4 Forces of Evolution

Beth Shook; Ph.D.; Lara Braff; Katie Nelson; Kelsie Aguilera; and M.A.

Andrea J. Alveshere, Ph.D., Western Illinois University

This chapter is a revision from “Chapter 4: Forces of Evolution” by Andrea J. Alveshere. In Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology, first edition, edited by Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera, and Lara Braff, which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Learning Objectives

- Outline a 21st-century perspective of the Modern Synthesis.

- Define populations and population genetics as well as the methods used to study them.

- Identify the forces of evolution and become familiar with examples of each.

- Discuss the evolutionary significance of mutation, genetic drift, gene flow, and natural selection.

- Explain how allele frequencies can be used to study evolution as it happens.

- Contrast micro- and macroevolution.

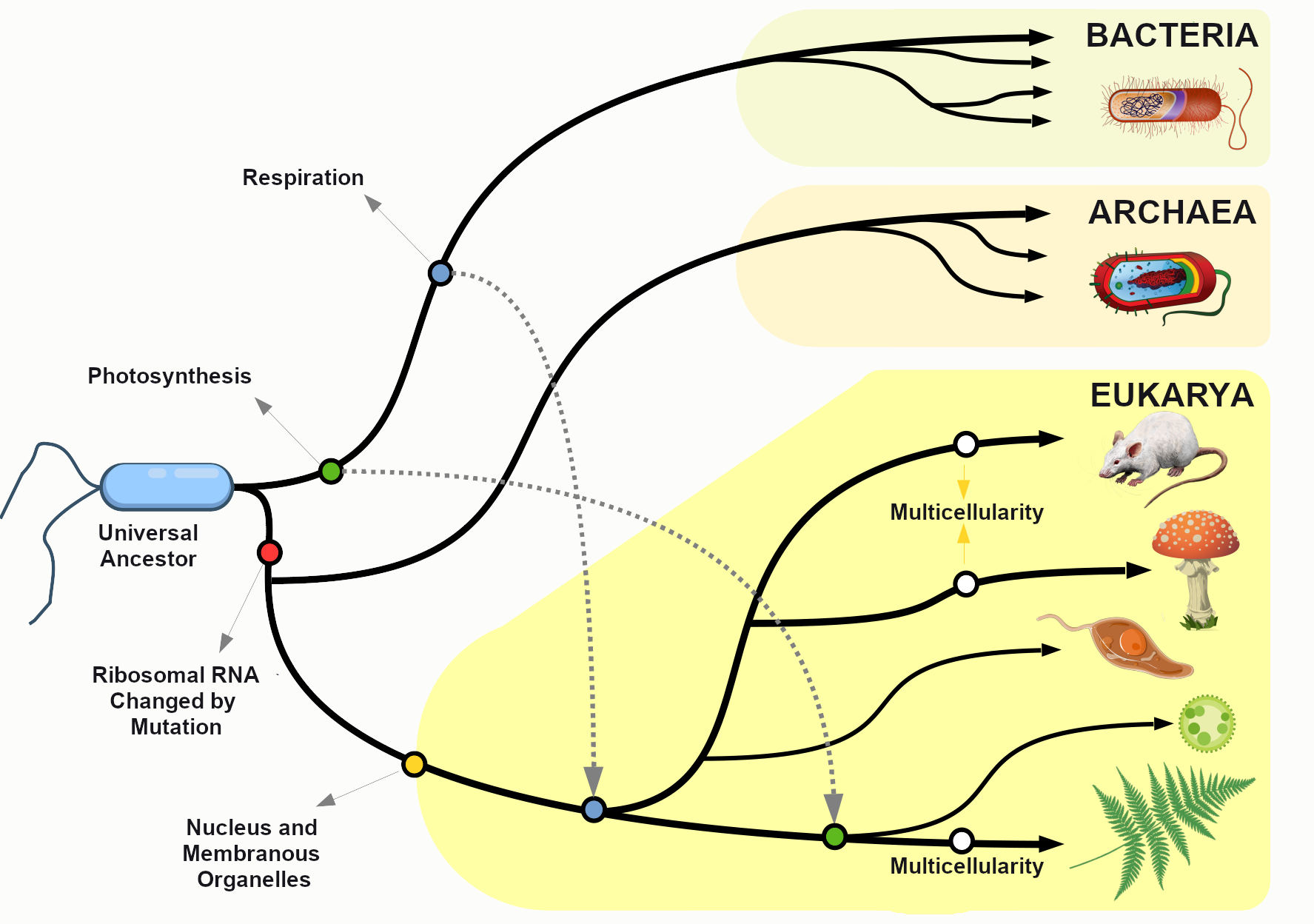

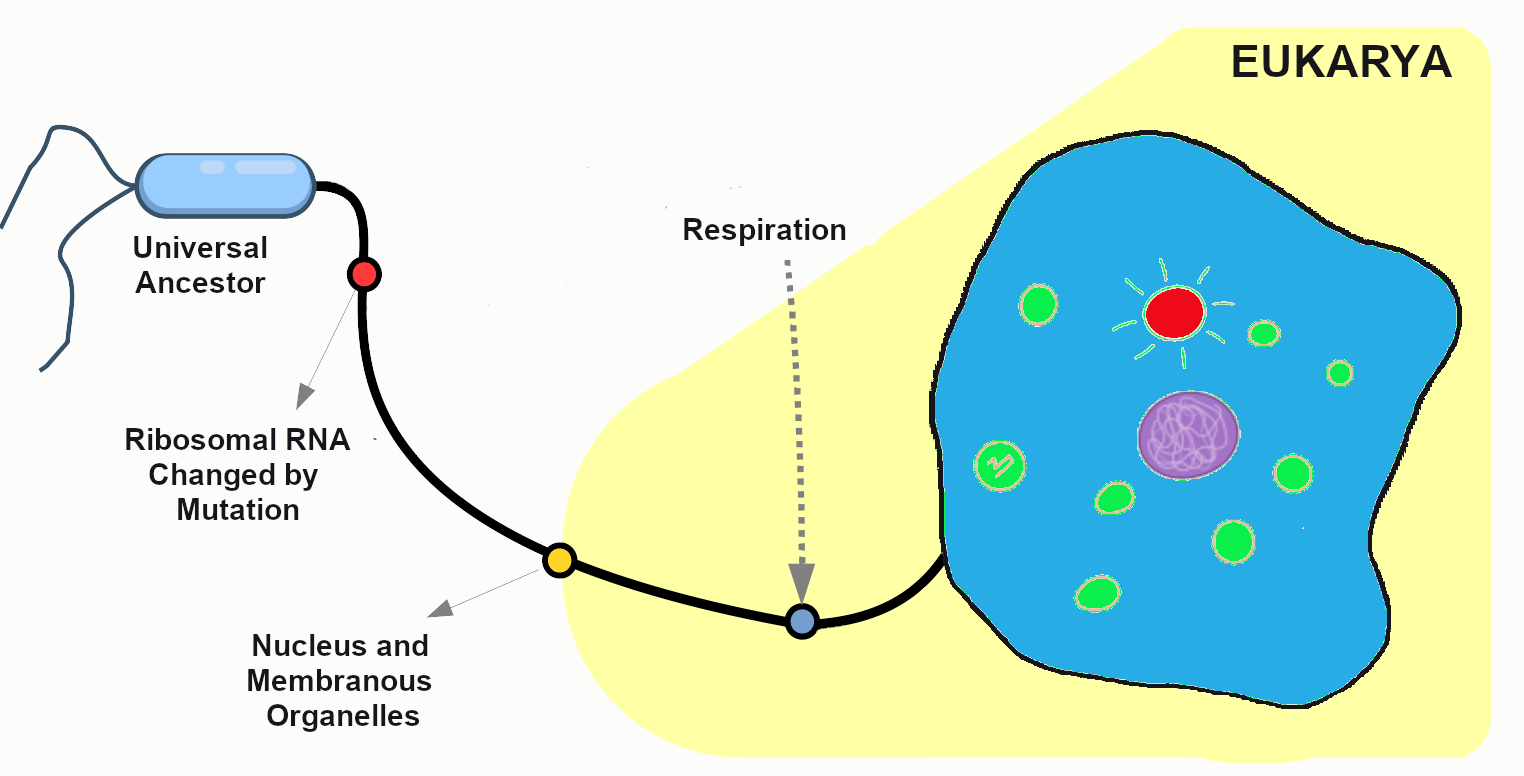

It’s hard for us, with our typical human life spans of less than 100 years, to imagine all the way back, 3.8 billion years ago, to the origins of life. Scientists still study and debate how life came into being and whether it originated on Earth or in some other region of the universe (including some scientists who believe that studying evolution can reveal the complex processes that were set in motion by God or a higher power). What we do know is that a living single-celled organism was present on Earth during the early stages of our planet’s existence. This organism had the potential to reproduce by making copies of itself, just like bacteria, many amoebae, and our own living cells today. In fact, with modern technologies, we can now trace genetic lineages, or phylogenies, and determine the relationships between all of today’s living organisms—eukaryotes (animals, plants, fungi, etc.), archaea, and bacteria—on the branches of the phylogenetic tree of life (Figure 4.1).

Looking at the common sequences in modern genomes, we can even make educated guesses about the likely genetic sequence of the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) of all living things. Through a wondrous series of mechanisms and events over nearly four billion years, that ancient single-celled organism gave rise to the rich diversity of species that fill the lands, seas, and skies of our planet. This chapter explores the mechanisms by which that amazing transformation occurred and considers some of the crucial scientific experiments that shaped our current understanding of the evolutionary process.

Updating the Modern Synthesis: Tying it All Together

Chapter 2 examined the roles played by many different scientists, and their many careful scientific experiments, in providing the full picture of evolution. The term Modern Synthesis describes the integration of these various lines of evidence into a unified theory of evolution.

While the biggest leap forward in understanding how evolution works came with the joining (synthesis) of Darwin’s concept of natural selection with Mendel’s insights about particulate inheritance (described in detail in Chapter 3), there were some other big contributions that were crucial to making sense of the variation that was being observed. Mathematical models for evolutionary change provided the tools to study variation and became the basis for the study of population genetics (Fisher 1919; Haldane 1924). Other experiments revealed the existence of chromosomes as carriers of collections of genes (Dobzhansky 1937; Wright 1932).

Studies on wild butterflies confirmed the mathematical predictions and also led to the definition of the concept of polymorphisms to describe multiple forms of a trait (Ford 1949). These studies led to many useful advances such as the discovery that human blood type polymorphisms are maintained in the human population because they are involved in disease resistance (Ford 1942; see also the Special Topic box on Sickle Cell Anemia below).

Population Genetics

Defining Populations and the Variations within Them

One of the major breakthroughs in understanding the mechanisms of evolutionary change came with the realization that evolution takes place at the level of populations, not within individuals. In the biological sciences, a population is defined as a group of individuals of the same species who are geographically near enough to one another that they can breed and produce new generations of individuals.

For the purpose of studying evolution, we recognize populations by their even smaller units: genes. Remember, a gene is the basic unit of information that encodes the proteins needed to grow and function as a living organism. Each gene can have multiple alleles, or variants—each of which may produce a slightly different protein. Each individual, for genetic inheritance purposes, carries a collection of genes that can be passed down to future generations. For this reason, in population genetics, we think of populations as gene pools, which refers to the entire collection of genetic material in a breeding community that can be passed on from one generation to the next.

For genes carried on our human chromosomes (our nuclear DNA), we inherit two copies of each, one from each parent. This means we may carry two of the same alleles (a homozygous genotype) or two different alleles (a heterozygous genotype) for each nuclear gene.

