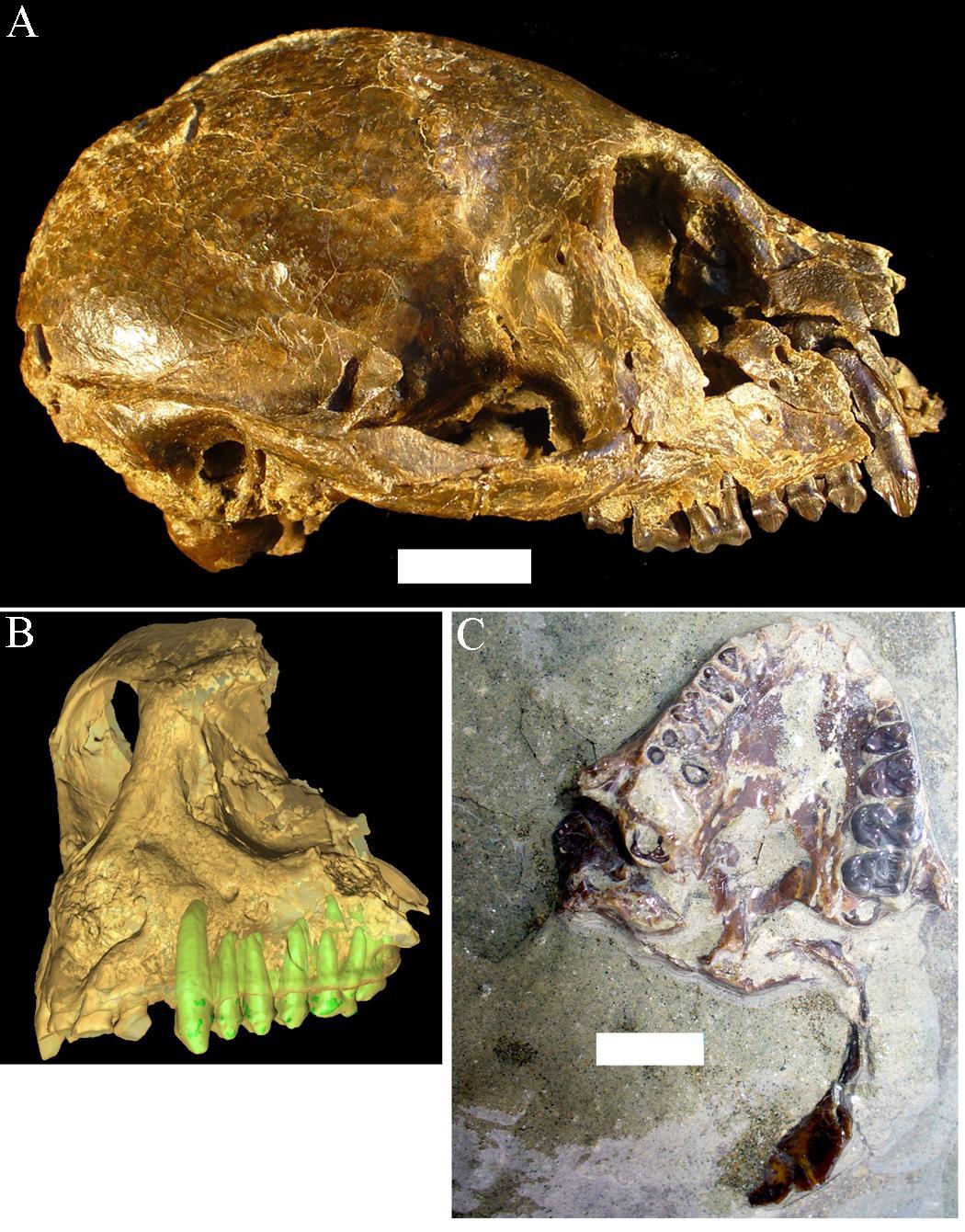

These features led some paleoanthropologists in the last half of the 20th century to suggest that anthropoids came from adapoid stock (Gingerich 1980; Simons and Rasmussen 1994b). One of the earliest supporters of the link between adapoids and anthropoids was Hans Georg Stehlin, who described much of the best material of adapoids and compared these Eocene primates to South American monkeys (Stehlin 1912). In more recent times, the adapoid origin hypothesis was reinforced by resemblances between these European adapoids (especially Adapis and Leptadapis) and some early anthropoids from the Fayum Basin (e.g., Aegyptopithecus, see below; Figure 8.14).

|

Family

|

Genera

|

Morphology

|

Location

|

Age1

|

|

Propliopithecidae2 |

Aegyptopithecus |

Large size. Cranial sexual dimorphism, large canines. Robust jaws and rounded molars. Partially ossified ear tube (in some). Robust skeleton; quadruped. |

Africa |

Late Eocene to Early Oligocene |

|

Parapithecidae3 |

Apidium |

Medium size. Retention of three premolars per quadrant. Rounded molars and premolars with large central cusps. Adaptations for leaping in the lower limb. |

Africa |

Late Eocene to Late Oligocene |

|

Proteopithecidae4 |

Proteopithecus |

Small size. Retention of three premolars per quadrant. Arboreal quadrupeds that ate fruit. |

Africa |

Late Eocene |

|

Oligopithecidae5 |

Catopithecus |

Small size. Skull has postorbital septum and unfused mandible. Deep jaws. Diet of fruits. Generalized quadruped. |

Africa |

Late Eocene |

|

Eosimiidae |

Eosimias |

Deep jaw with vertical unfused symphysis. Pointed incisors and canines. Crowded premolars. |

Asia |

Middle Eocene |

|

Amphipithecidae6 |

Pondaungia |

Deep jaws. Molars generally rounded with wide basins. |

Asia |

Middle Eocene to Early Oligocene |

|

1 Derived from Fleagle 2013. 2 See Gebo and Simons 1987 and Simons et al. 2007. 3 See Feagle and Simons 1995 and Simons 2001. 4 See Simons and Seiffert 1999. 5 See Simons and Rasmussen 1996. 6 See Kay et al. 2004. |

|

|||

Unfortunately for the adapoid hypothesis, most of the shared features listed above probably emerged independently in the two groups as adaptations to a diet of hard and/or tough foods. For example, fusion of the mandibular symphysis likely evolved as a means to strengthen the jaw against forces that would pull the two halves away from each other, in the context of active chewing muscles on both sides of the head generating great bite forces. This context would also favor the development of robust jaws, large chewing muscles, shorter faces, and some other features shared by some adapoids and some anthropoids.

As older and more plesiomorphic anthropoids were found in the Fayum Basin, it became clear that the earliest anthropoids from Africa did not possess these features of jaw robusticity (Seiffert et al. 2009). Furthermore, many adapoids never evolved these features. Fusion of the mandibular symphysis in adapoids is actually quite different from that in anthropoids and probably occurred during juvenile development in the former (Beecher 1983; Ravosa 1996). Eventually, the adapoid origin hypothesis fell out of favor among most paleoanthropologists, although the description of Darwinius is a recent revival of that idea (Franzen et al. 2009; but see Seiffert et al. 2009, Williams et al. 2010b).

Omomyoid Origin Hypothesis

Similarities in cranial and hindlimb morphology between some omomyoids and extant tarsiers have led to the suggestion that tarsiers arose from some kind of omomyoid. In particular, Necrolemur has many features in common with tarsiers, as does the North American Shoshonius, which is known from a few beautifully preserved (although distorted) crania. Tarsiers and Shoshonius share exclusively some features of the base of the cranium; however, Shoshonius does not have any sign of postorbital closure, and it lacks the bony ear tube of tarsiers. Nevertheless, some of the resemblances between some omomyoids and tarsiers suggest that tarsiers might have originated from within the Omomyoidea (Beard 2002; Beard and MacPhee 1994). In this scenario, although living tarsiers and living anthropoids might be sister taxa, they might have evolved from different omomyoids, possibly separated from each other by more than 50 million years of evolution, or from anthropoids evolved from some non-omomyoid fossil group. The arguments against the omomyoid origin hypothesis are essentially the arguments for the tarsier origin hypothesis (see below). Namely, tarsiers and anthropoids share many features (especially of the soft tissues) that must have been retained for many millions of years or must have evolved convergently in the two groups. Furthermore, a key hard-tissue feature shared between the two extant groups, the postorbital septum, was not present in any omomyoid. Therefore, that feature must have arisen convergently in the two extant groups or must have been lost in omomyoids. Neither scenario is very appealing, although recent arguments for convergent evolution of the postorbital septum in tarsiers and anthropoids have arisen from embryology and histology of the structure (DeLeon et al. 2016).

Tarsier Origin Hypothesis

Several paleoanthropologists have suggested that there is a relationship between tarsiers and anthropoids to the exclusion of omomyoids and adapoids (e.g., Cartmill and Kay 1978; Ross 2000; Williams and Kay 1995). Tarsiers and anthropoids today share several traits, including many soft-tissue features related to the olfactory system (e.g., the loss of a hairless external nose and loss of the median cleft running from the nose to the mouth, as possessed by strepsirrhines), and aspects of the visual system (e.g., the loss of a reflective layer at the back of the eye, similarities in carotid circulation to the brain, and mode of placentation). Unfortunately, none of these can be assessed directly in fossils. Some bony similarities between tarsiers and anthropoids include an extra air-filled chamber below the middle ear cavity, reduced bones within the nasal cavity, and substantial postorbital closure; these can be assessed in fossils, but the distribution of these traits in omomyoids does not yield clear answers. Furthermore, several similarities between tarsiers and anthropoids are probably due to similarities in sensory systems, which might have evolved in parallel for ecological reasons. Although early attempts to resolve the crown primates with molecular data were sometimes equivocal or in disagreement with one another, more recent analyses (including those of short interspersed elements) suggest that tarsiers and anthropoids are sister groups to the exclusion of lemurs and lorises (Williams et al. 2010a). However, this does not address omomyoids, all of which are far too ancient for DNA extraction.

The above three hypotheses are not the only possibilities for anthropoid origins. It may be that anthropoids are neither the closest sister group of tarsiers, nor evolved from adapoids or omomyoids. In recent years, two new groups of Eocene Asian primates have been implicated in the origin of anthropoids: the eosimiids and the amphipithecids. It is possible that one or the other of these two groups gave rise to anthropoids. Regardless of the true configuration of the tree for crown primates, the three major extant groups probably diverged from each other quite long ago (Seiffert et al. 2004).

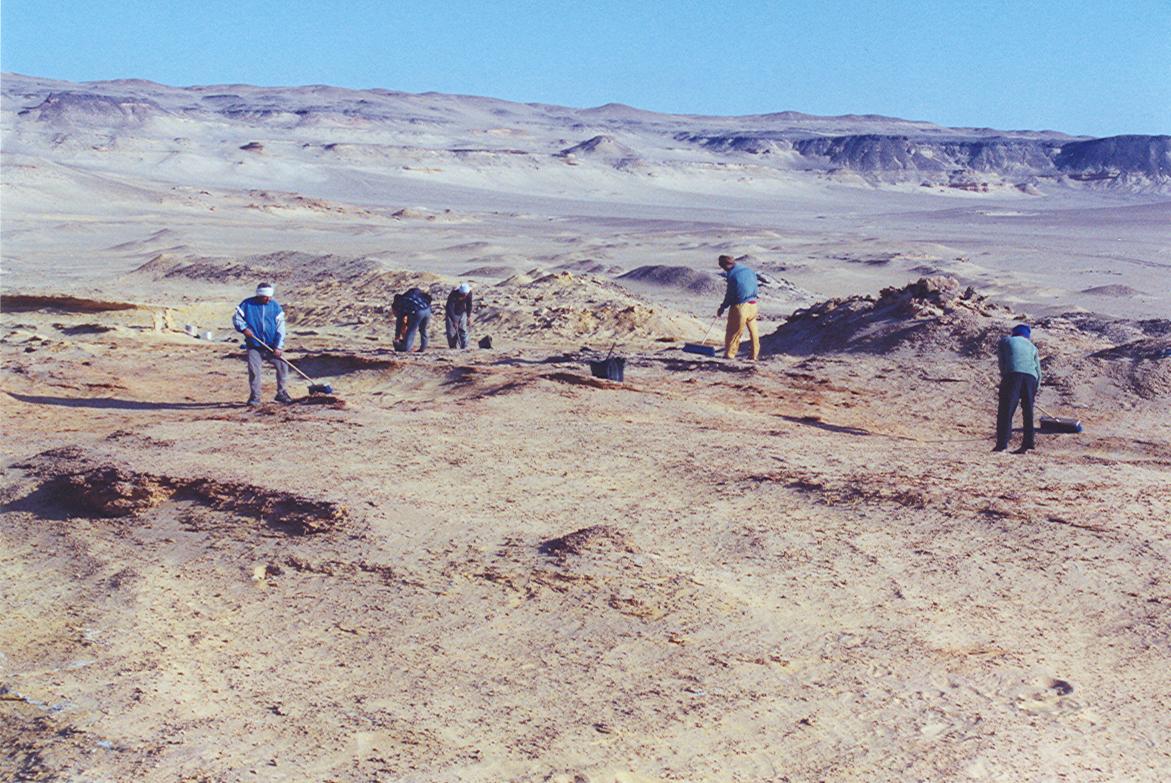

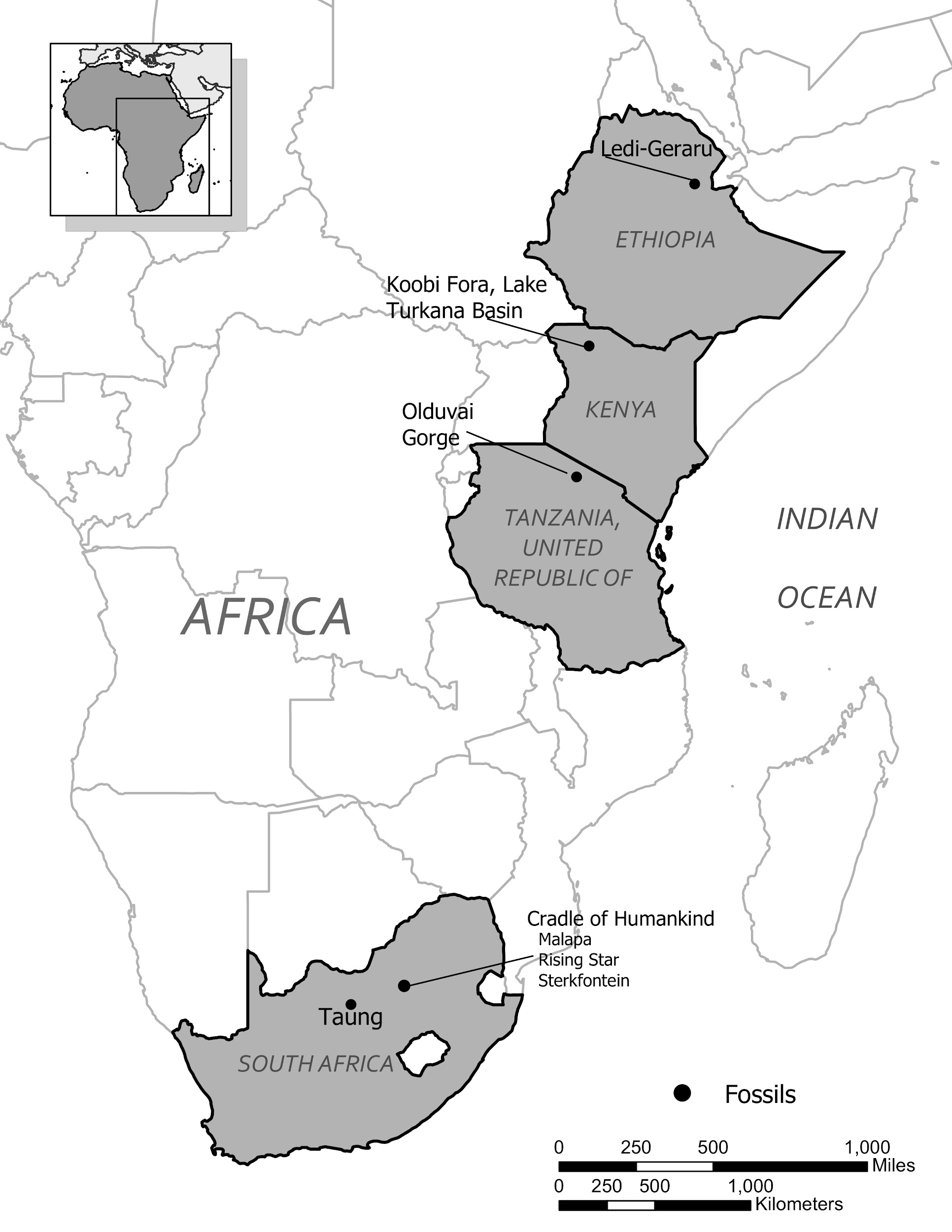

Early Anthropoid Fossils in Africa

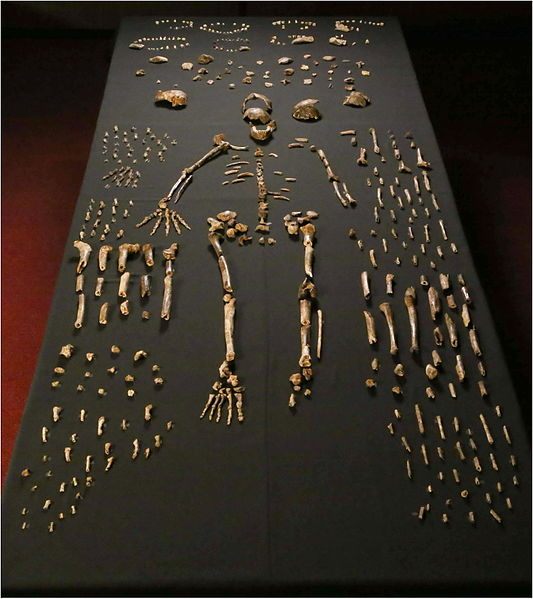

The classic localities yielding the greatest wealth of early anthropoid fossils are those from the Fayum Basin in Egypt (Simons 2008; Figure 8.15). The Fayum is a veritable oasis of fossil primates in an otherwise spotty early Tertiary African record. Since the 1960s, teams led by E. L. Simons have discovered several new species of early anthropoids, some of which are known from many parts of the skeleton and several individuals (Figure 8.16).

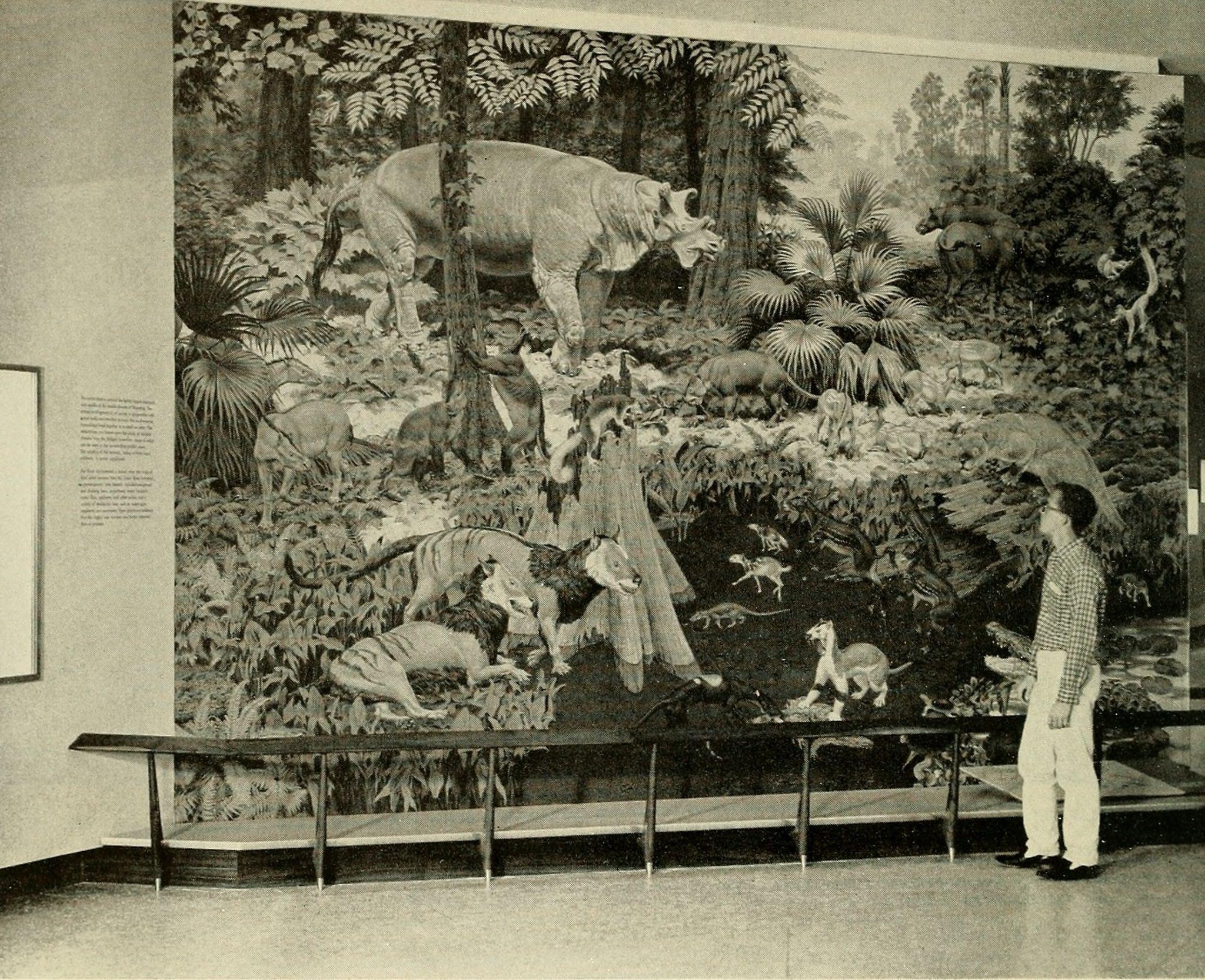

The Fayum Jebel Qatrani Formation and Birket Qarun Formation between them have yielded a remarkable array of terrestrial, arboreal, and aquatic mammals. These include ungulates, bats, sea cows, elephants, hyraces, rodents, whales, and primates. Also, many other vertebrates, like water birds, were present. The area at the time of deposition (Late Eocene through Early Oligocene) was probably very wet, with slow-moving rivers, standing water, swampy conditions, and lots of trees (see Bown and Kraus 1988). In short, it was an excellent place for primates.

General Morphology of Anthropoids

The anthropoids known from the Fayum (and their close relatives from elsewhere in East Africa and Afro-Arabia) bear many of the anatomical hallmarks of extant anthropoids; however, there are plesiomorphic forms in several families that lack one or more anthropoid traits. All Fayum anthropoids known from skulls possess postorbital closure, most had fused mandibular symphyses, and most had ring-like ectotympanic bones. Tooth formulae were generally either 2.1.3.3 or 2.1.2.3. Fayum anthropoids ranged in size from the very small Qatrania and Biretia (less than 500 g) to the much-larger Aegyptopithecus (approximately 7 kg; 15 lbs.). Fruit was probably the main component of the diet for most or all of the anthropoids, with some of them supplementing with leaves (Kay and Simons 1980; Kirk and Simons 2001; Teaford et al. 1996). Most Fayum anthropoids were probably diurnal above-branch quadrupeds. Some of them (e.g., Apidium; see Figure 8.14) were probably very good leapers (Gebo and Simons 1987), but none show specializations for gibbon-style suspensory locomotion. Some of the Fayum anthropoids are known from hundreds of individuals, permitting the assessment of individual variation, sexual dimorphism, and in some cases growth and development. The description that follows provides greater detail for the two best known Fayum anthropoid families, the Propliopithecidae and the Parapithecidae; the additional families are summarized briefly.