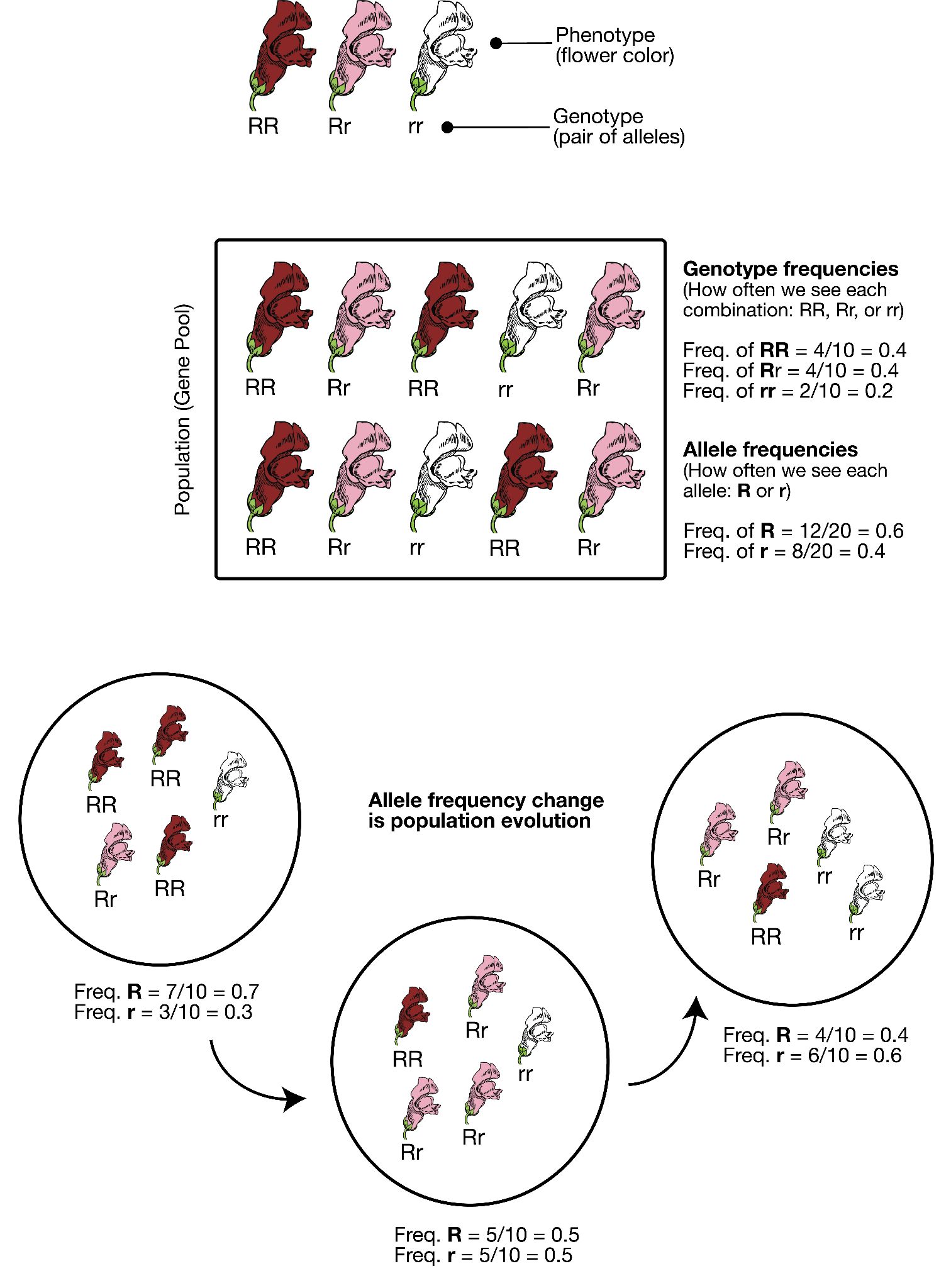

Defining Evolution

In order to understand evolution, it’s crucial to remember that evolution is always studied at the population level. Also, if a population were to stay exactly the same from one generation to the next, it would not be evolving. So evolution requires both a population of breeding individuals and some kind of a genetic change occurring within it. Thus, the simple definition of evolution is a change in the allele frequencies in a population over time. What do we mean by allele frequencies? Allele frequencies refer to the ratio, or percentage, of one allele (one variant of a gene) compared to the other alleles for that gene within the study population (Figure 4.2). By contrast, genotype frequencies are the ratios or percentages of the different homozygous and heterozygous genotypes in the population. Because we carry two alleles per genotype, the total count of alleles in a population will usually be exactly double the total count of genotypes in the same population (with the exception being rare cases in which an individual carries a different number of chromosomes than the typical two; e.g., Down syndrome results when a child carries three copies of Chromosome 21).

The Forces of Evolution

Today, we recognize that evolution takes place through a combination of mechanisms: mutation, genetic drift, gene flow, and natural selection. These mechanisms are called the “forces of evolution”; together they account for all the genotypic variation observed in the world today. Keep in mind that each of these forces was first defined and then tested—and retested—through the experimental work of the many scientists who contributed to the Modern Synthesis.

Mutation

The first force of evolution we will discuss is mutation, and for good reason: mutation is the original source of all the genetic variation found in every living thing. Imagine all the way back in time to the very first single-celled organism, floating in Earth’s primordial sea. Based on what we observe in simple, single-celled organisms today, that organism probably spent its lifetime absorbing nutrients and dividing to produce cloned copies of itself. While the numbers of individuals in that population would have grown (as long as the environment was favorable), nothing would have changed in that perfectly cloned population. There would not have been variety among the individuals. It was only through a copying error—the introduction of a mutation, or change, into the genetic code—that new alleles were introduced into the population.

After many generations have passed in our primordial population, mutations have created distinct chromosomes. The cells are now amoeba-like, larger than many of their tiny bacterial neighbors, who have long since become their favorite source of nutrients. Without mutation to create this diversity, all living things would still be identical to LUCA, our universal ancestor (Figure 4.3).

When we think of genetic mutation, we often first think of deleterious mutations—the ones associated with negative effects such as the beginnings of cancers or heritable disorders. The fact is, though, that every genetic adaptation that has helped our ancestors survive since the dawn of life is directly due to beneficial mutations—changes in the DNA that provided some sort of advantage to a given population at a particular moment in time. For example, a beneficial mutation allowed chihuahuas and other tropical-adapted dog breeds to have much thinner fur coats than their cold-adapted cousins the northern wolves, malamutes, and huskies.

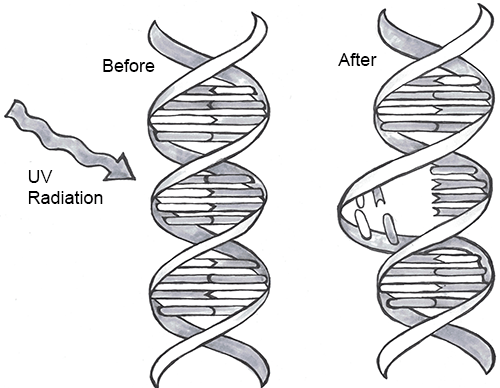

Every one of us has genetic mutations. Yes, even you. The DNA in some of your cells today differs from the original DNA that you inherited when you were a tiny, fertilized egg. Mutations occur all the time in the cells of our skin and other organs, due to chemical changes in the nucleotides. Exposure to the UV radiation in sunlight is one common cause of skin mutations. Interaction with UV light causes UV crosslinking, in which adjacent thymine bases bind with one another (Figure 4.4). Many of these mutations are detected and corrected by DNA repair mechanisms, enzymes that patrol and repair DNA in living cells, while other mutations may cause a new freckle or mole or, perhaps, an unusual hair to grow. For people with the autosomal recessive disease xeroderma pigmentosum, these repair mechanisms do not function correctly, resulting in a host of problems especially related to sun exposure, including severe sunburns, dry skin, heavy freckling, and other pigment changes.

Most of our mutations exist in somatic cells, which are the cells of our organs and other body tissues. Those will not be passed onto future generations and so will not affect the population over time. Only mutations that occur in the gametes, the reproductive cells (i.e., the sperm or egg cells), will be passed onto future generations. When a new mutation pops up at random in a family lineage, it is known as a spontaneous mutation. If the individual born with this spontaneous mutation passes it on to his offspring, those offspring receive an inherited mutation. Geneticists have identified many classes of mutations and the causes and effects of many of these.

Point Mutations

A point mutation is a single-letter (single-nucleotide) change in the genetic code resulting in the substitution of one nucleic acid base for a different one. As you learned in Chapter 3, the DNA code in each gene is translated through three-letter “words” known as codons. So depending on how the point mutation changes the “word,” the effect it will have on the protein may be major or minor or may make no difference at all.

If a mutation does not change the resulting protein, then it is called a synonymous mutation. Synonymous mutations do involve a letter (nucleic acid) change, but that change results in a codon that codes for the same “instruction” (the same amino acid or stop code) as the original codon. Mutations that do cause a change in the protein are known as nonsynonymous mutations. Nonsynonymous mutations may change the resulting protein’s amino acid sequence by altering the DNA sequence that encodes the mRNA or by changing how the mRNA is spliced prior to translation (refer to Chapter 3 for more details).

Insertions and Deletions

In addition to point mutations, another class of mutations are insertions and deletions, or indels, for short. As the name suggests, these involve the addition (insertion) or removal (deletion) of one or more coding sequence letters (nucleic acids). These typically first occur as an error in DNA replication, wherein one or more nucleotides are either duplicated or skipped in error. Entire codons or sets of codons may also be removed or added if the indel is a multiple of three nucleotides.

Frameshift mutations are types of indels that involve the insertion or deletion of any number of nucleotides that is not a multiple of three (e.g., adding one or two extra letters to the code). Because these indels are not consistent with the codon numbering, they “shift the reading frame,” causing all the codons beyond the mutation to be misread. Like point mutations, small indels can also disrupt splice sites.

Transposable elements, or transposons, are fragments of DNA that can “jump” around in the genome. There are two types of transposons: retrotransposons are transcribed from DNA into RNA and then “reverse transcribed,” to insert the copied sequence into a new location in the DNA, and DNA transposons, which do not involve RNA. DNA transposons are clipped out of the DNA sequence itself and inserted elsewhere in the genome. Because transposable elements insert themselves into existing DNA sequences, they are frequent gene disruptors. At certain times, and in certain species, it appears that transposons became very active, likely accelerating the mutation rate (and thus, the genetic variation) in those populations during the active periods.

Chromosomal Alterations

The final major category of genetic mutations are changes at the chromosome level: crossover events, nondisjunction events, and translocations. Crossover events occur when DNA is swapped between homologous chromosomes while they are paired up during meiosis I. Crossovers are thought to be so common that some DNA swapping may happen every time chromosomes go through meiosis I. Crossovers don’t necessarily introduce new alleles into a population, but they do make it possible for new combinations of alleles to exist on a single chromosome that can be passed to future generations. This also enables new combinations of alleles to be found within siblings who share the same parents. Also, if the fragments that cross over don’t break at exactly the same point, they can cause genes to be deleted from one of the homologous chromosomes and duplicated on the other.

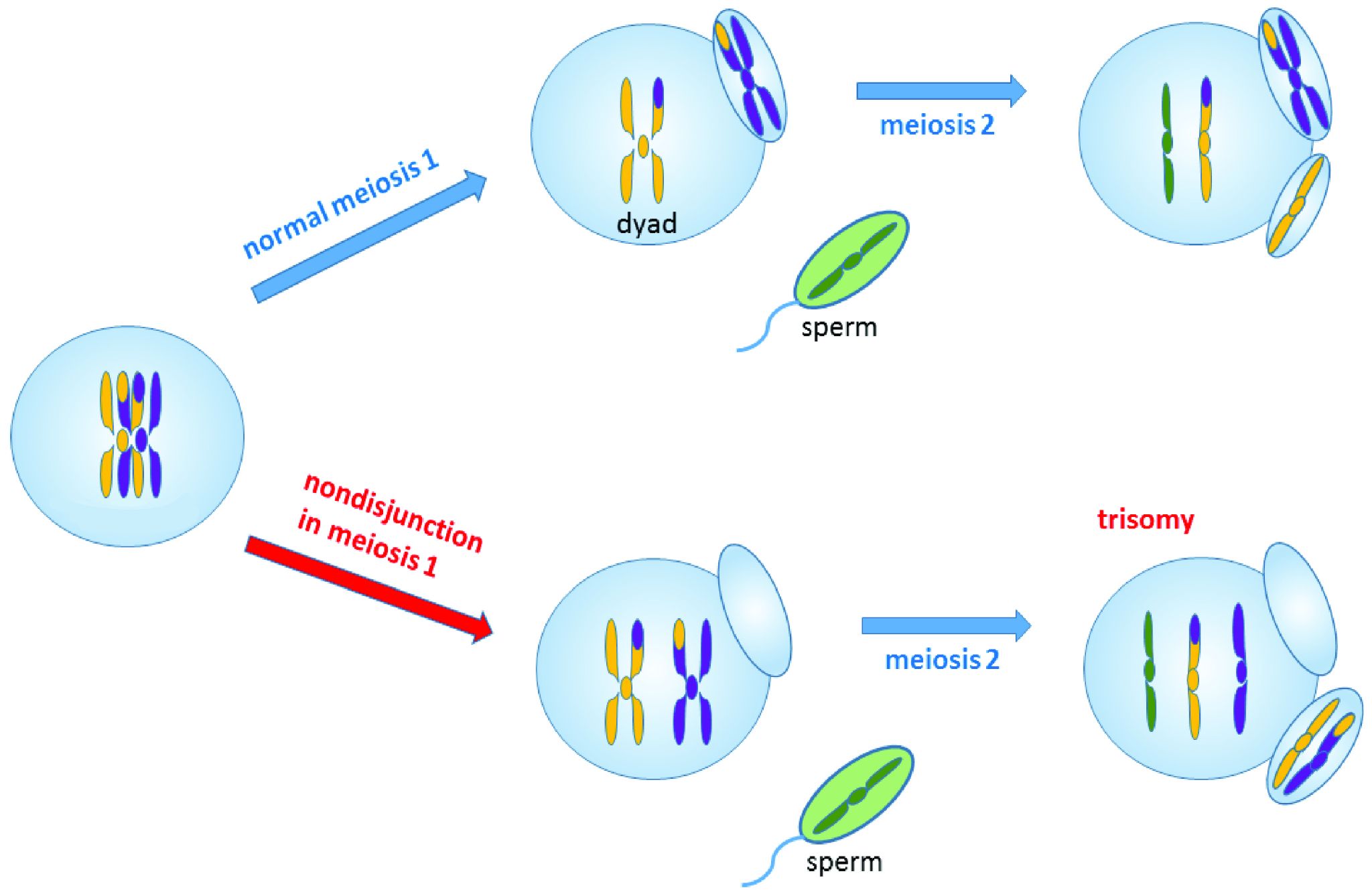

Nondisjunction events occur when the homologous chromosomes (in meiosis I) or sister chromatids (in meiosis II and mitosis) fail to separate after pairing. The result is that both chromosomes or chromatids end up in the same daughter cell, leaving the other daughter cell without any copy of that chromosome (Figure 4.5). Most nondisjunctions at the gamete level are fatal to the embryo. The most widely known exception is Trisomy 21, or Down syndrome, which results when an embryo inherits three copies of Chromosome 21: two from one parent (due to a nondisjunction event) and one from the other (Figure 4.6). Trisomies (triple chromosome conditions) of Chromosomes 18 (Edwards syndrome) and 13 (Patau syndrome) are also known to result in live births, but the children usually have severe complications and rarely survive beyond the first year of life.

Sex chromosome trisomies (XXX, XXY, XYY) and X chromosome monosomies (inheritance of an X chromosome from one parent and no sex chromosome from the other) are also survivable and fairly common. The symptoms vary but often include atypical sexual characteristics, either at birth or at puberty, and often result in sterility. The X chromosome carries unique genes that are required for survival; therefore, Y chromosome monosomies are incompatible with life.

Chromosomal translocations involve transfers of DNA between nonhomologous chromosomes. This may involve swapping large portions of two or more chromosomes. The exchanges of DNA may be balanced or unbalanced. In balanced translocations, the genes are swapped, but no genetic information is lost. In unbalanced translocations, there is an unequal exchange of genetic material, resulting in duplication or loss of genes. Translocations result in new chromosomal structures called derivative chromosomes, because they are derived or created from two different chromosomes. Translocations are often found to be linked to cancers and can also cause infertility. Even if the translocations are balanced in the parent, the embryo often won’t survive unless the baby inherits both of that parent’s derivative chromosomes (to maintain the balance).

Genetic Drift

The second force of evolution is commonly known as genetic drift. This is an unfortunate misnomer, as this force actually involves the drifting of alleles, not genes. Genetic drift refers to random changes (“drift”) in allele frequencies from one generation to the next. The genes are remaining constant within the population; it is only the alleles of the genes that are changing in frequency. The random nature of genetic drift is a crucial point to understand: it specifically occurs when none of the variant alleles confer an advantage.

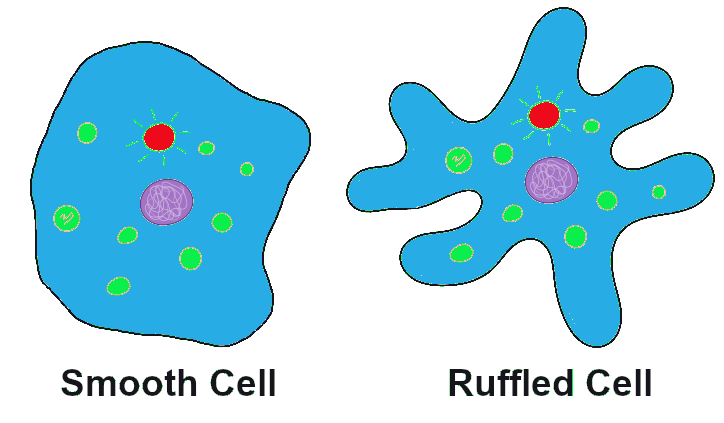

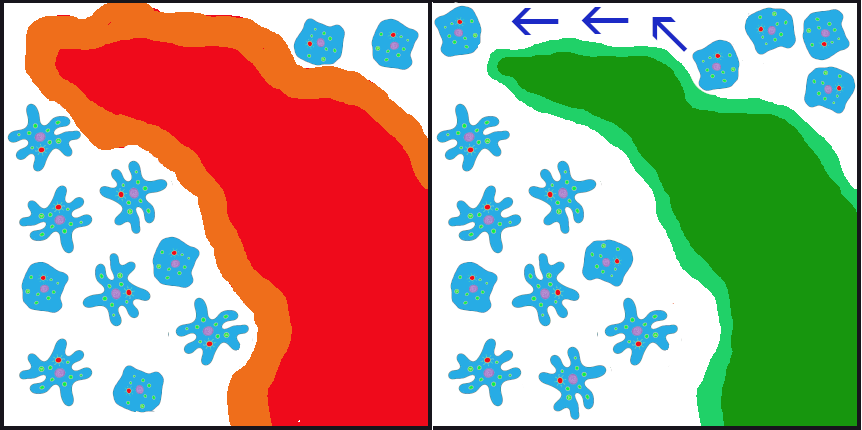

Let’s imagine far back in time, again, to that ancient population of amoeba-like cells, subsisting and occasionally dividing, in the primordial sea. A mutation occurs in one of the cells that changes the texture of the cell membrane from a relatively smooth surface to a highly ruffled one (Figure 4.7). This has absolutely no effect on the cell’s quality of life or ability to reproduce. In fact, eyes haven’t evolved yet, so no one in the world at the time would even notice the difference. The cells in the population continue to divide, and the offspring of the ruffled cell inherit the ruffled membrane. The frequency (percentage) of the ruffled allele in the population, from one generation to the next, will depend entirely on how many offspring that first ruffled cell ends up having, and the random events that might make the ruffled alleles more common or more rare (such as population bottlenecks and founder effects, which are discussed below).

Sexual Reproduction and Random Inheritance

Tracking alleles gets a bit more complicated in our primordial cells when, after a number of generations, a series of mutations have created populations that reproduce sexually. These cells now must go through an extra round of cell division (meiosis) to create haploid gametes. The combination of two gametes is now required to produce each new diploid offspring.

In the earlier population, which reproduced via asexual reproduction, a cell either carried the smooth allele or the ruffled allele. With sexual reproduction, a cell inherits one allele from each parent, so there are homozygous cells that contain two smooth alleles, homozygous cells that contain two ruffled alleles, and heterozygous cells that contain one of each allele (Figure 4.8). If the new, ruffled allele happens to be dominant (and we’ll imagine that it is), the heterozygotes will have ruffled cell phenotypes but also will have a 50/50 chance of passing on a smooth allele to each offspring. As long as neither phenotype (ruffled nor smooth) provides any advantage over the other, the variation in the population from one generation to the next will remain completely random.

In sexually reproducing populations (including humans and many other animals and plants in the world today), that 50/50 chance of inheriting one or the other allele from each parent plays a major role in the random nature of genetic drift.

Population Bottlenecks

A population bottleneck occurs when the number of individuals in a population drops dramatically due to some random event. The most obvious, familiar examples are natural disasters. Tsunamis and hurricanes devastating island and coastal populations and forest fires and river floods wiping out populations in other areas are all too familiar. When a large portion of a population is randomly wiped out, the allele frequencies (i.e., the percentages of each allele) in the small population of survivors are often much different from the frequencies in the predisaster, or “parent,” population.

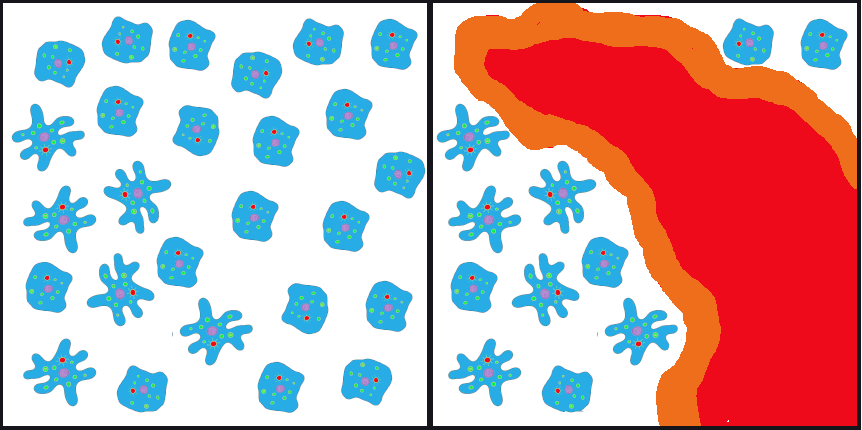

If such an event happened to our primordial ocean cell population—perhaps a volcanic fissure erupted in the ocean floor and only the cells that happened to be farthest from the spewing lava and boiling water survived—we might end up, by random chance, with a surviving population that had mostly ruffled alleles, in contrast to the parent population, which had only a small percentage of ruffles (Figure 4.9).

One of the most famous examples of a population bottleneck is the prehistoric disaster that led to the extinction of dinosaurs, the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (often abbreviated K–Pg; previously K-T). This occurred approximately 66 million years ago. Dinosaurs and all their neighbors were going about their ordinary routines when a massive asteroid zoomed in from space and crashed into what is now the Gulf of Mexico, creating an impact so enormous that populations within hundreds of miles of the crash site were likely immediately wiped out. The skies filled with dust and debris, causing temperatures to plummet worldwide. It’s estimated that 75% of the world’s species went extinct as a result of the impact and the deep freeze that followed (Jablonski and Chaloner 1994).

The populations that emerged from the K-Pg extinction were markedly different from their predisaster communities. Surviving mammal populations expanded and diversified, and other new creatures appeared. The ecosystems of Earth were filled with new organisms and have never been the same (Figure 4.10).

Much more recently in geological time, during the colonial period, many human populations experienced bottlenecks as a result of the fact that imperial powers were inclined to slaughter communities who were reluctant to give up their lands and resources. This effect was especially profound in the Americas, where Indigenous populations faced the compounded effects of brutal warfare, exposure to new bacteria and viruses (against which they had no immunity), and ultimately segregation on resource-starved reservations. The populations in Europe, Asia, and Africa had experienced regular gene flow during the 10,000-year period in which most kinds of livestock were being domesticated, giving them many generations of experience building up immunity against zoonotic diseases (those that can pass from animals to humans). In contrast, the residents of the Americas had been almost completely isolated during those millennia, so all these diseases swept through the Americas in rapid succession, creating a major loss of genetic diversity in the Indigenous American population. It is estimated that between 50% and 95% of the Indigenous American populations died during the first decades after European contact, around 500 years ago (Livi-Bacci 2006).

An urgent health challenge facing humans today involves human-induced population bottlenecks that produce antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Antibiotics are medicines prescribed to treat bacterial infections. The typical prescription includes enough medicine for ten days. People often feel better much sooner than ten days and sometimes decide to quit taking the medicine ahead of schedule. This is often a big mistake. The antibiotics have quickly killed off a large percentage of the bacteria—enough to reduce the symptoms and make you feel much better. However, this has created a bacterial population bottleneck. There are usually a small number of bacteria that survive those early days. If you take the medicine as prescribed for the full ten days, it’s quite likely that there will be no bacterial survivors. If you quit early, though, the survivors—who were the members of the original population who were most resistant to the antibiotic—will begin to reproduce again. Soon the infection will be back, possibly worse than before, and now all of the bacteria are resistant to the antibiotic that you had been prescribed.