Fayum Anthropoid Families

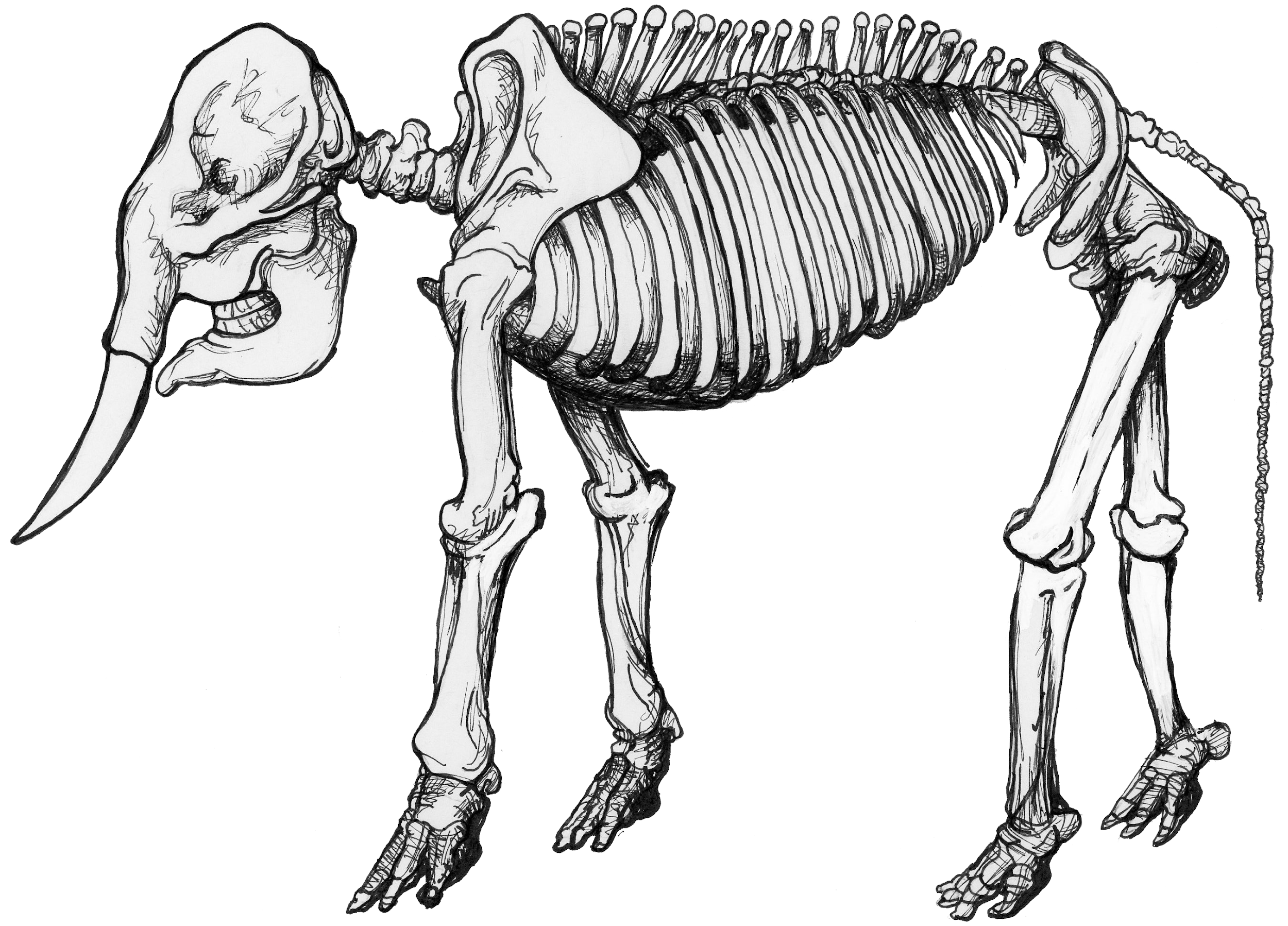

The Propliopithecidae (see Figure 8.14) include the largest anthropoids from the fauna, and they are known from several crania and some postcranial elements. They have been suggested to be stem catarrhines, although perhaps near the split between catarrhines and platyrrhines. The best known propliopithecid is Aegyptopithecus, known from many teeth, crania, and postcranial elements (Figure 8.17) .

Parapithecidae are an extremely abundant and unusual family of anthropoids from the Fayum. The parapithecid Apidium is known from many jaws with teeth, crushed and distorted crania, and several skeletal elements. Parapithecus is known from cranial material including a beautiful, undistorted cranium. This genus shows extreme reduction of the incisors, including complete absence of the lower incisors in P. grangeri (Simons 2001). This trait is unique among primates. Parapithecids were once thought to be the ancestral stock of platyrrhines; however, their platyrrhine-like features are probably ancestral retentions, so the most conservative approach is to consider them stem anthropoids.

The Proteopithecidae were small frugivores that probably mainly walked along horizontal branches on all fours. TThey are considered stem anthropoids. The best known genus, Proteopithecus, is represented by dentitions, crania, and postcranial elements.

The Oligopithecidae share a mixture of traits that makes them difficult to classify more specifically within anthropoids. The best known member, Catopithecus, is known from crania that demonstrate a postorbital septum and from mandibles that lack symphyseal fusion. They share the catarrhine tooth formula of 2.1.2.3 and have a canine honing complex that involves the anterior lower premolar. The postcranial elements known for the group suggest generalized arboreal quadrupedalism. The best known member, Catopithecus, is known from crania that demonstrate a postorbital septum and from mandibles that lack symphyseal fusion (Simons and Rasmussen 1996). The jaws are deep, with broad muscle attachment areas and crested teeth. Catopithecus was probably a little less than a kilogram in weight.

Other genera of putative anthropoids from the Fayum include the very poorly known Arsinoea, the contentious Afrotarsius, and the enigmatic Nosmips. The last of these possesses traits of several major primate clades and defies classification (Seiffert et al. 2010).

Early Anthropoid Fossils in Asia

For the last half of the 1900s, researchers believed that Africa was the unquestioned homeland of early anthropoids (see Fleagle and Kay 1994). However, two very different groups of primates from Asia soon began to change that. One was an entirely new discovery (Eosimiidae), and the other was a poorly known group discovered decades prior (Amphipithecidae). Soon, attention on anthropoid origins began to shift eastward (see Ross and Kay 2004; Simons 2004). If anthropoids arose in Asia instead of Africa, then this implies that the African early anthropoids either emigrated from Asia or evolved their anthropoid traits in parallel with living anthropoids.

Eosimiids

First described in the 1990s, the eosimiids are best represented by Eosimias (see Figure 8.14; Figure 8.18). This tiny “dawn monkey” is known from relatively complete jaws with teeth, a few small fragments of the face, and some postcranial elements (Beard et al. 1994; Beard et al. 1996; Gebo et al. 2000). Eosimias (along with the other less-well-known genera in its family) bears some resemblance to tarsiers as well as anthropoids. Unfortunately, no good crania are known for this family, and the anatomy of, for example, the posterior orbital margin could be very revealing as to higher-level relationships.

Amphipithecids

Amphipithecids are small- to medium-size primates (up to 10 kg; 22 lbs.). Most are from the Eocene Pondaung Formation in Myanmar (Early–Middle Eocene), but one genus is known from Thailand. Some dental similarities with anthropoids were noted early on, such as deep jaws and wide basins that separate low molar cusps. The best known genera were Pondaungia and Amphipithecus (Ciochon and Gunnell 2002; see Figure 8.14). Another amphipithecid, Siamopithecus from Thailand, has very rounded molars and was probably a seed-eater (Figure 8.19). In addition to teeth and jaws, some cranial fragments, ankle material, and ends of postcranial bones have been found for Pondaungia. There are important resemblances between the postcranial bones of Pondaungia and those of adapoids, suggesting adapoid affinities for the amphipithecidae. This would imply that the resemblances with anthropoids in the teeth are convergent, based on similarities in diet (see Ciochon and Gunnell 2002). Unfortunately, the association between postcranial bones and teeth is not definite. With other primates in these faunas (including eosimiids), one cannot be certain that the postcranial bones belong with the teeth. Some researchers suggest that some bones belong to a sivaladapid (or asiadapid) and others to an early anthropoid (Beard et al. 2007; Marivaux et al. 2003). Additional well-associated material of amphipithecids would help to clear up this uncertainty.

Platyrrhine Dispersal to South America

Today there is an impressive diversity of primates in South and Central America. These are considered to be part of a single clade, the Platyrrhini. Primates colonized South America sometime in the Eocene from an African source. In the first half of the 20th century, the source of platyrrhines was a matter of major debate among paleontologists, with some favoring a North American origin (e.g., Simpson 1940).

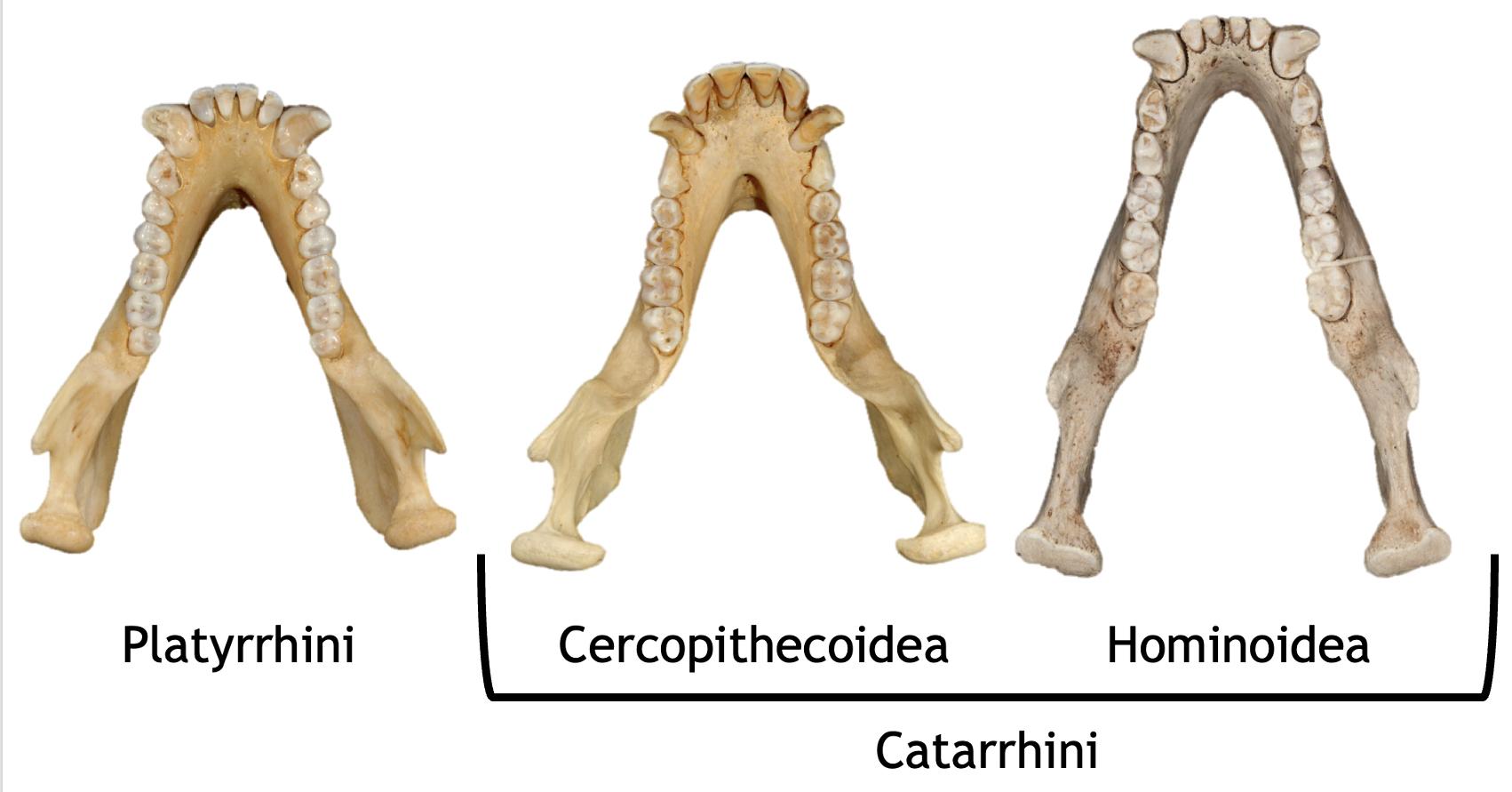

Part of the reason for this debate is that South America was an island in the Eocene. Primates needed to cross open ocean to get there from either North America or Africa, although the distance from the former was shorter. Morphology yields clues to platyrrhine origins. The first known primates in South America have more in common morphologically with African primates than with North American ones. At the time, anthropoids were popping up in North Africa, whereas the only euprimates in North America were adapoids and omomyoids. Despite lacking a bony ear tube, early platyrrhines shared a great deal with other anthropoids, including full postorbital closure and fusion of the mandibular symphysis.

The means by which a population of small North African primates managed to disperse across the Atlantic and survive to colonize South America remains a mystery. The most plausible scenario is one of rafting. That is, primates must have been trapped on vegetation that was blown out to sea by a storm. The vegetation then became a sort of life raft, which eventually landed ashore, dumping its passengers in South America. Rodents probably arrived in South America in the same way (Antoine et al. 2012).

Once ashore, platyrrhines must have crossed South America fairly rapidly because the earliest-known primates from that continent are from Peru (Bond et al. 2015). Soon after that, platyrrhines were in Bolivia, namely Branisella. By the Miocene, platyrrhines were living in extreme southern Argentina and were exploiting a variety of feeding niches. The Early Miocene platyrrhines were all somewhat plesiomorphic in their morphology, but some features that likely arose by ecological convergence suggest (to some) relationships with extant platyrrhine families. This has led to a lively debate about the pattern of primate evolution in South America (Kay 2015; Kay and Fleagle 2010; Rosenberger 2010). By the Middle Miocene, clear representatives of modern families were present in a diverse fauna from La Venta, Colombia (Wheeler 2010). The Plio-Pleistocene saw the emergence of giant platyrrhines as well as several taxa of platyrrhines living on Caribbean islands (Cooke et al. 2016).