Other activities that have contributed to the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria include the use of antibacterial cleaning products and the inappropriate use of antibiotics as a preventative measure in livestock or to treat infections that are viral instead of bacterial (viruses do not respond to antibiotics). In 2017, the World Health Organization published a list of twelve antibiotic-resistant pathogens that are considered top priority targets for the development of new antibiotics (World Health Organization 2017).

Founder Effects

Founder effects occur when members of a population leave the main or “parent” group and form a new population that no longer interbreeds with the other members of the original group. Similar to survivors of a population bottleneck, the newly founded population often has allele frequencies that are different from the original group. Alleles that may have been relatively rare in the parent population can end up being very common due to the founder effect. Likewise, recessive traits that were seldom seen in the parent population may be seen frequently in the descendants of the offshoot population.

One striking example of the founder effect was first noted in the Dominican Republic in the 1970s. During a several-year period, eighteen children who had been born with female genitalia and raised as girls suddenly grew penises at puberty. This culture tended to value sons over daughters, so these transitions were generally celebrated. They labeled the condition guevedoces, which translates to “penis at twelve,” due to the average age at which this occurred. Scientists were fascinated by the phenomenon.

Genetic and hormonal studies revealed that the condition, scientifically termed 5-alpha reductase deficiency, is an autosomal recessive syndrome that manifests when a child having both X and Y sex chromosomes inherits two nonfunctional (mutated) copies of the SRD5A2 gene (Imperato-McGinley and Zhu 2002). These children develop testes internally, but the 5-alpha reductase 2 steroid, which is necessary for development of male genitals in babies, is not produced. In absence of this male hormone, the baby develops female-looking genitalia (in humans, “female” is the default infant body form, if the full set of the necessary male hormones are not produced). At puberty, however, a different set of male hormones are produced by other fully functional genes. These hormones complete the male genital development that did not happen in infancy. This condition became quite common in the Dominican Republic during the 1970s due to founder effect—that is, the mutated SRD5A2 gene happened to be much more common among the Dominican Republic’s founding population than in the parent populations. (The Dominican population derives from a mixture of Indigenous Americans [Taino] peoples, West Africans, and Western Europeans.) Five-alpha reductase syndrome has since been observed in other small, isolated populations around the world.

Founder effect is closely linked to the concept of inbreeding, which in population genetics does not necessarily mean breeding with immediate family relatives. Instead, inbreeding refers to the selection of mates exclusively from within a small, closed population—that is, from a group with limited allelic variability. This can be observed in small, physically isolated populations but also can happen when cultural practices limit mates to a small group. As with the founder effect, inbreeding increases the risk of inheriting two copies of any nonfunctional (mutant) alleles.

The Amish in the United States are a population that, due to their unique history and cultural practices, emerged from a small founding population and have tended to select mates from within their groups. The Old Order Amish population of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, has approximately 50,000 current members, all of whom can trace their ancestry back to a group of approximately 80 individuals. This small founding population immigrated to the United States from Switzerland in the mid-1700s to escape religious persecution. Since the Amish keep to themselves and almost exclusively select mates from within their own communities, they have more recessive traits compared to their parent population.

One of the genetic conditions that has been observed much more frequently in the Lancaster County Amish population is Ellis-van Creveld syndrome, which is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by short stature (dwarfism), polydactyly (the development of more than five digits [fingers or toes] on the hands or feet], abnormal tooth development, and heart defects (Figure 4.11). Among the general world population, Ellis-van Creveld syndrome is estimated to affect approximately 1 in 60,000 individuals; among the Old Order Amish of Lancaster County, the rate is estimated to be as high as 1 in every 200 births (D’Asdia et al. 2013).

One important insight that has come from the study of founder effects is that a limited gene pool carries a much higher risk for genetic diseases. Genetic diversity in a population greatly reduces these risks.

Gene Flow

The third force of evolution is traditionally called gene flow. As with genetic drift, this is a misnomer, because it refers to flowing alleles, not genes. (All members of the same species share the same genes; it is the alleles of those genes that may vary.) Gene flow refers to the movement of alleles from one population to another. In most cases, gene flow can be considered synonymous with migration.

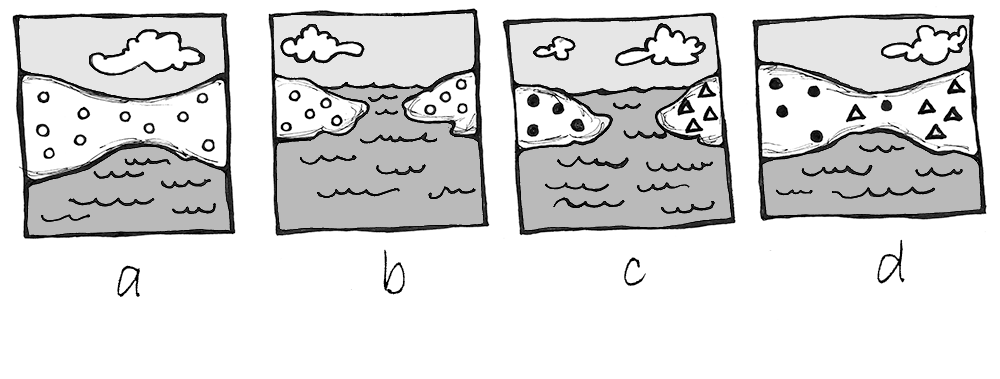

Returning again to the example of our primordial cell population, let’s imagine that, after the volcanic fissure opened up in the ocean floor, wiping out the majority of the parent population, two surviving populations developed in the waters on opposite sides of the fissure. Ultimately, the lava from the fissure cooled into a large island that continued to provide a physical barrier between the populations (Figure 4.12).

In the initial generations after the eruption, due to founder effect, isolation, and random inheritance (genetic drift), the population to the west of the islands contained a vast majority of the ruffled membrane alleles while the eastern population carried only the smooth alleles. Ocean currents in the area typically flowed from east to west, sometimes carrying cells (facilitating gene flow) from the eastern (smooth) population to the western (ruffled) population. Due to the ocean currents, it was almost impossible for any cells from the western population to be carried eastward. Thus, for inheritance purposes, the eastern (smooth) population remained isolated. In this case, the gene flow is unidirectional (going only in one direction) and unbalanced (only one population is receiving the new alleles).

Among humans, gene flow is often described as admixture. In forensic cases, anthropologists and geneticists are often asked to estimate the ancestry of unidentified human remains to help determine whether they match any missing persons’ reports. This is one of the most complicated tasks in these professions because, while “race” or “ancestry” involves simple checkboxes on a missing person’s form, among humans today there are no truly distinct genetic populations. All modern humans are members of the same fully breeding compatible species, and all human communities have experienced multiple episodes of gene flow (admixture), leading all humans today to be so genetically similar that we are all members of the same (and only surviving) human subspecies: Homo sapiens sapiens.

Gene flow between otherwise isolated nonhuman populations is often termed hybridization.. One example of this involves the hybridization and spread of Scutellata honey bees (a.k.a. “killer bees”) in the Americas. All honey bees worldwide are classified as Apis mellifera. Due to distinct adaptations to various environments around the world, there are 28 different subspecies of Apis mellifera.

During the 1950s, a Brazilian biologist named Warwick E. Kerr experimented with hybridizing African and European subspecies of honey bees to try to develop a strain that was better suited to tropical environments than the European honey bees that had long been kept by North American beekeepers. Dr. Kerr was careful to contain the reproductive queens and drones from the African subspecies, but in 1957, a visiting beekeeper accidentally released 26 queen bees of the Scutellata subspecies (Apis mellifera scutellata) from southern Africa into the Brazilian countryside. The Scutellata bees quickly interbred with local European honey bee populations. The hybridized bees exhibited a much more aggressively defensive behavior, fatally or near-fatally attacking many humans and livestock that ventured too close to their hives. The hybridized bees spread throughout South America and reached Mexico and California by 1985. By 1990, permanent colonies had been established in Texas, and by 1997, 90% of trapped bee swarms around Tucson, Arizona, were found to be Scutellata hybrids (Sanford 2006).

Another example involves the introduction of the Harlequin ladybeetle, Harmonia axyridis, native to East Asia, to other parts of the world as a “natural” form of pest control. Harlequin ladybeetles are natural predators of some of the aphids and other crop-pest insects. First introduced to North America in 1916, the “biocontrol” strains of Harlequin ladybeetles were considered to be quite successful in reducing crop pests and saving farmers substantial amounts of money. After many decades of successful use in North America, biocontrol strains of Harlequin ladybeetles were also developed in Europe and South America in the 1980s.

Over the seven decades of biocontrol use, the Harlequin ladybeetle had never shown any potential for development of wild colonies outside of its native habitat in China and Japan. New generations of beetles always had to be reared in the lab. That all changed in 1988, when a wild colony took root near New Orleans, Louisiana. Either through admixture with a native ladybeetle strain, or due to a spontaneous mutation, a new allele was clearly introduced into this population that suddenly enabled them to survive and reproduce in a wide range of environments. This population spread rapidly across the Americas and had reached Africa by 2004.

In Europe, the invasive, North American strain of Harlequin ladybeetle admixed with the European strain (Figure 4.13), causing a population explosion (Lombaert et al. 2010). Even strains specifically developed to be flightless (to curtail the spreading) produced flighted offspring after admixture with members of the North American population (Facon et al. 2011). The fast-spreading, invasive strain has quickly become a disaster, out-competing native ladybeetle populations (some to the point of extinction), causing home infestations, decimating fruit crops, and contaminating many batches of wine with their bitter flavor after being inadvertently harvested with the grapes (Pickering et al. 2004).

Natural Selection

The final force of evolution is natural selection. This is the evolutionary process that Charles Darwin first brought to light, and it is what the general public typically evokes when considering the process of evolution. Natural selection occurs when certain phenotypes confer an advantage or disadvantage in survival and/or reproductive success. The alleles associated with those phenotypes will change in frequency over time due to this selective pressure. It’s also important to note that the advantageous allele may change over time (with environmental changes) and that an allele that had previously been benign may become advantageous or detrimental. Of course, dominant, recessive, and codominant traits will be selected upon a bit differently from one another. Because natural selection acts on phenotypes rather than the alleles themselves, deleterious (disadvantageous) alleles can be retained by heterozygotes without any negative effects.

In the case of our primordial ocean cells, up until now, the texture of their cell membranes has been benign. The frequencies of smooth to ruffled alleles, and smooth to ruffled phenotypes, has changed over time, due to genetic drift and gene flow. Let’s now imagine that the Earth’s climate has cooled to a point that the waters frequently become too cold for survival of the tiny bacteria that are the dietary staples of our smooth and ruffled cell populations. The way amoeba-like cells “eat” is to stretch out the cell membrane, almost like an arm, to encapsulate, then ingest, the tiny bacteria. When the temperatures plummet, the tiny bacteria populations plummet with them. Larger bacteria, however, are better able to withstand the temperature change.

The smooth cells were well-adapted to ingesting tiny bacteria but poorly suited to encapsulating the larger bacteria. The cells with the ruffled membranes, however, are easily able to extend their ruffles to encapsulate the larger bacteria. They also find themselves able to stretch their entire membrane to a much larger size than their smooth-surfaced neighbors, allowing them to ingest more bacteria at a given time and to go for longer periods between feedings (Figure 4.14).

The smooth and ruffled traits, which had previously offered no advantage or disadvantage while food was plentiful, now are subject to natural selection. During the cold snaps, at least, the ruffled cells have a definite advantage. We can imagine that the western population that has mostly ruffled alleles will continue to do well, while the eastern population is at risk of dying out if the smaller bacteria remain scarce and no ruffled alleles are introduced.