The story of platyrrhines seems to be one of amazing sweepstakes dispersal, followed by rapid diversification and widespread geographic colonization of much of South America. After that, dramatic extinctions resulted in the current, much-smaller geographic distribution of platyrrhines. These extinctions were probably caused by changing climates, leading to the contraction of forests. Platyrrhines dispersed to the Caribbean and to Central America, with subsequent extinctions in those regions that might have been related to interactions with humans. Unlike anthropoids of Africa and Asia, platyrrhines do not seem to have evolved any primarily terrestrial forms and so have always been highly dependent on forests.

Special Topic: Jonathan Perry and Primates of the Extreme South

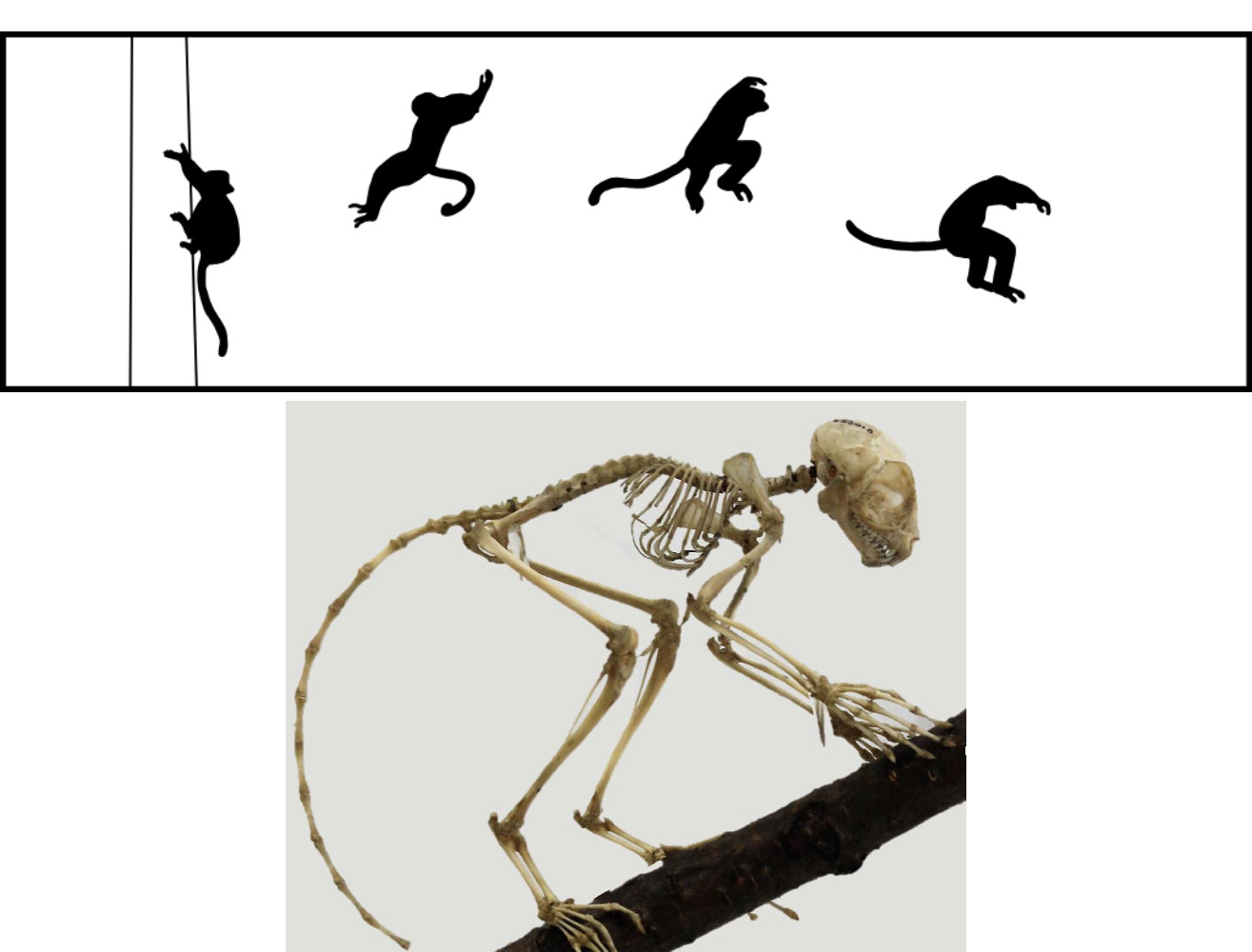

Many primates are very vulnerable to ecological disturbance because they are heavily dependent on fruit to eat and trees to live in. This is one reason why so many primates are endangered today and why many of them went extinct due to climatic and vegetational changes in the past. I (Jonathan Perry) have conducted paleontological research focusing on primates that lived on the edge of their geographic distribution. This research has taken me to extreme environments in the Americas: southern Patagonia, the Canadian prairies, western Wyoming, and the badlands of eastern Oregon.

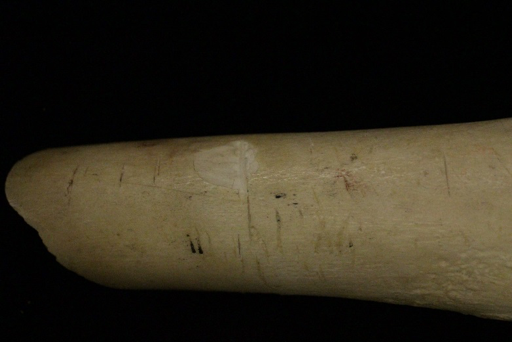

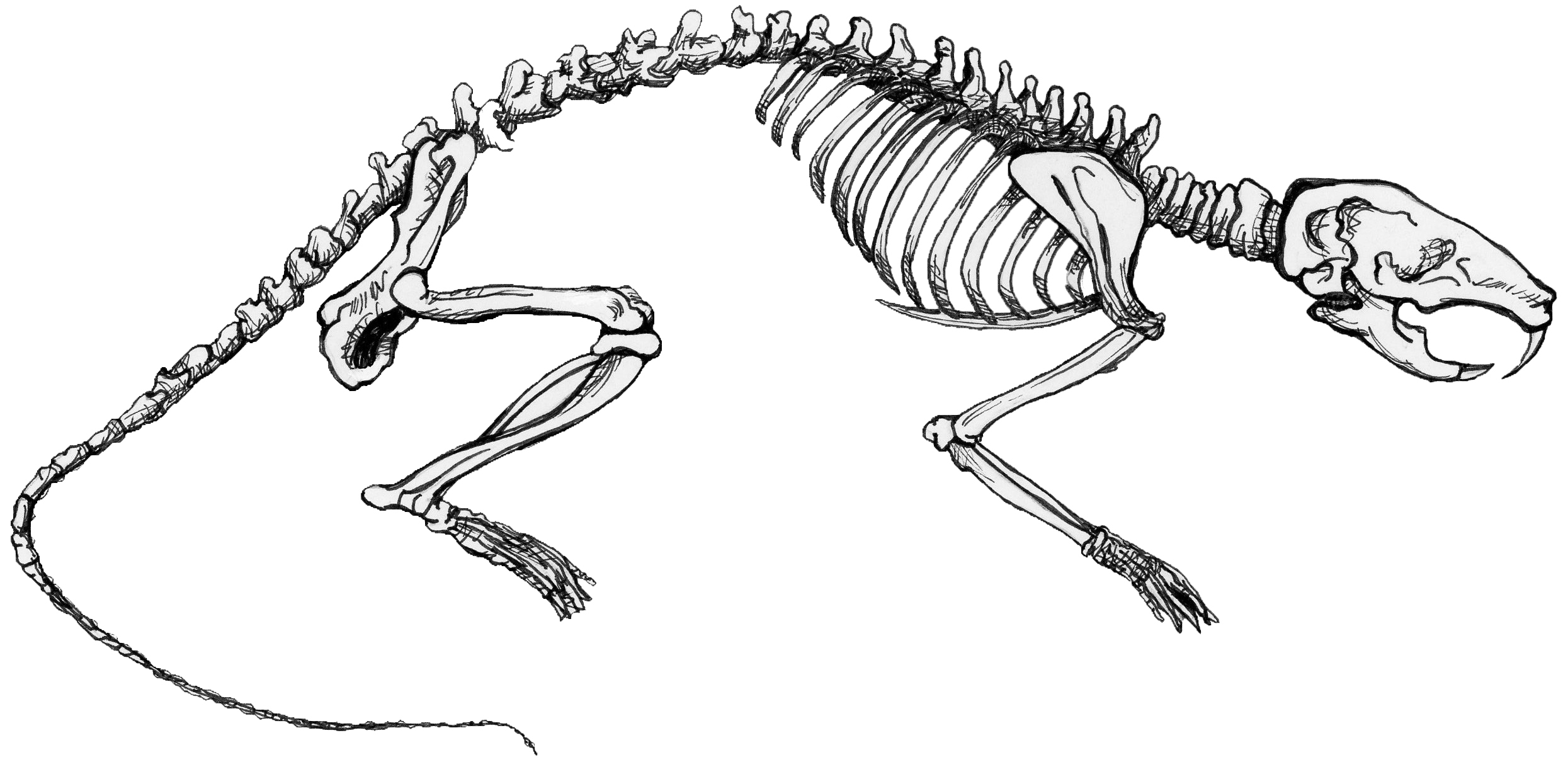

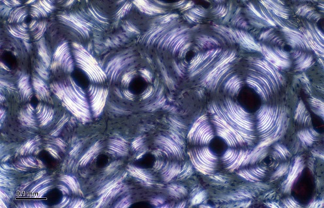

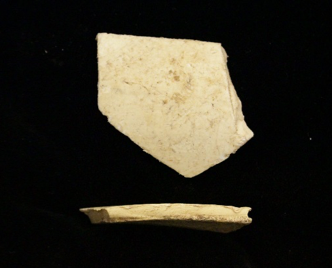

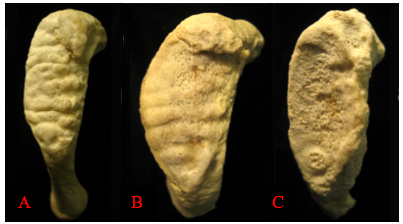

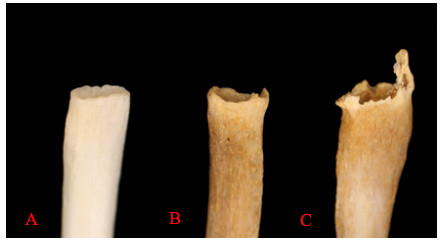

Santa Cruz Province in Argentina is as far south as primates have ever lived. The Santa Cruz fauna of the Miocene has yielded a moderate diversity of platyrrhines, each with slightly different dietary adaptations. These include Homunculus, first described by Florentino Ameghino in 1891 (Figure 8.20). Recent fieldwork by my colleagues and I in Argentina has revealed several skulls of Homunculus as well as many parts of the skeleton (Kay et al. 2012). The emerging profile of this extinct primate is one of a dedicated arboreal quadruped that fed on fruits and leaves. Many of the foods eaten by Homunculus must have been very tough and were probably covered and impregnated with grit; we suspect this because the cheek teeth are very worn down, even in young individuals, and because the molar tooth roots were very large, presumably to resist strong bite forces (Perry et al. 2010, 2014).

I began working in Argentina while a graduate student at Duke University. I participated as a field assistant in a team led by my Ph.D. advisor, Richard F. Kay, and Argentine colleagues Sergio F. Vizcaíno and M. Susana Bargo. Most of the localities examined belong to a suite of beach sites known since the 1800s and visited by many field parties from various museums in the early 1900s. Since 2003, our international team of paleontologists from the U.S. and Argentina has visited these localities every single year (Figure 8.21). Over time, new fossils and new students have led to new projects and new approaches, including the use of microcomputed tomography (microCT) to visualize and analyze internal structures of the skeleton.