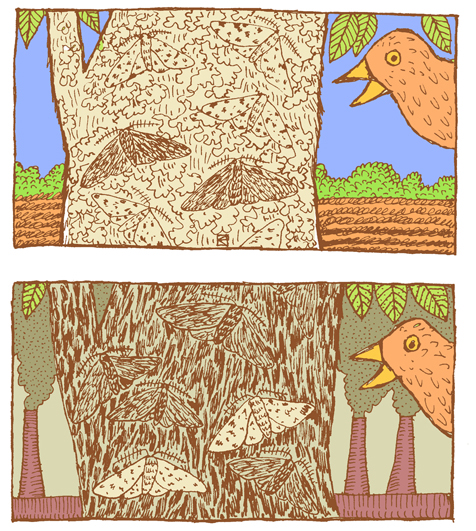

A classic example of natural selection involves the study of an insect called the peppered moth (Biston betularia) in England during the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, the peppered moth population was predominantly light in color, with dark (pepper-like) speckles on the wings. The “peppered” coloration was very similar to the appearance of the bark and lichens that grew on the local trees (Figure 4.15). This helped to camouflage the moths as they rested on a tree, making it harder for moth-eating birds to find and snack on them. There was another phenotype that popped up occasionally in the population. These individuals were heterozygotes that carried an overactive, dominant pigment allele, producing a solid black coloration. As you can imagine, the black moths were much easier for birds to spot, making this phenotype a real disadvantage.

The situation changed, however, as the Industrial Revolution took off. Large factories began spewing vast amounts of coal smoke into the air, blanketing the countryside, including the lichens and trees, in black soot. Suddenly, it was the light-colored moths that were easy for birds to spot and the black moths that held the advantage. The frequency of the dark pigment allele rose dramatically. By 1895, the black moth phenotype accounted for 98% of observed moths (Grant 1999).

Thanks to new environmental regulations in the 1960s, the air pollution in England began to taper off. As the soot levels decreased, returning the trees to their former, lighter color, this provided the perfect opportunity to study how the peppered moth population would respond. Repeated follow-up studies documented the gradual rise in the frequency of the lighter-colored phenotype. By 2003, the maximum frequency of the dark phenotype was 50% and in most parts of England had decreased to less than 10% (Cook 2003).

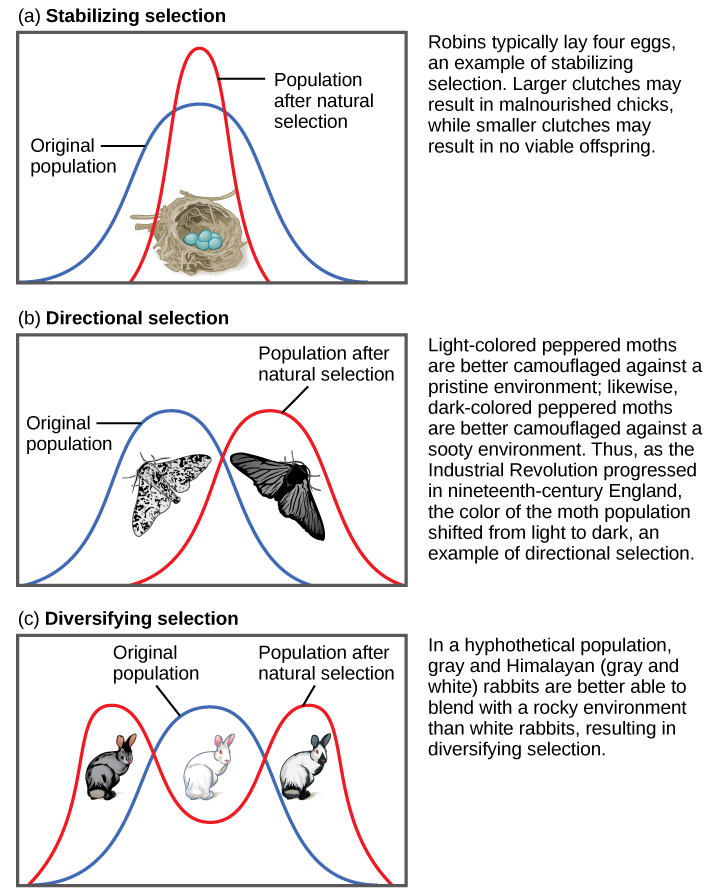

Directional, Balancing/Stabilizing, and Disruptive/Diversifying Selection

Natural selection can be classified as directional, balancing/stabilizing, or disruptive/diversifying, depending on how the pressure is applied to the population (Figure 4.16).

Both of the above examples of natural selection involve directional selection: the environmental pressures favor one phenotype over the other and cause the frequencies of the associated advantageous alleles (ruffled membranes, dark pigment) to gradually increase. In the case of the peppered moths, the direction shifted three times: first, it was selecting for lighter pigment; then, with the increase in pollution, the pressure switched to selection for darker pigment; finally, with reduction of the pollution, the selection pressure shifted back again to favoring light-colored moths.

Balancing selection (a.k.a. stabilizing selection) occurs when selection works against the extremes of a trait and favors the intermediate phenotype. For example, humans maintain an average birth weight that balances the need for babies to be small enough not to cause complications during pregnancy and childbirth but big enough to maintain a safe body temperature after they are born. Another example of balancing selection is found in the genetic disorder called sickle cell anemia (see “Special Topic: Sickle Cell Anemia”).

Disruptive selection (a.k.a. diversifying selection), the opposite of balancing selection, occurs when both extremes of a trait are advantageous. Since individuals with traits in the mid-range are selected against, disruptive selection can eventually lead to the population evolving into two separate species. Darwin believed that the many species of finches (small birds) found in the remote Galapagos Islands provided a clear example of disruptive selection leading to speciation. He observed that seed-eating finches either had large beaks, capable of eating very large seeds, or small beaks, capable of retrieving tiny seeds. The islands did not have many plants that produced medium-size seeds. Thus, birds with medium-size beaks would have trouble eating the very large seeds and would also have been inefficient at picking up the tiny seeds. Over time, Darwin surmised, this pressure against mid-size beaks may have led the population to divide into two separate species.

Sexual Selection

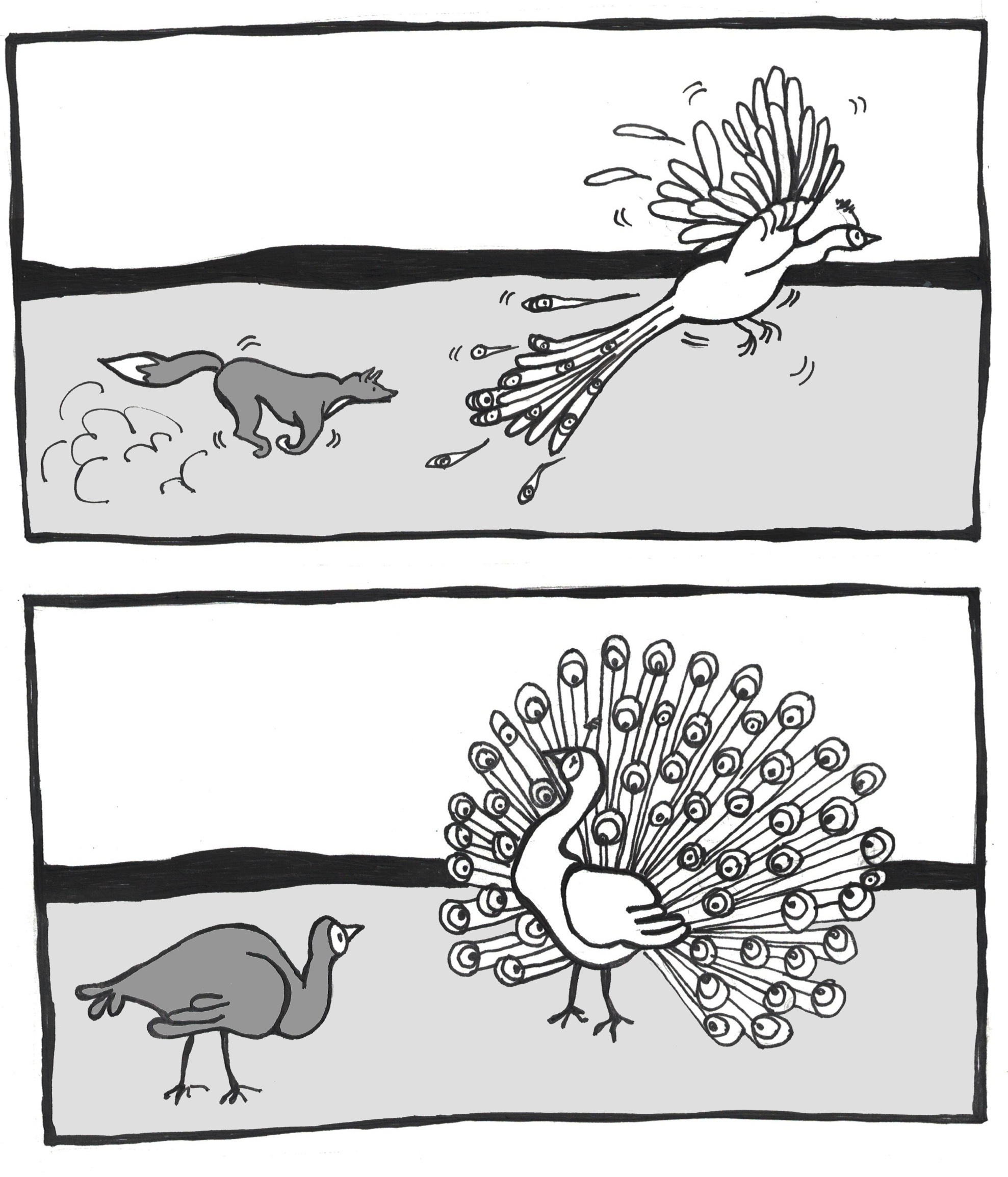

Sexual selection is an aspect of natural selection in which the selective pressure specifically affects reproductive success (the ability to successfully breed and raise offspring) rather than survival. Sexual selection favors traits that will attract a mate. Sometimes these sexually appealing traits even carry greater risks in terms of survival.

A classic example of sexual selection involves the brightly colored feathers of the peacock. The peacock is the male sex of the peafowl genera Pavo and Afropavo. During mating season, peacocks will fan their colorful tails wide and strut in front of the peahens in a grand display. The peahens will carefully observe these displays and will elect to mate with the male that they find the most appealing. Many studies have found that peahens prefer the males with the fullest, most colorful tails. While these large, showy tails provide a reproductive advantage, they can be a real burden in terms of escaping predators. The bright colors and patterns as well as the large size of the peacock tail make it difficult to hide. Once predators spot them, peacocks also struggle to fly away, with the heavy tail trailing behind and weighing them down (Figure 4.17). Some researchers have argued that the increased risk is part of the appeal for the peahens: only an especially strong, alert, and healthy peacock would be able to avoid predators while sporting such a spectacular tail.