Planet of Apes

Geologic Activity and Climate Change in the Miocene

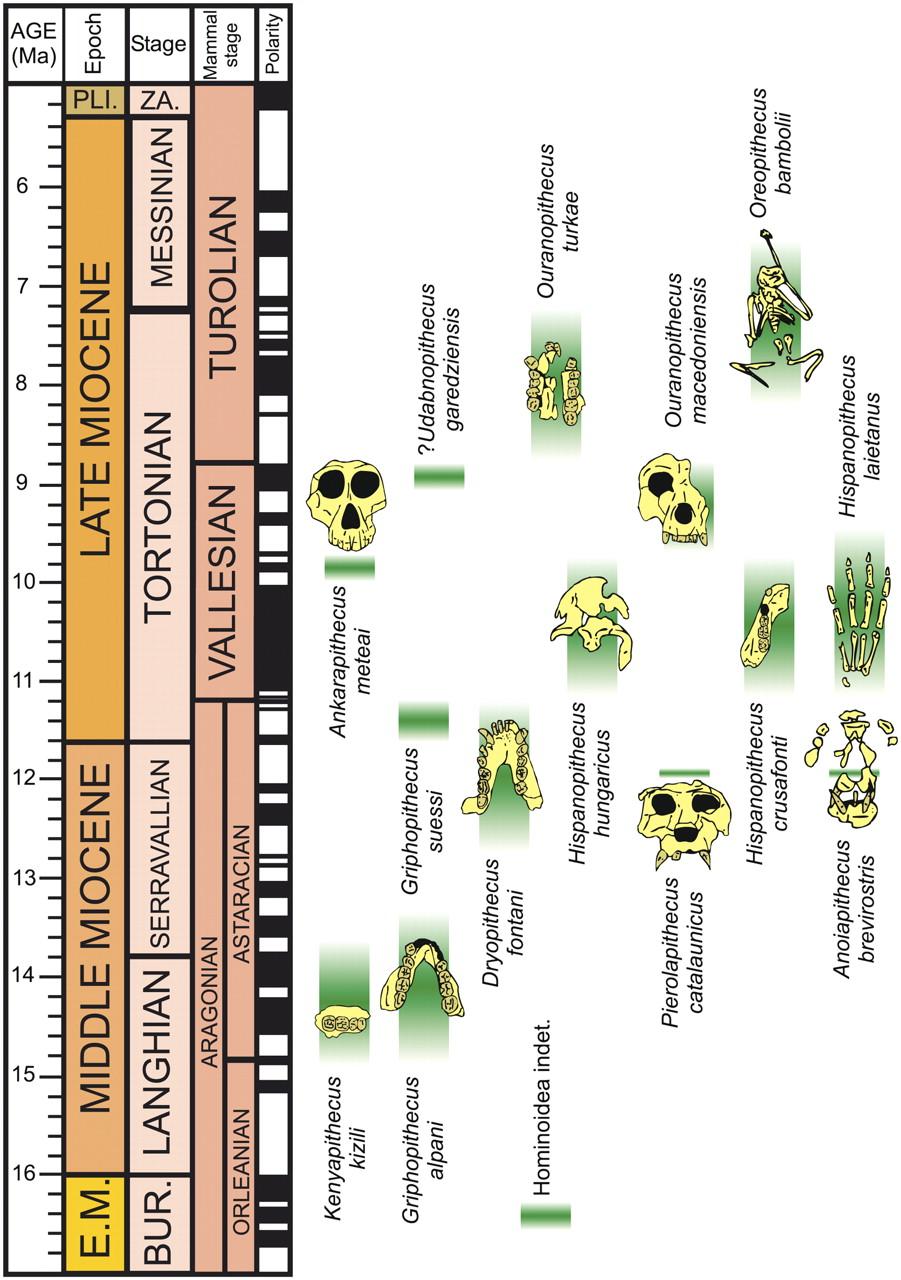

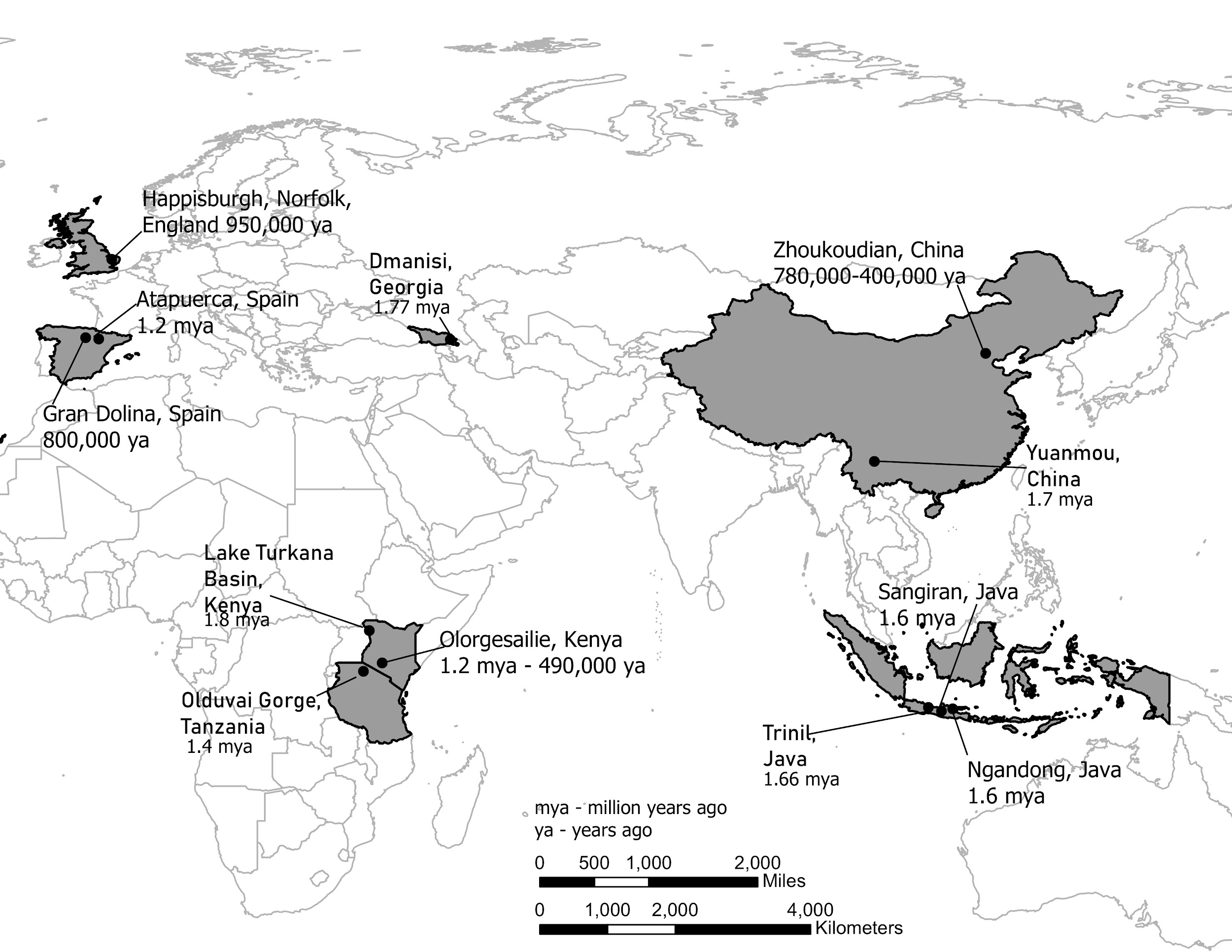

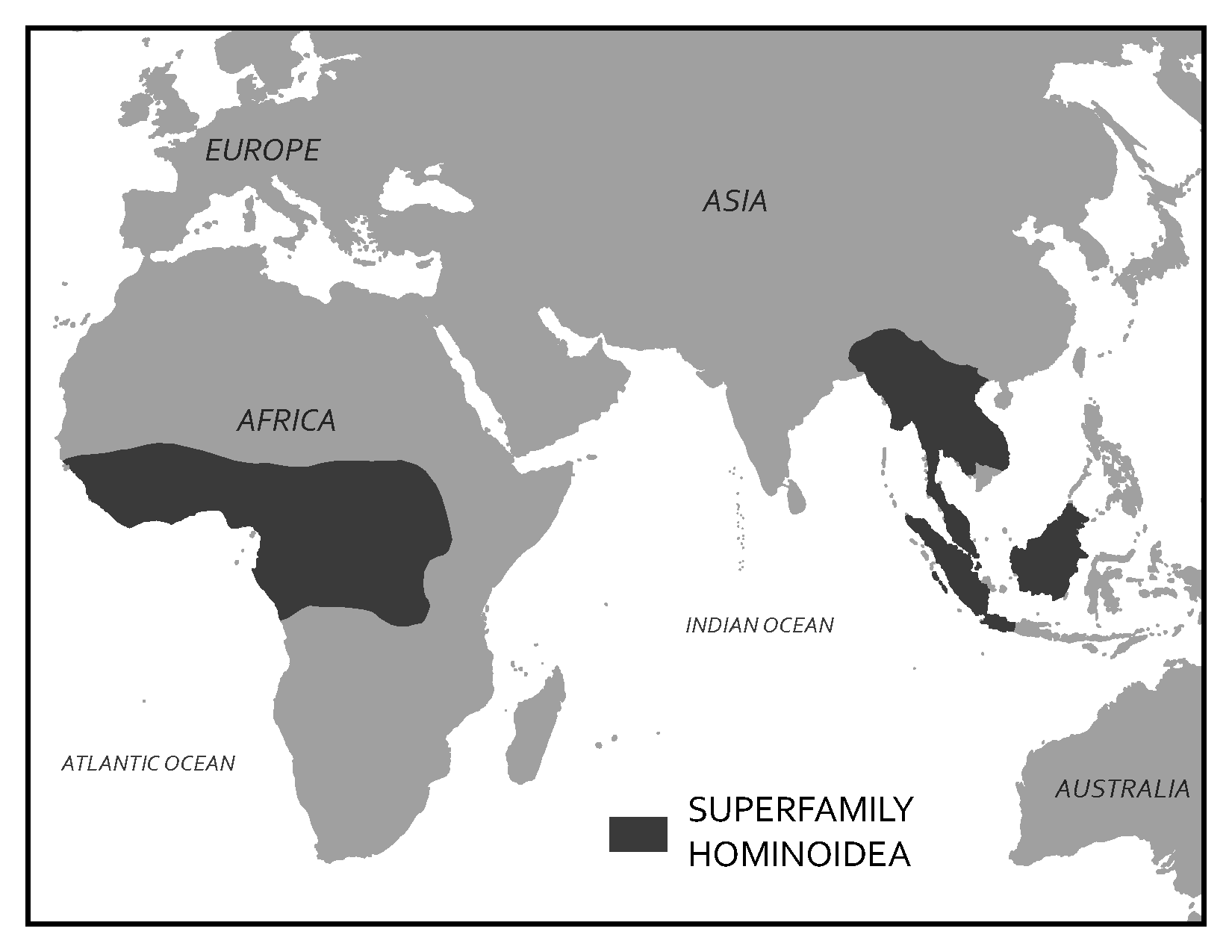

The Miocene Epoch was a time of mammalian diversification and extinction, global climate change, and ecological turnover. In the Miocene, there was an initial warming trend across the globe with the expansion of subtropical forests, followed by widespread cooling and drying with the retreat of tropical forests and replacement with more open woodlands and eventually grasslands. It was also a time of major geologic activity. On one side of the globe, South America experienced the rise of the Andes Mountains. On the other side, the Indian subcontinent collided with mainland Asia, resulting in the rise of the Himalayan Mountains. In Africa, volcanic activity promoted the development of the East African Rift System. Critical to the story of ape evolution was the exposure of an intercontinental landbridge between East Africa and Eurasia, permitting a true planet of apes (Figure 8.22).

Geographic Distribution: Africa, Asia, Europe

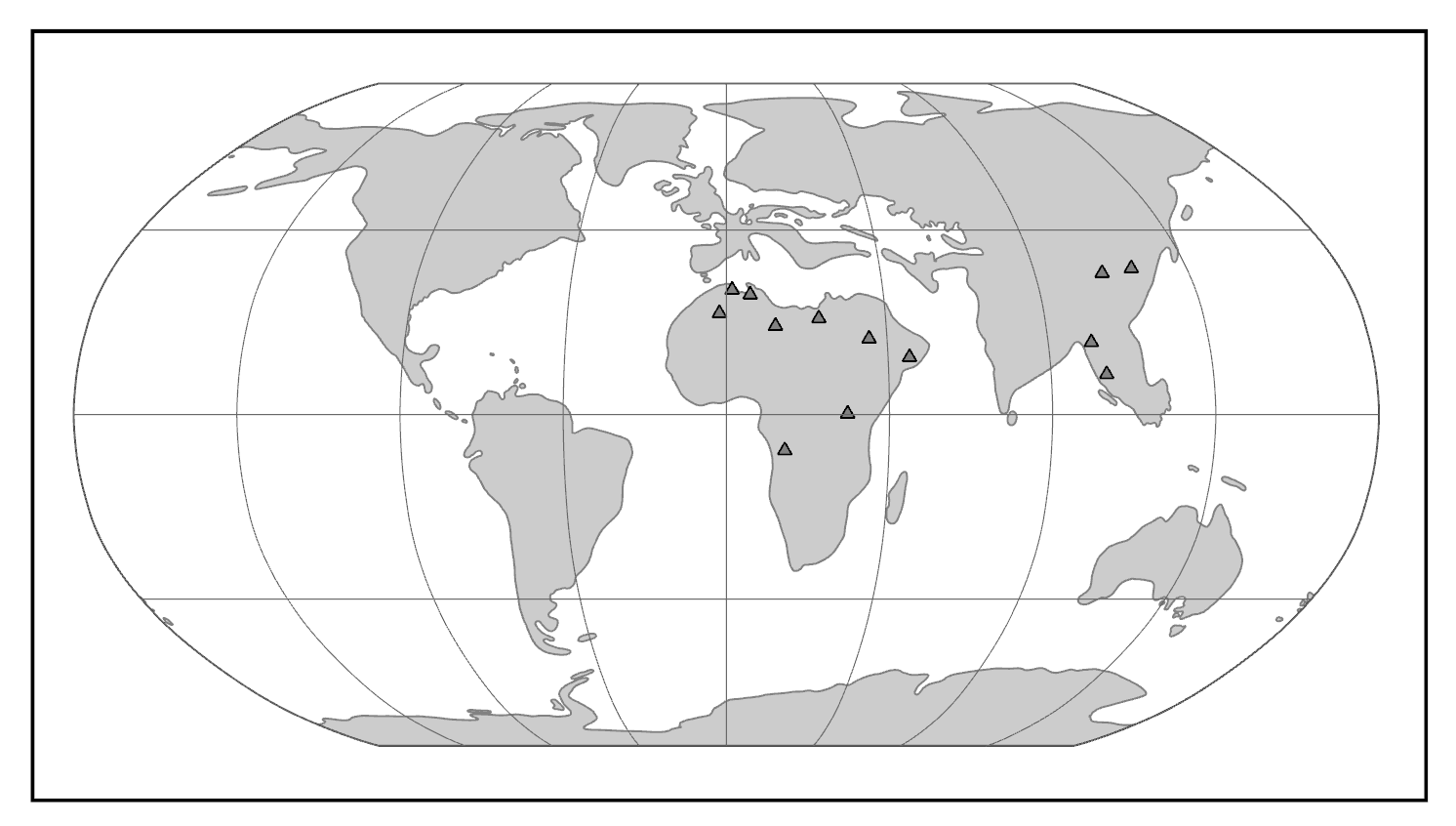

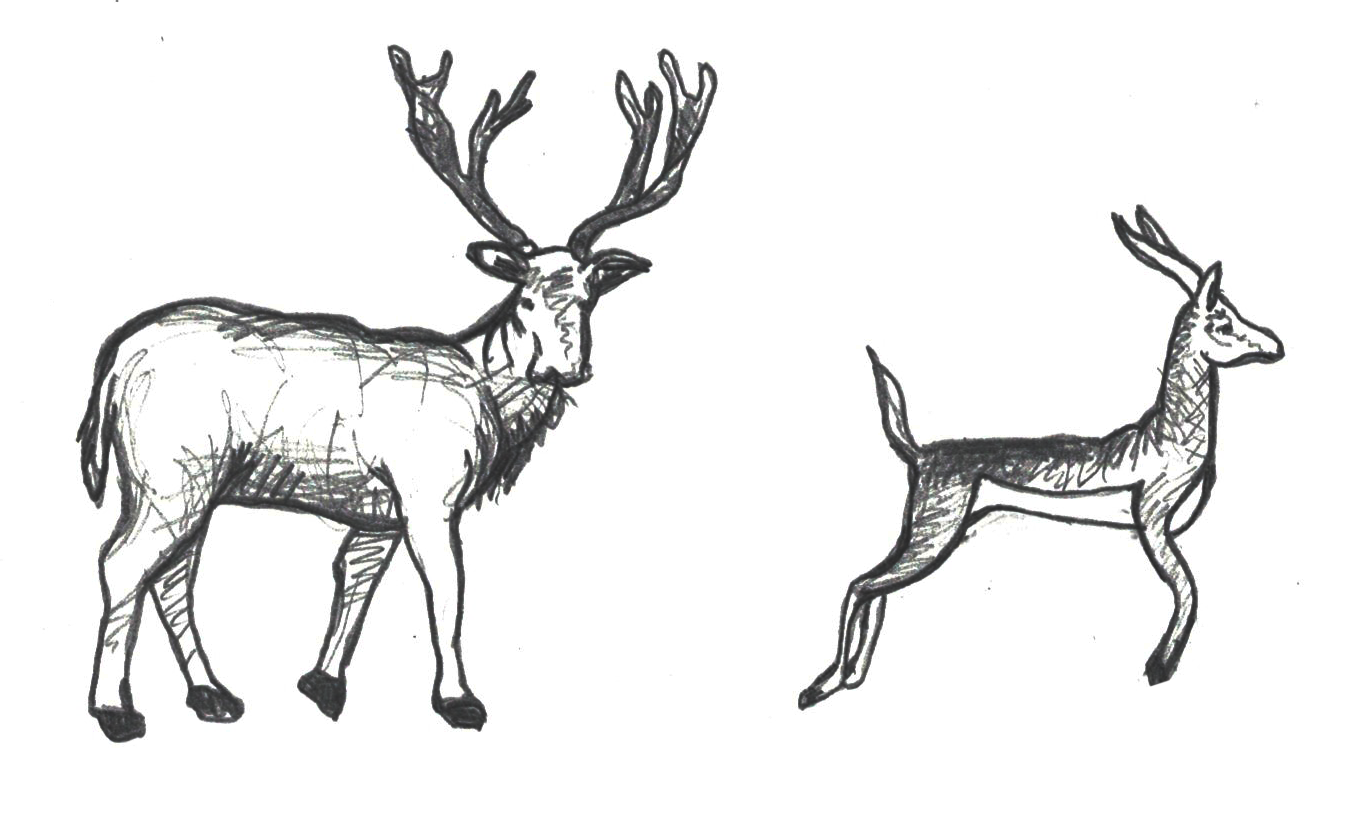

The world of the Miocene had tremendous ape diversity compared to today. The earliest records of fossil apes are from Early Miocene deposits in Africa. However, something dramatic happened around 16 million years ago. With the closure of the ancient Tethys Sea, the subsequent exposure of the Gomphotherium Landbridge, and a period of global warming, the Middle–Late Miocene saw waves of emigration of mammals (including primates) out of Africa and into Eurasia, with evidence of later African re-entry for some (Harrison 2010). Some of the mammals that dispersed from Africa to Eurasia and back were apes. Though most of these early apes left no modern descendants, some of them gave rise to the ancestors of modern apes—including hominins (Figure 8.23).

Where Are the Monkeys? Diversity in the Miocene

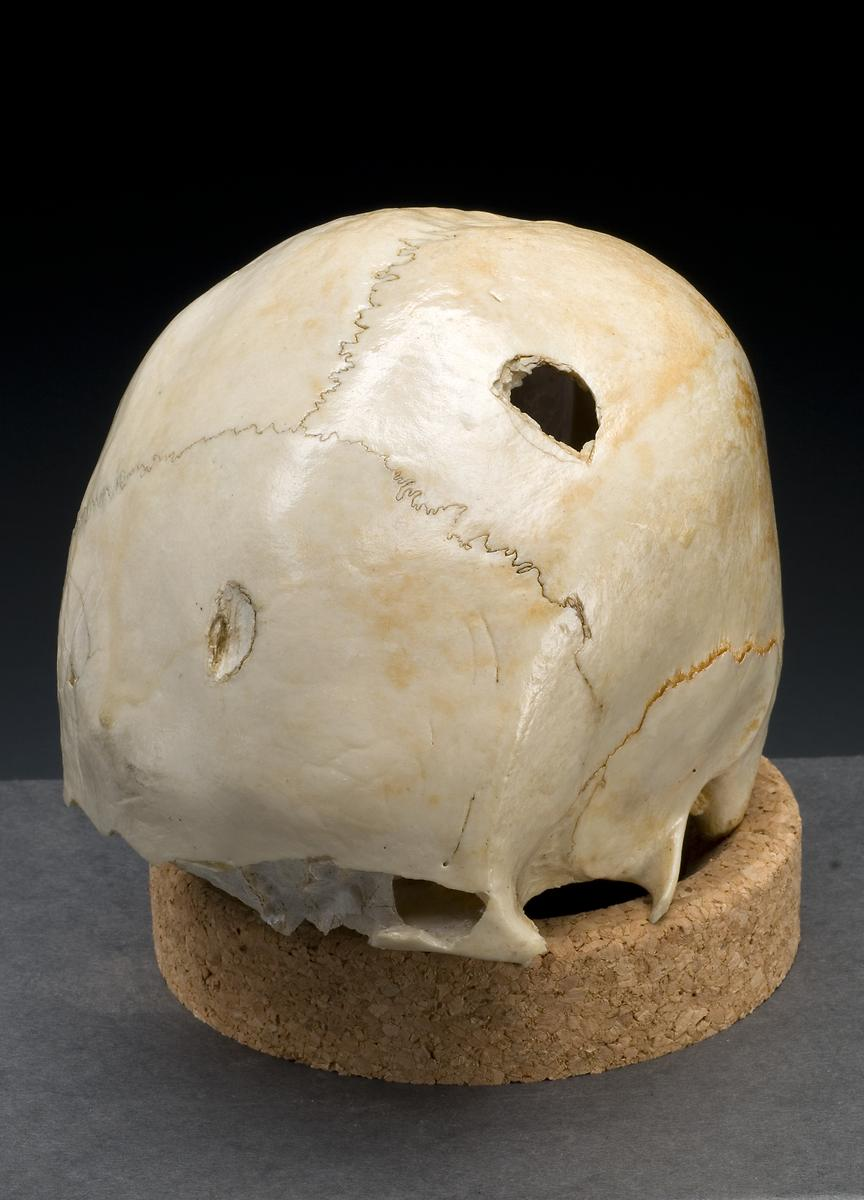

Whereas the Oligocene deposits in the Fayum of Egypt have yielded the earliest-known catarrhine fossils, the Miocene demonstrates some diversification of Cercopithecoidea. However, compared to the numerous and diverse Miocene apes (see below), monkeys of the Miocene are very rare and restricted to a single extinct family, the Victoriapithecidae (Figure 8.24). This family contains the earliest definite cercopithecoids. These monkeys are found from northern and eastern Africa between 20 million and 12.5 million years ago (Miller et al. 2009). The best known early African monkey is Victoriapithecus (Figure 8.25), a small-bodied (approximately 7 kg; 15 lbs.), small-brained monkey. Bilophodonty, known to be a hallmark of molar teeth of modern cercopithecoid, was present to some extent in Victoriapithecids. Victoriapithecus has been reconstructed as being more frugivorous and perhaps spent more time on the ground (terrestrial locomotion) than in the trees (arboreal locomotion; Blue et al. 2006). The two major groups of cercopithecoids today are cercopithecines and colobines. The earliest records demonstrating clear members of each of these two groups are at the end of the Miocene. Examples include the early colobine Microcolobus from Kenya and the early cercopithecine Pliopapio from Ethiopia.

|

Family

|

Genera

|

Morphology

|

Location

|

Age1

|

|

Victoriapithecidae2 |

Victoriapithecus |

Long, sloping face. Round, narrowly spaced orbits. Deep cheek bones. Well-developed sagittal crest. |