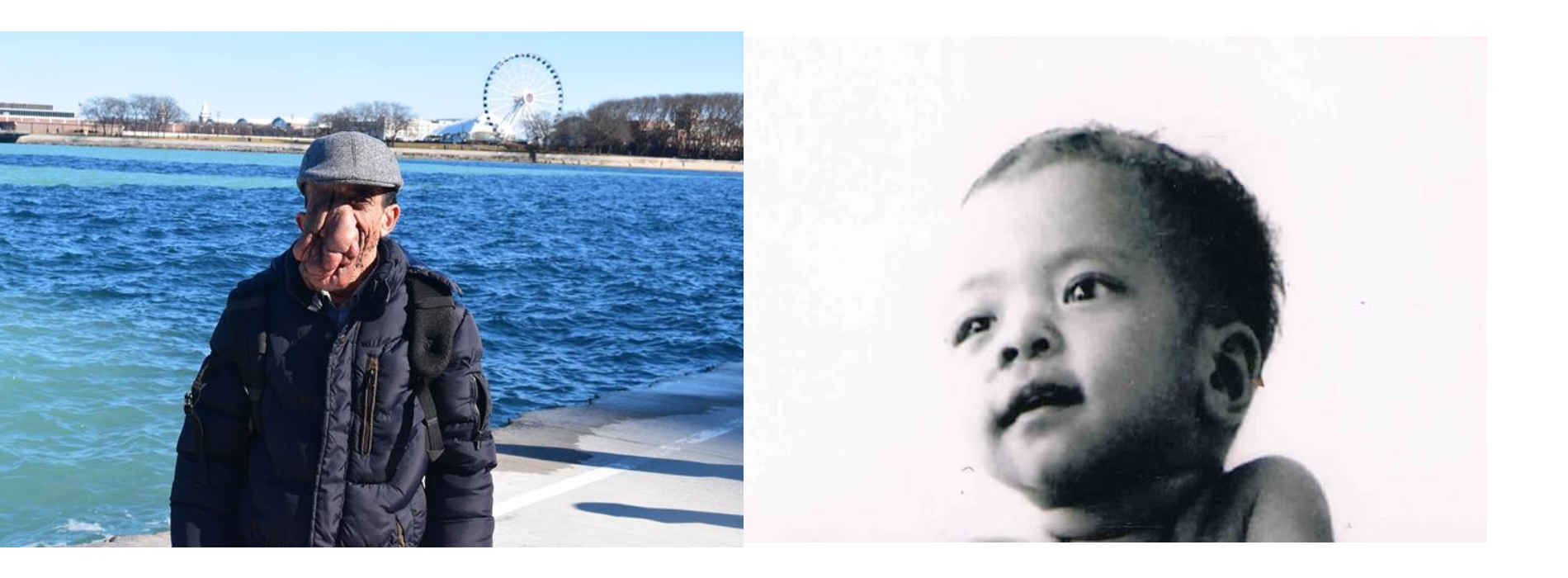

It’s important to keep in mind that sexual selection relies on the trait being present throughout mating years. Reflecting on the NF1 genetic disorder (see “Special Topic: Neurofibromatosis Type 1 [NF1]”), given how disfiguring the symptoms can become, some might find it surprising that half of the babies born with NF1 inherited it from a parent. Given that the disorder is autosomal dominant and fully penetrant (meaning it has no unaffected carriers), it may seem surprising that sexual selection doesn’t exert more pressure against the mutated alleles. One important factor is that, while the neurofibromas typically begin to appear during puberty, they usually emerge only a few at a time and may grow very slowly. Many NF1 patients don’t experience the more severe or disfiguring symptoms until later in life, long after they have started families of their own.

Some researchers prefer to classify sexual selection separately, as a fifth force of evolution. The traits that underpin mate selection are entirely natural, of course. Research has shown that subtle traits, such as the type of pheromones (hormonal odors related to immune system alleles) someone emits and how those are perceived by the immune system genotype of the “sniffer,” may play crucial and subconscious roles in whether we find someone attractive or not (Chaix, Cao, and Donnelly 2008).

Special Topic: Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1)

Neurofibromatosis Type 1, also known as NF1, is a genetic disorder that illustrates how a mutation in a single gene can affect multiple systems in the body. Surprisingly common, more people have NF1 than cystic fibrosis and muscular dystrophy combined. Even more surprising, given how common it is, is how few people have heard of it. One in every 3,000 babies is born with NF1, and this holds true for all populations worldwide (Riccardi 1992). This means that, for every 3,000 people in your community, there is likely at least one person living with this disorder. NF1 is an autosomal dominant condition, which means that everyone born with a mutation in the gene, whether inherited or spontaneous, has a 50/50 chance of passing it on to each of their own children.

The NF1 disorder results from mutation of the NF1 gene on Chromosome 17. Almost any mutation that affects the sequence of the gene’s protein product, neurofibromin, will cause the disorder. Studies of individuals with NF1 have identified over 3,000 different mutations of all kinds (including point mutations, small and large indels, and translocations). The NF1 gene is one of the largest known genes, containing at least 60 exons (protein-encoding sequences) in a span of about 300,000 nucleotides.

We know that neurofibromin plays an important role in preventing tumor growth because one of the most common symptoms of the NF1 disorder is the growth of benign (noncancerous) tumors, called neurofibromas. Neurofibromas sprout from nerve sheaths—the tissues that encase our nerves—throughout the body, usually beginning around puberty. There is no way to predict where the tumors will occur, or when or how quickly they will grow, although only about 15% turn malignant (cancerous). The two types of neurofibromas that are typically most visible are cutaneous neurofibromas, which are spherical bumps on, or just under, the surface of the skin (Figure 4.18), and plexiform neurofibromas, growths involving whole branches of nerves, often giving the appearance that the surface of the skin is “melting” (Figure 4.19).

Unfortunately, there is currently no cure for NF1. Surgical removal of neurofibromas risks paralysis, due to the high potential for nerve damage, and often results in the tumors growing back even more vigorously. This means that patients are often forced to live with disfiguring and often painful neurofibromas. People who are not familiar with NF1 often mistake neurofibromas for something contagious. This makes it especially hard for people living with NF1 to get jobs working with the public or even to enjoy spending time away from home. Raising public awareness about NF1 and its symptoms can be a great help in improving the quality of life for people living with this condition.

One of the first symptoms of NF1 in a small child is usually the appearance of café-au-lait spots, or CALS, which are flat, brown birthmark-like spots on the skin (Figure 4.20). CALS are often light brown, similar to the color of coffee with cream, which is the reason for the name, although the shade of the pigment depends on a person’s overall complexion. Some babies are born with CALS, but for others the spots appear within the first few years of life. Having six or more CALS larger than five millimeters (mm) across is a strong indicator that a child may have NF1.

Other common symptoms include the following: gliomas (tumors) of the optic nerve, which can cause vision loss; thinning of bones and failure to heal if they break (often requiring amputation); low muscle tone (poor muscle development, often delaying milestones such as sitting up, crawling, and walking); hearing loss, due to neurofibromas on auditory nerves; and learning disabilities, especially those involving spatial reasoning. Approximately 50% of people with NF1 have some type of speech and/or learning disability and often benefit greatly from early intervention services. Generalized developmental disability, however, is not common with NF1, so most people with NF1 live independently as adults. Many people with NF1 live full and successful lives, as long as their symptoms can be managed.

Based on the wide variety of symptoms, it’s clear that the neurofibromin protein plays important roles in many biochemical pathways. While everyone who has NF1 will exhibit some symptoms during their lifetime, there is a great deal of variation in the types and severity of symptoms, even between individuals from the same family who share the exact same NF1 mutation. It seems crazy that a gene with so many important functions would be so susceptible to mutation. Part of this undoubtedly has to do with its massive size—a gene with 300,000 nucleotides has ten times more nucleotides available for mutation than does a gene of 30,000 bases. This also suggests that the mutability of this gene might provide some benefits, which is a possibility that we will revisit later in this chapter.

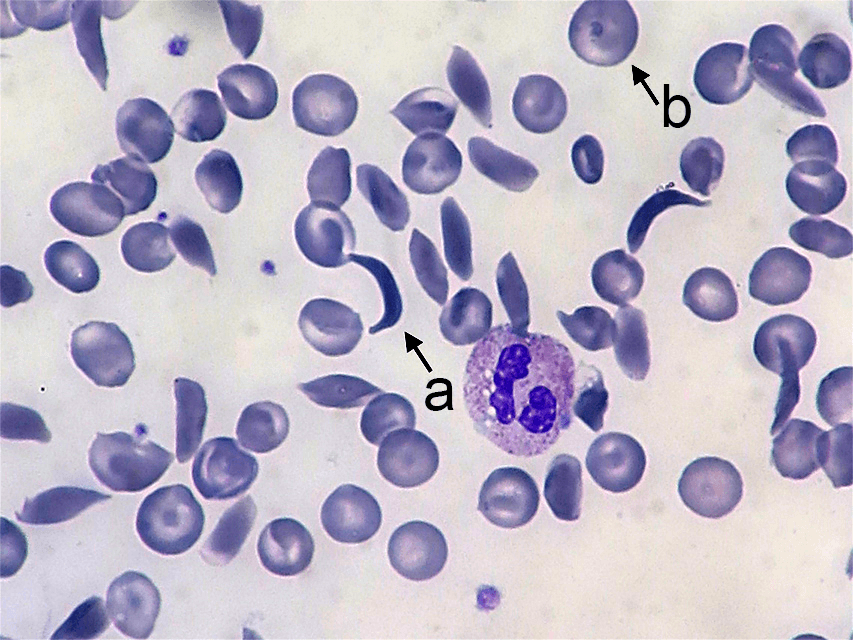

Special Topic: Sickle Cell Anemia

Sickle cell anemia is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder that affects millions of people worldwide. It is most common in Africa, countries around the Mediterranean Sea, and eastward as far as India. Populations in the Americas that have high percentages of ancestors from these regions also have high rates of sickle cell anemia. In the United States, it’s estimated that 72,000 people live with the disease, with one in approximately 1,200 Hispanic-American babies and one in every 500 African-American babies inheriting the condition (World Health Organization 1996).

Sickle cell anemia affects the hemoglobin protein in red blood cells. Normal red blood cells are somewhat doughnut-shaped—round with a depression on both sides of the middle. They carry oxygen around the bloodstream to cells throughout the body. Red blood cells produced by the mutated form of the gene take on a stiff, sickle-like crescent shape when stressed by low oxygen or dehydration (Figure 4.21). Because of their elongated shape and the fact that they are stiff rather than flexible, they tend to form clumps in the blood vessels, inhibiting blood flow to adjacent areas of the body. This causes episodes of extreme pain and can cause serious problems in the oxygen-deprived tissues. The sickle cells also break down much more quickly than normal cells, often lasting only 20 days rather than the 120 days of normal cells. This causes an overall shortage of blood cells in the sickle cell patient, resulting in low iron (anemia) and problems associated with it such as extreme fatigue, shortness of breath, and hindrances to children’s growth and development.

The devastating effects of sickle cell anemia made its high frequency a pressing mystery. Why would an allele that is so deleterious in its homozygous form be maintained in a population at levels as high as the one in twelve African Americans estimated to carry at least one copy of the allele? The answer turned out to be one of the most interesting cases of balancing selection in the history of genetic study.

While looking for an explanation, scientists noticed that the countries with high rates of sickle cell disease also shared a high risk for another disease called malaria, which is caused by infection of the blood by a Plasmodium parasite. These parasites are carried by mosquitoes and enter the human bloodstream via a mosquito bite. Once infected, the person will experience flu-like symptoms that, if untreated, can often lead to death. Researchers discovered that many people living in these regions seemed to have a natural resistance to malaria. Further study revealed that people who carry the sickle cell allele are far less likely to experience a severe case of malaria. This would not be enough of a benefit to make the allele advantageous for the sickle cell homozygotes, who face shortened life spans due to sickle cell anemia. The real benefit of the sickle cell allele goes to the heterozygotes.

People who are heterozygous for sickle cell carry one normal allele, which produces the normal, round, red blood cells, and one sickle cell allele, which produces the sickle-shaped red blood cells. Thus, they have both the sickle and round blood cell types in their bloodstream. They produce enough of the round red blood cells to avoid the symptoms of sickle cell anemia, but they have enough sickle cells to provide protection from malaria.

When the Plasmodium parasites infect an individual, they begin to multiply in the liver, but then must infect the red blood cells to complete their reproductive cycle. When the parasites enter sickle-type cells, the cells respond by taking on the sickle shape. This prevents the parasite from circulating through the bloodstream and completing its life cycle, greatly inhibiting the severity of the infection in the sickle cell heterozygotes compared to non–-sickle cell homozygotes. See Chapter 14 for more discussion of sickle cell anemia.

Special Topic: The Real Primordial Cells—Dictyostelium Discoideum

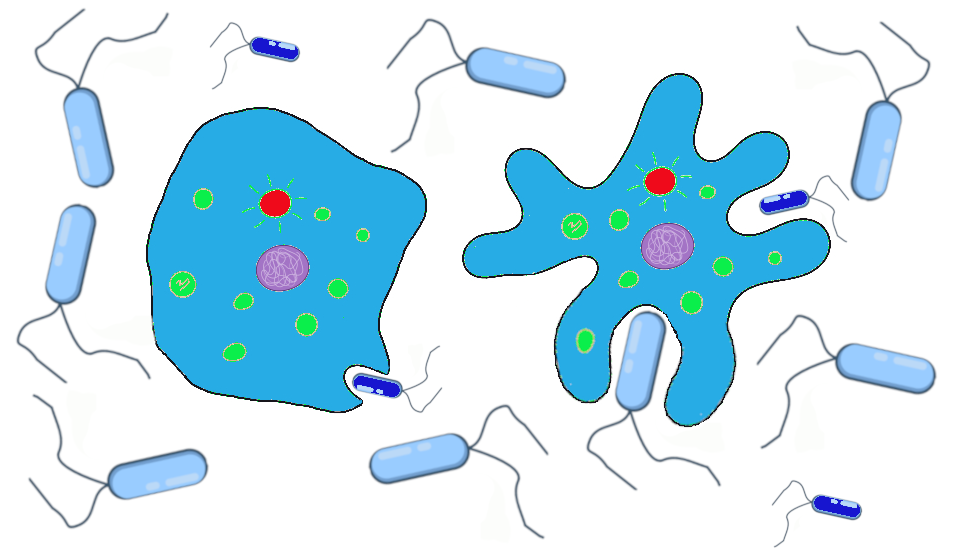

The amoeba-like primordial cells that were used as recurring examples throughout this chapter are inspired by actual research that is truly fascinating. In 2015, Gareth Bloomfield and colleagues reported on their genomic study of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum (a.k.a. “slime molds,” although technically they are amoebae, not molds). Strains of these amoebae have been grown in research laboratories for many decades and are useful in studying the mechanisms that amoeboid single-celled organisms use to ingest food and liquid. For simplification of our examples in this chapter, our amoeba-like cells remained ocean dwellers. Wild Dictyostelium discoideum, however, live in soil and feed on soil bacteria by growing ruffles in their membranes that reach out to encapsulate the bacterial cell. Laboratory strains, however, are typically raised on liquid media (agar) in Petri dishes, which is not suitable for the wild-type amoebae. It was widely known that the laboratory strains must have developed mutations in one or more genes to allow them to ingest the larger nutrient particles in the agar and larger volumes of liquid, but the genes involved were not known.

Bloomfield and colleagues performed genomic testing on both the wild and the laboratory strains of Dictyostelium discoideum. Their discovery was astounding: every one of the laboratory strains carried a mutation in the NF1 gene, the very same gene associated with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) in humans. The antiquity of this massive, easily mutated gene is incredible. It originated in an ancestor common to both humans and these amoebae, and it has been retained in both lineages ever since. As seen in Dictyostelium discoideum, breaking the gene can be advantageous. Without a functioning copy of the neurofibromin protein, the cell membrane is able to form much-larger feeding structures, allowing the NF1 mutants to ingest larger particles and larger volumes of liquid. For these amoebae, this may provide dietary flexibility that functions somewhat like an insurance policy for times when the food supply is limited.

Dictyostelium discoideum are also interesting in that they typically reproduce asexually, but under certain conditions, one cell will convert into a “giant” cell, which encapsulates surrounding cells, transforming into one of three sexes. This cell will undergo meiosis, producing gametes that must combine with one of the other two sexes to produce viable offspring. This ability for sexual reproduction may be what allows Dictyostelium discoideum to benefit from the advantages of NF1 mutation, while also being able to restore the wild type NF1 gene in future generations.

What does this mean for humans living with NF1? Well, understanding the role of the neurofibromin protein in the membranes of simple organisms like Dictyostelium discoideum may help us to better understand how it functions and malfunctions in the sheaths of human neurons. It’s also possible that the mutability of the NF1 gene confers certain advantages to humans as well. Alleles of the NF1 gene have been found to reduce one’s risk for alcoholism (Repunte-Canonigo Vez et al. 2015), opiate addiction (Sanna et al. 2002), Type 2 diabetes (Martins et al. 2016), and hypomusicality (a lower-than-average musical aptitude; Cota et al. 2018). This research is ongoing and will be exciting to follow in the coming years.

Studying Evolution in Action

The Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

This chapter has introduced you to the forces of evolution, the mechanisms by which evolution occurs. How do we detect and study evolution, though, in real time, as it happens? One tool we use is the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium: a mathematical formula that allows estimation of the number and distribution of dominant and recessive alleles in a population. This aids in determining whether allele frequencies are changing and, if so, how quickly over time, and in favor of which allele? It’s important to note that the Hardy-Weinberg formula only gives us an estimate based on the data for a snapshot in time. We will have to calculate it again later, after various intervals, to determine if our population is evolving and in what way the allele frequencies are changing. To learn how to calculate the Hardy-Weinberg formula, see “Special Topic: Calculating the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium” at the end of the chapter.

Special Topic: Calculating the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (include here but not as special topic just normal paragraph)

Interpreting Evolutionary Change: Nonrandom Mating

Once we have detected change occurring in a population, we need to consider which evolutionary processes might be the cause of the change. It is important to watch for nonrandom mating patterns, to see if they can be included or excluded as possible sources of variation in allele frequencies.

Nonrandom mating (also known as assortative mating) occurs when mate choice within a population follows a nonrandom pattern.

Positive assortative mating patterns result from a tendency for individuals to mate with others who share similar phenotypes. This often happens based on body size. Taking as an example dog breeds, it is easier for two Chihuahuas to mate and have healthy offspring than it is for a Chihuahua and a St. Bernard to do so. This is especially true if the Chihuahua is the female and would have to give birth to giant St. Bernard pups.

Negative assortative mating patterns occur when individuals tend to select mates with qualities different from their own. This is what is at work when humans choose partners whose pheromones indicate that they have different and complementary immune alleles, providing potential offspring with a better chance at a stronger immune system.

Among domestic animals, such as pets and livestock, assortative mating is often directed by humans who decide which pairs will mate to increase the chances of offspring having certain desirable traits. This is known as artificial selection.

Among humans, in addition to phenotypic traits, cultural traits such as religion and ethnicity may also influence assortative mating patterns.

Defining a Species

Species are organisms whose individuals are capable of breeding because they are biologically and behaviorally compatible to produce viable, fertile offspring. Viable offspring are those offspring that are healthy enough to survive to adulthood. Fertile offspring are able to reproduce successfully, resulting in offspring of their own. Both conditions must be met for individuals to be considered part of the same species. As you can imagine, these criteria complicate the identification of distinct species in fossilized remains of extinct populations. In those cases, we must examine how much phenotypic variation is typically found within a comparable modern-day species; we can then determine whether the fossilized remains fall within the expected range of variation for a single species.

Some species have subpopulations that are regionally distinct. These are classified as separate subspecies because they have their own unique phenotypes and are geographically isolated from one another. However, if they do happen to encounter one another, they are still capable of successful interbreeding.

There are many examples of sterile hybrids that are offspring of parents from two different species. For example, horses and donkeys can breed and have offspring together. Depending on which species is the mother and which is the father, the offspring are either called mules, or hennies. Mules and hennies can live full life spans but are not able to have offspring of their own. Likewise, tigers and lions have been known to mate and have viable offspring. Again, depending on which species is the mother and which is the father, these offspring are called either ligers or tigons. Like mules and hennies, ligers and tigons are unable to reproduce. In each of these cases, the mismatched set of chromosomes that the offspring inherit produce an adequate set of functioning genes for the hybrid offspring; however, once mixed and divided in meiosis, the gametes don’t contain the full complement of genes needed for survival in the third generation.

Micro- to Macroevolution

Microevolution refers to changes in allele frequencies within breeding populations—that is, within single species. Macroevolution describes how the similarities and differences between species, as well as the phylogenetic relationships with other taxa, lead to changes that result in the emergence of new species. Consider our example of the peppered moth that illustrated microevolution over time, via directional selection favoring the peppered allele when the trees were clean and the dark pigment allele when the trees were sooty. Imagine that environmental regulations had cleaned up the air pollution in one part of the nation, while the coal-fired factories continued to spew soot in another area. If this went on long enough, it’s possible that two distinct moth populations would eventually emerge—one containing only the peppered allele and the other only harboring the dark pigment allele.

When a single population divides into two or more separate species, it is called speciation. The changes that prevent successful breeding between individuals who descended from the same ancestral population may involve chromosomal rearrangements, changes in the ability of the sperm from one species to permeate the egg membrane of the other species, or dramatic changes in hormonal schedules or mating behaviors that prevent members from the new species from being able to effectively pair up.

There are two types of speciation: allopatric and sympatric. Allopatric speciation is caused by long-term isolation (physical separation) of subgroups of the population (Figure 4.22). Something occurs in the environment—perhaps a river changes its course and splits the group, preventing them from breeding with members on the opposite riverbank. Over many generations, new mutations and adaptations to the different environments on each side of the river may drive the two subpopulations to change so much that they can no longer produce fertile, viable offspring, even if the barrier is someday removed.

Sympatric speciation occurs when the population splits into two or more separate species while remaining located together without a physical barrier. This typically results from a new mutation that pops up among some members of the population that prevents them from successfully reproducing with anyone who does not carry the same mutation. This is seen particularly often in plants, as they have a higher frequency of chromosomal duplications.

One of the quickest rates of speciation is observed in the case of adaptive radiation. Adaptive radiation refers to the situation in which subgroups of a single species rapidly diversify and adapt to fill a variety of ecological niches. An ecological niche is a set of constraints and resources that is available in an environmental setting. Evidence for adaptive radiations is often seen after population bottlenecks. A mass disaster kills off many species, and the survivors have access to a new set of territories and resources that were either unavailable or much coveted and fought over before the disaster. The offspring of the surviving population will often split into multiple species, each of which stems from members in that first group of survivors who happened to carry alleles that were advantageous for a particular niche.

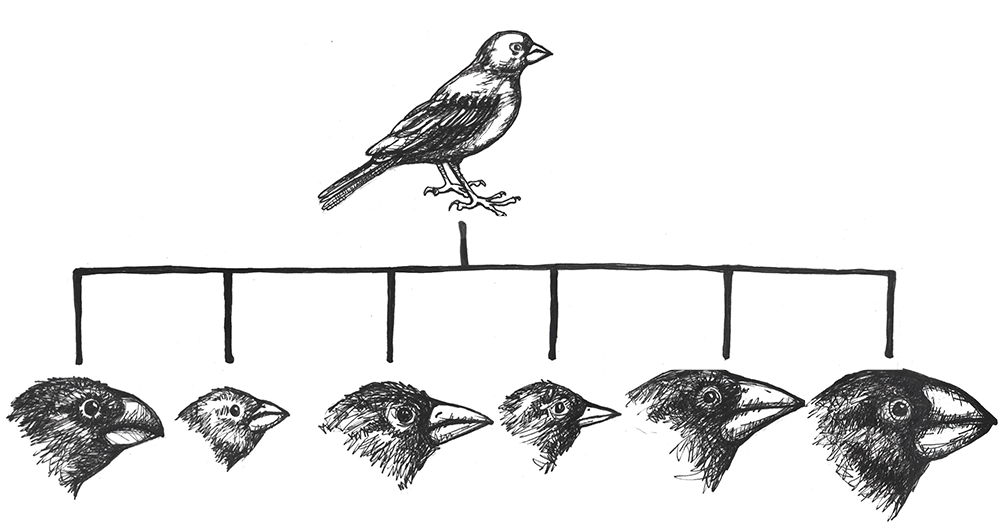

The classic example of adaptive radiation brings us back to Charles Darwin and his observations of the many species of finches on the Galapagos Islands. We are still not sure how the ancestral population of finches first arrived on that remote Pacific Island chain, but they found themselves in an environment filled with various insects, large and tiny seeds, fruit, and delicious varieties of cactus. Some members of that initial population carried alleles that gave them advantages for each of these dietary niches. In subsequent generations, others developed new mutations, some of which were beneficial. These traits were selected for, making the advantageous alleles more common among their offspring. As the finches spread from one island to the next, they would be far more likely to find mates among the birds on their new island. Birds feeding in the same area were then more likely to mate together than birds who have different diets, contributing to additional assortative mating. Together, these evolutionary mechanisms caused rapid speciation that allowed the new species to make the most of the various dietary niches (Figure 4.23).

In today’s modern world, understanding these evolutionary processes is crucial for developing immunizations and antibiotics that can keep up with the rapid mutation rate of viruses and bacteria. This is also relevant to our food supply, which relies, in large part, on the development of herbicides and pesticides that keep up with the mutation rates of pests and weeds. Viruses, bacteria, agricultural pests, and weeds have all shown great flexibility in developing alleles that make them resistant to the latest medical treatment, pesticide, or herbicide. Billion-dollar industries have specialized in trying to keep our species one step ahead of the next mutation in the pests and infectious diseases that put our survival at risk.

Special Topic: Calculating the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

In the Hardy-Weinberg formula, p represents the frequency of the dominant allele, and q represents the frequency of the recessive allele. Remember, an allele’s frequency is the proportion, or percentage, of that allele in the population. For the purposes of Hardy-Weinberg, we give the allele percentages as decimal numbers (e.g., 42% = 0.42), with the entire population (100% of alleles) equaling 1. If we can figure out the frequency of one of the alleles in the population, then it is simple to calculate the other. Simply subtract the known frequency from 1 (the entire population): 1 – p = q and 1 – q = p.