Africa |

Early to Middle Miocene |

|

Proconsulidae3 |

Proconsul |

Short face. Generalized dentition. Arboreal quadruped. Probably tailless. |

Africa and Arabia |

Early to Middle Miocene |

|

Pongidae |

Gigantopithecus |

Largest primate ever. Deep jaws and low rounded molars. |

Asia |

Miocene to Present |

|

1 Derived from Fleagle 2013. 2 See Benefit and McCrossin 1997 and Fleagle 2013. 3 See Begun 2007. |

|

|||

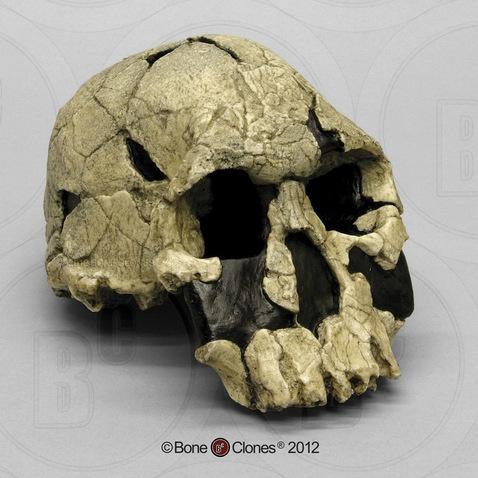

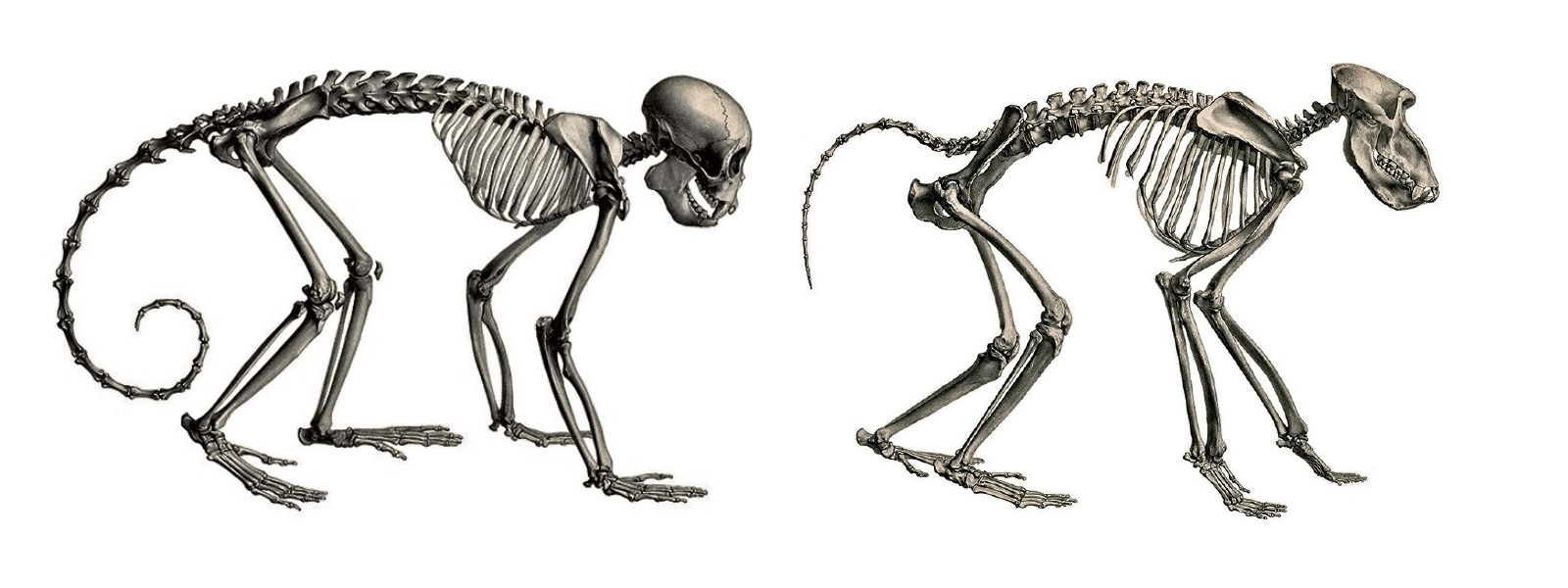

The Story of Us, the Apes

African Ape Diversity

The Early Miocene of Africa has yielded around 14 genera of early apes (Begun 2003). Many of these taxa have been reconstructed as frugivorous arboreal quadrupeds (Kay 1977). One of the best studied of these genera is the East African Proconsul (Family Proconsulidae; see Figure 8.24). Several species have been described, with body mass reconstructions ranging from 17 to 50 kg (approximately 37–110 lbs.). A paleoenvironmental study reconstructed the habitat of Proconsul to be a dense, closed-canopy tropical forest (Michel et al. 2014). No caudal vertebrae (tail bones) have been found in direct association with Proconsul postcrania, and the morphology of the sacrum is consistent with Proconsul lacking a tail (Russo 2016; Ward et al. 1991).

Overall, the African ape fossil record in the Late Miocene is sparse, with seven fossil localities dating between eleven and five million years ago (Pickford et al. 2009). Nevertheless, most species of great apes live in Africa today. Where did the progenitors of modern African apes arise? Did they evolve in Africa or somewhere else? The paucity of apes in the Late Miocene of Africa stands in contrast to the situation in Eurasia. There, ape diversity was high. Furthermore, several Eurasian ape fossils show morphological affinities with modern hominoids (apes). Because of this, some paleoanthropologists suggest that the ancestors of modern African great apes recolonized Africa from Eurasia toward the end of the Miocene (Begun 2002). However, discoveries of Late Miocene hominoids like the Kenyan Nakalipithecus (9.9 million to 9.8 million years ago), the Ethiopian Chororapithecus (10.7 million to 10.1 million years ago), and the late-Middle Miocene Namibian Otavipithecus (13 million to 12 million years ago) fuel an alternative hypothesis—namely that African hominoid diversity was maintained throughout the Miocene and that one of these taxa might, in fact, be the last common ancestor of extant African apes (Kunimatsu et al. 2007; Mocke et al. 2002). The previously underappreciated diversity of Late Miocene apes in Africa might be due to poor sampling of the fossil record in Africa.

Eurasian Ape Diversity

With the establishment of the Gomphotherium Landbridge (a result of the closure of the Eastern Mediterranean seaway; Rögl 1999), the Middle Miocene was an exciting time for hominoid radiations outside of Africa (see Figure 8.23). Eurasian hominoid species exploited their environments in many different ways in the Miocene. Food exploitation ranged from soft-fruit feeding in some taxa to hard-object feeding in others, in part owing to seasonal fluctuations and the necessary adoptions of fallback foods (DeMiguel et al. 2014). For example, the molars of Oreopithecus bambolii (Family Hominidae) have relatively long lower-molar shearing crests, suggesting that this hominoid was very folivorous (Ungar and Kay 1995). Associated with variation in diet, there is great variation in the degree to which cranial features (e.g., zygomatic bone or supraorbital tori) are developed across the many taxa (Cameron 1997); however, Middle Miocene fossils tend to exhibit relatively thick molar enamel and relatively robust jaws (Andrews and Martin 1991).

In Spain, the cranium with upper dentition, part of a mandible, and partial skeleton of Pliobates (Family Pliobatidae), a small-bodied ape (4–5 kg; 9–11 lbs.), was discovered in deposits dating to 11.6 million years ago (Alba et al. 2015). It is believed to be a frugivore with a relative brain size that overlaps with modern cercopithecoids. The fossilized postcrania of Pliobates suggest that this ape might have had a unique style of locomotion, including the tendency to walk across the branches of trees with its palms facing downward and flexible wrists that permitted rotation of the forearm during climbing. However, the anatomy of the distal humerus differs from those of living apes in ways that suggest that Pliobates was less efficient at stabilizing its elbow while suspended (Benefit and McCrossin 2015). Two other recently described apes from Spain, Pierolapithecus and Anoiapithecus, are known from relatively complete skeletons. Pierolapithecus had a very projecting face and thick molar enamel as well as some skeletal features that suggest (albeit controversially) a less suspensory locomotor style than in extant apes (Moyà-Solà et al. 2004). In contrast to Pierolapithecus, the slightly younger Anoiapithecus has a very flat face (Moyà-Solà et al. 2009).

Postcranial evidence for suspensory or well-developed orthograde behaviors in apes does not appear until the Late Miocene of Europe. Primary evidence supporting these specialized locomotor modes includes the relatively short lumbar vertebrae of Oreopithecus (Figure 8.26) and Dryopithecus (Maclatchy 2004). Further, fossil material of the lower torso of O. bambolii (which dates to the Pan-hominin divergence) conveys a higher degree of flexion-extension abilities in the lumbar region (lower back) than what is possible in extant apes. Additionally, the hindlimb of O. bambolii is suggested to have supported powerful hip adduction during climbing (Hammond et al. 2020). The Late Miocene saw the extinction of most of the Eurasian hominoids in an event referred to as the Vallesian Crisis (Agustí et al. 2003). Among the latest surviving hominoid taxa in Eurasia were Oreopithecus and Gigantopithecus, the latter of which held out until the Pleistocene in Asia and was probably even sympatric with Homo erectus (Cachel 2015).

The Origins of Extant Apes

The fossil record of the extant apes is somewhat underwhelming: it ranges from being practically nonexistent for some taxa (e.g., chimpanzees) to being a little better for others (e.g., humans). There are many possible reasons for these differences in fossil abundance, and many are associated with the environmental conditions necessary for the fossilization of bones. One way to understand the evolution of extant apes that is not so dependent on the fossil record is via molecular evolutionary analyses. This can include counting up the differences in the genetic sequence between two closely related species to estimate the amount of time since these species shared a common ancestor. This is called a molecular clock, and it is often calibrated using fossils of known absolute age that stand in for the last common ancestor of a particular clade. Molecular clock estimates have placed the Hylobatidae and Hominidae split between 19.7 million and 24.1 million years ago, the African ape and Asian ape split between 15.7 million and 19.3 million years ago, and the split of Hylobatidae into its current genera between 6.4 million and 8 million years ago (Israfil et al. 2011).

Small Ape Origins and Fossils

Unfortunately, the fossil record for the small (formerly “lesser”) apes is meager, particularly in Miocene deposits. One possible early hylobatid is Laccopithecus robustus, a Late Miocene catarrhine from China (Harrison 2016). Although it does share some characteristics with modern gibbons and siamangs (including an overall small body size and a short face), Laccopithecus most likely represents a plesiomorphic stem catarrhine and is therefore distantly related to extant apes (Jablonski and Chaplin 2009). A more likely candidate for the hylobatid stem is another Late Miocene taxon from China, Yuanmoupithecus xiaoyuan. Interpretation of its phylogenetic standing, however, is complicated by contradicting dental features—some of them quite plesiomorphic—which some believe best place Yuanmoupithecus as a stem hylobatid (Harrison 2016). Recently, a Middle Miocene Indian fossil ape, Kapi ramnagarensis, has extended the fossil record of small apes by approximately five million years. Its teeth are suggestive of a shift to a more frugivorous diet and it is likely a stem hylobatid (Gilbert et al. 2020). The history of Hylobatidae becomes clearer in the Pleistocene, with fossils representing extant genera.

Great Ape Origins and Fossils

The most extensive fossil record of a modern great ape is that of our own genus, Homo. The evolution of our own species will be covered in Chapter 9. The evolutionary history of the Asian great ape, the orangutan (Pongo), is becoming clearer. Today, orangutans are found only on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. However, Pleistocene-aged teeth, attributed to Pongo, have been found in Cambodia, China, Laos, Peninsular Malaysia, and Vietnam—demonstrating the vastness of the orangutan’s previous range (Ibrahim et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2014). Sivapithecus from the Miocene of India and Pakistan is represented by many specimens, including parts of the face. Sivapithecus is very similar to Pongo, especially in the face, and it probably is closely related to ancestral orangutans (Pilbeam 1982). Originally, jaws and teeth belonging to the former genus Ramapithecus were thought to be important in the origin of humans (Simons 1961), but now these are recognized as specimens of Sivapithecus (Kelley 2002). Postcranial bones of Sivapithecus, however, suggest a more generalized locomotor mode—including terrestrial locomotion—than seen in Pongo (Pilbeam et al. 1990). Stable carbon and oxygen isotope data from dental enamel have reconstructed the paleoecological space of Sivapithecus (as well as the contemporaneous Late Miocene pongine Khoratpithecus) within the canopies of forested habitats (Habinger et al. 2022).

A probable close relative of Sivapithecus is the amazing Gigantopithecus (see Figure 8.24). Known only from teeth and jaws from China and India (e.g., Figure 8.27), this ape probably weighed as much as 270 kg (595 lbs.) and was likely the largest primate ever (Bocherens et al. 2017). Because of unique features of its teeth (including molarized premolars and patterns of wear) and its massive size, it has been reconstructed as a bamboo specialist, somewhat like the modern panda. Small silica particles (phytoliths) from grasses have been found stuck to the molars of Gigantopithecus (Ciochon et al. 1990). Recent studies evaluating the carbon isotope composition of the enamel sampled from Gigantopithecus teeth suggest that this ape exploited a wide range of vegetation, including fruits, leaves, roots, and bamboo (Bocherens et al. 2017). Its face is reminiscent of that of modern orangutans and it might belong in the same family, Pongidae (Kelley 2002).