The Hardy-Weinberg formula is p2 + 2pq + q2, where:

p2 represents the frequency of the homozygous dominant genotype;

2pq represents the frequency of the heterozygous genotype; and

q2 represents the frequency of the homozygous recessive genotype.

It is often easiest to determine q2 first, simply by counting the number of individuals with the unique, homozygous recessive phenotype (then dividing by the total individuals in the population to arrive at the “frequency”). Once we have this number, we simply need to calculate the square root of the homozygous recessive phenotype frequency. That gives us q. Remember, 1 – q equals p, so now we have the frequencies for both alleles in the population. If we needed to figure out the frequencies of heterozygotes and homozygous dominant genotypes, we’d just need to plug the p and q frequencies back into the p2 and 2pq formulas.

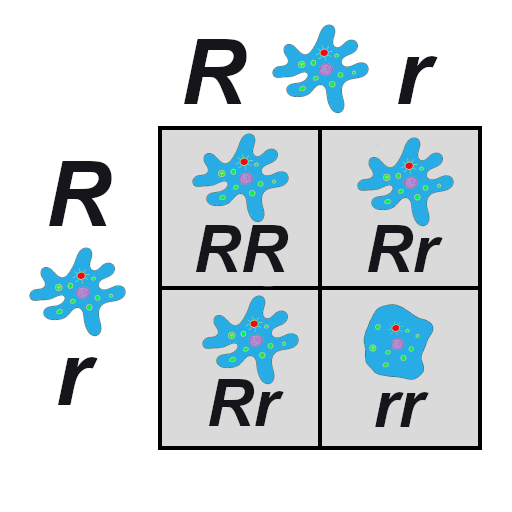

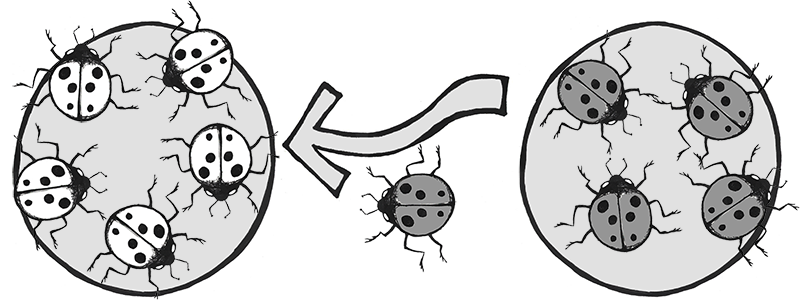

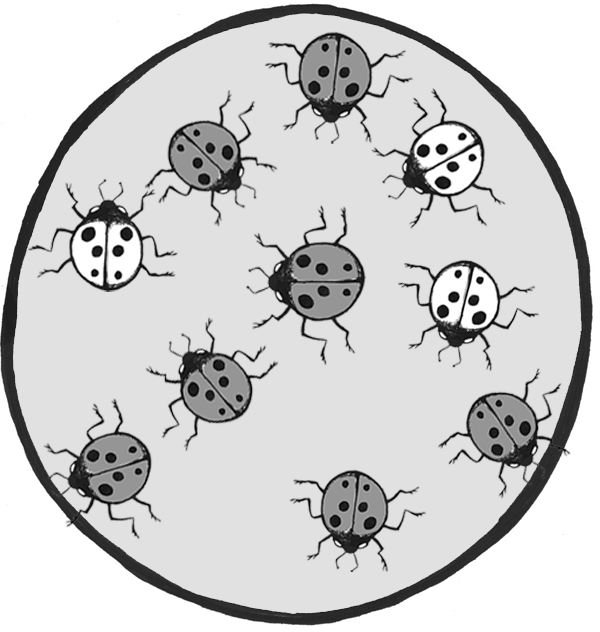

Let’s imagine we have a population of ladybeetles that carries two alleles: a dominant allele that produces red ladybeetles and a recessive allele that produces orange ladybeetles. Since red is dominant, we’ll use R to represent the red allele, and r to represent the orange allele. Our population has ten beetles, and seven are red and three are orange (Figure 4.24). Let’s calculate the number of genotypes and alleles in this population.

Of ten total beetles, we have three orange beetles3/10 = .30 (30%) frequency—and we know they are homozygous recessive (rr). So:

rr = .3; therefore, r = √.3 = .5477

R = 1 – .5477 = .4523

Using the Hardy-Weinberg formula:

1=.45232 + 2 x .4523 x .5477 +.54772 = .20 + .50 + .30 = 1

Thus, the genotype breakdown is 20% RR, 50% Rr, and 30% rr

(2 red homozygotes, 5 red heterozygotes, and 3 orange homozygotes).

Since we have 10 individuals, we know we have 20 total alleles: 4 red from the RR group, 5 red and 5 orange from the Rr group, and 6 orange from the rr group, for a grand total of 9 red and 11 orange (45% red and 55% orange, just like we estimated in the 1 – q step).

Reminder: The Hardy-Weinberg formula only gives us an estimate for a snapshot in time. We will have to calculate it again later, after various intervals, to determine if our population is evolving and in what way the allele frequencies are changing.

Review Questions

- Summarize the Modern Synthesis and provide several examples of how it is relevant to questions and problems in our world today.

- You inherit a house from a long-lost relative that contains a fancy aquarium, filled with a variety of snails. The phenotypes include large snails and small snails; red, black, and yellow snails; and solid, striped, and spotted snails. Devise a series of experiments that would help you determine how many snail species are present in your aquarium.

- Match the correct force of evolution with the correct real-world example:

a. Mutationi. 5-alpha reductase deficiency

b. Genetic Driftii. Peppered Moths

c. Gene Flowiii. Neurofibromatosis Type 1

d. Natural Selectioniv. Scutellata Honey Bees - Imagine a population of common house mice (Mus musculus). Draw a comic strip illustrating how mutation, genetic drift, gene flow, and natural selection might transform this population over several (or more) generations.

-

The many breeds of the single species of domestic dog (Canis familiaris) provide an extreme example of microevolution. Discuss why this is the case. What future scenarios can you imagine that could potentially transform the domestic dog into an example of macroevolution?

-

The ability to roll one’s tongue (lift the outer edges of the tongue to touch each other, forming a tube) is a dominant trait. In a small town of 1,500 people, 500 can roll their tongues. Use the Hardy-Weinberg formula to determine how many individuals in the town are homozygous dominant, heterozygous, and homozygous recessive.

Key Terms

5-alpha reductase deficiency: An autosomal recessive syndrome that manifests when a child having both X and Y sex chromosomes inherits two nonfunctional (mutated) copies of the SRD5A2 gene, producing a deficiency in a hormone necessary for development in infancy of typical male genitalia. These children often appear at birth to have female genitalia, but they develop a penis and other sexual characteristics when other hormones kick in during puberty.

Adaptive radiation: The situation in which subgroups of a single species rapidly diversify and adapt to fill a variety of ecological niches.

Admixture: A term often used to describe gene flow between human populations. Sometimes also used to describe gene flow between nonhuman populations.

Allele frequency: The ratio, or percentage, of one allele compared to the other alleles for that gene within the study population.

Alleles: Variant forms of genes.

Allopatric speciation: Speciation caused by long-term isolation (physical separation) of subgroups of the population.

Antibiotics: Medicines prescribed to treat bacterial infections.

Artificial selection: Human-directed assortative mating among domestic animals, such as pets and livestock, designed to increase the chances of offspring having certain desirable traits.

Asexual reproduction: Reproduction via mitosis, whereby offspring are clones of the parents.

Autosomal dominant: A phenotype produced by a gene on an autosomal chromosome that is expressed, to the exclusion of the recessive phenotype, in heterozygotes.

Autosomal recessive: A phenotype produced by a gene on an autosomal chromosome that is expressed only in individuals homozygous for the recessive allele.

Balanced translocations: Chromosomal translocations in which the genes are swapped but no genetic information is lost.

Balancing selection: A pattern of natural selection that occurs when the extremes of a trait are selected against, favoring the intermediate phenotype (a.k.a. stabilizing selection).

Beneficial mutations: Mutations that produce some sort of an advantage to the individual.

Benign: Noncancerous. Benign tumors may cause problems due to the area in which they are located (e.g., they might put pressure on a nerve or brain area), but they will not release cells that aggressively spread to other areas of the body.

Café-au-lait spots (CALS): Flat, brown birthmark-like spots on the skin, commonly associated with Neurofibromatosis Type 1.

Chromosomal translocations: The transfer of DNA between nonhomologous chromosomes.

Chromosomes: Molecules that carry collections of genes.

Codons: Three-nucleotide units of DNA that function as three-letter “words,” encoding instructions for the addition of one amino acid to a protein or indicating that the protein is complete.

Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction: A mass disaster caused by an asteroid that struck the earth approximately 66 million years ago and killed 75% of life on Earth, including all terrestrial dinosaurs. (a.k.a. K-Pg Extinction, Cretatious-Tertiary Extinction, and K-T Extinction).

Crossover events: Chromosomal alterations that occur when DNA is swapped between homologous chromosomes while they are paired up during meiosis I.

Cutaneous neurofibromas: Neurofibromas that manifest as spherical bumps on or just under the surface of the skin.

Deleterious mutation: A mutation producing negative effects to the individual such as the beginnings of cancers or heritable disorders.

Deletions: Mutations that involve the removal of one or more nucleotides from a DNA sequence.

Derivative chromosomes: New chromosomal structures resulting from translocations.

Dictyostelium discoideum: A species of social amoebae that has been widely used for laboratory research. Laboratory strains of Dictyostelium discoideum all carry mutations in the NF1 gene, which is what allows them to survive on liquid media (agar) in Petri dishes.

Directional selection: A pattern of natural selection in which one phenotype is favored over the other, causing the frequencies of the associated advantageous alleles to gradually increase.

Disruptive selection: A pattern of natural selection that occurs when both extremes of a trait are advantageous and intermediate phenotypes are selected against (a.k.a. diversifying selection).

DNA repair mechanisms: Enzymes that patrol and repair DNA in living cells.

DNA transposons: Transposons that are clipped out of the DNA sequence itself and inserted elsewhere in the genome.

Ecological niche: A set of constraints and resources that are available in an environmental setting.

Ellis-van Creveld syndrome: An autosomal recessive disorder characterized by short stature (dwarfism), polydactyly (the development of more than five digits [fingers or toes] on the hands or feet), abnormal tooth development, and heart defects. Estimated to affect approximately one in 60,000 individuals worldwide, among the Old Order Amish of Lancaster County, the rate is estimated to be as high as one in every 200 births.

Evolution: A change in the allele frequencies in a population over time.

Exons: The DNA sequences within a gene that directly encode protein sequences. After being transcribed into messenger RNA, the introns (DNA sequences within a gene that do not directly encode protein sequences) are clipped out, and the exons are pasted together prior to translation.

Fertile offspring: Offspring that can successfully reproduce, resulting in offspring of their own.

Founder effect: A type of genetic drift that occurs when members of a population leave the main or “parent” group and form a new population that no longer interbreeds with the other members of the original group.

Frameshift mutations: Types of indels that involve the insertion or deletion of any number of nucleotides that is not a multiple of three. These “shift the reading frame” and cause all codons beyond the mutation to be misread.

Gametes: The reproductive cells, produced through meiosis (a.k.a. germ cells or sperm or egg cells).

Gene: A sequence of DNA that provides coding information for the construction of proteins.

Gene flow: The movement of alleles from one population to another. This is one of the forces of evolution.

Gene pool: The entire collection of genetic material in a breeding community that can be passed on from one generation to the next.

Genetic drift: Random changes in allele frequencies within a population from one generation to the next. This is one of the forces of evolution.

Genotype: The set of alleles that an individual has for a given gene.

Genotype frequencies: The ratios or percentages of the different homozygous and heterozygous genotypes in the population.

Guevedoces: The term coined locally in the Dominican Republic for the condition scientifically known as 5-alpha reductase deficiency. The literal translation is “penis at twelve.”

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium: A mathematical formula (1=p2 + 2pq + q2 ) that allows estimation of the number and distribution of dominant and recessive alleles in a population.