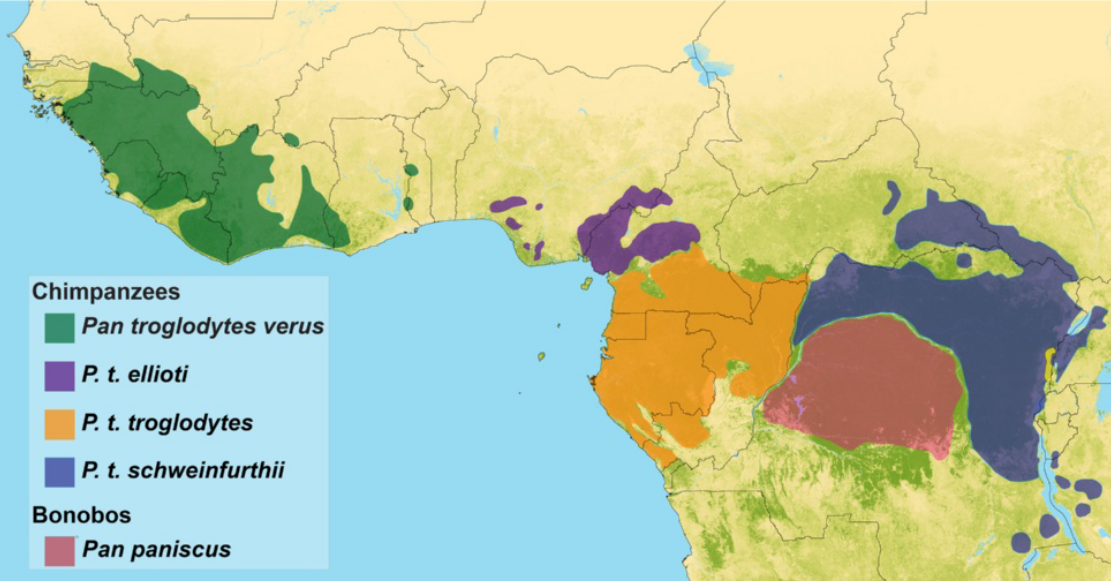

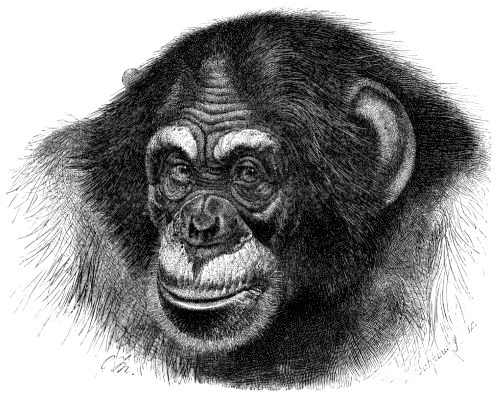

In Africa, the first fossil to be confidently attributed to Pan, and known to be the earliest evidence of a chimpanzee, was described based on teeth found in Middle Pleistocene deposits in the Eastern Rift Valley of Kenya (McBrearty and Jablonski 2005). Paleoenvironmental reconstructions of this locality suggest that this early chimpanzee was living in close proximity to early Homo in a closed-canopy wooded habitat. Similarly, fossil teeth and mandibular remains attributed to two species of Middle-Late Miocene apes—Chororapithecus abyssinicus (from Ethiopia; Suwa et al. 2007) and Nakalipithecus nakayamai (from Kenya; Kunimatsu et al. 2007)—have been suggested as basal members of the gorilla clade.

While the deposits of Eastern Africa have yielded a profound record of our fossil hominin ancestors, the continent’s rainforests remain a “palaeontological desert” (Rosas et al. 2022). Clearly, more work is needed to fill in the large gaps in the fossil record of the nonhuman great apes. The twentieth century witnessed the discovery of many hominin fossils in East Africa, which have been critical for improving our understanding of human evolution. While twenty-first-century conservationists fight to prevent the extinction of the living great apes, perhaps efforts by twenty-first-century paleoanthropologists will yield the evolutionary story of these, our closest relatives.

Review Questions

- Compare three major hypotheses about primate origins, making reference to each one’s key ecological reason for primate uniqueness.

- Explain how changes in temperature, rainfall, and vegetation led to major changes in primate biogeography over the Early Tertiary.

- List some euprimate features that plesiadapiforms have and some that they lack.

- Contrast adapoids and omomyoids in terms of life habits.

- Describe one piece of evidence for each of the adapoid, omomyoid, and tarsier origin hypotheses for anthropoids.

- Discuss the biogeography of the origins of African great apes and orangutans using examples from the Miocene ape fossil record.

Key Terms

Adapoidea: Order: Primates. One of the earliest groups of euprimates (true primates; earliest records from the early Eocene).

Adaptive radiations: Rapid diversifications of single lineages into many species which may present unique morphological features in response to different ecological settings.

Ancestral traits: Features that were inherited from a common ancestor and which remain (largely) unchanged.

Anthropoids:Group containing monkeys and apes, including humans.

Auditory bulla: The rounded bony floor of the middle ear cavity.

Bilophodonty: Dental condition in which the cusps of molar teeth form ridges (or lophs) separated from each other by valleys (seen, e.g., in modern catarrhine monkeys).

Catarrhines: Order: Primates; Suborder: Anthropoidea; Infraorder: Catarrhini. Group, with origins in Africa and Asia, that contains monkeys and apes, including humans.

Clade:Group containing all of the descendants of a single ancestor. A portion of a phylogenetic tree represented as a bifurcation (node) in a lineage and all of the branches leading forward in time from that bifurcation.

Convergent evolution: The independent evolution of a morphological feature in animals not closely related (e.g., wings in birds and bats).

Crown: Smallest monophyletic group (clade) containing a specified set of extant taxa and all descendants of their last common ancestor.

Diastema: Space between adjacent teeth.

Diffuse coevolution: The ecological interaction between whole groups of species (e.g., primates) with whole groups of other species (e.g., fruiting trees).

Ectotympanic: Bony ring or tube that holds the tympanic membrane (eardrum).

Euprimates: Order: Primates. True primates or primates of modern aspect.

Haplorhines: Group containing catarrhines, platyrrhines, and tarsiers.

Hominins: Modern humans and any extinct relatives more closely related to us than to chimpanzees.

Mandibular symphysis: Fibrocartilaginous joint between the left and right mandibular segments, located in the midline of the body.

Omomyoidea: Order: Primates; Superfamily: Omomyoidea. One of the earliest groups of euprimates (true primates; earliest record in the early Eocene).

Petrosal bone: The portion of the temporal bone that houses the inner ear apparatus.

Plagiaulacoid: Dental condition where at least one of the lower cheek-teeth (molars or premolars) is a laterally compressed blade.

Platyrrhines: Order: Primates; Suborder: Anthropoidea; Infraorder: Platyrrhini. Group containing monkeys found in the Americas.

Plesiadapiforms: Order: Plesiadapiformes. Archaic primates or primate-like placental mammals (Early Paleocene–Late Eocene).

Plesiomorphic: Having features that are shared by different groups which arose from a common ancestor.

Stem: Taxa that are basal to a given crown group but are more closely related to the crown group than to the closest living sister taxon of the crown group.

Strepsirrhines: Order: Primates; Suborder: Stresirrhini. Group containing lemurs, lorises, and galagos (does not include tarsiers).

Toothcomb: Dental condition found in modern strepsirrhines in which the lower incisors and canines are laterally compressed and protrude forward at a nearly horizontal inclination. This structure is used in grooming.

About the Authors

Jonathan M. G. Perry, Ph.D.

Western University of Health Sciences, Oregon, jperry@westernu.edu

Jonathan Perry was trained as a paleontologist and primatologist at the University of Alberta, Duke University, and Stony Brook University. His research focuses on the relationship between food, feeding, and craniodental anatomy in primates both living and extinct. This work includes primate feeding behavior, comparative anatomy, biomechanics, and field paleontology. He has taught courses on primate evolution at the undergraduate and graduate level.

Stephanie L. Canington, B.A., Ph.D.

University of Pennsylvania, scaning@upenn.edu

Stephanie Canington is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pennsylvania. Her current research is on the links between food properties, feeding behavior, and jaw morphology in lemurs that live in varying forms of captivity.

For Further Exploration

Beard, Chris. 2004. The Hunt for the Dawn Monkey: Unearthing the Origins of Monkeys, Apes, and Humans. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Begun, David R. 2010. “Miocene Hominids and the Origins of the African Apes and Humans.” Annual Review of Anthropology 39: 67–84.

Fleagle, John G. 2013. Primate Adaptation and Evolution. Third edition. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Gebo, Daniel L., ed. 1993. Postcranial Adaptations in Nonhuman Primates. Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

Godfrey, Laurie R., and William L. Jungers. 2002. “Quaternary Fossil Lemurs.” In The Primate Fossil Record, edited by Walter C. Hartwig, 97–121. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Godinot, Marc. 2006. “Lemuriform Origins as Viewed from the Fossil Record.” Folia Primatologica 77 (6): 446–464.

Kay, Richard F. 2018. “100 Years of Primate Paleontology.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 165 (4): 652–676.

Marivaux, Laurent. 2006. “The Eosimiid and Amphipithecid Primates (Anthropoidea) from the Oligocene of the Bugti Hills (Balochistan, Pakistan): New Insight into Early Higher Primate Evolution in South Asia.” Palaeovertebrata, Montpellier 34 (1–2): 29–109.

Martin, R. D. 1990. Primate Origins and Evolution: A Phylogenetic Reconstruction. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rose, Kenneth D., Marc Godinot, and Thomas M. Bown. 1994. “The Early Radiation of Euprimates and the Initial Diversification of Omomyidae.” In Anthropoid Origins: The Fossil Evidence, edited by John G. Fleagle and Richard F. Kay, 1–28. New York: Plenum Press.

Ross, Callum F. 1999. “How to Carry Out Functional Morphology.” Evolutionary Anthropology 7 (6): 217–222.

Seiffert, Erik R. 2012. “Early Primate Evolution in Afro-Arabia.” Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 21(6): 239–253.

Szalay, Frederic S., and Eric Delson. 1979. Evolutionary History of the Primates. New York: Academic Press.

Ungar, Peter S. 2002. “Reconstructing the Diets of Fossil Primates.” In Reconstructing Behavior in the Primate Fossil Record, edited by Joseph Plavcan, Richard F. Kay, William Jungers, and Carel P. van Schaik, 261–296. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

References

Agustí, J., A. Sanz de Siria, and M. Garcés M. 2003. “Explaining the End of the Hominoid Experiment in Europe.” Journal of Human Evolution 45 (2): 145–153.

Alba, David M., Sergio Almécija, Daniel DeMiguel, Josep Fortuny, Miriam Pérez de los Ríos, Marta Pina, Josep M. Robles, and Salvador Moyà-Solà. 2015. “Miocene Small-Bodied Ape from Eurasia Sheds Light on Hominoid Evolution.” Science 350 (6260): aab2625.

Andrews, Peter, and Lawrence Martin. 1991. “Hominoid Dietary Evolution.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 334 (1270): 199–209.

Antoine, Pierre-Oliver, Laurent Marivaux, Darren A. Croft, Guillaume Billet, Morgan Ganerød, Carlos Jaramillo, Thomas Martin, et al. 2012. “Middle Eocene Rodents from Peruvian Amazonia Reveal the Pattern and Timing of Caviomorph Origins and Biogeography.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 279 (1732): 1319–1326.

Beard, K. Christopher. 1990. “Gliding Behaviour and Palaeoecology of the Alleged Primate Family Paromomyidae (Mammalia, Dermoptera).” Nature 345 (6273): 340–341.

Beard, K. Christopher. 2002. “Basal Anthropoids.” In The Primate Fossil Record, edited by William C. Hartwig, 133–150. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beard, K. Christopher, and R. D. E. MacPhee. 1994. “Cranial Anatomy of Shoshonius and the Antiquity of Anthropoidea.” In Anthropoid Origins: The Fossil Evidence, edited by John G. Fleagle and Richard F. Kay, 55–98. New York: Plenum Press.

Beard, K. Christopher, Laurent Marivaux, Soe Thura Tun, Aung Naing Soe, Yaowalak Chaimanee, Wanna Htoon, Bernard Marandat, Htun Htun Aung, and Jean-Jacques Jaeger. 2007. “New Sivaladapid Primates from the Eocene Pondaung Formation of Myanmar and the Anthropoid Status of Amphipithecidae.” Bulletin of Carnegie Museum of Natural History 39: 67–76.

Beard, K. Christopher, Tao Qi, Mary R. Dawson, Banyue Wang, and Chuankuei Li. 1994. “A Diverse New Primate Fauna from Middle Eocene Fissure-Fillings in Southeastern China.” Nature 368 (6472): 604–609.

Beard, K. Christopher, Yongsheng Tong, Mary R. Dawson, Jingwen Wang, and Xueshi Huang. 1996. “Earliest Complete Dentition of an Anthropoid Primate from the Late Middle Eocene of Shanxi Province, China.” Science 272 (5258): 82–85.